The Credential and the Compostela

The Camino de Santiago is a great adventure, a sacred pilgrimage in the footsteps of millions of others intertwined with an outdoor trek across northern Spain. Leading from the town of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port on the border with France, it travels west for 780 kilometers (485 miles), traversing daunting mountains, lush river valleys, sweeping plains, striated vineyards, and rolling hills swaying with wheat to the purported tomb of Saint James the Greater in Santiago de Compostela. And the path doesn’t really stop there: It continues all the way to the rugged shores of the Atlantic.

The Camino is a rare chance in the busy world for solitude and self-reflection, even for self-reinvention, while traveling in the company of pilgrims from more than 140 nations and while encountering engaging and generous locals who have lived on and served the Camino for generations. It is a path of strange trail magic, where solutions are delivered just as you need them, and where someone walking past spontaneously gives the perfect answer to the very question rolling around in your head.

The Camino is also a paradox. When a person becomes a pilgrim—pèlerin in French, peregrino in Spanish—and temporarily disconnects from normal life to go for a long walk, he or she enters into a deep experience of presence and connectedness on many levels, with nature, with others, and with him- or herself. Many peregrinos marvel that the Camino naturally cultivates such a profound experience, and with it, transformation, just by walking.

Officially a Christian pilgrimage that is over 1,200 years old, the Camino is older than this. Humans have long traversed the lands crossed by the Camino, along southwestern France and northern Spain. They left signs—stone tools, painted caves, rock art, dolmens, hilltop settlements, prehistoric roads—and, only later, medieval towns and chapels. You still feel their footsteps as you step along the trail. Some locals claim that there is a special energy in the land itself, a ley line poetically tracing on the earth the path of the Milky Way seen by pilgrims in the night sky. It is a perfect melding of nature and culture, an outdoor adventure and a historic European grand tour.

1 Taking your first step on to the Camino in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port’s Rue de la Citadelle, a cobblestone path worn smooth by thousands of pilgrims over 900 years.

2 Crossing the Pyrenees on the way to Roncesvalles, with incredible views at the peak of Col de Lepoeder and Puerto de Ibañeta.

3 Joining the locals for pintxos in Pamplona or on Calle del Laurel in Logroño, where proprietors at each bar specialize in one distinctive tiny bite, or tapas in León’s Barrio Húmedo, the “wet quarter,” so named because it contains more than 100 bars.

4 Stepping inside the enigmatic, octagonal Santa María de Eunate, known as the “Church of 100 Doors,” which was constructed as a meditation on numbers held sacred by many ancient faiths.

5 Seeing grooves worn by Roman cart wheels as you walk across the Roman road and bridge as you leave Cirauqui.

6 Filling your scallop shell with local red wine at Bodegas Irache Wine Fountain, a relatively new Camino tradition that has quickly become a classic.

7 Visiting Iglesia de San Nicolás de Barí on the spring and autumn equinox, when a beam of sunlight perfectly illuminates a capital featuring a scene of Mary and her cousin Elizabeth.

8 Exploring the Atapuerca Archaeological Site, where archaeologists have unearthed 1.2-million-year-old human remains.

9 Standing inside the hauntingly romantic 12th-century San Antón Monastery Ruins, whose crumbling Gothic walls are overgrown with wild foliage.

10 Joining the nuns in sacred song at Albergue de Santa María in Carrión de los Condes.

11 Stepping into a swirl of color filtered through stained-glass windows at Catedral de Santa María de León.

12 Crossing the Puente del Paso Honroso, the 19-arched medieval bridge, made famous by a medieval jousting tournament, that leads to the village of Hospital de Órbigo.

13 Laying a stone at Cruz de Ferro on Monte Irago, the Camino’s highest point, as you silently enact a ritual of gratitude, forgiveness, or letting go.

14 Transporting to the era of knights, pilgrims, and passionate causes as you cross the drawbridge of the Castillo de los Templarios, a 12th- and 13th-century castle with thick, high walls and toothy ramparts.

15 watching the sunset and sunrise from O Cebreiro, a charming Galician village that marks the Camino’s third-highest point.

16 Exploring the Castro de Castromaior, a partially excavated hilltop fortress surrounded by concentric rings of protective walls.

17 Partaking in the ritual drinking of queimada, a heated concoction of spirits, sugar, coffee beans, and orange and lemon peels that’s said to quemar (burn) out all bad karma and energy and to prepare you to approach Santiago with a clean slate.

18 Arriving (at last!) at the Catedral de Santiago de Compostela, where you can deliver a traditional hug to the statue of Saint James before collecting your Compostela.

19 Taking a final pilgrimage to the coast, where you can gaze out on infinite sea and sky at the lighthouse at Cabo Finisterre or Virxe da Barca Sanctuary in Muxía.

20 Looking up at the Milky Way as you ponder the fact that the route of the Camino traces this celestial galaxy.

The Camino de Santiago today officially begins at Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, a stunning threshold at the Pyrenees and the border with France and Spain. You have two traditional options here: the popular Route Napoleon or the Route Valcarlos, which is used in winter and bad weather. Both ascend green-gray mountain peaks capped with snow and speckled with grazing sheep, leading to breathtaking views before descending to the huddled monastic hamlet of Roncesvalles. Throughout you are immersed in ancient Basque and Navarran culture, its hospitality, and its celebrated, colorful cuisine. This initial stretch is one of the most challenging on the Camino and includes the second-highest peak of the entire way. Especially from fall through spring, the weather can be prohibitive.

Beginning in Pamplona, Hemingway’s famed stomping ground, the Camino climbs and descends between open plains, high ridges, and steep ravines into wild and dynamic landscapes where early humans built dolmens and medieval masons created enigmatic and beautiful churches reflecting a mix of influences (pagan, Jewish, Christian, and Muslim), including Eunate, Torres del Rio, Cirauqui, Puente la Reina, and Estella. The Camino also traverses an ancient Roman road and takes you into wheat and wine country, including a surprise at the monastery of Irache: a fountain flowing with wine.

Defined by radiating vineyards and billowing wheat fields awash with red poppies in spring, the Camino treads along dark, rust-red earth that, toward Castile, turns gold. Here, you enter into remote pine forests rich with song birds and pass some of the path’s most spiritual monasteries, at Nájera, San Millan de la Cogolla, and San Juan de la Ortega.

Deep into Spain’s breadbasket, the Camino gradually climbs and enters the famous meseta—high plateau—of north-central Spain, with infinite swaying wheat fields where shepherds have tended their flocks for millennia. Land of hefty hilltop castles and frontier towns, this is El Cid country, saturated with epic poems of chivalrous (and roguish) knights. It is characterized by endless sky and wide horizons, which brings a different cadence to the walk. The food reflects this sturdiness with hearty farmer fare and strong wine. At an albergue in Carrión de los Condes, singing nuns invite you to listen to or join in sacred song. Burgos, at the begining of this route, is home to a world-class human evolution museum and also the gateway city to the Atapuerca archeological site, inhabited by humans 1.2 million years ago.

Mountainous terrain makes this one of the more challenging sections of the Camino. Slowly leaving the open meseta, the Camino passes into the multicolored mountains of León, so rich with minerals that ancient peoples, including Romans, built extensive roads here. After summiting Monte Irago, the Camino’s highest point, pilgrims can leave a ritual stone at the foot of the Cruz de Ferro iron cross—for many, one of the most meaningful experiences on the journey. You next trek into a vast valley and garden paradise of fruit orchards, vegetable gardens, and unique El Bierzo wines. The trail then enters narrow mountain valleys dotted with riverside villages, making a steep ascent into Galicia’s mountains at the ancient mountaintop village of O Cebreiro.

As one of the most convenient places to begin the final 100 kilometers (62 miles) of the Camino (required to earn a pilgrim’s certificate, the Compostela), Sarría is one of the most popular starting points. From here, the Camino leads through a green and mysterious realm defined by deeply folding river valleys and mountains covered in ancient oak and chestnut forest, some of the oldest in Iberia. Listen to locals tell stories of meigas (white witches) who cast healing cures, try queimada, a heated elixir of well-being offered to pilgrims, and sample celebrated cheeses from local cows (who are often more present on the trail than humans). You can also get a taste of the nearby sea in cafés serving Galicia’s famous spicy octopus, pulpo á feira.

The Camino ends here in this mythic medieval city, at the Catedral de Santiago de Compostela, where the body of Saint James is entombed. Pilgrims head straight to the cathedral to hug the statue of Santiago on the high altar. Afterward, wander arcaded cobblestone streets lined with granite churches, monasteries, museums, shops, and galleries built of gray granite, or visit the Mercado de Abastos, one of northern Spain’s most colorful and dynamic daily markets. The restaurants and cafés surrounding the cathedral showcase Galicia’s most tantalizing dishes from ocean, field, river, and mountain. One in particular, Casa Manolo, has been a popular pilgrim meeting spot for more than three decades.

The Camino doesn’t have to end at Saint James’s tomb in Santiago de Compostela: More and more pilgrims are trekking farther west toward the Atlantic coast towns of Finisterre and Muxía. At first, the journey through dense forest, undulating hills, and challenging small mountains feels deceptive: You can smell the ocean, but you can’t see it until you are almost upon it. At last, you meet finis terrae, earth’s end: a narrow finger of land with endless sky above, crashing waves below, and infinite watery horizon ahead. The coastline known as the Costa da Morte (“coast of death”) is rugged and dangerous, but that just adds to the filmic ending of a long walk across northern Spain. End-of-journey rituals include collecting a scallop shell from the beach or taking a purifying swim in the Atlantic.

Whenever you decide to begin your Camino, remember that rain—and need for rain gear, at minimum a rain poncho—is a year-round prospect. Also consider that the last 114 kilometers (71 miles), from Sarria to Santiago de Compostela, is the busiest section and you will feel a significant surge in numbers here. You may want to plan the timing of your Camino by thinking about when in your walk you will reach this benchmark.

Some 85 percent of annual trekkers walk the Camino from mid-May to mid-September. This is a time when you can carry the least amount of gear, but you do need to carry more water, watch for dehydration, and protect yourself from sun exposure. You’ll also have to deal with the crowds who can inundate the trail as well as the accommodations. But if you like warm weather, the company of other pilgrims, want to travel light, and are ready either to deal with the “bed race” or to book ahead, then this may be your season.

If you desire solitude, late November to early March can be ideal. You will need to carry more gear for warmth and also be prepared for around 60 percent of the albergues to be closed, usually from October until the week before Easter Sunday. This may demand that you stay in hotels, or walk farther to reach open albergues, but there is no bed race whatsoever. You may also need to carry more food, as some cafés and restaurants also close in winter.

For a balance between socializing and solitude, spring or autumn are ideal, and are also the most pleasant, moderate seasons to walk. Most seasonal albergues and cafés open around late March to early May, and stay open until around late September to mid-November. The bed race is also less intense. You will need more layers of clothing than in summer, but not as much as in winter.

The Camino is well supported so you can keep your pack weight light, ideally carrying no more than 10-15 percent of your body weight. Be sure your pack’s final weight includes the 2-3 pounds of water and food you need to carry each day. Of all the gear that you’ll bring, the three most important items are trekking shoes, such as light hiking shoes or sturdy cross trainers, that you’ve broken in and that fit you perfectly; socks designed for blister prevention; and a good, light moderate-sized pack. The Camino is pretty much a cash economy, and it’s a good strategy to have an average of €200 in your pocket, replenishing at ATMs along the way in cities, towns, and some large villages. You’ll find a packing checklist in the Essentials chapter.

How far to go is a personal matter based not only on how many days you have, but also on how far you want to walk each day. Plan shorter days at the beginning, so that your body can adjust to the terrain and to carrying a pack for 6-8 hours a day and also to prevent injuries—the early stages are when pilgrims are most likely to get hurt by pushing too hard too soon. As you walk, you’ll find your own rhythm and can add more kilometers a day or find your sweet spot. Some trekkers love going slow to take in the natural beauty and the small churches along the way, and may average 12-18 kilometers (7.5-11 miles) a day. Others get their high from rushing it, and cover 25-35 kilometers (15.5-22 miles) a day. The vast majority fall somewhere in between, averaging 21-25 kilometers (13-15.5 miles) per day.

Note also that while there are no public restrooms on the Camino, restrooms are available at bars and restaurants along the trail, where you can purchase a drink or snack to use their facilities; this is a good practice to keep the trail clean, take periodic breaks, and stay hydrated and fueled. Long stretches where there are few services are noted throughout this book.

walking toward León’s mountains and Rabanal del Camino

Part of the Camino’s magic is letting each day unfold unplanned and savoring the chance to travel without making reservations. However, some people may prefer to avoid racing for a bed at the end of a day of walking, especially during the peak months of May-September. You can either make reservations in advance or as you go. Good times to reserve ahead: to stay in the historic state-run paradors in León (Parador San Marcos) and Santiago de Compostela (Hostal de los Reyes Católicos); to break the Pyrenees crossing on the Route Napoleon into two days, book a night in Refuge Orisson; to offer ease on arrival, for your first night on the Camino; and to arrive in Santiago de Compostela, especially around July 25, Saint James’ feast day.

It can take anywhere from 31 to 45 days to walk the entire Camino from the French border at the Pyrenees to Santiago de Compostela, plus up to 7 days more to continue onward to the Atlantic coast. For many, this is impractical and intimidating. It need not be. Take a tip from the Spanish and French, who together make up 50 percent of the people who walk the Camino annually: Many often walk the trail in sections, returning a year or more later to pick up where they left off. Many others walk only that one portion and feel that it fulfilled their desire for sacred adventure. Even a three-day walk on the Camino is profound and transformative, and there are no right or wrong ways to walk it.

Most days you really won’t need to pack a lunch. Unless otherwise noted, stops for food are frequent along the trail, and many cafés offer options for good sandwiches, omelets, and salads. Most pilgrims feel more like having the larger meal at dinner anyway, and may rely on trail snacks such as dried fruit and nuts for their midday meal. Always carry plenty of water.

Settle in to your refuge (albergue, pilgrims’ hostel) or hotel and then head to the Pilgrims’ Welcome Office to pick up your pilgrim’s credential, elevation map, albergue listings, and good advice on trail conditions. Climb to the citadel for a first view of the mountains, visit the Eglise de Notre Dame and the pilgrims’ bridge, and then dine on the banks of the river Nive or enjoy a first ritual communal meal with fellow pilgrims at your refuge.

Begin your walk today! Ascend the Pyrenees via the Route Napoleon for endless views of mountain peaks spotted with black and white sheep. Stop in Orisson (7.6 km/4.8 mi after Saint-Jean) for lunch and to refill your water bottle (or even to spend the night if you’re tired). You’ll surmount Col de Lepoeder, the second-highest climb of the entire Camino, 12.8 kilometers (8 miles) after Orisson. (In bad weather and winter, use the Route Valcarlos instead, stopping in Valcarlos, 11.7 kilometers/7.3 mi after Saint-Jean, for lunch and a water-bottle refill or an overnight.)

The two routes rejoin near Roncesvalles. Descending into primordial beech forests, you’ll glimpse your first view of Spain and this town’s cream-colored and slate-roofed monastery. Celebrate the first and hardest day over dinner with fellow peregrinos in Roncesvalles’ albergue and the pilgrims’ mass in the 13th-century Iglesia de la Colegiata de Santa María. Alternatively, continue another 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) to the village of Burguete to stay in Hostal Burguete, where Hemingway stayed to go trout fishing in the Pyrenees.

Pass through rolling hills carpeted with wildflowers and fields inhabited by sturdy chestnut horses, then descend into a forest path of oak and beech to the Basque-Navarran village of Espinal and then Biskarreta, 11.6 kilometers (7.2 miles) after Roncesvalles. The latter offers a great terrace-side rest stop at Bar Dena Ona, where you should stop for a mid-morning snack or an early lunch.

stork family nesting on Plaza de San Juan in Burgos

After lunch, descend again into oak and pine forest along rising and falling rocky footpaths, then climb to views of the Pyrenees foothills at the Alto de Erro before arriving in the medieval riverside village of Zubiri.

green hills and forest on the way to Espinal

Shimmy along intimate footpaths that follow the foothills to the ridge guarding Pamplona. You will pass through the hamlet of Zuriain, 9.5 kilometers (6 miles) after Zubiri, where you can enjoy rest and pilgrim cheer at the riverside café of La Parada de Zuriain.

Follow the Arga river past small rural homestead gardens, fields of miniature horses or geese, and forest cover to the 13th-century hilltop church of San Esteban in Zabaldika, 3.5 kilometers (2.2 miles) after Zuriain. Climb its bell tower before taking the final footpath through wild flowers to Pamplona. Enter the city through its ancient towering fortress walls, soak up medieval Pamplona’s Gothic Catedral de Santa María, and step into Hemingway’s Pamplona at Café Iruña for a drink (and dinner) on the stately Plaza del Castillo.

Leave Pamplona, passing the university, and enter open hills flowing with wheat fields, rising to the steep climb at Alto del Perdón, 13.2 kilometers (8.2 miles) after Pamplona, where ceaseless wind animates the hilltop windmills. Then descend steeply into the ravine that leads toward the enigmatic round church of Santa María de Eunate, one of the most beautiful churches of the Camino. Pause here for half an hour or longer before climbing to the ridge-top town of Obanos, where you can enjoy the warm welcome and stay in the village center at Hostal Mamerto.

ironwork on Obanos’ Iglesia de San Juan Bautista

Kitchen gardens line the path to the town of Puente la Reina, 2.3 kilometers (1.5 miles) after Obanos. Here, the Camino joins the town’s central street, passing two unusual medieval churches—Iglesia del Crucifijo, with its goose-foot-shaped cross, and Iglesia de Santiago, with its Islamic-style doorway—before leaving the town over the arching medieval bridge that gives the town its name. After Puente la Reina, for about 8 kilometers (5 miles), you’ll dip into ravines and ridges, past wheat fields and almond groves, and though the hilltop village of Cirauqui. Leaving Cirauqui, you’ll actually be walking on surviving ancient Roman roads as you approach the village of Lorca.

After Lorca, you’ll pass the serene and poetic Ermita de San Miguel, worth a few minutes to visit. The path then leads uphill to Estella. Enter Estella as thousands have done before, passing the Iglesia de Santo Sepulcro, where Saint James smiles at you from the left of the central arch.

Estella is a good place for a rest day, especially if you arrive in time for the Thursday weekly market on the town’s two medieval squares. Highlights of Estella are the Romanesque churches of San Pedro de la Rúa (also possessing Islamic influences) and San Miguel, on one of the highest hills with expressive human sculptures. Visit the old mills on the riverbank, stop at a traditional woodworker’s shop right on the Camino, and enjoy a good meal on the main square, Plaza de los Fueros.

Leave Estella through 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) of rolling hills and native pine forest to reach the vineyards surrounding the Monasterio de Irache and the Bodegas Irache wine fountain, where you are invited to fill your scallop shell or bottle with a glass of local red wine. (Note that the fountain isn’t turned on until 9am). Continue through four more kilometers of pine forest to the hamlet of Azqueta, then continue on the gently weaving footpath past the medieval pointed arched cistern, Fuente de los Moros, to the vineyards and village of Villamayor de Monjardín. A climb to the fortified ruins of the Castillo de Monjardín, a medieval castle over earlier Roman fortifications, gives a remarkable view of the peak and valley landscape.

Continue through vineyards, pine forest, wheat fields, and olive groves on a softly descending path to Los Arcos, home of one of the powerful Black Madonnas of Spain in the 12th-century Iglesia de Santa María. Take 15 minutes to visit this church and see her on the high altar.

Enter a more exposed path of open wheat fields and pastureland dotted with grazing sheep on your way to the hilltop settlement of Torres del Río, 7.7 kilometers (4.8 miles) from Los Arcos. Allow a few minutes to visit the interior of the Iglesia del Santo Sepulcro and its octagonal dome designed after the mosque of Cordoba.

Leaving Torres del Rio, you’ll see vineyards from here to Viana and then cross into La Rioja and the region’s capital of Logroño. Stop for water, figs (when in season), and a passport stamp at Casa Felisia just before crossing the Puente de Piedra to enter the city.

From Logroño, you can take a day-long wine tour to surrounding vineyards with Rioja Like a Native, or make a day trip to the picturesque hilltop wine town of Laguardia to taste wine and explore dolmens—prehistoric standing stones—in the vineyards.

If you stay in Logroño, start your day exploring Logroño’s riverside center, which retains its medieval shape. Walk the labyrinth and inlaid mosaic squares of the Game of the Goose on the Plaza de Santiago and discover how each square is connected to a place on the Camino. Then sign up for a city walking tour that includes visits to underground urban bodegas (wine cellars).

Kick off the evening sampling mouth-watering pinchos and celebrated La Rioja wines in over 50 bars on the historic streets around Calle del Laurel.

For the next 5 kilometers (3.1 miles), Logroño’s industrial outskirts are unappealing; you can skip them by taking a bus to the hilltop town of Navarrete, where you can stamp your credential at Iglesia de la Asunción. Leaving Navarrete, take a small detour to the hamlet of Ventosa. On your way into town, stop at Bar Virgen Blanca for a snack or lunch and to try the local vintage.

Two kilometers (1.2 miles) after Ventosa, climb to breathtaking views of vines and the steep red cliffs of the Alto de San Antón. Next is a long and industrialized walk into Nájera, where you’ll be rewarded with tree-covered parks running along both banks of the refreshing Río Najerilla. Cross the bridge to enter the Monasterio de Santa María la Real, built into the red cliffs. Inside, the miraculous medieval statue of Mary is reached through a tunnel into the rock.

This is a fairly low-impact day. First, climb over Nájera’s ridge into more wheat fields and vineyards, past the pilgrim support villages of Azofra and Cirueña, the latter with a golf course right before entry. Continue to Santo Domingo and allow an hour to see the town’s cathedral, Santo Domingo de la Calzada, which contains the tomb of the great engineer saint, along with the living descendants of the miracle rooster-and-hen pair who, centuries ago, saved an innocent pilgrim’s life.

This is a long but reasonably level trail day. Leave Santo Domingo crossing the Rio Oja, which gives its name to the autonomous community of La Rioja, and gently climb to the corn, wheat, and herding community of Grañon. Pass more sweeping wheat fields and oak forest, where you cross from La Rioja into Castile and enter the village of Redecilla del Camino (11.2 km/7 mi after Santo Domingo), whose Iglesia de la Virgen de la Calle is noted for its finely carved Romanesque baptismal font of the celestial city of heaven and is worth a quick five-minute stop.

To break up the day into two, stop at Hostal El Chocolatero (which offers excellent pilgrim menus) in Castildelgado, 12.8 kilometers (8 miles) after Santo Domingo. Otherwise, press on for 22 more kilometers (13.7 miles) to Villafranca Montes de Oca, where you can stay in San Antón Abad, the restored 14th-century pilgrims’ hospital on the edge of a large native pine forest.

Before you leave, note that this first stretch of this day, from Villafranca Montes de Oca to San Juan de la Ortega, is a long 12.1 kilometers (7.5 miles) with no support services.

Climb the Camino directly out of Villafranca and into pine forest, to a 1,100-meter-high (3,609 feet) lookout point. Then descend into pine and fern forest and into the valley, where you will find one of the Camino’s great gems, the monastery and church of Iglesia de San Nicolás de Barí, in the town of San Juan de la Ortega. Take a half-hour to visit the church and enjoy the Zen-style meditation niche, and then stop for lunch at the cheery Bar Marcela.

Continue to Atapuerca, crossing a landscape that’s been inhabited by humans for up to 1.2 million years. Stay at Casa Rural Papasol, a French-style country inn, and splurge on dinner at the innovative nouveau Castilian cuisine restaurant, Comosapiens.

Leave Atapuerca before dawn so you can take in a beautiful sunrise on the Matagrande ridge of the Sierra de Atapuerca. This ridge is your last climb before a slow descent toward Burgos, passing into more urban development as you go. You have three choices for routes, the shortest being the least attractive, and the longest (the one along the river) the prettiest and most pleasant.

In the morning, arrange a bus trip from Burgos’s Human Evolution Museum to the Atapuerca Archaeological Site.

Alternatively, explore Burgos’s medieval town center. Visit the Gothic Catedral de Santa María, where El Cid is buried, and the surrounding churches and squares within the walled medieval town.

In the afternoon, climb up the hill behind the cathedral to Burgos’s castle, Castillo de Burgos, for stunning views of the city and countryside. Walk along the river Arga through the center of the city, stopping at the Cartuja de Miraflores and the royal Las Huelgas monasteries on the way.

End the day with tapas and pinchos on Plaza Mayor, followed by live music at Burgos’s 1921 literary café, Café España.

Follow the Camino west out of Burgos through the old city’s fortified wall at the medieval gate of San Martin. Ten kilometers (6.2 miles) outside Burgos, stop for a hearty egg sandwich at Tardajos village’s Café Bar Ruiz. A couple kilometers (a mile or so) later, in Rabé de las Calzadas, stop in for a stamp at the 13th-century Iglesia de Santa Marina.

Next up is the village of Hornillos del Camino, a Celtiberian town that has been welcoming pilgrims since the 12th century. Stop here to enjoy the fresh and flavorful menú del peregrino at the Bar Casa Manolo, and stay for the night. Alternatively, for a more rustic experience (no plumbing or electricity), continue another 5.7 kilometers (3.6 miles) further to Arroyo de Sanbol to slumber in a beehive-shaped albergue with unforgettable views of the Milky Way.

Rippling exposed hills, some rather steep, define this day. Leave Hornillos del Camino toward Arroyo de Sanbol, pausing to dip your feet in the healing spring a few meters south of the Camino. Then climb about 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) more toward Hontanas, from where you’ll descend about 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) to the isolated ruins of Monasterio de San Antón. Take a few moments to leave a note in the stone niche of the ruined monastery before continuing to the Celtiberian hilltop town of Castrojeriz.

In Castrojeriz, stop a few minutes in the Iglesia del Manzano at the town entrance to see the Camino’s second most miracle-working Mary, Nuestra Señora del Manzano, on the altar. Proceed through Castrojeriz toward the steepest climb of the day, and best views, to the Alto de Mostelares, then descend to the solitary Ermita de San Nicolás, 7.5 kilometers (4.7 miles) from Castrojeriz on the bank of the Pisuerga river. Stay here in the one-room medieval hermitage-turned-albergue that sleeps up to 12 in its chapel, with evening prayer, a good communal meal by candlelight, and views of the Milky Way. If it is full, continue 3.3 kilometer (2 miles) to the agreeable agricultural village of Itero de la Vega on the other side of the river.

You’ll press deeper into this wide-open country of the meseta. Entering Boadilla del Camino after 11.6 kilometers (7.2 miles), pause a moment at its square to see the ornate 15th-century pillar of justice, Rollo de Boarilla, where laws and sentences were issued, then continue 5.7 kilometers (3.5 miles) to the farming town of Frómista and take at least a half-hour to explore the Iglesia de San Martín, considered the purest French-style Romanesque church in Spain.

Continue on a straight, 14.2-kilometer (8.8-mile) path to Villalcázar de Sirga, a village centered around the immense red stone 13th-century Iglesia de Santa María la Blanca, which houses the most miraculous and celebrated Mary on the Camino. Stay at Hostal Las Cantigas and enjoy a medieval-style dinner in Mesón de los Templarios (a destination for people across the region), or press on 5.6 more kilometers (3.5 miles) to Carrión de los Condes and join the nuns for their evening sing-along and communal dinner at the Albergue de Santa María.

on trail on the meseta to Carrión de los Condes

If you’re walking during warm weather, get an early start to get some walking done before the hot afternoon. Otherwise, take a half-hour to visit the two medieval churches in Carrión de los Condes, and slow down to take in the immensity of the medieval monastery of San Zoilo, once the second most powerful in Castile.

Stock up with water and food for the day before leaving Carrion: There are no support services for the next 17 kilometers (10.6 miles). When you reach Calzadilla de la Cueza, pause at the village bar for refreshment and food. I don’t recommend staying here, though. Instead, continue 9.5 more kilometers (6 miles) to Terradillos de los Templarios, a Roman town connected to Templars in the Middle Ages. Stop here for the night at the Albergue Jacques de Molay. Alternatively, continue 3.2 more kilometers (2 miles) to Moratinos, where you can dine in an underground wine bodega at Castello de Moratinos and sleep at the basic, Italian-run Albergue San Bruno.

This short day of walking allows a half-day to explore Sahagún and pick up your halfway certificate. Leave Moratinos and in 2.6 kilometers (1.6 miles) enter the gregarious hamlet of San Nicolás del Camino Real, where you can pause for a good breakfast at the two excellent village cafés, Casa Barrunta and Albergue Laganares. Follow the dirt tract from there toward the Ermita de la Virgen del Puente, a Mudéjar (Islamic-style) hermitage dedicated to Mary.

From the hermitage, continue 2.4 kilometers (1.5 miles) to Sahagún, once the center of the most powerful monastery in Spain. Enjoy lunch and the vibrant social life on the Plaza Mayor. Pick up your halfway certificate at the Santuario de la Peregrina, one of several beautiful Mudéjar brickwork-and-stucco sacred sights that is worth taking an hour to see. Take another hour to walk around town and see the other Mudéjar churches of San Lorenzo and San Tirso.

Four kilometers (2.5 miles) after leaving Sahagún, the path forks. Take the left fork to stay on the historic Camino Real, which leads to the Ermita de Nuestra Señora de Perales, just before the village of Bercianos del Real Camino. Cheerful local caretakers at the hermitage enjoy greeting pilgrims and stamping credentials.

At 7.3 kilometers (4.5 miles) after Bercianos del Real Camino is the decent-sized village of El Burgo Ranero, which offers several choices for lodging. Play cards with locals at the bars of the side-by-side Hostal El Peregrino and Hostal Piedra Blanca, and enjoy an organic, local, and homemade dinner at La Costa del Adobe.

From El Burgo Ranero, it’s nearly 13 kilometers (8 miles) to the former Roman villa of Reliegos, which is today a pilgrim and farming town. Upon entering town, keep an eye out for bodegas, private family wine cellars built into the ground.

The town of Mansilla de las Mulas, 6.3 kilometers (3.9 miles) after Reliegos, is surrounded by 10-foot-thick walls built on Roman foundations. Pass into the walled center of the small town and meander along its many small squares. Visit the Museo Etnográfico Provincial de León, the town’s ethnographic museum highlighting regional cultures, especially the Maragatos, the traditional muleteers of León. Consider hiring a taxi with other pilgrims for an hour-long round-trip excursion (including the time to explore) from Mansilla de las Mulas to the 10th-century Visigothic and Mozarabic church of San Miguel de Escalada.

At 3.2 kilometers (2 miles) after Mansilla de la Mulas, a 1-kilometer (0.6-mile) detour to the right leads you to one of the best Roman remains on the Camino: The archaeological site of Lancía, which was occupied by Romans 2,000 years ago. Take 30 minutes to explore the site (visits are usually possible in the morning Mon.-Fri.).

The approach to León is through heavily industrialized urban terrain. To skip this long, unpleasant stretch, walk another 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) to the settlement of Puente Villarente, where you can catch the local bus into León.

Spend the morning exploring Spain’s purest and most French Gothic cathedral, Catedral de Santa María, with an astounding number of stained-glass windows; also see Spain’s best-preserved medieval frescoes in the royal pantheon of the Basilica de San Isidoro.

a traditional granary, horreo, in Galicia

Next, walk along the walls of the original Roman town, where you can still see the Roman walls enclosing the old city center. Pause for a glass of León’s best wines at Vinos Grifo on the city’s oldest and most atmospheric square, the Plaza del Grano.

In the evening, treat yourself to the luxury quarters of the restored medieval monastery Parador San Marcos, and join the locals for a tapas crawl in the Barrio Húmedo, where each venue prides itself in creating innovative little dishes to serve with your order of wine or beer.

The stretch leaving León is almost as ugly as the stretch entering the city. Fortunately, it’s easy to catch a bus to the shrine of La Virgen del Camino, 7.7 kilometers (4.8 miles) away. Spend a half-hour taking in the living mysticism of this modern but appealing temple dedicated to the vision and presence of Mary. Then refresh yourself with a good egg sandwich, orange juice, and coffee at the bar across the street, El Peregrino.

From here, the Camino resumes on flat terrain. In 17.7 kilometers (11 miles), you’ll reach one of the most welcoming albergues on the Camino, La Vieira in San Martín del Camino, where you can get a bed for the night and a generous communal dinner made with produce from the owner’s daughter’s farm.

This is your last full day on the meseta. Around 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) after leaving San Martín del Camino, you arrive at the Puente del Paso Honroso, the medieval 19-arched bridge that’s known for a legendary jousting tournament. Cross it, then walk through the village of Hospital de Órbigo.

Passing through a few other villages, you’ll enter Astorga, one of Roman Spain’s most important cities, through its high Roman walls. Dig into the town’s Roman roots at the Museo Romano, from where you can also depart for an hour-long archaeological walking tour of the town. Follow up with a half-hour in local chocolate history, with samples, at the Museo de Chocolate. Finally, spend an hour taking in taking in the sacred art in the 15th-century Catedral de Santa María and the Museo de Catedral.

Today you leave the meseta and enter León’s mountains. As you depart Astorga, pause at the restful and poignant pilgrim memorial garden at Ermita de Ecce Homo hermitage, then continue toward the traditional Maragato village of Castrillo de los Polvazares. (If you have the time, stopping for a day or more at the powerful and creative sacred art retreat of Flores del Camino is strongly recommended.)

a falcon in León

Continue to El Ganso, 13 kilometers (8 miles) from your starting point in Astorga, and pause for refreshment at the Mesón Cowboy, a Wild-West-themed bar. Then continue along increasingly rocky terrain into the gateway of the mountains at Rabanal del Camino. Eat and sleep at the rural B&B, The Stone Boat, and conclude the evening with chanted Gregorian prayer led by the Benedictines in Rabanal’s Iglesia de la Asunción daily at 7pm and 9pm.

Today you will climb deeply and, at times, steeply into Leon’s mountains along a rugged trail toward Foncebadón (5.5 km/3.4 mi after Rabanal del Camino), a perfect place to rest and refuel before climbing the last few kilometers to the Camino’s highest altitude point: the Cruz de Ferro on Monte Irago. When you arrive at Cruz de Ferro, you have the chance to perform the Camino’s most potent ritual, leaving a stone at the base of the towering iron-and-oak cross.

Next, continue to the modern Templar hamlet of Manjarín, where you can stop for a stamp from modern-day Templar Knight, Tomás Martinez de la Paz, before continuing to the pretty stone villages of El Acebo and Riego de Ambros. A final stretch of gorgeous alpine terrain leads into the refreshing riverside town of Molinaseca, where you leave the mountains behind and enter the fertile garden valley of El Bierzo. Stop at El Capricho de Josana for a room and a passionately prepared meal with El Bierzo and Italian flourishes. Alternately, continue to Ponferrada and stay in La Virgen de la Encina hostal, joining the evening tapas and dinner scene at Taberna La Obrera.

From Molinaseca, it is an easy 8-kilometer (5-mile) walk to Ponferrada. Allow 1-2 hours to explore the town’s attractions: Castillo de los Templarios, the large Templar castle on the riverbank; Basilica de Nuestra Señora de la Encina, a church with pagan and possibly Templar roots, and the extraordinary 10th-century pre-Romanesque church, Santo Tomás de las Ollas, a 1-kilometer (0.6-mile) detour north of the town center.

After your sightseeing, stop for refreshment or lunch at Ponferrada’s Bar Virgen de la Encina. Then cross the Sil river and pass several medieval hamlets, with olive groves and apple and pear orchards, on the way to Cacabelos, where you enter an important wine region since Roman times.

As you leave Cacabelos you enter the hamlet of Pieros, and the edge of a Celtic castro that defines the original settlement. Continue through the gorgeous, vineyard-covered hills that produce the unique El Bierzo wines.

Arrive in Villafranca del Bierzo (8.5 km/5.3 mi from where you started in Cacabelos) in time for lunch on the Plaza Mayor (Restaurante Compostela is a favorite). But first, pause at the town’s most iconic monument, Iglesia de Santiago with its ornate Puerta del Perdón (gate of pardon), where medieval pilgrims who not could make it to Santiago de Compostela sought pardon. (It’s rarely open, but touch the door for luck nevertheless!)

Continue across the river and deeper into the mountain pass toward Pereje, and then the Valcarce river and valley toward Trabadelo. One kilometer (0.6 miles) before Trabadelo, slow down and savor the ancient chestnut forest whose branches arch overhead like a natural cathedral canopy. Stay in Trabadelo at Hostal-Albergue Crispeta and dine in the establishment’s bar-restaurant. (Ask for the homemade quince jam to pair with a dessert of local cheese or the homemade yogurt-like custard, cuajada.)

Santuario da Virxe da Barca in Muxía

Pass more deeply into the green, narrow mountain terrain, through the heart of several tiny river-valley hamlets with pretty gray granite chapels that offer good food, drink, and rest. As you pass through Ambasmestas, 5.3 kilometers (3.3 miles) after Trabadelo, duck into Quesería Veigadarte to purchase some local goat cheese for a trailside picnic lunch. (It goes great with apples and fresh bread.) Consider setting aside an hour to climb to the 9th-century castle, Castillo de Sarracín, from the village of Vega de Valcarce, and pause in the next village of Ruitelan to refresh and refuel at Bar Omega or the climb ahead.

Las Herrerías is the last valley settlement before the ascent to O Cebreiro, the third-highest peak on the Camino. Take it slow, and pace yourself on the sheer incline. At the mountain-hugging village of La Faba, you can rest at the enjoyable village café, and then push up into the final ascent.

When you arrive at O Cebrerio, wander the small village, taking in its traditional round stone- and thatch-roofed pallozas. Pause at Mesón Antón for a drink to watch the sunset, or attend evening pilgrims’ mass in the Iglesia de Santa María.

Take in the sunrise over the eastern mountains before leaving O Cebreiro. From here, the terrain gets greener and greener as it weaves in and out of several mountain villages that offer food, drink, and lodging. Good places to stop for a bite are the high lookout point of Alto do Poio, 8.7 kilometers (5.4 miles) after O Cebreiro, where the Bar Puerto serves a tasty caldo Gallego, or Fonfría, 3.4 kilometers (2.1 miles) later, with an albergue bar and a lady who sells crepes in front of her village house.

Next, descend deeply into the rich river valley and village of Triacastela, where you can stay in two joined refurbished farmhouses at Albergue Atrio, attend an inspiring early evening pilgrims’ mass in the 12th-century church, Iglesia de Santiago, and enjoy good pilgrim’s fare at Restaurante Complexo Xacobeo.

You have two choices to get to Sarria. Either detour to the Benedictine Monasterio de Samos (which will add 6.4 km/4 mi to your trek), where you can stay and attend a monastic retreat, or continue on the more traditional Camino, where you will pass through exquisite old chestnut woods and several villages with tiny chapels that offer support. The paths rejoin in Aguiada and near Sarria.

Sarria is not terribly pretty, but is very welcoming and has all the amenities. Its 13th-century Iglesia de San Salvador has an appealingly primitive engraving of Christ over the entrance, which is worth pausing to see. Stay in the Pensión or Albergue Don Álvaro where you can enjoy an after-dinner homemade orujo, eau de vie, with fellow pilgrims after taking a delicious Italian dinner at Matias Locanda Italiana.

Leaving Sarria, you’ll pass its castle ruins and cross the medieval Ponte Áspera over the Celeiro river, traversing ancient oak forest until you reach the village of Barbadelo, 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) away. Here, be sure to take the 50-meter (164-foot) detour to the left to see the Iglesia de Santiago, with its unusual and primitive engravings of Christ. Continue to Ferreiros and its tiny but expressive Romanesque Iglesia de Santa María.

Climb to the plateau overlooking Portomarín’s river valley, then descend, crossing the river at the high, vertigo-inducing modern bridge into Portomarín. Take half an hour to visit Portomarín’s two Romanesque churches, San Nicolás and San Pedro. Then enjoy a good meal along the central arcaded passageways in the town center (a favorite is Posada del Camino, seated on the terrace overlooking Iglesia de San Nicolás).

Leave Portomarín, crossing a small tributary of the Belesar dam. Pass through oak and chestnut forest on the climb to the farm village of Gonzar (7.8 km/4.8 mi from Portomarín), where you can rest on the outdoor terrace at Casa García. Continue a couple more kilometers (a little over a mile) to Castromaior, a small village with an excellent bar making homemade treats, including fresh yogurt.

Allow a half-hour to take the 200-meter (656-foot) detour left off the Camino after Castromairo to the 2,400-year-old castro site of Castro de Castromaior. Follow the path from there through fields and forest to the deeply symbolic Cruceiro de Lameiros near Ligonde, another pretty farming village. Finally, stop for the night in Eirexe at the cozy Pensión Eirexe, taking a pilgrim’s dinner across the street at the cheerful village restaurant, Restaurante Ligonde.

From Eirexe, the Camino meanders 7.6 kilometers (4.7 miles) to Palas de Rei, a serious working farm town centered on the Iglesia de San Tirso. From here, continue to San Xulián do Camino with its well-preserved 12th-century Romanesque church. After several other hamlets, enter Leboreiro, whose village church, Iglesia de Santa María, is dedicated to Mary, who is said to have appeared in a nearby fountain one night, combing her hair. Take a few moments to study the church entrance, an unusual tympanum of appealingly primitive design.

On your way to Melide (5.7 km/3.5 mi from Leboreiro), you’ll cross over two pretty stone medieval bridges, in Leboreiro and in Furelos. Melide is where you can get your first best taste of Galicia’s famous dish, pulpo á feria, paprika-spiced octopus. To sample the dish, you have your pick of three excellent places.

One kilometer (0.6 miles) from the center of Melide, pause for perhaps 15-30 minutes at a crown jewel of the Camino: the Iglesia de Santa Maria de Melide, a 12th-century church with expressive animal sculptures and well-preserved frescoes, all overseen by a modern-day Templar knight. Then follow the tree-covered lanes and forest paths to the 13th-century bridge that leads into Ribadiso da Baixo, a hamlet of nine people where they are restoring the medieval pilgrims’ Hospital de San Antón.

Continue along country roads and a slight ascent until you reach the substantial town of Arzúa, an upbeat place famous for locally produced cow’s milk cheeses (and a great place to try them). Stay the night in the family-run Pensión Casa Frade, and dine at Restaurante Casa Nene, where the dessert cheese plate will let you sample the best of Arzua’s cheeses.

From Arzúa, the Camino continues through bucolic countryside and tiny settlements. Make a point of being in O Empalme (15.3 km/9.5 mi from Arzúa) in time for lunch at O Ceadoiro, a delightful roadside café with locally harvested and home-cooked meals popular with locals.

A kilometer (half a mile) after O Empalme, pass through the hamlet of Santa Irene and soon after a short detour leads to an array of food and accommodations options in O Pedrouzo. Alternately, continue straight on to the hamlet of Amenal where the only show in town is the Hotel Amenal, an excellent option for accommodations, drinks, and dinner.

Your last day starts in fragrant eucalyptus forest and proceeds to the historic village of Lavacolla (10 km/6.2 mi after O Pedrouzo, and 6.6 km/4.1 mi after Amenal), where you will pass over the village stream where medieval pilgrims washed themselves in preparation for arriving in Santiago. Continue through a neighborhood on the outskirts of Santiago and climb toward Monte del Gozo, the traditional spot where medieval pilgrims first saw the spires of Santiago de Compostela’s cathedral. The tree cover now hides the view, so you’ll have to wait another kilometer to see the spires (but you can still jump for joy here anyway).

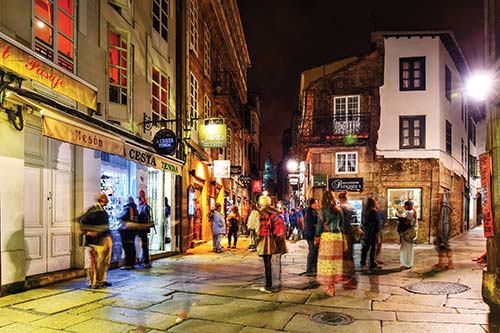

nighttime in Santiago de Compostela

Follow the descending path along the side of the road and into the neighborhood of San Lázaro, where way-markers along the streets lead you into the medieval center of the city and straight to the cathedral square, Plaza de Obradoiro, which faces the western entrance of the cathedral, Catedral de Santiago de Compostela, where Saint James is said to be entombed. Do as pilgrims have done over the past millennia: Enter the cathedral and deliver a long-awaited hug to Santiago on the high altar. Congratulations! You did it!

If you did not yet do it, head first to the cathedral to hug Santiago on the high altar and soak in the splendor of the Romanesque church, then head to the pilgrims’ reception office to receive your Compostela.

Stop for a celebratory lunch at Casa Manolo (near the cathedral), or purchase picnic foods at the vibrant daily market Mercado de Abastos. After lunch, spend an hour in the pilgrimage museum, Museo de Peregrinaciones, then spend another hour walking to the outer edge of the old town to see either the surviving 3,000-year-old petroglyph, Castriño de Conxo, or the Romanesque Iglesia del Sar.

Return to the cathedral for evening pilgrims’ mass at 7:30pm daily. (If you’re lucky, you will get to see the massive incense burner, botafumeiro, in use.) Then kick off the evening sampling the tapas, pinchos, and regional wines at the bars lining on the streets of Rúas Franco, Nova, Vilar, and Raiña. Finish the evening at Costa Vella’s starry garden café or over a flaming cup of queimada at Cafe Casino.

Prepare for a day of constant up-and-down climbing, some of it fairly steep. Leave Santiago de Compostela via pleasant city streets and forest paths into green countryside. Arrive in Pontemaceira (17 kilometers/10.6 miles from Santiago de Compostela) and pause at the Restaurante Ponte Maceira for a late lunch. In 4 more kilometers (2.5 miles), cross the medieval bridge to Negreira, an agreeable small town with stately pazos (country mansions), along with several options to eat and sleep well.

Continue through rural green terrain, dotted with distinctive Galician horreos (traditional granaries mounted on stone stilts), that rises and falls less dramatically than yesterday’s section. Options for food and drink are hit or miss, so stock up before leaving Negreira. In the tiny village of Santa Mariña, the upbeat Albergue Casa Pepa offers good lodging in a traditional country home as well as delicious dinners. Alternately, you can press on for 11.9 kilometers (7.4 miles) to Olveiroa, a similarly sized village with options for accommodations and food.

Get an early start and continue for 17 kilometers (10.6 miles) on a gentle ascent through Olveiroa, Logoso, and Hospital. Be sure to stock up on food and water in one of these villages; there is no support on the final 14.4-kilometer (9-mile) stretch from Hospital to Cee. After Hospital, the trail forks; go left for Finisterre. The trail here is a dirt path through verdant forests and fields. It passes a regionally celebrated shrine, Capela de Nosa Señora das Neves, that’s worth a few minutes’ pause to see the sculpture of the chapel’s namesake in the covered porch outside; it’s also worth it to stop at the traditional healing well.

Soon after you leave the chapel you will catch your first glimpse of the bay and ocean beyond. The trail then descends steeply to the picturesque fishing towns of Cee and Corcubión. Both have ample options for food and accommodations. Be sure to take a few minutes in Cee to visit the Iglesia de Santa Maria de Xunquiera, and in Corcubión to visit the Iglesia de San Marcos.

From Cee and Corcubión, the trail follows along the rocky coast to the sweeping sandy beach of Praia da Langosteira, less than 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) before Finisterre. Stop at this beach to join other pilgrims in a ritual dive into the ocean, and search for a scallop shell to take home.

When you reach Finisterre, make the final climb to kilometer 0 at the “Earth’s end,” the tip of land where the lighthouse stands at Cabo Finisterre. Take the road from the lighthouse up to the top of Monte Facho to see the Piedras Sagradas (sacred stones), then follow the branching trail to the hermitage of Ermita de San Guillerme. Both are possible locations of the ancient Ara Solis, pagan sun altar.

Watching the sunset from Cabo Finisterre is an ancient pilgrim’s ritual. To view it, some pilgrims like to return to the lighthouse and carefully climb to the rocks below its base, take a seat, and dangle their feet over the edge tumbling down to the waves.

This trek along the coast, deep in maritime hills and river valleys, may be the prettiest and wildest of all the stretches of the Camino. The only village offering food and accommodations is midway at Lires, 13.6 kilometers (8.5 miles) north of Finisterre. In 9.1 kilometers (5.7 miles) after Lires, the climb to Monte Facho de Lourido (269 m/883 ft) is the steepest on this route.

As you near Muxía, take in views of the sparkling blue ocean and massive stones that make up the coast. A festive meal of crisp local white wine and grilled scallops or steamed gooseneck barnacles is in order at Bar A Marina on the harbor. Before sunset, walk the 900 meters (0.6 mile) from the settlement to Muxía’s seaside church at the village’s tip of land, the Santuario da Virxe da Barca, and settle in along the large polished rocks to watch the sunset over the ocean.

Two direct buses from Muxía (one in the morning and one in the afternoon) will get you back to Santiago de Compostela (1.5 hours), your nearest transportation hub from which to make train, bus, or flight connections to return home.