Psalm 71

Depths of the earth (71:20). See the sidebar “Death and the Underworld” at Psalm 30.

Harp … lyre (71:22). See comment on 150:3.

Psalm 72

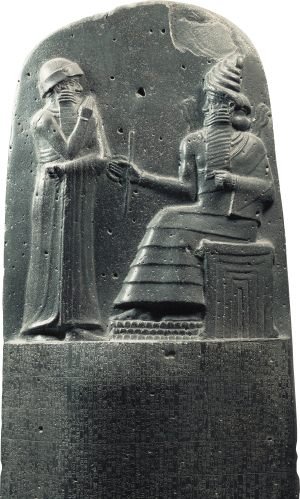

Endow the king (72:1). In the ancient Near East, the ideal king was endowed with justice as a gift from the gods. King Hammurabi of Babylon, who reigned eight hundred years before Israelite kings, introduced his famous law collection with the claim that he had been appointed by the gods “to make justice prevail” for the “well-being of the people” and “to prevent the strong from oppressing the weak.”307 The top of the stele on which Hammurabi’s laws were written features a portrait of Hammurabi receiving authority from Shamash, the god of justice (see Ps. 19).308 A close parallel to Psalm 72 is Assurbanipal’s Coronation Hymn, a prayer used in the enthronement ritual of Assurbanipal, an Assyrian king contemporary with the last kings of Judah.309 The ritual includes the prayer: “May eloquence, understanding, truth and justice be given to him as a gift.”310

Hammurabi standing before Shamash

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY, courtesy of the Louvre

The mountains will bring prosperity (72:3). Woven together throughout Psalm 72 are the themes of justice, peace, and domestic prosperity. In the prologue to Hammurabi’s laws and especially in the epilogue, the king boasts that his just rule brings peace and prosperity to the cities of his realm.311 Immediately following the prayer for justice in Assurbanipal’s Coronation Hymn, the priest asks that the king’s dominion might be characterized by prosperity (abundance of grain; cf. 72:16) and peace (Assyrian salīmu is akin to the Heb. šālôm in 72:3).312 Injustice resulted in social chaos (see comment on 94:20).

In Egyptian thought, the execution of justice by the king expels chaos from creation, bringing harmony and order to the land: “Re [the creator- and sun-god] has established the king on the earth of the living forever and ever; to speak justice to the people and to satisfy the gods, to realize Maʿat (justice, world order) and drive away Isfet (chaos).”313 Egyptian texts often extol the king as one who “lives by Maʿat” (see comment on 85:10).314

Thus, in both Mesopotamia and Egypt, people set their hope on the king for justice and prosperity. In Egypt, this revolved around a pharaoh who participated in the company of the gods and mediated divine blessing to humanity; but this hope never focused beyond the currently living king, except late in Egyptian history (ca. 300 B.C.) when expectations arose among some that a king would arise to restore the former glory of Egypt.315

Similarly, Mesopotamians did not conceive of a future king who would usher in an ideal age. People considered only their contemporary king as the agent of the gods who ideally maintained a prosperous social order.316 In contrast, in the Old Testament one finds a progressively developing theme of hope for a future, worldwide kingdom, ruled by a Davidic king on behalf of Yahweh.317 This theme began to unfold in part through prophetic, royal psalms, such as Psalm 72 (see also comments on Ps. 2 and 110).318

Defend the afflicted (72:4). Care for the weak members of society is the practical test of a just and good government throughout the ancient Near East. Hammurabi’s claim in this regard is noted above. In the Ugaritic story of King Kirta, the king is rebuked for failure to “pursue the widow’s case,” “take up the wretched’s claim,” “expel the poor’s oppressor,” and “feed the orphan.”319 In the Egyptian Instructions to King Merikare, the king is exhorted, “Do justice, then you endure on earth; calm the weeper, don’t oppress the widow.”320

He will endure (72:5). Along with the hope for justice and prosperity, Psalm 72 anticipates a long reign. This strikes another parallel with Assurbanipal’s Coronation Hymn, where the priest prays that the god Aššur will “lengthen your days and years.”321 Using the sun and moon as metaphors of an enduring reign is common in royal literature (see comment on 89:36–37).322 The Phoenician royal servant Azatiwada wishes his good name to be remembered “forever like the name of the sun and the moon” (cf. 72:17).323

He will be like rain (72:6). In an agriculturally based society, rain is essential to a prosperous economy. The coronation prayer for Assurbanipal asks, “In his years may there constantly be rain from the heavens and flood from the (underground) source!”324 In Psalm 72, the king himself is likened to these precious waters that bring life to the earth. This theme occurs again in verse 16, where prayer is offered for abundant grain, like the vegetation that flourishes on the well-watered mountains of Lebanon.

Detail from coffin of Nespawershepi, chief scribe of the Temple of Amun. Rain falls from the sky goddess Nut, bringing forth seedlings from the mummified body of Osiris, illustrating his role as a sign of resurrection and new life.

Werner Forman Archive/The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

From sea to sea (72:8). Frequently in poetry, the author uses two extremes to express the totality of everything in between (a figure of speech called “merism”). In royal literature, it stresses the unlimited extent of a king’s dominion over geographic space and time (see “sunrise to sunset” in the sidebar “Prophetic Assurance to the King” at Ps. 89). There may be an allusion here to the geographical perspective of the ancient Near East in which the earth was surrounded by the sea (see comment on 24:2). Thus, “sea to sea” meant across the entire world.

The “River” (72:8) may refer to the Euphrates (cf. 1 Kings 4:21); but if a more universal view is intended, then “river” could be understood as synonymous with the “sea” (i.e., the cosmic ocean viewed as a current of water, like a river, encircling the earth). By comparison, in Ugaritic literature the god of the sea, “Prince Yamm” (Heb. word for “sea” is yam) was also called “Judge River (Nahar)” (Heb. word for “river” is nahar).325 If this viewpoint is maintained, then in Psalm 72:8 the phrases “sea to sea” and “river to the ends of the earth” are parallel expressions for the distance from one end of the world to the other.326

The people named in this psalm (see the sidebar “The Peoples of Psalm 72”) represent the most remote and hostile places. From the farthest reaches of the Mediterranean Sea in the west to the coastal shores to the south (the Red Sea), and including the “wild” desert in between, all people will submit to the king, and the most distant nations will bring tribute to him. This is yet another way of expressing the geographical expanse of the king’s dominion “from sea to sea” (i.e., the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea, parts of the great ocean that surrounded the earth). Anticipation of an extensive kingdom in this psalm has a counterpart in Assurbanipal’s Coronation Hymn: “Spread your land wide at your feet.”327

Long may he live (72:15). The coronation prayer for Assurbanipal asks the deities, “Give our lord Assurbanipal long days, copious years.”328 Stereotypical interjections were used in Egyptian inscriptions, asking life for the king (e.g., “given life, duration, dominion, may he live like Re”).329 A long reign for a just king meant enduring peace and a good life for his people.

The god gives Pharaoh the ankh sign, which symbolizes long life.

Frederick J. Mabie

Gold from Sheba (72:15). While there are gold resources on the Arabian Peninsula (the most likely location of Sheba), the maritime trade that took place in the Red Sea channeled some of the famous gold resources of Nubia330 (south of Egypt) through Sheba (Ezek. 27:22). Gold was customarily part of the tribute paid to great kings (see 2 Kings 18:14–16 and Sennacherib’s corresponding record of this tribute).331

Psalm 73

Mouths lay claim to heaven … earth (73:9). A common figure of speech called a “merism” occurs when two opposites are mentioned to express the whole. The pairing of the two words “heaven” and “earth” is common in the Old Testament (e.g., Gen. 1:1; Deut. 32:1; Job 20:27; 38:33; Ps. 96:11), but a parallel including this pair with “lips” and “tongue” appears in the Baal Epic, when the god of death, Mot, threatens to swallow Baal by opening his mouth so wide that one lip touches heaven, the other earth, and the tongue touches the stars. In 73:9, “heaven” and “earth” are paired to suggest that the wicked have extended their ownership (and power) to control everything.

Psalm 74

Sheep of your pasture (74:1). This is a common metaphor in city laments (see sidebar). The deity is like a shepherd who has lived in a hut (i.e., the temple) within the sheepfold (i.e., the city).332 Abandonment of the city is tantamount to abandoning the people who are like sheep: “the herder was abandoning his byre [i.e., barn], and his sheepfold, to the winds … at the temple close [the god] Enlil was abandoning Nippur, and his sheepfold, to the winds” (cf. 83:12).333

Where you dwelt (74:2). In Sumerian city laments, only after a deity has abandoned his or her city is it vulnerable to attack. See comments on 46:5; 47:8; 48:1.

Destruction … the sanctuary (74:3). The destruction of Jerusalem and the temple (586 B.C.; see 2 Kings 25:8–17) lies at the heart of this psalm. While there are no extrabiblical descriptions of this event, the Babylonian Chronicle does record the capture of Jerusalem and deportation of King Jehoiakin eleven years earlier in 597 B.C. (2 Kings 24:8–17), at which time the temple treasures were plundered.334

Standards as signs (74:4). The word translated “standards” can refer to a military banner with insignia to distinguish different troop units (see comments on 60:4, where a different word is used for the same object). Because these insignia bore symbols of foreign gods, raising them at the site of the temple was particularly sacrilegious (cf. v. 10).

Procession of soldiers with standards from Deir el Bahri

Manfred Näder, Gabana Studios, Germany

Their axes (74:6). The Lament of Ur draws on the same images one might expect of such destruction: into the temple “big copper axes chewed.”335 Other lines describe the fires that consumed buildings and people alike. These graphic images stir deep feelings for the tragedy.

Every place (74:8). It is unlikely that the psalmist would lament the destruction of illegitimate places of worship, whether within the temple complex or at various sites throughout the land (2 Kings 21:1–6; 23:1–20). Perhaps these were simply special meeting places for prayer.336 In cities and villages of the ancient Near East, local shrines other than central, regional temple complexes accommodated the needs of the common people.337 Even when orthodox worship prevailed in Jerusalem, one might expect multiple gathering places that did not provide for sacrifices or other unauthorized rituals in competition with the Jerusalem temple. Unfortunately, the only places for religious gathering that would leave a clear trace in the archaeological record are those with illicit features such as altars or figurines.338

Sea … monster … Leviathan (74:13–14). In order to underscore the power of God to intervene if he so chooses, the psalmist alludes to a well-known myth in the ancient Near East about the triumph of a god over the sea serpent. The closest neighbor to ancient Israel that preserved this myth is the Canaanites, whose religion is best represented by the texts from Ugarit (ca. 1300 B.C.). In their Baal Epic, Baal defeats the sea god Yamm (Heb. yam means “sea”) and thereby earns the title king, together with the right to a palace temple (see the sidebar “Baal Epic” at Ps. 29). The epic refers to Yamm using the same names and imagery as 74:13–14: “When you killed Litan (Ugar. ltn = Heb. liwyātān, “Leviathan”), the Fleeing Serpent, you annihilated the Twisty Serpent, The Potentate with Seven Heads.”339

Hero slays seven-headed monster with flames coming off its back.

Iraq National Museum, Baghdad, photo courtesy the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago

In the Baal Epic, the sea is portrayed as a multiheaded serpent, corresponding to the “heads” (plural) in 74:13. Yamm is also called by the same name, “monster,” used of Yahweh’s opponent (Ugar. tnn = Heb. tannîn).340 A Ugaritic magical text might also describe the scattering of Yamm’s corpse in the desert (cf. 74:14), although that text is difficult at this point to be certain of this meaning.341

The use of this myth as an analogy to illustrate the power of Yahweh can be found in other Old Testament passages.342 Isaiah describes Yahweh’s final victory over evil in terms of slaying “Leviathan … monster of the sea” (Isa. 27:1). He also uses the same two adjectives to describe the serpent that are used in the Ugaritic text quoted above (“fleeing … gliding” and “twisting … coiling”). Job 3:8 and 41:1–34 refer to Leviathan, and Job 7:12 equates the sea (yam) with the monster (tannîn).

Other biblical texts combine allusions to this myth with another name for the sea monster, “Rahab” (Job 9:13; 26:12–13; Ps. 89:9–10; Isa. 51:9–10). This name is used as a derogatory name for Egypt (Ps. 87:4; Isa. 30:7), perhaps because the mythic analogy of splitting the sea fit well with the victory over Egypt during the crossing of the Sea of Reeds. Isaiah explicitly associated the exodus with Yahweh’s victory over the sea monster, Rahab (Isa. 51:9–10). Probably, the psalmist’s use of this imagery in connection with God’s salvation “from of old” (Ps. 74:12) also alludes in part to the exodus deliverance. However, the mention of the sun and moon, the emergence of land, and the seasons in verses 15–17 (for “ever flowing rivers,” see comments on 93:3–4) suggests that the psalmist has in mind the molding of all creation as a demonstration of God’s supreme power.

While the Canaanite myth does not connect Baal’s triumph with creation, similar images in Egypt and Mesopotamia do. The Egyptian wisdom text The Instruction of Merikare speaks of the well-being of humankind, tended by the god who created sky and earth and “subdued the water monster.”343 The Egyptian sun god, on his sailing journey each night across the waters of the underworld, defeats a serpent who threatens the order of creation and therefore the potential for afterlife: “[The sun-god] who sails across heaven, traverses the Underworld…. The harpoon is in the Serpent, who falls to God’s knife … no enemy of his exists in heaven or on earth.”344

One Mesopotamian account of creation features the god Marduk rising to kingship through his defeat of the ocean goddess (see comments on 89:9–10). Another text advances the reputation of the god Nergal by reporting his battle against an ocean dragon.345 Other evidence for shared knowledge of the Baal myth in Mesopotamia includes a prophetic text from Mari (ca. 1800 B.C.), which reports a speech of the god Adad (=Baal) who “fought with the Sea.”346 Numerous iconographical images from Mesopotamia of battle between a god and a multiheaded dragon have survived.347

By using this culturally relevant analogy, the psalmist intensifies his appeal for Yahweh to act. If common myth claimed that the gods attained their kingship and palace through a battle against the sea, should not Yahweh restore his own temple, the symbol of his kingship, for he is the true Creator and Victor over all the forces of chaos and evil? See also comment on 104:26, where the creature is a mere plaything of Yahweh.

Psalm 75

Appointed time (75:2). The word translated “appointed time” might be any agreed assembly place (Josh. 8:14) or specified time (Ex. 9:5). The prophet Habakkuk uses this term for God’s chosen time of judgment (Hab. 2:3), and in Psalm 102:13 God’s time for intervention is simultaneously a time of deliverance for his people.

However, the term can also refer to the assembled feasts of the religious calendar occurring three times a year: Passover, Unleavened Bread, and the Feast of Weeks (Pentecost) in the spring and the Feast of Booths in the fall (Ex. 23:15; Lev. 23:2; see the sidebar “Pilgrim Psalms” at Ps. 120). Given the worship setting of Psalm 75 and its identification as prophetic speech (see comment on 50:7), the backdrop for this psalm may be a judgment/salvation speech delivered at such a religious gathering (cf. 50:5; 81:3, 8; 95:6–9).

Pillars (75:3). For “pillars” see comment on 104:5. The metaphor “foundations” here extends to the social order, as the following context suggests (see comments at 11:3; 82:5).

Babylonian boundary marker depicts chaos creature in the depths among the pillars that support the earth.

Rama/Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of the Louvre

Horns (75:4). Horns were symbols of strength and therefore a basis for boasting (see comment on 18:2).

Cup … foaming wine (75:8). When wine ferments, it produces a froth from the released gases, so the metaphor perhaps suggests a particularly well-fermented product.348 The word picture is expanded with the description “mixed.” At times wine was mixed with water, but spices were often used to increase the pungency of the drink (Song 8:2).349 The allure and potentially damaging effect is described in Proverbs 23:29–35, so it serves as a fitting metaphor of judgment (Ps. 60:3; Isa. 51:17; Jer. 25:15, 27).350 The “dregs” are the sediment at the bottom of the jar.

Psalm 76

Salem (76:2). This is an abbreviated form of the name Jerusalem, identified as such because of the parallelism with “Zion.” Salem means “peace.” The same abbreviation is used in Genesis 14:18 as the royal city of Melchizedek, who met Abraham after his return from the war against the five kings. This psalm, which celebrates Yahweh’s protection of Jerusalem, is closely related to the “Songs of Zion” (see the sidebar “Hymns to Holy Cities” at Ps. 48).

He broke … weapons of war (76:3). Psalm 76 alludes to a siege of Jerusalem broken by the intervention of Yahweh. It is not clearly identifiable with any known battle in Old Testament history, but Sennacherib’s siege of Jerusalem in 701 B.C. (2 Kings 18:17–19:37) would match the description in the psalm.

Psalm 77

The waters saw you (77:16). The psalms sometimes speak of the exodus in terms of a cosmic battle between Yahweh and unruly personified forces, such as turbulent waters, which in other ancient Near Eastern texts are hostile gods and goddesses (see comments on 29:3; 93:3–4; 74:13–14).

Thunder … lightning (77:17–18). These natural phenomena, together with the earthquake, are commonly associated with the appearance of a divine warrior (see comments on 18:7–15). Strictly speaking, the meteorological events happened during the exodus plagues (Ex. 9:23–24), and the earthquake was an added phenomenon when Yahweh appeared on Mount Sinai (Ex. 19:16–19). However, these descriptions converge in this psalm’s poetic depiction of Yahweh, the divine warrior, throwing back the unruly waters of the sea during Israel’s escape from the Egyptian army (see comment on Ps. 106:7). For Yahweh’s appearance as a warrior at the crossing of the Sea of Reeds, see Exodus 15:3.

The sea (77:19). See comments on 106:7.

Giant footprints of deity at the temple at ʿAin Dara

John Monson

Footprints (77:19). The gods and goddess of the other nations in the Near East were portrayed in various animal and human forms. Of interest is the discovery of giant footprints carved into the threshold of a temple at ʿAin Dara in Syria (tenth to eighth-century B.C.).351 The footprints symbolize the deity stepping from the entrance into the inner sanctuary. Israel’s God revealed himself only in the cloud and pillar of fire.

Psalm 78

Parables (78:2). Wisdom themes are not foreign to hymnic literature (see comment on 49:1). In the most basic sense, a “parable” is a comparison between two things, but the term is used more broadly for any saying that reflects on the concerns of wisdom (see comment on 49:4, where it is translated “proverb” and is echoed by the word “riddle”). Here the concern is passing on to children the lessons of the fathers (cf. Prov. 1:8). A similar value is expressed in the Egyptian Instruction of Ptahhotep:

He will speak likewise to his children,

Renewing the teaching of his father.

Every man teaches as he acts,

He will speak to the children,

So that they will speak to their children.352

Men of Ephraim (78:9). Ephraim was the second son born to Joseph, son of Jacob, in Egypt (Gen. 41:50–52). Near the end of Jacob’s life, Joseph brought his two sons to their grandfather for blessing (48:1–20). Jacob declared that they would become tribal heads, so that their names would attach to the tribes alongside Jacob’s other sons. In addition, Ephraim was set in prominence over Joseph’s firstborn son, Manasseh. In time, Ephraim’s tribe became the dominant group among the northern tribes of Israel, so that “Ephraim” became synonymous with all northern Israel.

When addressing the northern kingdom, the prophet Hosea uses Ephraim’s name for the whole (e.g., Hos. 5:3; 6:4; 7:1; 10:6; 11:12). Psalm 78 is concerned with the downfall of the northern kingdom and the transfer of prominence to Judah as the place of God’s dwelling (vv. 59–60, 67–68). The use of “Ephraim” at this early point in the psalm (v. 9) signals this emphasis.

Zoan (78:12). The geographical starting point for the exodus was Pi-Ramesses (cf. Ex. 1:11), now identified as Qantir, which was the administrative capital for the eastern delta region of Egypt and royal residence at the time. By the first millennium B.C., this city was abandoned and its building materials cannibalized for construction in a new regional center called Tanis a short distance to the north. Even at the time of the exodus, the Egyptians used the term “Field of Zoan” for this latter area. Therefore, the psalmist uses a geographical designation for the eastern delta region recognized by his first millennium contemporaries.353

Blood … hail … lightning (78:44–48). See comments on 105:28–33.

Grasshopper (78:46–47). See comments on 105:34–35.

Ham (78:51). See comment on 105:23.

High places (78:58). Before the centralization of worship at the Jerusalem temple, Yahweh was worshiped at various locations. Some of these shrines are called “high places” (1 Sam. 9:11–25; 10:5; 1 Kings 3:2–4). After the building of the central sanctuary, sacrifice at these locations was no longer legitimate, and continuation of the practice became inseparably linked with the worship of other gods (1 Kings 11:7; 2 Kings 23:1–20). Even before the temple was built, not all of these worship shrines were orthodox (e.g., Judg. 6:24–26)—hence the condemnation in Psalm 78:58.

High place outside the gate at Dan

Kim Walton

The exact description and archaeological identification of these cultic places is unclear.354 As the name suggests, high places included hilltop shrines where images of various gods or goddesses were set up (1 Kings 14:23). But they were also located in valleys (Jer. 7:31; 32:35). Some featured altars for burning incense (2 Kings 17:11; 23:8) or offering sacrifices (1 Kings 12:31–33; 22:43).355 What was probably the central high place at Dan has been excavated (1 Kings 12:29–31). It was a large hilltop platform, approximately sixty feet across, approached by a sacrificial altar.356

Because of the connection between “high places” and shrines at city gates (2 Kings 23:8), excavations at Dan also illustrate another type of high place. These consisted of a short platform the size of a bed located in city gateways. Stone pillars, representing deities, stood at the far end.357 In some cases, a high place featured enclosed buildings for the rituals and personnel of the shrine, perhaps more like a temple (1 Kings 12:31; 13:32, “shrine,” where the Heb. word for “house” is used). The high place where Samuel worshiped included an eating hall that could seat thirty people (1 Sam. 9:22).

Tabernacle of Shiloh (78:60). Located in the center of the territory held by Ephraim, Shiloh was the initial resting place for the ark (Josh. 18:1; 1 Sam. 1:3). Because of Israel’s rebellion (1 Sam. 2–4), God abandoned the location of his dwelling among the northern tribes in favor of Jerusalem, the capital city of David in the southern kingdom of Judah (Ps. 78:67–72; see comment on 132:13). Archaeological excavations confirm that Shiloh was a major economic and administrative center, destroyed violently by fire in the mid-eleventh century B.C., probably at the hands of the Philistines.358

He built his sanctuary (78:69). The theme that gods are ultimately the builders of their own temples is frequently associated in the ancient Near East with the notion that such a temple is rooted in the cosmic realm (either in the realm below the earth’s surface or in heaven). This is a poetic way of affirming its secure and enduring qualities.359

Shepherd (78:70–71). For this royal metaphor, see the sidebar “God as Shepherd” at Psalm 23. The Assyrian king Assurnasirpal (ca. 1050 B.C.) speaks to the goddess Ishtar: “You took me from the mountains and named me to be shepherd of the peoples.”360

Psalm 79

Reduced Jerusalem (79:1). This historical event is the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonian army in 586 B.C. (see comments on 74:1–6). Psalm 79 is similar to city laments known from ancient Mesopotamia (see the sidebar “City Laments” at Ps. 74).

Dead bodies … blood (79:2–3). One common feature of city laments is the graphic description of the fate of the city’s inhabitants. The Lament for Ur reports:

its people—not potsherds—littered its sides …

in its high gate … corpses were piled …

in the (open) spaces … people were stacked in heaps.

The country’s blood filled all holes.361

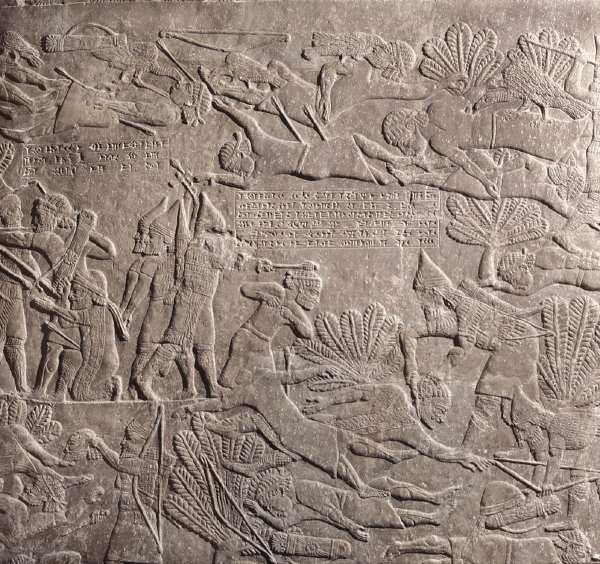

“They have given the dead bodies of your servants as food to the birds of the air.” At the top, birds devour carcasses of the slain Elamites at Til-Tuba.

Werner Forman Archive/The British Museum

Pour out your wrath (79:6). While city laments acknowledge that the destruction was the result of a divine decision, they also often contain a section calling for divine retribution on the enemy who showed no limit in their rampage.362

We … will praise you (79:13). A concluding vow in a city lament is the portrait of praise that will result if the city is restored. The Lament for Ur closes with the hope: “O Nanna!—in your city again restored they will offer up praise to you!”363

Psalm 80

Shepherd (80:1). See the sidebar “God as Shepherd” at Psalm 23.

Joseph (80:1). Joseph, one of the twelve sons of Jacob, was the father of Ephraim and Manasseh. Ephraim became the dominant tribe of the northern alliance and so the entire northern kingdom became known as “Ephraim” or “Joseph” (see comment on 78:9). Like Psalm 78, this psalm seems particularly interested in events affecting these northern tribes (vv. 12–13, 16). Perhaps the Assyrian invasions of 732 and 722 B.C. lie in the background to this lament, when the north was decimated (2 Kings 15:29; 17:3–4).

In 734–732 B.C., Tiglath-pileser III campaigned against Syria and the northern kingdom of Israel. He was drawn in part by tribute from the Judean king Ahaz, who was anxious for the Assyrians to intervene against the king of Israel, who threatened Ahaz for not joining the anti-Assyrian coalition (2 Kings 16:5–9; Isa. 7:1–2). Most of Israel was annexed to the Assyrian empire with the vassal king Hoshea left on the throne of the rump state of Samaria.364

Hoshea’s submission lasted seven years. In 725 B.C., he rebelled against Assyria, resulting in a three-year seige of Samaria and eventuating in its destructive downfall and ravaging under Shalmaneser V and Sargon II.365 Many citizens of Israel sought refuge in Judea/Jerusalem during these war-torn years, and this psalm may have served to reorient their theology and allegiance to the temple and king in Jerusalem. While Benjamin (v. 2) is sometimes more closely associated with the southern kingdom (1 Kings 12:21; 2 Chron. 15:2), Benjamin was the only brother of Joseph through Rachel; as a border tribe between north and south, its identity and fate was also bound to the north.

Enthroned … cherubim (80:1). See comment on 99:1.

Face shine (80:3, 7, 19). This refrain finds an echo in v. 14, where God’s act of restoration is parallel to looking down from heaven and watching in a protective manner. So the metaphor of “shining” can be linked to the image of God as the sun (see comments on 84:11).

God Almighty (80:4). This Hebrew expression has traditionally been translated “God of hosts,” or when coupled with the divine name Yahweh, “Lord of hosts” (KJV; NASB; RSV; NRSV; ESV). The word for “hosts” is associated with armies (Judg. 4:2; 1 Kings 2:5; Isa. 34:2). By extension, the same word refers to the “army” of heavenly beings whom Yahweh commands for his service (Ps. 89:5–8; see comment on 103:20–21). The psalmist calls for God to intervene militarily on behalf of his people, utilizing his heavenly army on their behalf (59:5).

The Ugaritic god of war, Rashap, is called in one text “Rashap of the Army” (Ugar. ṣbʾ = Heb. ṣbʾ).366 There may also be a connection between the imagery of God as a shining sun (vv. 3, 7, 19) and his ability to intervene with his heavenly “host/army.” A conceptual parallel might be found in a letter from a Canaanite king to the Egyptian pharaoh (ca. 1350 B.C.).367 The Canaanite king has readied his troops for battle to serve the pharaoh, whom he calls “sun of thousands.”368 A related letter uses the image for the pharaoh as the sun “over thousands” shining forth over the horizon to muster troops.369

Bread of tears (80:5). The trauma was so long and severe, it is as though the people’s daily bread is their hardship—a metaphor known also from Mesopotamian texts.370

Boars (80:13). Not only were boars vicious, powerful animals in the wild, but they were unclean for eating (Lev. 11:7; Deut. 14:8, translated “pig”). The irony of the image is that an unclean animal is destroying the food of God’s people.

Dismounted horseman attacks a boar with a lance.

Werner Forman Archive/The British Museum