Gödöllő Palace • Lázár Lovaspark • Hollókő • Szentendre • Visegrád • Esztergom • More Hungarian Destinations

Budapest Day Trips at a Glance

Sights in Hollókő’s Old Village

South of Budapest: The Great Hungarian Plain

West of Budapest: Lake Balaton and Nearby

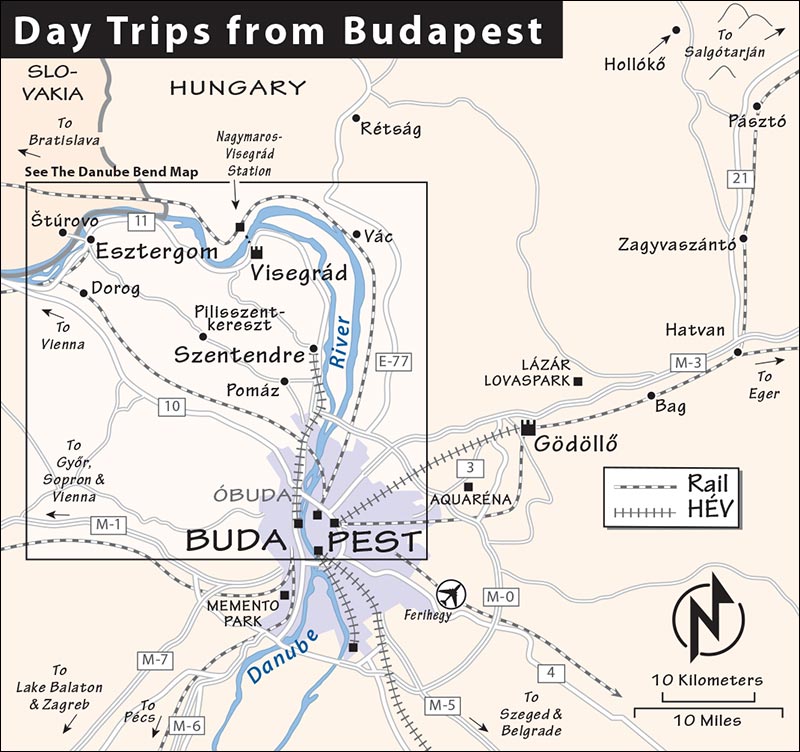

The most rewarding destinations outside Budapest are Eger, Pécs, Sopron, and Bratislava (Slovakia). But each of those (covered in their own chapters) is more than two hours away; for a shorter visit, the region immediately surrounding Budapest offers some enticing options for a break from the big city.

I’ve arranged these in geographical clusters, east and west of the capital. To the east, just outside Budapest, Gödöllő Palace is the best spot in Hungary to commune with its past Habsburg monarchs, the larger-than-life Franz Josef and Sisi. Nearby, Lázár Lovaspark is the handiest opportunity to take in a traditional Hungarian cowboy show. The tiny village of Hollókő, tucked in the hills northeast of Budapest, combines a living community with an open-air folk museum.

Meanwhile, west of Budapest, three river towns along the Danube Bend offer an easy escape: the charming town of Szentendre is an art colony with a colorful history to match; the castles of Visegrád boast a sweeping history and equally grand views over the Bend; and Esztergom is home to Hungary’s top church.

At the end of this chapter, I’ve briefly outlined two areas that—while a bit too far for a day trip—are worth knowing about for those who want to extend their Hungarian explorations: the Great Hungarian Plain (including the city of Szeged) and Lake Balaton.

Of this chapter’s main attractions, Gödöllő Palace and Szentendre are the easiest to reach from Budapest (each one is a quick ride away on the suburban train, or HÉV). These sights—which are also the best attractions in this chapter—can be done in just a few hours each. Lázár Lovaspark is an easy taxi ride from Gödöllő. The other sights (Hollókő, Visegrád, and Esztergom) are farther afield and less rewarding; do these only if you have extra time or they’re on the way to your next stop.

For efficient sightseeing, cluster your visits to these sights strategically. If you have a car, some combination of Gödöllő Palace, Lázár Lovaspark, and Hollókő can be done in a day (round-trip from Budapest, or on a long day driving between Budapest and Eger; for details, see here). The Danube Bend sights (Szentendre, Visegrád, and Esztergom) also go well together if you have a car, and line up conveniently between Budapest and Bratislava or Vienna.

These three attractions—Gödöllő Palace, Lázár Lovaspark horse show, and the folk village of Hollókő—line up east of Budapest. Each one is a detour from the M-3 expressway that heads northeast; consider stopping at one or more of these on your way to Eger, or seeing two or three as a side-trip from Budapest. Gödöllő Palace is also easy to reach by train from Budapest.

Holding court in an unassuming town on the outskirts of Budapest, Gödöllő Royal Palace (Gödöllői Királyi Kastély; pronounced roughly “GER-der-ler”) is Hungary’s largest Baroque palace and most interesting royal interior to tour. The pink-and-white, U-shaped Baroque complex is haunted by Habsburg ghosts: Once the residence of Habsburg Emperor Franz Josef and his wife, Empress Elisabeth (known as Sisi), Gödöllő has recently been restored to its “K und K” (royal and imperial) splendor. Compared to other Habsburg properties, Gödöllő is compact, well-presented, and pleasantly uncrowded. If you want a Habsburg fix and aren’t going to Vienna—or if you’re a Habsburg completist—Gödöllő is worth ▲▲, and well worth a half-day visit from Budapest.

Cost and Hours: Permanent exhibit (main palace apartments)-2,200 Ft; April-Oct daily 10:00-18:00, last entry one hour before closing; Nov-March open only by guided tour at :30 past each hour Mon-Fri 10:30-14:30 (palace closes at 16:00), Sat-Sun 10:00-17:00; tel. 28/410-124, www.kiralyikastely.hu. For the cost and hours of the other palace attractions, see later.

Getting There: Gödöllő Palace is an easy side-trip from Budapest, by HÉV suburban train or by car. By public transit, take the M2/red Metró line to the end of the line at Örs vezér tere, then go under the street to the HÉV suburban train (H8/pink line) and hop a train marked for Gödöllő (2/hour). Once in Gödöllő, get off at the Szabadság tér station (about an hour total from central Budapest). The palace is across the street, kitty-corner from the station. Drivers will find the palace 17 miles east of Budapest, just off the M-3 expressway (on the way to Eger and other points east). You’ll find pay-and-display parking directly in front of the palace.

Audioguide: You can rent an 800-Ft audioguide for the permanent exhibit, but this chapter’s self-guided tour covers the basics, and enough English descriptions are posted throughout to bring meaning to each of the rooms and exhibits.

Services: The palace houses a café that Sisi would appreciate. There’s also baggage storage (no bags are allowed within the tourable parts of the palace).

Time to Allow: By public transportation, figure an hour each way from central Budapest, plus another hour or so to tour the palace. You’ll need additional time to visit the other sights at the palace (such as the Baroque theater or WWII-era bunker).

Starring: That quintessential royal and imperial couple, Franz Josef and Sisi.

The palace was built in the 1740s by Count Antal Grassalkovich, a Hungarian aristocrat who was loyal to Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa (at a time when most Hungarians were chafing under her rule). When the Compromise of 1867 made Habsburg rulers Franz Josef and Sisi “king and queen of Hungary” (see here), the couple needed a summer home where they could relax in their Hungarian realm—and Gödöllő Palace was that place. Sisi adored Hungary (in many ways preferring it to Vienna) and spent much of her time here; Franz Josef especially enjoyed hunting in the surrounding woods. The family spent many Christmases at Gödöllő. More than 900 servants worked hard to make this a pleasant second home for just that one family.

After the fall of the monarchy, Gödöllő Palace became a residence of Admiral Miklós Horthy, who led Hungary between the World Wars. The palace fell into disrepair during the communist period (when the Soviets gutted it of period furniture and used it as military barracks, and then a nursing home). But it was recently rehabilitated to Habsburg specifications and opened to the public. Two wings of the palace are still in ruins, and renovations are ongoing.

The most interesting part of the palace is its permanent exhibit, which fills several wings: the Grassalkovich wing, Franz Josef wing, Sisi wing, and Gisella wing, which you’ll visit in that order. Pleasant gardens stretch behind the palace. Various other parts of the palace—such as a Baroque theater, the stables, and Admiral Horthy’s bunker—are also tourable, but not really geared for English-speakers. See the details for these after the self-guided tour.

• After buying your ticket, head upstairs and go left, following the marked tourist route. To help you find your way, the numbers noted below correspond to the audioguide numbers you’ll see posted in each room.

You’ll begin in the small dining room (#4)—where the table is set with exquisite Herend porcelain made specifically for this palace—then see the butler’s pantry (#5), displaying more porcelain. The actual kitchens were in another building, across the park, because Sisi didn’t care for the smell of cooking food.

Head down the long hallway, bypassing the small side-rooms for now; at the end of the hall, do a quick clockwise loop through the adjoining Grassalkovich wing, named for the aristocratic family that built the original palace. (When this family died out in 1841, the palace went to the Habsburgs.) If this obscure blue blood doesn’t thrill you, take the opportunity to simply appreciate the opulent apartments. From Room #7 (displaying a countess’ robin’s-egg-blue gown), you’ll hook to the right, through a small armory collection, to reach the oratory (#10/#11), which gives you a peek down into the chapel. This room allowed the royal couple to “attend” Mass without actually mingling with the rabble. Notice the chapel’s perfect Baroque symmetry: two matching pulpits, two matching chandeliers, and so on. Continue your loop, watching on the right for the hidden indoor toilet, and then—built into the door frame—the secret entrance to passages where servants actually scurried around inside the walls like mice, serving their masters unseen and unheard. (Notice that the stoves have no doors—they were fed from behind, inside the walls.)

Circling the rest of the way around to the blue gown, turn left, then head back down the long hallway. Turn left near the end of the hall into the Franz Josef wing, starting in the Adjunct General’s Quarters (#15). In the next room, the coronation chamber (#16), we finally catch up with the Habsburgs. Look for the giant painting of Franz Josef being crowned king of Hungary at Matthias Church, on top of Buda’s Castle Hill, in 1867. (On the right side, hat in hand, is Count Andrássy. He gestures with the air of a circus ringmaster—which makes sense, as he was a kind of MC of both this coronation and the Hungarian government in general. Andrássy is the namesake of Pest’s main drag—and was the reputed lover of Franz Josef’s wife Sisi.) Across the room is a painting of another Franz Josef coronation, this time at today’s March 15 Square in Pest. Back then, Buda and Pest were separate cities—so two coronations were required.

In the study of Franz Josef (#17), on the right wall, we see a portrait of the emperor, with his trademark bushy ’stache and ’burns. The painting of the small boy (to the left) depicts Franz Josef’s great-great-nephew Otto von Habsburg, the Man Who Would Be Emperor, if the empire still existed. Otto (1912-2011) was an early proponent of the creation of the European Union. (The EU’s vision for a benevolent, multiethnic state bears striking similarities to the Habsburg Empire of Franz Josef’s time.) Otto celebrated his 90th birthday (in 2002) here at Gödöllő Palace. The bust is Otto’s father—Austrian Emperor Charles I, aka Hungarian King Károly IV. He was the last Habsburg emperor, ruling from the death of Franz Josef in 1916 to the end of World War I (and the end of that great dynasty) in 1918. Sisi looks on from across the room.

The reception room of Franz Josef (#18) displays a map of the Habsburg Empire at its peak, flanked by etchings featuring 12 of the many different nationalities it ruled. The big painting on the right wall shows the Hungarian Millennium celebrations of 1896 at the Royal Palace at Buda Castle. Also in this room, near the smoking area, notice the very colorful reconstructed stove.

The lavishly chandeliered grand ballroom (#19) still hosts concerts. Above the main door, notice the screened-in loft where musicians could play—heard, but not seen. This placement freed up floor space for dancing in this smaller-than-average ballroom.

• At the far end of the grand ballroom, you enter the...

This wing—where the red color scheme gives way to violet—is dedicated to the enigmatic figure that most people call “Empress Elisabeth,” but whom Hungarians call “our Queen Elisabeth.” Sisi adored her Hungarian subjects, and the feeling was mutual. At certain times in her life, Sisi spent more time here at Gödöllő Palace than in Vienna. While the Sisi fixation is hardly unusual at Habsburg sights, notice that the exhibits here are particularly doting...and always drive home Sisi’s Hungarian affinities.

In the reception room (#20), along with the first of many Sisi portraits, you’ll see the portrait of Count Gyula Andrássy. Sisi’s enthusiasm for all things Hungarian reportedly extended to this dashing aristocrat, who enjoyed riding horses with Sisi...and allegedly sired her third daughter, Marie Valerie—nicknamed the “Little Hungarian Princess.”

In Sisi’s study (#21), see the engagement portraits of the fresh-faced Franz Josef (age 23) and Sisi (age 16). Although they supposedly married for love, Sisi is said to have later regretted joining the imperial family. The book by beloved Hungarian poet Sándor Petőfi, from Sisi’s bedside, is a reminder that Sisi could read and enjoy the difficult Magyar tongue. (It’s also a reminder of Sisi’s courageous empathy for the Hungarian cause, as Petőfi was killed—effectively by Sisi’s husband—in the Revolution of 1848.)

You’ll then pass through Sisi’s dressing room (#23, with small family portraits) and bedroom (#24, with faux marble decor). Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa spent two nights here in 1751, a century before it became Sisi’s bedroom. Next up are three more rooms with exhibits on Sisi. In the second room, look for the letter in Hungarian, written in Sisi’s own hand (marked as item #17 in the display case) and an invitation to her wedding (set with the fancy lace collar). The third room, with a bust of Sisi, is filled with images of edifices throughout Hungary that are dedicated to this beloved Hungarian queen (such as Budapest’s Elisabeth Bridge).

• Now proceed into the...

Explore these six rooms, which are filled with an exhibit that brings the palace’s history up to the 21st century. In the first room, you’ll see a huge painting of Sisi mourning Ferenc Deák, the statesman who made great diplomatic strides advocating for Hungarian interests within the Habsburg realm. There’s also a more-intimate-than-usual portrait of Franz Josef, with the faint echoes of a real personality (for a change).

Also in this wing are interactive children’s exhibits. The blue room introduces you to Sisi’s children, including Gisella (the wing’s namesake), Rudolf (whose suicide caused his cousin Franz Ferdinand to become the Habsburg heir apparent), and Maria Valeria (the so-called “Little Hungarian Princess”).

Finishing your tour, you’ll learn how, in the post-Habsburg era, this building became a summer home for Admiral Miklós Horthy, and later a military base and nursing home, with photographs showing the buildings during each of those periods. The final room displays impressive before-and-after photos illustrating how this derelict complex was only recently restored to its past (and current) glory. You’ll exit into a gallery with (surprise, surprise) even more Habsburg portraits.

• The permanent collection is enough for most visitors. But there are also several intriguing...

These extra activities add different dimensions to your experience here. Unfortunately, they’re primarily geared toward Hungarian visitors—most require joining a guided tour, which rarely run in English. You can call to ask if an English tour is scheduled; also, some palace guides speak English, and may be willing to tell you a few details after their Hungarian spiel.

This reconstructed, fully functional, 120-seat theater can be visited only with a 30-minute guided tour. You’ll go backstage to get a good look at the hand-painted scenery, and below the stage to see the pulleys that move that scenery on and offstage. While it’s fascinating to theater buffs, the facility feels new rather than old (it’s computer-operated), diminishing the “Baroque” historical charm.

Cost and Hours: 1,400 Ft, or 1,100 Ft with palace ticket, English tour may be possible 1-2/day on weekends but unlikely on weekdays, otherwise join Hungarian tour and use English handout.

One ticket covers a 40-minute tour of these three sights. The equestrian sights may interest horse lovers, and the movie is interesting to anyone.

The beautifully restored stables lead to the high-ceilinged, chandeliered riding hall that can still seat 400 people for special events. Upstairs is a small, good museum (in English) on Hungary’s proud equestrian tradition, with high-tech displays and lots of old uniforms, saddles, and other equipment.

The 10-minute 3-D movie does a good job of illustrating the history of the royal palace, including virtual re-creations of past versions of the building and its gardens, and dramatic re-enactments of Franz Josef and Sisi’s favorite pastimes here. While normally shown in Hungarian, you can try requesting a showing of the English version.

Cost and Hours: 1,200 Ft, or 900 Ft with palace ticket, tours at :30 past each hour Thu-Sun 10:30-16:30, no tours Mon-Wed, generally in Hungarian with English handout.

Gödöllő was a summer residence of Miklós Horthy, the sea admiral who ruled this landlocked country between the World Wars (during Hungary’s “kingdom without a king” period). Near the end of his reign, soon before the Nazis invaded, Horthy had a stout bunker built underneath the palace. On the 30-minute required tour, you’ll see the two oddly charming, wood-paneled rooms where Horthy and his family would have holed up in case of invasion. (The hominess was designed to make the space more tolerable for Horthy’s deeply claustrophobic wife.) The bunker wasn’t even finished until after the Nazis took over, and the communist government stored gasoline here for decades—you can still smell the fumes.

Cost and Hours: 800 Ft, or 700 Ft with palace ticket, tours daily year-round at 10:30 and 14:00, generally in Hungarian with an English handout.

On summer Sunday afternoons, the palace hosts a one-hour presentation of its trained birds and talented archers. As with most activities here, it’s in Hungarian only—but still plenty entertaining.

Cost and Hours: 1,500 Ft, May-Sept Sun only at 15:00.

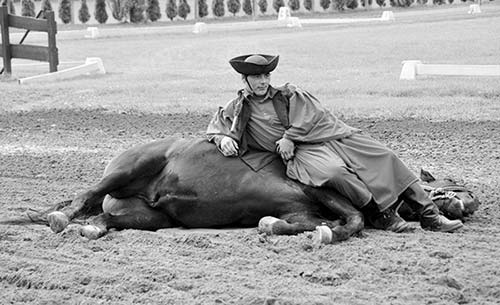

Hungary has a rich equestrian tradition dating back to the time when those first Magyars rode across the Asian steppes to Central Europe. And, like the American West, Hungary’s rugged Great Plain was settled by brave cowboys (here called csikós). As in the US, a world of vivid folklore surrounds these rough-and-tumble cattle wranglers, who are romantically thought of as camping out under the stars and slow-simmering a rich paprika broth in a copper kettle over an open fire (the origin of gulyás leves, “shepherd’s soup”—a.k.a. goulash). Today, several places around Hungary offer the chance to see a working farm with Hungary’s many unique livestock, and take in a thrilling presentation that telescopes a millennium of show-off equestrian talent into one big extravaganza. While authentic, these traditions are kept alive today mostly for curious tourists—so Hungarian horse shows can feel a little hokey. But if you surrender yourself to the remarkable horsemanship, and the connection riders have with their magnificent animals, it’s a hoot.

Most horse shows are performed in places where real-life Hungarian cowboys roamed: on the Great Hungarian Plain at Hortobágy National Park (for details, see here). But seeing one of those requires an all-day side-trip from Budapest. A handy alternative, the family-run Lázár Lovaspark, worth ▲, is in Budapest’s northeastern suburbs—27 miles from the capital, and just nine miles from Gödöllő, making it easy to combine with the royal palace or Hollókő folk village for a busy but fun day out.

It’s workable by public transportation, but taxis are helpful to connect the dots. From the train station in Gödöllő (connected by frequent trains to downtown Budapest—see here), you can take a taxi to Lázár Lovaspark (figure about 2,000 Ft one-way, 15 minutes). You can also reach Lázár Lovaspark directly by public bus from Budapest (runs sporadically Mon-Fri, less Sat-Sun): From the Stadionok bus station (on the M2/red Metró line), ride the bus about 50 minutes, get off at the Domonyvölgy stop (with a small wooden bus shelter), and walk about a half-mile to the park (from the bus stop, cross the street to the other bus stop, and walk down the road—Fenyő utca).

Drivers can exit the M-3 expressway east of Budapest for Gödöllő, then follow signs for Domonyvölgy. Consider hiring a driver for a day trip to both Gödöllő and Lázár Lovaspark, or stop off on the drive from Budapest to Eger.

Lázár Lovaspark, in the village of Domonyvölgy, is a working farm that’s picturesquely set at the base of gently rolling hill. The Lázár brothers have won 16 world championships in carriage riding, and lovas is a term meaning, roughly, “equestrian arts.”

Cost: 4,000 Ft, includes welcome snack and schnapps, horse show, brief tour, and carriage ride—about 1.5 hours in total.

Hours: Shows generally take place April-Sept daily at 11:30 or 12:00, and at 15:00 and 17:00. But the schedule can vary, so it’s essential to call ahead to confirm the time before planning your day around it (and to let them know you’re coming). Off-season, shows are often held for private groups (others are welcome to join), but the schedule is less predictable—call ahead.

Information: It’s at Fenyő utca 47 in Domonyvölgy, tel. 28/576-510, mobile 0630-871-3424, www.lazarteam.hu, lazarteam@lazarteam.hu.

Your visit to the park has several parts.

Museum, Stables, and Barnyard Tour: A 20-minute tour takes you to a small “hall of champions” museum celebrating the Lázár clan’s illustrious history, and the stables where the horses live (each stall marked with its occupant’s prestigious bloodlines). Then you’ll visit the barnyard—strangely fascinating for the chance to meet several only-in-Hungary animals: the woolly pig, mangalica; the giant gray longhorn cattle, szürkemarha; and the corkscrew-antlered goat, racka. The farm even has a puli sheepdog, with its dreadlock-like coat.

Horse Show: The main event is a 40-minute presentation neatly designed to show off various aspects of Hungary’s long equestrian tradition. While there may be commentary during the show, it might not be in English—here’s what to watch for: First come the Magyar-style archers, who ride fast as they shoot arrows and throw spears with deadly accuracy at a target (at first stationary, and then moving). Then Hungarian cowboys, clad in blue uniforms, crack their whips as they ride in. They’ll show how the whips could be used to disarm an enemy, as well as to train horses not to be startled by gunshots. To demonstrate how well-trained the horses are, the cowboys get their horses to kneel, then lie down—all while the rider is still seated. They explain that nights spent out on the Great Hungarian Plain were far more comfortable when the cowboy could lie on top of his reclining horse. And the cowboys stage a competition to see who can spill the least amount of suds from a full mug of beer while galloping around the track. For comic relief, a rodeo-clown-type “shepherd boy” attempts to get his donkey to do some of the tricks he’s seen the horses tackle. Then a carriage rumbles in, pulled by the gigantic grey longhorn cattle called szürkemarha—which, it’s believed, accompanied those original Magyars on their initial trip here from Asia. A costumed “Sisi” rides out sidesaddle on a clever Lipizzaner stallion, who elegantly do-si-dos a brief routine. Then comes the stirring climax of the show: the famous “Puszta five,” where a horseman stands with one foot on each of two horses, while leading three additional horses with reins—galloping at breakneck speed around the track as if waterskiing. Finally the entire gang takes a victory lap.

Carriage Ride: After the show, you’ll have the option to hop on an open carriage for a bumpy but fun 15-minute ride through the surrounding plain and forest.

Worth ▲, remote, minuscule Hollókő (HOH-loh-ker), nestled in the hills a 1.5-hour drive from Budapest, survives as a time capsule of Hungarian tradition. This proud village is half living hamlet, half open-air folk museum; unlike many such places around Europe, people actually reside in quite a few of Hollókő’s old buildings. To retain its “real village” status, Hollókő has its own mayor, elementary school, general store, post office, and doctor (who visits twice a week). The village is a treasured part of Hungarian cultural history; an extensive renovation project—which may open some new sights beyond those mentioned here—is due to wrap up in mid-2015.

Hollókő is worth a visit for those who are interested in Hungarian folk culture, especially if you have a car. Note that most of the village shuts down off-season (Oct-Easter) and on Mondays; at these times, skip Hollókő.

Hollókő is in a distant valley about 60 miles northeast of Budapest. By car, it’s about a 1.5-hour drive (assuming light traffic): Take the M-3 expressway east, exit at Hatvan (exit 55), and follow road #21 north toward Salgótarján. Keep an eye out (on the left) for the turnoff for Hollókő and Szécsény, then carefully track Hollókő signs. From Eger, figure about 1.5 hours (fastest via the M-3 expressway west, then follow the directions above).

In the summer, and on Sundays year-round, it’s possible (but more time-consuming) to reach Hollókő by public transit: A bus leaves from Budapest’s Stadionok bus station daily year-round at 15:15; on weekends only (Sat-Sun), a second bus departs at 8:30. Buses return to Budapest on a similar schedule (May-Aug daily at 14:00; year-round Sat-Sun at 16:00; plus one early-morning departure at 5:00 on weekdays). The trip takes about two hours each way. Notice that this schedule makes a same-day round-trip from Budapest impossible on weekdays.

Hollókő deserves at least a couple of hours; a half-day is about right for most visitors. With a car, consider detouring to Hollókő between Budapest and Eger. Remember, Gödöllő Palace and Lázár Lovaspark (which are also off the M-3 expressway) connect well with Hollókő; you could see some combination of these as a side-trip from Budapest, or on the way between Budapest and Eger.

The village is particularly worthwhile on festival days (listed at www.holloko.hu). Don’t bother on a Monday or off-season, when nearly everything is closed.

If choosing what to visit at Hollókő, the Village Museum is the most worthwhile, followed by the Doll Museum. The others sights are skippable, but it’s worth poking into several shops. Hike up to the castle only if you’ve got time and energy to burn.

Hollókő (total pop.: about 350) is a village squeezed into a dead-end valley overlooked by a castle. The hamlet is divided into two parts: the Old Village (with all the protected old houses, shops, and museums, and about 35 residents) and the New Village. The bus stop and big parking lot are just above the entry point to the Old Village. There’s an ATM and a WC behind the pub that overlooks the entrance to the Old Village.

Hollókő’s useful TI is at the entrance to the Old Village, at the Hollóköves Infocafé. They can give you a brochure and help you find a room (summer daily 8:00-18:00, sometimes until 20:00; winter Mon-Fri 8:30-16:00, Sat-Sun open only briefly or closed entirely; Kossuth utca 50, mobile 0620-626-2844, www.holloko.hu).

Local Guide: Since English-speakers get little respect at Hollókő (only a few borrowable translations in some museums), you owe it to yourself to hire a local guide. Ádám Kiss is a young city slicker who fell in love with Hollókő and moved here with his wife and kids to become part of the community. Ádám, who lived in Montana and speaks good English, will enthusiastically make your time here more meaningful, and he’s a great value. He also works as a driver/guide in nearby destinations, including Gödöllő Palace and Eger (6,500 Ft/2-hour tour, does not include entrance fees, more for multi-day driving tours, mobile 0620-379-6132, adamtheguide@gmail.com).

The Old Village at Hollókő is a perfectly preserved enclave of the folk architecture, dress, and traditions of the local Palóc culture. Because it’s in a dead-end valley, Hollókő’s folk traditions survived here well into the 20th century. (Only when villagers began commuting to other towns for work in the 1950s did they realize how “backward” they seemed to other Hungarians.)

Cost and Hours: It’s free to enter the Old Village, but each sight inside has its own modest entry fee (generally around 250 Ft). Unless otherwise noted, sights here are open Easter-Sept Tue-Sun 10:00-17:00, closed Mon; off-season, most places close entirely or are only open Sat-Sun in good weather. Assume that no English is spoken, but at most places you can ask to borrow English translations.

• I’ve listed these sights roughly in the order of an easy self-guided orientation walk. Start at the entry point into the Old Village, which begins where the cobbles do. Get oriented with the big wooden map posted nearby (which stands directly in front of the Hollóköves Infocafé—housing the TI). Across the paved street is the...

A local agency coordinates special events here for visiting groups. If you see the ladies in their colorful folk dresses (generally a few times each day in summer), feel free to gawk from over the fence. Hollókő’s men, who tended to go elsewhere for work, abandoned their old-fashioned outfits earlier; but the women, who remained in the valley, kept wearing traditional dress much longer. Their costume is marked by a big, round abdomen (a sign of fertility, created by layering many petticoats), an embroidered vest, and a colorful headdress. In this courtyard, you can pay 300 Ft to enter the weaving room and see an old loom.

• Now head down the village’s main street. As you walk, take a closer look at the...

The exteriors of these houses cannot be changed without permission, but interiors are modern (with plumbing, electricity, Internet access, phones, and so on). They once had thatched roofs with no chimneys (to evade a chimney tax), but a devastating fire in 1909 compelled residents to replace the thatch with tiles and add little chimneys. The thick walls are made of a whitewashed, adobe-type mix of mud and dung (which keeps things cool in summer and warm in winter). Thick walls, small doors (watch your head), small windows...small people back then. The big, overhanging roof (nicknamed the house’s “skirt”) prevents rain from damaging this fragile composition. Most began as one simple house along the road; as children grew and needed homes of their own, a little family compound evolved around a central courtyard.

• Continuing down through the village, pause at the fork in the road, in front of Hollókő’s...

A traveling priest says Mass here twice weekly. This is a popular wedding spot for Budapest urbanites charmed by its simplicity.

• Take the fork to the right (Petőfi út) and wander past a few more shops until the road rejoins. Continue a few yards down the street. On the left, you’ll see a vár/castle sign leading very steeply up to the town’s castle (which is prominent overhead; for a more gradual approach, read on). Across the street is the...

This little collection displays photos of Hollókő in the olden days—with thatched roofs and dirt roads...but otherwise looking much the same (250 Ft, closed Mon and Wed).

• Now backtrack and head back up on the other road (Kossuth út). On the right is the...

Step inside to see some 200 dolls dressed in traditional costumes of the area. Each is labeled with the specific place of origin and a basic English description, allowing you to see the subtle changes from village to village (250 Ft, daily 10:00-17:00).

• Farther up on the right is the...

The Old Village’s highlight, this is the only house here with an authentic interior (250 Ft, March-mid-Dec daily 10:00-18:00, closed off-season). Take a trip back a hundred years as you stroll through the house.

Visiting the Museum: You enter into the kitchen. Most of the family (including piles of kids) would sleep on the floor here, near the warmth of the stove. The doors on the back wall (behind the stove) lead to a smoker. This very efficient design allowed them to heat the house, cook, bake, and smoke foods all at the same time.

Then head into the main room (to the left as you enter). Even today, many older Hungarians have a “nice room” where they keep their most prized possessions and decorations. They let visitors peek in to see their treasures...then make them sit in the kitchen to socialize. In here you’ll see plates and clocks proudly displayed. Looking around this room also gives you clues to the family’s status. The pillows and linens piled on the bed (stored there during the day, as most family members bunked on the floor) indicate that this was a middle-class home. The linens were traditionally given by the bride’s father as a dowry to the groom, allowing the couple to start their life together. The matching furniture is delicately painted. The dresser is well-built and intricate, indicating that a carpenter was paid to make it (other furniture would have been more roughly built by the head of the household). The glass in the windows is not authentic; back then, they would have stretched pig bladders over the windows instead. Turn your attention to the ceiling: The rafters are painted blue to ward off flies (the blue hue contains copper sulfate, a natural insecticide). People would hang their boots (their most expensive item of clothing) up high to prevent mice from ruining them.

Now cross back over to the third room, used for storing tools and food. The matriarch of the house slept in here (on the uncomfortable-looking rope bed) and kept the key for this room, doling out the family’s ration of food—so in many ways, Grandma was the head of the household. When Granny wasn't watching, and while the rest of the family slept elsewhere in the house, a young woman of courting age could come here to meet up with a suitor, who’d sneak in through the window. (The Hungarians even have a verb for these premarital interactions—roughly, “storaging.”) Find the crude crib, used to bring a baby along with adults working the fields (notice it could be covered to protect from the sun’s rays). In other parts of Hungary, peasants were known to partially bury their babies in the ground to prevent them from moving around while they worked. (These days, we use TV—is that really so much more humane?) Look up to find the bread rack suspended from the ceiling—again, to rescue the bread from those troublesome mice. Out back, you’ll see the old wine press.

• Continue up the street. A bit farther up on the right, look for the...

This shows off old postal uniforms, equipment, stamps, and currency (500 Ft, April-Oct daily 10:00-18:00, closed off-season).

• A few more steps up, and you’ve completed your circle—you’re back at the town church. There’s one more sight in town. If you’re up for a 15-20-minute uphill hike, consider going up to the castle: First hike up to the big parking lot; from there, follow the rough path marked vár/castle (a bit uphill at first, then mostly level).

Hollókő’s castle originally dates from the 13th century. By the 16th century, it was on the frontier between Habsburg-held Hungary and the Ottoman invaders (who eventually conquered the castle and used it for their own defense for a century and a half). After the Habsburgs had retaken Hungary, Emperor Leopold I destroyed the castle prophylactically (in 1711, just after the failed War of Independence) to ensure his Hungarian subjects wouldn’t use it against him. It sat in ruins until 1966, when it underwent an extensive, 30-year-long renovation. There are only a few small exhibits to see inside, but it’s enjoyable enough to hike around to ever-higher and better panoramas (700 Ft, April-Oct daily 10:00-17:30, may be open in winter on good-weather Sat-Sun). Views over the Old Village give you a sense of how minuscule the town is. The nearby fields are used to graze Hollókő’s livestock, which stay out to pasture at all times rather than being stabled. The high hills on the horizon are across the border, in Slovakia.

The castle is also tied to the legend of how Hollókő (“Hill of the Ravens”) got its name: Supposedly the owner of a castle that stood on the hill above this one once kidnapped a girl from the village. The girl’s nanny, who was a witch, sent ravens to pick the castle apart, stone by stone.

This is a very sleepy place to spend the night, but those who really want to delve into village Hungary might enjoy it (and its accommodations are far cheaper than other cities or towns in this book).

The TI rents several rooms in nine traditional buildings right in the Old Village (figure Db-12,000 Ft including breakfast; see “Tourist Information,” earlier).

Tugári Vendégház, run by local guide Ádám Kiss and his wife, has four rooms in a nicely restored old building in the New Village, a five-minute walk from the main sights (8,500-10,500 Ft depending on room size, breakfast-1,200 Ft, Rákóczi út 13, tel. 32/379-156, mobile 0620-379-6132, www.holloko-tugarivendeghaz.hu, tugarivendeghaz@gmail.com).

Two restaurants near the entrance to Hollókő’s Old Village sling traditional, well-priced Hungarian food: Muskátli Restaurant and Vár Restaurant. Be warned that they both close early (by 18:00 or 19:00, just after the day-trippers go home), so don’t wait too long for dinner. At the start of the village, you’ll also see a pub. A humble grocery store is upstairs above the pub (Mon-Sat 7:30-15:30, closed Sun).

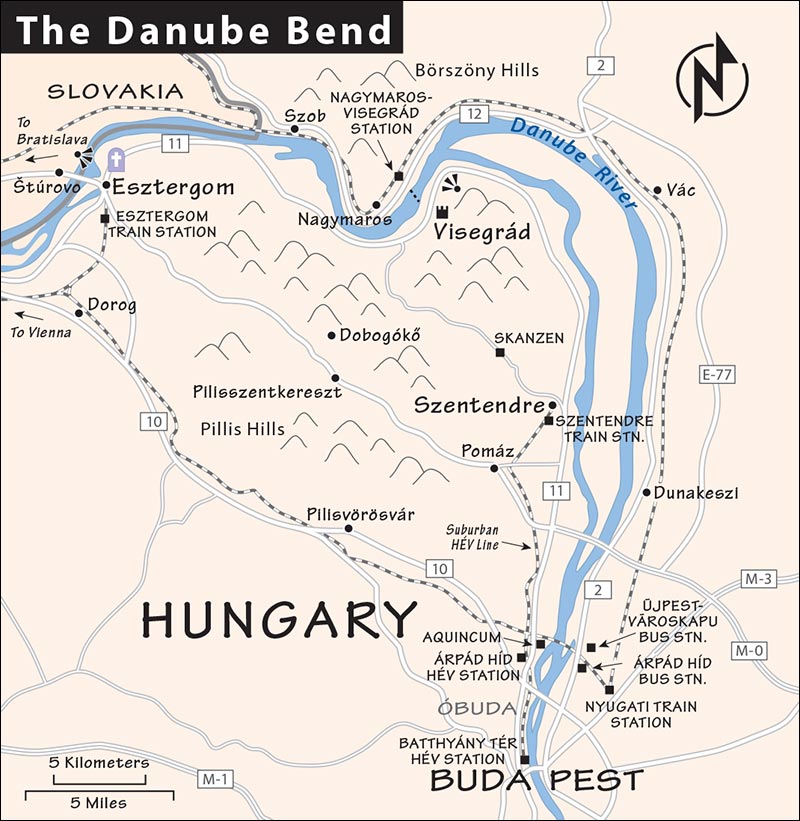

The Danube, which begins as a trickle in Germany’s Black Forest, becomes the Mississippi River of Central Europe—connecting 10 countries and four capitals (Vienna, Bratislava, Budapest, Belgrade) as it flows southeast through the Balkan Peninsula toward the Black Sea. Just south of Bratislava, the river squeezes between mountain ranges, which force it to loop back on itself—creating the scenic “Danube Bend” (Dunakanyar). Here Hungarians sunbathe and swim along the banks of the Danube, or hike in the rugged hills that rise up from the river. Hungarian history hides around every turn of the Bend: For centuries, Hungarian kings ruled not from Buda or Pest, but from Visegrád and Esztergom. And during the Ottoman occupation of Hungary, this area was a buffer zone between Christian and Muslim Europe.

Today, three river towns north of Budapest on the Danube Bend offer a convenient day-trip getaway for urbanites who want a small-town break. Closest to Budapest is Szentendre, whose colorful, storybook-cute Baroque center is packed with tourists. The ruins of a mighty castle high on a hill watch over the town of Visegrád. Esztergom, birthplace of Hungary’s first Christian king, has the country’s biggest and most important church. All of this is within a one-hour drive of the capital, and also reachable (up to a point) by public transportation.

Remember, Szentendre is the easiest Danube Bend destination—just a quick suburban-train (HÉV) ride away, it can be done in a few hours. Visegrád and Esztergom are more difficult to reach by public transportation; either one can require a substantial walk from the train or bus stop to the town’s major sight.

By public transportation, don’t try to see all three towns in one day; focus on one or two. (I’d skip Visegrád, whose castle is a headache to reach without a car.) To do the whole shebang, take a tour, rent a car, or hire a driver (see here) or local guide (here).

With a car, try this ambitious one-day plan:

| 9:00 | Leave Budapest. |

| 9:30 | Arrive at Szentendre and see the town. |

| 12:00 | Leave Szentendre. |

| 12:30 | Lunch in Visegrád. |

| 13:30 | Tour Visegrád Royal Palace and Citadel. |

| 15:30 | Leave Visegrád. |

| 16:00 | Visit Esztergom Basilica. |

| 17:00 | Head back to Budapest. |

With extra time, add a visit to the Hungarian Open-Air Folk Museum (“Skanzen”) near Szentendre.

If you’re driving between Budapest and Vienna (or Bratislava), the Danube Bend towns are a fine way to break up the journey, but seeing all three en route makes for a very long day—get an early start, or skip one.

Going north from Budapest, the three towns line up along the same road on the west side of the Danube—Szentendre, Visegrád, Esztergom—each spaced about 15 miles apart.

By Car: It couldn’t be easier. Get on road #11 going north out of Buda, which will take you through each of the three towns—the road bends with the Danube. As you approach Szentendre (at the traffic light, just before the train station—watch for Suzuki Szentendre and various hotel signs), branch off to the right, toward the old center and the river promenade. To return from Esztergom to Budapest, see “Route Tips for Drivers” at the end of this chapter.

By Boat: In the summer, Mahart runs boats from Budapest up the Danube Bend. The slower riverboats run to Szentendre (1.5 hours, May-Sept daily except Mon), Visegrád (3 hours, May-Aug daily except Mon, Sept Sat only), and Esztergom (5 hours, May-Aug daily except Mon, Sept Sat only); the faster hydrofoils (none to Szentendre, 1 hour to Visegrád, 1.5 hours to Esztergom) run only on summer weekends (May-Sept Sat-Sun). No boats run off-season (Oct-April). Check schedules and buy tickets at the Mahart office in Budapest (dock near Vigadó tér in Pest, tel. 1/484-4010, www.mahartpassnave.hu).

By Train: The three towns are on three separate train lines. Szentendre is truly handy by train, while Visegrád and Esztergom are less convenient.

Getting to Szentendre is a breeze by train—the HÉV, Budapest’s suburban rail, zips you right there (catch train on H5/purple line at Batthyány tér in Buda’s Víziváros neighborhood, easy connection via M2/red Metró line; 4-7/hour, 40 minutes each way, last train returns from Szentendre around 23:00).

The nearest train station to Visegrád is actually across the river in Nagymaros (this station is called “Nagymaros-Visegrád”; don’t get off at the station called simply “Nagymaros”). From the station, you’ll walk five minutes to the river and take a ferry across to Visegrád (see “Arrival in Visegrád” on here). Trains run hourly between Nagymaros-Visegrád and Nyugati/Western Station in Budapest (trip takes about 50 minutes).

To Esztergom, trains run hourly from Budapest’s Nyugati/Western Station (1.5 hours), but the Esztergom train station is a 45-minute walk from the basilica—I’d take a bus or boat instead.

By Bus: Without a car, buses are the best way to hop between the three towns. They’re as quick as the train if you’re coming from Budapest, but can be standing room only. There are two main routes. The river route runs hourly from Budapest along the Danube through Szentendre (30 minutes) and Visegrád (1.25 hours), then past Esztergom Basilica (2 hours, Iskola Utca stop) to the Esztergom bus station (more frequent during weekday rush hours). This bus leaves from Budapest’s Újpest-Városkapu bus station (at the M3/blue line Metró station of the same name). A different bus takes the overland shortcut (skipping Szentendre and Visegrád) to directly connect Budapest and Esztergom (1-2/hour, 1.25 hours, departs from Budapest’s Arpád híd station on the M3/blue Metró line). Buses make many stops en route, so you’ll need to pay attention for your stop (ask driver or other passengers for help).

By Tour from Budapest: If you want to see all three towns in one day but don’t have a car and don’t want to shell out for a private driver, a bus tour is the most convenient way to go. All of the companies are about the same (all 3 towns in about 10 hours, including lunch and shopping stops, plus return by boat, for around 20,000 Ft); look for fliers at the Budapest TI or in your hotel’s lobby.

Worth ▲, the Old Town of Szentendre (SEHN-tehn-dreh, “St. Andrew” in English) rises gently from the Danube, a postcard-pretty village with a twisty Mediterranean street plan filled with Habsburg Baroque houses. Arguably the most “Balkan-feeling” town of Hungary—thanks to the many diverse immigrants who settled the community—Szentendre promises a taste of Hungarian village life without having to stray far from Budapest...but it sometimes feels like too many other people have had the same idea. Szentendre is where Budapesters bring their significant others for that special weekend lunch. The town has a long tradition as an artists’ colony, and it still has more than its share of museums and galleries. It’s also packed with corny, gimmicky museums—a few of which (such as the Micro Art collection) are actually worthwhile. But the best plan is this: Venture off the souvenir-choked, tourist-clogged main streets...and you’ll soon have the quiet back lanes under colorful Baroque steeples all to yourself.

Little Szentendre (pop. 23,000) is easy to navigate. It clusters along a mild incline rising from the Danube, culminating at the main square (Fő tér) at the foot of Church Hill (Templomdomb). From the embankment—where most tourists arrive—various streets lead up to Fő tér, none more touristy than the souvenir gauntlet of Bogdányi utca.

The TI sits at the southern end of the old center, near the blocky modern tower of the Evangelical Church. Pick up the good town map, with sights and services well-marked (unpredictable hours but typically daily 10:00-17:30, Fri-Sun until 18:00, less off-season, Dumtsa Jenő utca 22, tel. 26/317-965, www.iranyszentendre.hu).

By Train or Bus: The combined train/HÉV and bus station is at the southern edge of town. To reach the town center from the station (about a 10-minute walk), go through the pedestrian underpass at the head of the train tracks. (A handy map of town is posted by the head of the tracks.) The underpass funnels you onto the small Kossuth Lajos utca. After a long block, you’ll pass the yellow Pozsarevacska Serbian Orthodox church, then cross the bridge; the TI is on the right, and the main square is three blocks straight ahead.

By Boat: Some boats arrive right near the main square, but most come to a pier about a 15-minute walk north of the center. After you get off the boat, take the first path to your left; stay on it, and it’ll lead you straight into town.

By Car: Approaching on road #11 from Budapest, turn right at the traffic light just after several signs directing you to hotels (also watch for the Suzuki Szentendre arrow). Park anywhere along the embankment road (pay and display); if you can’t find any free spaces, continue on to the large bus parking lot near the boat dock. From the embankment, it’s an easy uphill walk into town; all roads lead to the main square.

Margit Kovács Museum (Kovács Margit Múzeum)

Micro Art Museum (Mikro Csodák Múzueuma)

St. John Catholic Church (Keresztelő Szent János)

▲Belgrade Serbian Orthodox Cathedral (Belgrádi Székesegyház)

Hungarian Open-Air Folk Museum (Szabadtéri Néprajzi Múzeum, aka Skanzen)

Sightseeing in Szentendre is low-impact. While there are museums and churches to visit, the best plan for most is to simply stroll and people-watch through town and along the elevated Danube riverbank. Head off to the back streets, and you’ll be surprised at how quickly you’ll find yourself alone with Szentendre.

Szentendre’s top sight is the town itself. Start at the main square (Fő tér). Take a close look at the cross, erected in 1763 to give thanks for surviving the plague. Notice the Cyrillic lettering at the monument’s base. This is a reminder that in many ways, Szentendre is more of a Serbian town than a Hungarian one (see sidebar).

Face the cross and get oriented: Behind the cross, the square narrows as it curls around Church Hill, with its hilltop Catholic church; just behind that is the Orthodox Cathedral. Through a narrow alley to the left (between the red and yellow houses) is the fun Micro Art Museum. The street to the left (Dumtsa Jenő utca) leads to the Marzipan Museum and TI. To the right, the church fronting the square is Orthodox (called Blagovestenszka); it’s been closed for a lengthy restoration, but might reopen as a museum. And directly behind you (facing the cross) is the ticket office for Szentendre’s top art collection, the Margit Kovács Museum. All of these sights are described next.

The best of Szentendre’s small art museums celebrates the local artist Margit Kovács, highly regarded for her whimsical, primitive-looking, wide-eyed pottery sculptures. Kovács (1902-1977) was the first female Hungarian artist to be accepted as a major talent by critics and by her fellow artists. She came from a close-knit family, and had a religious upbringing, both themes that would appear frequently in her work. The down-to-earth Kovács, who never married, lived with her mother—her best friend and most constructive critic. This collection of her ceramic sculptures, displayed on several floors and explained in English, is organized by theme. You’ll see Christian, mythological, and folkloric subjects depicted side by side; even in many biblical scenes, the subjects wear traditional Hungarian clothing. Look for the room of sorrowful statues dating from after her mother’s death. On the top floor, in the replica of Kovács’ study, find the gnarled tree stump. This tree, which once stood on Budapest’s Margaret Island, had been struck by lightning, and its twisted forms inspired Kovács.

Cost and Hours: 1,000 Ft, daily 10:00-18:00, www.pmmi.hu. First buy your tickets at the office at the bottom of Fő tér (at #2-5). Then, you might be able to pass directly into the museum, or you might have to go around the block to get there (jog down Görög utca and take your first right to Vastagh György utca 1).

This charming and genuinely fascinating “Micro Miracles” collection, while a bit of a tourist trap, is worth a squint. Ukrainian artist Mikola “Howdedoodat” Szjadrisztij has crafted an array of 15 literally microscopic pieces of art—a detailed chessboard on the head of a pin, a pyramid panorama in the eye of a needle, a swallow’s nest in half a poppy seed, a golden lock on a single strand of hair, and even a minuscule portrait of Abe Lincoln. You’ll go from microscope to microscope, peering at these remarkably detailed sculptures.

Cost and Hours: 700 Ft, English descriptions, daily 9:00-18:00, down the appropriately tiny alley called Török föz at Fő tér 18-19, tel. 26/313-651.

This street, which leads away from Fő tér, is where you’ll find the...

This collection (attached to a popular candy and ice-cream store) features two floors of sculptures made of marzipan. Feast your eyes on Muppets, cartoon characters, Russian nesting dolls, an over-the-top wedding cake, a life-size Michael Jackson, and, of course, Hungarian patriotic symbols (the Parliament, the Turul bird, and so on). While fun for kids, this is skippable for adults. Note that there are similar marzipan museums in Eger and on Budapest’s Castle Hill; visiting more than one is redundant.

Cost and Hours: Free to enter shop, small fee for museum, daily 10:00-18:00, Dumtsa Jenő utca 12, enter from Batthyány utca, tel. 26/311-931, www.szamosmarcipan.hu.

For a representative look at Szentendre’s seven churches, visit the best two, connected by a loop walk.

• Begin on the main square (Fő tér). Go a few steps up the street at the top of the square (behind the cross). Just before the white Town Hall, climb the stairs on your right, and work your way up to the hilltop park, called...

This hill-capping perch offers some of the best views over the jumbled, Mediterranean-style roofline of old Szentendre. (See how many steeples you can count in this church-packed town.) Looking down on Fő tér, you can see how the town’s market square evolved at the place where its three trade roads converged.

• The hill’s centerpiece is...

This was the first house of worship in Szentendre, around which the Balkan settlers later built their own Orthodox churches. If it’s open, step into the humble interior (free, sporadic hours). Pay special attention to the apse, which was colorfully painted by starving artists in the early 20th century.

• Exiting the church, take the downhill lane toward the red-and-yellow steeple. Find the gate in the wall (along Alkotmány street) to enter the yard around this church. Pay a visit to the...

This offers perhaps Szentendre’s best opportunity to dip into an Orthodox church.

Cost and Hours: 600 Ft, also includes museum, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, shorter hours off-season; during winter, go to the museum first, then they’ll let you into the church.

Visiting the Church: Standing in the gorgeous church interior, ponder the Orthodox faith that dominates in most of the Balkan Peninsula (starting just south and east of the Hungarian border). Keep in mind that these churches carry on the earliest traditions of the Christian faith. Notice the lack of pews—worshippers stand through the service, with men separate from women, as a sign of respect before God. The Serbian Orthodox Church uses essentially the same Bible as Catholics, but it’s written in the Cyrillic alphabet (which you’ll see displayed around many Orthodox churches). Following Old Testament Judeo-Christian tradition, the Bible is kept on the altar behind the iconostasis—the big screen in the middle of the room covered with icons (golden paintings of saints), which separates the material world from the spiritual one.

Orthodox icons are typically not intended to be lifelike. Packed with intricate symbolism, and cast against a shimmering golden background, they’re meant to remind viewers of the metaphysical nature of Jesus and the saints rather than their physical form. However, this church, which blends pure Orthodoxy with Catholic traditions of Hungary, features some Baroque-style statues that are unusually fluid and lifelike.

Orthodox services generally involve chanting (a dialogue that goes back and forth between the priest and the congregation), and the church is filled with the evocative aroma of incense. The incense, chanting, icons, and standing up are all intended to heighten the experience of worship. While many Catholic and Protestant services tend to be more of a theoretical and rote consideration of religious issues, Orthodox services are about creating an actual religious experience.

Don’t miss the adjacent museum, covered by the same ticket. You’ll see religious objects, paintings, vestments, and—upstairs—icons, with good English descriptions.

• For a scenic back-streets stroll before returning to the tourist crush, go through the yard around the church, exit through the gate, turn left up the little alley, and then turn right at the T-junction, which takes you through what was the Dalmatian neighborhood to charming Rab-Ráby tér. The lanes between here and the waterfront are among the most appealing and least crowded in Szentendre.

Three miles northwest of Szentendre is an open-air museum featuring examples of traditional Hungarian architecture from all over the country. As with similar museums throughout Europe, these aren’t replicas—each building was taken apart at its original location, transported piece by piece, and reassembled here. The museum is huge and spread out, so a thorough visit could take several hours. The admission price includes a map in English, and the museum shop sells a good English guidebook for 1,000 Ft. Because it’s so large, the museum is worth visiting only if you can give it the time it deserves. Skip it unless you can arrange your visit to coincide with one of their frequent special-events-laden “festival days” (listed on their website).

Cost and Hours: 1,500 Ft, 100 Ft more on “festival days”; April-Oct Tue-Sun 9:00-17:00, closed Mon; mid-Feb-March Sat-Sun only 10:00-16:00, closed Mon-Fri; closed Nov-mid-Feb; last entry 30 minutes before closing, Sztaravodai út, tel. 26/502-500, www.skanzen.hu.

Getting There: It takes about five minutes to drive from Szentendre to Skanzen (pay parking). Bus #7 heads from Szentendre to Skanzen when the museum’s open (runs sporadically—see Skanzen website for specific schedule). A taxi from Szentendre to the museum should cost no more than 2,000 Ft; the TI can call one for you (mobile 0626-314-314).

Interchangeable, touristy restaurants abound in Szentendre. I enjoy the ambience at Promenade Vendéglő, with charming courtyard or indoor seating. They serve Hungarian and Balkan cuisine with take-your-time service (2,000-4,000-Ft main dishes, daily 10:00-22:00, Futó utca 4, along the Dunakorzó embankment, tel. 26/312-626).

Visegrád (VEE-sheh-grahd, Slavic for “High Castle,” pop. 1,600) is a small village next to the remains of two major-league castles: a hilltop citadel and a royal riverside palace. While the town itself disappoints many visitors, others enjoy the chance to be close to these two chapters of history.

The Romans were the first to fortify the steep hill overlooking the river. Later, Károly Róbert (Charles Robert), from the French/Neapolitan Anjou dynasty, became Hungary’s first non-Magyar king in 1323. He was so unpopular with the nobles in Buda that he had to set up court in Visegrád, where he built a new residential palace down closer to the Danube. (For more on this king, see here.) Later, King Mátyás (Matthias) Corvinus—notorious for his penchant for Renaissance excess—ruled from Buda but made Visegrád his summer home, and turned the riverside palace into what some called a “paradise on earth.” Matthias knew how to party; during his time here, red-marble fountains flowed with wine. (To commemorate these grand times, the town hosts a corny Renaissance restaurant, with period cookware, food, costumed waitstaff, and live lute music—you can’t miss it, by the palace and Hotel Vár.)

Today, both citadel and palace are but a shadow of their former splendor. The citadel was left to crumble after the Habsburg reoccupation of Hungary in 1686, while the palace was covered by a mudslide during the Ottoman occupation, and is still being excavated. The citadel is more interesting, but difficult to reach by public transport. Non-drivers may be better off skipping this town.

The town of Visegrád is basically a wide spot in the riverside road, squeezed between the hills and the riverbank. At Visegrád’s main intersection (coming from Szentendre/Budapest), the crossroads leads to the left through the heart of the village, then hairpins up the hills to the citadel. To the right is the dock for the ferry to Nagymaros (home to the closest train station, called Nagymaros-Visegrád—see “Arrival in Visegrád”).

The town has two sights. The less interesting, riverside Royal Palace is a 15-minute walk downriver (toward Szentendre/Budapest) from the village center. The hilltop citadel, high above the village, is the focal point of a larger recreational area best explored by car.

The town doesn’t have an official TI. You can get information at the giant Hotel Visegrád complex, which caters to passing tour groups at the village crossroads. They answer basic questions, sell maps, and hand out a few free leaflets. In summer, check in at the Visegrád Tours travel agency (May-Oct daily 8:00-17:30, generally closed Nov-April, Rév utca 15, tel. 26/398-160, www.visegrad.hu or www.visegradtours.hu); at other times, ask at the hotel reception desk (at the opposite end of the complex, through the unappealing Sirály restaurant).

Train travelers arrive across the river at the Nagymaros-Visegrád station (don’t get off at the station called simply “Nagymaros”). Walk five minutes to the river and catch the ferry to Visegrád, which lands near the village’s main crossroads (hourly, usually in sync with the train, last ferry around 20:30). Buses to Visegrád make several stops: the Királyi Palota stop is most convenient for the Royal Palace near the entrance to town, while the Nagymarosi Rév stop is at the main crossroads in the heart of town.

The remains of Visegrád’s hilltop citadel, while nothing too exciting, can be fun to explore. Only a few exhibits have English labels, but headsets allow you to hear information in English. Perhaps best of all, the upper levels of the citadel offer commanding views over the Danube Bend—which, of course, is exactly why they built it here.

Cost and Hours: 1,700 Ft, save 300 Ft if you skip the waxworks; daily May-Sept 10:00-18:00, March-April and Oct 9:00-17:00, may be open shorter hours Nov-Feb but always closes in icy winter weather, last entry 30 minutes before closing, tel. 26/398-101, www.parkerdo.hu/visegradi_var.

Getting There: To drive to the citadel, follow Fellegvár signs down the village’s main street and up into the hills (parking-300 Ft). Otherwise, you have two options: Get a map at Visegrád Tours/Hotel and hike 45 steep minutes up from the village center; or take the taxi service misleadingly called “City Bus.” This minivan trip costs 2,600 Ft one-way, no matter how many people ride along (ask at Visegrád Tours/Hotel, or call 26/397-372, www.city-bus.hu).

Visiting the Castle: Buy your ticket and hike up the path toward the castle entry. On the way up, you can pay extra to try your hand at a bow and arrow, or pose with a bird of prey perched on your arm.

Belly up to the viewpoint for sweeping Danube Bend views. From here, you can see that the Danube actually does a double-bend—a smaller one (upstream), then a bigger one (downstream)—creating an S-shaped path before settling into its southward groove. It’s easy to understand why the Danube, constricted between mountains, is forced to bend here. The river narrows as it passes through this gorge, then widens again below the castle, depositing sediment that becomes the islands just downstream. Just upstream from Visegrád, the strange half-lake on the riverbank is all that’s left of an aborted communist-era dam project to tame the river.

Climb up to the top of the complex. In the castle museum, you’ll see a replica of the Hungarian crown. The real one (now safely stored under the Parliament dome in Budapest) was actually kept here, off and on, for some 200 years, when this was Hungary’s main castle.

Deeper into the complex, you reach the waxworks (panoptikum), illustrating a scene from an important medieval banquet: In 1335, as Habsburg Austria was rising to the west, the kings of Hungary, Poland, and Bohemia converged here to strategize against this new threat. Centuries later, history repeated itself: In February of 1991, after the fall of the Iron Curtain, the heads of state of basically the same nations—Hungary, Poland, and Czechoslovakia—once again came together here, this time to compare notes about Westernization. To this day, Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia are still sometimes referred to collectively as the “Visegrád countries.”

Continue up to the very top of the complex, the inner castle. Here you’ll find a hunting exhibit (dioramas with piles of stuffed animals) and the armory (with a few weapons, and coats of arms of knights). To conquer the castle, climb up to the very top tower, where you can scramble along the ramparts.

Near the Citadel: Around the citadel is a recreational area that includes restaurants, a picnic area, a luge and toboggan run, a network of hiking paths, a Waldorf school, and a children’s nature-education center and campground.

Eating near the Citadel: Eating options in Visegrád are limited; most restaurants are big operations catering to tour groups. By the luge run (a lengthy-but-doable walk from the citadel), the Nagyvillám restaurant is elegant, with breathtaking views from the best tables (2,000-3,300-Ft main dishes, Mon-Thu 11:30-18:00, Fri-Sun 11:30-20:00, tel. 26/398-070). Only drivers can reach the picnic area (called Telgárthy-rét), in a shady valley with paths and waterfalls.

Under King Matthias Corvinus, this riverside ruin was one of Europe’s most elaborate Renaissance palaces. During the Ottoman occupation, it was deserted and eventually buried by a mudslide. For generations, the palace’s existence faded into legend, so its rediscovery in 1934 was a surprise. Today, the partially excavated remains are tourable, with sparse English descriptions.

Cost and Hours: 1,100 Ft, Tue-Sun 9:00-17:00, closed Mon, tel. 26/398-026, www.visegradmuzeum.hu.

Visiting the Palace: The palace courtyard, decorated with a red-marble fountain, evokes its Renaissance glory days. Upstairs, look for the giant green ceramic stoves, and at the top level, find the famous canopied fountain with lions. This “Hercules Fountain”—pictured on the back of the 1,000-Ft note—once had wine spouting from the lions’ mouths, with which Matthias used to ply visiting dignitaries to get the best results.

The small Solomon’s Tower up the hill from the Royal Palace (not worth the 700-Ft admission) once held a vampire...sort of. Vlad the Impaler, a nobleman who terrorized villagers in Transylvania (back when it was part of Hungary), was arrested and imprisoned here during the time of Matthias. Centuries later, Bram Stoker found inspiration in Vlad’s story while writing his novel Dracula.

Esztergom (EHS-tehr-gohm, pop. 29,000) is an unassuming town with a big Suzuki factory. You’d never guess it was the first capital of Hungary—until you see the towering 19th-century Esztergom Basilica, built on the site where István (Stephen) I, Hungary’s first Christian king, was crowned in A.D. 1000.

Esztergom’s boat dock is more convenient to the basilica than the bus or train stations are (can’t miss the basilica as you disembark—hike on up).

If arriving on the riverside bus from Visegrád, get off by the basilica (Iskola Utca stop)—not at the bus station.

If you’re coming by train, or on the overland bus from Budapest, you’re in for a longer walk. To reach the basilica on foot from the train station, allow at least 45 minutes. Continue in the same direction as the train tracks, and when the street forks, go straight along the residential Ady Endre utca. After a few minutes, you’ll pass the bus station, from which it’s 30 minutes farther to the basilica. Local buses run between the train station and the basilica roughly hourly. On Wednesdays and Fridays, an open-air market enlivens the street between the bus station and the center.

This basilica, on the site of a cathedral founded by Hungary’s beloved St. István, commemorates Hungary’s entry into the fold of Western Christendom. St. István was born in Esztergom, and on Christmas Day in the year 1000—shortly after marrying the daughter of the king of Bavaria and accepting Christianity—he was crowned here by a representative of the pope (for more on St. István, see here). Centuries later, after Esztergom had been retaken from the retreating Ottomans, the Hungarians wanted to build a “small Vatican” complex to celebrate the Hungarian Catholic Church and their triumphant return to the region. The Habsburgs who controlled the area at the time (and were also good Catholics) agreed, but did not want to be upstaged, so progress was sluggish. The Neoclassical basilica was erected slowly between 1820 and 1869, on top of the remains of a ruined hilltop castle. With a 330-foot-tall dome, this is the tallest building in Hungary.

Cost and Hours: Basilica—free, daily April-Oct 8:00-18:00, Nov-March 8:00-16:00. Tower climb—700 Ft, daily April-Oct 9:30-17:00, closed Nov-March and in bad weather. Crypt—200 Ft, daily March-Oct 9:00-17:00, Nov-Feb 10:00-16:00. Treasury—900 Ft, same hours as crypt. Tel. 33/402-354, www.bazilika-esztergom.hu.

Self-Guided Tour: Approaching the church is like walking toward a mountain—it gets bigger and bigger, yet you never quite reach it. In front of the church is a statue of Mary, the “Head, Mother, and Patron” of the Hungarian Church.

Self-Guided Tour: Approaching the church is like walking toward a mountain—it gets bigger and bigger, yet you never quite reach it. In front of the church is a statue of Mary, the “Head, Mother, and Patron” of the Hungarian Church.

Enter through the side door (on the left as you face the front of the basilica, under the arch). In the foyer, the stairway leading down to the right takes you to the crypt. This frigid space, with tree-trunk columns, culminates at the tomb of Cardinal József Mindszenty, revered and persecuted for standing up to the communist government (see sidebar). Also in the main chamber, look for original tombstones of 15th-century archbishops.

Back upstairs in the foyer, a stairway leads up to the church tower, which has fine views.

Enter the cavernous nave. Take in the enormity of the third-biggest church in Europe (by square footage). The lack of supporting pillars in the center of the church further exaggerates its vastness. This space was consecrated in 1856—before the entire building was finished—at a Mass with music composed by Franz Liszt.

As you face the altar, find the chapel on the left before the transept. This Renaissance Bakócz Chapel, part of an earlier church that stood here, predates the basilica by 350 years. It was commissioned by the archbishop during King Matthias Corvinus’ reign. The archbishop imported Italian marble-workers to create a fitting space to house his remains. Note the typically Renaissance red marble—the same marble that decorates Matthias’ palace at Visegrád. When the basilica was built, the chapel was disassembled into 1,600 pieces and rebuilt inside the new structure. The heads around the chapel’s altar were defaced by the Ottomans, who, as Muslims, believed that only God—not sculptors—can create man.

Continue to the transept. On the right transept wall, St. István offers the Hungarian crown to Mary—seemingly via an angelic DHL courier. There’s a depiction of this very church towering on the horizon. Mary is particularly important to Hungarians, because István—the first Christian king of Hungary—had no surviving male heir, so he appealed to Mary for help. (Eventually one of István’s cousins, András I, took the crown and managed to keep his kingdom in the fold of Christianity.)

And one more tour-guide factoid: Above the altar is what’s reputed to be the biggest single-canvas oil painting in the world. (It’s of the Assumption, by Michelangelo Grigoletti.)

Finish your visit with the treasury, to the right of the main altar (do this last, as you’ll exit outside the building; no English descriptions—pick up the illustrated listing at the entrance or, if they’re out, at the gift shop at the end). Head up the spiral staircase to view the impressive collection. After a display of vestments, you’ll wander a long hall tracing the evolution of ecclesiastical art styles: Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, and Modern. In the first (Gothic) section, find the giant drinking horns, used by kings at royal feasts. The second (Renaissance) section shows off some intricately decorated chalices. A close look at the vestments here shows that they’re embroidered with 3-D scenes, and slathered with gold and pearls. In the case on the wall, find the collection’s prized possession: an incredibly ornate example of Christ on the cross—but Jesus here bears an unmistakable likeness to King Matthias Corvinus. In the third (Baroque) and fourth (Rococo) sections, notice things getting frilly—and bigger and bigger, as the church got more money. The fifth (Modern) section displays an array of kissable bishop rings.

The exit takes you out to a Danube-view terrace. For the best river-bend view, walk a hundred yards or so downstream (right) to the modern statue of St. István. It shows Hungary’s favorite saint being crowned by the local bishop after converting to Christianity; St. István symbolically holds up the arches of the Hungarian Church. (Until this statue was built in 2003, this was the choice spot for Esztergom teens to kiss.) Between the statue and the river, you can see the ruins of an Ottoman bath and the evocative stub of a ruined minaret, with its spiral staircase exposed and going nowhere.

That’s Štúrovo, Slovakia, across the river, connected to Hungary by the Mária Valéria Bridge—destroyed in World War II and rebuilt only in 2001. Before its reconstruction, no bridges spanned the Danube between Budapest and Bratislava. If you have time, you can walk or drive across the bridge to Slovakia for the best views back to this basilica (no passport checks).

Near the Basilica: This hilltop was once heavily fortified, and some ruins of its castle survive—now part of the Castle Museum next to the basilica (opposite side from the István statue). In 2007, restorers discovered a fresco of the four virtues, likely by Sandro Botticelli. The complex also includes the chapel where St. István was supposedly born. Unfortunately, both of these areas are closed for restoration (work has stalled due to lack of funding). For now, all there is to see is lots of dusty old exhibits about arcane Hungarian history, from the Stone Age through the Ottoman period (500-Ft “walking ticket” to tour the grounds; 1,300 Ft to join a Hungarian tour of the interior, or pay 500 Ft extra if there’s an English tour; April-Oct Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, Nov-March Tue-Sun 10:00-16:00, closed Mon year-round, www.mnmvarmuzeuma.hu).

A few restaurants cluster near the basilica (including one built into the fortifications underneath it), but these cater to tour groups and serve mediocre food. It’s more interesting to venture down the hill to the Víziváros (“Water Town”) neighborhood on the riverbank below the basilica. This area has a pleasant, old-town ambience and some fine local-style eateries. You can either walk down on the path from the basilica, or (in summer) catch a handy tourist train for 500 Ft.

For connections, see “Getting Around the Danube Bend” on here. When choosing between the riverside bus and the direct overland bus, note that the overland bus—while faster and offering different scenery—departs much farther from the basilica than the riverside bus.

The easiest choice is to retrace your route on road #11 around the Bend to Budapest. But to save substantial time and see different scenery, I prefer “cutting the Bend” and taking a shortcut through the Pilis hills (takes just over an hour total, depending on traffic).

To Cut the Bend: From the basilica in Esztergom, continue along the main road #11 (away from Budapest) to the roundabout with the round, yellow, Neoclassical church (built as a sort of practice before they started on the basilica). Here you can choose your exit: If you exit toward Budapest/Dorog, it’ll take you back on road #11 for a while, then route you onto the busier road #10 (which can have heavy traffic—especially trucks—on weekdays). Better yet, if you head for Dobogókő, you’ll follow a twistier but faster route via the town of Pilisszentkereszt to Budapest. After about 30 minutes on this road, in the town of Pomáz, follow signs to road #11 to the left, then turn right toward Budapest at the next fork to join road #11 into the city. (Don’t follow signs at the Pomáz intersection for Budapest, which takes you along a more heavily trafficked road.)

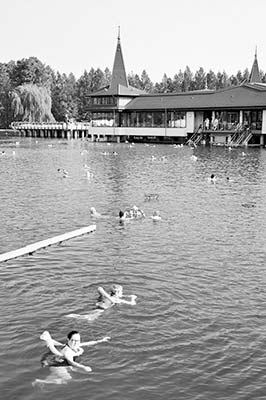

The destinations I’ve covered in depth will keep you busy for at least two weeks in Hungary. But if you have more time or a special interest, there’s much more of Hungary to experience. Here are some ideas to get you started on planning a visit to other parts of the country.

More than half of Hungary (essentially everything southeast of the Danube) constitutes the Great Hungarian Plain, or Puszta. Broad, flat, desolate, and parched in the late summer and autumn, the Great Hungarian Plan is the Magyar version of Big Sky Country. Most of the sights listed here (except Hortobágy National Park) line up along the M-5 expressway south of Budapest; a train line also connects them (trains depart Budapest hourly, 1.5 hours to Kecskemét, 2.5 hours to Szeged).

If the idea of the Lázár Lovaspark horse show (described earlier) intrigues you, consider experiencing a similar performance in its original setting, on the Great Hungarian Plain. Various farms around the Puszta put on these shows frequently in summer, and by request off-season. The various options all hew pretty close to the same format: performance, tour of stables and farm, carriage ride, and sometimes a traditional goulash lunch from a copper pot over an open fire. (Read the description on here so you know roughly what to expect.) One popular choice is in the village of Bugac, deep in the countryside roughly halfway between Kecskemét and Szeged (about 45 minutes from either town; www.bugacpuszta.hu). Another option is in Hortobágy National Park, two hours’ drive due east of Budapest (www.hnp.hu). It’s important to call or email them in advance to confirm the schedule and let them know you’re coming.

This low-impact, charming city (pop. 115,000, www.kecskemet.hu) is handy for a stretch-your-legs break on your drive south (about an hour south of Budapest on M-5; follow Centrum signs and park in the garage for the big Malom shopping mall adjacent to the main square).

Kecskemét (KETCH-keh-mayt) has a downtown core made up of a series of wide, interlocking squares with a mix of beautiful Art Nouveau and Secessionist architecture, as well as some unfortunate communist-era drabness. Sometimes called the “garden city,” Kecskemét is ringed by inviting parks and greenbelts. The city is also known for producing wine as well as apricot brandy (barackpálinka). While there aren’t many “sights” to enter, Kecskemét gives you a taste of a largely untouristy midsize city.

If taking a lunch break in Kecskemét, do it at Kecskeméti Csárda, a traditional, almost folksy, borderline kitschy restaurant that hides just a few blocks off of the main drag. The service is warm, and the Hungarian specialties are executed as well here as anywhere (daily for lunch and dinner, Kölcsey utca 7, tel. 76/488-686, www.kecskemeticsarda.hu).

Near Kecskemét: Just off of M-5 between Kecskemét and Szeged, Ópusztaszer Heritage Park celebrates those original Hungarians who arrived in the Great Plain more than 11 centuries ago: the Magyars. This complex has an open-air museum of traditional village architecture, a wrap-around panorama painting of the arrival of the Magyars, a cluster of “Csete-yurts” in the distinctive Organic architecture style, and frequent special events that include equestrian shows (www.opusztaszer.hu).

Szeged (SEH-gehd; pop. 160,000, including 23,000 university students) is the leading city of the Great Hungarian Plain. It boasts a livable town center with gorgeous Art Nouveau architecture, some impressive sights and baths, and a fascinating multiethnic collage.

Historically and culturally, Szeged is southern Hungary’s main crossroads. It sits along the Tisza River, at the intersection of three countries: From here, Serbia and Romania are both within a 15-minute drive. Remember that well into the 20th century, Hungary was triple the size it is now, and Szeged was quite central rather than a southern outpost. The neighboring regions of Vojvodina (now in Serbia) and Transylvania (now in Romania) still have substantial Hungarian populations.