Psalm 81

Music (81:2). See comments on music and instruments at Psalms 96 and 150.

New Moon … Feast (81:3). The New Moon (i.e., the first day of the month), combined with the description of a full moon, the fourteenth day, points to the autumn religious festival as the setting of this psalm. This feast opened on the first day of the seventh month (September/October) with a trumpet call for a sacred assembly. It included the Day of Atonement on the tenth day and culminated with the week-long Feast of Tabernacles beginning on the fifteenth (Lev. 23:23–44; Num. 29:1–40). See the sidebar “Pilgrim Psalms” at Psalm 120.

Language we did not understand (81:5). See comment on 114:1.

He says (81:6). While this phrase is not in the Hebrew text, the NIV correctly adds it in order to introduce the words of the Lord spoken by a prophet at the festival.371 Prophetic ministry during temple worship was probably common. Assyrian temple prophets served at covenant renewal festivals, and this type of background fits a call to observe the basic commandments.372 See comment on 50:7.

Meribah (81:7). See comment on 95:8.

Psalm 82

Great assembly (82:1). This Hebrew expression can be rendered more literally “assembly of God” or “divine assembly” (“congregation of God,” NASB mg.; “divine council,” NRSV, ESV). Yahweh, the God of Israel, stands at the head of an assembly of heavenly beings, which in Old Testament texts are usually called “gods” (i.e., supernatural beings; see comments on 29:1; 89:5; 96:4–5; 103:20) but in New Testament and modern theology are called “angels” or “demons.” A narrative description of this setting is Job 1:6 and 2:1, where these beings appear before God who is holding court (see also 1 Kings 22:19). The Hebrew phrase in Job is literally “sons of God” (NASB, ESV), rendered “angels” in the NIV and “heavenly beings” in the NRSV.

Pharaoh seated with the gods at Abu Simbel

Yvan Huberman

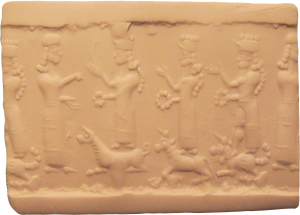

The concept of a divine council was also well known among Israel’s Canaanite neighbors and in the religion of Mesopotamia.373 In the Baal Epic (see the sidebar “Baal Epic” at Ps. 29), the god Yamm sends messengers who stand before the chief god El and the rest of the gods and goddesses assembled together to render a judgment on Yamm’s request.374

Meeting of the great Mesopotamian gods

Kim Walton, courtesy of the Oriental Institute Museum

Likewise, the assembly of the gods in Mesopotamia meets to determine the fate of kings and peoples.375 Particularly relevant to verse 7 is the decision of the divine assembly to sentence another god to death, such as in the Mesopotamian creation myths.376 By way of contrast, in Egyptian mythology, the god Osiris is welcomed to the afterlife by the divine assembly, called the “Council of Maat” (Egyptian maʿat = “justice”; see comments on 85:10).377

Foundations of the earth (82:5). While this concept usually refers to the divine ordering of creation (see comments on 24:2; 104:5), it is also used as a metaphor for social order (cf. 75:3; comment on 11:3).

I said, “You are ‘gods’ ” (82:6–7). God speaks here through the words of a temple prophet (see comment on 50:7). He is rendering a verdict of destruction on the heavenly beings who have transgressed the divinely ordained social order. An important aspect of the ancient viewpoint here is that human rulers make decisions that mirror the actions of the “gods.” The term “gods” is used both of supernatural beings and human rulers as their agents (see comment on 45:6). Therefore, divine retribution reaches into both the human and the heavenly realms in order to vindicate the victims of injustice and oppression (see comments on 58:1).

Psalm 83

Alliance (83:5–8). The reference to Assyria points to the general period of Assyria’s westward expansion (ca. 750–700 B.C.), although no specific event known outside this psalm corresponds to this list of nations. The number of nations (ten) may suggest a stereotypical list of enemies. Mention of the Assyrian empire at the end punctuates the list of nine other enemies.

The feet of king Netjerikhet (Zoser of later tradition) resting on the “Nine Bows” representing Egypt’s outside enemies, as well as the “lapwings” symbolising the Egyptian people.

Werner Forman Archive/The Egyptian Museum, Cairo

From earliest times, Egyptian scribes used the term “Nine Bows” to refer to nine nations in the region of Egypt, at times including Egypt itself. Over time the convention changed so that the specific nations listed were enemies of the Egyptian king. The nations listed often described a circle around Egypt, although they were not always in geographical order.378 The number of nations named also varied at times. For example, the list of “Nine Bows” on Merneptah’s Stele (ca. 1207 B.C.) numbered only eight, including Israel.379 The lists of foreign enemies in Old Testament prophetic books as well as in Psalms 60 and 83 may follow a similar custom.380

Edom, Moab, and Ammon were kingdoms southeast, east and northeast of the Dead Sea, respectively (Moab and Ammon being descendants of Lot). Ishmaelites and Hagrites were Bedouin tribes in the Arabian Desert east of Palestine, and Amalek refers to tribes located to the south. Gebal may refer to a city in Phoenicia (northwest of ancient Israel); however, there is evidence of a Gebal in the region of Edom, which better fits the other places immediately before and after this name in the list.381 Philistia bordered Israel and Judah on the west and Tyre was a major city in Phoenicia to the northwest. Assyria controlled territories to the north and northeast. Thus, all sides of Israel are covered here.

Midian … Sisera and Jabin (83:9). During the judges period, God intervened to help Gideon defeat the Midianites (Judg. 6–7), a tribal group later associated with the Ishmaelites. About this same time, Sisera and Jabin, from Hazor to the north of Israel, were defeated by Deborah and Barak (Judg. 4–5). By selecting these examples, the psalmist alludes to famous victories in geographical regions corresponding to the list of enemies in verses 5–8.

Oreb … Zalmunna (83:11). Oreb, Zeeb, Zebah, and Zalmunna were nobles killed in Gideon’s battle against the Midianites (Judg. 7:25; 8:3, 12, 21).

You alone (83:18). With the exception of the Egyptian king Akhenaten, the kings and religious leaders of the ancient Near East either worshiped many gods or else favored one deity without demeaning the worth of others (see comments on 86:8). The Hittite king Mursili II (ca. 1300 B.C.) pleaded with the gods in the face of a disastrous plague that he was careful not to neglect the temples of any deity: “I busied myself with all the gods. I did not pick out any single temple.”382 For the psalmist, there is only one supreme God.

Psalm 84

How lovely is your dwelling place (84:1). Hymns that extol holy cities and their temples are known from the ancient Near East (see the sidebar “Hymns to Holy Cities” at Ps. 48). Psalm 84 concentrates on the delights of a visit to Jerusalem and its temple, where God dwelt. The language of “courts” is consistent with the view of a temple as the “palace” of God (see comment on 100:4). A similar sentiment is illustrated in an Egyptian prayer from ca. 1200 B.C. in which a religious pilgrim lingers in the temple court.383

A home … near your altar (84:3). While the Most Holy Place containing the ark of God’s presence was the most sacred place in the temple, it was accessible only to the high priest (Lev. 16:1–2); and the altar of incense within the Holy Place could only be approached by a priest (2 Chron. 26:16–18). Therefore, the altar of sacrifice in the temple court was the most important center of activity for the average worshiper. The psalmist marvels at the good fortune of even a small bird to have a nest so near, probably tucked into a niche somewhere on the structure of the sanctuary itself overlooking the court and altar. Even more fortunate are the priests, who have the privilege of living in the temple compound (v. 4).

Pilgrimage … the Valley of Baca (84:5–6). At the great festivals, Israelites journeyed from their homes to worship at the temple in Jerusalem (see the sidebar “Songs of Ascent” at Ps. 121). The phrase “Valley of Baca” is difficult. It may be a geographic designation for an unidentified stream valley that offered an approach to the hills of Jerusalem. Some, however, suggest that this phrase is symbolic (“Valley of Weeping”), reflecting an interpretation of the Hebrew word bākā ʾ as “weeping, tears.”384

Our shield … your anointed one (84:9). As in 89:18, the king is identified with the shield as an image of protection (on “anointed one,” see comment on 2:2; for “shield” see 3:3).

A sun and shield (84:11). If the king is a “shield” (v. 9), this metaphor is also applicable to God, whom the king represents and who is called “King” in verse 3. The identification of the sun with a chief deity was common in the ancient Near East. In Egypt the sun god (Re) was the most celebrated deity, responsible for creation and life; the Mesopotamian sun god (Shamash) defended justice (see comments on Ps. 19 and 104). Both a sun god and sun goddess were predominant for the Hittites.385 The sun was only a servant goddess in Ugaritic myth but is nevertheless attested.386

Hittite god Sharruma shields King Tudhaliya IV with an arm around him and holds him by the wrist to guide him.

M. Willis Monroe

Not surprisingly, the worship of the sun emerged in ancient Israel or, at least, solar symbols were attached in an idolatrous manner to the worship of Yahweh (2 Kings 23:5, 11; Ezek. 8:16).387 Using artwork in a style borrowed from Egypt that displayed solar images such as winged sun disks, high officials in Israel put them on their signet rings and jewelry.388 A similar type of royal art was common in Assyria as well, which featured the national god, Aššur, represented as a winged solar disk. The assimilation of such art into Israelite popular culture may have accompanied the idolatrous adaptation of solar symbols in worship.

King Meli-shipak presents his daughter before the goddess Nanaya.

Marie-Lan Nguyen /Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of the Louvre

However, the poetic use of verbal images of the sun to speak of the character of Yahweh was neither idolatrous nor inappropriate. The sun is naturally associated with healing, protection, and life-giving properties, and so it lends itself to such metaphors (Mal. 4:2). The psalmist here draws on these associations of the sun to describe God’s goodness (see comments on Ps. 104:2), especially in regard to his kingship.389 The purely poetic use of the sun, without necessarily associating it with solar worship, is illustrated by a similar metaphorical use in a second millennium B.C. Mesopotamian hymn To the Goddess [Nanay], Sun of her People.390

Winged sun-disk at Medinet Habu shielding cartouches of Ramesses III

Neil Madden

Psalm 85

I will listen (85:8). This may refer to a prophet in the temple waiting for a message from God, which in this psalm then comprises verses 9–13 (see comment on 50:7).

Righteousness and peace (85:10). Like the joining of “love” (steadfast love) and “faithfulness” (Ex. 34:6; Ps. 89:1–2), the coupling of “righteousness” and “peace” is appropriate. Righteousness is first and foremost associated with social justice (Deut. 16:18–20, where the word translated “justice” in v. 20 is the same word for “righteousness” in Ps. 85:10). The word “peace” means wholeness or well-being (72:7, where the word “prosperity” [social well-being] is the same word translated “peace” in Ps. 85:10). Peace results when righteousness prevails (Isa. 32:16–17).

A similar pairing of these two concepts was shared by the Egyptians, who expressed the combination with one word (maʿat). For the Egyptians, maʿat was the natural order of the universe, “the way things ought to be.”391 It can be translated “order” or “justice,” so it embraces social justice leading to prosperous life for the community. A good illustration of this is found in the speeches of The Eloquent Peasant, in which a peasant appeals for justice from a local magistrate. His poem links the execution of social “justice” (maʿat) with the “fair wind” that accompanies a smooth and prosperous sail on the sea.392 When chaos plagues Egyptian society, it is due to the absence of maʿat in the king’s rule.393 In 85:10, righteousness and peace “kiss” when God blesses his people (see also comment on 72:3).

Psalm 86

Among the gods (86:8). In ancient Near Eastern hymns, proclaiming the incomparability of a god or goddess is well attested. Whichever of the great gods a person was worshiping would be the “greatest” at that particular moment. For example, in one hymn the Assyrian king Assurbanipal (ca. 650 B.C.) calls his national god, Aššur, “lord of the gods,” surpassing all other gods, who themselves cannot fully comprehend him.394 In another hymn, he proclaims Marduk as the most high and most powerful, whose deeds make him lord of the gods.395 Elsewhere, he claims that the goddess Ishtar has “no equal among the great gods.”396 Some expressions of worship to the Egyptian sun god declare his incomparability: “one without parallel,”397 “the one of surpassing power” relative to the other gods,398 “who conceals himself from all the gods … there is no comprehending him.”399

A scene from from the tomb of Ramose depicts the deified sun-disk, Aten, with extending rays bringing divine gifts.

Manfred Näder, Gabana Studios, Germany

But such expressions of praise did not exclude the worship other deities. For a brief period in Egypt, the king Akhenaten (ca. 1350 B.C.) destroyed religious shrines and attempted to obliterate the recognition of all gods other than the deity Aten, even prohibiting the use of the divine plural in official documents.400 Composed at this time, the Hymn to the Aten addresses the deity: “O sole god, without another beside him!”401 In the context of this statement, the composer affirms the creation of human beings and other creatures of the earth but makes no mention of other gods, as do other Egyptian hymns.402 However, the same expression “sole god” was used before and after Akhenaten’s time.403 So it is only in conjunction with the other evidence that one might suspect Akhenaten promoted a form of “monotheism.”

Inconsistent with his monotheism is the fact that he and his queen were themselves worshiped as intermediaries to this god, and there are hints of a form of pantheism in his theology.404 In any event, it differed from the Israelite conception of God, which was inextricably linked with ethical accountability and the cosmic battle against evil.405 This emphasis emerges in Psalm 86, which calls the nations to account (v. 9), the individual to submission (v. 11), and the wicked to judgment (v. 17). In contrast to the confession of 86:15, Akhenaten’s sole god was not the compassionate savior of the one in need.406 For the psalmist, Yahweh’s incomparability means that he alone is “God” (v. 10), so that all others in the supernatural realm exist on a lower order of being (see comments on 29:1; 82:1).

A sign (86:17). Perhaps the request here is best understood as an expectation of prophetic response in the context of worship (see comment on 50:7). The demonstration of God’s favor by some visible or tangible form will vindicate the psalmist in the sight of his enemies. This concept is illustrated in a letter from a Canaanite king to Pharaoh (ca. 1350 B.C.). The king expresses his wish for a gift from Pharaoh as a visible symbol that he enjoys Pharoah’s favor: “Bestow a gift upon his servant so that our enemies may see (it) and be humiliated.”407

Psalm 87

His foundation on the holy mountain (87:1). In Old Testament thought, Jerusalem (also called Zion, v. 2) was at the center of God’s kingdom and the world (see comments on Ps. 48). The psalmist here marvels at the stability of Jerusalem resulting from Yahweh’s presence in his temple, which has become the anchor point for the entire cosmos (see the sidebar “Sacred Space” at Ps. 84). This thought is similar to a Babylonian hymn in praise of the god Nabu’s temple at Borsippa: “Its summit reaches the clouds, its well-founded roots thrust to the netherworld.”408

Rahab and Babylon (87:4). Babylon was one of the oldest and most highly esteemed cities in Mesopotamia (Gen. 10:10), so in this psalm it represents the peoples from this region of the ancient Near East. The identification of Rahab is not as clear. In some contexts, the name refers to the chaos serpent (see comments on 74:13–14; 89:9–10). However, the names of mythical monsters can be used symbolically for an enemy nation; and here Rahab is another name for Egypt (Isa. 30:7), the great empire to Israel’s southwest.

Philistia … Tyre … Cush (87:4). Philistia, the homeland of Israel’s traditional enemy during the judges period, was located to the west, along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Further north, also on the coast, was Tyre, part of the Phoenician homeland and a vestige of the original Canaanites. Cush was south of Egypt, but at times it dominated the entire Nile Valley. The psalmist, then, chooses the names of significant cities and nations to represent foreign peoples who will acknowledge Israel’s God, Yahweh, whose holy city is Zion (cf. 99:1–2).

Register (87:6). In Babylonia during the first millennium B.C., people were identified by city of origin: a “son of city X.” Having one’s birth in a particular city meant citizenship with all of the protection and privileges associated with it. In particular, residents of a city and its district were under the divine protection of the patron deity of that city. Some cities were exempt from taxes or forced labor, since they were identified as the holy cities of important deities.409 Holy cities also afforded a place of asylum for one seeking justice. Divine protection may even have extended in some cases to the animals.410

Evidence of these customs ranges from Egypt to Hatti and Mesopotamia and from the earliest records of the third millennium B.C. to the first century B.C. This custom may clarify the status conferred by Yahweh on foreign peoples who worship him. They have chosen to worship Yahweh, and in effect they are under protection as citizens born in his holy city, Zion.

My fountains (87:7). A common image in ancient Near Eastern art is a deity holding a vessel from which waters flow, bringing blessing to the worshipers.411 Perhaps this lyric, sung by converts to the God of Zion, alludes to the idea that the dwelling place of God is the origin of all that blesses life (see comment on 46:4).

Gudea, prince of Lagash with flowing vase

Z. Radovan/www.BibleLandPictures.com

Psalm 88

Grave … Destruction (88:3–7, 11). For these images related to death and burial, see the sidebar “Death and the Underworld” at Psalm 30.

Dead rise up and praise (88:10). The glorification of God’s name on earth comes through the praises of his people (22:3; lit., “enthroned on the praises of Israel,” ESV, NASB). Conversely, the dead contribute nothing in this regard. This notion forms the basis of a natural appeal to God for intervention. A similar plea is echoed in a Mesopotamian prayer to Marduk:

Do not destroy the servant who is your handiwork;

What is the profit in one who has turned into clay?

It is a living servant who reveres his master;

What benefit is dead dust to a god?412

This very human perspective is also evident in Hittite laments.413

Psalm 89

I have made a covenant (89:3–4, 26–37). The theme of God’s covenant with David is introduced in verses 3–4 and expanded in the prophetic proclamation that begins in verse 19. David and his descendants were chosen by Yahweh to rule on the throne over the people of Israel (see 2 Sam. 7; Ps. 132:11–12). The covenant announced in these prophetic speeches promises unconditionally that David’s dynasty will always be the rightful heirs to the throne. However, individual descendants who do not follow God’s laws may be removed from kingship.

Unconditional and conditional elements are compatible in ancient Near Eastern treaties and wills, with wording similar to that of 2 Samuel 7; Psalms 89 and 132.414 For example, a great king might grant to a loyal subject certain guarantees of property. The property would always belong to the family; however, in the future any disloyal individual could be disciplined by the great king and lose his right to the land. Nevertheless, the land remained in the possession of the family line. While the form of these royal grants is not an exact parallel with the Davidic covenant,415 the similar language illustrates how unconditional and conditional themes work in compatible fashion in the same document. Another important feature of these covenants is the family terminology (see the sidebar “Divine Sonship” at Ps. 2).

The assembly of the holy ones (89:5). For this concept and its parallel expressions “heavenly beings” and “council of the holy ones” in verses 6–7, see 29:1; 82:1; 103:20.

You rule over the surging sea (89:9–10). These images of God as Creator allude to his sovereignty over the forces of chaos. In the ancient Near East, the uncontrollable oceans were associated with hostile powers that threaten life on the inhabited land. This concept is expressed in several ancient myths, such as Enuma Elish (also known as The Epic of Creation), in which the god Marduk rose as champion and king of the gods to defeat Tiamat, a goddess of watery chaos.416 From Ugarit, stories about the god Baal feature a battle in which he defeats Yamm, the god of the sea, and assumes kingship.417 Rahab (v. 10), whom Yahweh slays, corresponds to these water chaos monsters (Job 26:12; Isa. 51:9–10; see comment on Ps. 74:13–14).

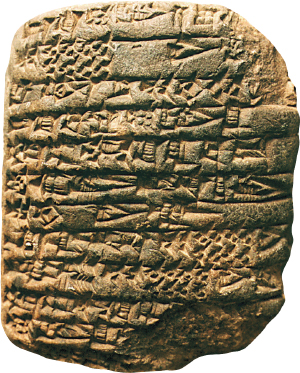

Enuma Elish—the Babylonian creation epic

Doug Bookman/www.BiblePlaces.com

After victory, Marduk creates the world, and Baal assures the stability of the cycles of nature. In both Enuma Elish and the Ugaritic story, the victory has implications for the political realm of the peoples who celebrated the myths. In Babylon, Marduk’s ascension as king of the gods corresponds to the rise of Babylon as the major power in Mesopotamia.418 The victory of Baal over the sea is recalled in a prophetic message to the king of Mari, where the god Adad claims: “I restored you to the throne of your father’s house, and the weapons with which I fought with Sea I handed you. I anointed you with the oil of my luminosity, nobody will offer resistance to you.”419 Thus, victory in the divine realm undergirded the stability of the earthly political realm.420

Yahweh’s power as Creator and his sovereignty over the forces of chaos are appropriate in this hymn, which extols his power and justice as the basis of Davidic kingship. By alluding to the myths, the psalmist affirms that it is Yahweh, not the gods of the other nations, who is supreme over creation and kingship.

Created the north and the south (89:12). The phrase “the north and the south” is a poetic way of saying that God created everything, by naming two extremities in order to include everything in between (cf. also Ezek. 20:47; 21:4). The word for “north” (ṣāpôn) may be significant for another reason, for this same word is the name of a high mountain in Syria to the north of Israel (Zaphon). Although Yahweh’s dwelling is most often associated with Mount Zion in Jerusalem, his presence is sometimes attached to other high mountains, like Zaphon (see comment on 48:2). The “south” was also the place of Yahweh’s mountain dwelling (Deut. 33:2).

In the ancient Near East, gods were often associated with high places, especially mountains, and worshiped there. Canaanite myth placed Baal’s palace on Mount Zaphon.421 Mount Tabor and Mount Hermon in northern Israel were likewise ancient worship sites.422 But the psalmist praises Yahweh that he is the one who created these places, and they stand prominently as landmarks to his praise.

Righteousness and justice are the foundation of your throne (89:14). Frequently depicted on the pedestal of Egyptian thrones is the hieroglyph for justice (see comment on 85:10), conveying the importance of this value to the rule of a good king423 (cf. also 72:1).

Maat, goddess of justice, truth, and order, seated on a plinth that represents the primeval mound of creation

Werner Forman Archive/Sold at Christie’s, 1998

Our shield belongs to the Lord (89:18). The shield is a symbol of protection; here it is an image for the king to whom the people look for their security (see comments on 3:3; 84:9, 11). The people affirm their dependence on the king and ultimately on Yahweh, to whom the king belongs but whose downfall this psalm laments.

Once you spoke in a vision (89:19). The word “vision” indicates that the ideas expressed in the following verses originated from prophetic speech (Isa. 1:1; Hos. 12:10). The royal promises to David and his descendants began with the prophet Nathan (2 Sam. 7), through whom Yahweh announced his covenant, and are found in other prophetic psalms (see Ps. 2; 110; 132:11–18). Such oracles were sometimes uttered in a temple setting, which fits well the background of the psalms. In 89:19, the use of ḥasîdîm (“faithful people”) refers to the community gathered for worship (“saints” in 30:4; 52:9; 145:10; 149:1; “consecrated ones” in 50:5). For many of the expressions in this prophetic speech, see the sidebar “Prophetic Assurance to the King.”

I have found David my servant … I have anointed him (89:20). See comments on 2:2.

I will also appoint him my firstborn (89:27). As the eldest son in a family, the “firstborn” had customary right to a major share of the inheritance (Deut. 21:15–17) and took leadership of the family clan after the father’s death (Gen. 27). In the ancient Near East, the eldest son of a king normally became the next king. However, exceptions are known and sometimes led to political turmoil. For example, the firstborn son of Sennacherib (704–681 B.C.), Ardi-Mulissi, was replaced by a younger son, Esarhaddon, as the heir to the throne. The former assassinated his father and civil war ensued.424 Similarly, political tension resulted from David’s selection of Solomon over Adonijah (1 Kings 1). If the Davidic king is the “firstborn” heir of the Creator of the world, then he is also the preeminent king (“most exalted,” v. 27) over all world rulers.

His throne … like the sun … like the moon (89:36–37). Because of their enduring presence in the universe, the imagery of sun and moon were used in royal inscriptions for the stability of a king’s dynasty.425 A letter to Esarhaddon (ca. 670 B.C.) expresses the wish: “As firmly as the moon and the sun are established in the sky, so firmly may the kingship of the king, my lord, and his descendants be established.”426 In Psalm 89, they are likened to witnesses to the covenant, thereby ensuring its validity for all time.

Psalm 90

Return to dust (90:3). Death is decreed. According to Mesopotamian myth, their chief god, Enlil, became annoyed by the noise stemming from the ever-growing human population. After the flood was sent by the gods to wipe out humanity and thus alleviate the noise, population growth was limited by withholding immortality from humankind. In the story of the death of Gilgamesh, the god Enki describes how after the flood “we [the gods] swore that mankind should not have life eternal.”427 The psalmist recognizes that divine judgment and death are the result of sin (v. 8). For the concept of “dust,” see comments on 104:29–30.

Seventy years (90:10). As early as 100 B.C., the apocryphal Book of Jubilees (23:15) contrasts the pre-flood life spans approaching a thousand years (Ps. 90:4) with the post-flood expectancy of seventy years (v. 10). A similar chronological schema is preserved in the Sumerian King List, which records the reigns of kings in the tens of thousands of years before the flood but diminishing to hundreds of years and then tens of years after the flood.428

Antediluvian king list

The Schøyen Collection MS 2855, Oslo and London

On the basis of human skeletal remains, anthropologists have estimated the life span of people living in Palestine during biblical times. A little over 40 percent reached adulthood (20–49 years of age) and nearly 10 percent lived beyond fifty years.429 Ancient Egyptian tradition idealizes the maximum age at 110, as Pharaoh Amenmesses (ca. 1200 B.C.) hopes: “until I reach 110 years (of age) upon earth, like any righteous man.”430 But more realistically, Egyptian tradition also sets the prime of life between forty to sixty years.431 Mesopotamian expectations set forty years as “prime” with ninety years as a maximum.432 Records show that scribes and even many slaves lived sixty to eighty years.433 The mother of Babylonian king Nabonidus lived 104 years.434 These cultural norms all accord with the expectation of the psalmist.

Establish the work (90:17). The ancient Israelites recognized the ephemeral nature of life and human endeavor (vv. 3–6; Isa. 40:6–7; Eccl. 2:11, 16), but a similar humility also marked Mesopotamian thought. A Mesopotamian wisdom text that treats the transitory nature of life states: “[Whatever] men do does not last forever. Mankind and their achievements alike come to an end.”435 The text admonishes the reader to attend to his god. In Psalm 90:17, a confident trust breaks through that God is able to make human efforts count for good.