Markets produce goods and services, but not all markets are the same. The way in which firms within the same market interact and behave is usually a function of how many firms there are in that market, the type of products that are being produced, and how easy it is for new firms to enter the market. This chapter provides the beginnings of a framework for several theories of market structures by reintroducing the most competitive market structure, that of perfect competition.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. List and explain the key assumptions of perfect competition.

2. Understand the difference between accounting and economic profit.

3. Use the rule for profit maximization to show how much output a perfectly competitive firm will produce.

4. Draw side-by-side graphs of a competitive market and the typical perfectly competitive firm to show the price, output, and short-run economic profit (or loss) earned by the firm.

5. Describe the conditions under which a firm will choose to shut down in the short run.

6. Show how the market adjusts to long-run equilibrium and how this long-run equilibrium outcome is both allocatively and productively efficient.

Economists typically recognize several assumptions of the theory of perfect competition that together have important implications for profitability and efficiency. Although real-world markets do not often resemble perfect competition, the outcomes of this market structure provide nice benchmarks by which other markets can be measured and evaluated. The key assumptions are:

• There are many buyers and sellers.

• Firms sell a homogeneous (identical) good.

• Firms (and consumers) can easily enter and exit the market.

• Firms and consumers have perfect information.

We also assume, until later chapters, that externalities do not exist in these markets. This simply means that there is no impact on third parties when goods are exchanged in the market. Chapter 6 described a critical implication of the perfectly competitive assumptions: neither a firm nor a consumer can affect the market price through individual actions. In other words, both firms and consumers are “price takers.” The market, through the forces of supply and demand, determines the price of the good, and firms and consumers take that price and make the best possible decisions given that price.

The assumptions about a perfectly competitive market give us some insight into why this is the case. Suppose a single seller of a good decides that she does not like the market price and charges a slightly higher price. Consumers who have perfect information and can buy an identical good from one of the many other sellers simply will not buy her good, and she will be forced to return to the market price. Similarly, since there are many buyers of the good, she can sell however many of the good she wants to at the market price, so if she lowers her price, all she will do is make herself worse off. (We will see in later chapters that when some of these assumptions change, firms do have some control over the price they charge.)

For the firms, this means that they must choose a level of output that will maximize profit at the market price. Before we go further into the theory of perfect competition, let’s briefly discuss economic profit and how it is maximized.

In Chapter 4 we discussed the costs of a firm and how they were broken down. Total costs of production are a function of output, and TC(Q) can be separated into two parts:

where TFC are the fixed costs that do not change as more or less is produced (and therefore TFC is not a function of Q), and TVC(Q) are the variable costs, which do change as more or less is produced.

Profit is the difference between the amount of money that a firm takes in (known as total revenue) and the amount that it costs the firm to produce what it sells. Total revenue (TR) is equal to the product of the quantity (Q) of units sold and the price (P) at which they were sold. Mathematically,

Mathematically speaking, then, the amount of economic profit (Π) that a firm makes from producing Q units is found in this manner:

Recall that in Chapter 4, we also found the marginal cost of production, MC(Q), which was the additional amount it cost the firm to produce the Qth unit of output (for example, if we were finding MC(4), this would be the additional amount it would cost to produce the fourth unit). We are also interested in the marginal revenue, or MR(Q), which is the additional revenue received from producing one more unit of input. MR(Q) can be found using the following formula:

Note that when we are talking about one more unit, the change in quantity is equal to 1. For instance, if a firm earns $500 from producing 10 units and $530 from producing 11 units,  .

.

In Chapter 1, we saw that an individual’s objective is to maximize utility, which she did when she found the quantity where  . The objective of a firm is to maximize profits. To the firm, the benefit of increasing production is to increase its revenue, but increasing production will also increase costs. A firm will increase production only as long as the additional cost incurred isn’t greater than the additional revenue received. In other words, a firm will be best off if it produces the quantity where

. The objective of a firm is to maximize profits. To the firm, the benefit of increasing production is to increase its revenue, but increasing production will also increase costs. A firm will increase production only as long as the additional cost incurred isn’t greater than the additional revenue received. In other words, a firm will be best off if it produces the quantity where

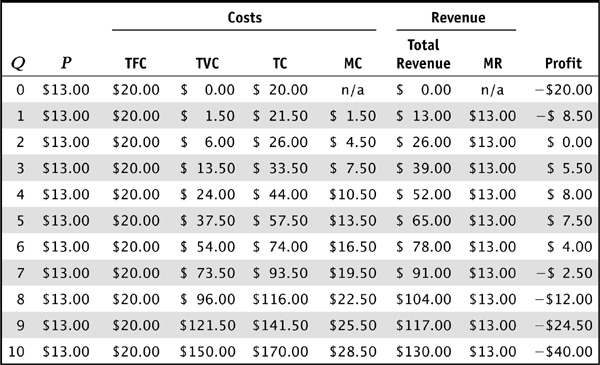

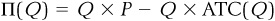

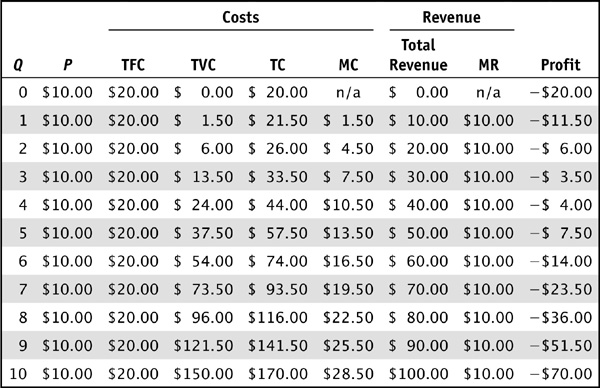

It may be helpful to see how this works using actual numbers. Suppose that Dave operates a landscaping service. Each week he has a fixed cost of $20 for a contract he has with an advertising agency to advertise his services. He has figured out that his costs vary based on the number of lawns he mows, and this varies according to the function  . The going rate for having your lawn mowed in his town is $13, which he will get regardless of how many lawns he mows. He wants to figure out how many lawns to mow to make the most profit. He enters the information in a spreadsheet (see Table 7-1).

. The going rate for having your lawn mowed in his town is $13, which he will get regardless of how many lawns he mows. He wants to figure out how many lawns to mow to make the most profit. He enters the information in a spreadsheet (see Table 7-1).

TABLE 7-1 Dave’s Costs, Revenue, and Profit at $13

As we can see, when he produces 4 units, he makes a profit of $8. No other quantity will give him a higher profit.

Laying out the numbers like this allows us to make some observations.

1. When the price doesn’t change, the marginal revenue doesn’t change.

2. The marginal cost, however, does change. In fact, his marginal cost increases.

3. At his profit-maximizing quantity of 4,  (or as close to it as you can get). This is always true mathematically, and it is sometimes called the profit-maximizing rule.

(or as close to it as you can get). This is always true mathematically, and it is sometimes called the profit-maximizing rule.

4. This profit-maximizing rule makes sense intuitively as well. Suppose Dave considers mowing 5 lawns instead of 4. He will get only $13 for mowing the fifth lawn, but mowing one more lawn will cost him $13.50.

Computing a firm’s profit is rather simple: begin with the total revenue earned from sales and subtract the total production costs. Despite this apparent simplicity of computing profit, accountants and economists have different views about what should be included in the total costs that are subtracted. Accountants, and the general public, include only the direct explicit costs made to employ production inputs supplied by people outside the firm. For example, most firms employ workers, and the paychecks written to those workers are an explicit cost of production. The same is true of payments made for raw materials, energy, machinery, interest on debt, rent on office space, and other such expenses. When all of the explicit (or accounting) costs are subtracted from total revenue, we have accounting profit as

Accounting profit = total revenue – explicit production costs

Economists agree that these payments are production costs, but they also understand that any time a decision is made, such as the decision to operate a firm, opportunity costs exist. For example, if the owner of Firm A could have earned a salary as an employee of Firm B, the owner has forgone this salary in order to operate his own firm. The forgone salary is an opportunity, or implicit, cost for this firm and should be included with the accounting costs in the calculation of total economic profit:

Economic profit = total revenue – (explicit production costs + implicit costs)

= TR − TC

If economic profit is greater than zero, the owner of the firm has earned enough revenue to pay all of the explicit production costs and all of the things that he gave up in order to pursue this venture. The goal of the firm is to produce the level of output that maximizes economic profit.

Since economic profit is simply the difference between total revenue and total economic cost, the firm must simply find the level of output where that difference is the greatest. Graphically, we saw the short-run total cost curve in Chapter 4, and it is reproduced in Figure 7-1. Because firms are price takers, total revenue is a straight line with a slope equal to the market-determined price. Economic profit (Π) or loss is the vertical distance between the total revenue line and the total cost curve. The graph shows two levels of output, Q1 and Q2, where total revenue is equal to total cost and thus economic profit is equal to zero. Below Q1 and above Q2, total cost exceeds total revenue, and economic losses are incurred. Between Q1 and Q2, economic profit is positive, and at Q*, the economic profit is maximized.

FIGURE 7-1 • Economic Profit

There’s actually an equivalent way to find the profit-maximizing output that will prove to be more useful as we analyze how firms behave: compare the marginal revenue of the next unit sold to the marginal cost of producing that unit. Recall that marginal is synonymous with “additional,” so if the additional dollars coming into the firm from the next unit are at least as great as the additional dollars leaving the firm, the firm profits from producing the next unit.

We can see the profit-maximizing output Q* in Figure 7-2 at the intersection of the upward-sloping marginal cost (MC) curve and the horizontal marginal revenue (MR) curve. When firms are price takers, the additional revenue from selling the next unit is simply the market price (P). Because the firm cannot affect the market price by producing fewer or additional units of output, and because we assume that all units produced are sold at that price, the marginal revenue curve also serves as the demand curve (D) for this perfectly competitive firm’s product. In the next section of the chapter, we discuss how we can determine how much economic profit the firm is earning and whether the firm should produce anything in the short run.

FIGURE 7-2 • Marginal Revenue and Marginal Cost

A perfectly competitive firm can earn positive economic profit if the market price is high enough so that the total revenue is greater than the total economic cost. Alternatively, on a per-unit basis, profit is positive if the price per unit is greater than the total cost per unit. Recall from Chapter 4 that we had a special term for cost per unit: average total cost, or  . Multiplying per-unit profit by the units produced gets us back to total profit. This is seen by manipulating the earlier equation for total profit (Π):

. Multiplying per-unit profit by the units produced gets us back to total profit. This is seen by manipulating the earlier equation for total profit (Π):

Recall that  . If we rearrange this by bringing Q to the left side of the equation, we get

. If we rearrange this by bringing Q to the left side of the equation, we get  , which we can then substitute into our profit function:

, which we can then substitute into our profit function:

Note that there is a common variable, Q. Let’s pull the Q out to group terms:

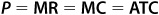

In order to show the profit or loss being earned, it is useful to draw two graphs side by side. The graph on the left, Figure 7-3, shows the market for a perfectly competitive product like wheat. The graph on the right, Figure 7-4, shows, for a typical wheat farmer, the marginal cost (MC), average variable cost (AVC), average total cost (ATC), and marginal revenue (MR) curves. To maximize profit, the firm takes the market price Pc and finds the output Qf where  . At that output, the price is greater than average total cost, so profit per unit is positive. The area of the shaded “profit rectangle” represents the positive economic profit.

. At that output, the price is greater than average total cost, so profit per unit is positive. The area of the shaded “profit rectangle” represents the positive economic profit.

FIGURE 7-3 • Market Price and Quantity for a Competitive Product

FIGURE 7-4 • Price and Quantity for a Single Firm with Economic Profits

We must keep in mind that all firms in the perfectly competitive wheat industry are earning positive short-run economic profit because the market price happens to be greater than average total cost. Suppose that the market price were significantly lower. Figure 7-6 shows a wheat producer that finds the profit-maximizing output where P = MR = MC, but, because the market price of wheat has fallen below average total cost, economic profit is negative. The losses are again seen as the area of the shaded rectangle in the graph. The corresponding graph for the market is shown in Figure 7-5.

FIGURE 7-5 • Market Price and Output for a Competitive Product

FIGURE 7-6 • Price and Quantity for a Single Firm with Economic Losses

If all of the wheat farmers are incurring losses in the short run, why are they still in business? The reason is that the farmers are losing less money by operating at a loss than they would lose if they ceased production altogether. Recall that we are discussing the short-run production period, and in the short run, fixed costs exist. The producers must pay the fixed cost no matter what the level of output, even if that output is zero. Because fixed costs always must be paid, the relevant production decision really boils down to whether the variable costs can be paid. If the price is high enough so that total revenue exceeds total variable cost, the firm minimizes its losses by producing at the point where  . On a per-unit basis, if the price is greater than or equal to the average variable cost, the firm should continue to produce in the short run, even at a loss. This is known as the shutdown decision: if

. On a per-unit basis, if the price is greater than or equal to the average variable cost, the firm should continue to produce in the short run, even at a loss. This is known as the shutdown decision: if  , then the firm should choose

, then the firm should choose  . The firm in Figure 7-6 is minimizing short-run losses by producing Qf units of output because the market price is greater than average variable cost. If the price were to fall below the minimum of average variable cost, the firm would shut down, producing zero units in the short run, and lose only the total fixed costs that must always be paid. If the price does not soon rise, many of these firms will cease to exist in the long run.

. The firm in Figure 7-6 is minimizing short-run losses by producing Qf units of output because the market price is greater than average variable cost. If the price were to fall below the minimum of average variable cost, the firm would shut down, producing zero units in the short run, and lose only the total fixed costs that must always be paid. If the price does not soon rise, many of these firms will cease to exist in the long run.

To see why this is, consider Dave’s production decision again. Suppose the market price of lawn service fell to $10. Now his spreadsheet looks like Table 7-2.

TABLE 7-2 Dave’s Costs, Revenue, and Profit at $10

Dave has to face an unhappy fact: there is no way he will make a profit at a price of $10. Should he not mow any lawns? Well, he still has a contract with the ad agency, so he has to pay $20 to it no matter what. If he produces nothing, he is producing Q = 0, which would give him a profit of −$20. If, on the other hand, he produces 3 units, he loses only −$3.50, which isn’t as bad. So in the short run, at least until the contract expires, he will continue to produce.

It’s not always easy to understand the shutdown decision. As with most things in economics, try to think about it as another example of how we weigh the benefits and costs of any decision. The decision is whether to produce Qf units of output in the short run. Two things happen when Qf units are produced:

1. The firm receives total revenue (TR) from the sale of those units.

2. The firm incurs total variable cost (TVC) from the production of those units.

Now the decision is easy:

• If  , those units should not be produced.

, those units should not be produced.

On a per-unit basis, the decision becomes:

• If  , those units should not be produced.

, those units should not be produced.

We have seen that perfectly competitive firms can earn either positive or negative short-run profits, but a key assumption guarantees that these profits will not last. With free entry of new firms and easy exit of existing firms, long-run profits will be driven to zero. Let’s see how this works. Again suppose that producers in the wheat market are earning short-run positive economic profits. In the long run, with enough time to mobilize the necessary land, labor, and capital, new wheat farmers will emerge and begin to produce wheat. As more producers offer wheat to the market, the market supply curve shifts to the right. And as the supply curve shifts to the right, the price begins to fall, each producer produces less, and the rectangle of profit shrinks. When will the last new firm enter the market? When the price is reduced to where it equals average total cost and economic profit is equal to zero.

Figures 7-7 and 7-8 show how the market, and the firm, will adjust from short-run economic profits to the long-run equilibrium. Through the entry of new firms, the short-run price of PSR has been driven downward to the long-run price PLR, which intersects the marginal cost curve at the minimum of the average total cost curve. More total output is being produced in the market, but each firm produces fewer units in the long run than it did when the short-run price was higher.

FIGURE 7-7 • Perfectly Competitive Market Adjusting to Short-Run Profits

FIGURE 7-8 • Long-Run Equilibrium for Perfectly Competitive Firm

A similar adjustment takes place when short-run losses are incurred. In the long run, some firms will exit the wheat market. When there are fewer producers, the supply curve shifts to the left, and the market price begins to rise. As the price rises, each firm produces more wheat and the rectangle of losses gets smaller. The exit of firms ends when the losses are eliminated and all remaining firms are breaking even. The long-run price, whether there were short-run profits or losses, is always the same and is the price that is equal to average total cost.

We discussed the efficiency of competitive markets in Chapter 6, but the long-run outcome for perfectly competitive firms allows an opportunity to provide a little more detail. Economists see two important sources of efficiency in this model: allocative and productive efficiency. Allocative efficiency is achieved because each firm is producing the level of output at which price is equal to marginal cost. By producing this quantity, the firm is producing neither too much nor too little. Because each firm is producing the efficient output where price equals marginal cost, the market produces the “right” level of output where supply intersects demand. In other words, in perfect competition, there is no deadweight loss. Firms also achieve productive efficiency. The long-run equilibrium ensures that each firm produces at the level where the average total cost is minimized. If there were firms that could not produce the same product, sold at the same market price, for the minimum average total cost, they would be forced to exit the market. Thus each remaining firm must be as productively efficient as possible. We soon discover that, when the market structure turns from competitive to monopolistic, these efficiencies cease to exist.

This chapter introduced the model of perfect competition, the key assumptions of that model, and the difference between accounting and economic profit. Firms maximize profit by finding the level of output where the marginal revenue of the next unit sold (which is equal to the price in this model) is equal to the marginal cost of producing it. If the price is greater than average total cost, short-run economic profits will be made. If the price is less than average total cost, short-run economic losses will be incurred. However, the firm will shut down in the short run if the price falls below average variable cost. In the long run, entry and exit of firms will return economic profits to the breakeven level and long-run equilibrium. In this equilibrium, the market and the firm achieve both allocative and productive efficiency. We see in the next chapter that the model of monopoly has very little in common with the outcomes seen in perfect competition.

Is each of the following statements true or false? Explain.

1. If economic profit is equal to zero, accounting profit is positive.

2. If the price is less than the average total cost, the firm must shut down in the short run.

3. A key assumption of perfect competition is that firms can set the price.

4. In the long run, the following is true:  .

.

For each of the following, choose the answer that best fits.

5. Which of the following is an accurate statement about perfect competition?

A. In the long run, the price is equal to average variable cost.

B. There are no barriers to entry or exit.

C. Firms can increase the price to increase profits.

D. Price is greater than marginal revenue in the short run, but equal to marginal revenue in the long run.

6. Suppose firms in a perfectly competitive market are earning positive short-run economic profits. Which of the following statements is accurate?

A. Long-run profits in this market will be positive.

B. In the long run, exit of firms will increase profits to zero.

C. In the long run, entry of firms will decrease profits to zero.

D. Long-run profits in this market will be negative.

7. Josie is a perfectly competitive soybean farmer who is currently producing 100 bushels at the market price of $50 per bushel. Her average variable cost is $60, and her average fixed cost is $10 per bushel. If Josie wants to increase her short-run profit, she should:

A. Shut down and produce nothing.

B. Continue to produce 100 bushels.

C. Increase the price to $70 per bushel.

D. Increase her output.

Use the graph in Figure 7-9 for questions 8 to 10.

FIGURE 7-9

8. Using the labels in the graph, if the current price in the market is P1, the firm will produce _____ units of output and short-run profits will be _____.

A. Q4; zero

B. Q1; negative

C. Q3; zero

D. Q4; positive

9. If the short-run price is P3, the long-run price will be:

A. P1

B. P2

C. P3

D. P4

10. Which of the following prices would cause the firm to shut down in the short run?

A. P2

B. P3

C. Any price between P2 and P4