So far, much of this book has focused on the U.S. economy, but clearly American consumers and American firms buy and sell in the global economy. Consumers enjoy buying products made in other nations, and firms enjoy selling to foreign customers. This chapter explores the concept of comparative advantage and mutually beneficial trade and how trade is facilitated by the foreign currency markets.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. Use the production possibilities model to show a nation’s capacity to produce two goods and how the production possibilities curve (PPC) can be used to determine comparative advantage in production.

2. Understand how two nations benefit from trade if trade is based on comparative advantage.

3. Use the foreign exchange markets to show how currencies appreciate and depreciate with the flow of trade and with the impact of fiscal and monetary policy, and how this affects the AD-AS model.

4. Understand a nation’s balance of payments accounts and how they are affected by trade.

5. Describe how a tariff or quota distorts markets and creates inefficiencies.

Economists use a very simple representation of production known as the production possibilities model to demonstrate several important concepts, such as scarcity, opportunity cost, economic growth, and the benefits of trade between nations. We begin with two simple assumptions:

• A nation produces only two goods.

• Resources (labor, capital, land, and entrepreneurial talent) and technology are fixed.

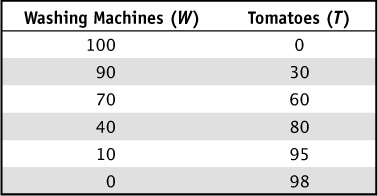

Suppose the nation of Elijastan produces only two goods, washing machines and tomatoes. Table 17-1 shows the nation’s production possibilities, meaning all the different combinations of washing machines and tomatoes that it can produce given its current stock of resources and technology.

TABLE 17-1 Elijastan Production Possibilities

Table 17.1 shows that as more tomatoes are produced, fewer washing machines can be produced with the same amount of resources. The data in the table can be converted to a graph, and the downward-sloping curve in Figure 17-1 is called the production possibilities curve (PPC).

FIGURE 17-1 • Elijastan Production Possibilities

Note that the PPC is downward-sloping. This is because, as reflected in the table, in order to produce more of one good, Elijastan must give up producing some of the other good. Not only is the PPC downward-sloping, but it gets steeper as more tomatoes are produced. The slope of the PPC also has an intuitive interpretation—the slope of the PPC represents the opportunity cost of producing tomatoes. For instance, if the nation moves from point A to point B, 30 tomatoes are gained, but 10 washing machines are lost. Thus the opportunity cost of just 1 tomato is  of a washing machine. However, when the nation moves from point E to point F, 3 tomatoes are gained at a cost of 10 washing machines. The opportunity cost of 1 tomato here is 3.33 washing machines. We can see that the opportunity cost of producing tomatoes rises as more are produced.

of a washing machine. However, when the nation moves from point E to point F, 3 tomatoes are gained at a cost of 10 washing machines. The opportunity cost of 1 tomato here is 3.33 washing machines. We can see that the opportunity cost of producing tomatoes rises as more are produced.

Why does this opportunity cost rise? It rises because a nation’s resources are not perfectly suited to the production of all things. Some land is great for tomatoes and some land is not. Some machines are great for heavy manufacturing but not so good for farming.

Remember that along the PPC, the resources of Elijastan are fully employed. Suppose that the nation is currently producing at point A, with zero resources devoted to tomatoes and all resources devoted to washing machines. If the nation wants to move to point B, resources need to be allocated to tomatoes and away from machines. Of course Elijastan should allocate the best agricultural resources to tomatoes, and if those resources are the best for agriculture, they are likely to be the worst for manufacturing. The gain in tomatoes is big, and the loss in machine production is small.

But when the nation gets to point E and wants to move to point F, all of the good agricultural resources have already been devoted to tomatoes, and only the best manufacturing resources remain producing washing machines. When the last move is made to point F, tomato production rises by an insignificant amount at a very high cost in lost washing machines.

A point like point G that lies inside the PPC represents a combination of washing machines and tomatoes that doesn’t use all the available resources. At this point, there are unemployed and idle resources, which might mean that there is a recession in Elijastan. A point like point H that lies beyond the PPC is a combination of goods that is currently unattainable. Economic growth could allow the nation’s production possibilities to expand.

Suppose that Elijastan develops better crop technology that allows it to grow 25 percent more tomatoes with the same quantity of resources. The new PPC shifts outward by 25 percent along the x axis, indicating that the nation’s production possibilities have expanded. This won’t help the nation produce washing machines, so the PPC still intersects the y axis at 100 machines.

FIGURE 17-2 • Elijastan Production Possibilities with New Technology

Now suppose that the nation of Elijastan has a neighboring nation, Maxigania, that can also manufacture washing machines (W) and grow tomatoes (T). To keep things slightly simpler, we will assume that the opportunity costs are constant, rather than increasing. This gives production possibility curves that are linear rather than concave. Figure 17-3 shows the PPCs for both nations side by side. Note: For the purposes of this example, the production possibilities of Elijastan are different from those in the earlier example.

FIGURE 17-3 • Production Possibilities for Elijastan and Maxigania

We can see that Elijastan can produce more washing machines and more tomatoes than Maxigania if it focuses all its resources on either of these two goods. In other words, if both countries devoted all of their resources to making washing machines, Elijastan would produce 100 units, but Maxigania would produce only 80, and if instead they devoted all of their resources to growing tomatoes, Elijastan would produce 100 units, but Maxigania would only produce 40. When one nation can produce more of any particular good than another nation, it is said to have an absolute advantage in the production of that good. In this case, Elijastan has an absolute advantage in both goods.

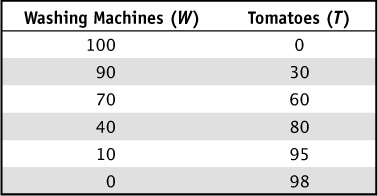

We also see that the slopes of the PPCs are different for the two nations. The slope of Elijastan’s PPC is 1 (we can ignore the negative sign), and the slope of Maxigania’s PPC is 2. Recall that the slope tells us the opportunity costs of producing the good graphed on the x axis. Table 17-2 shows the opportunity cost of producing tomatoes and washing machines for both nations.

TABLE 17-2 Opportunity Costs for Elijastan and Maxigania

Elijastan can produce tomatoes at a cost of one washing machine for each tomato. Maxigania can also produce tomatoes, but at a cost of two washing machines for each tomato. When a nation can produce a good at a lower opportunity cost than another nation, that nation is said to have a comparative advantage in that good. Elijastan has a comparative advantage in tomato production. Maxigania has a comparative advantage in the production of washing machines because each washing machine costs it only  of a tomato, while a washing machine costs Elijastan one full tomato.

of a tomato, while a washing machine costs Elijastan one full tomato.

Still Struggling

Still Struggling

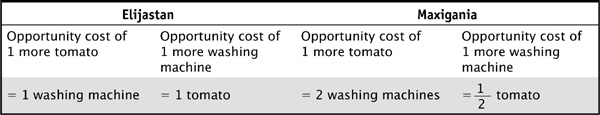

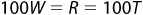

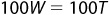

When we have linear PPCs, another way we can solve for opportunity cost is by using simple algebra. Let’s start with Elijastan. Using all its resources (R), it can produce 100 washing machines, so  . If it devotes all its resources to making tomatoes,

. If it devotes all its resources to making tomatoes,  . Note that:

. Note that:

We can simplify this to:

To find the opportunity cost of washing machines, we simply solve for W:

so each washing machine costs one tomato. To find the opportunity cost of tomatoes, we solve for T:

so each tomato costs one washing machine.

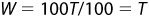

We can do the same for Maxigania:

so one washing machine costs  of a tomato. To find the opportunity cost of a tomato, we solve for T:

of a tomato. To find the opportunity cost of a tomato, we solve for T:

so one tomato costs two washing machines.

How is this information about opportunity costs and comparative advantage useful? Suppose that each nation is currently producing at the midpoint (points M) of its PPC. Figure 17-4 shows this point of production.

FIGURE 17-4 • Specialization and Gains from Trade

We have already seen that a nation’s economy can grow with technological progress, but in 1817 David Ricardo wrote in his book On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation that trade based upon specialization and comparative advantage can also allow a nation to consume beyond its PPC. To see how this works, we imagine that Elijastan specializes in producing tomatoes because it has a comparative advantage in that good. Maxigania specializes in producing washing machines because it has a comparative advantage in that good. These decisions to specialize are seen as points S in Figure 17-4.

The two specializing nations would then sit down to negotiate terms of trade that are mutually beneficial. Suppose we are trade representatives for Elijastan. Elijastan wants washing machines and can produce them without trade by giving up one tomato for each machine. If Elijastan is going to receive washing machines from Maxigania, each machine must cost less than one tomato or the deal doesn’t benefit Elijastan.

Maxigania must also find acceptable terms of trade. Maxigania wants tomatoes and can produce them without trade by giving up two washing machines. If Maxigania is going to receive a tomato from Elijastan, it must cost less than two washing machines or it will not make the trade.

Suppose that these nations negotiate a trade such that, for every tomato that Elijastan sends to Maxigania, Maxigania will send 1.5 washing machines to Elijastan. Will this be mutually beneficial? Well, suppose that Elijastan sends half of its tomatoes (50) to Maxigania. According to the terms of trade, Maxigania will send  washing machines to Elijastan. Without trade, Elijastan would have only 50 washing machines if it gave up 50 tomatoes. Now it has 75 washing machines and 50 tomatoes. That’s better because it can now consume beyond its PPC, at point C in the graph.

washing machines to Elijastan. Without trade, Elijastan would have only 50 washing machines if it gave up 50 tomatoes. Now it has 75 washing machines and 50 tomatoes. That’s better because it can now consume beyond its PPC, at point C in the graph.

What about Maxigania? It sent 75 washing machines to Elijastan, which seems like a lot, because it now has only 5 washing machines left. But it received 50 tomatoes in return. Given its resources and technology, 50 tomatoes weren’t even possible without trade. That’s better for Maxigania too, and we see that point C is beyond its PPC.

Still Struggling

Still Struggling

At first it can be difficult to see where mutually beneficial terms of trade must be negotiated. One quick way to find the terms of trade is to go back to the opportunity cost of the good on the x axis. It costs Maxigania two washing machines for each tomato produced. It costs Elijastan one washing machine for each tomato produced. Elijastan has a comparative advantage in tomatoes, and the terms of trade must be somewhere between one and two washing machines for each tomato traded.

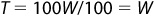

In other words, mutually beneficial terms of trade will exist when the exchange price is somewhere between the two countries’ opportunity costs. Recall from our mathematical example that for Maxigania,  and for Elijastan,

and for Elijastan,  . Therefore, a mutually beneficial trading price for washing machines would be between

. Therefore, a mutually beneficial trading price for washing machines would be between  T and 1T. Similarly, for Maxigania,

T and 1T. Similarly, for Maxigania,  , and for Elijastan,

, and for Elijastan,  . Therefore, a mutually beneficial trading price for tomatoes would be between 1 and 2 washing machines. In our example, the price of tomatoes was

. Therefore, a mutually beneficial trading price for tomatoes would be between 1 and 2 washing machines. In our example, the price of tomatoes was  (which is between the two countries’ opportunity costs), and the price of washing machines was

(which is between the two countries’ opportunity costs), and the price of washing machines was  (which is between the two countries’ opportunity costs).

(which is between the two countries’ opportunity costs).

When nations trade goods as in the example just given, they must also trade currencies. After all, the tomato growers in Elijastan want to be paid in their own currency so that they can spend the money in their own nation. When American companies sell products to European consumers, they don’t want to be paid in euros, they want to be paid in dollars. And when Mexican firms sell their products to Americans, they want to be paid in pesos, not in dollars. This implies that the flow of goods and services is associated with a flow of currencies. The flow of currencies is facilitated by currency markets.

Suppose we focus on the trade between Mexico and the United States. The market for the U.S. dollar is priced in how many pesos it takes to buy a dollar. The supply of dollars (S$) comes from Americans or anyone else who has dollars in his possession. The demand for dollars (D$) comes from those who wish to buy goods made in America because they are priced in dollars. Figure 17-5 shows the market for U.S. dollars. At the equilibrium in the market, the current price of a U.S. dollar is 10 Mexican pesos. This is often called the exchange rate.

FIGURE 17-5 • The Market for U.S. Dollars

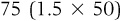

Of course, there is also a market for Mexican pesos. The market for pesos is the mirror image of the market for dollars. If it takes 10 pesos to get one dollar, it takes  of a dollar to get one peso. Figure 17-6 shows the market for pesos.

of a dollar to get one peso. Figure 17-6 shows the market for pesos.

FIGURE 17-6 • The Market for Mexican Pesos

Just as market forces cause the prices of gasoline and clothing to change, market forces cause the price of a currency to change. We look at how the price of dollars and pesos can be affected by market forces and how rising and falling exchange rates affect the flow of trade between nations. Continuing the previous example, the market for the U.S. dollar is currently in equilibrium, and the exchange rate is 10 pesos to the dollar.

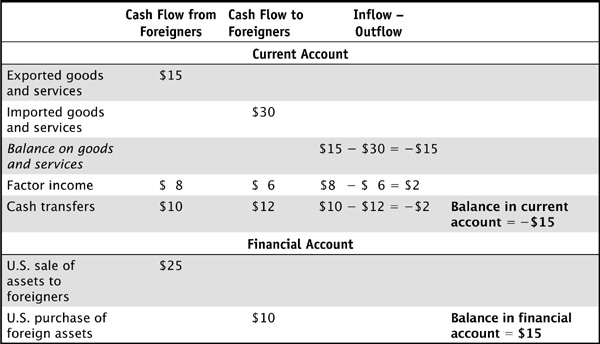

Suppose that the Mexican economy is experiencing a very strong recovery from a recession. Incomes are rising, and Mexican consumers are increasing their consumption of goods imported from the United States. If Mexican consumers want to buy American-made products, they are going to need dollars. And in order to get those dollars, they are going to need to supply their pesos in the market for pesos at the going exchange rate. Simultaneously, these transactions cause an increase in the supply of pesos and an increase in the demand for dollars. Suppose that when each market reaches a new equilibrium, the new price of a dollar is 12.5 pesos. This implies that the new price of a peso is $0.08. These shifts are seen in Figure 17-7.

FIGURE 17-7 • Changes in Exchange Rates

Because it now takes more pesos to buy a U.S. dollar, the dollar is said to have appreciated in value. And because it now takes fewer dollars to buy a peso, the peso is said to have depreciated in value. There are several general reasons why demand for a currency may increase or decrease:

1. Incomes in one nation are rising faster than incomes in other nations. When a nation’s economy is booming relative to those of its trading partners, that nation will import more goods from the other nations.

2. Inflation is more rapid in one nation than in others. If prices in Mexico are rising rapidly, but prices in the United States are stable, Mexican consumers will increase their demand for American-made goods and thus increase their demand for dollars. This is because American goods are now relatively cheaper to Mexican consumers.

3. Interest rates are higher in one nation than in others. If interest rates in the United States are higher than they are in Mexico, Mexicans will want to save their money in American financial assets like Treasury bonds. To do this, these savers increase their demand for dollars.

4. Stronger preferences for goods made in one nation over others. If Mexican consumers find American goods to be of higher quality, or more fashionable or trendy, then the demand for those goods, and the dollars needed to buy them, will increase.

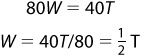

So how do exchange rates affect us on a daily basis? Suppose that you are an American who is planning a vacation in Mexico. When the exchange rate is 10 pesos to the dollar (or $0.10 dollar to the peso), your research discovers that you can reserve a hotel room that is priced at 1,000 pesos per night. If that exchange rate stays constant, this room will cost you $100 per night (1,000 pesos divided by 10 pesos per dollar). But suppose that the peso depreciates, and now each dollar can be exchanged at the rate of 12.5 pesos. The price of the hotel room for an American traveling to Mexico is now $80 (1,000 pesos divided by 12.5 pesos per dollar). So an appreciating dollar (each dollar buys more pesos) is good news for those who have dollars, like American consumers and firms that are looking to buy things in Mexico.

An appreciating dollar is also good for Mexico because more tourists will come from the United States to spend their new “stronger” dollars, and even those who stay home will purchase more goods produced in Mexico. Mexican vegetables will be less expensive in American grocery stores, for example. So when the dollar is appreciating against the peso, we expect to see more dollars flow to Mexico as Americans import more products from Mexico.

On the other hand, the Mexican peso is depreciating when the dollar is appreciating. Each peso now buys only $0.08, so Mexican consumers will find American-made products more expensive. They will reduce their imports from the United States, and they will find it more expensive to travel to the United States for business or pleasure. Therefore, a depreciating peso causes fewer pesos to flow from Mexico into the United States as Mexicans import fewer products from the United States.

From Chapter 14, we know that when net exports decline, aggregate demand in the United States will shift to the left, reducing GDP and the price level, and increasing unemployment. A stronger dollar (and a weaker peso) reduces exports from the United States to Mexico and increases imports from Mexico into the United States. All else equal, this falling component of aggregate demand can weaken the U.S. economy. On the other hand, net exports in Mexico are rising because of a weaker peso, which, all else equal, should boost this component of the Mexican economy. Panel a of Figure 17-8 shows the negative impact that the stronger dollar has on aggregate demand in the U.S. economy, and panel b shows the positive impact that the weaker peso has on aggregate demand in the Mexican economy.

FIGURE 17-8 • Effect of a Stronger Dollar and Weaker Peso on (a) the U.S. Economy and (b) the Mexican Economy

Nations track the international flow of currency, goods and services, and physical and financial assets in their balance of payments accounts. Money from other nations can flow into the United States in several different ways:

• An American firm sells a foreigner a good or service.

• An American receives a foreign payment for her labor.

• An American company is sold to a foreign buyer.

• An American firm sells a financial asset to a foreign buyer.

• The U.S. government sells either financial assets or physical assets to foreigners.

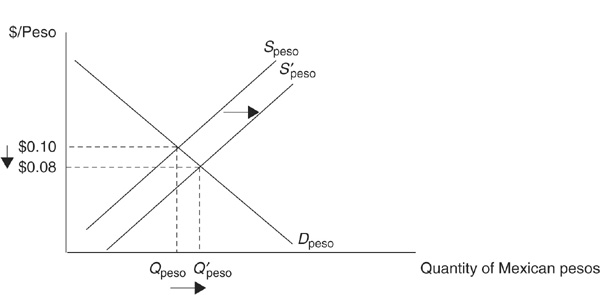

We can think of transactions between nations as either those that are of a short-term nature or those that are more long-term investments. Table 17-3 shows a simplified and very hypothetical balance of payments for the United States for 2010.

TABLE 17-3 Hypothetical Balance of Payments for the United States

Short-term transactions are included in the current account and include the import and export of goods and services and the flow of money as income for foreign and domestic labor. For example, in the table, the United States exports $15 worth of goods and services to other nations and imports $30 worth of goods and services from other nations. This reflects a trade deficit in goods and services and is a typical result in the U.S. balance of payments. If exports had exceeded imports, there would have been a trade surplus.

The current account also includes factor income that flows across borders. For example, if a British publisher pays an American author to write a book, this will show up as money that flows into the United States. Of course, companies in the United States also make factor payments to foreign workers.

The table indicates that $2 more money flowed into the United States than flowed out for factor payments.

The final entry in the current account is the transfer of cash across borders, called remittances. For example, a person from Guatemala may come to the United States and take a construction job. If he sends some of his wage dollars back to Guatemala, it would be recorded as dollars flowing out of the United States.

The balance of payments on the financial account tracks the flow of cash across borders for long-term assets, both physical and financial. For example, if an American company buys a building in Japan, this is a purchase of a physical asset and an outflow of dollars to Japan. If a Chinese bank buys a U.S. Treasury bond, this is a foreign purchase of a financial asset and an inflow of dollars into the United States. The Federal Reserve Bank and foreign central banks also engage in the buying and selling of U.S. financial assets, so this flow of dollars is not limited to private firms and individuals. Table 17-3 shows that the balance of payments on the financial account is positive.

It is no coincidence that the deficit in the current account is offset by the surplus in the financial account. For the most part, this is true of the actual balance of payments accounts. Why? The answer lies in the fact that U.S. dollars are really most useful when they are being used to either consume U.S. goods or invest in U.S. assets, including financial assets. Suppose that the United States has a trade deficit in goods and services. This means that foreign nations have sold Americans more goods and services than America has sold to them. Those foreign firms, citizens, and governments have a surplus of dollars on their hands. What will they do with the dollars? They will seek to invest them in physical assets, perhaps buying a company or a building, or financial assets, perhaps buying shares of stock in a U.S. company, saving their dollars in a U.S. bank, or purchasing U.S. Treasury bonds. If the United States had a current account surplus, the opposite would occur; Americans would have a surplus of foreign currencies, and they would find ways to invest those currencies back in those nations.

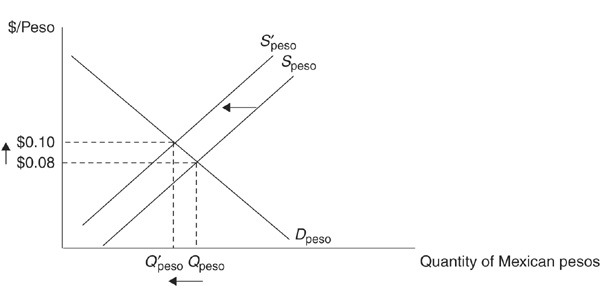

The flow of cash between nations can also be influenced by domestic policies, particularly monetary policy. For example, suppose the Federal Reserve has used expansionary monetary policy to fight fears of higher unemployment. The effect of the monetary policy is to decrease interest rates and increase aggregate demand, but it also affects the international flow of dollars.

As interest rates in the United States begin to fall, the return on financial investments in the United States is less attractive to foreign investors. If we return to the example of the dollar and the Mexican peso, this would imply that Mexican investors would decrease their demand for dollars and decrease their supply of pesos to these financial markets.

Figure 17-9 below shows the impact of this monetary policy in the market for the dollar. The decreased demand for dollars causes the value of the dollar to depreciate. The peso is simultaneously appreciating. Because the peso is appreciating against the dollar, Mexican consumers will find American goods to be less expensive, thus increasing imports from America. This should cause net exports in the United States to rise, and this will also help to increase aggregate demand in the United States.

FIGURE 17-9 • Effect of Expansionary Monetary Policy on the Dollar-Peso Exchange Rate

So far in this chapter, we have discussed the benefits of free trade and the impact that trade has on the flow of currency across international borders. The final topic of this chapter is trade barriers.

The United States and many other nations grow sugar cane to make sugar. Suppose that in the domestic U.S. market for sugar, when trade does not exist, the price is $800 per ton, and 100,000 tons are consumed in equilibrium. Figure 17-10 shows the U.S. sugar market. If the price on the world market is $700 per ton, U.S. consumers would increase the quantity demanded to 120,000, but U.S. sugar producers would reduce their production to 80,000 tons. The difference between the domestic quantity supplied and the domestic quantity demanded (40,000 tons) is the amount of sugar that would be imported into the U.S. market.

FIGURE 17-10 • The U.S. Sugar Market

Consumers definitely benefit from imported sugar at the lower price because their area of consumer surplus increases by the trapezoidal area shaded in Figure 17-10. Foreign suppliers of sugar benefit because they are able to expand their exports to the U.S. market. American sugar producers are not pleased because they have lost producer surplus and market share to the foreign competition.

Suppose sugar producers in the United States ask the government to protect them from foreign sugar imports by levying a tariff on imported sugar. A tariff is like an excise tax that is applied only to imported sugar and increases the U.S. price in Figure 17-11 to $750. At this higher price, quantity demanded falls to 110,000 tons, and domestic quantity supplied rises to 90,000 tons. After the tariff, only 20,000 tons of sugar are imported.

FIGURE 17-11 • Effect of a Tariff on the U.S. Sugar Market

There are clear winners and losers from this tariff policy. Consumers lose some consumer surplus, while domestic producers gain back some producer surplus because the price has risen. Foreign sugar producers lose some customers and market share in the United States, and the U.S. government collects tariff revenue equal to $1,000,000 ( tons). Deadweight loss also exists because part of the gray trapezoid from Figure 17-10 doesn’t go to anybody. This is seen as two small triangles in Figure 17-11.

tons). Deadweight loss also exists because part of the gray trapezoid from Figure 17-10 doesn’t go to anybody. This is seen as two small triangles in Figure 17-11.

Governments also use import quotas to reduce the quantity of a good that is allowed into the domestic market from foreign producers. Suppose in Figure 17-10 that the U.S. government had chosen to reduce the quantity of imported sugar from 40,000 tons to 20,000 tons. The impact of the quota would have been identical to the impact of the tariff, with one exception: there would have been no government tariff revenue.

In addition to the negative consequence of deadweight loss, economists generally disapprove of tariffs and quotas because they protect inefficient domestic producers at the expense of consumers and more efficient foreign producers. Foreign competition gives domestic producers a big incentive to produce their goods as efficiently as possible and to engage in research and development to improve their production technology. These improvements provide opportunities for long-run economic growth in the domestic economy.

This chapter began by introducing the production possibilities model and using it to show how nations can mutually gain from trade based upon comparative advantage. We then introduced the market for foreign currency and used that market to explain how and why currencies appreciate and depreciate and how changes in the value of a currency affect net exports. Next, we discussed the balance of payments statement, which tracks the flow of dollars to and from foreigners. A connection was made between monetary policy, the interest rate, and foreign exchange markets. Finally, the impact of tariffs and quotas was presented to show that these forms of trade barriers create inefficiencies.

Is each of the following statements true or false? Explain.

1. Nations that trade on the basis of comparative advantage can consume beyond their production possibilities curve.

2. If a large nation can outproduce a small nation in all goods and services, there is no way that the large nation can benefit by trading with the small nation.

3. Tariffs and quotas both create deadweight loss, but quotas lower the price of an imported product, while tariffs increase the price of that product.

4. If the dollar has appreciated against the euro, we know that the demand for the dollar has increased.

5. A trade deficit occurs when a nation imports more goods and services than it exports.

For each of the following, choose the answer that best fits.

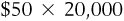

Use Table 17-4 to answer questions 6 and 7.

6. Suppose that Spain and Portugal can both produce wine and cheese. The production possibilities are given in Table 17-4. If Spain uses all its resources to produce wine, it can produce 30 units of wine. If it uses all its resources to produce cheese, it can produce 30 units of cheese. Likewise, if Portugal uses all its resources to produce wine, it can produce 10 units of wine. If it uses all its resources to produce cheese, it can produce 20 units of cheese. We know that:

A. Spain has an absolute advantage in both wine and cheese.

B. Spain has an absolute advantage in wine, and Portugal has an absolute advantage in cheese.

C. Portugal has a comparative advantage in both wine and cheese.

D. Spain has a comparative advantage in wine, and Portugal has an absolute advantage in cheese.

7. Suppose that Spain and Portugal can both produce wine and cheese. The production possibilities are given in Table 17-4. If these nations trade based on comparative advantage,

A. Both nations will consume inside their production possibilities curve.

B. Spain should trade cheese to Portugal in exchange for wine.

C. Portugal should trade cheese to Spain in exchange for wine.

D. There is no trade that can allow these nations to consume beyond their PPCs.

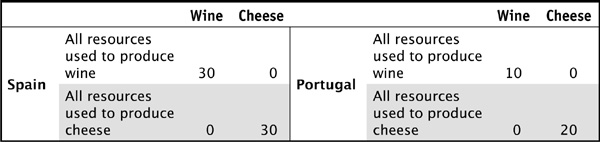

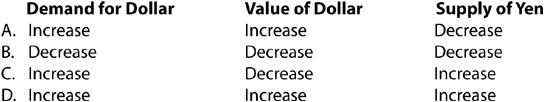

8. The United States and Japan engage in trade with each other. Suppose that the Federal Reserve increases interest rates through monetary policy. Given this, how would the demand for the dollar, the value of the dollar against the Japanese yen, and the supply of the yen change?

9. Suppose the United States trades with the nation of Ame. The currency of Ame is the quid. If American consumers become infatuated with all products made by Ame, we would expect the _____ dollars to _____ and the quid to _____against the dollar.

A. demand for; increase; appreciate

B. supply of; increase; appreciate

C. demand for; decrease; depreciate

D. supply of; decrease; depreciate

10. Which of the following would not be a typical consequence of an import tariff?

A. Producer surplus increases in the domestic market.

B. Consumer surplus increases in the domestic market.

C. Deadweight loss is created.