Perfect competition is the most competitive of market structures, and monopoly is the least competitive. Because firms in perfect competition can only hope to break even in the long run, most of them probably would rather be monopolists, who can earn profits in the long run. As we shall see, the long-run market equilibrium for the monopolist is quite different from the outcome in the perfectly competitive market.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. List and explain the key assumptions of monopoly.

2. Understand the relationship between the price of a unit sold, the marginal revenue received from its sale, and the price elasticity of demand along the demand curve.

3. Use the rule for profit maximization to show how much output a monopoly firm will produce.

4. Use a graph to show the monopolist’s output, the price it sets, and the area of profit it earns.

5. Describe how the monopoly outcome creates deadweight loss.

6. Discuss how government can regulate a natural monopolist and the pros and cons of doing so.

7. Understand price discrimination in general and one type, perfect price discrimination, in particular.

The goal of the board game Monopoly is to have only a single winner. Similarly, the assumptions of the monopoly market structure begin with the premise that there will be only one “winner.” A market is deemed a monopoly if it is characterized by the following:

• Only one firm is selling a good to many consumers.

• The product has no close substitutes.

• A barrier to entry of new firms exists.

The absence of close competitors and substitute products creates a situation in which the monopolist is a “price maker” rather than a market “price taker.” The ability to set the price leads to long-run economic profits and can sometimes invite regulation by the government. For now, we will also assume that the firm sets only one price to maximize profit, but there are situations in which firms with monopoly power have the ability to set different prices for different groups of consumers. We look at both regulation and price discrimination later in the chapter.

When we discussed the perfectly competitive market for wheat, we recognized that there were two demand curves: the downward-sloping market demand for wheat and the perfectly elastic (horizontal) demand curve for each farmer’s wheat. The horizontal demand curve was equal to the market price because each farmer was a price-taking seller. Under the assumptions of monopoly, there is only one firm selling a product with no close substitutes. This implies that the demand for the firm’s product is the same as the market demand for the product.

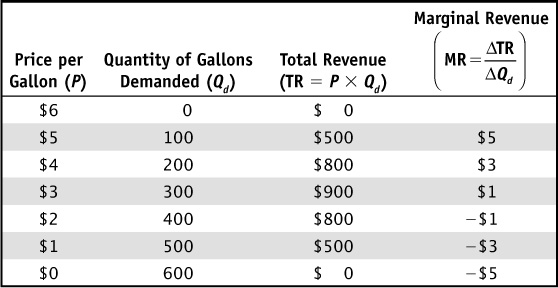

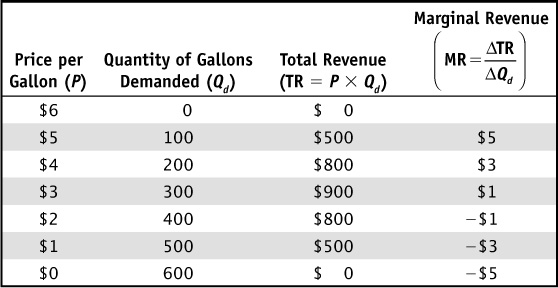

Suppose that on a lonely stretch of rural highway, there is only one gas station for miles in all directions. Table 8-1 provides the demand schedule for this monopoly seller of gasoline. The table also includes a column that calculates the total revenue earned by the monopolist at each price and the marginal revenue from selling each additional hundred gallons of gas. Recall that marginal revenue is the change in total revenue divided by the change in the quantity of units sold. A couple of things are clear from the table. First, total revenue rises until 300 gallons have been sold, but then falls as more gallons of gasoline are sold. Second, with the exception of the first 100 gallons sold, the marginal revenue of the last gallon sold is less than the price at which it was sold. We will show that these two results are related.

TABLE 8-1 Demand Schedule for Monopoly Seller

Why does total revenue not continue to increase as more gallons of gasoline are purchased? It’s because the monopolist must lower the price to sell those additional gallons of gas. Recall the simple definition of total revenue:

In Chapter 3, when discussing the price elasticity of demand, we described how lower prices have two competing impacts upon total revenue. These are referred to as the price effect and the quantity effect:

• Price effect. After a price decrease, each unit sold sells at a lower price, which tends to decrease revenue.

• Quantity effect. After a price decrease, more units are sold, which tends to increase revenue.

Between zero and 300 gallons of gasoline, lower prices cause total revenue to rise. It must be the case that in this portion of the demand curve the quantity effect is stronger than the price effect, and this can happen only when demand is price-elastic. Beyond 300 gallons of gasoline, lower prices cause total revenue to decrease. This can happen only when demand is price-inelastic. When demand schedules are linear, like the one depicted in Table 8-1, the upper half of the demand curve is price-elastic and the lower half is price-inelastic. Total revenue along the demand curve will be maximized at the midpoint. Figure 8-1a shows the demand curve from the data in Table 8-1, and Figure 8-1b shows the total revenue curve associated with the demand. A marginal revenue curve is also added to Figure 8-1a, and we now turn to the relationship between marginal revenue and price. (You might notice that the marginal revenue curve does not exactly match the data from the table. For a more mathematical explanation of the relationship between marginal revenue, total revenue, and the demand curve, we invite you to peruse the appendix to this chapter.)

FIGURE 8-1 • Demand, Marginal Revenue, and Total Revenue for a Monopolist

But why does the marginal revenue curve lie below the demand curve? In other words, why is price always greater than marginal revenue for the next unit sold? The relationship between price and marginal revenue is caused by the pricing behavior of the monopolist. When the monopolist wants to sell additional units, he must lower the price not just for the next one unit, but for all the units sold. For instance, the monopolist cannot sell the first 100 units at $4 and the next 100 units at $3. If he wants to sell 200 units, he must charge the lower price for all of them. While revenue is gained on the additional units, some revenue from the previous units is lost because of the lower price.

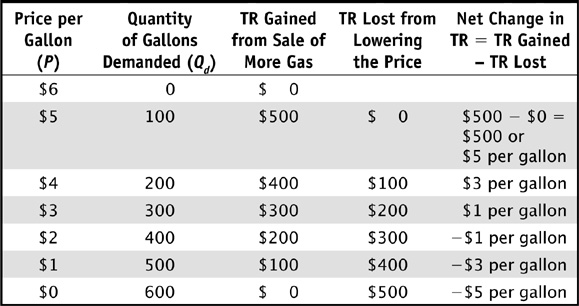

Another simple graphical example can help show how this works. Figure 8-2 replicates the demand curve for gasoline but omits the marginal revenue curve. At a price of $5, 100 gallons are sold, and the area of total revenue ($500) is seen as the tall shaded rectangle. Now suppose the monopolist wishes to sell 200 gallons. He must lower the price to $4 to sell this quantity. This earns the monopolist $400 of additional revenue, and this is shown as a slightly smaller rectangle. However, he must also lower the price by $1 for the first 100 gallons, and this costs him $100 of revenue. The net gain from lowering the price to $4 is $300 per 100 gallons, or $3 per gallon. In a similar way, the price of the next unit of a good will always exceed the marginal revenue earned from selling that unit.

FIGURE 8-2 • Effects of Price Decreases on Revenues

It’s not easy to understand why marginal revenue is less than price and lies below the demand curve. Let’s revise Table 8-1 by adding columns to show where the total revenue (TR) is lost and gained when the price falls along the demand curve for gasoline (see Table 8-2). When we subtract the lost revenue from the gained revenue, we can see whether total revenue will rise or fall.

TABLE 8-2 Monopolist’s Loss and Gain of Total Revenue

Table 8-2 shows that the quantity effect that increases total revenue gets smaller and smaller as more gasoline is added, but the price effect that decreases total revenue gets larger and larger as the price falls. Once the price falls below $3, total revenue actually falls and marginal revenue becomes negative.

On a more intuitive level, think about what marginal revenue actually is: the additional revenue that a firm gets from selling one more unit. Consider if a firm raises its price to $3. The marginal revenue is the additional amount of money that the firm will put in its cash register. When people incorrectly state that marginal revenue is greater than the price (or above the demand curve), they are basically saying that the firm charged $3, but somehow more than that amount made it into the cash register. This is clearly impossible.

Any firm, whether it is perfectly competitive or a monopolist, maximizes profit in the same way: by setting marginal revenue equal to marginal cost. For all types of firms, we expect the marginal cost to be upward-sloping. As discussed in the previous section, we expect the monopolist’s marginal revenue to be downward-sloping and below the demand curve. The monopolist’s profit-maximizing decision is shown in Figure 8-3, and the output that maximizes profit is Qm. The price Pm that is necessary to sell Qm units is found from the demand curve, and, because the average total cost curve lies below Pm, a rectangle of economic profit is shaded. These economic profits are likely to last into the long run because new entrants are faced with significant barriers to entry. The area of consumer surplus has also been shown as the area under the demand curve and above Pm.

FIGURE 8-3 • Monopolist’s Profit-Maximizing Decision

The efficiency of perfect competition was discussed in Chapter 7. Perfectly competitive firms and markets are allocatively efficient because output is produced at the level where marginal cost is equal to the price. At this quantity, neither too much nor too little is being produced. In Figure 8-4, we see that at Qm, the price Pm is greater than marginal cost.

FIGURE 8-4 • Deadweight Loss from Monopoly

From society’s point of view, producing one more unit is beneficial so long as price exceeds marginal cost, because total surplus will rise. In fact, society would maximize total surplus under perfectly competitive conditions if output were increased to the point where the marginal cost curve intersects demand at the output of Qe. If that efficient level of output were to be produced, the price would be much lower at Pe, and consumers would certainly be better off because there would be a larger area of consumer surplus. From the monopolist’s perspective, however, producing one more unit would decrease profit, and so that unit will not be produced. Because the units between Qm and Qe will not be produced, deadweight loss exists as the area below demand and above marginal cost.

The monopolist is also not producing the output that provides technical efficiency, as average total cost is not minimized at Qm. Because of these inefficiencies, and because the monopoly price exceeds the competitive price, monopolies have frequently been the target of government regulation. This is the topic of the next section.

We have seen a couple of monopoly outcomes that can be problematic. First, the absence of competition allows the monopolist to reduce output below the competitive output and increase the price above the competitive price. This outcome reduces consumer surplus and creates inefficiencies. The monopolist also earns long-run economic profit, which further reduces consumer surplus, and this could raise issues of equity. After all, some people become concerned when the consumer surplus enjoyed by many households is transferred to a single entity (the monopolist).

Regulation becomes important to government when the monopolist is producing something that is critical to society, like electricity or other public utilities. In fact, economists refer to these firms as natural monopolies. A natural monopoly exists when a very large firm, such as an electric company, has such vast economies of scale that electricity can be produced at the lowest possible average total cost when there is one producer of electricity rather than several smaller producers.

We can address two broad goals for regulating a monopolist such as a public utility: regulate to the efficient level of output, or regulate so that economic profit is equal to zero. Figure 8-5 shows both regulatory options. The unregulated monopolist is still producing Qm, where marginal revenue equals marginal cost, and setting the monopoly price of Pm. To regulate the monopolist to produce the efficient level of output, the output must be at Qe, where marginal cost equals price. This level of output would eliminate deadweight loss, but it might also cause the firm to incur losses, as the price Pe may actually lie below average total cost. To avoid this outcome, the government may instead choose to regulate the firm in a way that causes the firm to earn zero economic profit. This occurs at the output Q0, where the price P0 is equal to average total cost. Some dead-weight loss would exist, but not as much as would exist if the monopolist were unregulated. Neither regulatory option is perfect, but the latter has advantages in that it allows the firm to earn a fair rate of return, lessens the inefficiency, and lowers prices to the consumer.

FIGURE 8-5 • Effects of Different Methods of Government Regulation of Monopolies

So far, we have assumed that the monopolist sets only one price, the one associated with selling the profit-maximizing level of output. But sometimes there are opportunities to increase profit by selling the same product to different groups of consumers and charging different prices to those different groups. This behavior is known as price discrimination, and we are familiar with several common examples. Suppose that Becky takes her grandfather to see the latest Harry Potter movie. When Becky’s ticket costs $9 and her grandfather’s costs $7, the theater is engaging in price discrimination. Suppose that Dorothy buys a plane ticket from Portland to San Francisco a month in advance of the flight, and Ray buys a ticket for the same flight two hours prior to takeoff. If Ray and Dorothy compared receipts, they would discover that Ray paid much more for the same flight. In both of these situations, the seller has charged different prices to different persons for the same product.

How is this possible? Each firm knows that it can increase its profit by doing so, and each must have three important characteristics to make it work. First, each seller must have some monopoly ability to set the price. Second, the seller must be able to differentiate the two consumers. The theater knows that Becky is not a senior citizen, and the airline knows that Ray has waited until the last minute to buy his ticket. Finally, the sellers must be able to prevent resale of the good. If Becky’s grandfather could buy senior tickets and resell them in the parking lot to Becky’s friends for a tidy profit, the theater’s pricing strategy would fall apart.

The real differentiating characteristic that allows price discrimination to exist is that each group of consumers has a different price elasticity of demand for the good. Take the Dorothy and Ray example. The airline offers Ray a very high price for the last-minute ticket because it knows that Ray has a very low price elasticity of demand and that he has no choice but to pay the high price. He may be a business traveler who has suddenly discovered a very important reason to be in San Francisco, whereas Dorothy is traveling for pleasure and could afford to shop around and buy her ticket well in advance. In any price discrimination strategy, the group with the more elastic demand curve will pay a lower price than the group with the least elastic demand curve for the same good.

A special kind of price discrimination is known as perfect price discrimination. In this hypothetical situation, each consumer is charged the maximum price that she is willing to pay. Figure 8-6 shows this situation. The person represented at the top of the demand curve is charged the very highest price P1 because he will pay it; the next person is charged a slightly lower price, and so on until the last person is charged the price Pe that equals the firm’s marginal cost. When this happens, the demand curve is also the marginal revenue curve. Because each person is charged exactly the maximum price that she would pay, total consumer surplus is equal to zero. All the surplus goes to the monopolist. Ironically, while this sounds unfair to each individual consumer, it provides the efficient level of output to society because price is equal to marginal cost and no deadweight loss exists.

FIGURE 8-6 • Perfect Price Discrimination

This chapter introduced the model of monopoly, the key assumptions of that model, and how it greatly differs from perfect competition. A monopolist sets the price at the output where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. Unlike firms in perfect competition, marginal revenue declines as more output is sold and is always less than the price at which the output is sold. Because barriers to entry exist, monopoly profits can last in the long run, yet because monopolists reduce output below the level where price equals marginal cost, dead-weight loss emerges. Because monopolies create both positive profits and deadweight loss they are often the targets of government regulation designed to lower the price and increase efficiency. Some firms with monopoly power also engage in price discrimination by charging two groups of consumers different prices for the same products. By doing this, these firms are able to increase profit, and reduce consumer surplus, even more than a single-price monopolist. In the next chapter we will discuss two market structures that fall between the two extreme cases of perfect competition and monopoly.

When demand is linear, there is a very clear relationship between the demand curve and the marginal revenue curve. Let’s use a simple example to illustrate. (Warning: a little calculus is required.)

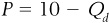

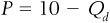

Suppose demand is linear and is given as:

This demand function is indeed a straight line with a y intercept of 10 and a slope of − 1, and it is shown in Figure 8-7. The marginal revenue is also included in the graph, but to get that marginal revenue function, we must first develop the total revenue function.

FIGURE 8-7 • Demand and Marginal Revenue Curves

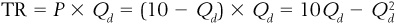

Total revenue is price multiplied by quantity demanded, so with the demand function just given, we get the following total revenue function:

Notice that this is a quadratic function; it is depicted in Figure 8-8.

FIGURE 8-8 • The Total Revenue Curve When Demand Is Represented by

Figure 8-8 shows that total revenue is maximized at a quantity of 5 units and that total revenue is equal to $25 at that quantity. How do we know this? In order to maximize a function, we need to take the first derivative, set it equal to zero, and solve for quantity. Why do we take this approach? The first derivative gives us the slope of the function, and the slope of the total revenue function is equal to zero at the point where it is maximized. The slope of the function is also marginal revenue, so total revenue is maximized when marginal revenue is equal to zero.

If we set marginal revenue equal to zero and solve for Qd, we can clearly see that a quantity of 5 units maximizes total revenue.

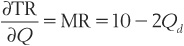

Finally, let’s look at the original demand equation side by side with the marginal revenue function.

Demand:

Marginal revenue:

Both functions are straight lines with a y intercept of 10; the only difference between these two functions is that the marginal revenue function has a slope of −2. In other words, the slope of the marginal revenue curve is twice as steep as the slope of the demand curve. And at any value of quantity demanded (except zero, of course), the marginal revenue will be less than the price. For example, at the midpoint quantity of 5 units, the price from the demand curve is $5, but the marginal revenue is zero. The results of this simple example can be generalized for any linear demand curve:

• The marginal revenue function lies below the demand function and is twice as steep.

• Total revenue is maximized at the quantity that serves as the midpoint of that demand curve.

Is each of the following statements true or false? Explain.

1. When compared to prices in perfectly competitive markets, monopoly prices are higher and fewer units are produced.

2. As with perfect competition, entry of new firms will cause short-run monopoly profits to fall to zero.

3. If the monopoly price is $8 at the profit-maximizing output, the marginal revenue is greater than $8.

4. If a natural monopoly is regulated in such a way that price equals average total cost, deadweight loss is eliminated.

For each of the following, choose the answer that best fits.

5. Which of the following statements is true of monopoly markets?

A. Barriers to entry exist in the short run, but not in the long run.

B. Price is greater than marginal revenue but less than marginal cost.

C. Demand is more elastic than the demand for a perfectly competitive firm’s output.

D. Demand for the firm’s product is also the market demand for the product.

6. Which of the following is not an example of price discrimination?

A. Joe rents a two-bedroom apartment, and Susan rents a three-bedroom apartment. Susan’s rent is higher than Joe’s.

B. Joe and Susan each buy a bottle of shampoo at the grocery store. Because Joe is a member of the store’s “super saver” club, he receives a discount, whereas Susan does not.

C. Joe and Susan each buy the same pancake breakfast at Denny’s. Because Joe is a senior citizen, he receives a discount on his pancakes, but Susan does not.

D. Joe and Susan are each planning a trip to Mexico. Susan buys her hotel and plane tickets together as a package and receives a discount. Joe buys the same hotel and plane tickets, but he buys them separately and pays a higher price.

7. Deadweight loss in a monopoly market is the result of:

A. Price exceeding marginal cost at the profit-maximizing monopoly output

B. Price equaling marginal cost at the profit-maximizing monopoly output

C. Price equaling average total cost at the profit-maximizing monopoly output

D. Marginal cost exceeding price at the profit-maximizing monopoly output

Give a short answer to the following questions.

8. Draw a graph showing a profit-maximizing monopolist earning positive economic profit. In the graph, label the following:

• The monopoly output Qm

• The monopoly price Pm

• The area of monopoly profit

• The area of consumer surplus

• The area of deadweight loss

9. Referring back to the monopolist in problem 8, suppose the government taxed the monopoly profit and gave it back to the consumers as a refund. How would this affect the level of deadweight loss in the monopoly market?

10. Table 8-3 shows the demand schedule for a monopolist. Complete the total revenue and marginal revenue columns of the table. If the marginal cost and average cost are a constant $5, how much output will be produced, what price will be charged, and how much profit will be earned?