Fluctuations in the macroeconomy are common, but large or prolonged swings in unemployment, output, and inflation can have serious effects on an economy. Traditionally, economic theory held that the best course of action when these things happened was to take no action at all. The Great Depression was a dramatic illustration of why this is not always the best idea. The alternative, to “do something,” generally takes the form of using either fiscal policy or monetary policy (or a combination of the two) to affect macroeconomic variables. In this chapter, we examine the classical approach, the methodology involved in using fiscal and monetary policy, and some criticisms that remain of using either to affect the macroeconomy.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. Describe the role of the interest rate and investment in the business cycle.

2. Describe and contrast the classical and Keynesian approaches to macroeconomic intervention.

3. Describe and graph the loanable funds market, and describe what effect government spending may have on the interest rate in this market.

4. Understand how fiscal policy is carried out and how this is reflected in the AD-AS model.

5. Define the terms crowding-out effect and multiplier effect, show how they affect aggregate demand in the AD-AS model, and be able to calculate the multiplier effect.

6. Understand how central banks undertake monetary policy and how this is reflected in the AD-AS model.

7. Describe and graph how monetary and fiscal policies affect macroeconomic variables such as GDP, unemployment, and inflation.

8. Describe the neoclassical synthesis and continuing debates in macroeconomics.

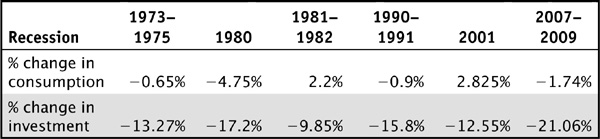

Before we move on to the different things that might be done to manage macroeconomic fluctuations, we need to revisit the role of the interest rate and investment. Investment is a critical part of GDP. Even though consumption typically makes up the largest share of GDP, investment plays a greater role in macroeconomic stability, and investment is much more volatile than consumption. Table 16-1 compares the average quarterly changes in the consumption and investment components of GDP during each of the previous six recessions. As you can see, not only did investment decline by significantly more than consumption, but consumption even increased during a few recessions!

TABLE 16-1 Changes in Consumption and Investment During Recessions

The amount of investment in the economy will depend on a number of factors, but foremost among them is the interest rate. There are two models of how the interest rate is determined in the short run. One of them, liquidity preference, we introduced in Chapter 15. There is another model for how interest rates are determined that is slightly different from the liquidity preference theory, the market for loanable funds model.

As the name market suggests, this model is based on the supply and demand structure that we are by now very familiar with. The supply of loanable funds is upward-sloping, and it originates from the savings that exist in an economy. Individual households and businesses supply their savings through financial intermediaries. The price that savers receive for their savings is the interest rate, and as the interest rate increases, the amount of savings that households are willing to supply increases (as the opportunity cost of consuming increases, households will decrease their consumption and save more). Demand is downward-sloping because loanable funds are used for investment, and the interest rate is the price of investing. The more expensive it is to borrow money, the lower the rate of return on an investment is going to be, and therefore the less investment you will do. For instance, suppose you have four projects with rates of return of 4 percent, 3 percent, 2 percent, and 1 percent. If the interest rate is 2.5 percent, you will invest in only two of those projects, but if the interest rate is 1.5 percent, you will invest in three of them.

Shifts in the supply curve for loanable funds occur when there are changes in savings behavior or changes in savings from other countries (we abstract from this in this chapter and revisit it in Chapter 17). Demand for loanable funds is basically a derived demand. Firms demand funds to invest, but they do so because they believe that the investment will be productive in the future. In addition, if a government runs a budget deficit, it must borrow money in order to pay for the amount of government spending above the amount of tax revenues that it collects. Therefore, changes in the demand for loanable funds occur when there are changes in the investment climate or changes in the government’s budget balance.

Let’s examine what the effect on the interest rate would be if there were an increase in the savings rate, using both the loanable funds model and the liquidity preference model from Chapter 15. Savings is an important aspect of investment. In fact, unless we have an influx of savings from another country, any investment that is done has to come from savings. This is reflected in the savings-investment identity,  . What would be the effect of an increase in savings on the interest rate in the short run, then? According to the liquidity preference model, an increase in savings would decrease the demand for money; since people would need less money on hand to carry out transactions (they are consuming less and saving more). As shown in panel a of Figure 16-1, this would lead to a decrease in the interest rate. Since we know that a lower interest rate will spur investment, this would lead to an increase in investment in the short run. On the other hand, in the market for loanable funds model, an increase in the savings rate would lead to an increase in the supply of loanable funds, as shown in panel b of Figure 16-1. Here, we see that an increase in the savings rate will lower the interest rate and increase the quantity of funds borrowed in the economy.

. What would be the effect of an increase in savings on the interest rate in the short run, then? According to the liquidity preference model, an increase in savings would decrease the demand for money; since people would need less money on hand to carry out transactions (they are consuming less and saving more). As shown in panel a of Figure 16-1, this would lead to a decrease in the interest rate. Since we know that a lower interest rate will spur investment, this would lead to an increase in investment in the short run. On the other hand, in the market for loanable funds model, an increase in the savings rate would lead to an increase in the supply of loanable funds, as shown in panel b of Figure 16-1. Here, we see that an increase in the savings rate will lower the interest rate and increase the quantity of funds borrowed in the economy.

FIGURE 16-1 • (a) Liquidity Preference Model of the Interest Rate; (b) Loanable Funds Model of the Interest Rate

You might notice that in both panels of Figure 16-1 the interest rate on the vertical axis is simply labeled as i, which would imply that the same equilibrium interest rate is observed in both markets. However, economists believe that the most appropriate interest rate to use in the money market model is the nominal interest rate, and the best interest rate to use in the loanable funds market is the real rate (which is frequently abbreviated as r). The nominal rate is equal to the real rate of interest plus expected inflation (or,  + inflation). In Chapter 13 we discussed how nominal and real values differ. Real values, whether they are interest rates or dollars, are adjusted for the effects of inflation. In a short-term period of time, we assume that there is no inflation; thus there is no difference between the real and the nominal interest rates, so in all of our graphs we use i to denote interest.

+ inflation). In Chapter 13 we discussed how nominal and real values differ. Real values, whether they are interest rates or dollars, are adjusted for the effects of inflation. In a short-term period of time, we assume that there is no inflation; thus there is no difference between the real and the nominal interest rates, so in all of our graphs we use i to denote interest.

Up until the 1930s, there was relatively little dissent among economists about models of the macroeconomy. The classical theory of economics referred to an understanding that the following were eternal truths:

• Prices fully adjust.

• Production will generate enough income to support the same level of demand.

• Savings and investment will equal each other.

In other words, short-run aggregate supply was almost an afterthought. Since prices always fully adjust, any change that affected short-run aggregate supply or aggregate demand would ultimately be neutral, and the macroeconomy would return to the full-employment level of output on its own. Additionally, the theory asserts that the full-employment level of output would always produce enough income for that output to be purchased, an idea known as Say’s law. In fact, this price adjustment is exactly what we showed in Chapter 14 as the short-run aggregate supply curve and the aggregate demand curve adjusted in response to changes in factors affecting the macroeconomy.

The implication of this is clear: any attempt to affect macroeconomic variables is at best unnecessary and at worst damaging. For instance, any attempt to change aggregate demand by using the money supply to lower the interest rate would not actually result in more output. This idea is embodied in another model used by classical economists, the quantity theory of money. According to the quantity theory of money, the amount of money that is used to purchase goods and services in an economy, which you can find by multiplying the price level, P, by the real GDP, Y, is equal to the dollar amount of the money supply multiplied by its velocity. The velocity of money is how often a unit of the money supply changes hands. Mathematically, the quantity theory of money is simply:

The classical theory of money states that prices fully adjust, so P is able to change, but Y is fixed in the short term. It also assumes that the velocity of money is relatively stable and reflects the spending habits and existing technology in the money supply. The implication here is also clear: if the money supply is changed, the only effect will be an increase in the price level (that is, inflation) with no effect on the variable we really care about, Y. In other words, according to the classical theory, money is neutral and has no effect on real variables (real GDP or unemployment). We could further argue that according to classical economics, there really is no such thing as a SRAS curve; the only supply curve in the macroeconomy is the LRAS.

Still Struggling

Still Struggling

The velocity of money is a tricky concept. Let’s explain this using a simple economy. Suppose an economy has only two goods, jelly and toast. There are four units of jelly and five units of toast in the economy.

First, suppose that the price of jelly is $1 and the price of toast is $2. In this case, total spending in the economy  . If the money supply in the economy is only $7, each of those dollar bills will have to change hands twice in order for $14 worth of goods to be sold. Thus we say that the velocity of money (V) is equal to 2.

. If the money supply in the economy is only $7, each of those dollar bills will have to change hands twice in order for $14 worth of goods to be sold. Thus we say that the velocity of money (V) is equal to 2.

If a dollar bill always changes hands twice in our economy, and the amount of jelly and toast are fixed (that is, V and Y are known), what happens if the money supply doubles to $14? We can use the quantity theory of money equation to predict that if the left side doubles, the right side must also double. And since it is assumed that output Y is constant, prices must also double. Thus classical economists believe that when more money is in circulation and chasing after the same goods, prices will be bid up.

As we alluded to in the first chapter, history proved that the classical theory had some problems. According to the classical theory, the Great Depression should never have been possible. The individual actions of private producers did not aggregate into an efficient macroeconomic outcome. Say’s law had fallen apart: supply did not create its own demand. Instead, allowing the macroeconomy time to self-adjust had led to a downward spiral. Such a spiral starts with something spooking aggregate demand and output going down, but since wages and other prices are not flexible downward, SRAS doesn’t adjust. In fact, the AS curve is completely horizontal up to the full-employment output.

The implication of this is also clear: any decrease in aggregate demand can potentially lead to a permanent reduction in output. Once an economy has started on a downward spiral, it cannot correct itself, and some sort of intervention is not just desirable, but necessary. Equally important is the implication about the impact of any action to correct aggregate demand—it will have no effect on the price level unless aggregate demand expands beyond full employment. In other words, according to Keynesian theory, any shift in aggregate demand will not cause inflation as long as output is below the full-employment level.

Figure 16-2 illustrates how the different assumptions of the classical and Keynesian models translate into an AD-AS model, and the consequences in terms of the price level of a shift in aggregate demand. In the classical model, there is only one aggregate supply curve, since prices always fully adjust. Any shift in aggregate demand will not actually increase output; it will only cause an increase in price level. On the other hand, aggregate supply in the Keynesian model has “sticky” prices that do not adjust. In this case, when aggregate demand increases, output will increase and the price level will not.

FIGURE 16-2 • (a) Classical Theory; (b) Keynesian Theory

Consider, then, an output gap as shown in panel b of Figure 16-2. The aggregate demand curve AD1 is currently below full-employment output. According to classical theory, if we left this economy to adjust on its own, it would return to full output. Keynesian theory, however, says that some sort of intervention is necessary. Efforts to return output to the full-employment level are known as stabilization policy. There are two types of macroeconomic intervention: fiscal policy, which is the use of government spending and/or taxes to change output, and monetary policy, which is the use of the money supply to change output.

The modern macroeconomic consensus acknowledges that there is some validity to both viewpoints. In the short run, Keynesian assumptions of sticky prices are probably accurate, and at very low levels of output, there is not likely to be much inflation. In the long run, prices have time to adjust and output beyond the full-employment level of output is not possible. Some textbooks present this synthesis in the AD-AS model as an AS curve that contains three ranges, as shown in Figure 16-3. Here, the aggregate supply curve is split into a Keynesian or short-run range, an intermediate range, and a classical or long-run range. If aggregate demand increases in the Keynesian range, there will be increases in output but not inflation. If the aggregate demand increases in the intermediate range, there will be increases in output but also in price level. However, in the classical range, any increase in aggregate demand will result only in increases in the price level.

FIGURE 16-3 • Aggregate Supply Curve with Three Ranges

Let’s return to the AD-AS model that we introduced in Chapter 14. Recall that aggregate demand is made up of the components of GDP (C, I, G, and X - M). Fiscal policy is the use of taxes (which would alter C and I) or government spending (G) to increase or decrease aggregate demand. When a government undertakes expansionary fiscal policy, it either increases government spending or decreases taxes to shift aggregate demand to the right. Increasing aggregate demand increases output, which in turn increases employment, both of which are desirable when the economy is below full employment. However, if the price level is able to adjust at all, it will also increase. One consequence of expansionary fiscal policy is a heightened risk of inflation.

There may also be times when the economy is operating above full employment and inflation is the more serious of the two economic problems. In this case, the government can engage in contractionary fiscal policy by either reducing government spending or increasing taxes. These policies serve to shift aggregate demand to the left and reduce the price level. The trade-off, of course, is that output will decrease and unemployment may increase.

Let’s consider an economy that is initially in long-run equilibrium, but that has a sudden decrease in investor confidence that lowers investment and consumption by $200 billion. If we were to graph this, it would show a decrease in the aggregate demand curve that resulted in an output level that was $200 billion less than the full-employment level, and the economy would have a recessionary gap. If government spending were used to correct this, we could return to our initial equilibrium without causing inflation. However, if we overcorrect, we will go beyond the full-employment level and cause inflation. If we undercorrect, we will fail to return the economy to the full-employment level, and we will have higher rates of unemployment than are ideal.

If we are going to use expansionary fiscal policy, we need to know how much to increase spending or how much to decrease taxes. You might think that this is obvious—if we increase government spending by $200 billion, the aggregate demand curve shifts by that amount, and we are back to equilibrium. However, let’s follow the chain of events when that happens.

Suppose the government initiates a $200 billion spending program that involves building and repairing roads and bridges. In order to do that, the government needs to hire construction workers and buy materials and equipment. That $200 billion then becomes income that households and businesses can either spend or save. That rise in spending would then show up in consumption and shift aggregate demand out even further. The degree to which the aggregate demand curve will shift out further will depend on how much of every additional dollar that they receive people tend to spend or save, also known as the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) and the marginal propensity to save (MPS). Since a consumer can either spend or save additional dollars of income, it must be true that  .

.

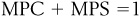

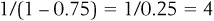

For instance, if people tend to spend 75 percent of each additional dollar and save 25 percent of each additional dollar, the MPC is equal to 0.75 and the MPS is equal to 0.25. To stimulate the economy, the government decides to spend only $100 billion. Table 16-2 goes through the chain of events for the first few rounds of spending that this will spur.

TABLE 16-2 The Multiplier Effect of Government Spending

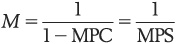

This multiple expansion should look familiar, as it is very similar to the multiple expansion of the money supply from Chapter 15. We calculate the multiplier (M), or the amount of the total change in GDP that results from an autonomous injection of spending, by using a very similar formula for the multiplier:

So, in our case,  . Thus a $100 billion injection will result in a $400 billion increase in GDP, which would push output beyond the full-employment level. Because every new dollar of government spending is multiplied by a factor of 4, we need only $50 billion of fiscal policy to increase GDP by $200 billion.

. Thus a $100 billion injection will result in a $400 billion increase in GDP, which would push output beyond the full-employment level. Because every new dollar of government spending is multiplied by a factor of 4, we need only $50 billion of fiscal policy to increase GDP by $200 billion.

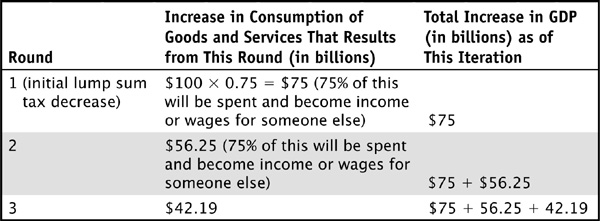

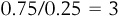

The government can also engage in fiscal policy by reducing taxes. Let’s assume that changes in taxes come in lump sums whereby the government either reduces or increases income taxes by a flat amount. To investigate the impact of this fiscal policy, we need to modify Table 16-2. Instead of the government purchasing $100 billion in labor and materials, the government sends consumers a check (this reduces taxes like receiving a tax rebate) in the amount of $100 billion.

These rounds will continue until someone is trying to spend 75 percent of virtually nothing. The only difference between Tables 16-2 and 16-3 is that the lump-sum tax cut doesn’t inject the entire $100 billion. The multiplier process is immediately smaller because the first round of spending is 25 percent smaller. Thus the tax multiplier (Tm) can be computed as:

TABLE 16-3 The Multiplier Effect of a Tax Decrease

In our example, the tax multiplier would be  . Thus the $100 billion tax cut will increase GDP by $300 billion.

. Thus the $100 billion tax cut will increase GDP by $300 billion.

At first glance, the multiplier effect suggests that fiscal policy is a very promising way to carry out stabilization policy. Unfortunately, that is not the end of the story. Suppose a government has decided to increase government spending to expand output. In order to do that, it must acquire the funds needed to do it in one of three ways: increase taxes, create money, or borrow money. If the government finances an increase in government spending through an equivalent increase in taxes, the net effect on output is going to be much smaller. For example, the previous example showed that a $100 billion increase in government spending will increase GDP by $400 billion. To finance this spending, taxes must be increased by $100 billion, which will reduce GDP by $300 billion. The net effect of this balanced-budget approach to fiscal policy is to increase GDP by only $100 billion. Therefore, there is no net multiplier effect. Some textbooks refer to this as the balanced-budget multiplier, and it is always equal to 1.

If the government creates money to finance the spending, this will cause inflation to increase. When inflation goes up, the power of the multiplier decreases. This is because rising prices mean that, at each round of spending, people are simply paying higher prices for the same consumption, not necessarily increasing consumption.

Finally, there is the possibility of borrowing money. If a government spends more than the tax revenue it collects, it runs a budget deficit. Over time, deficits accumulate to form debt. Just like households and firms, if the government wants to spend more than it earns, it must borrow to do so. This means that deficit spending has an effect on the loanable funds market. Let’s start with the loanable funds market in Figure 16-4 before there is a government borrowing, where $Q0 in funds are loaned out and the market rate of interest is i0. If the government needs to borrow, it joins the other demanders of savings, and the demand for loanable funds increases from D0 to D1. If the original rate of interest remained, the total amount of loanable funds in the economy would be $Q1 (with the government borrowing $Q1 - $Q0 of those funds). However, there aren’t $Q1 worth of savings being supplied when the interest rate is low. Eventually, the interest rate will increase and the total amount of investment will be $QT in equilibrium. Since the difference $Q1 - $Q0 still represents the amount of government borrowing, this means that the amount of private borrowing has decreased to $QP.

The multiplier effect and the crowding-out effect can have competing impacts on GDP. This raises the question about what the final impact on GDP of an increase in government spending will be. The answer will depend on whether the multiplier effect or the crowding-out effect is stronger. For instance, if the multiplier effect is stronger than the crowding-out effect, the shift outward of aggregate demand will be farther than the shift inward of aggregate demand caused by the crowding-out effect, and the final impact will be an increase in GDP, as shown in panel a of Figure 16-6. On the other hand, if the crowding-out effect is strong and the multiplier effect is weak, an increase in government spending can actually wipe out any gains from the government spending, as shown in panel b of Figure 16-6.

FIGURE 16-6 • (a) Multiplier Effect Stronger; (b) Crowding-Out Effect Stronger. AD0 is the initial aggregate demand before government action. AD1 shows the initial effect of government spending. ADM shows the effect on aggregate demand as a result of the multiplier effect, and ADC shows the effect on aggregate demand of the crowding-out effect.

The other type of stabilization policy that can be used is monetary policy, which is the use of the money supply to affect aggregate demand. In Chapter 14, we introduced the liquidity preference model and the role that the money supply plays in determining interest rates. When a central bank increases the money supply, the interest rate decreases, and when a central bank decreases the money supply, the interest rate increases.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve is the central bank. Changes in the money supply are almost exclusively done by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which meets at least eight times per year to set an interest-rate target. To achieve this target, the Open Market Desk of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York buys or sells Treasury securities in the open market in order to achieve the targeted rate. For instance, if the current rate of interest is 4 percent, but the FOMC has decided on a target rate of 4.25 percent, the Open Market Desk will sell bonds until the market rate of interest adjusts to the higher target rate (if bonds are sold, the Federal Reserve is injecting bonds back into the market and taking money out of the money supply). On the other hand, if the Fed wants to lower the interest rate, it will buy Treasuries from the public. When the Fed is an open market buyer of these securities, money is injected into the economy and the securities are taken out. Thus buying Treasuries increases the money supply and reduces the interest rate.

The Federal Reserve also has other tools at its disposal to change the money supply, including changing the reserve ratio or lending through the discount window (overnight lending to banks). However, these options are seldom used, as they do not allow the same kind of control over the money supply that open market operations allow.

By changing the interest rate, the Federal Reserve can moderate the amount of investment in the economy. If the Federal Reserve is engaging in expansionary monetary policy, its goal is to increase aggregate demand by lowering the interest rate, which it does by increasing the money supply. If the interest rate goes down, investment demand goes up, and there is more private investment and consumption. If the Federal Reserve is engaging in contractionary monetary policy, its goal is to decrease aggregate demand by increasing the interest rate, which it does by decreasing the money supply. If the interest rate goes up, investment demand goes down, and there is less private investment and consumption.

This latter point might seem strange, as so far a lot of our focus has been on correcting economic downturns. However, central banks such as the Federal Reserve are charged not just with fighting recessions, but also with ensuring price stability. In general, the goal of price stability is a low and positive rate of inflation.

Consider an economy that is operating beyond full employment, as illustrated in Figure 16-7. Output Y0 is higher than the full-employment level Yf. We know from our analysis of the Phillips curve in Chapter 13 that if the unemployment rate is below the full-employment rate, as it would be here, this places upward pressure on wages and leads to a wage-price spiral. In fact, at Y0, the price level PL0 is higher than it would be if aggregate demand returned to the long-run equilibrium (Pfull). To correct this, the Federal Reserve could sell bonds, which would decrease the money supply from MS0 to MS1, as in panel b of Figure 16-7, and raise interest rates from i0 to i1. An increase in interest rates would lower investment and eventually consumption, which would return aggregate demand back to the long-run equilibrium level of output.

FIGURE 16-7 • Contractionary Monetary Policy

Central banks have a number of criteria for deciding when and why to undertake monetary policy. Some set explicit inflation targets, such as 2 percent annual inflation, and engage in monetary policy in order to achieve that regardless of the output level. The downside to this method, however, is that there are situations in which there are both inflation and a recessionary output gap, and inflation targeting restricts the central bank to only one objective. An alternative method that was suggested by the economist John Taylor takes both inflation and output into account using the Taylor rule. According to this simple equation, the interest rate that the Federal Reserve targets should be as follows:

For instance, if inflation is currently 2 percent and output is 3 percent less than the full-employment rate:

Given the fiscal and monetary tools available, it would seem that policy makers should be able to regulate the economy so that severe recessions and excessive booms (and the inevitable busts that follow them) do not occur, or at least do not become severe. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Neither monetary policy nor fiscal policy can be used to fine-tune the economy. In fact, the implementation of either type of stabilization policy is not without problems.

The Taylor rule actually gives us a clue to one of the problems that monetary policy can encounter. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, the output gap in the first quarter of 2009 was –6.2 percent and the inflation rate was –0.4 percent (meaning that there was a brief period of deflation). This would imply that the Federal Reserve should set a target of –2.7 percent, a negative and therefore impossible rate of interest (a real interest rate of zero is loaning money for free; a negative interest rate would be paying somebody to borrow money from you). In fact, the federal funds rate has been between 0 percent and 0.25 percent since early 2009. Even if it wanted to, at this point the Federal Reserve could not use monetary policy to expand aggregate demand, a problem known as a liquidity trap. Monetary policy has been rendered ineffective because the interest rate is up against the lower bound of zero.

An additional problem with monetary policy, and with fiscal policy as well, is that both suffer from lags. The first category of lags is called inside lags, which is the time taken between recognizing a problem and taking action. Outside lags are the length of time before an action has its full impact on the economy. While both monetary theory and fiscal policy suffer from policy lags, each is affected differently by different aspects of the lags.

A recognition lag is an inside lag that refers to the time it takes to recognize that there is a problem. Unemployment and inflation data that are produced this month are actually a report of what was happening in the previous month. In fact, unemployment data themselves tend to reflect conditions that may have existed for quite some time (for instance, firms may wait to see if a downturn is temporary before laying off workers).

Decision lag refers to the length of time it takes for an action to be chosen. Fiscal policy has a significant disadvantage in terms of this lag. Monetary policy decisions are made routinely, and the FOMC can call special meetings to make changes if the committee agrees on the urgency of a situation. Fiscal policy, however, is subject to the legislative system. If policy makers want to engage in discretionary fiscal policy (that is, changes in government spending that require specific action), the wait can be very long indeed as bills are debated in Congress, revised, redebated, and voted on. For this reason, much of the fiscal policy that is used routinely is in the form of automatic stabilizers. These are provisions in the tax code and transfer payment systems that change without the need for any additional legislative action. For instance, when the unemployment rate goes up, the amount of transfer payments for unemployment insurance increases and progressive income taxes decrease, which help to offset the effects of a recession.

Finally, the impact lag or outside lag is the length of time required for the action to work its way through the economy. For instance, monetary policy may not suffer from as severe a decision lag as fiscal policy, and implementation of monetary policy is fairly rapid (trades usually occur the same day, and the interest rate starts to adjust as soon as this occurs). However, it may take a while to change investment strategies to take the new interest rate into account. Finally, any multiplier effect will also take time to work its way through the economy. These lags are significant drawbacks of any kind of stabilization policy. Because the time between recognition and impact can be significant, economic conditions may improve (or worsen) on their own, making the action chosen inappropriate.

Another important distinction is that these policies are not effective at changing output or unemployment in the long run. Stabilization policy can really only return an economy to the full-employment rate of output, not stimulate economic growth. Economic growth is an increase in the ability to produce more goods and services, as reflected by an increase in the long-run aggregate supply curve. The consensus in macroeconomics is that monetary policy and fiscal policy are not very effective at changing this in the long run.

Let’s walk through a few different scenarios that we might see in our AD-AS model and determine what impact monetary and fiscal policy might have. Before we do, however, we must remember that policy makers always have the option of taking no action at all. An economy may stabilize (that is; return to the full-employment level of output) on its own. However, this may take so long to occur that it is unpleasant or politically destabilizing, such as extended levels of high unemployment. The economist John Maynard Keynes referred to this problem with his statement, “In the long run we are all dead.” In each of our scenarios, we start with an economy in long-run equilibrium where our initial aggregate demand AD0 intersects our initial short-run aggregate supply SRAS0 at the full-employment level of output Y0 and a price level PL0.

First, let’s consider a familiar example: a recessionary gap caused by a downward shift in aggregate demand from AD0 to AD1. This could be caused by declining expectations, declining wealth, a decline in net exports (more on this in the next chapter), or declining investment spending. As a result, output decreases and the price level decreases. If nothing is done, wages will adjust downward, and the short-run aggregate supply curve will shift outward from SRAS0 to SRAS1, returning the economy to full output, but at a permanently lower price level (that is, with deflation, which can be painful), as shown in Figure 16-8a. If policy makers wanted to intervene, they could use fiscal policy by increasing government spending or decreasing taxes. They could also use monetary policy, increasing the money supply, lowering the interest rate, increasing investment, and shifting aggregate demand to the right back to AD0. They could also use some combination of the two. Figure 16-8b illustrates the result of either fiscal or monetary policy: output returns to the original price level and the original output level.

FIGURE 16-8 • (a) No Policy Action Taken; (b) Either Expansionary Monetary Policy or Expansionary Fiscal Policy Used

Next, let’s consider an inflationary output gap. Figure 16-9 illustrates an inflationary gap caused by an increase in aggregate demand. Again, policy makers may choose to do nothing. In this case, prices will eventually adjust—for example, the lower rate of unemployment will drives up wages. In the end, SRAS shifts leftward and output returns to the full-employment level, but there is now a permanently higher price level, as shown in Figure 16-9a. Instead, policy makers could undertake contractionary fiscal policy by decreasing spending or raising taxes. The central bank could use contractionary monetary policy by selling bonds, lowering the money supply, raising interest rates, and lowering investment. In either case, aggregate demand will return to AD0 from AD1 and there will not be a permanent increase in the price level (see Figure 16-9b).

FIGURE 16-9 • (a) No Policy Action Taken; (b) Either Contractionary Monetary Policy or Contractionary Fiscal Policy Used

Finally, let’s consider the special case of supply-induced inflation. This can result when there is a sudden increase in the price of inputs, as happened during the recession in the 1970s, or any other negative supply shock. We show the effect of this on the AD-AS model in Figure 16-10. As you can see, we have the worst of all worlds: stagnant GDP and inflation (a combination known as stagflation). If policy makers allow the economy to self-adjust, short-run aggregate supply will return to the initial level as price adjusts. However, policy makers face a dilemma—any action that they take to increase output and lower unemployment will result in a permanently higher rate of inflation.

FIGURE 16-10 • (a) No Policy Action Taken; (b) Either Expansionary Monetary Policy or Expansionary Fiscal Policy

Questions that ask you to trace the chain of events when monetary policy and fiscal policy are used to stabilize an economy are a favorite of instructors. As you get practice tracing through the process, it will be helpful to always follow these steps:

1. Start with an initial point. The question you are given will give you a starting point. There are usually five possibilities for these: long-run equilibrium, an inflationary gap, a recessionary gap, stagflation, or a supply-induced increase in output.

2. Figure out the key event. The question might then ask you what kind of policy should be undertaken. For instance, an economy that starts in long-run equilibrium may enter a recession or an inflationary period, or a government may engage in expansionary fiscal policy.

3. Figure out the effect of the key event on the AD-AS model. For instance, if the key event is expansionary fiscal policy, you should show that in your AD-AS model and figure out what the effect is on output, employment, and the price level.

4. Figure out if there are any secondary or long-run effects of the event. For instance, if the price level changes, this may have an impact on foreign exchange. We examine this possibility in Chapter 17.

5. Apply the correct fiscal and/or monetary policy to the outcome of the key event. If you know that inflation is becoming a problem, you would prescribe a contractionary policy to reduce AD and relieve the upward pressure on prices.

In this chapter, we discussed the important role that private investment plays in the business cycle. Small changes in investment can lead to large changes in output, employment, and the price level. Because of this, macroeconomic stabilization has a lot to do with the interest rate. If fiscal policy is used to stabilize the economy, government spending and tax rates change aggregate demand through a multiplier effect, but this may be offset by the effect that government borrowing has on the loanable funds market. Monetary policy does not suffer from the same problem, as it targets interest rates directly. However, it may face the problem of a liquidity trap. Both monetary and fiscal policies suffer from lags that may lessen their effectiveness in managing economic fluctuations. This does not imply, however, that stabilization policies should never be attempted, as allowing the economy to self-adjust may sometimes be long and painful. We concluded this chapter with examples of how monetary and fiscal policy affects the AD-AS model. In many of our examples so far, we have assumed a closed economy. We drop this assumption in Chapter 17 and explore how these models change when we allow for international trade.

For each of the following, choose the answer that best fits.

1. Although_____makes up the largest category of GDP in the United States, changes in_____are responsible for most recessions and expansions.

A. investment; net exports

B. investment, consumption

C. consumption, investment

D. government spending, net exports

2. The crowding-out effect refers to:

A. Decreases in the demand for loanable funds that occur as a result of government deficit spending.

B. Decreases in the amount of private investment that occur as a result of government deficit spending.

C. Decreases in the demand for loanable funds that occur as a result of expansionary monetary policy.

D. Decreases in the amount of private investment that occur as a result of expansionary monetary policy.

3. Which of the following is associated with the classical theory of macroeconomics?

A. A vertical aggregate supply curve

B. A horizontal aggregate supply curve

C. An upward-sloping aggregate supply curve

D. A role for activist fiscal policy

4. Which of the following is associated with the Keynesian theory of macroeconomics?

A. Sticky prices below full employment

B. A horizontal aggregate supply curve below full employment

C. A role for activist fiscal policy

D. All of the above

5. Suppose the marginal propensity to save is 0.4. The final impact on GDP of a $100 billion injection of government spending will be:

A. GDP will increase by $250 billion, regardless of the crowding-out effect.

B. Less than $250 billion, depending on what the crowding-out effect is.

C. GDP will increase by about $166 billion, regardless of the crowding-out effect.

D. Less than $166 billion, depending on what the crowding-out effect is.

Refer to Figure 16-11 for questions 6 through 8.

FIGURE 16-11

6. The movement shown from point A to point B could best be explained by:

A. A decrease in wealth

B. An increase in wages

C. An increase in investment

D. An increase in optimism

7. If an economy moved from point C to point B, which of the following would be an effective method of returning to full employment?

A. Decreasing government spending

B. Selling bonds

C. Buying bonds

D. Increasing the tax rate

8. Suppose the economy moved from point A to point B. If policy makers engage in expansionary fiscal policy, which of the following is likely to occur?

A. Output will return to full employment, and the price level will remain unchanged.

B. Output will return to full employment, and the price level will increase.

C. Output will increase beyond full employment, and the price level will decrease.

D. Output will decrease further, and the price level will increase.

Answer questions 9 and 10 as indicated.

9. Consider the economy of Ame, which is in long-run equilibrium. As a result of a decline in the value of homes, household wealth decreases.

I. Indicate the effect of this action on output and price level, using an AD-AS curve.

II. You are the head of the central bank of this country. Describe what kind of stabilization policy you should pursue. Assuming your job is similar to that of the head of the Federal Reserve, how will you accomplish this?

III. Show the effect of your action on the appropriate market.

IV. Show the effect of your action on the AD-AS model.

V. What situation might make it impossible for you to take any action?

10. Consider the economy of Ema, which is experiencing stagflation.

I. Show the current situation in Ema using an AD-AS model.

II. What kind of event could have caused this?

III. Suppose that the government of Ema has determined that the government spending multiplier effect in Ema is 4. What is the marginal propensity to consume in Ema?

IV. Suppose the government of Ema is studying whether the multiplier effect or the crowding-out effect is stronger. What kind of policy is it contemplating?

V. The government of Ema has decided to undertake the policy action being considered in part IV. On the AD-AS model, illustrate the impact of the policy on output and price level. State what will happen to the level of unemployment.