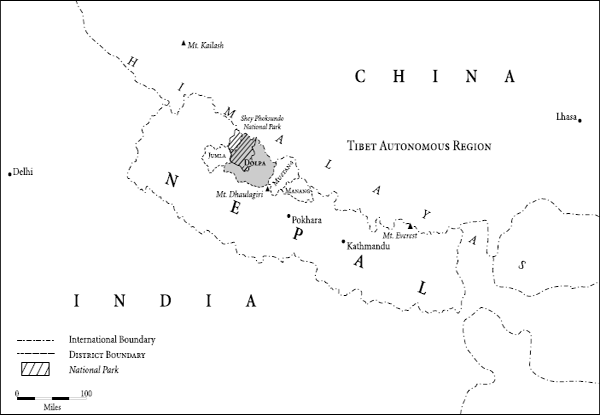

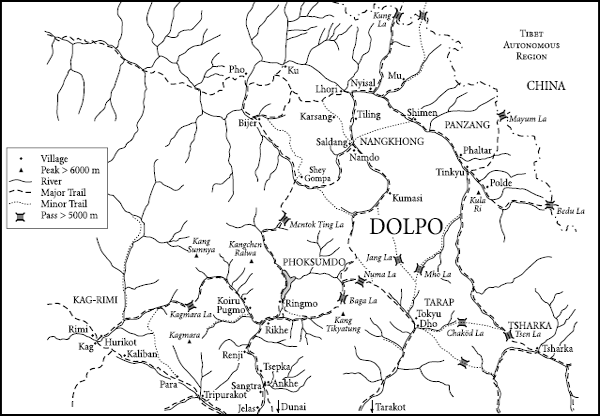

This is a story of Dolpo, a culturally Tibetan region in western Nepal. Dolpo encompasses four valleys—Panzang, Nangkhong, Tsharka, Tarap—and a people who share language, religious and cultural practices, history, and a way of life.1 Its valleys are clustered along the border of Nepal and the Tibet Autonomous Region (China); Dolpo’s residents refer to this entire region as the area bounded by the Tibetan Plateau (to the north), the Mustang District (east), Tsharka village (south), the watershed above Phoksumdo Lake (west), and the Mugu Karnali River (northwest).2 Dolpo is home to some of the highest villages on Earth; almost 90 percent of the region lies above 3,500 meters in elevation (Lama, Ghimire, and Aumeeruddy-Thomas 2001). Its inhabitants wrest survival from this inhospitable landscape by synergizing agriculture, animal husbandry, and trade.

The population of Dolpo numbers less than 5,000 people, making it one of the least densely populated areas of Nepal. With life expectancy at a mere fifty years, more than 90 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, the literacy level is negligible, and family planning is almost nonexistent.3 Administratively, the valleys of Dolpo are located in the northern reaches of Nepal’s largest district, Dolpa.4 This region is also referred to as “Upper” Dolpo by His Majesty’s Government of Nepal, a designation which has restricted foreigners from traveling extensively in this area.

Figure 1 Regional map for Nepal, Tibet, and China

This book describes Dolpo—focusing especially on the period after 1959—and traces how pastoralists living in the trans-Himalaya have adapted to sweeping changes in their economic, political, and cultural circumstances.5 Tremendous displacements have marked the experience of Dolpo’s communities within living memory: the assertion of Chinese authority over Tibet (and subsequent restrictions on the traffic of people, animals, and goods across its borders); the expansion of communications and transportation infrastructure in Nepal (which opened these remote villages to new goods and people, altering economics and crossing cultures); and the rise of modern nation-states like the People’s Republic of China and Nepal (with their attendant visions of development for their peripheral populations).

This is a case study of change. My goal is to communicate how these transformations have affected Dolpo, especially in relation to its production systems. Because these transformations have been played out (and are ongoing) throughout the borderlands of the Himalayas, Dolpo’s story is one with regional significance. Moreover, rangelands cover much of Nepal’s Himalayas and most of the neighboring Tibetan Plateau, and significant pastoral populations still depend on livestock to survive. Therefore, Dolpo’s experience vis-à-vis changing seasonal migrations and trade patterns, as well as livestock development and conservation schemes, may well bear valuable insights and lessons for those planning future interventions in these pastoral regions.6

Those interested in the cultural geography and historical ecology of the trans-Himalaya, as well as students and scholars of Tibet and the Himalayas, should find fertile material within this text for comparative studies. This work also adds to the literature that engages how pastoralists interact with states, especially as barter economies and open frontiers transform into capitalist markets and delineated borders (cf. Agrawal 1998; Chakravarty-Kaul 1998).

Several questions drive and structure this book: How have patterns of trade and seasonal migration changed in Dolpo (and the trans-Himalaya), particularly after the 1950s, when China reclaimed its erstwhile suzerainty over Tibet and closed its borders? With the emergence of the nation-state of Nepal, how did statutory and development interventions affect Dolpo? How have pastoralists in Dolpo adapted to shifting markets and resource availability? What are the economic prospects for sustaining pastoralism in this region of the Himalayas?

Figure 2 Detail map of Dolpo

An author’s background should be made explicit when asking questions like these. I have spent more than a decade living, working, and traveling in Asia, especially Nepal, where I lived between 1994 and 1997. When I first went to Dolpo in 1995, I found few accoutrements of the twentieth century—rapid communication, easy travel, packaged goods—to which we are so accustomed. Life seemed stripped bare there. A vast wind-filled landscape, higher and more expansive than any I had imagined, stretched out in mountain waves before me. I returned to Kathmandu with the germ of an idea and an appreciation for the forbidding challenges development initiatives would face in Dolpo.

I worked for two years as a consultant to the World Wildlife Fund Nepal Program (WWF-Nepal) in Kathmandu, and as such, participated in the practice and rhetoric of development. One of my primary responsibilities at WWF was to assist in helping to write grants for projects that integrated conservation and development. In 1996, as part of its larger package of assistance to Nepal’s western Karnali region, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) tendered a competitive proposal to conserve and develop Shey Phoksundo National Park, including parts of Dolpo. The project would be implemented over a period of six years in collaboration with Nepal’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC).

In the tense weeks leading up to the competition’s deadline, we at the WWF office worked feverishly to produce a project document that proposed to protect wildlife, enhance the effectiveness of national park staff, and improve local livelihoods. In its proposal, WWF sounded a note of alarm—a conservation crisis—in Shey Phoksundo National Park and decried the impacts of local people on natural resources, particularly faulting the inadequacy of their management practices. Yet this characterization gave me pause. How much did we actually know about resource management in Dolpo? Was there really a crisis? If so, what had produced these circumstances?

I had read hundreds of documents in which donors, governments, and organizations agreed—at least in theory—that local ecological knowledge and “scientific” resource management practices should be integrated. Everyone, it seemed, was calling for greater participation by local men and women in the design, management, and evaluation of protected areas. Yet resource management practices (which may be both hundreds of years old and in the midst of transition) do not readily reveal themselves through the modes of information gathering used by development workers—particularly Participatory Rural Appraisals (PRAs)—which are used to assess local conditions and plan projects.7 Common methodological problems in social science (e.g., how to represent and model communities) may be amplified in reports that give the impression of relevant planning information in the form of completed questionnaires. It takes more time than is often allotted by development agencies to gather detailed information about a community’s social institutions and livelihood practices, distinguish between types of information, and make judicious interpretations (cf. Duffield et al. 1998). Besides, knowledge may be kept and codified in ways that cannot be represented apart from practice.

During the summer of 1996, I was part of a team from WWF and the Department of National Parks that toured all of Shey Phoksundo National Park, which afforded me the opportunity to see much of Dolpo. This trip crystallized many of the questions I had about the gaps between ideas and the lived reality of Dolpo’s pastoralists. I began to develop and hone my research questions through my work at WWF, and yet I felt the need to test my own assumptions more explicitly against life in Dolpo’s villages and pastures.

To become an independent observer of Dolpo, I applied for and was granted a Fulbright fellowship in environmental studies in 1996. My Fulbright research asked several questions: How do Dolpo’s pastoralists manage rangelands and other natural resources? What institutions, both formal and informal, control these resources? Who has access to natural resources and how are these divided between and among communities? How do Dolpo’s villagers balance individual and community welfare? How have these practices and social institutions changed in living memory?

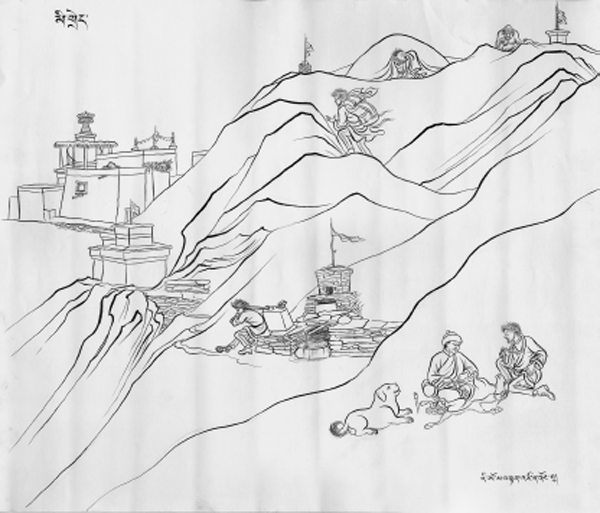

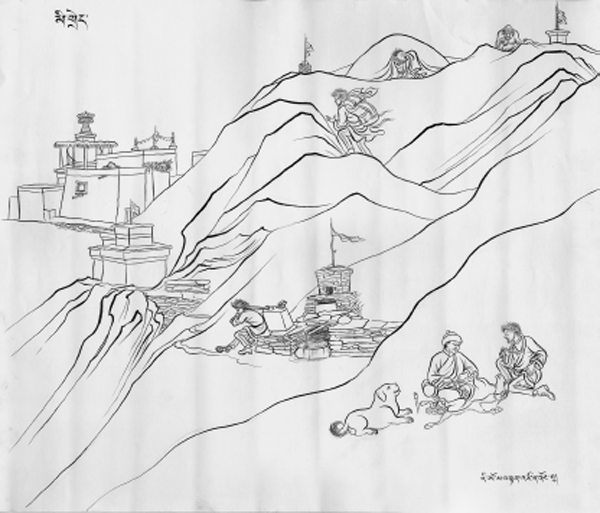

I began my Fulbright research in Kathmandu by meeting many Dolpo-pa*, who later became valuable local contacts.8 I watched the winter influx of migrants making their yearly pilgrimage to Nepal’s capital, a recent phenomenon in Dolpo’s lifeways. My sense of the geographical reach and economic patterns of this region expanded as I talked with Dolpo-pa about seasonal production cycles and their life of trade and movement. As it happened, I was also living in the same neighborhood of Kathmandu as Tenzin Norbu, a painter from the Panzang Valley of Dolpo. Norbu hails from a lineage of household monks (ngagpa) and artists. When I told him about my plans to go to Dolpo, Norbu suggested I live in his village, Tinkyu. He insisted that I should stay in his home, Tralung monastery. Though he was living in Kathmandu with his wife and children, Norbu’s mother and father were in the village, and he was sure that they would put me up. Norbu wrote a one-page letter to his parents asking them to help me.

So in fall of 1996, I set out for Dolpo laden with rice, dried fruit, peanut butter, chocolate, kerosene, serious cold weather gear, books, and questions: the essentials of any lengthy expedition. I was going to overwinter in a tiny village on the Tibetan border. The passes I crossed in November would be closed by snow once I reached my destination, the valley of Panzang. Those first months were an intense immersion period and consisted basically of observing and participating in the daily practices and rites of an agro-pastoral community in the trans-Himalaya.

Time passed simply. Those who remain in Dolpo for the winter pass their time in ways largely unaltered by Time. These days are measured in their pace, but always accompanied by diligent enterprise. Winter means community gatherings, mending, weaving, shoemaking, herding, collecting stores of fuel, gossiping, and drinking. Nights are deep and cold, days brilliant blues and earth-tone silhouettes. Stew of tsampa (roasted barley flour, the staple of Tibet) bookends the day, as the families gather around small and smoky hearths—the center of the house, the sole source of heat.

I lived in the household of Karma Tenzin (Norbu’s father), the head lama of Panzang Valley, and assimilated myself into its daily routine, performing simple chores such as sweeping the monastery, fetching water, and carding wool. I peeled a lot of potatoes and drank butter-salt tea. I spent hours studying my Tibetan language book and listening to the local dialect, which seemed planets apart.

Warmth and practicality dictated sartorial immersion, too, and I dressed in a warm woolen chubba, the weft of being Tibetan. My host mother, Yangtsum Lama, who taught me the daily rhythms of animal husbandry and showed me the compassion of a bodhisattva, had woven this particular cloak. On any given day, I could be found exploring the Panzang Valley, walking with shepherds, visiting the house of a friend, or sitting inside a monastery—icy stone fortresses with spare altars and disheveled libraries—as village lamas recited texts and renewed the religious rites of this place. Wherever I was, I was ever regaled with tea and barley beer, enveloped in Dolpo’s hospitality. Food varies little: tsampa, yak, and mutton, rice from the southern hills of Nepal, potatoes and radishes from the family’s fields. There is nary a vegetable in most meals, though wild nettles occasionally surface. We shared stories to the perpetual refrain of spindles dropping, spinning wool. No radio, one lantern, one foreigner—the cheekya—always asking questions, eyes tearing from the dense smoke of dung fires.

This work deals with a single population in qualitative terms, and provides a social portrait, but it is not an exhaustive ethnography. I used ethnographic techniques to study and understand features of Dolpo’s agro-pastoral system, but did not attempt an in-depth treatment of any specific rituals that constitute Dolpo’s social life. Typical ethnographic categories such as social structure and kinship, political hierarchies, material culture, and religious systems are not addressed in detail, and the possibilities for such work in Dolpo are wide-ranging.

Though a formal, household-by-household livestock and human census would certainly have generated interesting insights, I collected data like this only informally as numbers like these had always been used to tax locals in Dolpo and therefore generated mistrust. Instead, this book describes the historical and contemporary circumstances of Dolpo, and the factors that produced the patterns of movement, as well as allocations of time and resources, which we see there today (cf. Barth 1969; Helland 1980). The goal is to provide an account that is particular to Dolpo but grapples with wider political and economic forces.

A good way to understand pastoral life is by integrating its spatial and temporal patterns. To characterize rangeland management in Dolpo, I mapped areas of livestock use, herd movements, and pasture locations, and noted where livestock and wild ungulates overlapped. I examined grazing practices by asking about customary uses of natural resources and user rights within and between Dolpo’s villages and valleys. I learned about Dolpo’s natural history by gathering local names and uses for plant species and recorded herbalists’ and herders’ knowledge about local ecology.

My hosts moved with the seasons, driven by the ripening of the land, so I, too, migrated during my tenure as a researcher in Dolpo. In spring, after the long winter had broken, I traversed the Himalayas with Dolpo’s caravans to witness the ancient exchange of grain and salt. I sojourned for two months in the villages of Kag and Rimi (southwest Dolpa District), where Dolpo’s largest herds and their owners now pass the winter, in the lower altitude pastures of their Hindu trading partners. There, I observed an ongoing sociological experiment: the dynamic economic and social relationships that exist between two groups of traders—culturally Tibetan, Buddhist pastoralists and Hindu hill farmers. I interviewed both parties, asking about rates of exchange, resource access, pasture tenure, as well as the economic and cultural implications each felt while engaging in these relationships. The dramatic ecological shifts of the post-1959 period became evident when I hiked to the pastures above Kag-Rimi and watched Dolpo’s shepherds herd their yak, worn by winter and the constant movements demanded by a new set of migration patterns.9 Having spent a winter quietly listening to unfamiliar, difficult Tibetan, I had reentered the world of Nepali speakers (a language I felt far more comfortable with) and quickly accumulated data: oral accounts of the closing of the Tibetan border and the coming of the Nepal state, life histories, and other forms of remembering and interpreting Dolpo’s past.

Figure 3 Black-and-white ink drawing by Tenzin Norbu, humorously depicting how the author spent his time in Dolpo

During the spring of 1997, I joined the Dolpo-pa as they journeyed back home. I watched firsthand the interactions between this mobile, peripheral population and government officials as the caravans passed into Shey Phoksundo National Park. These exchanges occurred frequently over issues of resource access, like the harvesting of timber to build bridges and the depredation by snow leopards and wolves of Dolpo’s herds. I watched, too, as other visitors—trekkers, researchers, development consultants, and film crews—passed through the National Park and these remote valleys. The interactions of Dolpo’s villagers with outside actors were engrossing, and in this book I contemplate the processes of economic engagement, symbolic appropriation, cultural survival, and ecological adaptation. This story dwells less on loss amidst change in Dolpo, and forgoes nostalgia to tell of local creativity and tenacity.

I visited Dolpo during the summer—the peak season for dairy production—several times. Summer is Dolpo at its bucolic best. At the high pastures, black, yak-hair tents dot the landscape, tucked beneath snowy peaks melting milky glacier water. The air loses its winter edge and invites laughter, as herdsmen admire the newborn yak romping playfully and waving bushy tails, trying out their newfound strength. Wildflowers crop up and give the fleeting illusion of abundance. Moisture from snowmelt and monsoon rains provides for a flush of vegetation growth, and rapid weight gain for the animals.

During the course of my research, I observed local Dolpo villagers in many contexts: during herding, informal gatherings, religious rituals, and formal village assemblies. I joined shepherds (mostly children and women) as they passed laborious days herding animals and collecting dung and shrubs for fuel in this land without trees. I scrutinized the social context of resource management, and how tradition, power, and politics play out in small-scale communities like Dolpo’s. I familiarized myself with local labor and household production arrangements, and tried to understand the values and the ends Dolpo-pa pursued as land managers. This book is an attempt to convey the structure and sense of human ecology in this part of the Himalayas.

I met hundreds of men, women, and children from Dolpo—my key informants—while researching this book (1995–2002). I gathered information in a variety of ways, ranging from informal meetings along a trail to structured interviews and more formal discussions in groups. Among my informants were religious lineage holders (lamas and householder priests), local headmen, medical practitioners, and members of political establishments at the local and national levels. Alongside my fieldwork in Dolpo, I interviewed anyone who had spent time there, and read their written work.

To understand the objectives and policies of the Nepal state, I conducted interviews with officers of His Majesty’s Government of Nepal in Kathmandu and Dunai, especially members of the Department of Livestock Services (Ministry of Agriculture) and the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation). Over the course of several years, I conducted interviews with many staff of Shey Phoksundo National Park, as well as field-workers from nongovernmental organizations such as USAID, DANIDA, SNV, UNDP, WWF-US, and the WWF Nepal Program.

The story I pursued in Dolpo evolved both in content and scope after my sojourn in Nepal. I matriculated at the University of California-Berkeley to earn a master’s in rangeland management and wrote my thesis about Dolpo. This book draws on that earlier manuscript and borrows concepts from ecology. As a result, I employ some functional explanations to analyze environmental adaptations in Dolpo, but I also draw heavily on anthropological and symbolic interpretations to understand what I observed there. I offer the following précis as a map to this book.

PRÉCIS

While its configuration of environment, culture, and historical circumstances are particular, Dolpo’s pastoral system shares certain elemental characteristics with other pastoral communities. Throughout this text, I test and draw from the literature on pastoralism to examine how Dolpo’s system fits in, and to provide some perspective on the transformation of pastoral systems along the Indo-Tibetan frontier. Would these academic models have anticipated the outcomes of the past fifty years in Dolpo?

Melvyn Goldstein (1975) uses the term agro-pastoralism to denote the subsistence modes of northwestern Nepal, in which both animal husbandry and agriculture play major roles in economic and cultural life. While agriculture, animal husbandry, and trade are tightly integrated and overlap seasonally in Dolpo, for clarity I discuss them separately in chapters 1 and 2. Later, when I describe how Dolpo’s agro-pastoralists adapted to the loss of winter pastures in Tibet, it becomes clear how these livelihood strategies are, in fact, in lockstep. Indeed, the first two chapters of this book are its most ethnographic and deal with the triangulated production system of agriculture, animal husbandry, and trade. Though by no means exhaustive, these chapters explicate how resources are used in a marginal and risky environment and draw out the inner logic of Dolpo’s land managers.

Chapter 1 depicts Dolpo’s physical environment and climate, focusing on the high rangelands of the trans-Himalaya. Agricultural production at these high altitudes provides Dolpo villagers less than six months’ supply of food. I give a brief picture of agriculture, the keystone to food security, and local farmers’ practices, as well as their community labor and property arrangements. Animals contribute to every aspect of economic production, including agriculture. I explain animal husbandry practices in Dolpo such as herd composition, breeding, dairy production, livestock nutrition, and the relationships between religion and livestock. Trade is the second element of Dolpo’s subsistence triad. Chapter 1 describes the historical trade patterns between Tibet and Nepal—in which Dolpo played a regional role—as well as the economic and social relationships that controlled and facilitated this commerce across the Himalayas.

Chapter 2 delves into Dolpo’s pastoral production system at the scales of communities and households. Dolpo-pa have developed sophisticated social arrangements that organize resource use and livestock management, as well as coordinate trade and migration patterns, to thrive in such a marginal environment. I describe the seasonal migrations of Dolpo’s four valleys and consider how critical decisions in regard to resource use are made. Resource-use practices represent a wide array of practical skills and acquired intelligence in responding to a constantly changing natural and human environment (Scott 1998). Resource use is also embedded in cultural practices. Thus, some of the social and religious rituals that accompany and often initiate agricultural, pastoral, and trade activities are illustrated.

Chapter 3, 4, and 5 are historical and political in nature. These chapters piece together a meta-narrative of political events and economic trends that transpired in Nepal and China after 1950. Chapter 3 presents a selected history of Dolpo—a broad swath across time, from approximately 650 to 1950—to place its contemporary story into a chronological context and regional setting. What were the early political and economic relationships between Dolpo and its neighbors? How did relations between Nepal, Tibet, India, and China change over the centuries and how did this affect Dolpo, especially in terms of trans-border trade and pastoral migration? To answer these questions, I researched historical trade and economic relations across the Indo-Tibetan frontier and focus here on critical events in Tibet and Nepal that shaped Dolpo’s modern history. Dolpo is a lens unto the second half of the twentieth century and the transformations to which pastoral communities of the trans-Himalaya have adapted.

In chapters 4 and 5, I survey the post-1950 period, focusing on the nation-state building programs pursued by China in Tibet and by Nepal in its northern, culturally Tibetan regions. These parallel chapters show some of the development initiatives pursued by these states and trace the interactions of Nepal and China with their peripheral, pastoral populations. In chapter 4, I narrate how, after 1951, the Chinese secured control over the Tibetan population by monopolizing transport and infrastructure, placing a preponderance of military force on the Tibetan Plateau. This chapter charts the trade and pastoral policies of the Communist Party and the administration of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), with specific reference to nomads in western Tibet, to read the transformations that occurred across the border in Dolpo. I quickly sketch the tumultuous politics of the Communist Party and the subsequent upheavals that all of China passed through, especially the Great Leap Forward, communes, and the Cultural Revolution. Though I have been to Tibet several times, I have not traveled in the west, the region immediately north of Dolpo. Thus, I rely heavily on the works of Melvyn Goldstein, Cynthia Beall, Robert Ekvall, Tsering Shakya, and others for information on developments in western Tibet after 1950.10

The political relations between India, China, and Nepal are also a focus of chapters 4 and 5. The narrative is drawn to moments of crisis and decision such as the 1962 Sino-Indian conflict and the signing of border agreements between these nations during the early 1960s. The closing of the Indo-Tibetan frontier and the creation of modern borders delineated and transformed the spaces that pastoralists inhabited and depended upon for survival. Concentrating on trade, animals, and rangeland resources, I consider the interactions of peripheral groups in border areas with the processes of state formation and boundary making along a contested geopolitical frontier (cf. Agrawal 1998).

These chapters also tell, in brief, the tale of the Tibetan resistance movement, and how the Indo-Tibetan frontier became a border. Though the neighboring Mustang region was the chief base for this guerrilla army, Dolpo was implicated—by geography and shared cultural roots—in the activities of the Tibetan fighters, which strongly affected the relations of northern regions like Dolpo and Mustang with the Nepali state. For example, the presence of a foreign rebel army in these northern districts was the primary reason that the king of Nepal declared these areas restricted, which limited the access of visitors to Dolpo until the 1990s.

Chapter 6 shifts from a regional and historical meta-narrative back to Dolpo, chronicling how villagers there adapted their trade patterns and pastoral migrations after 1959. Chapter 6 discusses the rapid and unprecedented changes subsequent to the closing of the Tibetan border, which forced Dolpo’s pastoralists to seek alternative winter pastures and rework their trade-based economy. The influx of Tibetan refugees and their animals into Dolpo during the early 1960s precipitated a rangeland crisis, with hundreds of livestock dying of starvation and the productive base of Dolpo’s economic systems drastically diminished by overgrazing. Forced to reconstruct both their seasonal movements and economic cycles, the people of Dolpo renegotiated their livelihood practices in a radically different political, cultural, and ecological landscape.

In chapter 6, I give an overview of livestock production and trade patterns and show variations in herd management strategies, social organization, land tenure, and migrations between and among the four valleys, teasing out the complexity of Dolpo’s agro-pastoral system. In this chapter, I also detail the ways that the salt-grain trade in which Dolpo villagers have participated for centuries, as well as the commerce in livestock and other commodities, was radically altered after 1959. I turn my attention specifically to the ways in which the commercial and social relationships that sustained these interactions have both changed and persisted. I write about the emergence of a market economy and the expansion of transportation infrastructure in Nepal and the Tibet Autonomous Region. I also show how the incursion of Indian salt into rural Nepal, a steady erosion in the value of Tibetan salt, and changing rules governing the use of pastures and forests continue to transform Dolpo’s way of life.

Chapter 7 traces the evolution of conservation concepts in Nepal and the creation in the 1980s of Shey Phoksundo National Park in Dolpa District. Dolpo’s encounter with tourists and Western-style development is discussed, particularly in light of the attitudes and methodologies adopted by these agents of change, and I highlight key park-versus-people issues: livestock depredation by wildlife, hunting, trade in medicinal plant species, and the impact of army troops on local resources.

Chapter 7 summarizes the conservation and development interventions undertaken by the government of Nepal, international aid agencies, and nongovernmental organizations in Dolpo since the 1960s. How have these affected patterns of resource use and relations between the state and local people in Dolpo? This chapter also presents a critical review of the government’s livestock development efforts—programs in range reseeding, livestock breeding, and veterinary clinics—that were tried in Dolpo. I make the case that the government’s policies and disposition toward local people has undermined the efficacy of livestock development, and I insert Dolpo into the ongoing debates about the applicability of Western range management techniques to pastoral areas. Specifically, the feasibility of managing a dynamic, nonequilibrium ecosystem like Dolpo’s by using the “carrying capacity” approach is challenged.

Chapter 8 focuses on the making of the feature film Himalaya (aka Caravan) in Dolpo.11 Shot on-location with mostly local actors, Himalaya thrust this once obscure border area into the global arena. Based on lengthy interviews, media accounts, and personal observations in Dolpo, I relate the film’s short and long-term consequences for the people of Dolpo. I cast this movie against the background of the popular phenomenon of Tibet, and explore how and why certain representations of Tibet and “Tibetanness” are perpetuated in popular media. I argue that the images of Dolpo and Tibet that this film projects are both inaccurate and disingenuous, and that these representations speak more to the motives and means of their makers than to the realities of life in Dolpo.

The book’s final chapter provides glimpses of Dolpo today, and opens possible windows onto its future. What are the forces determining the continuing viability of Dolpo’s pastoral and trade economy? How is the People’s War (initiated by the Communist Party of Nepal—Maoist), which began in 1996 as I set off to do my fieldwork, affecting Dolpo?

I am preceded in Dolpo by many, and was initially drawn to this region, like them, because of its sheer isolation and ruggedness. Ekai Kawaguchi, a Japanese monk, visited Dolpo enroute to Tibet in 1903 and mentioned the area in his memoirs, Three Years in Tibet (1909). In the 1950s, Giusseppe Tucci, an Italian Tibetologist and art historian, and Toni Hagen, a Swiss geographer and early proponent of infrastructure development in Nepal, traveled through Dolpo as part of their marathon journeys across the Himalayas. During the 1960s, Corneille Jest, David Snellgrove, and Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf, along with their enduring Nepali companions, studied Dolpo’s material and religious culture. Jest’s Dolpo: Communautés de Langue Tibétaine du Nepal and Snellgrove’s Four Lamas of Dolpo and Himalayan Pilgrimage remain seminal works in the limited literature on Dolpo.12 John Smart and John Wehrheim (1977:50) made a brief survey of the region and wrote that Dolpo was “a last manifestation of traditional country life, the grassroots of Tibetan culture.”

Botanists such as T. B. Shrestha, along with Oleg Polunin and Adam Stainton, provided early reports of the area’s flora. The ornithologists Flemings (Robert senior and junior), George Schaller (Wildlife Conservation Society), who surveyed the area’s fauna for the New York Zoological Society, along with naturalist Karna Sakya and biologists John Blower and Per Wegge, raised awareness of Dolpo and helped convince the Nepali government to create Shey Phoksundo, the country’s largest national park (cf. Blower 1972; Sakya 1978; Schaller 1977; Polunin and Stainton 1984).

Perhaps the best-known account of Dolpo is Peter Matthiessen’s The Snow Leopard, a travelogue of his trek with Dr. Schaller in search of the elusive snow leopard. The Snow Leopard became a classic—standard reading fare for generations of explorers and trekkers in Nepal. More an inward journey than a detailed description of Dolpo, Matthiessen nevertheless focused Western attention on the region.

During the 1980s and 1990s, French photographer Eric Valli chronicled the area extensively and published two books with Diane Summers—Dolpo: The Hidden Land of the Himalayas (1987) and Caravans of the Himalaya (1994)—as well as numerous magazine articles. Anthropologists Nicolas Sihlé and Marietta Kind have both conducted in-depth research into religious symbolism, rituals, and lineages in both Buddhist and Bön traditions of the Tarap and Phoksumdo Valleys, respectively (cf. Sihlé 2000; Kind 2002b). Other published works on Dolpo are scant and consist mostly of government reports written on the basis of brief surveys.

I explicitly engage regional studies of the Himalayas in this book. During the 1970s, Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf traversed the Himalayas and observed many of the important transitions that were occurring during this time, while Melvyn Goldstein conducted pioneering studies with the Mugali pastoralists of Humla District; Goldstein and Beall’s later research with nomads in Tibet and Mongolia also provided a valuable regional perspective. In the 1980s, Barry Bishop and Hanna Rauber completed studies of socioeconomic change among ethnically Tibetan agro-pastoralists in Humla District. Several important studies from other regions of Nepal provided important comparative perspectives: James Fisher’s (1986) work in the Tichurong area of southern Dolpa District; Stan Stevens’s (1993) account of resource management among the Sherpa; Nancy Levine’s (1987) discussion of caste, state, and ethnic boundaries in Nepal; and the publications of rangeland ecologists Daniel Miller and Camille Richard.

The following regional studies proved especially helpful in spurring my thinking about Dolpo: Arun Agrawal’s (1998), Minoti Chakravarty-Kaul’s (1998), and Vasant Saberwal’s (1996) work on pastoralists in the Indian Himalayas; Wim van Spengen’s (2000) treatment of the Nyishangba of Manang District, Nepal; and Barbara Aziz’s (1978) ethnography of agropastoral communities in the Tingri region of central Tibet. These, and other works, helped frame this book.

It is my hope that the present volume will aid in understanding the consequences of actions and decisions taken during these past fifty years and help reduce the margin of error in the future by showing what is viable—economically, ecologically, and culturally—in places like Dolpo (cf. Popper 1972; Helland 1980). Barbara Aziz (1978: x) wrote, “Research must distil from the raconteur the most meaningful things in a life and excite into recall, details and persons forgotten long ago.” This book is successful if it conveys even a small measure of the meaningful things I learned from the people of Dolpo.