THE SORT OF CHANGE we considered in the last chapter is often too slow to be immediately perceptible. It generally takes place on a timescale of at least decades, and often centuries or even millennia, and in some places long spans of time may pass with little change at all. What is more obvious is the pattern of different kinds of plant communities, and the contrasts between the peatland vegetation in different places. Sometimes patterns in space reflect sequences in time, but often they do not.

CHEMICAL FACTORS IN PEATLAND VEGETATION: CATIONS AND pH

On a broad scale, there is a major ecological distinction between ombrogenous or ombrotrophic bogs and the rest (Fig. 179). The terms ombrogenous (‘formed by rain’) and ombrotrophic (‘rain-nourished’) are in many contexts interchangeable; these bogs depend for their water and solute supply on rain and other airborne sources alone, and are correspondingly always nutrient-poor and acid, and typically form deep peat. Ombrogenous bogs cover wide tracts of country in Britain and Ireland, and are the subject of Chapter 15.

All peatlands other than ombrogenous bogs receive water both from rain and from groundwater bearing nutrients and other solutes from neighbouring mineral ground – they are at least in some degree minerotrophic. What may loosely be called ‘fens’ in the British and Irish tradition are more or less calcareous, with a near-neutral pH (usually between 6 and 7.5). They are generally dominated by sedges (such as great fen-sedge, Cladium mariscus, black bog-rush, Schoenus nigricans, and many sedges of the genus Carex), reeds (such as the common reed, Phragmites australis, and purple small-reed, Calamagrostis canescens) and broad-leaved herbs. True mosses can be prominent but Sphagnum species are much less so and often absent altogether. By contrast, bogs (including ombrotrophic bogs) are poor in calcium and mineral nutrients, and acid, with pH often between 3.5 and 4.5. They are typically dominated by Sphagnum (‘bog-mosses’), sedges (‘cottongrasses’) of the genus Eriophorum and dwarf shrubs of the heather family (Ericaceae) including common heather (Calluna vulgaris), cross-leaved heath (Erica tetralix) and cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos).

FIG 179. Malham Tarn Moss and fens, September 1959. This shows the raised bog to the left clearly above the level of the inflow stream, and the almost level surface of the fens to the right. Continued growth of fen-carr shrubs since has largely obscured this view.

This bog–fen distinction reflects the water supply to the site. Measurements of pH from a large sample of peatland sites tend to show a bimodal (two-peaked) distribution, with one peak centred at about pH 4 and the other at about pH 6.5. This is because the pH of bogs is buffered by the organic acid groups on the peat colloids, whereas the pH of fens (with the ion-exchange sites on the peat saturated by calcium and other cations) is buffered by the CO2–bicarbonate system in the water (Chapter 12). Intermediate pH values are possible (and are often associated with interesting vegetation), but they are vulnerable and easily tipped one way or the other by calcareous dust or (particularly) by ‘acid rain’.

To many English people the word fen calls up a picture of the Fenland of East Anglia. But these tall reedy fens are only one corner of the range of variation in ‘fen’ vegetation, and a Scandinavian (or indeed an Irish) botanist would take a very different view of what constitutes a typical fen. Much of the diversity of fens can be thought of in terms of two major directions of variation, determined by peat and water chemistry and the availability of plant nutrients.

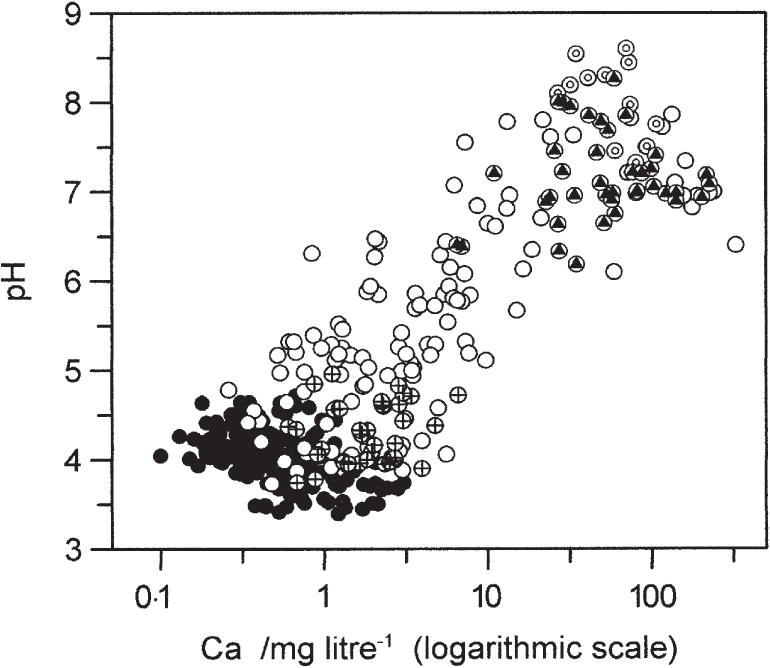

Figure 180 shows pH plotted against log calcium concentration (log [Ca]) from a number of peatland sites (as pH is a logarithmic measure of acidity it is appropriate to plot it against a logarithm). The ombrotrophic bog samples, with low [Ca] and pH, form a cluster at the bottom end of the graph, overlapping with the minerotrophic bog/poor-fen samples; these are concentrated in the pH range 3.5–4.5. The middle part of the graph is more thinly populated with points, but as pH rises above 6 we are into another dense cluster of points at pH 6.5–7.5. The pH is seldom above 8.0 in fen waters, and the highest pH values do not coincide with the highest calcium concentrations, for reasons explained in Chapter 12. However, while the major inorganic ions account for some of the diversity in fens (Figs 180, 181; Table 8), they are far from explaining it all.

FIG 180. pH plotted against log [Ca] for 384 bog and fen water samples, 1991–7. Solid black points, ombrotrophic bogs; black triangles, typical small-sedge rich-fens; crosses are southern English valley bogs; open circles are other poor-and rich-fen sites; those enclosing a small ‘o’ are open-water samples.

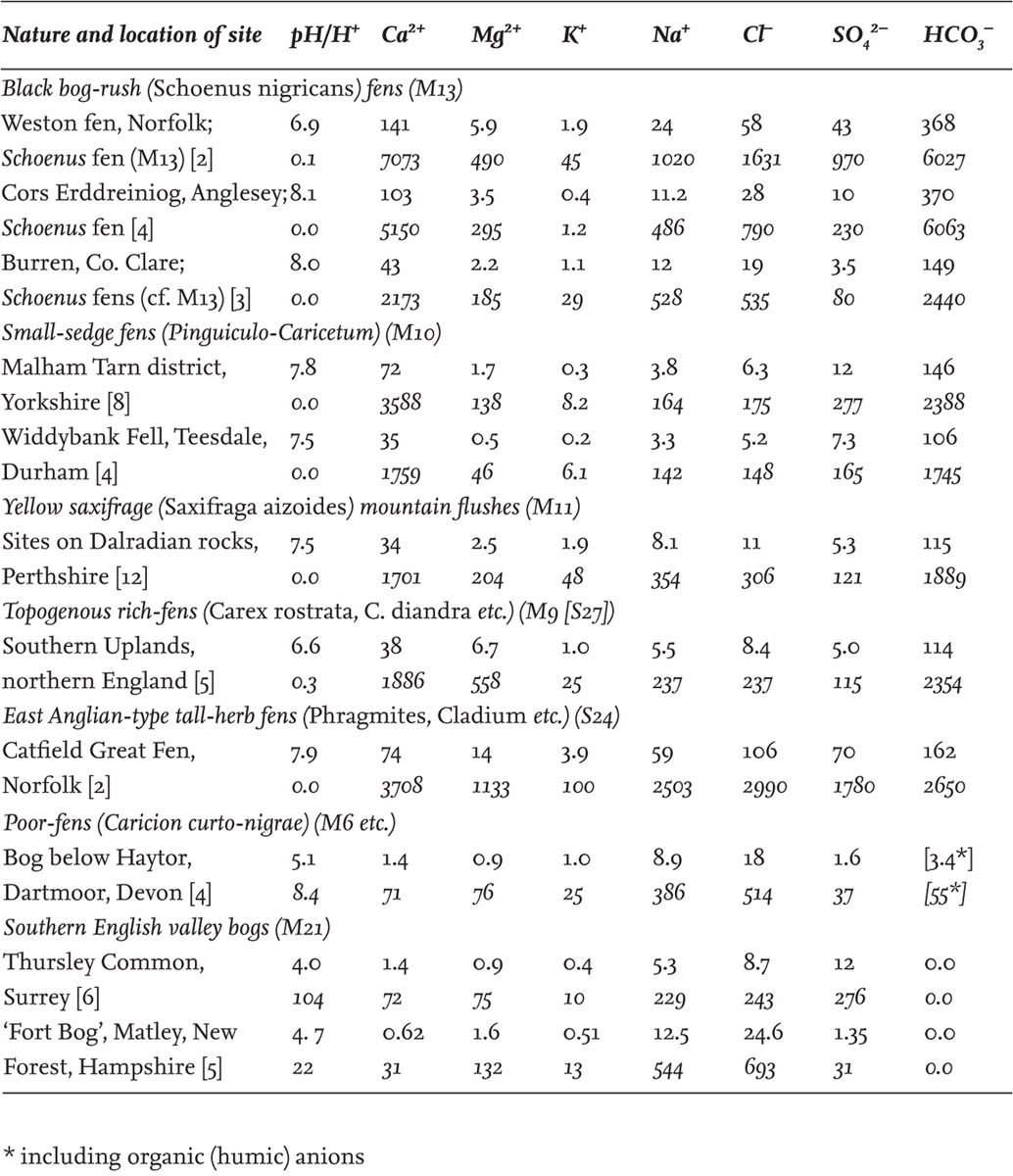

TABLE 8. Some representative averages from chemical analyses of fen waters in Britain and Ireland. Figures in roman type are mg/litre; figures in italics are µequiv/litre (µmol ionic charge/litre). Numbers of samples in square brackets [ ].

Much of the diversity in character of fens is related to the availability of the usual trio of major plant nutrients, nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K). At one extreme are fens, which may be highly calcareous, but are poor in other nutrients, especially phosphate. Their vegetation is generally short and open, and mosses are often prominent. With more N and P, the vegetation is taller but may still be rich in species. In heavily silted fen sites growth of a few bulky dominants may be so vigorous that it excludes all but a few other species. Chemical analysis of fen water samples rarely gives any indication of the availability of N and P to plants, because as soon as these limiting nutrients are released by decay of organic matter, they are immediately taken up again by plant roots or by microorganisms. However, peat contains abundant nitrogen combined in organic matter, and chemical analysis of peat can give an idea of the potential availability of N and P. What is important is the rate of ‘mineralisation’ of these limiting nutrients – their release in simple inorganic form, which plants can take up.

MAJOR TYPES OF FEN VEGETATION IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND: SPECIES COMPOSITION

Small-sedge rich-fens

Fens dominated by Schoenus nigricans are still widespread and common on the Carboniferous limestone of Ireland, and were formerly much more widespread than they are now on similar limestones in Anglesey, and on chalk and calcareous drift in East AngliaM13 (Fig. 182). Typically, Carex species are prominent, of which C. panicea, C. hostiana, C. viridula and sometimes C. nigra are the commonest and most conspicuous, along with a very characteristic range of associated species. Of these, common butterwort (Fig. 183a), grass-of-Parnassus (Fig. 183b), dioecious sedge (Fig. 184), few-flowered spike-rush (Eleocharis quinqueflora), lesser clubmoss (Selaginella selaginoides) and the mosses Campylium stellatum, Scorpidium scorpioides, S. revolvens and its close relative S. cossonii and the thalloid liverwort Aneura pinguis (Fig. 186e) are particularly characteristic of this kind of vegetation. Many other species occur including purple moor-grass (Molinia caerulea), quaking-grass (Briza media), marsh valerian (Valeriana dioica) and bog pimpernel (Anagallis tenella), and in the north of England bird’s-eye primrose (Primula farinosa). Fens of this kind provide a niche for a number of orchids, including early marsh-orchid (Dactylorhiza incarnata), marsh helleborine (Epipactis palustris, Fig. 300f) and fly orchid (Ophrys insectifera).

FIG 182. (a) Cors Erddreiniog, Anglesey, June 1990. A Schoenus-dominated rich-fen on Carboniferous limestone, with a rich calcareous fen flora. (b) Old peat cutting in Schoenus fen near Atyslany Lough, Co. Clare, September 1975. One of many such fens in the eastern Burren. Inflorescences of Schoenus and Molinia can be seen overhanging the water in the foreground.

Schoenus nigricans is a characteristic dominant of calcareous fens on the Continent. That pattern is repeated with us, but here Schoenus is mainly a lowland plant and at altitudes much above 300 m it is generally missing from rich-fen vegetation. Dominance then falls to the Carex species, and small-sedge fens of this kind are widespread and locally frequent, usually in small stands, on the Carboniferous limestone of the Pennines. These upland rich-fens are usually grazed by sheep or cattle, and often have a hummocky surface with grassland species on the tops of the hummocksM10. Similar communities occur very widely, usually in small patches, where lime-rich water seeps out to the surface and conditions are otherwise suitable. From Teesdale and the Lake District northwards, they pass into mountain flushes and fens with which they share many species, with the conspicuous addition of yellow saxifrage (Saxifraga aizoides) M11. These are dealt with in more detail in Chapter 17.

FIG 183. Plants of small-sedge fens: (a) common butterwort (Pinguicula vulgaris); (b) grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia palustris), Rinroe, near Corofin, Co. Clare, August 1958.

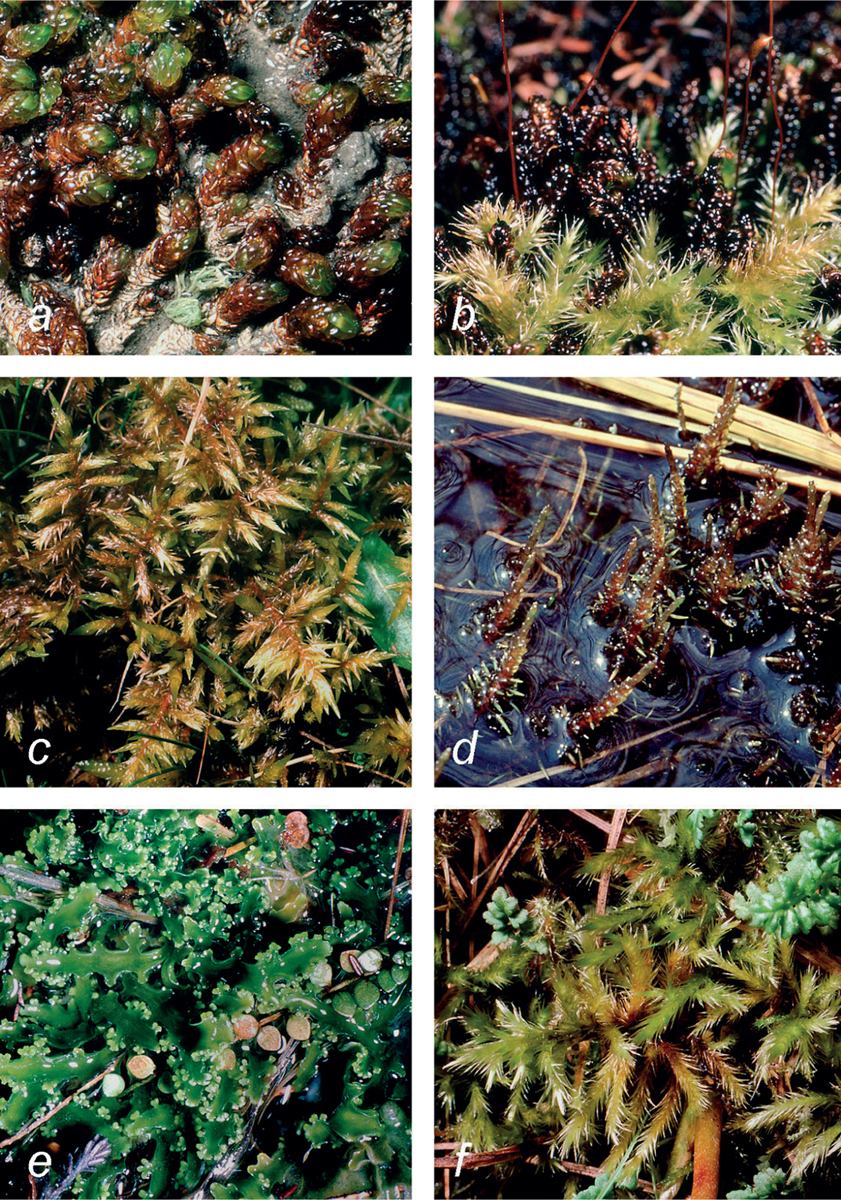

The communities just outlined are typically soligenous (‘soil-formed’); they are fed by springs, or more extensively where water seeps out at a spring-line on a slope. Where water accumulates in topographic hollows, or around shelving lake shores, calcareous fens occur at levels where the water-table is a few centimetres below the surface for much of the growing season. Such fens are topogenous (‘site-formed’). They share some species (and intergrade) with the soligenous rich-fens but they are different in character, and many of the most characteristic species of the typical small-sedge fens are rare or absent. They also intergrade with emergent-aquatic communities of neighbouring waters; sometimes (apart from water level) a ‘swamp’ and a ‘fen’ differ only in the presence of a continuous bryophyte layer and the denser and more species-rich vegetation of the latter. A common kind of wet fen over much of Britain and Ireland is dominated by various combinations of bottle sedge (Carex rostrata), lesser tussock-sedge (Fig. 185), carnation sedge (C. panicea), common sedge (C. nigra) and slender sedge (C. lasiocarpa), common cottongrass (Eriophorum angustifolium), marsh cinquefoil, bogbean, the horsetails Equisetum palustre and E. fluviatile, water mint (Mentha aquatica), marsh willowherb (Epilobium palustre), devil’s-bit scabious (Succisa pratensis), marsh-marigold (Caltha palustris), with an understorey of the mosses Calliergon giganteum, Calliergonella cuspidata, Scorpidium scorpioides and S. cossoniiM9 (Fig. 186). There are some very localised examples of essentially this community in otherwise Phragmites-dominated areas of the Norfolk Broads. A distinctive variant of this general kind of community, with Sphagnum teres and S. warnstorfii and often Tomenthypnum nitens (Fig. 186f)M8, occurs in the central Highlands of Scotland with fragmentary outliers in the Scottish borders, northern England and northern Mayo.

FIG 184. Dioecious sedge (Carex dioica), a very characteristic plant of the small-sedge fens. (a) Male plant, and (b) female plant in flower; both Gordale, Malham, Yorkshire, May 1984. (c) Female plant in fruit, Widdybank Fell, Teesdale, July 1978.

FIG 185. Lesser tussock-sedge (Carex diandra), Malham Tarn, Yorkshire, in wet topogenous fen with marsh cinquefoil (Potentilla palustris), bottle sedge (Carex rostrata) and bogbean (Menyanthes trifoliata)M9.

FIG 186. Rich-fen bryophytes: (a) Scorpidium scorpioides.; (b) S. revolvens (dark reddish brown, top) and Campylium stellatum (golden green, bottom); (c) Calliergonella cuspidata; (d) Calliergon giganteum; (e) the thalloid liverwort Aneura pinguis, with antheridial shoots; (f) Tomenthypnum nitens.

Several of the species in these wet fens tolerate an extraordinarily wide range of calcium concentration and pH, notably Carex rostrata, C. lasiocarpa and Menyanthes. We are in fact at the species-rich (and calcareous) end of a range of wet fens and swamps within which there are few clear divisions, and which are largely embraced within the alliances Caricion lasiocarpae and Caricion nigrae of Continental vegetation ecology. We shall encounter them again later.

Tall-sedge and tall-herb ‘fens’

These are the traditional ‘fens’ of East Anglia, and comparable (but usually more species-poor) vegetation elsewhere in England. They generally grow on peat with near-neutral pH, and in which nutrients are reasonably plentiful.

A purist would say they are not fens at all, but reedswamps perpetuated by centuries of reed cutting (Fig. 187). Around the Norfolk Broads, and locally elsewhere in East Anglia, the fen was the essential basis for a distinctive pattern of land use, providing peat for fuel, reed (Phragmites) and ‘sedge’ (Cladium) for thatching, ‘marsh hay’ (largely Calamagrostis canescens and Juncus subnodulosus with accompanying herbs) used as livestock feed, and litter (largely Molinia) for bedding livestock. This traditional pattern of usage created the Broadland fens as we know them, providing a mosaic of diverse and constantly renewed habitats underlying the biodiversity we have come to value. That biodiversity, long taken for granted by visiting naturalists, was an unintended by-product of years of labour dictated by the economics of past centuries (George 1992).

FIG 187. Tall-herb fenS24, Wicken Fen, Cambridgeshire, July 1981. Common reed dominant, with common meadow-rue (Thalictrum flavum), blunt-flowered rush (Juncus subnodulosus), yellow loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris), marsh bedstraw (Galium palustre) etc.

Left to itself, the fen would in due course become colonised by sallows and alder, and develop to fen carr or wet woodland. The maintenance of fen depends on cutting to prevent the growth of woody saplings. Cladium beds for thatching roof ridges were cut on a 3–4-year rotation. Managed reed-beds can be cut every year (in late autumn and winter), but this results in a significant drain of nutrients, and a better crop is obtained in the long run by cutting every other year. Marsh hay was cut annually from early summer to early autumn; litter was generally cut at the end of the growing season. Occasionally these areas were left uncut for a year or two.

Typical Broadland fen – the ‘Peucedano-Phragmitetum’ – is dominated by varying proportions of Phragmites, Cladium and Calamagrostis canescens. Accompanying these dominants is a very wide range of herbaceous plants, of which the commonest include marsh bedstraw, yellow loosestrife, milk-parsley (Fig. 188a, a rare species in England), hemp agrimony (Eupatorium cannabinum), purple-loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), blunt-flowered rush, meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria), water mint, common valerian (Valeriana officinalis), yellow iris (Iris pseudacorus), gypsywort (Lycopus europaeus), marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris), wild angelica (Angelica sylvestris), marsh thistle (Cirsium palustre) and water dock (Rumex hydrolapathum). A long list of mainly reedswamp plants occurs less frequentlyS24. This species-rich community has its headquarters in the Broads; it also occurs in a few other places in East Anglia (notably Wicken Fen, Fig. 187) and outlying sites in Somerset and east Yorkshire. Comparable Phragmites communities are widely scattered, but never as rich in species. A version with rather regular occurrence of hemp agrimony, marsh bedstraw, marsh thistle, wild angelica, blunt-flowered rush, water mint and purple-loosestrifeS25 occurs in the floodplains of calcareous rivers and similar sites scattered over England and Wales, and probably Ireland too. Much more widespread are species-poor reed-beds with few associated species apart from stinging nettle, cleavers (Galium aparine), great willowherb (Epilobium hirsutum) and, in the south and west, hemlock water-dropwort (Oenanthe crocata)S26.

FIG 188. (a) Milk-parsley (Peucedanum palustre), Catfield Fen, Norfolk, July 1997. (b) Great fen-sedge (Cladium mariscus), Sawston Meadows, Cambridgeshire, August 1984.

Fen meadows

In Broadland, marsh hay and litter were cut (more or less) annually from the ‘fen meadows’. After cutting, these usually served for grazing. In many parts of the country areas of fen were treated similarly, as part of the traditional agricultural landscape. Where the fen peat is base-rich these fen meadows are often very rich in species. Blunt-flowered rush is generally dominant, but such species as Yorkshire-fog (Holcus lanatus), tufted-sedge (Carex elata), yellow iris, carnation sedge, red fescue (Festuca rubra), creeping bent (Agrostis stolonifera), water mint, marsh thistle and meadow buttercup can locally have substantial cover, and much of the bulk of the herbage is made up of a variety of broad-leaved herbs. The community usually remains open enough for the moss Calliergonella cuspidata and marsh pennywort (Hydrocotyle vulgaris) to maintain a significant presenceM22.

In western parts of Britain and in Ireland two much commoner rushes, soft-rush (Juncus effusus) and sharp-flowered rush (J. acutiflorus), are prominent in a widespread wet-meadow (or wet-pasture) community on peaty soils that are acid and base-poor. Juncus effusus (sometimes replaced or accompanied by J. acutiflorus) is almost constantly present, along with Yorkshire-fog, marsh bedstraw and greater bird’s-foot trefoil. Other frequent species include marsh thistle, lesser spearwort (Ranunculus flammula), meadow buttercup (R. acris), tormentil (Potentilla erecta), meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria), sweet vernal-grass (Anthoxanthum odoratum), cuckooflower (Cardamine pratensis), marsh ragwort and common sorrel (Rumex acetosa)M23 (Fig. 189).

A third, rather distinctive, fen meadow is dominated by Molinia caerulea with constant or near-constant tormentil, devil’s-bit scabious, meadow thistle (Cirsium dissectum), greater bird’s-foot trefoil and carnation sedge, with frequent marsh thistle, wild angelica, flea sedge (Carex pulicaris) and tawny sedge (C. hostiana)M24. It tolerates some variation in calcium and pH, but probably favours sites rather low in phosphorus and nitrogen, which dry out somewhat in summer. This ‘Cirsio-Molinietum’ is widely distributed over southern Britain and Ireland. In eastern and central-southern England it generally occurs on rather base-rich peats or peaty mineral soils, reflected by the presence of some rich-fen or base-rich grassland species, such as fen bedstraw (Galium uliginosum), marsh valerian and common knapweed (Centaurea nigra). Farther west an essentially similar community grows on peaty gley soils in mildly calcareous patches on heaths, and more widely in rough pastures on the Culm Measures of west Devon and similar situations in south Wales and Ireland (Fig. 190). This lacks the more calcicole species of its eastern counterpart, but sharp-flowered rush, compact rush (Juncus conglomeratus), cross-leaved heath, marsh bedstraw and heath spotted-orchid (Dactylorhiza maculata) are frequentM24c. This community is a frequent habitat of lesser butterfly orchid (Fig. 191b) and the rare southwestern wavy St John’s-wort (Fig. 191a), which unaccountably seems to be absent from Ireland.

FIG 189. Rushy wet pastureM23, Hollow Moor, Devon, July 1994. Abundant soft-rush and Yorkshire-fog, with marsh ragwort (Senecio aquaticus), greater bird’s-foot trefoil (Lotus pedunculatus), marsh thistle (Cirsium palustre), whorled caraway (Carum verticillatum), etc.

FIG 190. Meadow-thistle (Cirsium dissectum)–purple moor-grass (Molinia caerulea) fen-meadowM24 on Carboniferous shales (Culm Measures), Witheridge Moor, Devon, June 1989.

FIG 191. Plants of heathy Molinia fen meadows: (a) wavy St John’s-wort (Hypericum undulatum), near Folly Gate, Devon, September 1985; (b) lesser butterfly orchid (Platanthera bifolia) amongst Molinia near Tubber, Co. Clare, July 1970.

These three ‘fen meadow’ types are relatively widespread, but there are more local variants. Wet ungrazed hollows almost anywhere, given a reasonable supply of nutrients, can grow up to dense stands of meadowsweet, often with wild angelica (Fig. 192). Few other plants are conspicuous, but soft-rush, creeping buttercup (Ranunculus repens), common sorrel (Rumex acetosa), marsh bedstraw, ragged-robin (Lychnis flos-cuculi), Yorkshire-fog and others often occur in smaller quantitiesM27. In principle, these meadowsweet–wild angelica stands could be replaced by wet woodland, and that would undoubtedly happen given time enough, but establishment of shrubs and trees is hindered by the density and profuse leaf-litter of the tall herbs. A distinctive northern fen meadow is much more local and has a different flavour from its southern counterparts, with abundant Molinia and common sedge (Carex nigra), frequent water avens (Geum rivale), and northern species such as marsh hawk’s-beard (Crepis paludosa) and globeflower (Trollius europaeus)M26.

FIG 192. Meadowsweet–wild angelica marshM27, Southmoor, near Folly Gate, Devon, September 1985.

Acid poor-fens

Poor-fens must surely be one of the Cinderellas of British plant ecology – those communities that are neither ombrogenous bogs nor ‘interesting’ floristically rich fens. Yet to neglect them is to leave out an important part of the mire scene, which has an interest and poses questions of its own.

Like the rich-fens, poor-fens may be roughly divided into those which occur mainly in pools or hollows or around lake shores (and in that sense are topogenous) and those which parallel the small-sedge rich-fens in that they occur on level or sloping ground wherever the soil or peat is wet enough (and in that sense are soligenous). The first group spans a continuous range from Carex–Sphagnum (‘Caricion lasiocarpae’) fens at the base-poor extreme to wet rich-fens at the other.

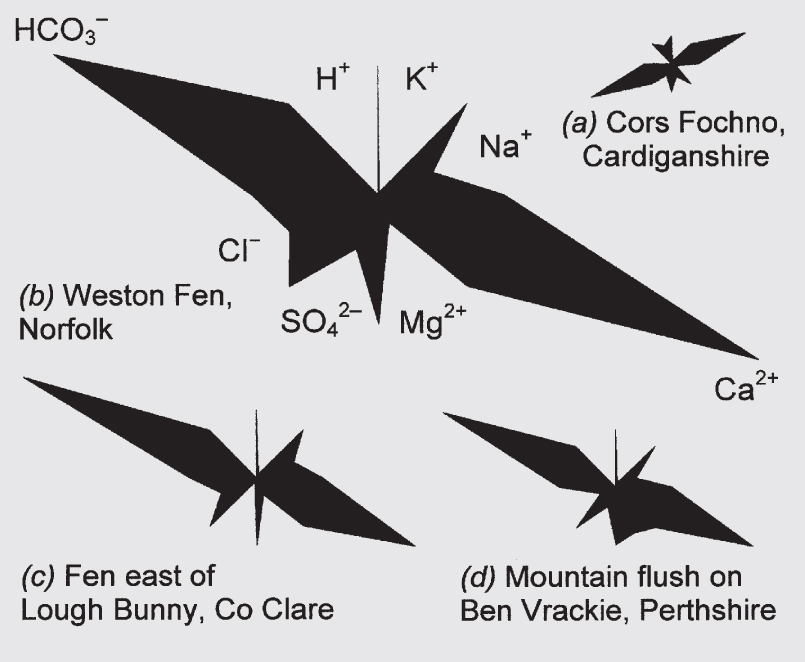

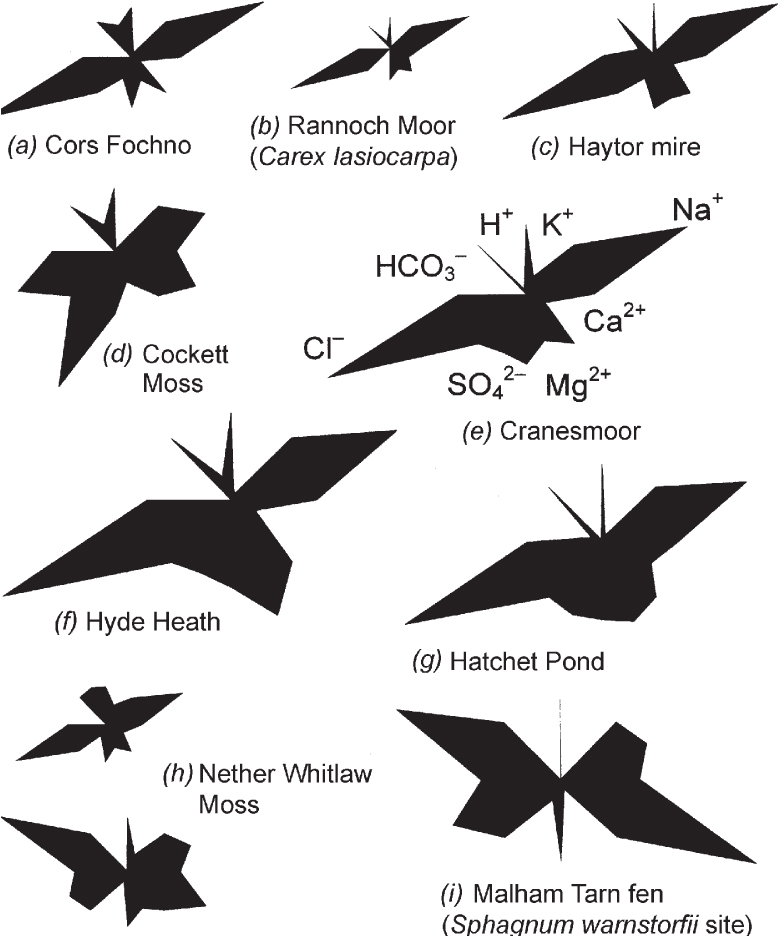

A number of prominent species of this first group have extremely wide tolerance of differences in water chemistry. The sedges Carex rostrata and C. lasiocarpa and bogbean are equally at home in blanket-bog pools in Sutherland and in calcareous fen in East Anglia or the Burren. Common cottongrass, bog-sedge (Carex limosa) and marsh cinquefoil have almost as wide an amplitude. This makes boundaries hard to draw, and to a large extent arbitrary – and yet there is a great deal of difference between the extremes. Figure 193 shows some Maucha diagrams from poor-fens (and from some transitional sites), with an ombrogenous bog for comparison. The Carex lasiocarpa poor-fen on Rannoch Moor (Fig. 193b) differs from neighbouring blanket bog only in its slightly higher pH, and somewhat higher calcium and magnesium levels. The valley mire near Haytor on the Dartmoor granite (Fig. 193c) has a higher pH and somewhat more magnesium and calcium than is usual in ombrogenous sites. Cockett Moss (Fig. 193d) is a Carex rostrata–Sphagnum fallax mireM4 near Settle, Yorkshire. It is almost as acid as Cors Fochno, and differs mainly in the higher concentrations of calcium and sulphate. At the more acid end of Nether Whitlaw Moss, near Selkirk (Fig. 193h, upper), the only sedges were Carex rostrata and Eriophorum angustifolium, over a moss-layer mainly of Sphagnum squarrosum; the water analysis differed from an ombrogenous bog principally in the higher values for potassium, calcium and magnesium. With greater mineral input, calcium and bicarbonate become the dominant ions and the vegetation is richer, with lesser tussock-sedge, marsh cinquefoil, ragged-robin and Sphagnum teres amongst other species (Fig. 193h, lower). A step on from this is Figure 193i from a Sphagnum-rich transitional-fen site (with S. teres and S. warnstorfii) at Malham Tarn; pH is up in the usual rich-fen range, and the preponderance of calcium and bicarbonate is more marked. In these last two sites, the flowering plants must draw their nutrients from the groundwater permeating the peat, but the bryophytes, raised above the water-table, will be largely dependent on rainwater and other airborne sources (and in that sense are ‘ombrotrophic’).

FIG 193. Maucha diagrams from a diversity of peatland sites. (a) Cors Fochno, Cardiganshire, an ombrotrophic bog; (b–d) poor-fens; (e–f) southern English ‘valley bogs’; (g–i) transitional sites between rich-fen and poor-fen. For further explanation see text, and Box 7.

The second group, the ‘Caricion nigrae’ small-sedge fens, are particularly associated with the old hard acid rocks of our uplands, where they are a constant part of the moorland scene, but they occur widely, if more sparsely, in wet heathy places elsewhere. A very variable community dominated by the rushes Juncus effusus and J. acutiflorus, common sedge, star sedge (Carex echinata), Polytrichum commune (our tallest moss), Sphagnum fallax, S. palustre and S. denticulatumM6 occupies seepages around springs or streams in moorland, or places where water drains from blanket peat. Sometimes these are virtually three-species stands of Juncus effusus, Polytrichum commune and Sphagnum fallax, especially in blanket-bog country. In more species-rich examples the sedges are typically prominent, along with tormentil, velvet bent (Agrostis canina), marsh violet (Viola palustris) and various species from surrounding communities. Numerous variants of this community have been recognised. The water chemistry of many examples of the Carex echinata–Sphagnum recurvum/denticulatum mire often shows little or nothing to distinguish them from ombrogenous bogs. At moderate altitudes white sedge (Carex curta) is often added to the mix, and becomes a regular component in the high-altitude Carex curta–Sphagnum russowii mire of the HighlandsM7.

Acid springs and seepages

Springs, issues of water on or at the foot of slopes, are much more prominent in the uplands (Chapter 17), but it is appropriate to say a few words about them here. A characteristic plant of neutral-to-acid springs is blinks (Fig. 194a), typically accompanied by mosses including Philonotis fontana, Sphagnum denticulatum, Warnstorfia exannulata, Calliergonella cuspidata and Dichodontium palustre and, rarely, Hamatocaulis vernicosus. In the mountains, starry saxifrage (Saxifraga stellaris) is a regular ingredient of this assemblageM32. At lower altitudes in western Britain it is replaced by a spring community with blinks, round-leaved crowfoot (Fig. 194b), lesser spearwort (Ranunculus flammula), bog pondweed (Potamogeton polygonifolius), bulbous rush (Juncus bulbosus) and the mosses Sphagnum denticulatum and Philonotis fontanaM35. This community would be expected in southern Ireland too. These southwestern springs tend to trail off into more extensive seepages, of a kind that often fringe moorland pools, with marsh St John’s-wort (Fig. 194c), bog pondweed, lesser spearwort, bulbous rush and Sphagnum denticulatumM29. This very characteristic community has a wide distribution from southern England and west Wales to Kerry and Mayo, and probably more widely than that.

FIG 194. Plants of springs, seepages and heathy pool margins: (a) blinks (Montia fontana), Creagan Meall Horn, Sutherland, June 1981; (b) round-leaved crowfoot (Ranunculus omiophyllus), Meldon, Devon, May 1991; (c) marsh St John’s-wort (Hypericum elodes), Burley, Hampshire, July 1989.

The southern English ‘valley bogs’

These, of which the best examples are in the New Forest (Fig. 195) and the Poole Harbour area of Dorset (Fig. 196), are a provoking exception to all the rules. Scandinavian ecologists would regard them as fens. Floristically, they belong with the ombrogenous bogs in the ‘Oxycocco-Sphagnetea’. Chemically (Fig. 193e, f), they share the preponderance of sodium and chloride with ombrotrophic bogs and other poor-fens, but mineral groundwater influence is betrayed by higher calcium, magnesium and potassium concentrations than could be accounted for by rainwater.

These valley bogs lie in a heathland landscape. Typically, dry heath with heather and bell heather grades down through a zone of wet heath, with cross-leaved heath, Sphagnum compactum and S. tenellum and scattered tufts of deergrass (Trichophorum cespitosum), into the bog. This is most often dominated by Sphagnum papillosum, cross-leaved heath and common heather, with varying amounts of Molinia and almost always abundant bog asphodel. Almost always there are hummocks of the fine-leaved red Sphagnum rubellum, and usually wet hollows or pools with S. cuspidatum, S. denticulatum or in some places S. fallax, often with white beak-sedge (Rhynchospora alba). Sphagnum papillosum sometimes alternates with the similar-looking but deep wine-red S. magellanicum in the moss carpet. In the Dorset bogs but not in the New Forest wide lawns of the brownish S. pulchrum are the rule. Some minor components are very characteristic of the habitat. Round-leaved sundew dots the Sphagnum carpet almost everywhere; oblong-leaved sundew (much the more effective insect trap) is a plant of the pools, and runnels in the wet heath. A number of leafy liverworts grow amongst the Sphagnum, some relatively large (Odontoschima sphagni, Mylia anomala), some tiny (Cladopodiella fluitans, Cephalozia connivens, C. macrostachya, Kurzia pauciflora) but fascinating and beautiful objects with a hand-lens or microscope.

FIG 195. New Forest valley bogs. (a) Cranesmoor, May 1996. Pools and hummock with self-sown pine on the surrounding heath; notice the ‘bonsai’ pine on the nearest hummock. (b) ‘Fort Bog’, Matley, June 1996. Pool with oblong-leaved sundew (Drosera intermedia) at the water’s edge; the lighter red rosettes of round-leaved sundew (D. rotundifolia) dot the Sphagnum cushions farther from the water. Leaves of bog asphodel (Narthecium ossifragum), which is abundant here, are still only a few centimetres long, and inconspicuous.

FIG 196. Pools in valley bogM21 on Studland Heath, Dorset, May 1973. The previous year’s dead flowering stems of Molinia and the bleached leaves of bog asphodel are still conspicuous. Sphagnum pulchrum is dominant here (a rather local species), with S. papillosum and S. rubellum on the hummocks, and S. cuspidatum in the pools. The hummocks are often topped by grey lichens (Cladonia spp.).

Downslope, the valley bogs grade into other communities. In some places the open hummock-and-pool Sphagnum carpet becomes more uniform and increasingly hidden beneath Molinia. Sometimes the bog grades into a strip of wet birch or alder carr in the valley bottom, with or without a zone of Molinia in between. These valley-bog–carr transitions can be exceedingly wet! In other places the bog becomes obviously more base-rich from the edge to the centre, as at Cranesmoor (and other places) in the New Forest and Hartland Moor in Dorset, marked by an abundance of Schoenus at both places. A subtler indication of base-rich influence (Fig. 197) is the occurrence of the pale butterwort and (more rarely) the bog orchid in the Sphagnum around bog pools, or in S. denticulatum-dominated seepages on the heaths.

Figure 193g is from a mildly calcareous seepage on heathland in the New Forest; a pH of 5.08 and 3.38 mg/litre of calcium are just enough to support the calcicole bog pimpernel and the mosses Scorpidium scorpioides and S. revolvens. In Devon and Cornwall Schoenus nigricans occurs very locally in characteristic (but variable) heathy flushes that straddle the dividing line between wet-heath and rich-fen, with Schoenus, Molinia, cross-leaved heath, bog asphodel, many-stalked spike-rush (Eleocharis multicaulis), bog pimpernel, the two wet-heath sundews, Sphagnum subnitens, S. denticulatum and varying quantities of the mosses Campylium stellatum, Scorpidium scorpioides and S. revolvensM14.

FIG 197. Two uncommon poor-fen species widely distributed in western Britain and Ireland, which find congenial habitats in southern English valley bogs: (a) bog orchid (Hammarbya paludosa), Hatchet Pond, New Forest, Hampshire, August 1970; (b) pale butterwort (Pinguicula lusitanica), Aylesbeare Common, Devon, July 1964.

Valley bogs were formerly widespread on the Surrey, Berkshire and north Hampshire heaths, but apart from Thursley Common near Godalming few now remain. Of the scattered small bogs across the Weald of Sussex and Kent, the best that remain are at Hothfield Common in Kent and Hurston Warren in Sussex. The most extensive lowland valley bogs outside Dorset, Hampshire and the southeast are Dersingham Bog and Roydon Common in northwest Norfolk, but some entirely characteristic small examples still exist in Devon.

Molinia, tussocky and otherwise

In central Europe, purple moor-grass (Molinia caerulea) is regarded as primarily a ‘fen meadow’ plant of peaty sites long managed by traditional farming – in short, as a plant of the ‘cultural landscape’. That may still be largely true in a broad sense in Britain and Ireland, but in the western parts of our islands Molinia attains a prominence unknown in central Europe. It occupies boggy valleys on heathland, fringes ombrogenous bogs, and dominates wide tracts of damp moorland. Molinia favours soils poor, but not extremely poor, in nutrients; it is tolerant of a wide range of soil moisture, calcium and pH. It does best in full light in the open, but tolerates partial shade. In heaths, valley bogs and on dried-out peatlands Molinia is favoured by disturbance and the high atmospheric nitrogen deposition in populated or intensively farmed areas.

Molinia is often an uncompromising dominant; few other plants may be in evidence apart from tormentil and sharp-flowered rushM25. In wet ground it is often tussocky, as anyone who has taken a short-cut across a damp valley in the New Forest will be uncomfortably aware. ‘Molinieta’ with us tend to fall into three categories. Close scrutiny may reveal a considerable range of bog or poor-fen species, such as cross-leaved heath, common cottongrass, bog-myrtle (Myrica gale – this may be conspicuous among the Molinia tussocks), various species of Sphagnum and the mosses Polytrichum commune and Aulacomnium palustreM25a. This boggy molinietum is often very tussocky. Molinia often dominates hill pastures on damp slopes. These are usually less tussocky, and the associated species reflect the surrounding acid grassland and its associated poor-fen communities, with such species as sweet vernal-grass, Yorkshire-fog, common bent (Agrostis capillaris), heath wood-rush (Luzula multiflora), soft-rush, marsh violet, marsh thistle and devil’s-bit scabiousM25b. A third category has something of the flavour of the Cirsio-Molinietum fen meadow but is dominated by dense tall Molinia, often tussocky, typically with scattered wild angelica and often hemp agrimony standing out above the Molinia canopyM25c; devil’s-bit scabious, greater bird’s-foot trefoil and a wide range of other species may occur in small quantities.

THE WATER SOURCE SOFFENS

Fen sites can be bewilderingly complex. It is easy to say that fens receive their water and solutes from two sources, rain and water that has drained through mineral ground – but, as ever, ‘the devil is in the detail.’ The influx of mineral-rich water may be seasonal, as in floodplain or lake-shore fens that regularly flood in winter; flooding is usually accompanied by deposition of mineral-rich (and often nutrient-rich) silt alongside the river or stream channel. For most of the year (and often all the year), streams that run through fens drain water from the fen, rather than bring nutrients into it. Water from mineral ground may be surface run-off, or water that has percolated deep into the soil or bedrock to emerge at springs, or more diffusely, at a spring-line or seepage zone where the water-table in a porous bedrock (aquifer) meets the surface – a classic situation for a soligenous fen (or valley bog). On more massive rocks, such as Carboniferous limestone, springs are usually more localised. Water from calcareous springs is often saturated with calcium bicarbonate at a far higher carbon dioxide concentration than the air. The surplus is deposited as calcium carbonate, and phosphate in the water is co-precipitated as insoluble calcium phosphate with it. Consequently, spring-fed calcareous rich-fens are typically nutrient-poor. Springs may be marginal to fens, or artesian within them. A vigorous spring may support active peat growth all around it but prevent plant growth actually over the spring, leading to ‘well-eyes’ in the fen. Suffice it to say that bogs and fens are not simple; their possible hydrological complexities are legion.

HOW ‘NATURAL’ ARE OUR FENS?

Many of our fens are clearly part of the cultural landscape in that they owe their present state to traditional land use by man since he first began clearing the forest and farming some 5000 years ago. The beautiful and species-rich north fen at Malham Tarn appears on an estate map of the 1780s as a group of named meadows, ‘Moss meadow’, ‘Long Meadow’ and so on, and the area was evidently in active agricultural use. Encroachment of sallow scrub has been an increasing problem in the 60 years since the Field Studies Council took over the site. Most of the East Anglian tall-herb Phragmites fens, left to themselves, would in a few decades revert to wet woodland, first of sallow and in course of time to alder and ash. This is the problem of fen management almost everywhere, except in the wettest places, or in sites still open to grazing. Are any of our lowland fens naturally open and treeless? That is a question we probably cannot answer with certainty. Tree growth is very slow in some rich-fen peats, perhaps owing to phosphate deficiency. Seedlings of pine and oak are frequent in the New Forest valley bogs, but the oaks never become established and pines that do so are slow-growing and stunted (Fig. 195a). On the other hand there would have been wild herbivores – red and roe deer, elk, aurochs, wild boar, beavers – before forest clearance by man began, so there were probably openings in the forest where physical conditions were less conducive to tree growth. There are indications that some rich-fen sites have been in essentially continuous existence since the early Post-glacial (perhaps often in mire-complexes that included ombrogenous bogs), and this is consistent with evidence from peat stratigraphy and pollen analysis. A few of the larger southern valley bogs could be comparably old (and might have had local ombrotrophy in their history), but many are probably of recent origin, and some formerly open sites are now wet woodland. The balance of evidence is that most of the present extent of lowland fen is a product of human activity.