Psalm 21

Victories you give (21:1). Psalm 21 has been compared with a type of prophetic speech widespread in the ancient Near East and called an “oracle of victory.”114 In the face of impending battle, a spokesperson for the king’s god or goddess would offer encouragement to the king. In Syria, a monument of Zakkur, the king of Hamath (ca. 800 B.C.), describes how an oracle strengthened him in the face of a terrifying attack against his city.115 Other examples are common especially in prophetic speech of Assyrian prophets (see Ps. 110).116 In Psalm 21, the words of an oracle of victory might be preserved in verses 8–12. Perhaps a prophetic psalm, like Psalm 21, would have been the source of confidence reflected in a prayer such as in 20:6.

Zakkur Stele

Rama/Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of the Louvre

Fiery furnace (21:9). The Hebrew word translated “furnace” (tannûr) refers to a cooking oven (Ex. 8:3; Lev. 2:4; 7:9). It was constructed of earth, brick, and broken pottery in the shape of a bell, the top of which was open for the chimney. Fire was kindled inside the oven, distributing heat to the inside surface, where the bread dough was placed for cooking.117 Oven heat, being more intense than an ordinary open flame (reducing fuel to hot charcoal), served as a metaphor for destructive power (Hos. 7:7; Mal. 4:1). Such punishment was also known to be literal. A Mesopotamian royal letter from about 600 B.C. instructs a governor to throw corrupt priests into a burning oven (cf. also Dan. 3).118 Such a custom undergirds the rhetorical power of the image in this psalm.

Psalm 22

You are enthroned (22:3). See comments on 99:1.

Womb (22:9–10). See comments on 139:13.

Bulls (22:12). The ancients considered the bull as one of the strongest and most potentially dangerous land animals.119 This is illustrated as early as ca. 3000 B.C. by a slate palette from Egypt depicting a man being gored and trampled by a horned bull.120 Bashan was the high plateau region east of the Sea of Galilee, which was well known as a fertile grassland and therefore conducive to the growth of cattle (Amos 4:1).

The Hunters’ Palette which shows the hunting of two lions and other wild animals. Lions and bulls were often used to represent kings, nations, or oppressors.

Werner Forman Archive/The British Museum

Lions (22:13). While lions no longer inhabit what was the land of ancient Israel, in ancient times they were not uncommon and the danger they posed was well known (1 Sam. 17:34–37; Amos 3:4; 5:19). In addition to their strength and speed, lions used stealth to hunt their victims and were feared both for their teeth and claws. These attributes are illustrated in ancient Near Eastern artwork.121 In Assyrian royal hunts and art, animals (especially lions) symbolized both human enemies and the forces of chaos that the king ritually subdues.122 In this psalm, the reversal of this imagery portrays the afflictions of the psalmist.

Bones are out of joint (22:14). Strain and trauma can result in the sensation of aching joints; however, such language is a common figure of speech for suffering in psalms as well as Mesopotamian laments, even describing the effects of emotional distress (cf. 42:10; see comment on 38:3).123 A Mesopotamian lament used similar imagery in the context of a physical illness: “From writhing, my joints were separated, my limbs were splayed and thrust apart.”124

Potsherd (22:15). When ceramic vessels either broke or became unusable, their fragments, called “potsherds,” were used for writing, for scraping, or as fill. As fired clay, such pieces of used ceramic were extremely dry.

Dogs (22:16). See comments on 59:6, 14–15.

Count all my bones (22:17). In the same Mesopotamian lament cited in v. 14, one finds a description of gauntness. The background to this psalm may be starvation (or even fasting; 109:24) rather than disease as in the Mesopotamian text, or the imagery may be stereotypical for extreme distress: “My bones are loose, covered (only) with skin” (cf. 102:5).125

Not hidden his face (22:24). See comments on 13:1; 42:2.

Fulfill my vows (22:25). See comment on 56:12.

The poor will eat (22:26). The type of offering sacrificed in fulfillment of a vow was a peace offering, which was communal in nature (Lev. 3:1–17; 7:11–21; 1 Sam. 11:15). Choice portions went to Yahweh and were burned on the altar, but the bulk of the animal was shared with other worshipers in the congregation at the temple.

A ritual text from Ugarit (ca. 1300 B.C.) specifies a daily offering of this type: “At that time the king is to sacrifice … a ram for ʾIlu-Beti as a peace offering [Ugar. šlmm = Heb. šelāmîm, Lev. 3:1], all may eat of it.”126 What this type of offering meant for Israelites is that even the poor who came to worship could have something to eat. They ate with the knowledge that God had answered the prayer of the one fulfilling the vow, bringing praise to God.

Who cannot keep themselves alive (22:29). See comments on 49:7–14.

Psalm 23

My shepherd (23:1). See the sidebar “God as Shepherd.”

Shadow of death (23:4). See the sidebar “Death and the Underworld” at Psalm 30.

Rod … staff (23:4). The “rod” was a clublike weapon used to defend a flock against predators; the same word is used for a royal “scepter” (see comments on 2:9). The “staff” could also serve as a weapon, but it was used to prod sheep in the right direction—hence a metaphor of divine guidance.

Prepare a table (23:5). To set out food was a gesture of hospitality (Gen. 18:1–8; Ex. 2:18–20).127 To do so in front of someone (enemies) publicly establishes the right relationship that exists between host (in this case God) and the guest (the psalmist). Perhaps the image of Yahweh as a protective shepherd king continues here (cf. 2 Sam. 9:7; 2 Kings 25:27–30).128

Stone relief from the palace of Ashurbanipal. Ashurbanipal and his queen feast in a garden following the defeat and death of the Elamite king Teumman at the battle of Til-Tuba in 653. Teumman’s head is hanging in the tree on the left.

Werner Forman Archive/The British Museum

Anoint … with oil (23:5). Olive oil could be used to treat dry or cracked skin, and so it was a sign of hospitality to offer oil to visitors. A text from an Aramaic-speaking community in Egypt (related culturally to Jews; ca. 300 B.C.) uses the word for oil to speak of invigorating an old man.129 In a diplomatic letter from Assurbanipal (ca. 650 B.C.) to vassal tribes in Arabia, he boasts of his good treatment of them: “The king of Assyria, your lord, put oil on you and turned his friendly face towards you.”130 Thus, the psalmist is refreshed by being in God’s hospitable presence.

I will dwell … forever (23:6). “Goodness” throughout one’s lifetime (23:6a) means continuous enjoyment of worship in the temple, a longing expressed in Mesopotamian hymns and prayers as well (see comments on 27:4). In ancient Sumer, worshipers dedicated statues to stand in the temple, symbolizing the individual’s continuous presence before their god.131

Sumerian votive figure is placed in temple, perpetually in the presence of deity.

Kim Walton, courtesy of the Oriental Institute Museum

Psalm 24

He founded it upon the seas (24:2). The ancients described their world in terms of what they saw (“phenomenologically”) rather than in modern scientific terms.132 From Egypt to the ancient Far East, people viewed the earth as floating on a cosmic ocean (see comments on 104:5).133 In the Mesopotamian story of Etana, the hero flies to the highest heaven on the back of an eagle, observing the earth below at various stages along the way. From his “bird’s-eye view,” the earth appears flat, bordered on all sides by mountains that divide the land from the encircling sea, in one instance described as an irrigation ditch.134

Babylonian map of the world depicts a circular ocean

Caryn Reeder, courtesy of the British Museum

In 24:2, the Hebrew word translated “waters” is literally “rivers.” In the geographical perspective of the ancient Israelite, the deep waters of the sea may have been thought of as a river encircling the earth. A ninth-century B.C. Babylonian map represents the earth as a circular disk surrounded by another circle named on the map as “ocean.”135 This word is qualified by another term meaning “river.”136 In other words, the sea moved in currents like a river (cf. Jonah 2:3, where “currents” is the same word translated “waters” in Ps. 24:2).

In the Baal myth, Baal’s victory over the god Yamm (meaning “sea”; cf. the sidebar “The Baal Epic” at Ps. 29) resulted in his elevation to kingship, which was symbolized in the construction of a palace (temple) for him on his holy mountain. In Psalm 24, Yahweh is the true king, based on the fact that he is the sovereign Creator of the universe, who holds the earth firm in the midst of “the seas.”

Who may ascend the hill? (24:3). The temple of Yahweh was built on a hilltop above the rest of the city (see comment on 48:2). Thus, going to worship at the temple involved a modest ascent. The temple mount was the place of God’s throne, which is relevant in this psalm’s call to praise God’s kingship (see comments on 15:1).

O you gates (24:7). Gates to cities and temples served as important stations of activity in worship festivals and processions. Examples from Emar (an important city in Syria) and Nineveh illustrate how a worship procession would pause at a gate in order to make offerings.137

There are no indications that offerings were made at gates during processionals in the Old Testament. But the manner in which the gates to the city and temple are addressed in this psalm suggests that they were important elements in some manner. Perhaps the ark of the covenant was carried out of the city and back in on special occasions, which would fit the divine warrior theme in this psalm (see comment on 68:24; 132:8). The gates probably symbolized the city as a whole, which was to lift up its countenance (“head”), meaning to be joyful and honored (cf. Gen. 40:12–13; Ps. 27:6; 110:7).

Mighty in battle (24:8). God’s role as a warrior is an important theme in the Bible (see comments on 7:13; 18:2–14).

Psalm 25

To you (25:1). The first letter of this phrase is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, beginning an “acrostic” (see the sidebar “Acrostic Psalms” at Ps. 111).

Put to shame (25:2). In ancient texts, a common expression that sums up the emotions of defeat was “shame.” An Assyrian prayer to the god Nabu begs: “I am one in a weak condition, who fears you; do not let me come to shame in the assembly!”138 Similarly, promises of deliverance are expressed in terms of not allowing the pious one to come to shame.139

Sins of my youth (25:7). The rashness of youthful behavior is proverbial in all cultures and is generally met with special patience and leniency by society. Mesopotamian laments also speak of the “sins of the youth,” with the hope that the deity will be merciful.140

Snare (25:15). See comments on 124:7; 140:5.

Psalm 26

I wash my hands (26:6). Mention of the “altar” and “house” of God indicates that a temple setting is in view, perhaps where the psalmist hopes for the vindication of judicial innocence before the assembly of worshipers (vv. 1, 11–12; see comments on 17:3). One of the functions of the high priest using the Urim and Thummim was to determine difficult cases (Ex. 28:30; Deut. 17:8–9). In the tabernacle and in Solomon’s temple there was a basin of water for priests to wash (Exod. 30:17–21; 1 Kings 7:23–26; 2 Chron. 4:6).

Laver by the cultic installation at Dan

Kim Walton

The psalmist’s reference to washing may allude to a similar ritual for any worshiper circulating in the court of worship. Evidence suggests that ritual washings were customary in temples from Phoenicia on the Mediterranean coast to Susa, east of Mesopotamia.141

Psalm 27

Stronghold (27:1). Fortifications in the ancient Near East are known from before 5000 B.C., as soon as rival, settled communities competed for resources necessitating military structures for defense.142 If a city had adequate supplies of food and water to endure a lengthy siege, it might withstand an attack indefinitely (Samaria fell after three years; 2 Kings 17:5).

Dwell in the house (27:4). Pious Mesopotamian worshipers expressed the same longing for continuous presence in the temple. This is illustrated in a Babylonian incantation prayer for deliverance from illness: “May I stand before you forever in worship, prayer, and devotion.”143 See also comments on 23:6.

Hide your face (27:9). See comment on 13:1.

Father and mother forsake (27:10). While social isolation, even from one’s family, is a common theme of laments (see comment on 31:11),144 this expression may allude to the physical loss of parents as a result of death, which at an emotional level is experienced as abandonment.

A parallel from the Babylonian Theodicy may help clarify the distress: “I was the youngest child when fate claimed (my) father, my mother who bore me departed to the land of no return, my father and mother left me, and with no one my guardian!”145 The phrase “left me” is equivalent between the two languages (Heb. ʿzb = Akkad. ʿzb); yet unlike the plight of the Mesopotamian worshiper, the psalmist has confidence that Yahweh will in the end be at hand.146

Psalm 28

Lift … hands (28:2). Among postures of worship, lifting hands in prayer is commonly mentioned and portrayed pictographically in ancient Near Eastern cultures. Mesopotamians possessed an entire category of prayers named “prayers with raised hands.”147 The meaning of the gesture is submission and hopeful appeal. This is illustrated in Egyptian art, which depicts people bringing tribute to the divine pharaoh with upraised hand and also imploring an Egyptian royal servant for favor.148

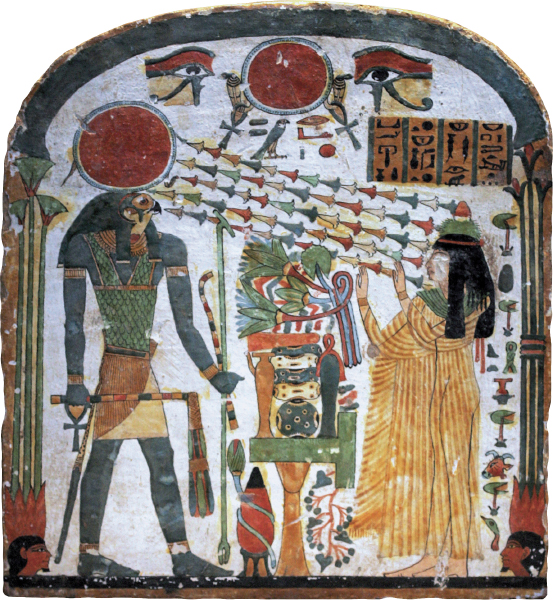

Stele of the Lady Taperet praying to Ra, 22nd dynasty

Rama/Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of the Louvre

Anointed one (28:8). See comments on 2:2.

Psalm 29

O mighty ones (29:1). The Hebrew phrase can be translated more literally “sons of gods,” which refers to the supernatural beings (“angels” in modern terms) that inhabit the heavenly realm. The NIV emphasizes their lofty power; but their identity and abode are more clearly expressed in 89:5–7, where the same Hebrew expression is translated “heavenly beings” and is found in poetic parallel with the “assembly of the holy ones,” who praise Yahweh in the heavenly realm.

In the ancient Near Eastern worldview, the universe was inhabited by divine beings (gods, goddesses, and lesser spirits) and human beings. The realm of divine beings was organized like a human royal court, with a chief god presiding and the others comprising his council. This divine assembly met to render judgments concerning the world, although in Old Testament thought, Yahweh is in no need of “council” from his court (see comments on 82:1). What is especially relevant for Psalm 29 is the fact that these other divine beings, who according to 89:5–12 cannot compare to the Creator God, are called upon to bow down in worship before him in 29:1–3 (cf. 97:7), just as humans are commanded in 96:7–9.

Baal Epic (Baal and Yamm)

Rama/Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of the Louvre

The voice of the Lord (29:3). The myths of the Canaanite god Baal provide important background for appreciating the message of this psalm (see the sidebar “The Baal Epic”). While speculative claims that Psalm 29 is actually an adaptation of a Canaanite hymn to Baal overstate the evidence (see the sidebar “Psalm 29—A Canaanite Hymn?”), numerous phrases and ideas in Psalm 29 seem to allude to Baal stories, beginning with the reference to a deity giving “voice” in the form of thunder. Baal, as storm god, spoke with thunder: “And may he give his voice [Ugar. ql = Heb. qôl] in the clouds, may he flash to the earth lightning” (cf. 29:7).149 Psalm 29 refers to the “voice of the Lord” seven times, which may allude to the proverbial seven thunders and lightnings of Baal.150

Dead cedar in the middle of the cedar forest in Lebanon

Tomi A. Liljeqvist

The imagery throughout these verses describes a mighty storm that forms over the waters of the Mediterranean Sea, sweeps inland across the forested mountains of Lebanon in the north, and rolls on to the desert of Kadesh. However, rather than viewed as a revelation of Baal, these powerful phenomena of the weather testify to the majesty of Israel’s Creator God, Yahweh.

Over the waters (29:3). Literally “the many waters,” this expression refers to what is unruly in creation (see comments on 93:3–4; 144:7), and the sea was the epitome of such chaotic forces. In the Baal story, the enemy sea god may also be called “god of many waters.”151 By alluding to Baal’s victory over the sea, however, it is evident in this psalm that Yahweh, not Baal, presides over such forces.

Cedars of Lebanon (29:5). These forested mountains were famous in the ancient Near East as the best source of stout timber for construction. Kings from Egypt to Mesopotamia would boast that they gathered lumber for building projects from faraway Lebanon. Tiglath-pileser I claims: “I marched to Mount Lebanon. I cut down (and) carried off cedar beams for the temple of the gods.”152 The Egyptian official Wenamun’s venture in Lebanon was prompted by his quest for great timber.153 Even David and Solomon looked to these forests as the best source of timber for the royal palace and Yahweh’s temple (2 Sam. 5:11; 1 Kings 5:6–9).

In the Baal myth, cedars from Lebanon and Sirion are the materials for his palace.154 When Baal speaks, his enemies flee to the woods: “Baal eyes the East, his hand indeed shakes, with a cedar in his right hand.”155 A letter from a vassal king in Palestine to his Egyptian overlord (ca. 1350 B.C.) addresses the deified Pharaoh as one “who gives forth his cry in the sky like Baal, and all the land is frightened at his cry.”156 Psalm 29:9 speaks of the oaks twisting and the foliage being stripped from the forest. These stalwart trees shatter before the power of God.

Lebanon … Sirion (29:6). “Sirion” is another name for Mount Hermon (Deut. 3:9) in the mountain range immediately inland from the coastal mountains of Lebanon. Hence they are coupled together poetically in both the Baal myth and here. At 9,232 feet, Sirion was among the highest mountains in the vicinity of Israel. These mighty mountain ranges quake when God speaks, being likened to powerful young bulls and oxen skipping about (cf. 114:4).

A snow-covered Mt. Hermon

Almog/Wikimedia Commons

Strikes with flashes of lightning (29:7). Lightning was commonly viewed as a divine weapon (see comments on 18:12; 97:2–5). Baal in Canaanite art had a lightning bolt in his hand.157 But Psalm 29 stresses that it is Yahweh who can strike with the power of lightning.

Desert of Kadesh (29:8). The most familiar reference to Kadesh in the Old Testament is the southern desert site of Kadesh Barnea, where the Israelites camped during their journey in the Sinai peninsula (Num. 13:26; Deut. 1:19, 46). If this location is in view, then the imagery of Psalm 29 tracks the storm from the mountains in the north to the desert regions south of Judah.

However, another possible referent is the region near Qadesh north of Damascus on the Orontes River. This fits well with the other northern geographical references in the psalm, and this possible location (“wilderness of Kadesh”; mdbr kdš) is known from a Ugaritic text, fitting with the other allusions in the psalm to these traditions.158 In this case, the more general translation of the Hebrew word used in 29:8 (midbar, “wilderness”) is in view.

Enthroned over the flood … as King (29:10). The psalmist concludes by returning to the scene of his heavenly court. The word translated “temple” (v. 9) is the word for a “palace”; when a palace happens to be that of a deity, it is a temple. In the Baal myth, the victory over the waters of chaos earns for the god of the thunderstorm both kingship and the right to have a palace temple: “So Baal is enthroned in his house.”159

Shamash, the sun god, enthroned over the waters (rippling at bottom of relief)

Z. Radovan/www.BibleLandPictures.com

In 29:10, Yahweh sits enthroned in his temple over the “flood.” The particular word used here for “flood” is used elsewhere only of the great flood in the time of Noah (Gen. 6:17; 7:10). This story was well known in the ancient Near East, and a flood is the ultimate divine weapon, undoing the ordered creation for the destruction of humanity.160 The god Marduk defeated the enemy goddess, Tiamat, in part with “the Deluge, his great weapon.”161

Perhaps alluding to the flood story known in his own Mesopotamian tradition, the Assyrian king Sennacherib boasted that his destruction of Babylon was comparable to this great event: “I made its destruction more complete than that by a flood” [or “the flood”].162 Mesopotamian literature extols the power of the warrior god Ninurta by reference to his use of the flood as a weapon and his “riding” upon the flood.163

Yahweh’s power not only exceeds that of the “many waters” (29:3); his kingship over the flood ascribes to Yahweh the highest possible sovereignty. Having taken up royal residence in his temple, Yahweh himself is at rest.164 On this basis the psalmist expresses confidence that Yahweh can give peace to his people in the midst of any imaginable chaos. It is not Baal but Yahweh who is truly King (see comment on 99:1).165

Psalm 30

Only a moment (30:5). The desperate need for forgiveness and deliverance is common enough in human longing. An Egyptian prayer hopes in terms similar to the psalmist: “The lord of Thebes does not spend the day in wrath, when he rages, it is but for a moment, and nothing is left. The breeze has turned to us in grace, Amun has come, carried in his breath of life.”166

What gain? (30:9). See comment on 88:10.