Chapter 5

Performing calculations in pivot tables

In this chapter, you will:

Introducing calculated fields and calculated items

When analyzing data with pivot tables, you will often need to expand your analysis to include data based on calculations that are not in your original data set. Excel provides a way to perform calculations within a pivot table through calculated fields, measures, and calculated items.

A calculated field is a data field you create by executing a calculation against existing fields in the pivot table. Think of a calculated field as a virtual column added to your data set. This column takes up no space in your source data, contains the data you define with a formula, and interacts with your pivot data as a field—just like all the other fields in your pivot table.

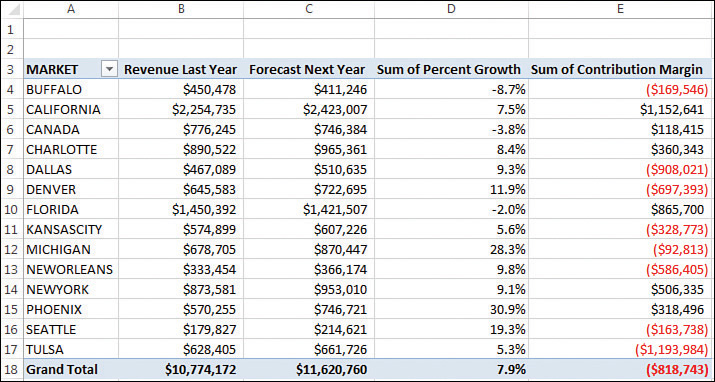

A measure is a calculated field created in a Data Model pivot table using the Data Analysis Expressions (DAX) formula language. In many cases, measures run circles around calculated fields. In order to create a measure, you have to choose “Add This Data To The Data Model” when creating the pivot table. Measures are discussed in length in Chapter 10, “Unlocking features with the Data Model and Power Pivot.” Refer to “Creating Median in a pivot table using DAX measures,” “Reporting text in the Values area,” and “Using time intelligence,” in Chapter 10. Measures are also used in the case study at the end of this chapter: “Case study: Using DAX measures instead of calculated fields.”

A calculated item is a data item you create by executing a calculation against existing items within a data field. Think of a calculated item as a virtual row of data added to your data set. This virtual row takes up no space in your source data and contains summarized values based on calculations performed on other rows in the same field. Calculated items interact with your pivot data as data items—just like all the other items in your pivot table.

With calculated fields and calculated items, you can insert a formula into a pivot table to create your own custom field or data item. Your newly created data becomes a part of your pivot table, interacting with other pivot data, recalculating when you refresh, and supplying you with a calculated metric that does not exist in your source data.

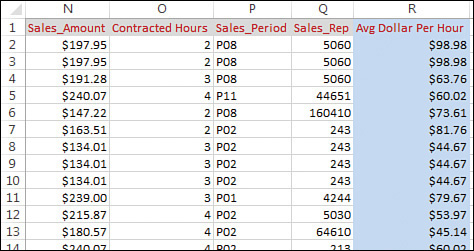

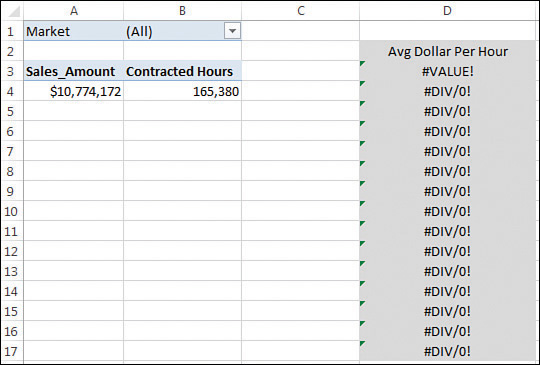

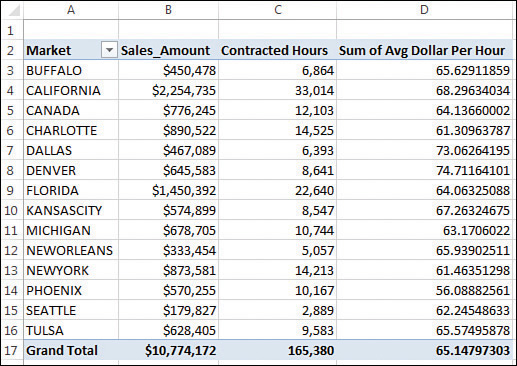

The example in Figure 5-1 demonstrates how a basic calculated field can add another perspective on your data. Your pivot table shows total sales amount and contracted hours for each market. A calculated field that shows your average dollar per hour enhances this analysis and adds another dimension to your data.

Now, you might look at Figure 5-1 and ask, “Why go through all the trouble of creating calculated fields or calculated items? Why not just use formulas in surrounding cells or even add the calculation directly into the source table to get the information needed?”

To answer these questions, in the next sections, we will look at the three different methods you can use to create the calculated field in Figure 5-1:

Manually add the calculated field to your data source.

Use a formula outside your pivot table to create the calculated field.

Insert a calculated field directly into your pivot table.

Method 1: Manually add a calculated field to the data source

If you manually add a calculated field to your data source, the pivot table can pick up the field as a regular data field (see Figure 5-2). On the surface, this option looks simple, but this method of precalculating metrics and incorporating them into your data source is impractical on several levels.

If the definitions of your calculated fields change, you have to go back to the data source, recalculate the metric for each row, and refresh your pivot table. If you have to add a metric, you have to go back to the data source, add a new calculated field, and then change the range of your pivot table to capture the new field.

Method 2: Use a formula outside a pivot table to create a calculated field

You can add a calculated field by performing the calculation in an external cell with a formula. In the example shown in Figure 5-3, the Avg Dollar per Hour column was created with formulas referencing the pivot table.

Although this method gives you a calculated field that updates when your pivot table is refreshed, any changes in the structure of your pivot table have the potential of rendering your formula useless.

As you can see in Figure 5-4, moving the Market field to the Filters area changes the structure of your pivot table—and exposes the weakness of makeshift calculated fields that use external formulas.

Method 3: Insert a calculated field directly into a pivot table

Inserting a calculated field directly into a pivot table is the best option. Going this route eliminates the need to manage formulas, provides for scalability when your data source grows or changes, and allows for flexibility in the event that your metric definitions change.

Another huge advantage of this method is that you can alter your pivot table’s structure and even measure different data fields against your calculated field without worrying about errors in your formulas or losing cell references.

The pivot table report shown in Figure 5-5 is the same one you see in Figure 5-1, except it has been restructured to show the average dollar per hour by market and product.

The bottom line is that there are significant benefits to integrating your custom calculations into a pivot table, including the following:

Elimination of potential formula and cell reference errors.

Ability to add or remove data from your pivot table without affecting your calculations.

Ability to auto-recalculate when your pivot table is changed or refreshed.

Flexibility to change calculations easily when your metric definitions change.

Ability to manage and maintain your calculations effectively.

Note

Note

If you move your data to PowerPivot, you can use the DAX formula language to create more powerful calculations. See Chapter 10, “Unlocking features with the Data Model and Power Pivot,” to get a concise look at the DAX formula language.

Creating a calculated field

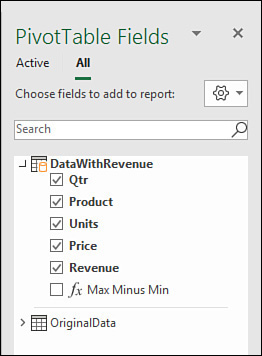

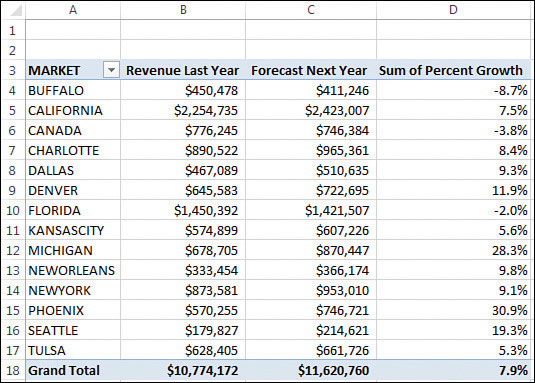

Before you create a calculated field, you must first have a pivot table, so build the pivot table shown in Figure 5-6.

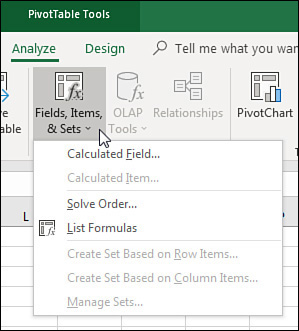

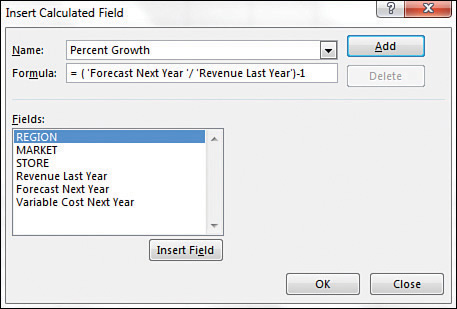

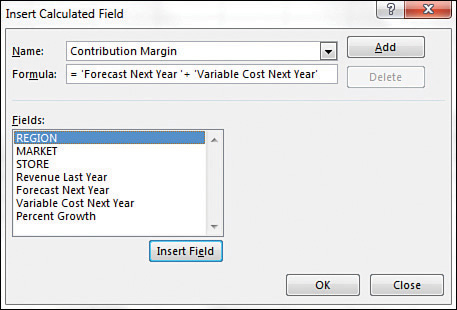

Once you have a pivot table, it’s time to create your first calculated field. To do this, you must activate the Insert Calculated Field dialog box. Select Analyze under the PivotTable Tools tab and then select Fields, Items, & Sets from the Calculations group. Selecting this option activates a drop-down menu from which you can select Calculated Field, as demonstrated in Figure 5-7.

Note

Note

Normally, the fields in the Values area of Figure 5-6 would be called Sum Of Sales_Amount and Sum Of Contracted Hours. After creating the default pivot table, click in cell B2 and type a new name of Sales_Amount followed by a space. In a similar fashion, rename C2 from Sum Of Contracted Hours to Contracted Hours followed by a space.

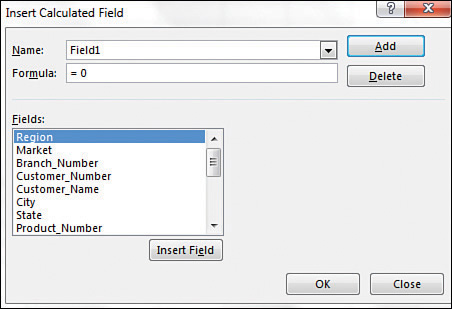

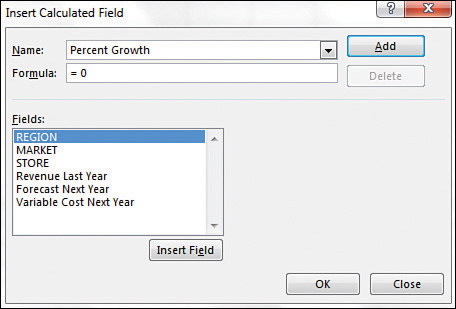

After you select Calculated Field, Excel activates the Insert Calculated Field dialog box, as shown in Figure 5-8.

Notice the two input boxes, Name and Formula, at the top of the dialog box. The objective here is to give your calculated field a name and then build the formula by selecting the combination of data fields and mathematical operators that provide the metric you are looking for.

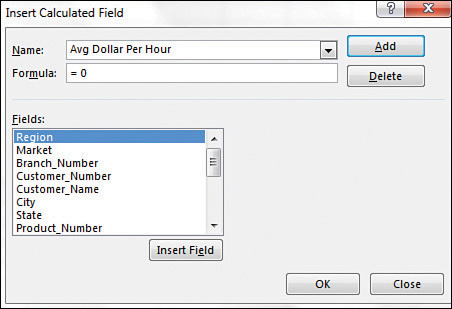

As you can see in Figure 5-9, you first give your calculated field a descriptive name—that is, a name that describes the utility of the mathematical operation. In this case, enter Avg Dollar Per Hour in the Name input box.

Next, go to the Fields list and double-click the Sales_Amount field. Enter / to let Excel know you plan to divide the Sales_Amount field by something.

Caution

Caution

By default, the Formula input box in the Insert Calculated Field dialog box contains = 0. Ensure that you delete the zero before continuing with your formula.

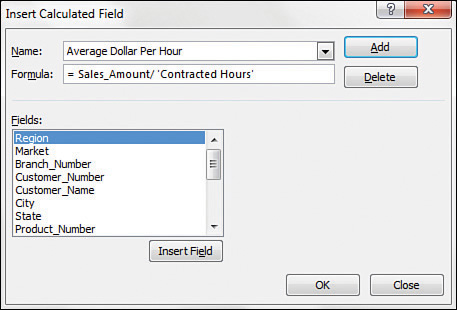

At this point, your dialog box should look similar to the one shown in Figure 5-10.

Next, double-click the Contracted Hours field to finish your formula, as illustrated in Figure 5-11.

Finally, select Add and then click OK to create the new calculated field.

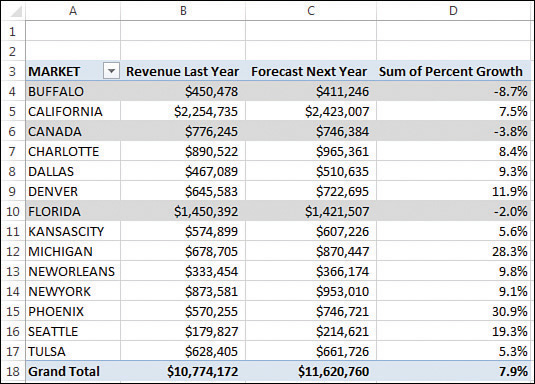

As you can see in Figure 5-12, the pivot table creates a new field called Sum Of Avg Dollar Per Hour. Note that in addition to adding your calculated field to the pivot table, Excel also adds your new field to the PivotTable Fields list.

Note

Note

The resulting values from a calculated field are not formatted. You can easily apply any desired formatting by using some of the techniques from Chapter 3, “Customizing a pivot table.”

Does this mean you have just added a column to your data source? The answer is no.

Calculated fields are similar to the pivot table’s default subtotal and grand total calculations in that they are all mathematical functions that recalculate when the pivot table changes or is refreshed. Calculated fields merely mimic the hard fields in your data source; you can drag them, change field settings, and use them with other calculated fields.

Take a moment and take another close look at Figure 5-11. Notice that the formula entered there is in a format similar to the one used in the standard Excel formula bar. The obvious difference is that instead of using hard numbers or cell references, you are referencing pivot data fields to define the arguments used in this calculation. If you have worked with formulas in Excel before, you will quickly grasp the concept of creating calculated fields.

Creating a calculated item

As you learned at the beginning of this chapter, a calculated item is a virtual data item you create by executing a calculation against existing items within a data field. Calculated items come in especially handy when you need to group and aggregate a set of data items.

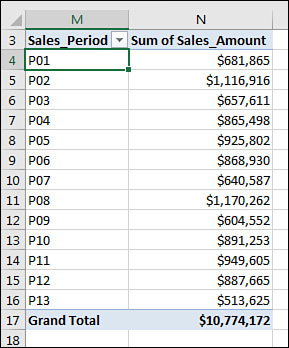

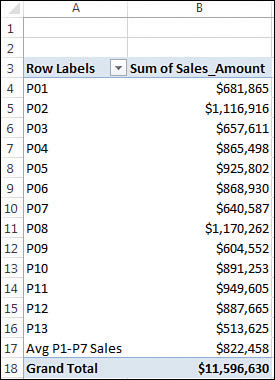

For example, the pivot table in Figure 5-20 gives you sales amount by sales period. Imagine that you need to compare the average performance of the most recent six sales periods to the average of the prior seven periods. That is, you want to take the average of P01–P07 and compare it to the average of P08–P13.

Note

Note

Watch the Grand Total amount through the next several examples. The $10.77 million shown in Figure 5-20 is the correct amount.

Caution

Caution

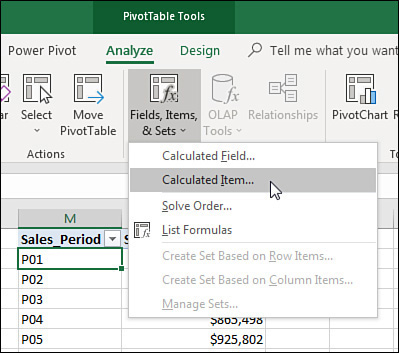

Calculated Items are always added to one specific field in the pivot table. In this case, you are calculating new totals along the Sales_Period field. Thus, you must select one of the Sales_Period cells before selecting Calculated Item from the Fields Items and Sets drop-down menu.

Place your cursor on any data item in the Sales_Period field, and then select Fields, Items, & Sets from the Calculations group. Next, select Calculated Item, as shown in Figure 5-21.

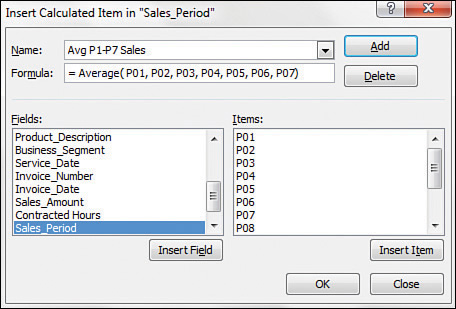

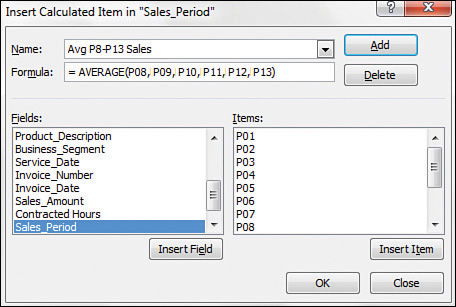

Selecting this option opens the Insert Calculated Item dialog box. A quick glance at Figure 5-22 shows you that the top of the dialog box identifies which field you are working with. In this case, it is the Sales_Period field. In addition, notice that the Items list box is automatically filled with all the items in the Sales_Period field.

You need to give your calculated item a name and then build its formula by selecting the combination of data items and operators that provide the metric you are looking for.

In this example, name your first calculated item Avg P1-P7 Sales, as shown in Figure 5-23.

Next, you can build your formula in the Formula input box by selecting the appropriate data items from the Items list. In this scenario, you want to create the following formula:

=Average(P01, P02, P03, P04, P05, P06, P07)

Enter the formula shown in Figure 5-23 into the Formula input box.

Click OK to activate your new calculated item. As you can see in Figure 5-24, you now have a data item called Avg P1-P7 Sales.

You can use any worksheet function in both a calculated field and a calculated item. The only restriction is that the function you use cannot reference external cells or named ranges. In effect, this means you can use any worksheet function that does not require cell references or defined names to work (such as COUNT, AVERAGE, IF, and OR).

Create a calculated item to represent the average sales for P08–P13, as shown in Figure 5-25.

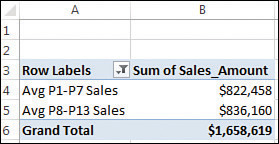

Now you can hide the individual sales periods so that the report shows only the two calculated items. As shown in Figure 5-26, after a little formatting, your calculated items allow you to compare the average performance of the six most recent sales periods to the average of the prior seven periods.

Caution

Caution

It is often prudent to hide the data items you used to create your calculated item. In Figure 5-26, notice that all periods have been hidden. This prevents any grand totals and subtotals from showing incorrect aggregations. One could argue that the sum of two averages shown in the Grand Total row is meaningless. Remove the Grand Total by using PivotTable Tools | Design, Grand Totals, Off For Rows And Columns.

Understanding the rules and shortcomings of pivot table calculations

There is no better way to integrate your calculations into a pivot table than by using calculated fields and calculated items. However, calculated fields and calculated items do come with their own set of drawbacks. It’s important you understand what goes on behind the scenes when you use pivot table calculations, and it’s even more important to be aware of the boundaries and limitations of calculated fields and calculated items to avoid potential errors in your data analysis.

The following sections highlight the rules related to calculated fields and calculated items that you will most likely encounter when working with pivot table calculations.

Remembering the order of operator precedence

Just as in a spreadsheet, you can use any operator in your calculation formulas—meaning any symbol that represents a calculation to perform (+, -, *, /, %, ^). Moreover, just as in a spreadsheet, calculations in a pivot table follow the order of operator precedence. In other words, when you perform a calculation that combines several operators, as in (2+3) * 4/50%, Excel evaluates and performs the calculation in a specific order. The order of operations for Excel is as follows:

Evaluate items in parentheses.

Evaluate ranges (:).

Evaluate intersections (spaces).

Evaluate unions (,).

Perform negation (–).

Convert percentages (%).

Perform exponentiation (^).

Perform multiplication (*) and division (/), which are of equal precedence.

Perform addition (+) and subtraction (–), which are of equal precedence.

Evaluate text operators (&).

Perform comparisons (=, <>, <=, >=).

Note

Note

Operations that are equal in precedence are performed left to right.

Consider this basic example. The correct answer to (2+3)*4 is 20. However, if you leave off the parentheses, so that you have 2+3*4, Excel performs the calculation like this: 3*4 = 12 + 2 = 14. The order of operator precedence mandates that Excel perform multiplication before addition. Entering 2+3*4 gives you the wrong answer. Because Excel evaluates and performs all calculations in parentheses first, placing 2+3 inside parentheses ensures the correct answer.

Here is another widely demonstrated example. If you enter 10^2, which represents the exponent 10 to the second power as a formula, Excel returns 100 as the answer. If you enter –10^2, you expect –100 to be the result, but instead Excel returns 100 yet again. The reason is that Excel performs negation before exponentiation, which means Excel converts 10 to –10 before doing the exponentiation, effectively calculating –10*–10, which indeed equals 100. When you use parentheses in the formula, –(10^2), Excel calculates the exponent before negating the answer, giving you –100.

Understanding the order of operations helps you avoid miscalculating your data.

Using cell references and named ranges

When you create calculations in a pivot table, you are essentially working in a vacuum. The only data available to you is the data that exists in the pivot cache. Therefore, you cannot reach outside the confines of the pivot cache to reference cells or named ranges in your formula.

Using worksheet functions

When you build calculated fields or calculated items, Excel enables you to use any worksheet function that accepts numeric values as arguments and returns numeric values as the result. Some of the many functions that fall into this category are COUNT, AVERAGE, IF, AND, NOT, and OR.

Some examples of functions you cannot use are VLOOKUP, INDEX, SUMIF, COUNTIF, LEFT, and RIGHT. Again, these are all impossible to use because they either require cell array references or return textual values as the result.

Using constants

You can use any constant in your pivot table calculations. Constants are static values that do not change. For example, in the formula [Units Sold]*5, 5 is a constant. Though the value of Units Sold might change based on the available data, 5 always has the same value.

Referencing totals

Your calculation formulas cannot reference a pivot table’s subtotals or grand total. This means that you cannot use the result of a subtotal or grand total as a variable or an argument in a calculated field. Measures created using the DAX formula language can overcome this limitation.

Rules specific to calculated fields

Calculated fields will not work in all cases. There are times when it is better to add the intermediate calculation to the original data set.

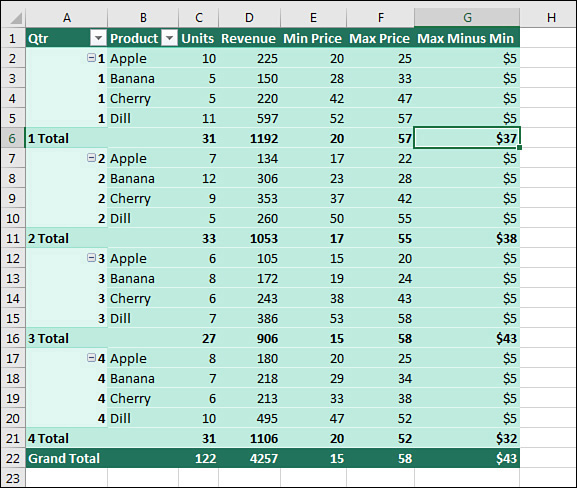

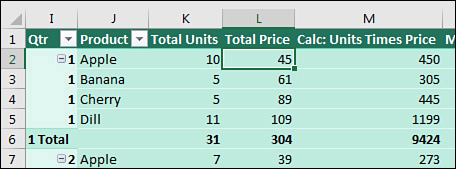

Consider the very simple data set shown in Figure 5-27. You had two sales of apples in Q1. The first was five cases at $20 and then five cases at $25. The total Q1 sales should be $225 derived by calculating =SUM(5*20,5*25).

The pivot table will get this calculation wrong on several levels. Cell L2 in Figure 5-28 adds the two unit prices together, producing a meaningless answer of $45. The calculated field in M2 then takes the correct total of 10 cases of apples times the incorrect price of $45 to arrive at $450 as the total Q1 revenue for apples. Recall that the correct answer from Figure 5-27 should have been $225. The problem gets worse at the Q1 total of $9,424 versus a correct answer of $1,192. At the Grand Total level, the pivot table is showing $137,372 versus a correct answer of $4,257.

Based on the example in Figure 5-28, you would think that the rule is that pivot tables are summing first and then the calculated field is multiplying the summary numbers. But this is not always true.

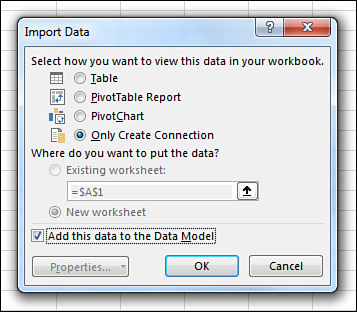

Based on Figure 5-28, the rule seems to be that the pivot table will perform the aggregation first and then use the formulas in the Calculated Field. However, look at a different example from the same data set. Your manager wants to know the lowest price for apples, the highest price for apples, and the difference between those.

Drag Price to the Values area two more times. Double-click the heading in N1 and change the calculation to Minimum. Double-click the heading in O1 and change the calculation to Maximum. The numbers in columns N and O are correct.

But then add a calculated field with MAX(Price) - MIN(Price), as shown in Figure 5-29. If Excel is doing the aggregation first, the answer to this formula should be 25–20 or 5. But the answer is zero. This indicates that Excel is reaching back and doing this math: =SUM(MAX(D2)-MIN(D2),MAX(D3)-MIN(D3)). Why does the calculation engine change methods? If you worked in Redmond on the Excel team, you could do some Excel archeology in the code base to figure it out, but the easier method is to switch from calculated fields to measures, as described in the following case study.

Rules specific to calculated items

To use calculated items effectively, it is important that you understand a few ground rules:

You cannot use calculated items in a pivot table that uses averages, standard deviations, or variances. Conversely, you cannot use averages, standard deviations, or variances in a pivot table that contains a calculated item.

You cannot use a page field to create a calculated item, nor can you move any calculated item to the report filter area.

You cannot add a calculated item to a report that has a grouped field, nor can you group any field in a pivot table that contains a calculated item.

When building your calculated item formula, you cannot reference items from a field other than the one you are working with.

As you think about the pages you have just read, don’t be put off by these shortcomings of pivot tables. Despite the clear limitations highlighted, the capability to create custom calculations directly into your pivot table remains a powerful and practical feature that can enhance your data analysis.

Now that you are aware of the inner workings of pivot table calculations and understand the limitations of calculated fields and items, you can avoid the pitfalls and use these features with confidence.

Managing and maintaining pivot table calculations

In your dealings with pivot tables, you will find that sometimes you don’t keep a pivot table for more than the time it takes to say, “Copy, Paste Values.” Other times, however, it will be more cost-effective to keep a pivot table and all its functionality intact.

When you find yourself maintaining and managing pivot tables through changing requirements and growing data, you might find the need to maintain and manage your calculated fields and calculated items as well.

Editing and deleting pivot table calculations

When a calculation’s parameters change, or you no longer need a calculated field or calculated item, you can activate the appropriate dialog box to edit or remove the calculation.

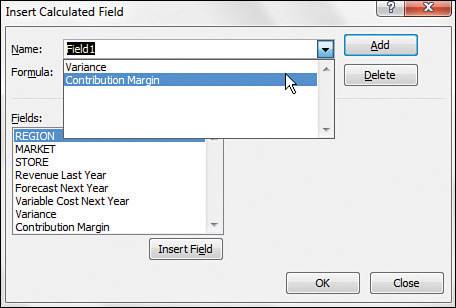

Simply activate the Insert Calculated Field or Insert Calculated Item dialog box, and select the Name drop-down menu, as demonstrated in Figure 5-36.

As you can see in Figure 5-37, after you select a calculated field or item, you have the option of deleting the calculation or modifying the formula.

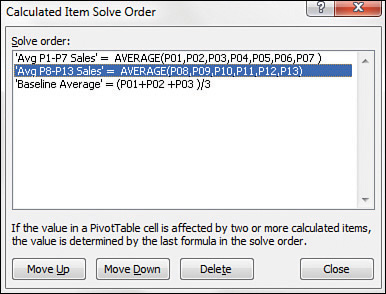

Changing the solve order of calculated items

If the value of a cell in your pivot table is dependent on the results of two or more calculated items, you have the option of changing the solve order of the calculated items. That is, you can specify the order in which the individual calculations are performed.

To specify the order of calculations, you need the Solve Order dialog box. To get there, place your cursor anywhere in the pivot table, select Fields, Items, & Sets from the Calculations group, and then select Solve Order.

The Solve Order dialog box, shown in Figure 5-38, lists all the calculated items that currently exist in the pivot table. The order in which the formulas are listed here is the order in which the pivot table will perform the operations. To make changes to this order, select any of the calculated items you see and then click Move Up, Move Down, or Delete, as appropriate.

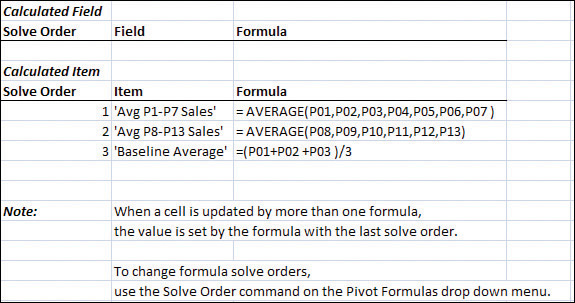

Documenting formulas

Excel provides a nice little function that lists the calculated fields and calculated items used in a pivot table, along with details on the solve order and formulas. This feature comes in especially handy if you need to quickly determine what calculations are being applied in a pivot table and which fields or items those calculations affect.

To list your pivot table calculations, simply place your cursor anywhere in the pivot table and select Fields, Items, & Sets and then select List Formulas. Excel creates a new tab in your workbook that lists the calculated fields and calculated items in the current pivot table. Figure 5-39 shows an example of a tab created by the List Formulas command.

Next steps

In Chapter 6, “Using pivot charts and other visualizations,” you will discover the fundamentals of pivot charts and the basics of representing your pivot data graphically. You’ll also get a firm understanding of the limitations of pivot charts and alternatives to using pivot charts.

![This figure shows the Custom Column dialog box in Power Query. The new column is called Revenue and uses a formula of =[Units]*[Price].](Images/05fig30.jpg)

![The Measure dialog box shows a formula of =[Max of Price]-[Min of Price].](Images/05fig33.jpg)