In Chapters 11, 12, and 13, we discussed the three most widely used measures of macroeconomic performance: GDP, unemployment, and the price level. However, these are just measures of the macroeconomy, the outcomes of how an economy works, rather than a model to tell us how it works. In this chapter, we turn our attention to the model of aggregate supply and aggregate demand, which helps us understand how the price level is determined and the fluctuations that we tend to see in unemployment and GDP.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. Describe the business cycle.

2. Describe aggregate demand and aggregate supply.

3. Use the aggregate demand and aggregate supply model to show how economic fluctuations occur.

4. Relate full-employment production to the natural rate of unemployment.

5. Describe and graph what is meant by economic growth.

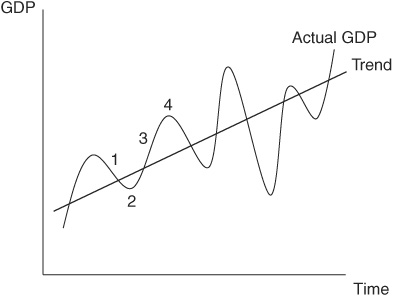

Macroeconomic policy has three major goals: price stability, an appropriate amount of unemployment, and economic growth, which is the ability of an economy to produce more goods and services. As we have discussed in the previous three chapters, however, there is fluctuation in prices and employment as GDP fluctuates. In fact, even though output has increased over time, this increase doesn’t happen consistently or continuously. There are periods of time when output is expanding and periods of time when output is falling, but the amount of output in an economy tends to increase gradually over time. We can visualize these fluctuations in Figure 14-1.

FIGURE 14-1 • The Business Cycle

Figure 14-1 illustrates the business cycle, which is the alternation between expansions (when GDP and employment are rising) and contractions (when GDP and employment are falling). The four stages of the business cycle are (1) contraction, (2) trough (or bottom), (3) expansion or recovery, and (4) peak. There is no strict rule, but for the most part, when output and employment have fallen for six months or more, this is called a recession. If a recession is severe and prolonged, it is called a depression. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, which is the group that officially declares a recession, there have been 11 recessions in the United States since World War II, and the average length of the business cycle (from one peak to the next) is about five years and seven months. Despite these recessions, however, the economy is growing on average. The trend line in Figure 14-1 shows the average rate of growth over the same time period. In the United States, the economy has grown, on average, about 2.8 percent every year. This means that over the long run, the economy is able to produce 2.8 percent more goods and services every year, even if the growth is more than 2.8 percent in some years and less than 2.8 percent (or even negative) in other years.

Economic growth accumulates, so if GDP is $100 in year 1 and the growth rate is 5 percent, GDP is $105 in year 2 and will be 5 percent higher than $105 in year 3. This is a mathematical chain called an exponential expansion. Whenever you have an exponential expansion, there is a handy rule, called the rule of 70, that gives you the amount of time it takes for a number in that series to double:

So if the growth rate of GDP is 5 percent,  years. Given that the United States grows at an average rate of 2.8 percent, the U.S. economy can expect to double in about 25 years.

years. Given that the United States grows at an average rate of 2.8 percent, the U.S. economy can expect to double in about 25 years.

In Chapter 11, we calculated GDP using the expenditures approach, where

To do this, we added up the dollar value of all of the goods and services for each category. However, we noted in Chapter 13 that dollar values and prices change frequently. This means that if we fail to account for changes in prices, we may believe that we are producing more goods and services than we are, since prices going up would make our value of GDP go up as well.

We need to make an important distinction between nominal GDP and real GDP. Nominal GDP is the calculation of GDP using current prices. For example, if you are calculating GDP in 2010, you would use the prices that goods sold for in 2010. Real GDP, on the other hand, adjusts nominal GDP to account for price changes. This can be done in a few different ways. One common way is to calculate GDP using the same prices every year. Using this method, you would use the prices that exist in 2010 to calculate GDP in 2009, 2008, and any other year. If you would like to review this technique of deflating nominal values to real values, there are a few examples given in Chapter 13.

We might also make a final adjustment to GDP by finding real GDP per capita. According to the World Bank, the GDP of India in 2010 was about $1.7 trillion and the GDP of Canada was about $1.5 trillion. It would be incorrect to conclude based on this that India had a higher standard of living than Canada. India, with a population of more than 1.2 billion people, has to spread that output out over a lot more people than Canada, with a population of 34 million. To compute GDP per capita, we divide GDP by the population (capita means “head” in Latin). In fact, the GDP per capita in Canada in 2010 was $46,060, while Indian GDP per capita was only $1,477.

If our goal is to achieve economic growth while maintaining a healthy level of unemployment and price stability, it would be useful to have a model to help us understand how output and price level change. After all, we used the model of supply and demand in microeconomics to help us understand how a single market achieved an equilibrium price and quantity. The model that macro-economists use to explain the short run fluctuations in output around the long-run trend is the model of aggregate supply and demand (AD-AS model), and it is shown in Figure 14-2.

FIGURE 14-2 • The AD-AS Model

The AD-AS model should look familiar, as it closely resembles the supply and demand model. In the AD-AS model, however, we use aggregate demand (AD), short-run aggregate supply (SRAS), and an additional curve, long-run aggregate supply (LRAS). There are some other important distinctions to make as well:

1. A price level, rather than a single price, is on the vertical axis. In this model, we are talking about the price of all goods and services, so we need some measure that represents the price level (such as the CPI) to capture what the overall level of prices is.

2. The dollar value of output is on the horizontal axis. Recall that we cannot simply add together all of the output in an economy; we need to denominate it using dollars. However, we want to capture the real value of the goods and services being produced, so we use real GDP to capture this.

3. The equilibrium in this economy is the price level (PLyear) that a country experiences in a given year and the actual level of output that a country produces each year (Yyear). For instance, if we were to use the CPI as our measure of the price level, for the United States in 2010,  and

and  trillion.

trillion.

4. Notice that the equilibrium in this economy is less than Yf, which is the full-employment level of output. You can think of Yf as an ideal amount of production of goods and services.

Another key difference between the AD-AS model and the supply and demand model is the curves used. As you can see, there are three curves in this model rather than two. We will discuss each of them more in depth.

Our AD-AS model is an aggregation of all of the markets in an economy. This means that aggregate demand is the curve that represents all spending on goods and services and the relationship of that spending to the aggregate price level. Aggregate demand is thus the quantity of output that would be demanded at any possible price level by households, businesses, the government, and the rest of the world. The equation representing AD is

An astute observer will note that this is the same as the equation we gave for GDP using the expenditures method. This is not surprising, as they both represent spending on all goods and services in an economy. The difference is that GDP represents a particular point on the AD curve (a particular level of GDP given the price level), and the AD curve itself represents the hypothetical GDP that would be purchased at varying price levels.

Like demand in microeconomics, AD is downward-sloping, as illustrated in Figure 14-3. However, demand in microeconomics is downward-sloping because of the law of demand. Recall that a movement along a demand curve is a change in the quantity demanded for a good holding all other determinants of demand constant; in the AD-AS model, we are instead considering an aggregate change in the prices of all goods and services. Our AD curve states that people will consume different amounts at different price levels. Why is this the case?

FIGURE 14-3 • The AD Curve

The AD curve is downward-sloping for three reasons:

• The wealth effect (aka the Pigou wealth effect). When there is an increase in the price level, the purchasing power of money goes down. For instance, if you had $1,000 in a non-interest-bearing account, your effective wealth would decrease when there was an increase in the price level. People are less able to purchase goods and services when the price level increases, and more able to purchase goods and services when the price level decreases, because their wealth changes.

• The interest-rate effect. When the price level goes up, people need to hold on to more money, as opposed to keeping it in the form of assets like a bank account, in order to purchase goods and services. Suppose you normally buy $100 in goods and services in a week, but the price level goes up 20 percent. You now need to keep 20 extra dollars on hand to purchase the same goods. However, when you keep that in your wallet instead of in the bank, the bank can no longer lend that money out; this reduces the funds available to borrowers and drives up the interest rate. When the interest rate increases, this lowers the amount of investment, the I part of AD. Therefore, as the price level increases, the amount of AD decreases.

• Exchange-rate effect. When the price level in one country increases, people naturally look to other countries to purchase goods and services elsewhere. This increases imports, which lowers aggregate demand. Remember that goods imported from other nations are subtracted from the home nation’s GDP.

These three effects explain why the AD curve is downward-sloping, or what causes movements along the AD curve. What if more aggregate output is demanded when the price level hasn’t increased? This implies that the AD curve must have shifted. When AD increases, the AD curve shifts outward (or to the right). When AD decreases, the AD curve shifts inward (or to the left). Shifts in aggregate demand are shown in Figure 14-4.

FIGURE 14-4 • Shifts in the AD Curve

Several factors can cause a shift in AD, but the following are the most common:

• Changes in expectations. When firms decide to invest, either by expanding their inventory or increasing their productive capacity, they do so because they expect to sell more goods and services in the future. Likewise, consumers plan purchases based on their expectations of income, expectations about needing to save, and a variety of other considerations. If consumers and firms are more optimistic, AD will increase. If consumers and firms are more pessimistic, AD will decrease.

• Changes in wealth. In 2008, a housing “bubble” burst. That is, the prices and values of houses suddenly and dramatically decreased. For many families, their homes are their largest asset, so a dramatic decrease in the value of a family home is a decrease in that family’s wealth. Moreover, a fall in the value of a home curtails the ability to borrow against that asset for consumer spending, such as through a home equity loan. This collapse in housing prices was partly responsible for the decrease in consumer spending in 2008, and thus decreased AD.

• Government policies. The government can influence AD through two types of policy: fiscal policy and monetary policy. Fiscal policy is the use of government spending, which directly changes the G component of AD, or the use of taxes to influence the C or I component. If the government increases spending or reduces taxes, then AD increases. Monetary policy is the use of the money supply to influence interest rates, which in turn influences the C and I components of AD. When the government, through its central bank, increases the money supply, interest rates fall, and this increases aggregate demand. (We discuss these in more depth in Chapter 16.)

The counterpart to AD in the AD-AS model is aggregate supply (AS). This is a little misleading, however. We actually distinguish between two different AS curves, short-run aggregate supply (SRAS) and long-run aggregate supply (LRAS). In this model, the short run applies to the period of time in which production costs can be taken as fixed. The SRAS curve is therefore a graphical representation of the relationship between the aggregate amount of output that is supplied and the price level. The LRAS curve has a different intuition entirely from a microeconomic supply curve—it represents the potential output of an economy if all prices have adjusted. It is vertical because along the LRAS, all prices have adjusted, and therefore there is no longer a relationship between the price level and output. Moreover, it is vertical at a specific level of output—the output at which all inputs to production are used the most effectively and appropriately.

The SRAS curve is upward-sloping, which means that higher levels of GDP supplied are associated with higher price levels, at least in the short run. It isn’t necessarily true, and doesn’t necessarily make sense intuitively, that firms would produce more in response to higher price levels, but we do see more production at higher price levels. There are three main theories that may explain why this occurs:

• Misperceptions theory. According to misperceptions theory, price changes temporarily confuse or mislead firms about relative prices. For instance, a firm might mistakenly believe that the demand for its good has increased when it can sell the same quantity of goods at higher prices.

• Sticky price theory. The prices of some goods do not respond very quickly. Thus, if the price level decreases, firms may not adjust their prices and end up selling more goods.

• Sticky wage theory. Labor contracts tend to be fixed for periods of time (for instance, annual salary revisions). If there is inflation, labor is relatively cheaper in real terms and firms can produce more at lower real cost.

In the short run, output may be different at different price levels. In the long run, on the other hand, prices have had a chance to fully adjust and the level of production is independent of the price level. It will depend instead on what the economy actually uses to produce goods and services (that is, a country’s stock of the inputs of production) and the technology that an economy uses to combine these inputs to create goods and services. The LRAS curve is a straight line that is vertical at the full-employment level of output. Recall that the full-employment level of output is an ideal level of output—the level of output that is produced when employment is at the natural rate of unemployment (the NAIRU).

Like AD, our SRAS and LRAS curves may shift when conditions change. LRAS depends on the stock of the inputs to production (land, labor, capital, and technology), and when the stock of one or more of these inputs increases, LRAS increases (or shifts to the right). For instance, if a country finds a new source of energy (counted in “land”), the LRAS curve would shift to the right, as shown in Figure 14-5. LRAS can also decrease if the stock of one of the factors of production goes down. This is particularly relevant to capital. Capital depreciates, which means that an economy must engage in at least some investment in order to maintain its stock of capital. If investment falls too low, the stock of capital decreases, and the economy’s potential for production also decreases.

FIGURE 14-5 • A Positive Shift in the LRAS Curve

On the other hand, shifts in SRAS occur when the prices of one or more of these inputs to production change. For instance, Figure 14-6 shows the effect on SRAS if the price of labor increases. Here, the cost of production will increase for the entire economy, and the SRAS supply curve decreases (shifts to the left). Since the amount or stock of labor that exists in the economy hasn’t changed, the LRAS remains unchanged.

FIGURE 14-6 • A Negative Shift in the SRAS Curve

The AD-AS model uses aggregate supply and aggregate demand to analyze economic fluctuations. As in the supply and demand model we have seen, equilibrium in the macroeconomy occurs when the quantity of aggregate output supplied is equal to the quantity of aggregate output demanded. However, in the macroeconomy, we have two outcomes that we are concerned about: short-run macroeconomic equilibrium and long-run macroeconomic equilibrium.

In the short run, there is a short-run aggregate price level and a short-run aggregate output associated with the short-run macroeconomic equilibrium. As shown in Figure 14-2, this occurs at the intersection of AD and SRAS. The intuition here is similar to the supply and demand model in that if the amount of aggregate output demanded differs from the amount of aggregate output supplied, the price level will adjust to restore macroeconomic equilibrium.

If there is a shock to the macroeconomy, the short-run equilibrium will change, leading to fluctuations in the price level and output. Consider a negative aggregate demand shock that occurs because consumers become pessimistic about the future. Such a shock would shift the AD curve to the left, as shown in Figure 14-7. As a result, aggregate output in the economy would decline as well as the price level. Note that this also has implications for employment: if there is less GDP being produced, there is less need for workers, and the unemployment rate will increase.

FIGURE 14-7 • A Negative Demand Shock

Similarly, there can be positive economic shocks. For instance, if people become relatively wealthier, aggregate demand will increase, as shown in Figure 14-8. As a result, output and price levels increase. This also has an effect on unemployment, as more production requires more workers. This is an important fact about our measures of macroeconomic performance: output and employment tend to move in the same direction (conversely, output and unemployment move in opposite directions).

FIGURE 14-8 • A Positive Demand Shock

Macroeconomic fluctuations can also be the result of fluctuations in SRAS. Consider what happens to our model if the price of energy increases—SRAS decreases (shifts to the left), which results in a higher price level and a lower output, as shown in Figure 14-9. This combination of stagnation of output and inflation even has a special term, stagflation. This is a particularly bad situation—falling output means rising unemployment and falling incomes even while people have to pay higher prices (we will see in Chapter 16 that this is particularly problematic for policy makers who are attempting to solve these dual problems).

FIGURE 14-9 • A Negative Supply Shock

Long-run macroeconomic equilibrium is shown in Figure 14-10. This occurs when the actual amount of production is at the ideal level. Here, prices have fully adjusted, the economy is operating at its full potential, and unemployment is at the natural rate.

FIGURE 14-10 • Long-Run Macroeconomic Equilibrium

To understand why events like recessions or expansions occur, let’s consider what happens when an economy that is in long-run equilibrium experiences a shock, as in Figure 14-11. The economy is initially in long-run equilibrium with a price level of PL1 and an output of Y1. Suppose consumer confidence in the economy falls, as in our previous example. As a result, AD shifts to the left, and the economy is now in short-run equilibrium at Y2 and PL2. Output has decreased, which leads to higher unemployment. The difference between the current output (Y2) and the full-employment output (Yf) is called a recessionary gap; it can be caused by either a negative supply shock or a negative demand shock.

FIGURE 14-11 • Effects of a Negative Demand Shock

Over time, one of two things will happen. One possibility is that something restores AD to its initial position, either a change in consumer confidence or some sort of policy (as we will discuss in Chapter 16). Another possibility is that, since the unemployment rate has increased, people become willing to work for lower wages in order to get jobs. This would shift the SRAS curve to the right, returning output to the full-employment level, but at a lower price level. It should be noted that this self-correction back to full employment might take quite some time. Because lengthy recessions are quite painful for households and businesses, the government will rarely sit idly by and wait for the SRAS curve to return the economy to full employment.

Conversely, an inflationary gap occurs when the current output exceeds the full-employment output. An inflationary gap is caused by either a positive supply shock or a positive demand shock. Consider an economy that is currently in long-run macroeconomic equilibrium, but an increase in consumer confidence increases AD. This would cause a rightward shift in the AD curve, as shown in Figure 14-12. As a result, unemployment drops below the NAIRU, placing upward pressure on wages, which increases production costs and shifts SRAS to the left, returning the economy to long-run equilibrium.

FIGURE 14-12 • Effects of a Positive Demand Shock at Long-Run Equilibrium

Still Struggling

Still Struggling

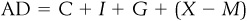

Table 14-1 will help you keep track of how changes in the factors affecting SRAS and AD will lead to macroeconomic fluctuations. Note that all of these are short-run changes—in the long run, output will return to the full-employment level of output and the natural rate of unemployment, although there may be a different price level.

TABLE 14-1 Effects of Changes in Factors Affecting SRAS and AD

The fluctuations that cause recessions and expansions are explained by shifts in AD and/or SRAS. But in Figure 14-1 we show that even with fluctuations, there is an increase in GDP over time. This economic growth reflects an increase in the ability of an economy to produce goods and services, not merely a temporary spike in production. The only way an economy can grow, therefore, is to increase its capacity. This is reflected in our AD-AS model as a shift to the right of the LRAS curve as a result of an increase in the stock of inputs or an improvement in technology. This can occur in the following ways:

• An increase in labor. An increase in either the quantity of labor or the quality of labor (sometimes called human capital) expands the potential labor force of an economy.

• An increase in natural resources. This would result from things such as the discovery of new energy sources or more efficiency in using energy resources.

• An increase in the capital stock. This occurs through investment.

• An improvement in technology. This occurs if better ways of combining resources are developed to produce more goods and services using the same technology.

One special branch of macroeconomics called growth theory is interested in determining which of these changes have led to economic growth and how to create more economic growth. Recall that real GDP per capita is a better indicator of the well-being of a country than merely real GDP. This means that if a population is growing, an economy must continue to expand if it is to maintain or improve its well-being. The relative importance of each of these factors in economic growth has changed over time. During the Industrial Revolution, much of the economic growth that occurred was due to increases in the stock of capital. More recently, improvements in human capital and technology seem to be better explanations for economic growth.

In this chapter, we introduced the AD-AS model to explain the fact that economies experience contractions and expansions of output. Shifts in SRAS and AD explain the temporary fluctuations around a long-run trend of economic growth, which is explained by shifts in LRAS. One of the factors that shift aggregate demand is government policies in the form of monetary policy and fiscal policy. In order to understand monetary policy, however, we need to explore money in a little more depth. This is the focus of the next chapter.

Is each of the following statements true or false? Explain.

1. A decrease in LRAS is not possible.

2. All else equal, if consumer confidence increases, inflation will occur.

3. Long-run equilibrium is associated with an unemployment rate of zero.

4. It is not possible to produce beyond the full potential employment.

5. A recession is any decrease in a nation’s output.

For each of the following, choose the answer that best fits.

6. The point in the business cycle when an economy is at “rock bottom” is called the:

A. Peak

B. Expansion

C. Contraction

D. Trough

7. Which of the following leads to an initial increase in the aggregate demand of an economy?

A. An increase in the price of energy

B. A decrease in consumer wealth

C. An increase in investment

D. An increase in the wage rate

8. Which of the following is a possible explanation for why SRAS is upward-sloping?

A. Sticky wages

B. The wealth effect

C. The exchange-rate effect

D. The interest-rate effect

9. Which of the following would lead to economic growth?

A. A decrease in the wage rate

B. An improvement in education

C. An increase in consumer confidence

D. An decrease in investment

10. An inflationary gap would be caused by which of the following changes?

A. An increase in the price of energy

B. An increase in the wage rate

C. An increase in the price of capital

D. An increase in consumer wealth