IN FORMER TIMES, FEW PARTS of northern Europe were without waterlogged and often peat-covered tracts of country. These marshy or boggy areas were seen by townspeople and country-dwellers alike as desolate and even dangerous wastes to be shunned if they could not be drained for profitable farming, although they often provided their local communities with peat for fuel, reeds and sedge for thatching, rough hay for bedding livestock, summer grazing, and a source of wildfowl. Nowadays we value these areas for the richness and diversity of vegetation and wildlife they support, for their contribution to the diversity of an increasingly urbanised and intensively farmed landscape, and for their beneficial effects in helping to maintain the water quality of rivers and alleviate flooding. As they accumulate, lake sediments and peats incorporate pollen grains and larger plant remains, and sometimes human artefacts (and even occasional humans!), as well as such other evidence of events in their surroundings as ash from volcanic eruptions, charcoal from burning of the surface vegetation, and pollutants such as soot, heavy metals, and radionuclides from cold-war bomb testing and the Chernobyl disaster. Peatlands thus provide a historical archive of extraordinary interest and value (Chapter 2), along with a record of their own origin and development.

WETLANDS AND PEATLANDS: A DIVERSITY OF WET HABITATS

‘Wetland’ is a convenient all-embracing label for wet places, familiar to everyone, and much used by geographers, planners and conservationists. The Ramsar conference of 1971 defined wetlands as ‘areas of marsh, fen, peatland or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt, including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed 6 m.’ So wetland is a very broad concept; for some purposes it is too broad, bringing together such disparate habitats as the shallow sea (outside the scope of this book), the aquatic communities of lakes and rivers described in the previous chapter, and saltmarshes, which will be dealt with in Chapter 18.

This and the next two chapters are about the remaining wet places. These are very diverse, and the words describing them in ordinary speech have tended to be used differently, and sometimes interchangeably, in different parts of the country. The general practice among plant ecologists is to use the word reedswamp for reed-like vegetation in standing water, bog (or moss) for vegetation of acid peat, fen for vegetation on peats that are calcareous or at least influenced by water that has drained from mineral ground (bog and fen are peatlands), and marsh for vegetation of waterlogged mineral soils; the term fen carr (or simply carr) is used for wet fen scrub or woodland (Chapter 6). The term mire was introduced by Godwin as a general term to embrace both bogs and fens (to parallel the similar use by the Scandinavians of their word myr). Because the line between silty peats and highly organic wet mineral soils can only be arbitrary, and is often not reflected in the vegetation, it is convenient to extend the scope of ‘mire’ to include vegetation of wet sites on which there may be little or no peat developed, and that is what I shall do in this book.

PEAT AND THE ORIGIN OF PEATLANDS

Peat consists of the partly decomposed remains of the plants that once grew upon its surface. It develops in wet places where the annual input of dead organic matter from the vegetation exceeds annual breakdown, so that organic material accumulates of which the lower parts become waterlogged. The balance between the rate of input and the rate of breakdown of organic matter in the surface layers is crucial, and the rate at which peat accumulates is always much less than the rate of production of organic matter by the vegetation.

Peatlands can originate in three ways. First, and most obviously, peat-forming vegetation can develop in places where the water-table reaches the surface in low-lying hollows (topogenous mires), or emerges in springs or seepages on a hillside (soligenous mires), and the soil is permanently wet. Many of our smaller valley bogs and fens (and some larger peatlands) are of this kind. Second, peatlands have often developed through the infilling of pools, lakes and the freshwater upper reaches of estuaries by hydrosere development. This process took place extensively in the lake-dotted landscape left by the last glaciation. Third, in a wet enough climate, bog may grow up over previously freely drained ground by paludification, drainage first becoming impeded by development of an impermeable ‘pan’ in the soil; once significant peat growth has taken place the peat itself acts as an effectively impermeable layer. Thousands of hectares of blanket bog in the north and west of Britain and Ireland began growth in this way. All three of these processes are important. The second, hydrosere development, has some particular points of interest and we shall consider it in more detail, but that should not blind us to the importance of the other two.

EARLY HYDROSERE SUCCESSION: OPEN WATER TO FEN CARR

The hydrosere – development from open water to dry land with the progressive accumulation of sediment and peat – is a classic example of plant succession. Ideally, on a gently shelving lake shore, the successive zones of vegetation from open water to dry land can be expected to parallel the sequence preserved in the peat under the later stages in the succession. Peat borings in the larger lowland peatlands of Britain and Ireland record evidence of hydrosere development almost everywhere. It may thus seem disappointing that really good examples of hydrosere succession in action at the present day are hard to find. A major reason is that in terms of geological time lakes are short-lived, and sediment accumulation and hydrosere development are fast. Most of the hydrosere development that could readily take place in the lakes left by the retreating ice took place within the first few thousand years of the Post-glacial, and we are too late to see it. But plenty of illustrative examples of hydroseres do exist, some of long standing, some ‘secondary successions’ following disturbance by man.

The Esthwaite fens

A good example of hydrosere development is the fen at the north end of Esthwaite Water in the Lake District (Fig. 169), mapped by W. H. Pearsall in 1914–15 and again in 1929, as described by Tansley (1939), and re-mapped by Pigott & Wilson (1978) in 1967–69. Between the time of the Ordnance Survey of 1848 and 1968, different parts of the shore advanced between 28 and 47 m, an average of about 0.2–0.4 m a year. However, this advance has not been uniform, and Pearsall’s observations seem to have spanned a period of particularly rapid change. There is a striking difference between the vegetation sequence close to the mouth of the Black Beck (which brings in abundant inorganic silt) and that on the progressively less-silted shoreline farther east. At the time of Pearsall’s observations, the fringing reedswamp near the mouth of the stream consisted of common reed (Phragmites australis) and bulrush (Typha latifolia), succeeded by a rich and diverse fen vegetation, in which prominent species included tufted-sedge (Carex elata), yellow iris (Iris pseudacorus) and, especially in the strip alongside the stream itself, reed canary-grass (Phalaris arundinacea), meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) and purple small-reed (Calamagrostis canescens). The fen in turn was colonised by willows and sallows, especially purple willow (Salix purpurea), crack-willow (S. fragilis) and grey sallow (S. cinerea), recalling the silted alder–sallow woods of Chapter 6. Where silting was only moderate, the outer zone of the reedswamp was composed of Schoenoplectus lacustris, with Phragmites inshore. This gave way to a fen dominated by Carex rostrata or C. elata, colonised in due course by Salix cinerea and developing through an open carr stage with a great diversity of species to a closed Salix carr. On the eastern shore, farthest from the beck and with little silting, the reedswamp was again of Schoenoplectus lacustris and Phragmites, but subsequent development led quickly through a stage with Carex rostrata and marsh cinquefoil (Potentilla palustris) to a species-poor community dominated by purple moor-grass (Molinia caerulea), often with much bog-myrtle (Myrica gale).

FIG 169. North Fen, Esthwaite, Cumbria, May 1981, a dozen years after Pigott & Wilson’s survey. Common reed (Phragmites) is the main colonist of open water along most of the shoreline, supplanted within a few decades by sallow and alder carr. The large pine tree succumbed about 1990.

Pearsall’s maps demonstrate convincingly the advance of the successive zones of vegetation, and support the idea that the zonation in space of vegetation types from the open water up into the fen does indeed reflect succession in time at any particular point. The more recent observations confirm this picture, but also make it clear that succession has not consisted simply of the gradual advance of the reedswamp into the lake, followed by an orderly migration of successive zones all moving at the same rate. In fact, different species and different boundaries have often moved at different times and different rates, so that zones have contracted and expanded over the years, and different species have sometimes moved together, and sometimes not. Thus Pearsall’s maps show the reedswamp vigorously colonising open water, and also extensive encroachment of fen onto former reedswamp, while Salix cinerea rapidly and almost alone colonised established fen. Since 1929 the reedswamp has continued to invade the open water of the northeastern corner of the lake, but there has been scarcely any movement of the reedswamp–fen boundary except close to the mouth of the Black Beck. Salix cinerea has continued to colonise the fen, and alder, present as only a few scattered trees in 1929, has spread throughout almost the whole of the area; the two species now form dense fen carr on ground that was fen dominated by Carex elata in 1929, and reedswamp dominated by Phragmites (but probably with some Carex rostrata) in 1914–15. Sedges are still abundant under the carr, now mainly lesser pond-sedge (Carex acutiformis) in the more silted areas, and C. elata and C. rostrata elsewhere. In fact, at the present time open fen has all but disappeared, and there is an almost direct transition from reedswamp to carr. This may reflect partly the increased supply of nitrate and phosphate to the lake and fen in recent decades, and partly the exclusion of grazing livestock.

The Norfolk Broads

The Norfolk Broads provide the most extensive examples of recent (secondary) hydrosere succession in Britain, and some of the best documented. Peat growth in the low-lying Broadland valleys (Fig. 170) began during the Atlantic period (Chapter 2), and peat borings show that the vegetation quickly developed to fen carr, which for many centuries accumulated brushwood peat, often to a depth of 3 m or more. In Romano-British times sea level rose sufficiently to bring about a return to open fen conditions in many places. Broad levées of silt were built up along the Broadland rivers. These no longer appear as levées because of subsequent peat growth, but they underlie strips of marsh, called ronds, which often separate the broads from their neighbouring rivers. The Norfolk Broads as we know them originated as medieval peat (or ‘turf’) diggings cut down into the layers of peat that had filled the valleys. The earliest records of peat digging are from the mid twelfth century. For the next two centuries there is abundant documentary evidence of a flourishing peat industry in all the main areas where broads exist at the present day. In the latter half of the fourteenth century a change in the words used to describe areas that were formerly turbary suggests that the ground was becoming wetter; at the same time there is evidence of decline in the sales of peat, and of increasing difficulty in its extraction. By the fifteenth century the documents suggest that peat had largely given way to open water and fen. In all, medieval peat digging had moved some 25 million cubic metres of peat. Large as this figure is, peat winning on this scale was certainly within the capacity of the medieval population of the area. A good day’s digging in nineteenth-century Broadland yielded 1000 turves, each of about a quarter of a cubic foot (say 7 litres). If each of the 28 parishes that now share the Broads within their parish boundaries had had 20 men working in the turf pits for three weeks of the year, the volume of peat represented by the Broads could have been removed in about three centuries (Lambert et al. 1960).

FIG 170. Broadland: looking eastwards across the peat-filled valley of the River Ant, just downstream from Barton Broad. Part of Reedham Water in the foreground, Turf Fen drainage windmill on the riverbank, fen and a tiny broad beyond. (© Adrian Warren & Dae Sasitorn/ www.lastrefuge.co.uk)

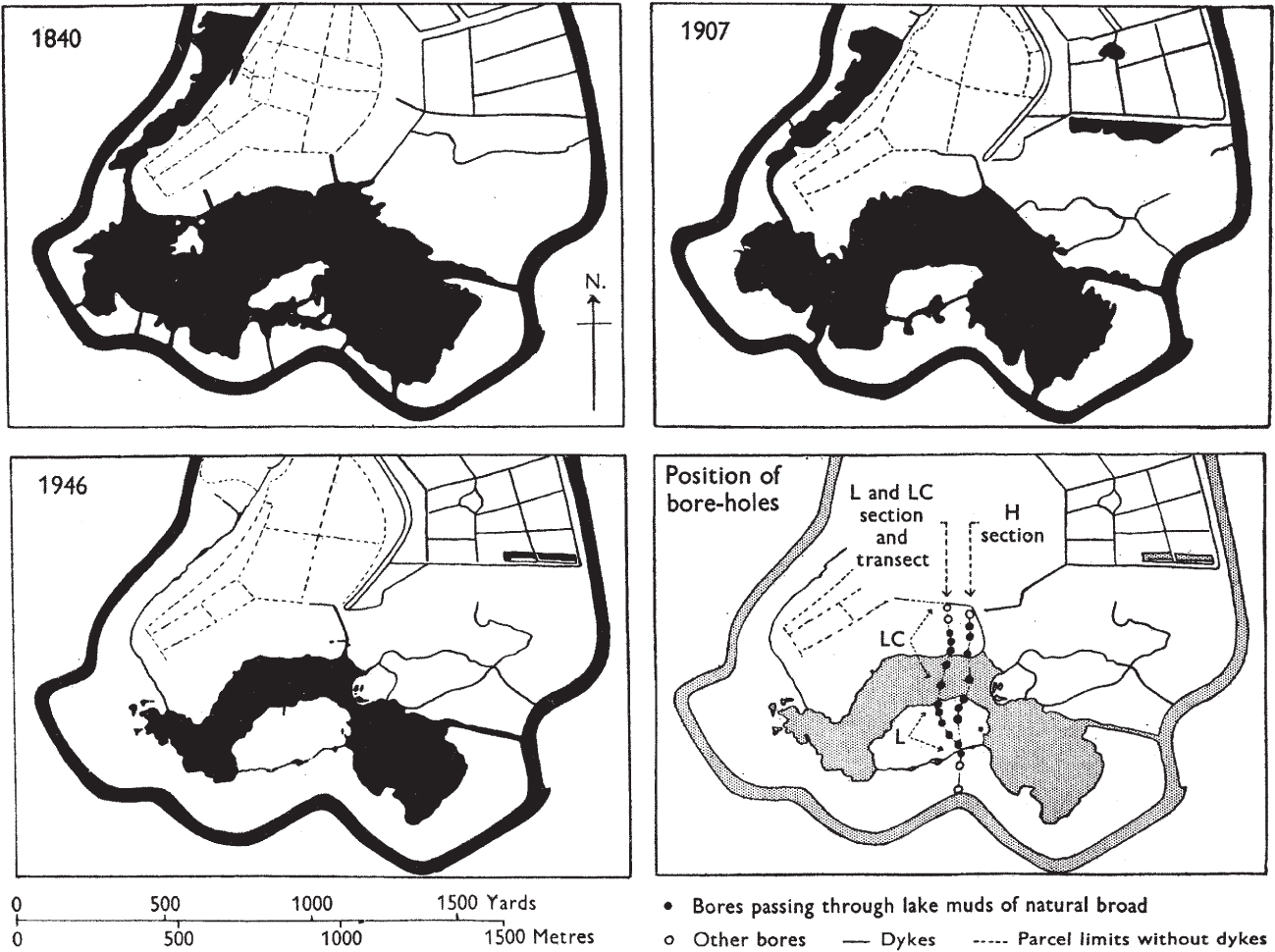

Because of their origin, the basins of the Norfolk Broads are shallow (seldom more than 3 m and often less than 2 m deep), with relatively flat bottoms and steep sides. Some silting and accumulation of nekron mud had to take place before the water became shallow enough (c. 1 m) for reedswamp plants to become established, but once that point was reached the development of reedswamp and fen often took place very rapidly. This is strikingly shown by the decrease in area of many of the Broads since the tithe maps of 1838–41 (Fig. 171). Some former broads had already become overgrown by that time. Several, such as Strumpshaw and Hassingham Broads in the Yare valley and Woodbastwick Fen in the valley of the Bure have filled in (or practically so) since.

FIG 171. The outline of Hoveton Great Broad, Norfolk, from the tithe map of 1840, the Ordnance Survey of 1907, and aerial photographs in 1946. From Lambert & Jennings (1951).

The first reedswamp plants to colonise the open water of the northern Norfolk Broads are the lesser bulrush (Fig. 172a), and in places the common club-rush (Schoenoplectus lacustris), giving way in shallower water or on wet peat to common reed (Fig. 172b). In the Yare valley these are replaced by the tall grasses Glyceria maxima and Phalaris arundinacea, corresponding with heavier silting and a richer supply of nutrients (Chapter 12). Phragmites maintains itself as a dominant only until the root-felt mat overlying the soft open-water mud has stabilised sufficiently to keep its surface just above water level. At that stage it is invaded by fen species, amongst which the greater tussock-sedge (Fig. 172b) is often very prominent. The tops of the Carex tussocks stand well above water level, and provide a dry foothold for tree and shrub seedlings. The tussock fen quickly grows up into a closed carr. With increasing shade, and increasing weight of the trees and bushes, the surface mat in which the tussocks are rooted begins to subside and break up; mature ‘swamp carr’ is full of rolling tussocks and a tangle of leaning trees rooted in semi-liquid peat. The surface is slowly stabilised by the gradual accumulation of brushwood peat. In sites farther from the rivers, and thus less exposed to fluctuations of water level, the Phragmites mat may be colonised by the lesser pond-sedge (Carex acutiformis). This does not form tussocks like C. paniculata, so shrubs cannot colonise the fen until a thicker mat of fen peat has accumulated. The unconsolidated muds under the ensuing ‘semi-swamp carr’ still give a quaking ground, but the surface is much more stable and most of the trees remain upright (Fig. 173). In areas still farther from the fluctuating water of the main rivers the Phragmites mat is often invaded by the great fen-sedge (Cladium mariscus, Fig. 188b), in East Anglia known simply as ‘sedge’. Cladium has coarse strap-shaped evergreen leaves with sharp serrated edges, which may be 2 m or more long, and which live for 2–3 years. When they die they are slow to decay, remaining propped among the living leaves to form a continuous thick elastic mattress. Owing to this habit, Cladium excludes most other plants, though Phragmites maintains itself for a long time by means of its vigorous and extensive underground rhizomes. Colonisation by the fen carr shrubs is long delayed, and when it ultimately takes place the carr is rooted in a firm and massive layer of Cladium peat.

FIG 172. (a) Fringing reedswamp of lesser bulrush (Typha angustifolia), Barton Broad, Norfolk, July 1997. (b) Common reed (Phragmites australis) and greater tussock-sedge (Carex paniculata) at margin of Upton Little Broad, Norfolk, September 1982; young sallows and downy birch rooted in the sedge tussocks. Lesser pond-sedge (Carex acutiformis) was prominent farther along the edge of the broad.

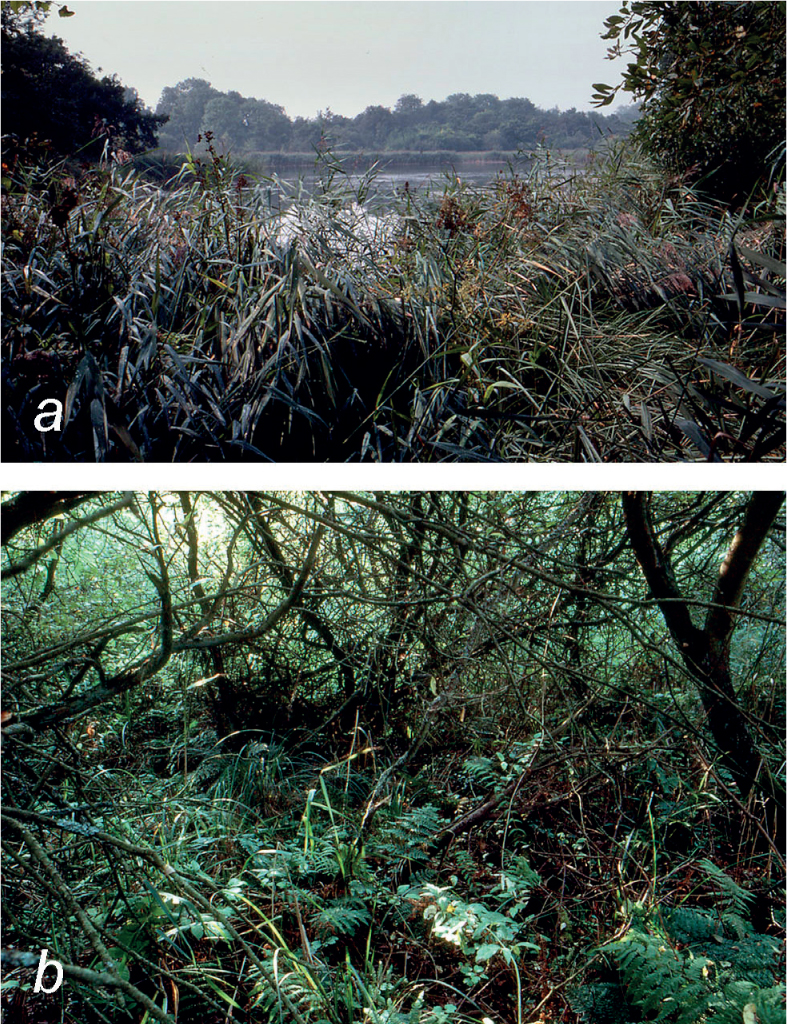

FIG 173. (a) Upton Little Broad, Norfolk, September 1982. Dense common reed and ‘sedge’ (Cladium); open water glimpsed through a gap in the sallow carr. (b) Dense fen carr of sallow (Salix cinerea) near Upton Great Broad, September 1982W2. Broad buckler-fern (Dryopteris dilatata) and brambles are prominent under the sallow canopy.

In the Broads, as at Wicken Fen in Cambridgeshire, many of these pure dense stands of Cladium were regularly cut by the fenmen for thatching and kindling. If the cutting is not done oftener than once in four years the Cladium can maintain itself apparently indefinitely, accompanied by a scattering of plants surviving from the reedswamp, such as Phragmites and yellow loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris). If it is cut more frequently, say once in two years, the plant is enfeebled by the frequent loss of living leaves and Molinia enters the community and comes to share dominance with Cladium. Other plants come in at the same time, such as wild angelica (Angelica sylvestris), hemp agrimony (Eupatorium cannabinum), milk-parsley (Peucedanum palustre, Fig. 188a, the food-plant of the swallowtail butterfly) and marsh pennywort (Hydrocotyle vulgaris); a comparable mix of species can result from cutting Phragmites stands for thatching-reed. The accompanying plants are conspicuous after the cutting of the sedge or reed, but tend to be crowded out as the Cladium and Molinia or Phragmites resume dominance. If the vegetation is cut every year, Cladium and Phragmites succumb and Molinia remains dominant alone. Many species grow along with the Molinia, including meadowsweet, devil’s-bit scabious (Succisa pratensis), marsh valerian (Valeriana dioica) and meadow thistle (Cirsium dissectum). The species composition and ecological relationships of these communities will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter.

THE LATER HYDROSERE: THE FATE OF FEN CARR

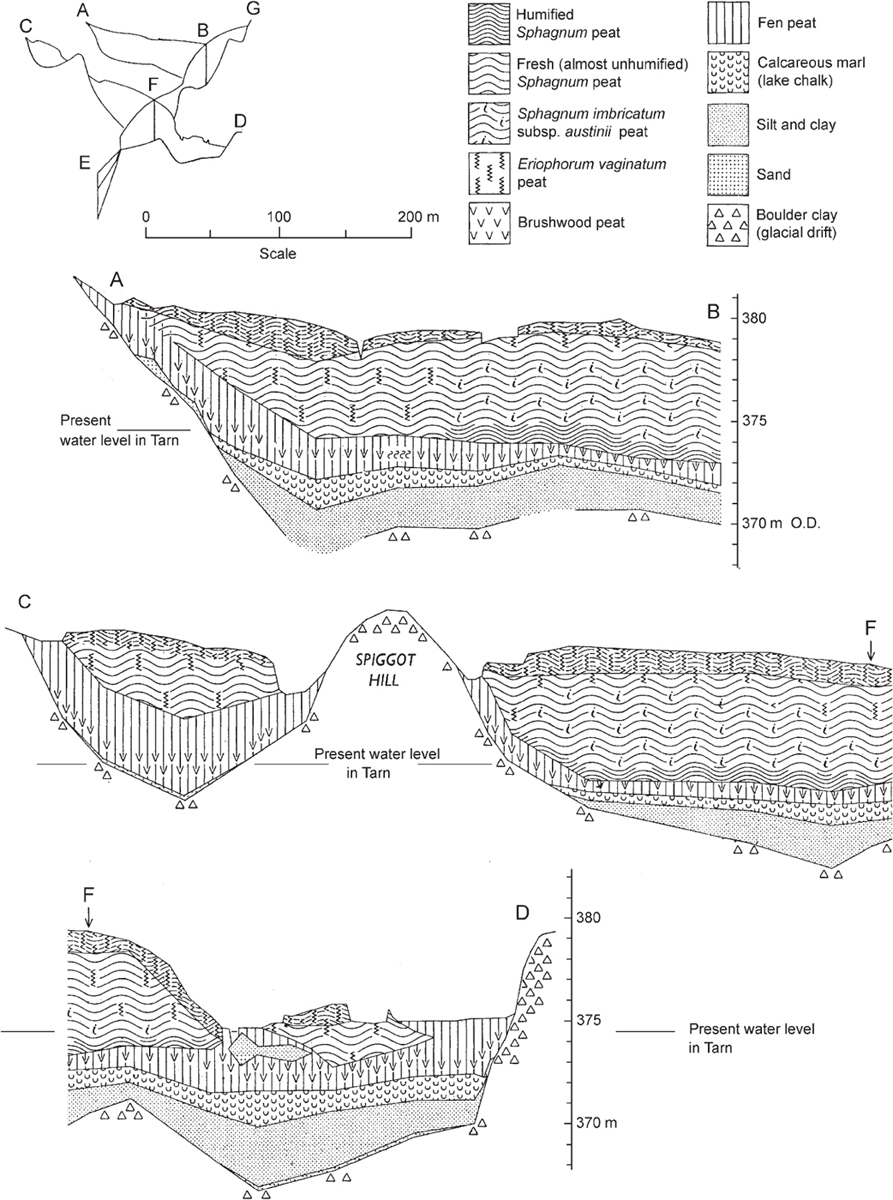

What becomes of fen carr? To answer this question we are thrown back onto the evidence of peat borings, and to inference from present vegetation. In some places the accumulation of wood peat may in due course raise the ground surface sufficiently above the water-table for sallow and alder carr to be replaced by damp oak or ash wood. This would certainly be the ultimate fate of many small pools or cut-off sections of old river channel. Godwin & Turner (1933) found evidence of development of this kind at Calthorpe Broad in Norfolk, and there are a few oak and ash trees in the older parts of the carr at Esthwaite. A classic site showing a complete zonation from Typha reedswamp and Carex paniculata fen, through sallow and alder carr, to birch and oakwood is Sweat Mere in Shropshire (Tansley 1939), but the birch and oakwood there is on drier ground that does not grade continuously with the wetter fen peats, and it is probably not part of the hydrosere (Sinker 1962). In fact, evidence of extensive hydrosere succession culminating in woodland is rare. In many sites the peat stratigraphy shows that brushwood peat laid down under fen carr was succeeded by the growth of thick layers of Sphagnum peat (Fig. 174), and observation of present-day vegetation gives some indication of how this has come about.

FIG 174. Sections of the raised bog and fens at Malham Tarn Moss, Yorkshire, showing succession from lake deposits, through fen and brushwood peat to ombrotrophic bog. Letters A–G correspond with the map in Fig. 200. Malham Tarn lies in a relatively infertile landscape; the main reedswamp species is Carex rostrata, so there is little evident differentiation of reedswamp and fen peat. Adapted from Pigott & Pigott (1959).

In the wet climate of Britain and Ireland, rainfall exceeds potential evaporation at least for most months in the year. Consequently, the continued growth of wood peat in an extensive fen basin, rather than raise the ground surface above the water-table, will tend to carry the water-table up with it. However, if peat growth makes the ground a little drier, it does have the effect of gradually raising the surface out of reach of flooding by mineral-rich drainage water from the surrounding country. The growing peat comes to depend wholly upon rainfall for its water supply. The result is that the surface layers become leached and acid. The sallows of the young carr are often replaced wholly or in part by downy birch (Betula pubescens), and shade- and mineral-tolerant Sphagnum species (such as S. fimbriatum, S. palustre, S. fallax and S. squarrosum) become established, forming a carpet over the ground in the shade of the trees and bushes (Fig. 175). Godwin & Turner described fen carr at this stage of acidification near Calthorpe Broad. The same process is taking place locally under Betula pubescens at Esthwaite, and similar examples of fen carr or birchwood on peat with a Sphagnum ground-layer can be seen in the Broads and many other places. The next stage in the succession follows opening-up of the canopy. This may be due to the loose wet Sphagnum carpet waterlogging the root systems of the woody plants, enfeebling or killing them directly, or making them more liable to windthrow – or simply preventing regeneration as they come to the end of their life span. Conditions are now favourable for the growth of the common peat-forming Sphagnum species, such as S. papillosum and S. magellanicum. Once a continuous bog surface has developed, dominated by these mosses, it can continue to develop peat virtually indefinitely.

FIG 175. Sphagnum carpet under downy birch and sallow, Malham Tarn, Yorkshire, July 1962W4.

A bog of this kind, raised above the mineral-rich drainage of the surrounding country, is called a raised bog. The bog is dependent for its water supply on the rain falling directly on its surface (it is ombrogenous – ‘rain-formed’), and the mineral nutrient regime of the vegetation reflects the balance between additions of solutes from rain, blown dust and other sources, and losses in drainage water (it is ombrotrophic – ‘rain-fed’). The same is true of the blanket bog that covers wide expanses of country in the rainy west of Britain and Ireland and on the high ground of the Pennines and elsewhere. Ombrotrophic bogs have been the commonest end-point of large-scale hydroseres in Britain and Ireland since the last glaciation. Ombrotrophic peats covered large tracts of ground in such areas as the Somerset Levels, the Lancashire–Cheshire plain, the country south of the Humber, the Solway district and (especially) the midland plain of Ireland. However, peat cutting and drainage have changed many former raised bogs beyond recognition, and in Britain good intact raised bogs are now rare. Some examples are described in Chapter 15.

Directions of vegetational change, and rates of peat accumulation

The examples of early hydrosere development described above are instances in which the course of changes in the vegetation can be demonstrated in some detail from clear direct evidence. The probable course of succession at other sites can often be inferred from their present vegetation. Peat borings yield a wealth of evidence of the general course of succession from different places. With the timescale provided by pollen analysis or (better) C-14 dating, they also give the means to estimate rates of accumulation of peats and other sediments, and the duration of the various phases in a hydrosere.

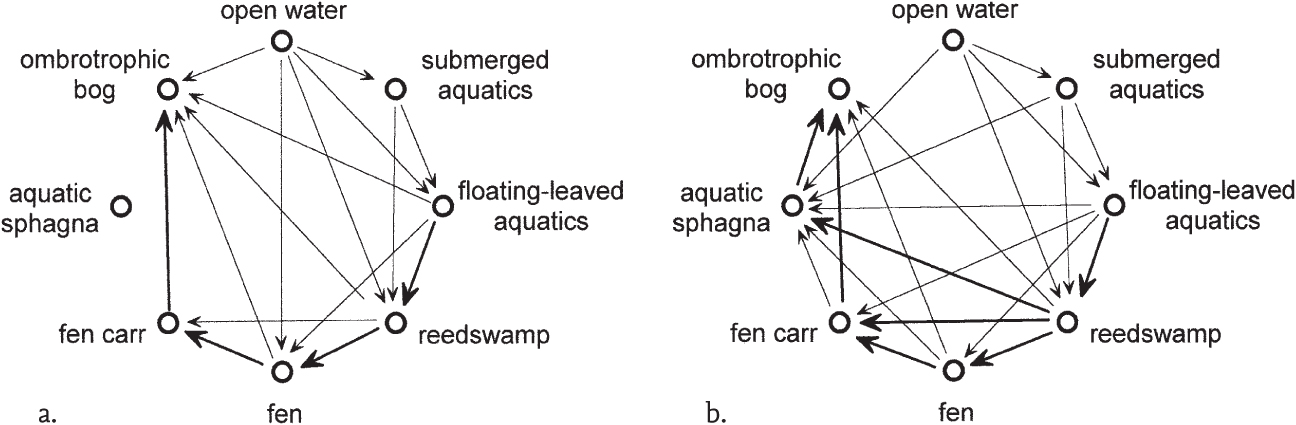

The sequences of hydrosere stages in the peat stratigraphy from 20 pollen diagrams were analysed by Walker (1970). These sites would generally have been chosen to give long undisturbed profiles near the centre of a mire basin. The commonest sequence recorded was: open water with floating aquatics → reedswamp → fen → fen carr → bog – the succession outlined in the preceding pages (Fig. 176a). Walker also looked at the predominant sequences in a wider range of sites, and in these another series of transitions emerged as important, going from open water or reedswamp to bog either direct, or through a floating Sphagnum stage (Fig 176b). But, as these diagrams show, a surprisingly wide range of possible transitions are recorded in the peat. Several of the common intermediate stages of the hydrosere can be passed through very quickly, or even apparently omitted altogether (but there is usually at least a brief reedswamp stage), and most of the common hydrosere transitions can be reversed. Ombrotrophic bog stands out as the one vegetation type that rarely turns into anything else; once Sphagnum becomes established, at whatever stage of the hydrosere, development to bog as the next stage becomes almost inevitable.

FIG 176. The frequency of transitions between vegetation stages in the hydrosere from the evidence of peat borings: (a) from the profiles used for 20 pollen diagrams (heavy lines show transitions observed six or more times); (b) from the predominant course of succession at a larger number of sites (heavy lines show transitions observed nine or more times). The arrows show only ‘progressive’ transitions, and the rarest transitions are omitted. Based on the data of Walker (1970).

The time taken for succession from open water to fen or bog can vary widely. Peat profiles show that, once a hydrosere reaches the floating-leaved macrophyte stage, conversion to fen has frequently taken less than 1000 years – sometimes very much less (as in the Norfolk Broads), and rarely more than twice that time. Direct succession from open water through reedswamp (and sometimes swamp carr) to bog can also be rapid, rarely taking more than 2500 years. If there is a persistent fen stage the whole process takes longer; exceptionally it can be complete in less than 1000 years, but 2500–4000 years is more usual. Succession in small ponds or pools can of course be much quicker than this.

There are great variations in the rate of accumulation of almost all kinds of peats and freshwater deposits but, perhaps surprisingly, there seems to be little consistent difference in the rate of growth between one kind of deposit and another. A common rate of accumulation for fen and bog peats is 5–10 cm a century (corresponding to some 10% of the production of organic matter by the plants), but the rate of accumulation may be substantially more, or very much less than this. The actual rate of accumulation at any particular place and time represents the difference between additions to the deposit and losses due to erosion and decomposition. If conditions favour oxidation of organic matter, at least seasonally, the peat may grow slowly or not at all, and a modest amount of erosion can have the same result. The effect of shrinkage and oxidation in bringing about the wastage of peat is graphically demonstrated by the ‘Holme post’, close to the former Whittlesey Mere 10 km south of Peterborough. This is a cast-iron post, bolted to oak piles driven into the underlying clay so that its top was level with the peat surface at the time the surrounding fens were being drained in 1848. By 1860 the level of the peat had fallen by over 1.5 m; by the early twentieth century the post stood about 3 m above the ground, and the level of the surface changed little for several decades. With deeper drainage, the level has since fallen by a further 80–90 cm (Hutchinson 1980).

Interrelations of hydrosere succession with topography and climate

The successions that have been discussed in this chapter are typical of the hydrosere recorded in extensive peat deposits that have grown up over former lake basins. However, even a cursory inspection of a few lakes will show that hydrosere development does not take place everywhere. Lee shores of lakes are often wind-eroded, and although they may show a clear zonation of vegetation there is often no peat accumulation. Deep, steep-sided lakes often show little sign of succession. Initiation of a hydrosere typically depends in the first place on the accumulation of open-water silt or mud until the water is shallow enough for floating-leaved and emergent aquatic plants to become established. It therefore often takes place in sheltered bays or where an inflow stream brings in a supply of inorganic silt. The character, rate and extent of hydrosere development are also influenced by the nutrient supply provided by the surroundings, as we have seen at Esthwaite. A fertile lowland agricultural landscape will provide the nutrients for vigorous growth of reedswamp, fen and carr, as in the Norfolk Broads. In blanket-bog country on hard acid rocks, if hydrosere development takes place at all it is likely to be from a low open reedswamp of Carex rostrata to acid fen (Chapter 14) and bog. Thus there are several reasons why the vegetation of a lake may show little change, and at some sites old photographs attest remarkable stability over long spans of time.

Although different kinds of lake deposits and peats can accumulate at similar rates, deposits in shallow water (calcareous marl, detritus muds, reedswamp peat) often accumulate faster than those in deeper water, with the effect of steepening the underwater profile of the lake margin. There is also a common tendency for swamp vegetation to grow out as a floating raft over unconsolidated sediments or even open water, especially in small sheltered lake basins (Sinker 1962). This can be seen in places as far apart as the Norfolk Broads and the Burren. Around the margins of a small but deep lake basin close under Mullagh More, peat boring showed normal succession from calcareous marl (precipitated by the submerged green alga Chara in shallow water), through reedswamp, to fen dominated by black bog-rush (Schoenus nigricans). In the deeper centre there is little marl, and Cladium reedswamp is growing out as a rhizome mat over open water or very loose detritus mud. Figure 177 shows a similar site a few kilometres away, with a similar history. This pattern of development seems to have taken place in a number of lakes in the flat limestone country of the southeast of the Burren, but peat cutting and erosion have usually stripped off most of the fen peat, leaving almost level marl flanges bearing relic patches of peat, surrounding a deep centre, as at Loch Gealáin, a kilometre southwest of Mullagh More, and at Skaghard, Cooloorta (Fig. 178) and Travaun Loughs a few kilometres to the northeast. In sites poor in calcium and nutrients, floating rafts of Sphagnum, bound together by the rhizomes of such plants as common cottongrass (Eriophorum angustifolium) and bogbean (Menyanthes trifoliata) can grow out over pools and lakelets to form a quaking mattress of the kind known by the nicely descriptive German word Schwingmoor; in Ireland such floating mats of vegetation are called scragh or scraw. Small-scale examples can sometimes be seen in old peat cuttings. It has been suggested that Wybunbury Moss near Crewe developed as a schwingmoor over a small deep kettlehole lake in the glacial drift which covers the Cheshire plain, but it is likely that the hollow in which it lies is at least in part due to subsidence following solution of salt deposits in the underlying Triassic rocks (Poore & Walker 1959; Green & Pearson 1977), as at Chartley Moss in Staffordshire.

FIG 177. Rinnamona Lough, near Killinaboy, Co. Clare, July 1971. The marginal vegetation is advancing over open water, leaving a deep central pool. The depth of the basin exceeds 13 m.

FIG 178. Cooloorta Lough, in the eastern Burren, July 1970. A substantial lake, with a deep centre surrounded by extensive marl flats. These were probably exposed by stripping of a former peat cover by cutting for fuel, and erosion, but are now largely vegetated with a thin community of shoreweed (Littorella uniflora), lesser water-plantain (Baldellia ranunculoides) and the moss Scorpidium scorpioides.

In many large peat deposits there is a correlation between the stages of the hydrosere and the course of climatic change since the last glaciation. Fen and fen carr became established widely as the climate became warmer at the end of the Late-glacial period, about 11,500 years ago (Chapter 2), and were extensive and persistent through much of the Boreal period when the climate was more continental than now, and there may have been more grazing pressure from native herbivores. At many sites, the transition from fen carr to ombrogenous bog coincided roughly with the climatic change at the Boreal–Atlantic transition, about 8000 years ago, when the climate became much more oceanic in character. There is little Sphagnum peat anywhere before that time. In more recent periods, fen has generally given way rather quickly to ombrogenous peat except where rising sea level kept pace with the accumulating peat, as in the Broadland valleys and much of the Cambridgeshire Fenland. In the Somerset Levels, Shapwick Heath and the neighbouring moors were still part of an open estuary accumulating grey clay at the Boreal–Atlantic transition, and the whole succession from reedswamp to ombrotrophic bog took place in a relatively uniform climate (Godwin 1975).

It is obvious that the kind of succession outlined earlier in this chapter cannot go to completion over the whole of a mire system. Growth of peat in one place will affect water movement and water levels in other parts, and however extensively ombrotrophic bog develops, the mineral-rich drainage from the surroundings must go somewhere. Some of the consequences can be seen in Figure 174. As raised bog developed in the centre of the basin, the level of the marginal fens gradually rose, fen extending peripherally out over mineral ground while the bog encroached on its inner edge. In this ‘lagg’ fen (Chapter 14), separating the raised bog from the mineral soil, succession went sometimes from fen to carr, sometimes back again. Clearly, the more closely bog growth confines mineral-rich drainage water in this marginal belt of fen, the more will conditions inhibit further development to acid bog. The result is that the whole complex will tend to reach a steady-state pattern of ombrogenous bog and fen.

Two points may be emphasised in conclusion. First, although in a simple hydrosere there is a broad correspondence between zonation from open water to fen and the succession recorded in the fen peat, many of the changes taking place in large mire systems are not closely mirrored in zonation. In particular, the succession in the central parts of a mire complex is often different from that close to either the landward or the lakeward margin. Riverbanks and exposed lake shores often show striking zonations that are essentially stable; there is no peat accumulation and no succession – or succession, if it occurs, may go either way. Second, hydrosere succession may be seen as a process of readjustment of the vegetation to natural or artificial disturbance of the habitat. Many examples are the result of human activity – the creation of a field pond, a change in lake level, or the digging of the Norfolk Broads. The massive hydrosere development recorded in Post-glacial peats followed as a natural consequence of the massive topographic and climatic upheavals during and since the last glaciation.