Várhegy

Hungarian National Gallery (Magyar Nemzeti Galéria)

Hungarian National Gallery (Magyar Nemzeti Galéria)

Budapest History Museum (Budapesti Történeti Múzeum)

Budapest History Museum (Budapesti Történeti Múzeum)

Matthias Church (Mátyás-Templom)

Matthias Church (Mátyás-Templom)

Fishermen’s Bastion (Halászbástya)

Fishermen’s Bastion (Halászbástya)

Remains of St. Mary Magdalene Church

Remains of St. Mary Magdalene Church

Once the seat of Hungarian royalty, and now the city’s highest-profile tourist zone, Castle Hill is a historic spit of land looming above the Buda bank of the Danube. Scenic from afar, but (frankly) a bit soulless from up close, it’s best seen quickly. The major landmarks are the huge, green-domed Royal Palace at the south end of the hill (housing a pair of museums) and the frilly-spired Matthias Church near the north end (with the hill’s best interior). In between are tourist-filled pedestrian streets and historic buildings. This walk gives you the lay of the land and leads you to the hill’s most worthwhile attractions and museums, including the Matthias Church, the Fishermen’s Bastion, the Hungarian National Gallery, and the WWII-era Hospital in the Rock. You’ll also appreciate the bird’s-eye views that a visit to Castle Hill offers across the Danube to Pest.

(See "Castle Hill Walk" map, here.)

Length of This Walk: Allow about two hours, including a visit to Matthias Church; you’ll need more time for additional sights (especially the Hungarian National Gallery and the Hospital in the Rock).

When to Visit: Castle Hill is packed with tour groups in the morning, but it’s much less crowded in the afternoon. Since restaurants up here are touristy and a bad value, Castle Hill is an ideal after-lunch activity.

Getting There: The Metró and trams won’t take you to the top of Castle Hill. Instead, you can hike, taxi, catch a bus, or ride the funicular.

For most visitors, the easiest bet is to hop on bus #16, with handy stops in both Pest (at the Deák tér Metró hub—on Harmincad utca alongside Erzsébet tér, use exit “E” from the station underpass; and at Széchenyi tér at the Pest end of the Chain Bridge) and Buda (at Clark Ádám tér at the Buda end of the Chain Bridge—across the street from the lower funicular station, and much cheaper than the funicular). Or you can go via Széll Kálmán tér (on the M2/red Metró line or by taking tram #4 or #6 around Pest’s Great Boulevard); from here, bus #16, as well as buses #16A and #116, head up the hill (at Széll Kálmán tér, catch the bus just uphill from the Metró station—in front of the red-brick, castle-looking building). All buses stop at Dísz tér, at the crest of the hill, about halfway along its length (most people on the bus will be getting off there, too). From Dísz tér, cross the street and walk five minutes along the row of flagpoles toward the green dome, then bear left to find the big Turul bird statue at the start of this walk.

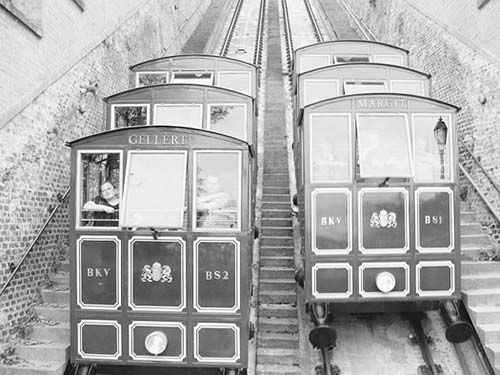

The funicular (sikló, SHEE-kloh), which lifts visitors from the Chain Bridge to the top of Castle Hill, is a Budapest landmark. Built in 1870 to provide cheap transportation to Castle Hill workers, today it’s a pricey little tourist trip. Read the fun first-person history in glass cases at the top station (1,200 Ft one-way, 1,800 Ft round-trip, not covered by transit pass, daily 7:30-22:00, departs every 5-10 minutes, closed for maintenance every other Mon). It leaves you right at the Turul bird statue, where this walk begins.

If you’d like to hike up, the most interesting approach is through the castle gardens called Várkert Bazár. From the monumental gateway facing the Danube embankment (just below the Royal Palace, between the Clark Ádám tér and Döbrentei tér stops for trams #19 and #41), head up the stairs into a fine Renaissance garden, then walk (or ride the long escalator) about two-thirds of the way up the hill. From there, a series of two elevators takes you directly up to the palace promenade with minimal climbing—or you can take the scenic route, walking up the delightful switchback ramparts. Either way, you’ll wind up at the Royal Palace (begin the walk at  , the viewpoint in front of the palace, and see the Turul bird on your way back across the hill later). For more on Várkert Bazár, see here.

, the viewpoint in front of the palace, and see the Turul bird on your way back across the hill later). For more on Várkert Bazár, see here.

To leave the hilltop, most visitors find it easiest just to walk down after their visit (see the end of this tour). But if you’ll be taking the bus down, it’s smart to buy tickets for the return trip before you ascend Castle Hill—the only place to buy them up top is the post office near Dísz tér (Mon-Fri until 16:00, closed Sat-Sun).

Changing of the Guard: On the hour, uniformed soldiers do a changing-of-the-guard ceremony at Sándor Palace (the president’s residence, near the top of the funicular), with a more elaborate show at 12:00. While not worth planning your day around (it’s just a few guys in modern military uniforms slinging rifles), it’s fun to watch if you happen to be nearby.

Hungarian National Gallery: 1,400 Ft, may be more for special exhibits, 500 Ft extra to take photos, audioguide-800 Ft, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, Szent György tér 2.

Budapest History Museum: 1,800 Ft, audioguide-1,200 Ft; March-Oct Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, Nov-Feb Tue-Sun 10:00-16:00, closed Mon year-round; Szent György tér 2.

Matthias Church: 1,200 Ft, Mon-Fri 9:00-17:00, Sat 9:00-13:00, Sun 13:00-17:00, Szentháromság tér 2.

Fishermen’s Bastion: 700 Ft, daily mid-March-mid-Oct 9:00-19:30; after closing time and off-season, no tickets are sold but bastion is open and free to enter; Szentháromság tér 5.

Eateries: In the Eating in Budapest chapter, I’ve suggested a few lunch options up here—but for more (and cheaper) choices, head just downhill to Batthyány tér.

Starring: Budapest’s most historic quarter, with a palace (and a top collection of Hungarian art), a gorgeous church interior, sweeping vistas over city rooftops, and layers of history.

This hilltop has a history as complex and layered as Hungary’s. Originally, the main city of Hungary wasn’t Buda or Pest, but Esztergom (just up the river—see here). In the 13th century, Tatars swept through Eastern Europe, destroying much of Hungary. King Béla IV, who was forced to rebuild his kingdom, re-envisioned Buda as a fortified hilltop town, and moved the capital to this more protected location in the interior of the country. The city has dominated the region ever since.

Over the years, the original Romanesque fortress here was rebuilt and accentuated with a textbook’s worth of architectural styles: Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque. It was one of Europe’s biggest palaces by the early 15th century, when King Mátyás (Matthias) Corvinus made the palace even more extravagant, putting Buda—and Hungary—on the map.

Just a few decades later, the invading Ottomans occupied Buda and turned the palace into a military garrison. When the Habsburgs laid siege to the hill for 77 days in 1686, gunpowder stored in the cellar exploded, destroying the palace. The Habsburgs (with a motley, pan-European army that included few Hungarians) took the hill, but Buda was deserted and in ruins. The town was resettled by Austrians, who built a new Baroque palace, hoping that the Habsburg monarch would move in—but none ever did. The useless palace again became a garrison, then the viceroy’s residence. It was damaged yet again during the 1848 Revolution, but was repaired and continued to grow right along with Budapest’s prominence.

As World War II drew to a close, Budapest became the front line between the Nazis and the approaching Soviets. The labyrinth of natural caves under the hill was even adapted for use as a secret military hospital (the tourable Hospital in the Rock). The Nazis, who believed the Danube to be a natural border for their empire, destroyed bridges across the river and staged a desperate “last stand” on Castle Hill. The Red Army laid siege to the hill for 100 days. They eventually succeeded in taking Budapest...but the city—and the hill—were devastated once again. Since then, the Royal Palace and hilltop town have been rebuilt once more, with a mix-and-match style that attempts, with only some success, to evoke the site’s grand legacy.

• Orient yourself from the top of the funicular, enjoying the views over the Danube. (We’ll get a full visual tour from a better viewpoint later.) At the top of the nearby staircase, notice the giant bird that looks like a vulture. This is the...

Turul Bird

Turul BirdThis mythical bird of Magyar folktales supposedly led the Hungarian migrations from the steppes of Central Asia in the ninth century. He dropped his sword in the Carpathian Basin, indicating that this was to be the permanent home of the Magyar people. While the Hungarians have long since integrated into Europe, the Turul remains a symbol of Magyar pride. During a surge of nationalism in the 1920s, a movement named after this bird helped revive traditional Hungarian culture. And today, the bird is invoked by right-wing nationalist politicians.

The imposing palace on Castle Hill barely hints at the colorful story of this hill since the day that the legendary Turul dropped his sword. It was once the top Renaissance palace in Europe...but that was several centuries and several versions ago. The current palace—a historically inaccurate, post-WWII reconstruction—is a loose rebuilding of previous versions. It’s big but soulless. The most prominent feature of today’s palace—the green dome—didn’t even exist in earlier versions. Fortunately, the palace does house some worthwhile museums (described later), and boasts the fine terrace you’re strolling on, with some of Budapest’s best views.

Walk all the way down the terrace to the big equestrian statue in front of the dome. This depicts Eugene of Savoy, a French general who had great success fighting the Hungarians’ hated enemies, the Ottomans. First he helped break the Turkish Siege of Vienna in 1683, then he led the successful Siege of Belgrade in 1717; together, these victories marked the beginning of the end of the Ottoman advance into Europe. Eugene—who fought under three successive Habsburg emperors—was hugely popular across a Europe that was terrified of the always-looming Ottoman threat. He was the Patton or Eisenhower of his day—a great war hero admired and appreciated by all. This explains why a Frenchman gets a place of honor in front of Hungary’s Royal Palace.

• With the palace at your back, notice the long, skinny promontory sticking out from Castle Hill (on your right). Walk out to the tip of that promontory to enjoy Castle Hill’s best...

Pest Panorama

Pest PanoramaFrom here, you can see how topographically different the two halves of Budapest really are. The hill you’re on is considered one of the last foothills of the Alps, which ripple from here all the way to France. But immediately across the Danube, everything is oh so flat. Here begins the so-called Great Hungarian Plain, which comprises much of the country—a vast expanse that stretches all the way to Asia. For this reason, Budapest has historically been thought of as being on the bubble between West and East. From the ancient Romans to Adolf Hitler, many past rulers have viewed the Danube through Budapest as a natural border for Europe.

Scan Pest on the horizon, from left to right. Tree-filled Margaret Island, a popular recreation spot, sits in the middle of the Danube. Following the Pest riverbank, you can’t miss the spiny Parliament, with its giant red dome. Straight ahead, you enjoy views of the Chain Bridge, with Gresham Palace and the 1896-era St. István’s Basilica lined up just beyond it. (The Parliament and St. István’s are both exactly 96 meters tall, in honor of the auspicious millennium celebration in 1896—see here.) The Chain Bridge cuts downtown Pest in two: The left half, or “Leopold Town,” is administrative, with government ministries, embassies, banks, and so on; the right half is the commercial and touristic center of Pest, with the best riverside promenade. (Each of these is covered by a different self-guided walk in this book.) To the right is the white Elisabeth Bridge, named for the Austrian empress (“Sisi”) who so loved her Hungarian subjects. Downriver (to the right) is the green Liberty Bridge, formerly named for Elisabeth’s hubby Franz Josef. (If you squint, you might be able to see the Turul birds that top the pillars of this bridge.) And the tall hill to the right, named for the martyred St. Gellért (who patiently attempted to convert the rowdy Magyars after their king adopted Christianity), is topped by the Soviet-era Liberation Monument. At your feet, to the right, sprawl the inviting Renaissance gardens of the recently restored Várkert Bazár terrace (described on here).

• Head back to the statue on the terrace. Facing Eugene’s rear end is the main entrance to the...

Hungarian National Gallery (Magyar Nemzeti Galéria)

Hungarian National Gallery (Magyar Nemzeti Galéria)The best place in Hungary to appreciate the works of homegrown artists, this art museum offers a peek into the often-morose Hungarian worldview. The collection includes a remarkable group of 15th-century, wood-carved altars from Slovakia (then “Upper Hungary”); piles of gloomy canvases dating from the dark days after the failed 1848 Revolution; several works by two great Hungarian Realist painters, Mihály Munkácsy and László Paál; and paintings by the troubled, enigmatic, and recently in-vogue Post-Impressionist Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka. While not quite a must-see, the collection’s highlights can be viewed quickly. For a self-guided tour of the top pieces, see here.

• Head back out to the Eugene statue and face the palace. Go through the passage to the right of the National Gallery entrance (next to the café). You’ll emerge into a courtyard decorated with the...

King Matthias Fountain

King Matthias FountainThis fountain depicts King Matthias enjoying one of his favorite pastimes, hunting. (Notice the distinctive, floppy-eared Hungarian hound dog, or Vizsla.) At the bottom of the fountain, the guy on the left is Matthias’ scribe, while the woman on the right is Ilonka (“The Beautiful”). While Matthias was on an incognito hunting trip, he wooed Ilonka, who fell desperately in love with him—oblivious to the fact he was the king. When he left suddenly to return to Buda, Ilonka tracked him down and realized who he was. Understanding that his rank meant they could never be together, Ilonka committed suicide. This is typical of many Hungarian legends, which tend to be melancholic and end badly.

• On that cheerful note, go around the right side of the fountain and through the passage, into the...

Palace Courtyard

Palace Courtyard

Budapest History Museum (Budapesti Történeti Múzeum)

Budapest History Museum (Budapesti Történeti Múzeum)This earnest but dusty collection strains to bring the history of this city to life. If Budapest really intrigues you, this is a fine place to explore its history. Otherwise, skip it. The dimly lit fragments of 14th-century sculptures, depicting early Magyars, allow you to see how Asian those original Hungarians truly looked. The “Budapest: Light and Shadow” exhibit deliberately but effectively traces the union between Buda and Pest. Rounding out the collection are exhibits on prehistoric residents and a sprawling cellar that unveils fragments from the oh-so-many buildings that have perched on this hill over the centuries. For a rundown of its collection, see here.

Leaving the palace courtyard, walk straight up the slight incline. In good weather, you might see an opportunity to try your hand at shooting an old-fashioned bow and arrow. Then you’ll pass under a gate with a raven holding a ring in its mouth (a symbol of King Matthias). As you continue along the line of flagpoles, the big white building on your right (near the funicular station) is the Sándor Palace. This mansion underwent a very costly renovation under the previous Hungarian prime minister, who hoped to make it his residence. But in 2002, the same year it was finished, he lost his bid for re-election. The spunky new PM refused to move in. By way of compromise, this is now the president’s office. This is where you can see the relatively low-key changing of the guard each hour on the hour, with a special show at noon.

After Sándor Palace is the yellow former Court Theater (Várszínház), which has seen many great performances over the centuries—including a visit from Beethoven in 1800. Until recently, this housed the National Dance Theater. But current Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán (not known for humble gestures) grew jealous of the president’s swanky digs, kicked out the dancers, and renovated this building as the prime minister’s residence. The bizarre back-and-forth—one PM wanting to live at the castle, the next refusing, and the next again wanting to—is perfectly illustrative of the swaying pendulum that is Hungarian politics.

In the field in the middle of this terrace, you’ll notice the ruins of a medieval monastery and church. Along the left side (past the flagpoles) is the ongoing excavation of the medieval Jewish quarter—more reminders that most of what you see on today’s Castle Hill has been destroyed and rebuilt many times over.

Notice the bridge on the left, crossing over some of those ruins, as well as a trench around the castle wall. Go over that bridge to a viewpoint for a look at the Buda Hills—the “Beverly Hills” of Hungary, draped with orchards, vineyards, and the homes of the wealthiest Budapesters.

Walk along this outer terrace, enjoying the views, then hook right to reach the former Ministry of War. Until 2013, this was still a bombed-out shell, with war damage from both World War II and the brutal Soviet response to the 1956 Uprising (see here). Now it has been converted into a fine space for special exhibits—head to the front door to see what’s on (likely 2,000 Ft, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon). To the left of the door, you can see the faint bullet holes and shrapnel scars—intentionally left here as a memorial (see the Memento 1944-1945 plaque).

Cross the street in front of the former Ministry of War to reach Dísz tér (Parade Square). Here you’ll see convenient bus stops for connecting to other parts of Budapest (bus #16, #16A, or #116 to Széll Kálmán tér; or bus #16 to the Pest side of the Chain Bridge). On the left is a handy post office (bus tickets sold here Mon-Fri before 16:00, closed Sat-Sun). On the right, behind the yellow wall, is a courtyard with an open-air Hungarian folk-art market. While it’s fun to browse, prices here are high (haggle away). The Great Market Hall has a better selection and generally lower prices (see here).

Continue straight uphill on Tárnok utca (noticing, on the left, the recommended Vár Bistro—a handy lunch cafeteria). This area often disappoints visitors. After being destroyed by Ottomans, it was rebuilt in sensible Baroque, lacking the romantic time-capsule charm of a medieval old town. But if you poke your head into some courtyards, you’ll almost always see some original Gothic arches and other medieval features.

As you continue along, ponder the fact that there are miles of caves burrowed under Castle Hill—carved out by water, expanded by the Ottomans, and used by locals during the siege of Buda at the end of World War II. If you’d like to spelunk under Castle Hill, there are two different sightseeing options: To learn about how the caves were used during the 20th century, it’s worth going on the lengthy Hospital in the Rock tour (see here); for just a quick look, you can check out the touristy Buda Labyrinth cave, with a sparse, hokey historical exhibit (see here).

As you approach the plague column, on your left at #18 is the low-profile entrance to the  Golden Pharmacy Museum (dark-orange building). Consider dipping into this modest three-room collection of historic pharmaceutical bric-a-brac, including a cute old pharmacy counter and an alchemist’s lab (500 Ft, borrow English descriptions, Tue-Sun 10:30-18:00, closed Mon, last entry 30 minutes before closing, Tárnok utca 18).

Golden Pharmacy Museum (dark-orange building). Consider dipping into this modest three-room collection of historic pharmaceutical bric-a-brac, including a cute old pharmacy counter and an alchemist’s lab (500 Ft, borrow English descriptions, Tue-Sun 10:30-18:00, closed Mon, last entry 30 minutes before closing, Tárnok utca 18).

Finally, you’ll come to a little park. The white, circular building in the park, marked TourInform, is a TI that can answer questions and has a handy pictorial map of the castle area (daily 10:00-18:00).

Across the street from the park (on the left), the CBA grocery store sells reasonably priced cold drinks, and has a coffee shop upstairs (open daily). A good spot for dessert is just around the corner: Rétesbár, selling strudel (rétes) with various fillings for 300 Ft each (just down the little lane—Balta köz—next to the grocery store, daily 8:00-19:30).

Just beyond the park, a warty plague column from 1713 marks Szentháromság tér (Holy Trinity Square), the main square of old Buda.

• Dominating the square is the...

Matthias Church (Mátyás-Templom)

Matthias Church (Mátyás-Templom)Budapest’s best church has been destroyed and rebuilt several times in the 800 years since it was founded by King Béla IV. Today’s version—renovated at great expense in the late 19th century and restored after World War II—is an ornately decorated lesson in Hungarian history. The church’s actual name is the Church of Our Lady, or the Coronation Church (because its unofficial namesake, Matthias Corvinus, isn’t a saint, it can’t be formally named for him). But everyone calls it the Matthias Church, for the popular Renaissance king who got married here—twice.

Self-Guided Tour: Examine the exterior. While the nucleus of the church is Gothic, most of what you see outside—including the frilly, flamboyant steeple—was added for the 1896 celebrations. At the top of the stone corner tower facing the river, notice the raven—the ever-present symbol of King Matthias Corvinus.

Self-Guided Tour: Examine the exterior. While the nucleus of the church is Gothic, most of what you see outside—including the frilly, flamboyant steeple—was added for the 1896 celebrations. At the top of the stone corner tower facing the river, notice the raven—the ever-present symbol of King Matthias Corvinus.

Buy your ticket across the square from the church’s side door, at the ticket windows embedded in the wall. Then enter the church. The good English descriptions posted throughout will amplify this tour.

The sumptuous interior is wallpapered with gilded pages from a Hungarian history textbook. Different eras are represented by symbolic motifs. Entering the side door, turn left and go to the back end of the church. The wall straight ahead represents the Renaissance, with a giant coat of arms of beloved King Matthias Corvinus. (The tough guys in armor on either side are members of his mercenary Black Army, the source of his power.) Notice another raven, with a ring in its beak.

Work your way clockwise around the church. The first chapel (in the back corner, to the left as you face the closed main doors)—the Loreto Chapel—holds the church’s prize possession: a 1515 statue of Mary and Jesus. Anticipating Ottoman plundering, locals walled over its niche. The occupying Ottomans used the church as their primary mosque—oblivious to the precious statue hidden behind the plaster. Then, a century and a half later, during the siege of Buda in 1686, gunpowder stored in the castle up the street detonated, and the wall crumbled. Mary’s triumphant face showed through, terrifying the Ottomans. Supposedly this was the only part of town taken from the Ottomans without a fight.

Facing the doors, look to the top of the stout pillar on the right to see a carved capital showing two men gesturing excitedly at a book. Dating from 1260, these carvings are some of the earliest surviving features in this church, which has changed much over the centuries.

As you look down the nave, notice the banners. They’ve hung here since the Mass that celebrated Habsburg monarch Franz Josef’s coronation at this church on June 8, 1867. In a sly political compromise to curry favor in the Hungarian part of his territory, Franz Josef was “emperor” (Kaiser) of Austria, but only “king” (König) of Hungary. (If you see the old German phrase “K+K”—still used today as a boast of royal quality—it refers to this “König und Kaiser” arrangement.) So, after F. J. was crowned emperor in Vienna, he came down the Danube and said to the Hungarians, “King me.” (For more on the K+K system, see here.)

Continue circling around the church. Along the left aisle (toward the main altar from the gift shop) is the altar of St. Imre, the son of the great King (and later Saint) István—who is standing to the left of him. This heir to the Hungarian throne was mysteriously killed by a boar while hunting when he was only 19 years old. Though Imre didn’t live long enough to do anything important, he rode his father’s coattails to sainthood. Lacking a direct heir, István dedicated his country to Mary—which is why she’s wearing the Hungarian crown in this altar, and at this church’s main one (which we’ll see soon).

The next chapel is the tomb of Béla III, utterly insignificant except that this is one of only two tombs of Hungarian kings that still exist in the country. The rest—including all of the biggies—were defiled by the Ottomans.

Up next to the main altar is the chapel of László—King István’s nephew, who stepped in as king of Hungary when the rightful heir, Imre, was killed.

Now stand at the modern altar in the middle of the church, and look down the nave to the main altar. Mary floats above it all, and hovering over her is a full-scale replica of the Hungarian crown, which was blessed by Pope John Paul II. More than a millennium after István, Mary still officially wears this nation’s crown.

Climb the circular stone staircase (in the corner, near the chapel of László) up to the gallery. Walk along the royal oratory to a small room that overlooks the altar area. Here, squeezed in the corner between luxurious vestments, is another replica of the Hungarian crown (the original is under the Parliament’s dome, and described on here). Then you’ll huff up another staircase for more views down over the nave, and an exhibit on the church’s recent restoration, displaying original statues and architectural features. You’ll exit back down into the nave.

• Back outside, at the end of the square next to the Matthias Church, is the...

Fishermen’s Bastion (Halászbástya)

Fishermen’s Bastion (Halászbástya)This Neo-Romanesque fantasy rampart offers beautiful views over the Danube to Pest. In the Middle Ages, the fish market was just below here (in today’s Víziváros, or “Water Town”), so this part of the rampart actually was guarded by fishermen. The current structure, however, is completely artificial—yet another example of Budapest sprucing itself up for 1896. Its seven pointy towers represent the seven Magyar tribes. The cone-headed arcades are reminiscent of tents the nomadic Magyars called home before they moved west to Europe.

Paying 700 Ft to climb up the bastion makes little sense. Enjoy virtually the same view through the windows (left of café) for free. (The café offers a scenic break if you don’t mind the tour groups.) There’s a pay WC to the right of the bastion.

Explore the full length of the bastion, and you’ll find that several other sections are also open and free to the public—as well as more scenic cafés, sometimes with live “Gypsy” music. Note that the (free) grand staircase leading down from the bastion offers a handy shortcut to the Víziváros neighborhood and Batthyány tér (for affordable restaurants there, see here).

Tucked around the far side of the bastion, at the back of a pastry shop in the modern, glassy building, is the Szabó Marzipan Museum, where you can pay 400 Ft to see two rooms crammed full of little sculptures created from this almond-paste confection (daily 9:00-18:00). While it’s not as impressive as the similar sight in Eger (see here), it’s worth a peek if you’re curious.

• Between the bastion and the church stands a...

Statue of St. István

Statue of St. István

• Directly across from Matthias Church is a charming little street called...

Szentháromság Utca

Szentháromság UtcaHalfway down this street on the right, look for the venerable, recommended Ruszwurm café—the oldest in Budapest (see listing on here). At the end of the street is an equestrian statue of the war hero András Hadik. If you examine the horse closely, you’ll see that his, ahem, undercarriage has been polished to a high shine. Local students rub these for good luck before a big exam. I guess you could say students really have a ball preparing for tests.

Continue out to the terrace and appreciate more views of the Buda Hills. If you go down the stairs here, then turn right up the street, you’ll reach the entrance of the World War II-era Hospital in the Rock, which you can tour to learn about the Nazi and Cold War era of Castle Hill (excellent tours at the top of each hour, described on here).

• Retrace your steps back to Matthias Church. Some visitors will have had their fill of Castle Hill; if so, you can make a graceful exit down the big staircase below the Fishermen’s Bastion. You’ll wind up in Víziváros, on the embankment.

But if you’d like to extend your walk to the northern part of Castle Hill, start at the plague column, and go up the street next to the modern building. This is the...

Hilton Hotel

Hilton HotelBuilt in 1976, the Hilton was the first plush Western hotel in town. Before 1989, it was a gleaming center of capitalism, offering a cushy refuge for Western travelers and a stark contrast to what was, at the time, a very gloomy city. To minimize the controversy of building upon so much history, architects thoughtfully incorporated the medieval ruins into their modern design. Halfway down the hotel’s facade (after the first set of doors, at the base of the tower), you’ll see fragments of a 13th-century wall, with a monument to King Matthias Corvinus. After the wall, continue along the second half of the Hilton Hotel facade. Turn right into the gift-shop entry, and then go right again inside the second glass door. Through yet another glass door, stairs on the left lead down to a reconstructed 13th-century Dominican cloister (now housing a wine cellar). For an even better look at what was here back then, continue past the cloister stairs and enter the lobby café-bar. Look out the back windows to see fragments of the 13th-century Dominican church incorporated into the structure of the hotel. If you stood here eight centuries ago, you’d be looking straight down the church’s nave. You can even see tomb markers in the floor.

Back out on the street, cross the little park and duck into the entryway of the Fortuna Passage. Along the passageway to the courtyard, you can see the original Gothic arches of the house that once stood here. In the Middle Ages, every homeowner had the right to sell wine without paying taxes—but only in the passage of his own home. He’d set up a table here, and his neighbors would come by to taste the latest vintage. These passageways evolved into very social places, like the corner pub.

Leaving the passage, turn left down Fortuna utca and walk toward the mosaic roof (passing the recommended 21 Magyar Vendéglő on your right—a good place for an upscale meal). Reaching the end of the street, look right to see the low-profile Vienna Gate. If you go through it and walk for about 10 days, you’ll get to Vienna. (For now, settle for climbing up to the top for a view of some of Buda’s residential neighborhoods.) Just inside the Vienna Gate, notice the bus stop—handy for leaving Castle Hill when you’re finished.

Remains of St. Mary Magdalene Church

Remains of St. Mary Magdalene ChurchThis was once known as the Kapisztrán Templom, named after a hero of the Battle of Belgrade in 1456, an early success in the struggle to keep the Ottomans out of Europe. (King Matthias’ father, János Hunyadi, led the Hungarians in that battle.) The pope was so tickled by the victory that he decreed that all church bells should toll at noon in memory of the battle—and, technically, they still do. (Californians might recognize Kapisztrán’s Spanish name: San Juan Capistrano.) This church was destroyed by bombs in World War II, though no worse than Matthias Church. But, since this part of town was depopulated after the war, there was no longer a need for a second church. The remains of the church were torn down, the steeple was rebuilt as a memorial, and a carillon was added—so that every day at noon, the bells can still toll...and be enjoyed by the monument of János Kapisztrán, just across the square.

• Our walk is finished, but there are a few more options nearby. You can walk out to the terrace just beyond the big building for another look at the Buda Hills. From here, just to the right (near the flagpole), is the entrance to the Museum of Military History, with a mountain of army-surplus artifacts from Hungary’s gloriously unsuccessful military past (described on here). If you continue around the terrace past the museum, at the northern point of Castle Hill you’ll find an old Turkish grave, honoring a pasha who once ruled here during Ottoman times.

If you’re ready to leave Castle Hill, you can backtrack to the Fishermen’s Bastion and walk down the grand staircase there (into the Víziváros neighborhood). Or, from the square just inside Vienna Gate, you can catch bus #16, #16A, or #116 to Széll Kálmán tér—or head out through the gate and follow the road downhill. You’ll run into bustling Széll Kálmán tér, which has a handy Metró stop (M2/red line) and the huge, modern, popular Mammut shopping complex.