Shutterstock

Bukchon Hanok Village

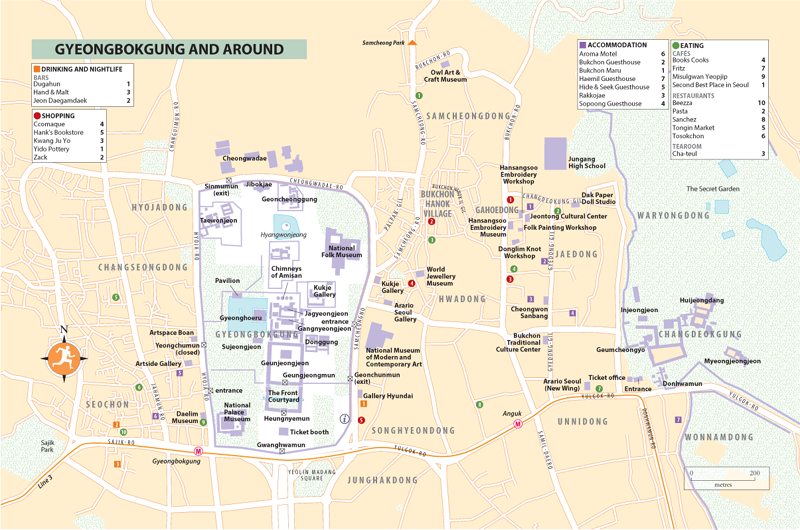

Seoul is one of the world’s largest urban agglomerations, racing out for kilometre after kilometre in every direction, and swallowing up whole cities well beyond its own official limits. As such, it’s hard to imagine that the Korean capital was once a much smaller place, bounded by fortress walls erected shortly after the nascent Joseon dynasty chose it as their seat of power in 1392. The palace of Gyeongbokgung was built during these fledgling years, and centuries down the line its environs are still the seat of national power. The oldest and most historically important of Seoul’s five palaces, Gyeongbokgung attracts the greatest number of visitors and boasts a splendid mountain backdrop, as well as two great museums.

Abutting Gyeongbokgung to the northeast is the neighbourhood of Samcheongdong, a trendy, laidback area filled with cafés, galleries, wine bars and clothing boutiques. Across a small ridge, hilly Bukchon Hanok Village is one of the few pockets of traditional architecture remaining in the city – its wooden, tile-roofed buildings shelter plenty of tearooms and traditional culture. Beyond Bukchon Hanok Village, the palace of Changdeokgung is the only one of Seoul’s palaces to have been awarded UNESCO World Heritage status: a little more refined than Gyeongbokgung, it has superb architecture and a charming garden. Heading west from Gyeongbokgung will bring you to Seochon, a trendy area popular with discerning expats and locals.

경복궁 • 161 Sajik-ro • Mon & Wed–Sun: March–Oct 9am–6pm; Nov–Feb 9am–5pm; English-language tours Mon & Wed–Sun 11am, 1.30pm & 3.30pm (free); changing of the guard Mon & Wed–Sun 10am, 1pm & 3pm • W3000; also on combination ticket (see above) • ![]() royalpalace.go.kr • Gyeongbokgung subway (line 3)

royalpalace.go.kr • Gyeongbokgung subway (line 3)

The glorious palace of Gyeongbokgung is, with good reason, the most popular tourist sight in the city, and a focal point of the country as a whole. The place is quite absorbing, and the stroll along the dusty paths between its delicate tile-roofed buildings is one of the most enjoyable experiences Seoul has to offer. Gyeongbokgung was ground zero for Seoul’s emergence as a place of power, having been built to house the royal family of the embryonic Joseon dynasty, shortly after they transferred their capital here in 1392. The complex has witnessed fires, repeated destruction and even a royal assassination, but careful reconstruction means that the regal atmosphere of old is still palpable, aided no end by the suitably majestic crags of Bugaksan to the north. A large historical complex with excellent on-site museums, it will easily eat up the best part of a day to see it all.

Substantial reconstruction of Gyeongbokgung began in earnest in 1989, when the city government embarked on a mammoth forty-year campaign to re-create the hundreds of buildings that once filled the palace walls. The Seoul Capitol, which was used after the war as the Korean National Assembly, then the National Museum, was finally torn down on Independence Day in 1995. More than half of Gyeongbokgung’s former buildings have now been rebuilt, and the results are extremely pleasing. Particularly noteworthy was the reopening of Gwanghwamun in 2010, since this was the first time Korea’s most famous palace gate had been present in its original position, and built with traditional materials, since the fall of Joseon.

Construction of the “Palace of Shining Happiness” was ordered by King Taejo in 1394 and completed in 1399: it then held the regal throne for over two hundred years. At the peak of its importance, the palace housed over four hundred buildings within its vaguely rectangular perimeter walls, but most were burnt down during the Japanese invasions in the 1590s. Though few Koreans will admit it, the invaders were not always to blame – the arsonists in one major fire were actually a group of local slaves, angered by their living and working conditions, and aware that their records were kept locked up in the palace. The palace was only rebuilt following the coronation of child-king Gojong in 1863, but these renovations were destined to be short-lived thanks to the expansionist ideas of contemporary Japan, who in 1895 removed one major obstacle to power by assassinating Gojong’s wife, Empress Myeongsong, in the Gyeongbokgung grounds, before making a formal annexation of the peninsula in 1910. Gyeongbokgung, beating heart of an occupied nation, was first in the line of fire and, all in all, only a dozen of the palace’s buildings survived the occupation period.

Under Japanese rule, the palace was used for police interrogation and torture, and numerous structural changes were made in an apparent effort to destroy Korean pride. The front gate, Gwanghwamun, was moved to the east of the complex, destroying the north–south geometric principles followed during the palace’s creation, while 1926 saw the construction of the Seoul Capitol, a huge Neoclassical Japanese construction that became the city’s largest building at the time, dwarfing the former royal structures around it, and making a rather obvious stamp of authority. Other insinuations were more subtle – viewed from above, the building’s shape was identical to the Japanese written character for “sun” (日). One interesting suggestion, and one certainly not beyond the scope of Japanese thinking at that time, is that Bukhansan mountain to the north resembled the character for “big” (大) and City Hall to the south – also built by the Japanese – that of “root” (本), thereby emblazoning Seoul’s most prominent points with the three characters that made up the written name of the Empire of the Rising Sun (大日本).

Gyeongbokgung remained a locus of power after the Japanese occupation ended with World War II in 1945; the American military received the official Japanese surrender at the Seoul Capitol, and in 1948 Syngman Rhee, the first president of Korea, took his oath on the building’s front steps. Then, of course, came the Korean War (1950–53), during which Seoul changed hands four times, and the palace complex suffered damage so extensive that renovations are not yet complete.

Most visitors start their tour at the palace’s southern gate, Gwanghwamun (광화문), though there’s another entrance on the eastern side of Gyeongbokgung. Entering through the first courtyard, you’ll see Geunjeongjeon (근정전), the palace’s former throne room, looming ahead. Despite being the largest wooden structure in the country, this two-level construction remains surprisingly graceful, the corners of its gently sloping roof home to lines of small guardian figurines, beneath which dangle tiny bells. The central path leading up to Geunjeongjeon was once used only by the king. However, the best views of its interior are actually from the sides – from here you’ll see the golden dragons on the hall ceiling, as well as the throne itself, backed by its traditional folding screen.

After Geunjeongjeon you can take one of a number of routes around the complex. To the east of the throne room are the buildings that once housed crown princes, deliberately placed here to give these regal pups the day’s first light, while behind is Gangnyeongjeon (강녕전), the former living quarters of the king and queen, furnished with replica furniture. Also worth seeking out is Jagyeongjeon (자경전), a building backed by pink-brick chimneys, once used to direct smoke outwards from the living quarters’ ondol (an ingenious underfloor heating system still employed in Korean apartments today).

경회루 • Tours April–Oct Mon & Wed–Fri 10am, 2pm & 6pm, Sat & Sun 10am, 11am, 2pm, 6pm • Free, but limited to 100 visitors per session (of which only 20 reservable by non-Koreans) • Book online at ![]() royalpalace.go.kr, and bring passport

royalpalace.go.kr, and bring passport

West of the throne room is Gyeonghoeru (경회루), a colossal pavilion looking out over a tranquil lotus pond that was a favourite with artists in imperial times; it remains so today, though limited tours are available, and only in season. Its surrounding pond was also used as a ready source of water for the fires that regularly broke out around the palace (an unfortunate by-product of heating buildings using burning wood or charcoal under the floor), while the pavilion itself was used for the civil service examinations that became an integral part of aristocratic life in Joseon times.

To the north again, and past another pond, is Geoncheonggung (건청궁), a freshly renovated miniature palace famed as the venue of Empress Myeongseong’s assassination. At the beginning of the twentieth century, there was actually a Western-style building on these grounds, providing evidence of how the reclusive “Hermit Kingdom” of Joseon opened up to foreign ideas in its final years. This building, now destroyed, was designed by Russian architect A.S. Seredin-Sabatin, who was visiting at the time of the assassination, and witnessed the murder himself.

Shutterstock

Gyeongbokgung

One foreign-themed building still in existence is Jibokjae (지복재), just to the west, a miniature palace constructed in 1888 during the rule of King Gojong to house books and works of art. Designed in the Chinese style that was the height of fashion at the time, this building is markedly different from any other structures around the palace, particularly the two-storey octagonal pavilion on its western end. Geoncheonggung sits right next to the palace’s northern exit, but if you still have a little energy to spare, press on further west to Taewonjeon (태원전), a relatively new clutch of buildings. Though there’s little of historical interest here, the area’s mountain views and relative dearth of visitors make it the perfect end to a tour around the palace.

국립민속박물관 • Mon & Wed–Sun: Mar–Oct 9am–6pm; Nov–Feb 9am–5pm • Entrance included in palace ticket • ![]() nfm.go.kr

nfm.go.kr

On the east of the palace complex is the diverting National Folk Museum, a traditionally styled, multi-tier structure that fits in nicely with the palatial buildings. Despite its size, there’s only one level, but this is stuffed with dioramas and explanations of Korean ways of life long since gone, from fishing and farming practices to examples of clothing worn during the Three Kingdoms era (c.57 BC – 668 AD). Children may well find the exhibits more interesting than slogging around the palace buildings, plus there’s a gift shop and small café near the entrance, which makes it an excellent pit stop for those who need to take a break.

국립고궁박물관 • Mon–Fri 9am–6pm, Sat & Sun 9am–7pm; English-language tours (free) at 11am & 2.30pm • Free • ![]() gogung.go.kr

gogung.go.kr

At the far southwest of the palace grounds is the National Palace Museum. This was the site of the National Museum until 2005, when it moved to a new location, leaving behind exhibits related to the Seoul palaces. The star of the show here is a Ilwolobongdo, a folding screen which would have once been placed behind the imperial throne, and features the sun (the il from the name), moon (that’s the wol) and five peaks (obong) painted onto a dark blue background, symbolically positioning the seated kings at the nexus of heaven and earth. It’s a glorious, significant piece of art that deserves to be better known. Other items in the fascinating display include a jade book belonging to King Taejo, some paraphernalia relating to ancestral rites, and some of the wooden dragons taken from the temple eaves, whose size and detail can be better appreciated when seen up close. Equally meticulous is a map of the heavens, engraved onto a stone slab in 1395.

서촌

Immediately to the west of Gyeongbokgung is a mix of eclectic neighbourhoods – these are often banded together under the name Seochon, which means “west village”. As recently as 2013, few non-locals ventured here, yet today it is one of Seoul’s trendiest locales. Most come to eat, drink and be merry in Sejong Maeul, a small but popular street lined with charming restaurants; it was named after King Sejong, the creator of the Korean alphabet, and you’ll see that businesses lining the main road to the east all sport signs in hangeul, rather than Roman letters. Elsewhere, Artside and the Daelim Museum are the best of the area’s many gallery spaces, while Tongin Market lures locals with its earthy vibe, and an admirably zany meal scheme.

다림미술관 • 21 Jahamun-ro 4-gil • Tues–Sun 10am–6pm • Most exhibitions W5000 • ![]() daelimmuseum.org • Gyeongbokgung subway (line 3)

daelimmuseum.org • Gyeongbokgung subway (line 3)

One of Seoul’s most highly regarded galleries, the Daelim Museum hosts a string of fascinating temporary exhibitions, with the focus on photography. Past contributors have included Karl Lagerfeld and Stella McCartney, though the curators also branch off into other fields: clothes from Paul Smith and furniture from Jean Prouvé have been on display during past exhibitions.

아트스페이스 보안 • 33 Hyoja-ro • Tues–Sun 10am–6pm • Free, though fee occasionally levied for special exhibitions • ![]() artside.org • Gyeongbokgung subway (line 3)

artside.org • Gyeongbokgung subway (line 3)

Extremely intriguing whatever the exhibition, Artspace Boan is set in a former yeogwan (inn) dating to 1942. Though it’s borderline dilapidated, much of the old structure has been left intact; given the resultant appeal, exhibitions can often feel a bit incidental, though they continue on into an adjoining modern wing.

삼청동

The youthful district of Samcheongdong is crammed with restaurants, cafés and galleries, many of which have a contemporary appearance. Though a bit on the wane after a brief period in the sun, the area’s maze of tiny streets is regularly jam-packed with camera-toting youngsters – especially on warm weekend afternoons. The area’s charming main drag, Samcheongdonggil (삼청동길), heads off from Gyeongbokgung’s northeastern corner – a mere five-minute walk from the palace’s eastern exit. The district is also home to Korea’s most important road in artistic terms, Samcheongno, which runs along the eastern flank of the palace and sports a number of excellent art galleries (see box below), as well as the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art.

국립미술관 • 30 Samcheong-ro • Tues, Thurs, Fri & Sun 10am–6pm, Wed & Sat 10am–9pm • W4000; free Wed & Sat after 6pm • ![]() mmca.go.kr • Anguk subway (line 3); four daily shuttle buses run to their other location in Gwacheon

mmca.go.kr • Anguk subway (line 3); four daily shuttle buses run to their other location in Gwacheon

Opened in late 2013, this third wing of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art boasts an interesting history – this site was, among other things, once home to the national Taoist temple, the Gyeongbokgung library, the Joseon Office of Censors and the Office of Royal Genealogy. The main building, now renovated, was erected to house the Japanese Defence Security Command during the occupation. Despite the building’s history, the art on display today is most definitely modern and contemporary. There’s no permanent display, but all the exhibitions (there’s usually a new one every two weeks) are highly creative. Start your visit in the open-air Madang Gallery, a space inspired by the Turbine Hall in London’s Tate Modern.

청와대 • 1 Sejong-ro • Guided tours Tues–Sat at 10am, 11am, 2pm & 3pm • Free, but must be booked at ![]() english.president.go.kr at least three weeks in advance; bring your passport and collect tickets at Gyeongbokgung • Gyeongbokgung or Anguk subway (both line 3)

english.president.go.kr at least three weeks in advance; bring your passport and collect tickets at Gyeongbokgung • Gyeongbokgung or Anguk subway (both line 3)

What the White House is to Washington, Cheongwadae is to Seoul. Sitting directly behind Gyeongbokgung and surrounded by mountains, this official presidential residence is sometimes nicknamed the “Blue House” on account of the colour of its roof tiles. In Joseon times, blue roofs were reserved for kings, but the office of president is the nearest modern-day equivalent. This is not without its hazards: in 1968, there was an attempt here to assassinate then-President Park Chung-hee. Security measures mean that it’s only possible to visit Cheongwadae on a guided tour. Unfortunately, tours do not include any of the main buildings, so visitors will have to be content with strolling around the luscious gardens, and popping into the occasional shrine.

Note that even if you’re not visiting Cheongwadae, the road bordering the palace is a high-security area; while you’re unlikely to be accused of wanting to assassinate the incumbent head of state, those loitering or straying too close are likely to be questioned.

부엉이 박물관 • 143-10 Bukchon-ro • Wed–Sat 10am–7pm • W5000 • Anguk subway (line 3)

The result of its founder’s quirky (and slightly scary) obsession, the tiny Owl Art & Craft Museum is stuffed to the gills with anything and everything pertaining to owls. There’s a small tearoom-cum-café in which you can purchase strigiform trinkets of your very own.

세계 장신구 박물관 • 2 Bukchon-ro 5-gil • Wed–Sun 11am–5pm • W7000 • ![]() wjmuseum.com • Anguk subway (line 3)

wjmuseum.com • Anguk subway (line 3)

With a name that’s as coldly descriptive as they come, the World Jewellery Museum is, perhaps surprisingly, the most rewarding of the many quirky museums found across the Bukchon area. As its name suggests, the pieces on display have been hauled from all across the globe, and there’s an admirable subtlety and variety to the collection.

삼청공원 • 41 Waryonggongwon-gil • Daily 24hr • Free • Anguk subway (line 3)

At the top of Samcheongdonggil, Samcheong Park is a small but delightful spot that for some reason never finds itself overrun with visitors, even on the sunniest Sunday of the year. It was Korea’s first-ever officially designated park, having been awarded said status in 1940, and its leafy, sheltered trails make for fantastic walking. The park can also be used as an entry point for the loftier trails of Bugaksan.

북촌 한옥 마을

Although it has few actual sights, Bukchon Hanok Village is one of the city’s most characterful areas and there’s some delightful walking to be done among this web of quiet, hilly lanes, checking out the odd café, picturesque view or traditional workshop (see box below) along the way. Despite being just across the road from Insadong and its teeming tourists, Bukchon feels a world apart, with its cascades of tiled rooftops, and a pleasing clutch of tearooms and traditional museums.

The area is characterized by its traditional wooden hanok buildings, which have been saved from demolition by the city authorities, partly due to their proximity to the presidential abode, and partly because of protest movements led by locals; a few of the buildings have even been converted into guesthouses. Hanok housing once covered the whole country, but most of those lucky enough to survive the Japanese occupation and civil war were torn down during the country’s economic revolution, and replaced with rows of sterile fifteen-storey blocks – it’s estimated that today more than seventy percent of the country’s population lives in high-rise apartment buildings. Even in Bukchon, many of the hanok houses are far from traditional, with basement levels, garages, Western-style beds and other modern accoutrements, but one can forgive these necessary concessions to the modern day when the end result is so charming.

북촌 한옥 1길 • Daily 24hr • Free • Anguk subway (line 3)

Many Bukchon visitors make a beeline to Bukchon Hanok Il-gil, a steep lane with a particularly good view of the hanok abodes. From the top of the lane, the high-rise architecture of the City Hall area is impossible to ignore – standing behind such wonderful original structures, this quintessential “tradition-meets-modernity” view certainly poses questions about how Korea might have looked had its progress been a little more gentle.

중앙고등학교 • 164 Changdeokgung-gil • Daily 24hr; closed during class times • Free • Anguk subway (line 3)

While on a Bukchon stroll you may come across Jungang High School, built in the 1930s along vaguely Tudor architectural lines. Backing onto Changdeokgung, the compound is well worth a stroll when open to visitors, and the quirky Pasta restaurant is just outside the front gates.

창덕궁 • 99 Yulgok-ro • Tues–Sun: Feb–Oct 9am–6pm; Nov–Jan 9am–5.30pm; Secret Garden by tour only, usually on the hour 10am–4pm; English-language palace tours at 10.30am, 11.30 & 2.30pm, plus 3.30pm Feb–Nov • Palace W3000; Secret Garden an additional W5000; both also on combination ticket • ![]() eng.cdg.go.kr • Anguk subway (line 3)

eng.cdg.go.kr • Anguk subway (line 3)

Sumptuous Changdeokgung is, for many, the pick of Seoul’s palaces, with immaculate paintwork and carpentry augmenting a palpable sense of history – home to royalty as recently as 1910, it’s the best-preserved palace in the city. Its construction was completed in 1412, under the reign of King Taejong. Like Gyeongbokgung, it suffered heavy damage during the Japanese invasions of the 1590s; Gyeongbokgung was left to fester, but Changdeokgung was rebuilt and in 1618 usurped its older brother as the seat of the royal family, an honour it held until 1872. In its later years, the palace became a symbol of Korea’s opening up to the rest of the world – King Heonjong (r.1834–49) added distinctively Chinese-style buildings to the complex, and his eventual successor King Sunjong (r.1907–10) was fond of driving Western cars around the grounds. Sunjong was, indeed, the last of Korea’s long line of kings; Japanese annexation brought an end to his short rule, but he was allowed to live in Changdeokgung until his death in 1926. This regal lineage still continues today, though claims are contested and the “royals” have no regal rights, claims or titles.

The huge gate of Donhwamun is the first structure you’ll come across – dating from 1609, this is the oldest extant palace gate in Seoul. Moving on, Changdeokgung’s suitably impressive throne room is without doubt the most regal-looking of any Seoul palace – light from outside is filtered through paper doors and windows, bathing in a dim glow the elaborate wooden beam structure, as well as the throne and its folding-screen backdrop. Beyond here are a number of buildings pertaining to the various kings who occupied the palace, some of which still have the original furniture inside. One building even contains some of the vintage cars beloved of King Sunjong, the Daimler and Cadillac looking more than a little incongruous in their palatial setting. Further on you’ll come to Nakseonjae, built during the reign of King Heonjong. The building’s Qing-style latticed doors and arched pavilion reveal his taste for foreign cultures, and without the paint and decoration typical of Korean palace buildings, the colours of the bare wood are ignited with shades of gold and honey during sunset.

The palace’s undoubted highlight is Huwon (후원), most popularly known as The Secret Garden. Approached via a suitably mysterious path, it is concealed by an arch of leaves and has a lotus pond at its centre. One of Seoul’s most photographed sights, the pond comes alive with colourful flowers in late June or early July. A small building overlooking the pond served as a library and study room in imperial times, and the tiny gates blocking the entrance path were used as an interesting checking mechanism by the king – needing to crouch to pass through, he’d be reminded of his duty to be humble.