Unemployment, like GDP, is an important indicator of the health of the macroeconomy. In order to make the goods and services that a country produces, firms need workers. All else equal, then, we expect more people to be working when an economy is making more goods and services and fewer people to be working when an economy is making fewer goods and services. Thus, it’s intuitive that the number of people working, or rather not working, can be a good indicator of how close an economy is to producing its full potential. While everybody is familiar with the idea of the unemployment rate, many people lack a real understanding of what unemployment is, how it is measured, how to interpret it, and the caveats we need to consider in drawing conclusions about it.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. Understand what the labor force is and calculate the labor force participation rate.

2. Describe the term unemployment and how to calculate the unemployment rate.

3. Describe the differences between structural, frictional, seasonal, and cyclical unemployment.

4. Describe three theories on why labor markets fail.

5. Describe what is meant by full employment and the natural rate of unemployment.

6. Understand what is meant by underemployment and discouraged workers.

When reporters, politicians, and pundits talk about the state of the economy, one of the numbers that they are likely to hold up as a sign of its success or failure is the degree of unemployment that exists in an economy. Unemployment refers to a situation in which people are not working, even though they are willing and able to work.

These two italicized words are an important clue to understanding what we mean by unemployment. It is not merely everyone who is not working. For instance, if a family decides that one parent will stay home and take care of the kids while the other parent works, and both parents are happy with this situation, we would hardly think of the nonworking parent as being a reflection of a bad state of the economy. When we talk about unemployment, we are really talking about a person who wants to work but for some reason is unable to find work.

Despite the ubiquity of unemployment reports, it is easy to argue that most people still do not understand unemployment very well. We tend to think of unemployment as “bad.” Unemployment can be a difficult, painful time for those who are experiencing it, and the existence of unemployment may even represent a market failure. However, a certain amount of unemployment not only is good for an economy, but may be necessary if that economy is to grow at a healthy pace without large increases in the prices of goods and services.

Before we start to calculate who should (and should not) be counted as unemployed, we need to limit ourselves to people who might possibly be employed. This might seem silly—shouldn’t everyone be counted? Of course not. Remember, ultimately we want to capture the extent to which the market for labor is failing. We don’t want to include people in our count who wouldn’t be participating in this market even if it operated perfectly. If we counted three-year-old children, stay-at-home parents, or people in prison as potential workers, this could seriously distort a measure of who is willing and able to work.

Before we continue on to our measures of work, we need to identify the agency that is responsible for producing these measures. In the United States, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has collected and analyzed employment data since 1940. Each month, the BLS conducts the Current Population Survey (CPS) in order to track trends in employment and the labor force. All of the statistics included in this chapter are from annual CPS reports.

Those who are considered potential workers are called the labor force. The definition of those included in the labor force varies by country, but in the United States, to be counted as being in the labor force, you must:

• Be of working age (over 16 years)

• Not be part of the “institutionalized population” (that is, not be in prison, jail, a mental institution, or the military)

And have either:

• Worked at least one hour in the previous week or

• Not worked at all in the previous week and been actively looking for work

As of July 2011, there were 153.2 million people in the U.S. labor force. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the U.S. population in July 2011 was approximately 307 million people. Thus, roughly half of the U.S. population isn’t counted as potential workers.

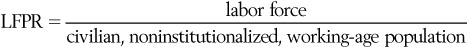

This leads us to our first measure of the health of a nation’s labor market, the labor force participation rate (LFPR). The LFPR tells us the percentage of the population that is participating in the labor market, either by working or by trying to get a job. To find the LFPR, we simply divide the labor force by the civilian, noninstitutionalized, working-age population:

The LFPR can tell us much more than a simple percentage. First, it can tell us how the full employment rate of an economy is changing over time—the more people who are participating in the labor force, the more potential for jobs there is over time (we will discuss this more in Chapter 14). Second, it can also indicate changes in the composition of the labor force over time. If people tend to stay in school for longer periods of time, or if large numbers of the population are incarcerated or in the military, this will lower the LFPR. On the other hand, if more people are drawn into the workforce because there are better opportunities available to them or because incomes are increasing, the LFPR will increase.

As of July 2011, the U.S. LFPR was 63.9 percent. For the past 30 years or so, the labor force participation rate in the United States has hovered around 64 to 67 percent. However, in the 1940s, the LFPR was only around 48 percent. The majority of this dramatic increase is due to the increased labor force participation by women as single-earner; two-adult households have become the exception rather than the norm.

Every month, on the first Friday of the month, the BLS releases the monthly unemployment rate, the percentage of people that were unemployed during the previous month. Ultimately, the purpose of the unemployment rate is to capture the true employment situation. An important question for a nation is this: are the people who are willing and able to work able to find jobs? The higher the unemployment rate is, the more likely it is that the answer to that question is no.

Our measure of unemployment should therefore focus on those who are willing and able to work. Just as the labor force doesn’t include people who have no interest in working or no ability to work, we don’t want to count people who don’t have a job, but aren’t really trying to get one, as unemployed. Therefore, we define employed and unemployed as follows:

Employed. A person is counted as being employed if he worked a single hour during the previous week

Unemployed. A person is counted as being unemployed if he did not work a single hour during the previous week and had actively looked for work during the last four weeks.

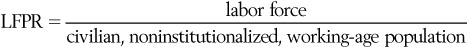

Taken together, the employed and the unemployed make up the entire labor force. To calculate the unemployment rate (UR), we simply divide the number of people who are unemployed by the total number of people in the labor force:

For example, in July 2011, there were 139.3 million people employed in the United States and 13.9 million people unemployed. This gives us a labor force of 153.2 million and an unemployment rate of 9.1 percent.

There is a third category used by the BLS to describe people above the age of 16 who are neither employed nor unemployed. These folks are classified as “not in the labor force” and include retirees, stay-at-home parents, and other adults who have simply chosen not to seek work or who physically cannot work. The extent of a special subset of this last group of people, the so-called discouraged workers, is something that warrants additional discussion a bit later in the chapter.

The unemployment rate tells us the percentage of people who are actively looking for work out of all of the people in the labor force. But without some additional information, we can’t really interpret this number. If some unemployment is good and too much unemployment is bad, what is the “right amount” of unemployment? To better understand that, we need to discuss the different types of unemployment.

Still Struggling

Still Struggling

Consider the fictional economy described in Table 12-1, in which it is illegal for those under the age of 16 to work and the mandatory retirement age is 65.

TABLE 12-1 Maxistan Annual Census

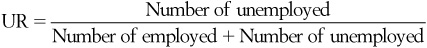

There are a total of 100,000 people in Maxistan, and 70,000 of them are between the ages of 16 and 65. However, we need to remove those who are institutionalized (2,000) and those who are in the military (6,000). That leaves us with 62,000 who are in the civilian noninstitutionalized working-age population (CNIWAP).

The labor force consists of those who are employed (35,000) and those who are unemployed and looking for work (4,000). Therefore, the labor force (LF) = 39,000.

The labor force participation rate =  percent.

percent.

There are 4,000 people who are not currently working but are looking for work. The unemployment rate = unemployed/LF =  percent.

percent.

The reason we tend to think of unemployment as being undesirable is that we tend to think of it in terms of losing a job or having trouble finding one; in other words, it is the involuntary nature of unemployment that we dislike. This is a valid point: an economy that cannot provide jobs for everyone who desires one has problems. However, not all unemployment is involuntary. We can divide unemployment between these two concepts. Economists generally categorize unemployment as being either frictional unemployment or structural unemployment.

Frictional unemployment, just as it sounds like, occurs when the labor market doesn’t work perfectly. Basically, frictional unemployment is unemployment that results from the fact that people aren’t perfectly matched with jobs. This can happen when someone quits a job that she doesn’t like in order to find another one, someone is holding out for a job offer with a higher wage, or someone is fired for cause (that is, he wasn’t good enough at his job). Generally, frictional unemployment exists because of the costs involved in matching workers with jobs, rather than because of some fundamental problem with the economy. In this sense, a certain amount of frictional unemployment is actually healthy for an economy—it takes time for people to find appropriate jobs for their skills. If they just took whatever job first became available, they might be poorly matched to that job and thus be less productive than they should be.

Structural unemployment is unemployment that is caused by an inherent mismatch between the skills that employers are demanding and the skills that workers can provide. This is generally involuntary unemployment (whereas frictional employment can really be either). For instance, when demand for a particular skill permanently declines (like blacksmithing, for example), workers with that skill will not be able to find employers that are willing to hire them. The mismatch may also be due to the seasonal nature of the work. Some types of work, such as agricultural work or construction, occur only at certain times of the year, and when the season is over, those workers become unemployed (this is known as seasonal unemployment). As we discussed in Chapter 10, the demand for labor is based on firms’ expected demand for their goods. If firms expect that future sales will be bad, they may not hire workers or they may even eliminate jobs. If we extend this to the economy as a whole, whenever an economy contracts as part of the business cycle, workers tend to lose their jobs and have trouble finding new ones, a problem known as cyclical unemployment.

The unemployment rate is a good approximation of the labor situation in a country, and it is an indicator that a country is either underproducing or overproducing goods and services. Suppose a country has a potential working population of 5,000, with 1,000 of those people not being in the labor force and 250 being unemployed. This means that the labor force is 4,000, there are 3,750 people employed, and the unemployment rate is 6.25 percent.

Suppose we knew that this economy was capable of producing $200 billion worth of goods and services, and that it takes exactly 3,750 workers to produce that amount of goods and services. In this case, this economy has just the “right” amount of unemployment. The term full employment refers to the situation in which an economy is fully utilizing its labor force to the extent that is supported by the other factors of production that it employs. There is therefore a natural rate of unemployment, that is, a level of unemployment that we would expect to see even when the economy is operating at its full potential. For the fictional nation just described, the natural rate of unemployment is 6.25 percent. If the unemployment rate were to rise above 6.25 percent, we might conclude that the state of the economy is weakening, total production is falling, and the economy may be slipping into a recessionary period. If the unemployment rate were to fall below 6.25 percent, we might conclude that the economy is actually producing more than its capacity, which could lead to a spike in prices and an inflationary period. We will discuss the causes and ramifications of recessionary and inflationary periods in Chapter 14.

While the unemployment rate is a good approximation of the state of the labor situation in a country, it is not a perfect measure. In fact, in certain situations, it can even be somewhat misleading. For that reason, we sometimes need to get a bigger picture of the employment situation than merely the unemployment rate in order to draw conclusions about the labor market.

One example of this is the idea of underemployment. This term applies to the situation in which people take jobs for which they are overqualified and/or jobs with reduced hours when they cannot find appropriate jobs. Consider a person who has been looking for a job for a long time in the field she has trained in, such as a kindergarten teacher. However, she may find that a job in the field she trained in is not available, and she may need to take a lesser job, like one in a coffee shop, or one with fewer hours, like one as a teacher’s aide, to get by until she finds the right job. In this case, even though this person is still looking for a better job and would be more productive as a kindergarten teacher, she would still be counted as employed. This means that the unemployment rate would understate the true employment situation.

Another concern is the discouraged worker effect. Consider an economy that is experiencing a severe recession; it currently has a labor force of 200, and 50 of those people are unemployed (yielding an unemployment rate of 25 percent). If these unemployed people have searched for at least a year and still cannot find jobs, they may give up looking for a job and exit the labor force. Suppose half of the unemployed people leave the labor force. Now, there are only 25 people who are unemployed, and there are 175 people in the labor force, yielding an unemployment rate of 14.9 percent. Note that the unemployment situation did not improve, but the unemployment rate did!

According to our analysis of markets in Chapter 6, unemployment really shouldn’t happen. Recall that if markets operate effectively, the market will adjust until the quantity supplied equals the quantity demanded and markets clear at the equilibrium price. However, persistent unemployment means that the quantity of labor supplied exceeds the quantity demanded at the current market wage. That leads us to the unhappy conclusion that the labor market does not operate effectively.

As in other markets, we can usually trace this market failure to some problem in price adjustment, meaning that the wage rate does not adjust appropriately. There are many reasons that this may occur, but the following three are pretty easily recognizable and are generally accepted by economists as some of the reasons that wages don’t adjust. First, the existence of minimum wage laws keeps wages from adjusting downward if they are binding (see Chapter 6). Second, when labor unions, or any group of employees, are able to negotiate wages above the equilibrium wage, this can generate unemployment.

A third and more interesting example is something known as efficiency wage theory. According to this theory, wages are higher than the market-clearing wage not because some outside force makes this happen, but because firms voluntarily pay higher than equilibrium wages. This seems strange—why would a firm pay more for a worker than it has to? Consider this: if there is no unemployment, then finding a job if you get fired is pretty easy. After all, if there is no surplus of workers, a person should have an easy time finding a new employer to give him a job. Given this, employees may have little incentive to work to full capacity, as the fear of unemployment is gone. However, if firms pay higher wages, this decreases the quantity of workers they are willing to hire and increases the quantity of workers who are willing to supply their labor at the higher wage, creating a pool of unemployed people. Now, if workers lose their jobs, they are losing a higher-paying job and get thrown into a pool of the unemployed.

Measures of the state of a nation’s macroeconomic labor market are important indicators of the strength of the economy. Adults are classified as either employed, unemployed, or not in the labor force. The sum of the employed and the unemployed is known as the labor force. An important distinction between a person who is unemployed and a person who is out of the labor force is that a person must have actively sought a job to be counted as unemployed. The unemployment rate is simply the number of unemployed persons as a percentage of the entire labor force. If the economy is producing at its potential level of output, the labor markets are said to be at their natural rate of unemployment. Economists see unemployment as a situation in which labor markets are not clearing because the wage cannot adjust downward to the point where the supply of labor intersects the demand for labor. This may be due to minimum wage laws, workers who are under contract for a fixed wage, or the theory of efficiency wages.

Recall that one of the concerns we have is that unemployment might actually be too low. One of the reasons we are concerned about very low levels of unemployment is that in a tight job market, firms may raise wages in order to attract workers. This sounds great from a worker’s point of view, but if firms have to pay more for workers, they will pass this along to the purchasers of goods and services, and prices will start to rise. This is one of the ways in which a general rise in the price level, a phenomenon known as inflation, might occur; we talk about this in the next chapter.

For each of the following, choose the answer that best fits.

1. As a percentage of the total labor force, the unemployment rate measures:

A. The number of people in an economy who do not have jobs.

B. The number of people in an economy who have jobs.

C. The number of people who are out of work and actively looking for work.

D. The number of people who are looking for work.

2. According to the efficiency wage theory, which of the following leads to unemployment?

A. Firms are paying a wage that is higher than the market would otherwise generate.

B. Firms are paying wages below the market equilibrium wage to cut costs and earn monopoly profits.

C. Workers are willing to work for less than the minimum wage.

D. All of the above.

3. Which one of the following types of people is not counted as part of the labor force?

A. People who are too young to work.

B. People who are in the military.

C. People who are institutionalized.

D. None of the above are counted as part of the labor force.

4. Suppose there is a severe recession and unemployed people stop looking for work. All else equal, which of the following would occur?

I. The labor force participation rate would decrease.

II. The unemployment rate would decrease.

III. The unemployment rate would increase.

A. I only

B. II only

C. III only

D. I and II

5. Which of the following types of unemployment may actually be both unavoidable and desirable?

A. Structural unemployment

B. Frictional unemployment

C. Seasonal unemployment

D. Cyclical unemployment

Use the following scenario to answer questions 6 through 10.

The BLS conducted a survey of all the residents of Smallville. Of the 21 residents, 9 were age 15 and under. The following describes the rest of the residents:

Maggie, age 17, full-time student, not working, not looking for work.

Grace, age 35, works 10 hours per week but is looking for another part-time job.

Owen, age 40, works 45 hours per week.

Erin, age 29, works 40 hours per week.

Bridgette, age 25, works 35 hours per week.

Luke, age 65, works 20 hours per week.

Andrew, age 50, works 30 hours per week.

Jude, age 21, does not work but is looking for a job.

Alex, age 30, does not work but is looking for a job.

Max, age 16, full-time student, not working, not looking for a job.

Ella, age 26, works 40 hours per week as an officer in the U.S. Marine Corps office in Smallville.

Jack, age 52, does not work and gave up looking for work last month.

6. Complete Table 12-2.

TABLE 12-2 Residents of Smallville

7. What is the civilian, noninstitutionalized population? What is the labor force?

8. What is the labor force participation rate?

9. What is the unemployment rate?

10. How might this unemployment rate distort the true employment situation? (Hint: Use Jack in your explanation.)