Shutterstock

Demilitarized Zone

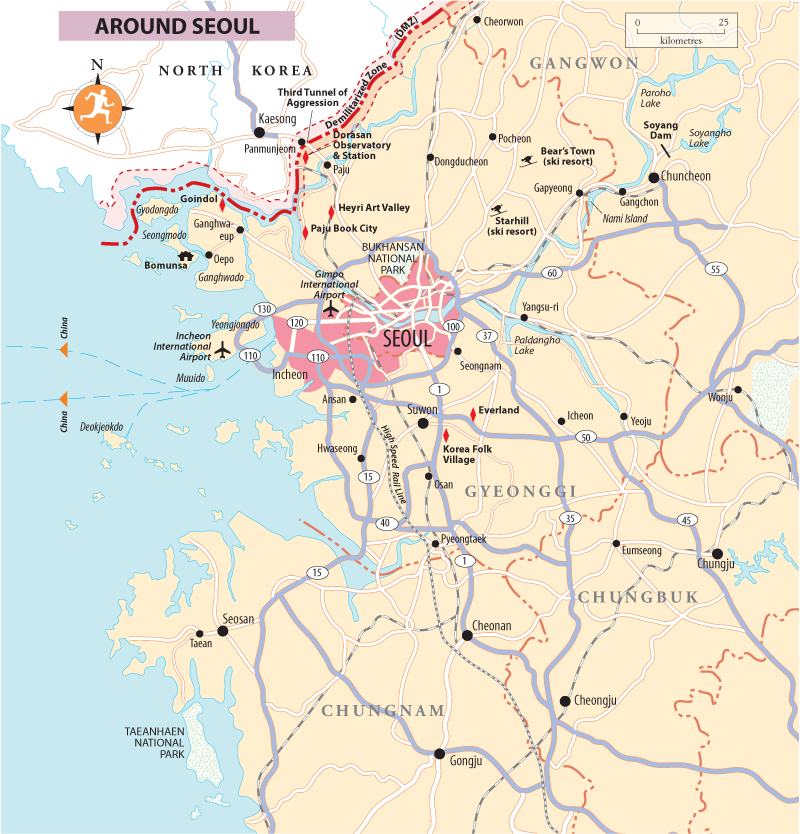

There’s no reason for your trip to begin and end with the city centre, since there’s a wonderful array of sights within easy day-tripping range of the capital. Most popular is a visit to the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) separating North and South Korea, a 4km-wide buffer zone often described as one of the most dangerous places on Earth. It’s even possible to step across the border here, in the infamous Joint Security Area. The DMZ forms the northern boundary of Gyeonggi (경기), a province that encircles Seoul. This is one of the world’s most densely populated areas – including the capital, over 25 million people live here.

Most cities here are commuter-filled nonentities, but a couple are worthy of a visit. Incheon, to the west of Seoul, was the first city in the country to be opened up to international trade, and remains Korea’s most important link with the outside world thanks to its hub airport and ferry terminals. It sits on the shores of the West Sea, which contains myriad tranquil islands. Heading south of Seoul you come to Suwon, home to a renowned fortress, and useful as a springboard to several nearby sights. Further south again is the small city of Gongju, now a sleepy place but once capital of the famed Baekje dynasty.

As you head slowly north out of Seoul through the traffic, the seemingly endless urban jungle gradually diminishes in size before disappearing altogether. You’re now well on the way to a place where the mists of the Cold War still linger, and one that could well have been ground zero for the Third World War – the Demilitarized Zone. More commonly referred to as “the DMZ”, this no man’s land is a 4km-wide buffer zone that came into being at the end of the Korean War in 1953. It sketches an unbroken spiky line across the peninsula from coast to coast, separating the two Koreas and their diametrically opposed ideologies. Although it sounds forbidding, it’s actually possible to enter this zone, and take a few tentative steps into North Korean territory – thousands of civilians do so every month, though only as part of a tightly controlled tour. Elsewhere are a few platforms from which the curious can stare across the border, and a tunnel built by the North, which you can enter.

The Axe Murder Incident and Operation Paul Bunyan

Relations between the two Koreas took a sharp nose dive in 1976, when two American soldiers were killed by a group of axe-wielding North Koreans. The cause of the trouble was a poplar tree which was next to the Bridge of No Return: a UNC outpost stood next to the bridge, but its direct line of sight to the next Allied checkpoint was blocked by the leaves of the tree, so on August 18 a five-man American detail was dispatched to perform some trimming. Although the mission had apparently been agreed in advance with the North, sixteen soldiers from the KPA turned up and demanded that the trimming stop. Met with refusal, they launched a swift attack on the UNC troops using the axes the team had been using to prune the tree. The attack lasted less than a minute, but claimed the life of First Lieutenant Mark Barrett, as well as Captain Bonifas (who was apparently killed instantly with a single karate chop to the neck). North Korea denied responsibility for the incident, claiming that the initial attack had come from the Americans.

Three days later, the US launched Operation Paul Bunyan, a show of force that must go down as the largest tree-trimming exercise in history. A convoy of 24 UNC vehicles streamed towards the plant, carrying more than 800 men, some trained in taekwondo, and all armed to the teeth. These were backed up by attack helicopters, fighter planes and B-52 bombers, while an aircraft carrier had also been stationed just off the Korean shore. This carefully managed operation drew no response from the KPA, and the tree was successfully cut down.

For the first year of the Korean War (1950–53), the tide of control yo-yoed back and forth across the peninsula. Then in June 1951, General Ridgeway of the United Nations Command (UNC) got word that the Korean People’s Army (KPA) would “not be averse to” armistice talks. These took place in the city of Kaesong, now a major North Korean city, but were soon shifted south to Panmunjeom, a tiny farming village that suddenly found itself the subject of international attention.

Cease-fire talks went on for two long years and often degenerated into venomous verbal battles littered with expletives. One of the most contentious issues was the repatriation of prisoners of war, and a breakthrough came in April 1953, when terms were agreed; exchanges took place on a bridge over the River Sachon, now referred to as the Bridge of No Return. “Operation Little Switch” came first, seeing the transfer of sick and injured prisoners (notably, six thousand returned to the North, while only a tenth of that number walked the other way); “Operation Big Switch” took place shortly afterwards, when the soldiers on both sides were asked to make a final choice on their preferred destination. Though no peace treaty was ever signed, representatives of the KPA, the UNC and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army put their names to an armistice on July 27, 1953; South Korean delegates refused to do so.

An uneasy truce has prevailed since the end of the war – the longest military deadlock in history – but there have been regular spats along the way. In the early 1960s a small number of disaffected American soldiers defected to the North, after somehow managing to make it across the DMZ alive, while in 1968 the crew of the captured USS Pueblo walked south over the Bridge of No Return after protracted negotiations. The most serious confrontation took place in 1976, when two American soldiers were killed in the Axe Murder Incident, and in 1984, a young tour leader from the Soviet Union fled from North Korea across the border, triggering a short gun battle that left three soldiers dead. Even now, most years still see at least a couple of incidents – in late 2017, for example, a North Korean soldier defected across the DMZ, with CCTV footage of his flight going viral.

“The visit to the Joint Security Area at Panmunjeom will entail entry into a hostile area, and possible injury or death as a direct result of enemy action”

Disclaimer from form issued to visitors by United Nations Command

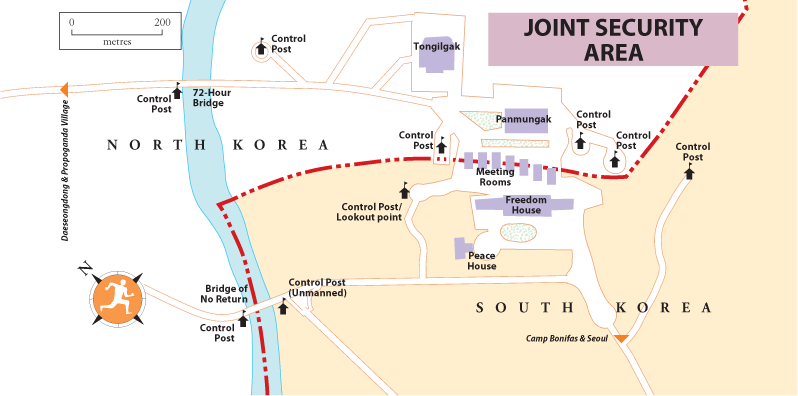

There’s nowhere in the world quite like the Joint Security Area (“the JSA”), a settlement squatting in the middle of Earth’s most heavily fortified frontier, and the only place in DMZ territory where visitors are permitted. Visits here will create a curious dichotomy of feelings: on the one hand, you’ll be in what was once memorably described by Bill Clinton as “the scariest place on Earth”, but on the other hand as well as soldiers, barbed wire and brutalist buildings you’ll see trees, hear birdsong and smell fresh air. The only way to get into the JSA is on a guided tour, which takes you to the village of Panmunjeom (판문점) in jointly held territory – though this has dwindled to almost nothing since it hosted the armistice talks in 1951.

Once inside the JSA, you’ll see seven buildings at the centre of the complex, three of which are meeting rooms. If you are lucky, you’ll be allowed to enter one of these to earn some serious travel kudos – the chance to step into North Korea. The official Line of Control runs through the centre of these cabins, the corners of which are guarded by South Korean soldiers, who are sometimes joined by their Northern counterparts, the enemies almost eyeball to eyeball. Note the microphones on the table inside the room – anything you say can be picked up by North Korean personnel. The rooms are closed to visitors when meetings are scheduled.

From a lookout point outside the cabins you can soak up views of the North, including the huge flag and shell-like buildings of Propaganda Village. You may also be able to make out the jamming towers it uses to keep out unwanted imperialist signals – check the reception on your phone. Closer to the lookout point, within JSA territory, the Bridge of No Return was the venue for POW exchange at the end of the Korean War, and also for James Bond in Die Another Day – though for obvious reasons it was filmed elsewhere.

Daeseongdong and “Propaganda Village”

The DMZ is home to two small settlements, one on each side of the Line of Control. With the southern village rich and tidy and its northern counterpart empty and sinister, both can be viewed as a microcosm of the countries they belong to.

The southern village – Daeseongdong (대성동) – is a small farming community, but one off-limits to all but those living or working here. These are among the richest farmers in Korea: they pay no rent or tax, and DMZ produce fetches big bucks at markets around the country. Technically, residents have to spend 240 days of the year at home, but most commute here from their condos in Seoul to “punch in”, and get hired hands to do the dirty work; if they’re staying, they must be back in town by nightfall, and have their doors and windows locked and bolted by midnight. Women are allowed to marry into this tight society, but men are not; those who choose to raise their children here also benefit from a school that at the last count had twelve teachers, and only eight students.

North of the line of control is Kijongdong (기정동), an odd collection of empty buildings referred to by American soldiers as “Propaganda Village”. The purpose of its creation appears to have been to show citizens in the South the communist paradise that they’re missing – a few dozen “villagers” arrive every morning by bus, spend the day taking part in wholesome activities and letting their children play games, then leave again in the evening. With the aid of binoculars, you’ll be able to see that none of the buildings actually has any windows; lights turned on in the evening also seem to suggest that they’re devoid of floors. Above the village flies a huge North Korean flag, so large that it required a fifty-man detail to hoist, until the recent installation of a motor. It sits atop a 160m-high flagpole, the world’s tallest, and the eventual victor in a bizarre contest between the two Koreas, each hell-bent on having the loftier flag.

INFORMATION THE JOINT SECURITY AREA

Note that each tour comes with a number of restrictions, most imposed by the United Nations Command. Be warned that schedules can change in an instant, and remember that you’ll be entering an extremely dangerous area – this is no place for fooling around or wandering off by yourself.

Paperwork For all tours to the DMZ you’ll need to bring your passport along. Citizens of certain countries are not allowed into DMZ territory, including those from most nations in the Middle East, some in Africa, and communist territories such as Vietnam, Hong Kong and mainland China.

Dress code An official dress code applies (no flip-flops, ripped jeans, “clothing deemed faddish” or “shorts that expose the buttocks”), but in reality most things are OK.

Photography In certain areas photography is not allowed – you’ll be told when to put your camera away.

Almost all tours to the DMZ start and finish in Seoul, and there are a great number of outfits competing for your money. We’ve listed a couple of recommended operators here, but you’ll find pamphlets from other operators in your hotel lobby; most speak enough English to accept reservations by telephone. Note that some operators are much cheaper than others – these probably won’t be heading to the JSA, the most interesting place in the DMZ (W70,000–80,000 with most operators), so do check to see if it’s on the schedule. Most tours also include lunch.

Panmunjom Travel Center ![]() 02 771 5593,

02 771 5593, ![]() koreadmztour.com. Offers the regular tour, plus a session with a North Korean defector willing to answer questions about life on the other side (W85,000). Runs from Koreana Hotel, near Myeongdong subway (line 4; see map).

koreadmztour.com. Offers the regular tour, plus a session with a North Korean defector willing to answer questions about life on the other side (W85,000). Runs from Koreana Hotel, near Myeongdong subway (line 4; see map).

USO

USO ![]() 02 6383 2570,

02 6383 2570, ![]() koridoor.co.kr. Run in conjunction with the American military, these are still the best tours to go for ($92), and include a 20min presentation by a US soldier in Camp Bonifas. Book at least four days in advance. Runs from Camp Kim, near Namyeong subway (line 1; see map).

koridoor.co.kr. Run in conjunction with the American military, these are still the best tours to go for ($92), and include a 20min presentation by a US soldier in Camp Bonifas. Book at least four days in advance. Runs from Camp Kim, near Namyeong subway (line 1; see map).

제3땅굴 • Only accessible as part of a tour

A short drive south of Panmunjeom, the Third Tunnel of Aggression is one of four tunnels dug under the DMZ by North Korean soldiers in apparent preparation for an invasion of the South. North Korea has denied responsibility, claiming them to be coal mines (though they are strangely devoid of coal), but to be on the safe side the border area is now monitored from coast to coast by soldiers equipped with drills and sensors. The tunnel was discovered in 1974 by a South Korean army patrol unit; tip-offs from North Korean defectors and some strategic drilling soon led to the discovery of another two tunnels, and a fourth was found in 1990. The third tunnel is the closest to Seoul, which would have been just a day’s march away if the North’s invasion plan had succeeded.

Many visitors emerge from the depths underwhelmed – it is, after all, only a tunnel, even if you get to walk under DMZ territory up to the Line of Control that marks the actual border. On busy days it can become uncomfortably crowded – not a place for the claustrophobic.

도라전망대 • Observatory Tues–Sun 10am–3pm • Free • Best accessed on the “DMZ Train” from Yongsan or Seoul station (Tues–Sun, departs Yongsan 10.08am and Seoul station 10.13am, returns from Dorasan 4pm; W9200 one-way)

South of the Third Tunnel is Dorasan observatory, from where visitors can stare at the North through binoculars. The observatory is included on many DMZ tours, but unlike the JSA you can also visit independently.

The gleaming, modern Dorasan station was built in early 2007 at the end of the Gyeonghui light-rail line. The line continues to China, via Pyongyang: as one sign says, “it’s not the last station from the South, but the first station toward the North”. In May 2007, the first train in decades rumbled up the track to Kaesong in North Korea (another went in the opposite direction on the east-coast line), while regular freight services started in December. Such connections were soon cut, but there remains hope that this track will one day handle high-speed services from Seoul to Pyongyang; in the meantime, a map on the wall shows which parts of the world Seoul will be connected to should the line ever see regular service, and there’s a much-photographed sign pointing to Pyongyang.

파주

The Seoul satellite city of PAJU contains some of the most interesting sights in the border area and, for once, they do not revolve solely around North Korea. The Paju Book City is a publisher-heavy area more notable for its architecture than anything literary, while the Heyri Art Valley is a twee little artistic commune.

파주 출판도시 문화재단 • ![]() pajubookcity.org • Bus #200 (every 30min; 1hr) from Hapjeong subway (lines 2 & 6)

pajubookcity.org • Bus #200 (every 30min; 1hr) from Hapjeong subway (lines 2 & 6)

Quirky Paju Book City is ostensibly a publishing district. Many publishers were encouraged to move here from central Seoul (though a whole glut of smaller printing houses remain in the fascinating alleyways around Euljiro) and most of the major companies based here have bookstores on their ground levels. However, the main attraction for visitors is the area’s excellent modern architecture – quite a rarity in this land of the sterile high-rise. There’s no focus as such, but strolling around the quiet streets dotted with great little book cafés is enjoyable.

헤이리 문화예술마을 • ![]() heyri.net • Bus #200 (every 30min; 45min) from Hapjeong subway (lines 2 & 6)

heyri.net • Bus #200 (every 30min; 45min) from Hapjeong subway (lines 2 & 6)

Seven kilometres to the north of Paju Book City, similar architectural delights are on offer at Heyri Art Valley. This artists’ village is home to dozens of small galleries, and its countryside air makes it an increasingly popular day-trip for young, arty Seoulites. They come here to shop for paintings or quirky souvenirs, or to sip a latte in one of the complex’s several cafés. However, such mass-market appeal means that the atmosphere here in general is more twee than edgy.

인천

Almost every international visitor to Seoul passes through INCHEON, Korea’s third most populous city. It’s home to the country’s main airport and receives all Korea’s ferries from China, though most new arrivals head straight on to Seoul as soon as they arrive. However, in view of its colourful recent history, it’s worth at least a day-trip from the capital. This was where Korea’s “Hermit Kingdom” finally crawled out of self-imposed isolation in the late nineteenth century and opened itself up to international trade, spurred on by the Japanese following similar events in their own country (the “Meiji Restoration”). Incheon was also the landing site for Douglas MacArthur and his troops in a manoeuvre that turned the tide of the Korean War.

Incheon’s most interesting district is Jung-gu, home to Korea’s only official Chinatown and Jayu Park, where a statue of MacArthur gazes out over the sea. Downhill from here, you can visit a couple of former Japanese banks in a quiet but cosmopolitan part of town, where many Japanese lived during the colonial era. Lastly, Incheon is also a jumping-off point for ferries to a number of islands in the West Sea.

중구 • Incheon subway (line 1)

Jung-gu district lies on the western fringe of Incheon, though it forms the centre of the city’s tourist appeal. On exiting the gate at Incheon station, you’ll immediately be confronted by the city’s gentrified Chinatown. Demarcated by the requisite oriental gate, it’s a pleasant and surprisingly quiet area to walk around with a belly full of Chinese food.

자유 공원 • 24hr • Free

Within easy walking distance of the subway station, Jayu Park is most notable for its statue of General Douglas MacArthur, staring proudly out over the seas that he conquered during the Korean War. Also in the park, the Korean–American Centennial Monument is made up of eight black triangular shards that stretch up towards each other but never quite touch – feel free to make your own comparisons with the relationship between the two countries. Views from certain parts of the park expose Incheon’s port, a colourful maze of cranes and container ships that provide a vivid reminder of the city’s trade links with its neighbours across the seas.

General MacArthur and the Incheon landings

“We drew up a list of every natural and geographic handicap… Incheon had ’em all.”

Commander Arlie G. Capps

On the morning of September 15, 1950, the most daring move of the Korean War was made, an event that was to alter the course of the conflict entirely, and is now seen as one of the greatest military manoeuvres in history. At this point the Allied forces had been pushed by the North Korean People’s Army into a small corner of the peninsula around Busan, but General Douglas MacArthur was convinced that a single decisive movement behind enemy lines could be enough to turn the tide.

MacArthur wanted to attempt an amphibious landing on the Incheon coast, but his plan was greeted with scepticism by many of his colleagues – both the South Korean and American armies were severely under-equipped, Incheon was heavily fortified, and its natural island-peppered defences and fast tides made it an even more dangerous choice.

However, the plan went ahead and the Allied forces performed successful landings at three Incheon beaches, during which time North Korean forces were shelled heavily to quell any counterattacks. The city was taken with relative ease, the People’s Army having not anticipated an attack on this scale in this area, reasoning that if one were to happen, it would take place at a more sensible location further down the coast. MacArthur had correctly deduced that a poor movement of supplies was his enemy’s Achilles heel – landing behind enemy lines gave Allied forces a chance to cut the supply line to KPA forces further south, and Seoul was duly retaken on September 25.

Despite the Incheon victory and its consequences, MacArthur is not viewed by Koreans – or, indeed, the world in general – in an entirely positive light, feelings exacerbated by the continued American military presence in the country. While many in Korea venerate the General as a hero, repeated demonstrations have called for the tearing down of his statue in Jayu Park, denouncing him as a “war criminal who massacred civilians during the Korean War”, and whose statue “greatly injures the dignity of the Korean people”. Documents obtained after his eventual dismissal from the Army suggest that he would even have been willing to bring nuclear weapons into play – on December 24, 1950, he requested the shipment of 38 atomic bombs to Korea, intending to string them “across the neck of Manchuria”. Douglas MacArthur remains a controversial character, even in death.

역사문화의 거리

The city has tried to evoke its colonial past on the Street of Culture and History by adding new wooden colonial-style facades to the street’s buildings. The effect is slightly bizarre, though the buildings do, indeed, look decidedly pretty. Most of the businesses that received a facelift were simple shops such as confectioners, laundries and electrical stores; many are still going, though they are now augmented by bars, arty cafés and the like.

Sinpo-ro 23-gil • Both daily 9am–5.30pm • W500 each

One block south of the odd Street of Culture and History is a road more genuinely cultural and historic. Here you’ll find a few distinctive Japanese colonial buildings which are surprisingly Western in appearance (that being the Japanese architectural fashion of the time). Three of the buildings were originally banks, of which two have now been turned into small museums. The former 58th Bank of Japan offers interesting photo and video displays of life in colonial times, while the former 1st Bank down the road has a less interesting display of documents, flags and the like. Sitting in a small outdoor display area between the two are some fascinating pictures taken here in the 1890s, on what was then a quiet, dusty road almost entirely devoid of traffic, peopled with white-robed gents in horsehair hats – images of a Korea long gone.

Incheon airport sleeping options

Travellers with untimely arrivals or departures often find themselves sleeping at or near Incheon International Airport, which is almost an hour from Seoul at the best of times. The good news is there’s a range of accommodation options around the airport, with many bookable on the usual search engines – those which are a little more distant usually throw in free transfers. There’s also a 24hr capsule hotel within the airport itself (![]() 032 743 5000), which is great if you just need a few hours’ rest; rates start at W7700 per hour. Alternatively, there’s a spa facility with a basic common sleeping area (W20,000), and there are free shower facilities if you just want a wash.

032 743 5000), which is great if you just need a few hours’ rest; rates start at W7700 per hour. Alternatively, there’s a spa facility with a basic common sleeping area (W20,000), and there are free shower facilities if you just want a wash.

ARRIVAL AND INFORMATION INCHEON

By plane Incheon international airport is on an island west of the city and connected to the mainland by bridge: there are dedicated airport bus connections to Seoul and all over the country. Several limousine bus routes connect the airport with central Incheon, or take city bus #306 (W1300) to Incheon subway station.

By ferry Incheon has three ferry terminals, served by ferries from China and some Korean islands in the West Sea. From all three terminals, it’s an easy taxi-ride to Jung-gu.

By subway Despite the city’s size, there’s no train station: Incheon is served by subway line 1 from Seoul (1hr), though check that your train is bound for Incheon, as the line splits when leaving the capital.

Atti 아띠 호텔 88 Sinpo-ro 35-gil ![]() 032 772 5233; map. This little gem is tucked away in a quiet area behind the Jung-gu district office, near Damjaengi restaurant. Recent renovations have seen it become a little too trendy – the big bugbears here are the glass partitions that make the bathrooms a little too visible. However, the surrounding area is highly pleasant, making it easy to put big-city bustle out of mind. W65,000

032 772 5233; map. This little gem is tucked away in a quiet area behind the Jung-gu district office, near Damjaengi restaurant. Recent renovations have seen it become a little too trendy – the big bugbears here are the glass partitions that make the bathrooms a little too visible. However, the surrounding area is highly pleasant, making it easy to put big-city bustle out of mind. W65,000

Pink Motel 핑크 모텔 4F 49 Sinpo-ro 23-gil ![]() 032 773 9984; map. If you can find it (it’s tucked away on the fourth floor of a large building), this is the cheapest motel in the area – rooms have carpets, which is a real rarity at this price level, and they’re clean enough. W25,000

032 773 9984; map. If you can find it (it’s tucked away on the fourth floor of a large building), this is the cheapest motel in the area – rooms have carpets, which is a real rarity at this price level, and they’re clean enough. W25,000

Olympos 올림포스 호텔 257 Jemullyangno ![]() 032 762 5181,

032 762 5181, ![]() olymposhotel.co.kr; map. Formerly the Paradise, this is the best hotel in Jung-gu, though the crane-filled views may not appeal to everyone. Despite being just a stone’s throw from Incheon subway station, the hotel entrance is uphill and hard to reach, so you may prefer to take a taxi. Rates can drop to as little as W65,000 midweek. W250,000

olymposhotel.co.kr; map. Formerly the Paradise, this is the best hotel in Jung-gu, though the crane-filled views may not appeal to everyone. Despite being just a stone’s throw from Incheon subway station, the hotel entrance is uphill and hard to reach, so you may prefer to take a taxi. Rates can drop to as little as W65,000 midweek. W250,000

Rarely for a Korean city, and perhaps uniquely for a Korean port, Incheon isn’t renowned for its food, though the presence of a large and thriving Chinatown is a boon to visitors. Don’t expect the food to be terribly authentic, since Koreans have their own take on Chinese cuisine. Top choices here, and available at every single restaurant, are sweet-and-sour pork (탕수육; tangsuyuk), fried rice topped with a fried egg and black-bean paste (볶음밥; beokkeumbap), spicy seafood broth (짬뽕; jjambbong), and the undisputed number one, jjajangmyeon (자장면), noodles topped with black-bean paste.

Damjaengi 담쟁이 12 Jayugongwonnam-ro

Damjaengi 담쟁이 12 Jayugongwonnam-ro ![]() 032 772 0153; map. Pleasantly old-fashioned venue under Jayu Park, selling various forms of bibimbap (most W11,000), plus Korean bar-food meant for sharing (most plates W10,000–30,000). There’s a garden out back, also featuring a tiny museum of sorts. Daily 11.30am–9pm.

032 772 0153; map. Pleasantly old-fashioned venue under Jayu Park, selling various forms of bibimbap (most W11,000), plus Korean bar-food meant for sharing (most plates W10,000–30,000). There’s a garden out back, also featuring a tiny museum of sorts. Daily 11.30am–9pm.

Gonghwachun 공화춘 43 Chinatown-ro ![]() 032 765 0571; map. This is where Korea’s jjajangmyeon fad started – it has been served here since the 1890s. W5000 will buy you a bowl, or you could try the spicy tofu on rice (W8000) or something more exotic, like the sautéed shredded beef with green pepper (W20,000), and finish off your meal with fried, honey-dipped rice balls. Not the most attractive venue, but the views from the top level are lovely. Daily 11am–11pm.

032 765 0571; map. This is where Korea’s jjajangmyeon fad started – it has been served here since the 1890s. W5000 will buy you a bowl, or you could try the spicy tofu on rice (W8000) or something more exotic, like the sautéed shredded beef with green pepper (W20,000), and finish off your meal with fried, honey-dipped rice balls. Not the most attractive venue, but the views from the top level are lovely. Daily 11am–11pm.

Origin 오리진 96 Sinpo-ro 27-gil ![]() 032 777 5527; map. Many cafés on Culture Street have gone for “old school” decor, but this one has been most faithful to the area’s Japanese past – their single tatami-based table is the obvious target, plus there’s a sculpted garden area out back. Mon & Wed–Sun 11am–10pm.

032 777 5527; map. Many cafés on Culture Street have gone for “old school” decor, but this one has been most faithful to the area’s Japanese past – their single tatami-based table is the obvious target, plus there’s a sculpted garden area out back. Mon & Wed–Sun 11am–10pm.

Incheon’s perforated western coast topples into a body of water known as the West Sea to Koreans, and the Yellow Sea to the rest of the world. Land rises again across the waves in the form of dozens of islands, almost all of which have remained pleasantly green and unspoilt; some also have excellent beaches. Life here is predominantly fishing-based and dawdles by at a snail’s pace – a world away from Seoul and its environs, despite a few being close enough to be visited on a day-trip. The easiest to reach are Ganghwado, a slightly over-busy dot of land studded with ancient dolmens, and its far quieter neighbour Gyodongdo. You’ll have to head to Incheon for ferries to the beautiful island of Deokjeokdo, which is sufficiently far away from the capital to provide a perfect escape.

강화도 • Bus #3000 (every 15–20min; 1hr 40min) from Sinchon subway in Seoul (line 2); walk directly up from exit 1

Unlike most West Sea islands, Ganghwado is close enough to the mainland to be connected by road – buses run regularly from Seoul to Ganghwa-eup (강화읍), the island’s ugly main settlement; from here local buses head to destinations across the island, though the place is so small that journeys rarely take more than thirty minutes. While this accessibility means that Ganghwado lacks the beauty of some of its more distant cousins, there’s plenty to see. One look at a map should make clear the strategic importance of the island, which not only sits at the mouth of Seoul’s main river, the Han, but whose northern flank is within a frisbee throw of the North Korean border.

Before the latest conflict, this unfortunate isle also saw battles with Mongol, Manchu, French, American and Japanese forces, among others. However, Ganghwado’s foremost sights date from even further back – a clutch of dolmens scattered around the northern part of the island dates from the first century BC and is now on UNESCO’s World Heritage list.

강화 고인돌 • Daily 24hr • Free • From Ganghwa-eup, take one of the buses bound for Changhu-ri or Gyodongdo (every hour or so), and make sure that the driver knows where you want to go

Misty remnants from bygone millennia, Ganghwa’s dolmens are overground burial chambers consisting of flat capstones supported by three or more vertical megaliths. The Korean peninsula contains more than 30,000 of these ancient tombs – almost half of the world’s total – and Ganghwado has one of the highest concentrations in the country. Most can only be reached by car or bike, though one, Ganghwa Goindol, is situated near a main road and accessible by bus. The granite tomb sits unobtrusively in a field, as it has for centuries: a stone skeleton long divested of its original earth covering, with a large 5m-by-7m capstone.

교동도 • Buses from Ganghwa-eup (11 daily; 1hr; W1300); those driving may have to register with local military; bicycles available for hire from visitor centre, by main road in Gyodong-myeon

West of Ganghwado, and newly tethered to the island by bridge, lies the bucolic island of Gyodongdo – most of the place is pancake flat, and perfect for touring by bicycle, with views across to North Korea (just 5km away) under normal weather conditions. In fact, before crossing the bridge to the island, soldiers may board the bus and ask for your reason to visit – just say “tourist” instead of “spy”, and you’re almost certain to be waved across.

Unlike Seongmodo, there’s next to no accommodation on Gyodongdo, though locals are extra friendly to the few international visitors who make it this far. The main “town”, Gyodong-myeon (교동면), is nothing more than a country village, boasting a bizarre number of dabang (다방), Korea’s original take on the café experience, and some quirky wall art. Abutting a small mountain south of Gyodong-myeon are the island’s two main sights – Gyodong Hyanggo (교동향교), a simple Confucian academy which is one of the oldest in Korea, and Hwagaesa (화개사), a charming temple just to the west.

Mr Toilet

Bar its fortress, central Suwon carries precious little sightseeing potential, though one interesting facet is what may be the world’s greatest concentration of public toilets – they all have names, and some are even marked on tourist maps. This concept was the brainchild of Sim Jae-deok, a man referred to, especially by himself, as “Mr Toilet”. Apparently afflicted by something of a cloacal obsession, Sim claimed to have been born in a public restroom, but transcended these humble beginnings to become mayor of Suwon and a member of the national assembly. He then went on to create, and declare himself head of, the other WTO – the World Toilet Organization. Undoubtedly spurred on by his team’s debatable findings that the average human being spends three years of their life on the toilet (they may need more fibre in their diet), Sim desired to improve his home city’s facilities for the World Cup in 2002, commissioning dozens of individually designed public toilets. Features may include skylights, mountain views or piped classical music, though such refinement is sadly sullied, as it is all over Korea, by the baskets of used toilet paper discarded throne-side. Sim himself died in 2009, and his old home – custom-built to resemble a giant loo – was subsequently opened to the public as the Haewoojae Museum (해우재); if you fancy tracking it down, it’s about 7km northwest of central Suwon.

덕적도 • Ferries from Incheon’s Yeonan pier (1–3 daily; 1hr 30min; W21,900 one way)

Possibly the prettiest and most tranquil of the West Sea isles, Deokjeokdo feels a world away from Seoul, though it’s quite possible to visit from the capital on a day-trip. There’s little in the way of sightseeing, save an easy climb up to the island’s main peak, and not much to do, but that’s just the point – the island has a couple of stunning beaches and some gorgeous mountain trails, and makes a refreshing break from the hustle and bustle of the mainland. Around the ferry berth are a few shops, restaurants and guesthouses, while a bus meets the ferries and makes its way round to Seopori Beach (서포리 해수욕장) on the other, quieter, side of the island – also home to a few guesthouses.

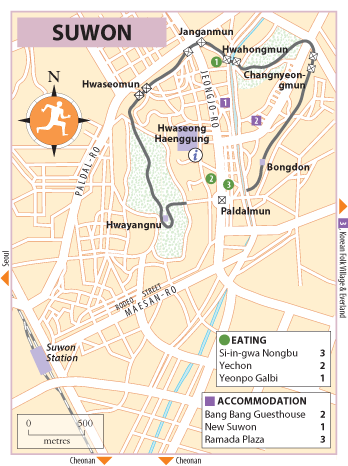

수원

Heading south from Seoul by train, the capital’s dense urban sprawl barely thins before you arrive in SUWON, a million-strong city with an impressive history of its own, best embodied by the gigantic fortress at its centre. Suwon, in fact, came close to usurping Seoul as Korea’s seat of power following the murder of prince Sado, but though it failed to overtake the capital, the city grew in importance in a way that remains visible to this day. Its fortress walls, built in the late eighteenth century, once enclosed the whole of Suwon, but from the structure’s upper reaches you’ll see just how far the city has spread, the never-ending hotchpotch of buildings now forming one of Korea’s largest urban centres. Making up for the dearth of sights in Suwon itself is an interesting and varied range of possibilities in a corridor stretching east of the city. Twenty kilometres away, the Korean Folk Village is a vaguely authentic portrayal of traditional Korean life; though too sugary for some, it redeems itself with some high-quality dance, music and gymnastic performances. Twenty-five kilometres further east is Everland, a huge amusement park.

화성 • Daily 9am–6pm • W1000 • ![]() english.swcf.or.kr • Buses #2-2, #11 and any beginning with #13, #16 or #50 from train station; #36 from bus terminal

english.swcf.or.kr • Buses #2-2, #11 and any beginning with #13, #16 or #50 from train station; #36 from bus terminal

Central Suwon has just one notable sight – Hwaseong fortress, whose gigantic walls wend their way around the city centre. Completed in 1796, the complex was built on the orders of King Jeongjo, one of the Joseon dynasty’s most famous rulers, in order to house the remains of his father, Prince Sado. Sado never became king, and met an early end in Seoul’s Changgyeong-gung Palace at the hands of his own father, King Yeongjo; it may have been the gravity of the situation that spurred Jeongjo’s attempts to move the capital away from Seoul.

Shutterstock

Ganghwado

Towering almost 10m high for the bulk of its course, the fortress wall rises and falls in a 5.7km-long stretch, most of which is walkable, the various peaks and troughs marked by sentry posts and ornate entrance gates. From the higher vantage points you’ll be able to soak up superb views of the city, though you’ll often have your reverie disturbed by screaming aircraft from the nearby military base. Most visitors start their wall walk at Paldalmun (팔달문), a gate at the lower end of the fortress, exuding a well-preserved magnificence now diluted by its position in the middle of a traffic-filled roundabout. From here there’s a short but steep uphill path to Seonammun, the western gate.

화성행궁 • March–Oct daily 9am–6pm, Nov–Feb 9am–5pm; martial arts displays Tues–Sun 11am; traditional dance and music performances April–Nov Sat & Sun 2pm • W1500

In the centre of the area bounded by the fortress walls is Hwaseong Haenggung, once a government office, then a palace, and now a fine place to amble around; its pink walls are punctuated by the green lattice frames of windows and doors, which overlook dirt courtyards from where you can admire the fortress wall that looms above. The building hosts a daily martial arts display and occasional performances of traditional dance and music.

한국 민속촌 • Generally daily 9.30am–6pm; farmers’ dance 11am & 2pm; tightrope walk 11.30am & 2.30pm; wedding ceremony 12pm & 4pm • W18,000 • ![]() koreanfolk.co.kr • Shuttle buses (30min; free) from Suwon station at 10.30am, 12.30pm & 2.30pm (returning at 1.50pm & 4pm), or take regular city bus #10-5 or #37 (50min; W1300); from Seoul take bus #5001-1 or #1560 from Gangnam station (1hr; W2500), or #5500 from Jonggak station (1hr 20min; W2500)

koreanfolk.co.kr • Shuttle buses (30min; free) from Suwon station at 10.30am, 12.30pm & 2.30pm (returning at 1.50pm & 4pm), or take regular city bus #10-5 or #37 (50min; W1300); from Seoul take bus #5001-1 or #1560 from Gangnam station (1hr; W2500), or #5500 from Jonggak station (1hr 20min; W2500)

This re-creation of a traditional Korean Folk Village has become one of the most popular day-trips for foreign visitors to Seoul, its thatch-roofed houses and dirt paths evoking the sights, sounds and some of the more pleasant smells of a bygone time, when farming was the mainstay of the country. Its proximity to the capital makes this village by far the most-visited of the many such facilities dotted around the country, which tends to diminish the authenticity of the experience. Nevertheless, the riverbank setting and its old-fashioned buildings are impressive, though the emphasis is squarely on performance, with tightrope-walking and horseriding shows taking place regularly throughout the day. Traditional wedding ceremonies provide a glimpse into Confucian society, with painstaking attention to detail including gifts of live chickens wrapped up in cloth like Egyptian mummies. Don’t miss the farmers’ dance, in which costumed performers prance around in highly distinctive ribbon-topped hats amid a cacophony of drums and crashes – quintessential Korea.

에버렌드 • Generally daily 10am–9pm • W54,000, W45,000 after 5pm • ![]() everland.com • Buses from Suwon train station (depart on the half-hour; around 1hr); from Seoul, bus #5700 from the Dong-Seoul bus terminal via Jamsil subway station (1hr 10min; W2500), or #5002 from Gangnam subway station, via Yangjae (45min; W2500); more expensive daily shuttles (50min; W12,000 return) run at 9am from Hongdae and Yongsan via City Hall, Jongno 3-ga, Gangnam and more (see website for details); or take the Everline, a spur running from the Bundang line (around 2hr in total)

everland.com • Buses from Suwon train station (depart on the half-hour; around 1hr); from Seoul, bus #5700 from the Dong-Seoul bus terminal via Jamsil subway station (1hr 10min; W2500), or #5002 from Gangnam subway station, via Yangjae (45min; W2500); more expensive daily shuttles (50min; W12,000 return) run at 9am from Hongdae and Yongsan via City Hall, Jongno 3-ga, Gangnam and more (see website for details); or take the Everline, a spur running from the Bundang line (around 2hr in total)

Everland is a colossal theme park that ranks as one of the most popular domestic tourist attractions in the country – male or female, young or old, it’s hard to find a hangukin (Korean person) who hasn’t taken this modern-day rite of passage, and more than seven million visitors pass through the turnstiles each year. Most are here for the fairground rides, and the park has all that a roller-coaster connoisseur could possibly wish for. Other attractions include a zoo (which features a safari zone that can be toured by bus, jeep or even at night), a speedway track and a golf course.

케리비언 베이 • Generally daily 9.30am–6pm; outdoor section June–Aug only • W42,000, W36,000 after 2.30pm; discount and combination tickets often available on website • ![]() everland.com

everland.com

The most popular part of the theme park is Caribbean Bay, with a year-round indoor zone containing several pools, a sauna and a short river that you can float down on a tube, as well as massage machines and relaxation capsules. The outdoor section with its man-made beach is what really draws the summer crowds. Other facilities include an artificial surfing facility, and a water bobsleigh, which drops you the height of a ten-floor building in just ten seconds.

ARRIVAL AND INFORMATION SUWON AND AROUND

By train and subway Within walking distance of the fortress, Suwon’s main train station handles both national rail and Seoul subway trains (line 1), though this splits south of Seoul. The train from Seoul is quicker (30min) and far more comfortable than the subway (1hr), though it’s more expensive.

Transport cards Seoul transport cards can be used for buses or subway trains in Suwon.

Tourist information The main information office is just to the left of the main station exit (daily 9am–8pm; ![]() 031 228 4672), and there’s a small office visible from Hwaseong Haenggung.

031 228 4672), and there’s a small office visible from Hwaseong Haenggung.

Most travellers visit on day-trips from the capital; there are groups of motels in the area bounded by the fortress wall, but you’d do well to disregard all images that staying inside a UNESCO-listed sight may bring to mind, as it’s one of the seedier parts of the city. True budget-seekers can make use of an excellent jjimjilbang just off Rodeo Street (W7000).

Bang Bang Guesthouse 방방 게스트하우스 16 Changnyong-daero 41-gil

Bang Bang Guesthouse 방방 게스트하우스 16 Changnyong-daero 41-gil ![]() 010 3792 3525; map. The best of Suwon’s several hostel-like affairs, and just a short walk from the fortress walls (if a little distant from the train station). Beds are surprisingly large for a hostel, the common areas encourage mingling, and the owners are friendly English-speakers. Breakfast included. Dorms W25,000, doubles W60,000

010 3792 3525; map. The best of Suwon’s several hostel-like affairs, and just a short walk from the fortress walls (if a little distant from the train station). Beds are surprisingly large for a hostel, the common areas encourage mingling, and the owners are friendly English-speakers. Breakfast included. Dorms W25,000, doubles W60,000

New Suwon 뉴 수원 호텔 33 Hwaseomun-ro 72-gil ![]() 031 245 2405; map. A good mid-budget option, close to the fortress. Rooms feature all mod cons from slippers to hairdryers, but since some are a little on the small side, ask to see before checking in; it’s often worth shelling out the extra W10,000 or so for a deluxe berth. W55,000

031 245 2405; map. A good mid-budget option, close to the fortress. Rooms feature all mod cons from slippers to hairdryers, but since some are a little on the small side, ask to see before checking in; it’s often worth shelling out the extra W10,000 or so for a deluxe berth. W55,000

Ramada Plaza 라마다프라자 150 Jungbu-daero ![]() 031 230 0001,

031 230 0001, ![]() ramadaplazasuwon.com; map. Suwon’s best hotel, though in an uninteresting corner of the city, attracts well-heeled visitors – primarily Europeans on business – and offers all the comfort you’d expect of the chain. Some of the suites are truly stunning, and even standard rooms have been designed with care; oddly, rates often drop on weekends. W220,000

ramadaplazasuwon.com; map. Suwon’s best hotel, though in an uninteresting corner of the city, attracts well-heeled visitors – primarily Europeans on business – and offers all the comfort you’d expect of the chain. Some of the suites are truly stunning, and even standard rooms have been designed with care; oddly, rates often drop on weekends. W220,000

Suwon is famous for a local variety of galbi, whereby the regular meat dish is given a salty seasoning. You will more than likely find something appealing on Rodeo Street, where the city’s youth flocks to in the evening to take advantage of the copious cheap restaurants.

Si-in-gwa Nongbu 시인과 농부 8 Jeongjo-ro 796-gil ![]() 031 245 0049; map. Great little tearoom just north of Paldalmun, “The Poet and the Farmer” has charming decor and the usual range of Korean teas (most around W5500); alternatively, think about trying something more left-field, such as the sujeonggwa (cinnamon punch; W4500). Mon & Wed–Sun 10am–10pm.

031 245 0049; map. Great little tearoom just north of Paldalmun, “The Poet and the Farmer” has charming decor and the usual range of Korean teas (most around W5500); alternatively, think about trying something more left-field, such as the sujeonggwa (cinnamon punch; W4500). Mon & Wed–Sun 10am–10pm.

Yechon 예촌 49-4 Haenggung-ro ![]() 031 254 9190; map. It’s retro to the max at this little hidey-hole near Paldalmun, a folk-styled establishment serving savoury pancakes known as jeon (전) in many different styles (from W10,000), as well as superb makgeolli from Jeonju, a city in the southwest of the country. Tues–Sun 3.30pm–midnight.

031 254 9190; map. It’s retro to the max at this little hidey-hole near Paldalmun, a folk-styled establishment serving savoury pancakes known as jeon (전) in many different styles (from W10,000), as well as superb makgeolli from Jeonju, a city in the southwest of the country. Tues–Sun 3.30pm–midnight.

Yeonpo Galbi 연포 갈비 56-1 Jeongjo-ro 906-gil

Yeonpo Galbi 연포 갈비 56-1 Jeongjo-ro 906-gil ![]() 031 255 1337; map. In a quiet area just inside the fortress wall lies the best restaurant in the area. The meat is fair value (W14,000 a portion, minimum two), but cheaper noodle dishes are available, and those who arrive before 3pm can get a huge jeongsik (set meal) for W20,000, which includes several small fish and vegetable dishes. Daily 9am–9pm.

031 255 1337; map. In a quiet area just inside the fortress wall lies the best restaurant in the area. The meat is fair value (W14,000 a portion, minimum two), but cheaper noodle dishes are available, and those who arrive before 3pm can get a huge jeongsik (set meal) for W20,000, which includes several small fish and vegetable dishes. Daily 9am–9pm.

양수리

A tranquil village surrounded by mountains and water, YANGSU-RI sits at the confluence of the Namhangang and Bukhangang, two rivers that merge to create the Hangang, which pours through Seoul. The village has long had a reputation as a popular spot for extra-marital affairs, though in recent years its natural charm has also started to draw in an ever-increasing number of families, students and curious foreign visitors.

The focus of the village is a small island, with farmland taking up much of its interior. A pleasant walking track skirts the perimeter – the stretch to the south is particularly enjoyable, with the very southern tip being a spectacular spot to watch the sunset.

By subway Yangsu is a stop on the Gyeongui-Jungang line – the journey takes around an hour from Yongsan. It’s a 15min walk to the island from Yangsu station, though it’s also possible to take a bus. It’s also possible (and more pleasurable) to access the island from Ungilsan, the station immediately west of Yangsu – from here, simply find the bridge, and walk across.

By bike Though it may be more than 35km from central Seoul, Yangsu-ri is becoming more and more popular as a bike trip from the capital: it’s certainly within day-trip distance for regular riders. You can also rent bikes at Yangsu-ri itself: there’s a booth immediately outside Yangsu station, and another within visible distance of Ungilsan station. Cycling the island’s perimeter is very pleasant, and the track even continues all the way down to Busan.

Gelateria Panna 빤나 4 Yangsu-ro 155-gil

Gelateria Panna 빤나 4 Yangsu-ro 155-gil ![]() 031 775 4904. It’s quite odd to think that wider Seoul’s best ice cream should be found way out in Yangsu-ri, but it’s true – the couple that run this tiny place lived in Milan for a decade, and during that time learned how to make some kick-ass gelato (from W3500 for a scoop). Their ice-cream roster changes daily (the ginger and vanilla are particularly tasty), and they also make a mean espresso (W2500). It’s in the village, just south of the main road. Wed–Sun 11am–8pm.

031 775 4904. It’s quite odd to think that wider Seoul’s best ice cream should be found way out in Yangsu-ri, but it’s true – the couple that run this tiny place lived in Milan for a decade, and during that time learned how to make some kick-ass gelato (from W3500 for a scoop). Their ice-cream roster changes daily (the ginger and vanilla are particularly tasty), and they also make a mean espresso (W2500). It’s in the village, just south of the main road. Wed–Sun 11am–8pm.

Jeongmune Jangeojip 정무네 장어집 27-1 Yangsu-ro 152-gil ![]() 031 577 8697. Yangsu-ri has found fame as a place for grilled river eel, and this pleasing clutch of wooden buildings – set near the river on the western side of the village, just north of the bridge – is as good a place as any to wolf some down (W24,000 per portion, min two). They also have cheap jeon pancakes, including a kimchi varietal (W7000), and super-cheap janchi-guksu (noodles in an anchovy broth; W4000). Mon, Tues & Wed–Sun 11am–8pm.

031 577 8697. Yangsu-ri has found fame as a place for grilled river eel, and this pleasing clutch of wooden buildings – set near the river on the western side of the village, just north of the bridge – is as good a place as any to wolf some down (W24,000 per portion, min two). They also have cheap jeon pancakes, including a kimchi varietal (W7000), and super-cheap janchi-guksu (noodles in an anchovy broth; W4000). Mon, Tues & Wed–Sun 11am–8pm.

iStock

Hwaseong fortress

공주

Presided over by the large fortress of Gongsanseong, small, sleepy GONGJU is one of Korea’s most charming cities, and the best place to see relics from the Baekje dynasty that it ruled as capital in the fifth and sixth centuries. Once known as Ungjin, Gongju became the second capital of the realm in 475, but only held the seat of power for 63 years before it was passed to Buyeo, a day’s march to the southwest. Today, the city is largely devoid of bustle, clutter and chain stores, and boasts a number of wonderful sights, including a hilltop fortress and a museum containing a fine collection of Baekje jewellery. It is also home to some excellent restaurants, and hosts the Baekje Cultural Festival (![]() baekje.org) each September/early October, with colourful parades and traditional performances in and around the city.

baekje.org) each September/early October, with colourful parades and traditional performances in and around the city.

공산성 • Daily 9am–6pm • Changing of the guard April–June, Sept & Oct daily 2pm • W1200

For centuries, Gongju’s focal point has been the hilltop fortress of Gongsanseong, whose 2.6km-long perimeter wall was built from local mud in Baekje times, before receiving a stone upgrade in the seventeenth century. It’s possible to walk the entire circumference of the wall, a flag-pocked, up-and-down course that occasionally affords splendid views of Gongju and its surrounding area. The grounds inside are worth a look too, inhabited by striped squirrels and riddled with paths leading to a number of carefully painted pavilions. Of these, Ssangsujeong has the most interesting history – where this now stands, a Joseon-dynasty king named Injo (r.1623–49) once hid under a couple of trees during a peasant-led rebellion against his rule; when this was quashed, the trees were made government officials, though sadly they’re no longer around to lend their leafy views to civil proceedings. Airy, green Imnyugak, painted with meticulous care, is the most beautiful pavilion; press on further west down a small path for great views of eastern Gongju. Down by the river there’s a small temple, a refuge to monks who fought the Japanese in 1592, and on summer weekends visitors can dress up as a Baekje warrior and shoot off a few arrows.

무령왕릉 • Daily 9am–6pm • W1500

West over the creek from Gongsanseong, the Tomb of King Muryeong is one of many burial groups dotted around the country from the Three Kingdoms period, but the only Baekje mound whose occupant is known for sure. Muryeong, who ruled for the first quarter of the sixth century, was credited with strengthening his kingdom by improving relations with China and Japan; some accounts suggest that the design of Japanese jewellery was influenced by gifts that he sent. His gentle green burial mound was discovered by accident in 1971 during a construction project – after fifteen centuries, Muryeong’s tomb was the only one that hadn’t been looted, and it yielded thousands of pieces of jewellery that provided a fascinating insight into the craft of the Baekje people. All the tombs have now been sealed off for preservation, but a small exhibition hall contains replicas of Muryeong’s tomb and the artefacts found within.

공주 한옥 마을 • Daily 24hr • Free

A short walk from the regal tombs is Gongju Hanok Village, a decent recreation of a Baekje-era village – though one complete with café, restaurants and a convenience store. Unlike its counterparts in Seoul and Jeonju, this is a tourist construct rather than a functional part of the city; nevertheless, it makes good camera fodder, and you may find yourself tempted to sleep (see below) in these unusual environs.

공주 국립 박물관 • Tues–Sun 9am–6pm • Free • ![]() gongju.museum.go.kr • Get bus #108 from the bus terminal (W1400), or take a taxi (around W4000)

gongju.museum.go.kr • Get bus #108 from the bus terminal (W1400), or take a taxi (around W4000)

In a quiet wooded area by the turn of the river, Gongju National Museum is home to many of the treasures retrieved from Muryeong’s tomb. Much of the museum is devoted to jewellery, and an impressive collection of Baekje bling reveals the dynasty’s penchant for gold, silver and bronze. Artefacts such as elaborate golden earrings show an impressive attention to detail, but manage to be dignified and restrained in their use of shape and texture. The highlight is the king’s flame-like golden headwear, once worn like rabbit ears on the royal scalp, and now one of the most important symbols not just of Gongju, but of the Baekje dynasty itself. Elsewhere in the museum exhibits of wood and clay show the dynasty’s history of trade with Japan and China.

By bus Direct buses from the express bus terminal in Seoul (1–2 hourly; 1hr 20min) arrive at Gongju’s bus terminal, just north of the Geumgang River; you can walk from here to all the main sights, though taxi rides are cheap.

Information The main tourist information centre (daily: summer 9am–6pm; winter 9am–5pm; ![]() 041 856 7700) is beneath Gongsanseong, and usually has helpful, English-speaking staff.

041 856 7700) is beneath Gongsanseong, and usually has helpful, English-speaking staff.

Gongju has a poor selection of accommodation, with motels centred in two areas: north of the river, to the west of the bus terminal, is a bunch of newer establishments (including a couple of cheesy replica “castles”), while a group of older cheapies lies south of the river across the road from Gongsanseong. The latter is a quainter and more atmospheric area, and slightly closer to the sights, but the newer rooms are far more comfortable.

Hanok Gongju 한옥 공주 12 Gwangwangdanji-gil

Hanok Gongju 한옥 공주 12 Gwangwangdanji-gil ![]() 041 840 8900. A splendidly pretty little faux hamlet of traditional wooden hanok housing, sitting in calm isolation between the tombs and museum. Though recently constructed, the buildings certainly feel real enough, and are heated from beneath by burning wood; they’re spartan, for sure, but the location is relaxing, and the experience somewhat unique. Prices come down to W50,000 on weekdays. W70,000

041 840 8900. A splendidly pretty little faux hamlet of traditional wooden hanok housing, sitting in calm isolation between the tombs and museum. Though recently constructed, the buildings certainly feel real enough, and are heated from beneath by burning wood; they’re spartan, for sure, but the location is relaxing, and the experience somewhat unique. Prices come down to W50,000 on weekdays. W70,000

Kumgang 호텔 금강 Singwandong 595-8 ![]() 041 852 1071. The only official “hotel” in town, though in reality it’s basically a smarter-than-average motel with a few twins and triples. However, it has friendly staff, spacious bathrooms and on-demand TV in all rooms, and should suffice for all but the fussiest travellers. Prices come down a little on weekdays. W60,000

041 852 1071. The only official “hotel” in town, though in reality it’s basically a smarter-than-average motel with a few twins and triples. However, it has friendly staff, spacious bathrooms and on-demand TV in all rooms, and should suffice for all but the fussiest travellers. Prices come down a little on weekdays. W60,000

Gomanaru 고마나루 5-9 Bengmigoeul-gil

Gomanaru 고마나루 5-9 Bengmigoeul-gil ![]() 041 857 9999. This restaurant is, quite simply, one of Korea’s most enjoyable places to eat. Their huge ssam-bap (쌈밤) sets feature a – quite literal – tableful of largely veggie side dishes, and over a dozen kinds of leaves to eat them with. There are a few choices for the centrepiece of the meal, though the barbecued duck is highly recommended (W13,000, minimum two people); an extra W7000 will see the whole shebang covered with edible flowers, which is absolute heaven. Solo diners will have to content themselves with a flower bibimbap (W12,000) – this comes with a mere dozen side-dishes. Daily 11am–9pm.

041 857 9999. This restaurant is, quite simply, one of Korea’s most enjoyable places to eat. Their huge ssam-bap (쌈밤) sets feature a – quite literal – tableful of largely veggie side dishes, and over a dozen kinds of leaves to eat them with. There are a few choices for the centrepiece of the meal, though the barbecued duck is highly recommended (W13,000, minimum two people); an extra W7000 will see the whole shebang covered with edible flowers, which is absolute heaven. Solo diners will have to content themselves with a flower bibimbap (W12,000) – this comes with a mere dozen side-dishes. Daily 11am–9pm.

Marron Village 밤마을 5-9 Bengmigoeul-gil ![]() 041 853 3489. One of a pair of pine buildings opposite the fortress, this bakery sells buns made with local chestnuts. However, you may find it more useful for incredibly cheap coffee – W2000 will get you a decent Americano, which you can have on the upper level with a view of the fortress walls. Daily 9am–10pm.

041 853 3489. One of a pair of pine buildings opposite the fortress, this bakery sells buns made with local chestnuts. However, you may find it more useful for incredibly cheap coffee – W2000 will get you a decent Americano, which you can have on the upper level with a view of the fortress walls. Daily 9am–10pm.