When the price of one or two things goes up, we notice. Whether we are paying more for gasoline or for a pizza, when the price of something we want to buy goes up, it makes us feel poorer. But what happens when the price of everything goes up? Are we even worse off? The answer to this might be surprising.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. Explain the Consumer Price Index.

2. Define and calculate inflation.

3. Explain some of the problems that inflation may cause.

4. Explain the difference between deflation and disinflation.

5. Describe a theorized relationship between inflation and unemployment.

In Chapter 6, we talked about the equilibrium price of a single good or service in a single market. In macroeconomics, however, we are talking about all the goods and services that an economy produces. The corollary in macroeconomics is the price level, the average of all the prices of goods and services in an economy. Inflation is an increase in that price level, meaning that when inflation occurs, prices in general are going up.

Another way to think about inflation is not just that prices are going up, but that the value of money is going down. Consider an economy that has only one good—oranges. If the price of an orange is 20 cents, then the value of a dollar is 5 oranges (because that is what you can actually buy with a dollar). However, if the price of oranges goes up to 25 cents, the value of a dollar falls to 4 oranges.

We respond when the price of a single thing increases. Would it make sense that we would really respond if the prices of all things were increasing? Interestingly, the answer is, not necessarily. Recall from Chapter 11 that one of the prices that firms must pay is wages. If all prices are going up, firms are paying higher wages, which means that households are receiving higher incomes. In other words, if prices double, but so do incomes, nobody is any poorer or any wealthier in terms of his buying power.

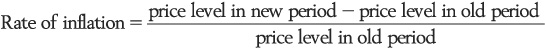

What is important, however, is the rate at which the price level is changing. The rate of inflation is the percentage increase in prices from one period to another. To find the rate of inflation between two periods, we calculate:

So what exactly do we mean by a price level? A price level is some sort of measure that is meant to capture the overall prices in an economy at some point in time. There are actually several different measurements that are calculated that fit that description, but the one that most people are most familiar with and that is most widely used in the United States is the Consumer Price Index (CPI). To understand the CPI, let’s break down what the term means:

Consumer. The CPI is designed to include the goods and services that a typical consumer purchases.

Price. The CPI uses the prices that consumers actually pay for those goods and services.

Index. The prices paid for the goods and services are converted into a tool that simplifies them by showing them as movements of a numerical series. In other words, the CPI takes the prices and compares them to prices during some base period to make them easier to understand and compare.

In the United States, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) calculates the CPI. In order to calculate a CPI, you must complete five steps:

1. Fix a basket of goods. In order to see how prices are changing over time, we need to limit our focus to changes in the prices, not in the goods being purchased. For this reason, we need to figure out what should go into our basket of goods and always look at the prices that are paid to purchase exactly the same goods. The BLS creates a basket of goods based on surveys of thousands of households to determine what people actually buy and the quantities that they buy.

2. Find the prices. The next step is to determine the retail price of each of these goods and services. Each month, BLS employees call stores and firms to determine these prices. In some cases, BLS employees will walk through supermarkets and scan product bar codes to get the pricing information directly into the BLS database.

3. Compute the cost of the basket in each period. Once the prices of all those goods are determined, they are added together to determine the amount of money it would take to purchase the basket of goods.

4. Choose a base year. It doesn’t matter which year you choose, but keep in mind that you are comparing all years’ prices to this year. In fact, the CPI occasionally changes the base year it uses and then recalculates the CPI for all years based on a new base year.

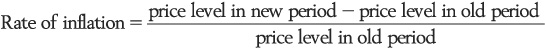

5. Compute the CPI. To calculate the CPI for a particular year, say year X, the following formula is used:

The cost of purchasing the market basket in any given year is then compared to what it cost to purchase that basket in the base year. Currently, the BLS actually uses the average price over a three-year period, 1982–1984, to compute the cost of the basket in the base year.

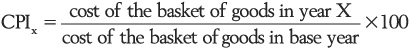

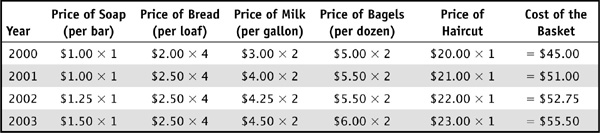

Let’s use an example to show how this is done. Suppose the nation of Cire conducted a survey and concluded that each month the typical household purchased 1 bar of soap, 4 loaves of bread, 2 gallons of milk, 2 dozen bagels, and a haircut. A survey of sellers found out that each of these goods sold for the prices in Table 13-1 during a four-year period.

TABLE 13-1 Prices in Cire, 2000–2003

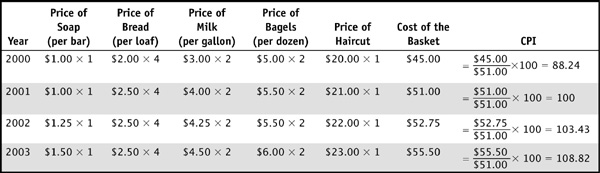

We can then use this information to calculate the price of a basket in each year (see Table 13-2).

TABLE 13-2 Cost of Basket of Goods in Cire

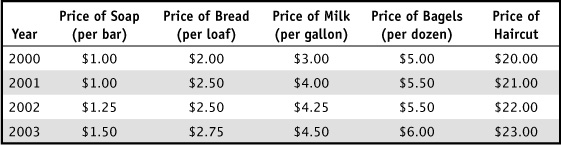

The next steps are to choose a base year and then calculate the CPI for each year. Let’s use 2001 as our base year (see Table 13-3).

TABLE 13-3 CPI for Each Year in Cire, Using 2001 as Base Year

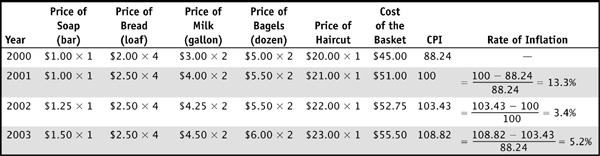

Finally, we can use the CPI to calculate the rate of inflation (see Table 13-4).

TABLE 13-4 Rate of Inflation in Cire

There are a couple of things that you should note immediately from these calculations. First, the CPI in the base year is always 100. Second, whenever you are comparing the CPI for future years (that is, when the CPI is over 100) to the base year, the rate of inflation since that base year is easy to calculate. For instance, the rate of inflation between 2001 and 2003 was 8.82 percent.

In Chapter 11, we discussed how GDP is really the product of prices and output. You take the quantity of output in a given year (Q) and multiply it by the price of the output (P) in that year. Suppose that next year prices rise, but Q stays the same. Clearly GDP will increase, but this is misleading because the true size of the economy hasn’t increased; it has simply experienced inflation. The value of the output this year, using this year’s prices, is called nominal GDP.

To adjust for changing prices (inflation) from year to year, we adjust nominal GDP by calculating the value of current production, but using prices from a fixed point in time—the base year. Once this adjustment is made, we have real GDP. For example, if we value 2010 production at 2009 prices, we have computed real GDP in 2010, and now we can compare it to production in 2009 (the base year) because we have held the prices constant. This is also known as “constant-dollar GDP.” If real GDP is higher in 2010 than it was in 2009, then we can say that, even after adjusting for inflation, the value of the nation’s output has risen.

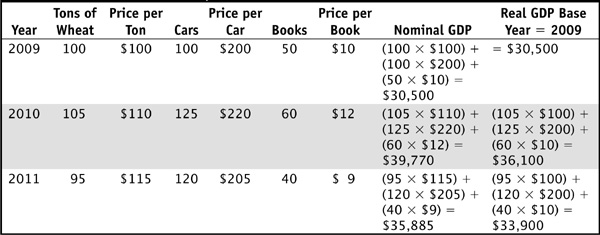

Suppose an economy produces only three goods. Table 13-6 shows hypothetical prices and output levels for three recent years.

TABLE 13-6 Real GDP for an Economy

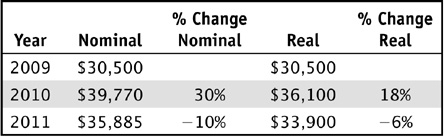

If we focus only on the nominal GDP column of the table, we can see that there was a large jump from 2009 to 2010 and a decrease from 2010 to 2011. But we can’t determine whether these changes were due to changes in production or changes in price. In reality, both factors are changing. We eliminate the price differences by using the prices from 2009 as our base year prices and computing the column of real GDP. Table 13-7 converts these dollar figures into percentage changes.

TABLE 13-7 Percentage Changes for Table 13-6

The large jump in nominal GDP from 2009 to 2010 doesn’t look so impressive when we adjust for the inflation that occurred. Likewise, the large decrease in nominal GDP from 2010 to 2011 isn’t as large when we account for the fall in prices that occurred in 2011.

This is just one example of how to deflate nominal results to get the real values of GDP. There is also a tool called the GDP deflator, which is a number that modifies nominal GDP to get real GDP. The GDP deflator is sometimes used rather than the CPI to get real GDP in a given year because the CPI does not capture changes in the prices of all goods, only consumer goods. The technique, however, is the same.

In our example, we haven’t really said anything normative about the prices going up from year to year. If the households of Cire are seeing similar increases in income from year to year, they aren’t really any worse off. There are, however, some costs associated with inflation, which is why rapid inflation is generally viewed as being undesirable.

First, inflation is associated with shoe-leather costs. This funny-sounding term actually refers to the transaction costs of inflation. When prices go up, the value of the dollar goes down. Because of this, people will go out of their way to avoid holding money in their wallets, and will go out of their way to store value either in goods or in a bank account that is earning enough interest so that money keeps its real value. For example, during the hyperinflation that Germany experienced in the early 1920s, people would get paid daily and would immediately rush out to spend their money on goods before the money became worthless. The term shoe-leather costs is a reference to the wear and tear that people would put on their shoes in carrying out these transactions, when the running around that they were doing to avoid the loss of value of their money could have been put to productive use.

Second, inflation imposes menu costs. In a modern economy, there are many goods and services, each with a different price. When prices are changing, each of these prices has to be changed. Consider a restaurant menu—if prices are changing every day, someone must go and change the prices in the menu every single day, and the time spent doing that is not going toward a productive use.

Interestingly, there are winners and losers from inflation. When people borrow money, the borrower and the lender enter into a contract that specifies the amount borrowed, the time period in which it must be repaid, and the interest rate that will be charged to the borrower. The interest rate that is actually charged, called the nominal interest rate, is set so that it takes into account the expected rate of inflation over the time period of the loan and the lender also gets some sort of real payment for agreeing to lend the money (the real interest rate). For instance, if the expected rate of inflation is 5 percent and the nominal interest rate is 8 percent, the amount that the lender actually gets is 8 percent − 5 percent = 3 percent.

What happens if the rate of inflation turns out to be 6 percent? In this case, the lender loses out—it expected to make a 3 percent return, but it made only 2 percent in real terms. On the other hand, if the inflation rate turns out to be only 4 percent, then the borrower is worse off. If there is any uncertainty regarding inflation, people might be reluctant to enter such contracts. When there is a great deal of price volatility, or when inflation is very high (which leads to unpredictability), this can discourage investment or borrowing.

If inflation is undesirable, then would deflation (a decrease in the price level or a negative inflation rate) be a good thing? The consensus is a resounding no, for several reasons. First of all, if people expect prices to fall, they may put off spending. For instance, if you know that you will have to pay only half as much for a car in six months, it makes sense to put off that purchase. However, as we will see in the next chapter, this reduction in spending puts a halt on the circular flow of goods and services.

Second, if prices are going down, the value of a dollar in the future is increasing. While that sounds good, it also means that the value of debts that are owed increases. Lenders gain from deflation because, when they are repaid by the borrowers, those dollars are worth more, not less. Of course, this means that the borrowers are hurt by this transfer of purchasing power and rising debt burden. If there is a widespread increase in the amount of debt that is owed, this may lead to increases in bankruptcies and to bank failures. (This is precisely what happened during the deflation that the United States experienced during the Great Depression.)

Finally, if prices are going down, wages will go down as well. Unfortunately, wages do not go down very easily, as people are usually reluctant to agree to work for less money. This means that sometimes the only way to lower wages is through mass unemployment. For these reasons, deflation is usually associated with severe recessions and depressions.

Disinflation, on the other hand, is something that might be desirable during periods of rapid inflation. Disinflation is a slowing of the rate of inflation—for instance, if the inflation rate had been 15 percent per year and it is brought down to 5 percent. In other words, disinflation is a lower rate of inflation. Disinflation can be a long and costly process, in terms of employment and output. This is especially true if expectations of high inflation have become ingrained in an economy.

In 1958, an economist named William Phillips published a paper in the journal Economica that noted that when the unemployment rate in Great Britain was high, the inflation rate was low, and when the inflation rate was high, the unemployment rate was low. This inverse relationship between the inflation rate and the unemployment rate came to be known as the Phillips curve. The implication of this in terms of disinflation is clear: one of the costs of disinflation may be increasing the unemployment rate.

This trade-off between unemployment and inflation has an intuitive explanation. If the unemployment rate is very low, this will cause upward pressure on wages, leading to the cycle we described at the beginning of this chapter. Indeed, during the 1960s, economists came to believe that this was a real tradeoff that policy makers had to consider. However, in the 1970s, this relationship appeared to fall apart as economies experienced both high inflation and high unemployment. What happened?

The culprit turns out to be expectations. Up until the 1960s, people had come to expect low inflation. By the late 1960s, inflation had begun to increase, and persistent inflation became the norm. Once employees and firms begin to expect inflation, they will incorporate these expectations into employment contracts. For instance, if firms and employees expect that there will be 3 percent inflation, they will agree to wages that are 3 percent higher. This means that the actual rate of inflation that is experienced at any given unemployment rate will be 3 percent higher.

This is illustrated in Figure 13-1. The short-run Phillips curve (SRPC) shows the relationship between unemployment and inflation for a particular country. When this country experiences 7 percent unemployment, it experiences 0 percent inflation. Suppose the government of this economy decides that it wants to lower the unemployment rate to 4 percent, which it achieves through a variety of policies. This will drive up the inflation rate to 3 percent.

FIGURE 13-1 • Effects of Attempting to Lower Unemployment, as Shown by the Short-Run and Long-Run Phillips Curves

Over time, employees and firms will come to expect this amount of inflation and begin incorporating this into their wages. By doing this, they will make the actual rate of inflation 3 percent higher, even at the same rate of unemployment. This effect is illustrated by the shift from the initial SRPC0 to SRPC1. Note that now people will come to expect 6 percent inflation, and will build these expectations into their wage negotiations. As a result of attempting to trade off lower unemployment for higher inflation, there will be continuously accelerating rates of inflation. If this economy wanted to create disinflation, it would have to simultaneously increase unemployment and lower expectations of inflation, which could be a difficult and painful process.

On the other hand, if no attempt had been made to lower the unemployment rate below 7 percent, there would be no expectation of inflation. In the long run, after expectations have time to adjust to the inflation that an economy actually experiences, we end up with a single rate of unemployment that would not be associated with ever-accelerating inflation. The long-run Phillips curve (LRPC) reflects the relationship between inflation and unemployment once expectations have adjusted. It is vertical at the nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU).

The implication of this is clear: if an attempt is made to maintain a level of unemployment below the NAIRU, the result will be ever-escalating levels of inflation. Recall from Chapter 12 the concept of the natural rate of unemployment. The NAIRU and the natural rate of unemployment are one and the same.

Inflation is an increase in the general level of prices in an economy. This chapter discussed the final statistical measure of the economy that we will consider, the Consumer Price Index, which captures the rate of inflation in an economy. The CPI is a measure that tracks the cost of purchasing a basket of goods that a typical urban household purchases. Unexpectedly high rates of inflation impose costs upon society and create winners and losers. There has been an observed inverse relationship between the level of inflation and the level of unemployment, and attempts to maintain a level of unemployment that is “too low” can result in ever-increasing amounts of inflation. That leads us to the question, what is the “right” amount of unemployment? Recall that unemployment and production are tied to each other. If more goods and services are produced, more workers are employed to produce those goods and services, and there is less unemployment. This implies that there may be some equilibrium level of output. We return to this idea of production in the next chapter, when we explore not the supply and demand for a single good, but the supply and demand for all goods and services in an economy. This model of aggregate supply and aggregate demand allows us to predict how the price level and unemployment can change in the macroeconomy.

Is each of the following statements true or false? Explain.

1. Deflation is a desirable alternative to inflation.

2. The Consumer Price Index measures the increases in prices of all goods and services produced in an economy.

3. To calculate the rate of inflation between any two years, you subtract the CPI in one year from the CPI in the previous year.

4. The rate of inflation from year to year will not change significantly if you change the base year, but the values of the CPI in each year will change.

5. When the rate of inflation is higher than expected, borrowers are better off and lenders are worse off.

Give a short answer for each of the following questions.

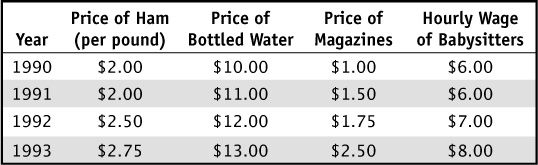

For questions 6 through 8, consider the following facts about the Nation of Maxistan. The typical consumer in Maxistan consumes a basket of goods consisting of 2 pounds of sliced ham, 1 case of bottled water, 6 magazines, and 4 hours of babysitting. A survey of prices for a four-year period is given in Table 13-8.

6. Calculate the cost of the basket of goods for each year.

7. Using 1990 as the base year, calculate the CPI for each year.

8. Calculate the rate of inflation for each year.

For questions 9 and 10, consider the graph in Figure 13-2.

FIGURE 13-2

9. What level of unemployment is associated with the natural rate of unemployment for this economy?

10. The nation is currently experiencing 4 percent unemployment and expects 2 percent inflation. Given this expectation and the shift in the SRPC shown in Figure 13-2, what was the actual rate of unemployment and inflation that this economy experienced in the short run?