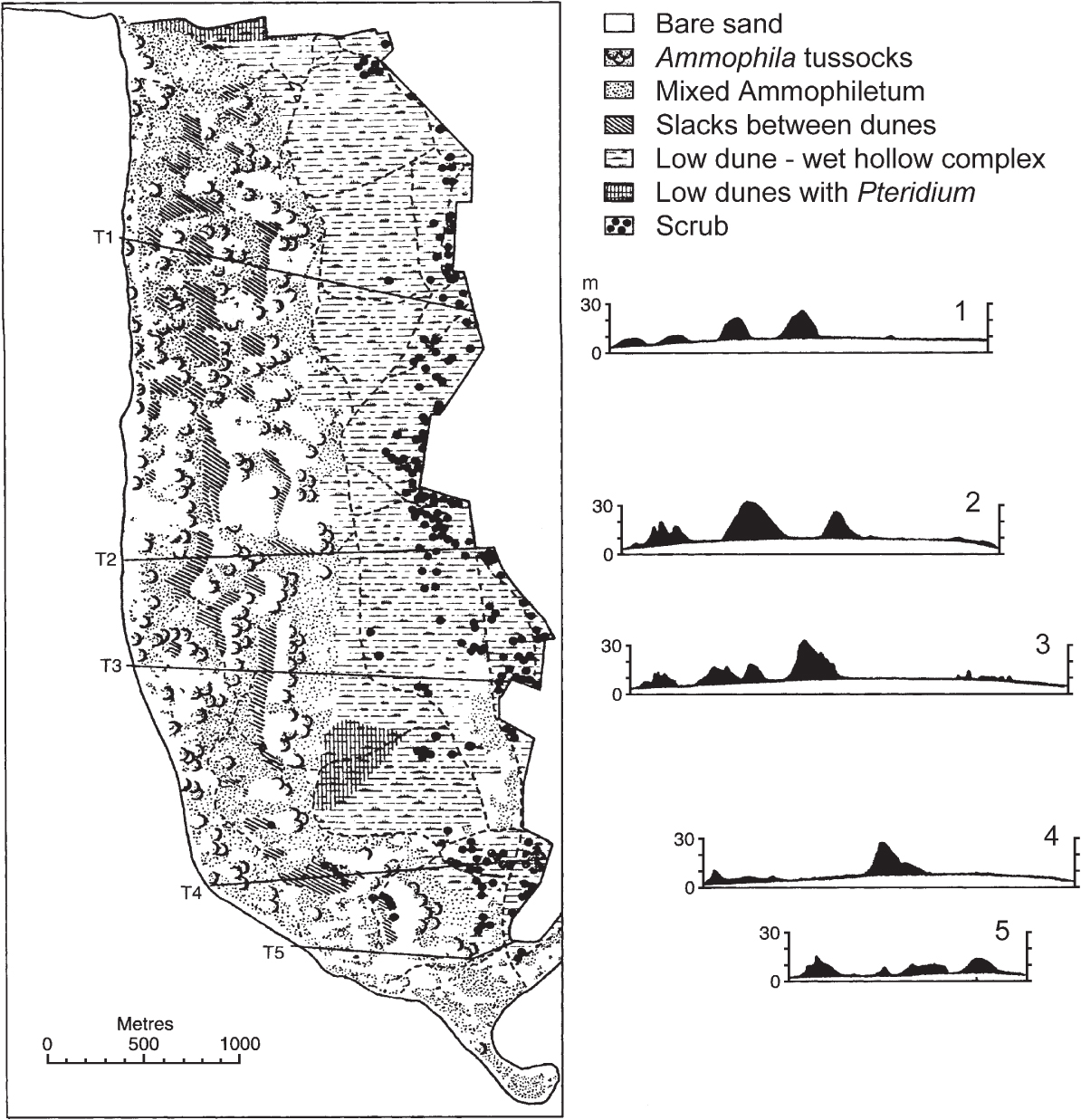

FIG 290. The dune system at Braunton Burrows, Devon, with levelled profiles across the dunes. The domed water-table is shown in white; the freely drained sand of the dune ridges above it in black. Compiled from Willis et al. (1959).

SALTMARSH IS ONE ACCRETIONAL HABITAT; sand-dunes and shingle are the other two. Sand-dunes occur all round our coasts. The only long segments of coastline without dunes are stretches of unbroken steep cliff, or unbroken wet muddy foreshore; even modest breaks in the continuity of a cliffed coast provide toeholds for small dunes to build up. Shingle beaches often fringe cliffed coasts, but the shingle is often not derived from the cliffs behind them. More distinctive (and often vegetationally more interesting) shingle features are much more local, and generally their shingle has clearly been carried by wave and current action from elsewhere. Nevertheless, sea-cliffs, dune and saltmarsh coexist in close proximity in many places.

For a dune system to develop, three things are necessary. The first is a source of sand on the foreshore – a wide sandy beach, sometimes the sandy shore of an estuary, which the local tides and currents keep replenished with sand. The second is at least reasonably frequent onshore winds – which do not have to be the prevailing winds, as shown by the numerous dune systems on our east and north coasts. The third is space to develop. That space may be landwards, as at Braunton Burrows (Fig. 290), Newborough Warren (Fig. 291) and many other west-coast ‘backshore’ dune systems, seawards over an accreting beach or ‘ness’, as at Tentsmuir, laterally along the shore or over a growing shingle spit or offshore island. In some places, dunes have overwhelmed farmland and settlements in historic times, as at Culbin and Forvie on the east coast of Scotland.

FIG 290. The dune system at Braunton Burrows, Devon, with levelled profiles across the dunes. The domed water-table is shown in white; the freely drained sand of the dune ridges above it in black. Compiled from Willis et al. (1959).

The highest strand-line left after the winter storms is made up of seaweed, dead crabs and the odd dead bird and all sorts of flotsam and jetsam. It includes also seeds of the strand-line plants, which germinate in spring, and flower and fruit from midsummer onwards. They are a limited but very characteristic assemblage – prickly saltwort (Salsola kali), sea rocket (Cakile maritima), Babington’s orache (Atriplex glabriuscula), frosted orache (Atriplex laciniata) and often the common weedy spear-leaved orache (Atriplex prostrata) (Fig. 291a). These are all annuals, but they are commonly joined by two perennials inseparable from the early stages of dune formation, sand couch (Elytrigia juncea) and sea sandwort (Honckenya peploides)SD2. This strand-line community provides the nuclei for embryo dunes to develop. Sand couch can withstand occasional immersion in seawater, but once it is firmly established it can build up substantial foredunes a metre or so high, and out of reach of the tidesSD4 (Fig. 291b). The only other species at all frequent on these foredunes are Cakile and Honckenya, along with a thin scatter of strand-line annuals, and pioneer plants of species, like sea-holly (Eryngium maritimum), more typical of the high marram dunes. Sand couch cannot withstand burial under more than 15–20 cm of sand, and cannot sustain indefinite upward growth, but it raises the foredunes to a level where the more vigorous dune-building grasses, marram (Ammophila arenaria) and lyme-grass (Leymus arenarius) can become established.

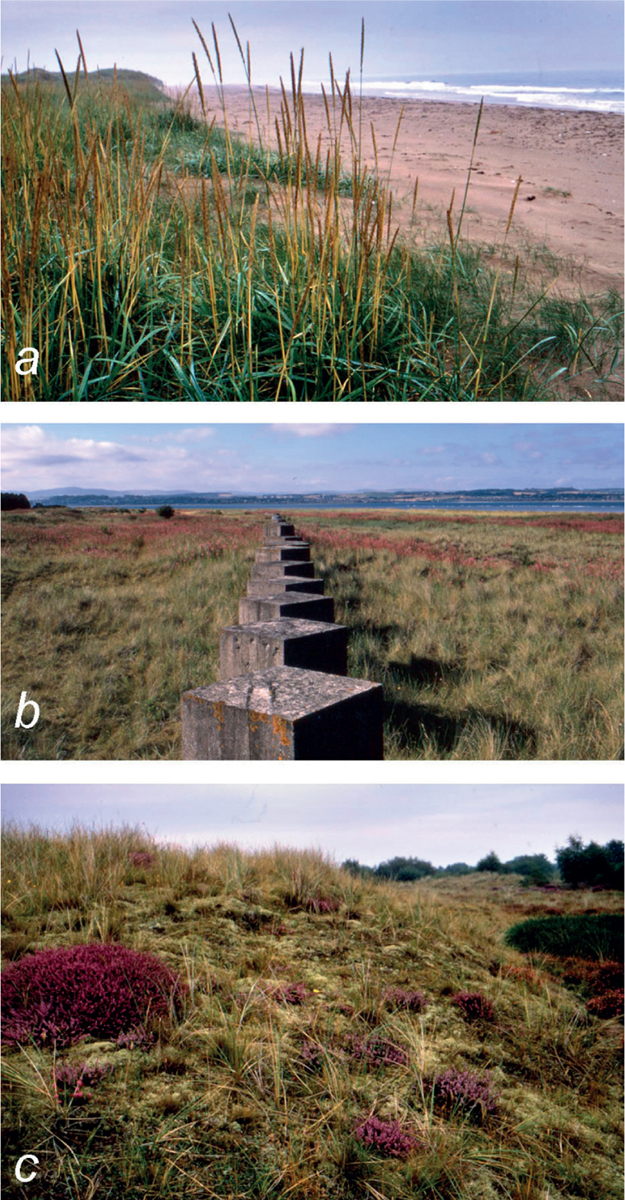

FIG 291. Newborough Warren, Anglesey. (a) Sea rocket–prickly saltwort–frosted orache strand-line community on the foreshore. In the middle distance sand couch is just beginning to colonise the strand-line, and to form a small embryo dune; the first ridge of high marram dunes to the left. (b) Embryo dune with sand couch.

Marram is intolerant of even brief immersion in seawater, but with its vigorous spreading growth it is very effective at intercepting and trapping blown sand; it can keep pace with burial under a metre or so of sand a year. Marram quickly builds up dunes 5 m or more high. Trapping of sand is most obvious on the lee side of individual marram tussocks; on the windward face an equilibrium is soon established between trapping of sand by the marram and its tendency either to be blown over the top or to slide downhill again (Fig. 292a). Behind the dune crest there is a modicum of shelter, and a great deal of eddying, and sand is deposited patchily, in drifts (Fig. 292b). The detailed physics of wind-transport of sand is quite complex; a good introduction is given by Packham & Willis (1997).

A dune ridge of any substantial height is liable to wind erosion of its windward side, the sand being carried over the crest of the dune and deposited on the lee side. Hence marram dunes tend to be mobile. Sometimes erosion gets the upper hand locally, often through disturbance, creating a blow-out. If this is extensive, it may initiate a ‘parabolic dune’ moving downwind at a few metres or tens of metres a year (Fig. 293). Aerial photographs show that this has been a common process on active west-coast dune systems such as Braunton Burrows and Newborough Warren. Parabolic dunes move apex-foremost (contrary to the unvegetated barchans of sandy deserts), their arms trailing back upwind; the whole system is commonly 100 m or so across. Erosion continues down to the level at which the sand is moist close to the water-table. Actively growing or mobile marram dunes generally leave a good deal of sand exposed; they have been called ‘yellow dunes’. A mobile ridge ceases its downwind travel as other ridges build up in front of it, erosion becomes less active, and the sand surface between the marram plants becomes vegetated and stabilised. The dune becomes ‘fixed’.

FIG 292. Mobile marram dune ridge at Newborough Warren. (a) Eroding windward face of dune; (b) Accreting sand in the lee of the dune crest.

FIG 293. Newborough Warren. A parabolic dune; the darker moist sand of a newly created slack can be seen in front of the eroding face, already being invaded by the mobile sand of the next dune ridge. May 1956.

The marram community is not rich in species, but three are frequent and particularly characteristic: sea-holly (Fig. 294a), sea bindweed (Fig. 294b) and sea spurge (Euphorbia paralias). These are all common on dunes from Norfolk to Galloway and all round the coast of Ireland; sea-holly extends up the east coast to Northumberland, and sea bindweed reaches Tayside, the southern Hebrides and Orkney. From the Isle of Wight westwards, these three are generally joined by Portland spurge (Euphorbia portlandica), which also grows on fixed dunes and in base-rich grassland near the sea. Beach sand is generally rich in nutrients from comminuted shells (Fig. 295) and strand-line debris, and the marram dunes are home to several common weeds, including ragwort (Senecio jacobaea), groundsel (S. vulgaris), creeping thistle (Cirsium arvense) and curled dock (Rumex crispus)SD6.

FIG 294. Plants of the mobile and semi-fixed dunes: (a) sea-holly (Eryngium maritimum); (b) sea bindweed (Calystegia soldanella); (c) dune pansy (Viola tricolor ssp. curtisii); (d) common restharrow (Ononis repens).

FIG 295. Newborough Warren. Sand on the foreshore contains a high proportion of broken-down seashells, and is highly calcareous.

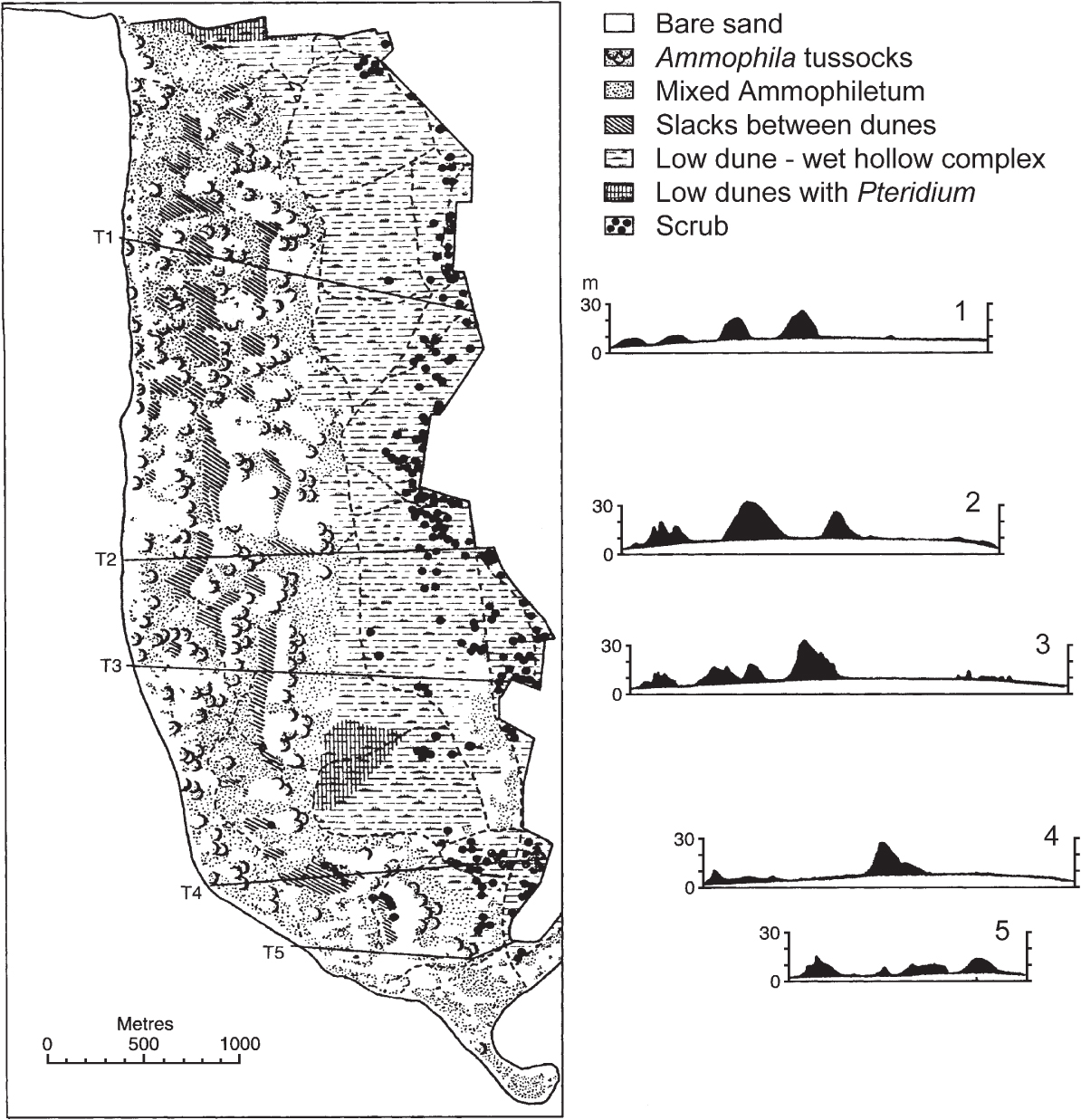

FIG 296. Tentsmuir dunes, Fife, September 1968. (a) Lyme-grass (Leymus arenarius) forming the first line of dunes; sand-couch embryo dunes can be seen on the foreshore below. (b) The dunes are growing seawards; this line of concrete blocks was placed along the shore-line in 1940 as an anti-invasion defence. (c) A ‘grey dune’. The sand has become leached and acid; the ground between the residual marram tufts is covered with grey lichens (Cladonia spp.), with scattered heather (Calluna) bushes.

Particularly on the east coast of both Britain and Ireland, marram is sometimes replaced as the main dune builder by lyme-grass (Fig. 296a), a handsome grass with flat leaves a centimetre or two wide, contrasting with the tightly rolled leaves of marram. Lyme-grass is a less effective sand binder than marram, and much less tolerant of burial by accumulating sand, so sand couch remains much more frequent than in the marram community; various weedy species occur occasionally, including perennial sow-thistle (Sonchus arvensis)SD5.

Water for the vegetation of dune ridges must come almost entirely from rain. Although marram can put down roots to 2 m, the groundwater-table is often some metres below that (the highest ridges on Braunton Burrows are 27 m above the water-table), and capillary rise in the sand above the water-table is seldom more than 50 cm. The sand of the dune ridges is sharply drained and contains less than 0.1% organic matter. Some water may come from dew on clear summer nights, but this is unlikely to exceed 0.4 mm a night. It has been suggested that water may move upwards as vapour with the reversed temperature gradient in the sand at night, but from the physics of the situation this is unlikely to be significant. In dry spells in summer the soil more than 50 cm above the water-table has a water content of less than 5% by weight; sand near the surface may contain only 1–2%, and is effectively air-dry. Under these conditions, marram is dependent on its deep root system to tap the little available water, and its ability to minimise water loss by rolling its leaves and closing its stomata. This it can do because its slender tall-growing leaves efficiently shed heat to the air, while the small plants in grazed fixed-dune turf must keep transpiring if they are not to get intolerably hot.

Once the surface of the sand between the marram clumps becomes reasonably stable, it can be colonised by smaller plants. The resulting semi-fixed dunes present a picture of bewildering variability in which the common factors are marram, red fescue (Festuca rubra) and forms of smooth meadow-grass (Poa pratensis sensu lato, probably mostly spreading meadow-grass, P. humilis); only slightly less constant than these is cat’s-ear (Hypochaeris radicata)SD7. A great diversity of other species may occur, and semi-fixed dunes can look extraordinarily different from one another; probably no two authors would agree on all the details of a workable classification (Fig. 297). Some of this variation may be due to differences in the nutrient status of the sand, some to its water-holding capacity or the proximity of the water-table, some to grazing and some to pure chance. The nitrogen-fixing legumes and lichens play a particularly crucial role in building up the nutrient capital of the soil. The commonest are bird’s-foot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus), common restharrow (Fig. 294d), hare’s-foot clover (Trifolium arvense, Fig. 324c) and white clover (Trifolium repens). Lichens of the genus Peltigera have cyanobacteria as their photosynthesising component, and these too can fix nitrogen.

FIG 297. Braunton Burrows, Devon. Semi-fixed dune with Syntrichia ruralis ssp. ruraliformis covering most of the ground between the remaining marram shoots. Scattered restharrow (Ononis repens), wild thyme (Thymus polytrichus), biting stonecrop (Sedum acre) and sparse red fescue. A leaf rosette of ragwort and a flower spike and several young rosettes of viper’s-bugloss (Echium vulgare) can be seen.

North of the Scottish border, cat’s-ear, dandelions, ragwort and sand sedge (Carex arenaria), mouse-ear hawkweed (Pilosella officinarum), lady’s bedstraw (Galium verum) and mosses (especially Hypnum cupressiforme sensu lato, Brachythecium albicans and Syntrichia (Tortula) ruralis ssp. ruraliformis) are prominent on many semi-fixed dunes. In the rest of Britain and Ireland, a very widespread and distinctive community is dominated by extensive carpets of Syntrichia ruralis ssp. ruraliformis, with common restharrow, dune pansy (Fig. 294c), bird’s-foot trefoil, lady’s bedstraw, wild thyme (Thymus polytrichus), lesser hawkbit (Leontodon saxatilis), mouse-ear hawkweed and mosses such as Hypnum lacunosum and Homalothecium lutescens. This seems better regarded as a (transitional) semi-fixed dune, rather than a dune grassland. Often in the same dune system transitions can be found that are more direct, containing little but marram with an understorey of red fescue and Poa humilis. There is a great deal of point-to-point variation in this general kind of vegetation, in which a nice range of small annuals find niches in early summer, including thyme-leaved sandwort (Arenaria serpyllifolia), sand cat’s-tail (Phleum arenarium) and dune fescue (Vulpia fasciculata)SD19.

Most dune systems have more or less extensive expanses of fixed-dune grassland on the still-calcareous sand behind the mobile dunes (Fig. 298). These grasslands are variable, but as a whole they are a remarkably species-rich habitat. They are generally dominated by red fescue, forming a close turf which is usually grazed. Lady’s bedstraw, ribwort plantain (Plantago lanceolata), white clover, bird’s-foot trefoil and Poa humilis are constant or nearly so, and such widespread grassland plants as common mouse-ear (Cerastium fontanum), ragwort, daisy (Bellis perennis), meadow buttercup (Ranunculus acris), yarrow (Achillea millefolium) and the moss Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus are commonSD8. A conspicuous and characteristic plant where it occurs is burnet rose (Rosa pimpinellifolia), low bushes of neat foliage borne on bristly-spiny stems, with white flowers followed by globular maroon rosehips. In the more northerly parts of our area ragwort, eyebright (Euphrasia officinalis agg.), Yorkshire-fog (Holcus lanatus), fairy flax (Linum catharticum), harebell (Campanula rotundifolia), self-heal (Prunella vulgaris), red clover (Trifolium pratense), glaucous sedge (Carex flacca), autumn gentian (Gentianella amarella), lesser meadow-rue (Thalictrum minus) and the mosses Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus and Pseudoscleropodium purum are somewhat more prominent than elsewhere. Much of the machair of the Hebrides and northwestern Ireland is grassland broadly of this kind. In fixed dune (machair) on the shell-rich sands of the Burren and the west Galway coast squinancywort (Asperula cynanchica) and the calcicole moss Homalothecium lutescens can play a prominent role.

FIG 298. Braunton Burrows, Devon. Undulating fixed-dune grassland, with residual tufts of marram, damp hollows and some scrub growth in the middle distance. May 1967.

Rain falling on a sand-dune system percolates into the sand to the water-table, which, if the dune system is essentially flat, will be gently domed (recall the ‘hydrological dome’ of the ombrogenous bogs of Chapter 15). A series of profiles across Braunton Burrows in North Devon is shown in Figure 290. The water-table is at about 3.5 m above mean sea level in the foredunes and in the boundary drain dividing the dunes from Braunton Marsh landwards, and about 10 m above sea level in the centre of the dunes – varying by around a metre in the course of the year. What is also clear from the profiles is that the mobile dune ridges stand high (up to c. 20 m) above the water-table. In simple terms, we can visualise the dune system as composed of mobile dunes marching downwind over a domed surface of damp sand; the areas of damp sand are dune slacks. In reality, it is not quite as simple as this. The water-table fluctuates, erosion is localised depending on the topography of the dunes at the time, and weather is capricious, so the level of the slacks is not strictly uniform. Parts of the slacks are under water for several months every winter, parts for a week or two at times of high flooding and parts (‘dry slacks’) are obviously related to the level of the water-table but never flood at all. Thus the dune-slack habitat is very variable, and correspondingly species-rich.

Dune slacks have in common the availability of water. If the sand on the foreshore contains a good proportion of shelly material, the water in the slacks will be calcareous. But because of the porous substratum the water-table fluctuates through the year in a rather different manner to that in many rich-fens (Chapter 14), and more akin to what happens in flood-meadows and the Irish turloughs. Probably the most universally distributed dune-slack plants are creeping bent and spreading meadow-grass. But the most conspicuous really common dune-slack plant is undoubtedly creeping willow (Fig. 299a). Other very widespread species include marsh pennywort (Fig. 299b), sand sedge, glaucous sedge, silverweed (Potentilla anserina), bog pimpernel, water mint (Mentha aquatica), self-heal (Prunella vulgaris) and the moss Calliergonella cuspidata.

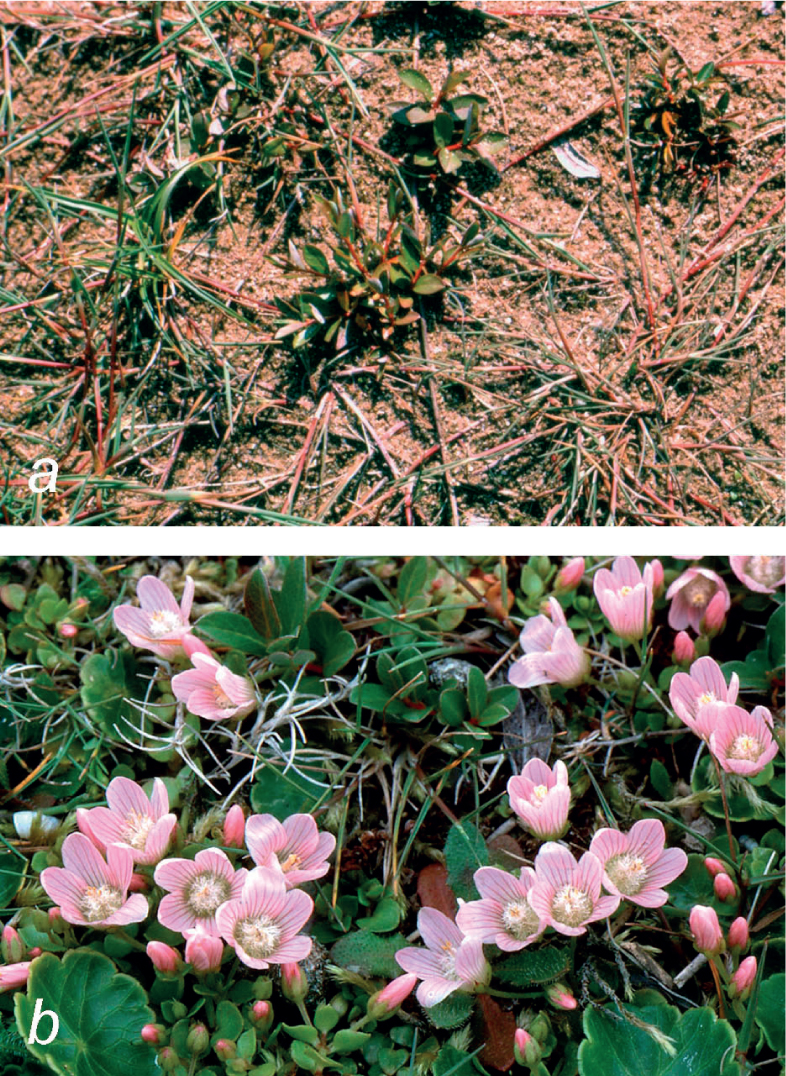

Dune-slack communities are as bewilderingly diverse as semi-fixed dunes, but they can perhaps be broadly divided into five groups. Rather open slacks with only a low and patchy growth of creeping willow are probably in general at an early stage in development with growth limited by meagre nutrient supply. They have a patchy grass cover, largely of creeping bent, but often support extensive carpets of bryophytes. Creeping willow, knotted pearlwort (Sagina nodosa) and the moss Bryum pseudotriquetrum are constant; sand sedge, jointed rush (Juncus articulatus) and the thalloid liverwort Aneura pinguis are also constant or nearly soSD13. This is the habitat of a number of rare bryophytes, including the mosses Amblyodon dealbatus, Bryum marattii and B. calophyllum, and the thalloid liverworts Moerckia hibernica and Petalophyllum ralfsii (Fig. 300a), from Devon to the machair of northwest Ireland and the Hebrides.

FIG 299. Dune-slack colonists. (a) Young plants of creeping bent (Agrostis stolonifera), creeping willow (Salix repens) and sand sedge (Carex arenaria) newly established from seed on the damp sand at the foot of an eroding mobile dune. (b) A later stage in colonisation: bog pimpernel (Anagallis tenella), creeping bent, creeping willow and marsh pennywort (Hydrocotyle vulgaris) have formed a closed turf.

FIG 300. Dune-slack plants: (a) the liverwort Petalophyllum ralfsii (rosettes c. 1 cm across, November); (b) brookweed (Samolus valerandi); (c) round-leaved wintergreen (Pyrola rotundifolia); (d) early marsh-orchid (Dactylorhiza incarnata ssp. coccinea); (e) fen orchid (Liparis loeselii); (f) marsh helleborine (Epipactis palustris). All at Braunton Burrows, north Devon.

In the Salix repens–Campylium stellatum communitySD14 the vegetation cover is much more nearly closed, with a bushy carpet of creeping willow, ankle-deep or rather more, usually with an extensive understorey of mosses. This is a very species-rich community. Creeping willow and the moss Campylium stellatum are constant; other constant or near-constant species are marsh pennywort, glaucous sedge, creeping bent, water mint, marsh helleborine (Fig. 300f), variegated horsetail (Equisetum variegatum) and the moss Calliergonella cuspidata. Sand sedge, autumn hawkbit (Leontodon autumnalis), lesser spearwort (Ranunculus flammula), dewberry (Rubus caesius), bird’s-foot trefoil and jointed rush are frequent. This is the dune slack that comes nearest to the rich-fens, with which it shares such species as carnation sedge (Carex panicea), water mint, lesser spearwort, bog pimpernel, grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia palustris, Fig. 183b), few-flowered spike-rush (Eleocharis quinqueflora), marsh bedstraw (Galium palustre), the moss Campylium stellatum and the thalloid liverwort Aneura pinguis. The occurrence of silverweed, creeping buttercup (Ranunculus repens), common sedge (Carex nigra), water germander and the mosses Drepanocladus sendtneri and Pseudocalliergon lycopodioides in this community at Braunton Burrows point to an affinity with some of the Burren turloughs in Co. Clare. This community is home to a number of other rarities, including impressive clumps of sharp rush (Juncus acutus), round-leaved wintergreen (Fig. 300c) and, more rarely, coralroot (Corallorhiza trifida) and fen orchid (Fig. 300e).

Much dune-slack vegetation dominated by creeping willow is less rich than this. The Salix repens–Calliergonella cuspidata dune-slack communitySD15 inclines more in the direction of a fen meadow than a rich-fen. Marsh helleborine is much less common, and the rich-fen moss Campylium stellatum and the calcicole liverworts that occur in the last community are scarce or absent; sharp rush and round-leaved wintergreen still occur but are less frequent. Conversely, silverweed, creeping buttercup, common sedge, greater bird’s-foot trefoil (Lotus pedunculatus) and hemp agrimony (Eupatorium cannabinum) are rather more prominent here.

Older and drier slacks are often occupied by a community dominated by a bushy growth of creeping willow knee-high or more with abundant Yorkshire-fogSD16. Apart from the two dominants, the most frequent species are red fescue, bird’s-foot trefoil and glaucous sedge; sand sedge, common restharrow, spreading meadow-grass and self-heal are also frequent, with a long list of associated species of low constancy and cover. This community has much more the character of a grassy creeping-willow scrub than the last two.

FIG 301. Braunton Burrows, Devon. Old creeping willow (Salix repens) slack, still partly flooded in early May 1969. Grey sallow (Salix cinerea) bushes in the foreground.

Some slacks and dune hollows are occupied by a community of grasses and sedges, especially creeping bent and common sedge, with abundant silverweed, but little or no creeping willowSD17. Also frequent are marsh pennywort, lesser spearwort, red fescue, cuckooflower (Cardamine pratensis), common spike-rush (Eleocharis palustris), creeping buttercup, Yorkshire-fog, spreading meadow-grass, marsh bedstraw and the moss Calliergonella cuspidata. Vegetation of this kind can probably be found on most dune systems, but it becomes progressively more important northwards, and damp hollows in the machair of the Hebrides are very much of this character, intergrading with the surrounding fixed-dune grassland.

Old dune slacks become colonised by sallow (Fig. 301) and locally, as at Braunton Burrows and Bull Island in Dublin Bay, by alder, forming damp scrubby vegetation and potentially wet woodland.

The importance of leguminous plants – clovers, vetches, common restharrow, etc. – in fixing nitrogen has already been mentioned in this book. Some other species have symbiotic nitrogen-fixing microorganisms associated with their roots, including alder, but most notably in a sand-dune context the thorny deciduous suckering shrub sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides). Sea buckthorn is regarded as native on the east coast of England, and widely introduced elsewhere (Pearson & Rogers 1962). On the east coast it usually grows as patches of scrub forming a mosaic with fixed-dune graslandsSD18. The lower and more open patches retain a rather impoverished fixed-dune flora dominated by red fescue, but this is shaded out under denser and more mature Hippophae and replaced by a sparse weedy vegetation including stinging nettle, false oat-grass (Arrhenatherum elatius), cleavers (Galium aparine), bittersweet (Solanum dulcamara), spear thistle (Cirsium vulgare) and elder. Sea buckthorn can become established early in the dune succession (Fig. 302) and has been widely planted to stabilise dunes. At some sites it can be an invasive pest, and it is generally regarded with disfavour (and exterminated) by those responsible for managing species-rich west-coast dunes where it is not native.

Sand sedge is very common in coastal dunes, especially round the edges of slacks, where the seeds germinate in the damp sand and the rhizomes run up the sides of neighbouring bare dunes marking their progress with conspicuous straight lines of green shoots (Fig. 303). Less conspicuously, sand sedge is often a widespread minor component of dune-slack communities, but very seldom dominates more than small patches of dune vegetation. However, in East Anglia inland dunes are developed locally on the ‘cover-sands’, notably in the Breckland between Mildenhall, Bury St Edmunds and Thetford. Sand sedge is dominant on these dunes (some of them 50 km from the sea), with a sparse associated flora in which only sheep’s fescue (Festuca ovina), ragwort, common mouse-ear, sheep’s sorrel (Rumex acetosella) and a few other common grassland species are frequentSD10.

FIG 302. Sea buckthorn colonising foredunes. Murlough dunes, near Newcastle, Co. Down, June 1991.

FIG 303. Sand sedge has long creeping rhizomes, which throw up leafy shoots at intervals. Here it is growing up the bare sand face of a mobile dune from the moist sand of a new dune slack where the seeds germinate.

The beach sand on many west coasts contains a high proportion of calcium carbonate from broken sea-shells, locally supplemented by fragments of the calcareous red seaweeds Corallina and Lithothamnion. Indeed, in some places the bleached remains of Lithothamnion make up most of the beach (‘coral strands’: Fig. 304). The constant high winds on exposed western coasts militate against the development of high marram dunes, so that broad expanses of fixed-dune pasture develop, with a flattish surface a bit above the water-table, traditionally called by the Gaelic word machair (literally a plain or field). The machair provides the only cultivable ground in many far-western places. The persistent winds carry a constant top-dressing of calcareous sand across the machair, often for several kilometres back from the shore. This counterbalances the constant leaching by rain, so that the fixed dunes and machair remain calcareous even in an oceanic climate wet enough to leach most terrestrial soils to heath or blanket bog. Machair is best developed on the Hebridean islands (Fig. 305a), but also occurs widely on the western Scottish mainland and on the western and northern coasts of Ireland (Dargie 1998, Gaynor 2006). For good aerial views of machair in the Western Isles see Friend (2012).

FIG 304. Lithothamnion shingle from a ‘coral strand’ near Carraroe, Co. Galway. The coin (an Irish shilling) is 23 mm in diameter.

FIG 305. Machair. (a) An expanse of machair on Benbecula, Western Isles. The grassland in the foreground is well-drained, with abundant bird’s-foot trefoil and ribwort plantain in flower, but there are often damper areas in machair as well, which add to its floristic diversity (© Lorne Gill/Scottish Natural Heritage). (b) The back of the Fanore dunes, Co. Clare, the southernmost machair in Ireland, July 1971.

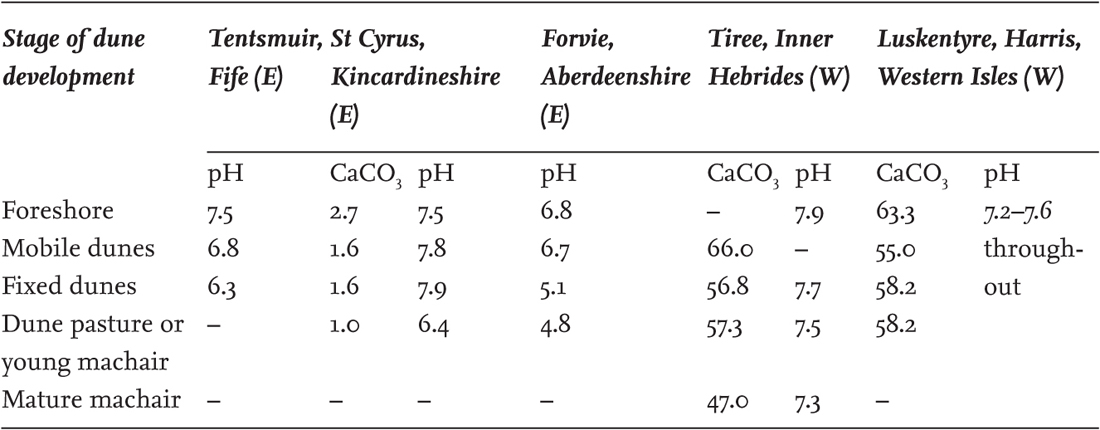

However, some dunes, especially on the east coast of Britain, are built up from sand containing little shelly material. Table 12 illustrates the contrast between Scottish west-coast and east-coast dunes. Not only is the calcium carbonate (CaCO3) content of the beach sand on the east coast much lower, but the fixed dunes become decalcified and acid, and ultimately bear dry Calluna–Empetrum ‘dune heaths’, which have no parallel on the west coast. The contrast between west- and east-coast dunes is nothing like as dramatic in southern Britain or Ireland as in Scotland. Most of the drainage of the Highlands is eastward, and rivers such as the Tay, Dee and Spey bring down an immense burden of sediment from largely non-calcareous mountain country; the major rivers of England and Ireland drain predominantly from limestone and soft-rock catchments. Nevertheless the effects of progressive leaching are apparent on English east-coast, and some west-coast, dunes. Sir Edward Salisbury (1952) showed that the CaCO3 content of the dune soil at Southport, Lancashire, declines from over 6% in the foredunes to a little over 1% in dunes a century old, and to a fifth or a tenth of 1% in the course of two or three centuries, with a concomitant fall in pH from 8.2 to 5.5. At Blakeney Point in Norfolk, CaCO3 fell from an initial 0.42% in young dunes (with pH 8.2) to very low values and pH 6.3 in dunes probably about 235 years old. The mildly acid conditions on these semi-fixed and fixed dunes are reflected in the prominence of mosses and especially lichens, mostly of the genus CladoniaSD11. This has led to them being called ‘grey dunes’, and because many dunes in southeast England (and hence accessible from London or Cambridge!) are of this nature this is sometimes used as general term for fixed dunes – but as Salisbury remarks, ‘the appropriateness of the epithet “grey dune” is apt to vary from one locality to another.’

TABLE 12. Average characteristics of soils from some Scottish dunes. Condensed from Gimingham (1964). Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) as per cent dry weight of soil. E, east coast; W, west coast.

The well-known dunes of the South Haven Peninsula south of the entrance to Poole Harbour are a special case. They are largely made up of sand from the Bracklesham Beds, decalcified sands that underlie the surrounding heathland, either eroded in situ or brought by tidal currents from the neighbouring coastline. They have grown up to seaward of a narrow heathy promontory in the course of the last 400 years. The present freshwater lagoon of the ‘Little Sea’ originated not as a dune slack, but as a tidal inlet cut off by the growth of a new dune ridge in front of it during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. ‘Greenland Lake’, the wet slack-like depression down the middle of Dawlish Warren in Devon, has a similar but more recent origin, and there are other examples. The South Haven Peninsula dunes show remarkably rapid transitions from typical foreshore vegetation and marram dunes to the typical Ulex minor–Agrostis curtisii heathH3 of the heathland behind them.

Shingle occupies perhaps a third of our coastline. The greater part takes the form of fringing beaches, essentially steep foreshores washed by waves at every tide. Typically, there is a storm ridge high on the beach consisting of coarse shingle or pebbles washed up by the highest storm waves of the past season – or the past several seasons. The crest, above this, is the highest shingle thrown up by truly monumental storms. To seaward, the shingle is reshaped by the waves and currents of every tide, and often there is net movement of shingle along the shore, very obvious if groynes have been built. If there is an angle in the coast, as at the mouth of an estuary, the line of the fringing beach is often continued as a shingle spit. At the end of the spit, the shingle commonly turns abruptly landward as a hook; the spit may continue growth along the original line, leaving the back decorated with a succession of hooks. If the source of the shingle was in deep water and shingle has been driven shorewards by rising sea level, it may form an offshore shingle bar, which may later join up with the coast at one or both ends. If there is an abundant and continuing supply of shingle, successive ridges may build up to seaward of one another forming an apposition beach, as at Dungeness. These more elaborate shingle forms are concentrated where the average tidal range is no more than 3–4 m; greater tidal ranges than this generally favour wide sandy beaches and mud-flats.

Stability is the most important factor determining what will grow on shingle. The vagaries of tide, wind direction and weather can result in a single tide removing several metres of shingle; conversely shingle can at times build up rapidly over a short succession of tides. Consequently many fringing shingle beaches on exposed shores are too unstable for any vegetation to get established. At the level where the beach is disturbed only by winter storms and stable throughout the growing season, an open cover of annual plants can become established, akin to the strandline community on sandy beaches. It consists largely of oraches (Atriplex prostrata, A. glabriuscula, A. laciniata), and such species as prickly saltwort, sea sandwort and Ray’s knotgrass (Polygonum oxyspermum) with occasional ruderals such as cleavers. Sea rocket, so conspicuous on sandy beaches, is less common on shingle. If the shingle is generally stable for several years in succession, perennials can colonise. These are the conditions for some of the most characteristic shingle plants, including the distinctive seaside form of curled dock (Rumex crispus ssp. littoreus), yellow horned-poppy (Fig. 306), sea-kale (Fig. 307), sea beet (Beta vulgaris ssp. maritima), sea mayweed (Tripleurospermum maritimum), sea campion (Silene uniflora) and, much more locally, sea pea (Fig. 308). These are often accompanied by a sprinkling of common weeds, including ragwort, perennial sow-thistle, bittersweet, creeping thistle, sticky groundsel (Senecio viscosus), herb-robert (Geranium robertianum) and silverweedSD1. These distinctive plants do not necessarily grow together, and there are many well-vegetated shingle beaches on which the plant cover is dominated by curled dock, sea beet, sea mayweed and sea campion, and of these curled dock is the most ubiquitous. With increasing stability grasses begin take on a role. Three species in particular are important. Sea couch (Elytrigia atherica) is common where shingle abuts on saltmarsh or on sea-walls. Red fescue is perhaps most common on sandy shingle, sometimes in company with bird’s-foot trefoil, wild thyme and biting stonecrop (Sedum acre). False oat-grass can be seen as beginning a transition to more ‘normal’ grassland turf.

FIG 306. Yellow horned-poppy (Glaucium flavum), Slapton, Devon, August 1983.

FIG 307. Sea-kale (Crambe maritima) in fruit on shingle at Pagham, Sussex, August 1983.

Sea pea is only really common on the Suffolk coast, yellow horned-poppy and sea-kale are rare north of the Clyde and Forth and in the west and north of Ireland, and sea beet is rare in most of Scotland. Here the vegetation of shingle is dominated by sea mayweed, curled dock, Babington’s orache and Ray’s knotgrass with cleavers, chickweed (Stellaria media), couch-grass (Elytrigia repens) and silverweed among a group of weedy associates. This general kind of vegetationSD3 is the habitat of oysterplant (Mertensia maritima), a northern species that has become increasingly rare with us over the past century.

FIG 308. Sea pea (Lathyrus japonicus), Chesil Beach, Abbotsbury, Dorset, August 1972.

Clean, pure shingle is a virtually impossible habitat for plants to colonise. It has virtually no water-holding capacity after rain, and offers virtually no plant nutrients. At least some fine material amongst the shingle is essential for plant growth. On the face of it shingle is a dry habitat, and much has been written about the sources of water available to shingle plants. Shingle beaches have a freshwater-table beneath them, just as sand-dunes do, but unless this is near the surface even deep-rooted plants cannot reach it. It is well established that neither ordinary dew nor condensation of water vapour amongst the pebbles can contribute significantly to the water-budget of the vegetation. The conclusion has to be that shingle plants draw their water from the ‘soil’ in the normal way. Rain falls over the entire surface of the shingle and drains into it; the surface pebbles are an effective mulch, minimising evaporation. Typical shingle vegetation covers only a small fraction of the surface, so there is potentially a large supply to meet a relatively small demand.

Some nutrients come dissolved in rain (Chapter 15). The shingle traps wind-borne dust and sand. The churning of the waves at every tide acts as a pebble-grinder, so fine particles are constantly being produced, which weather, so producing mineral nutrients. Seabirds contribute their quota, most obviously around nesting colonies. Seaweed and other debris cast upon the shore contribute organic matter, nitrogen and phosphorus, and of course once plants becomes established their roots are an ongoing source of organic matter. The net result of all these processes is that the soil tends progressively to become more ‘normal’, so that what began as open (and very characteristic) shingle vegetation evolves gradually into a grassy turf, initially dominated by red fescue but later invaded by false oat-grass, cock’s-foot (Dactylis glomerata) and other grassland plantsMG1a[d,e].

These grasslands on stable shingle usually have a distinctly seaside character; the splendid dark-green rosettes of sea radish (Raphanus raphanistrum ssp. maritimus) are often a striking feature of them. The closed grassland loses water over its whole surface so, unlike the sparse pioneer shingle plants, it is often severely droughted in late summer. Sometimes bryophytes (e.g. Dicranum scoparium, Brachythecium albicans) and lichens (Xanthoria parietina, Cladonia spp.) are important colonisers of stable shingle, leading to a thin, acid species-poor Festuca–Agrostis grassland with sheep’s sorrel and annuals such as whitlowgrass (Erophila verna), early hair-grass (Aira praecox), stork’s-bill (Erodium cicutarium), dove’s-foot crane’s-bill (Geranium molle), bird’s-foot (Ornithopus perpusillus) and various annual clovers (Trifolium spp.). Succession on stable shingle can progress to scrub of gorse, bramble and blackthorn, and at some sites to woodland, but that takes us back to earlier chapters.

FIG 309. Foredunes with marram and cottonweed (Otanthus maritimus), Lady’s Island Lake, Co. Wexford, July 1970.

Most of the foregoing has been aimed at giving a general picture relevant to shingle beaches all round our coasts. However, so much attention has been concentrated on a few classic sites that we cannot close without saying something about them. More detail is given by Tansley (1939), Steers (1946) and Packham & Willis (1997). All of the sites are in Britain; Ireland seems to have less shingle development than its sister island, though there is extensive cobble-type shingle in Galway Bay and, as noted by Praeger (1934), ‘The SE coast of Ireland is characterised by great stretches of sand and gravel … From Bray Head in Wicklow down as far as Waterford stretch after stretch of shingle and sand extend … sometimes closing the mouths of inlets still or once marine, as at Lady’s Island Lake, Tacumshin Lake and Bannow Bar, all in Wexford.’ That stretch of coast in Wexford is well known as the only remaining Irish or British locality for cottonweed (Fig. 309). The south coast from Wexford to Cork is probably the richest in Ireland for shingle plants.

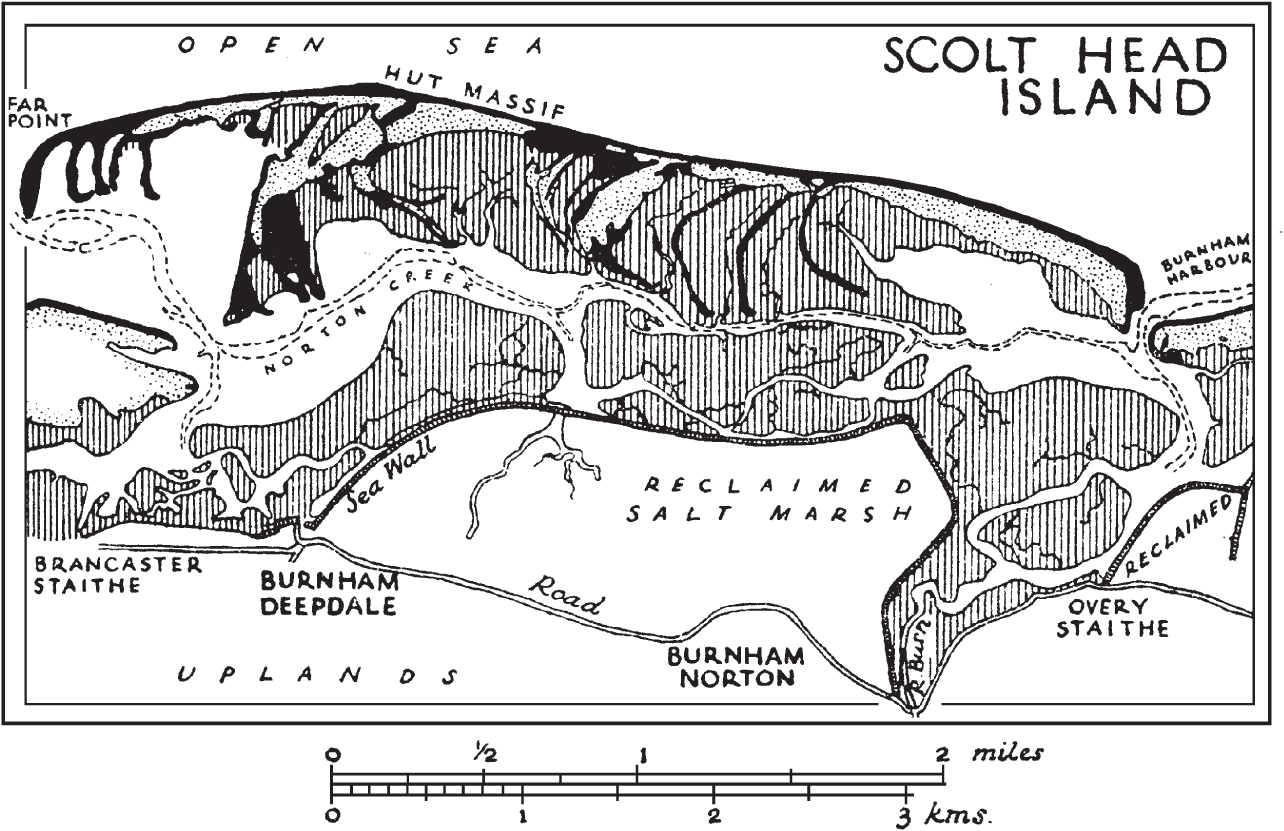

Blakeney Point is a complex shingle spit, about 6 km long, running in a west-northwest direction from the coast near Cley-next-the-Sea on the north Norfolk coast. The shingle provides the foundation on which extensive dunes have built up. There are saltmarshes between the hooks and broad expanses of saltmarsh along the coast facing the spit from Blakeney village westwards. Scolt Head Island (Figs 310, 311), some 20 km to the west, is essentially an offshore shingle bar that has grown by spit development westwards, leaving a succession of long curved hooks in its wake. There are some dunes, and extensive saltmarshes between the hooks, and fronting the mainland. Both sites combine good shingle and saltmarsh vegetation with dunes. Floristically they are notable for matted sea-lavender (Limonium bellidifolium) and the common occurrence of shrubby sea-blite (Suaeda vera) at the contact of saltmarsh and shingle, and for grey hair-grass (Corynephorus canescens) on the dunes.

FIG 310. Scolt Head Island (1925), a shingle-spit system on the coast of north-west Norfolk. The shore current runs from east to west and the growing tip is at the western end. The hook of the shingle spit (black) marked as ‘Far point’ is the most recent; the others preserve stages in the history of the spit. This coast changes in detail from year to year, but the main outlines remained much the same in 2010 as they were in 1925. Sand-dunes (stippled) overlie the broader expanses of shingle; saltmarshes (vertical hatching) have grown up on the tidal mud in the shelter of the shingle banks. From Tansley (1939), slightly amended; see also the more detailed maps of Blakeney Point (1946) and Scolt Head Island (1933) in Steers (1946).

This is a magnificent shingle spit, some 17 km long, separating the River Alde from the sea between Aldeburgh and its mouth at Shingle Street (Fig. 312). From Aldeburgh the shingle ridge starts narrow and straight a few degrees west of south. After a few kilometres a succession of old hooks can be discerned on the landward (river) side, but the seaward face remains almost straight to a point east of Orford village, where it swings southwest. This coincides with a broad section in which a close succession of hooks pass into apposition ridges before the spit settles into its new direction for another 5 km, finally following the curve of the coast to the mouth of the river. This stretch of the Suffolk coast has outstandingly rich shingle vegetation, and is notable as the headquarters in our area for sea pea, elsewhere thinly scattered round the British and Irish coasts.

FIG 311. The eastern end of Scolt Head Island, at the entrance to Burnham Harbour and Overy Staithe, showing vividly the distribution of shingle, sand-dunes and saltmarsh. Compare Fig. 310; since the 1920s and 1930s the shingle ridge has moved back making the coast straighter and encroaching on the dunes, and the saltmarsh has extended and matured (© Adrian Warren & Dae Sasitorn/www.lastrefuge.co.uk).

FIG 312. Orford Ness, a long and complex shingle spit extending for some 17 km south from Aldeburgh along the Suffolk coast, and enclosing the mouths of the Rivers Alde and Ore. Shingle Street is at the bottom of the picture (© Adrian Warren & Dae Sasitorn/ www.lastrefuge.co.uk).

The largest shingle spit in Europe, this is the classic example of an apposition beach, formed by successive deposition of ridges of shingle. It is suggested that it may have passed through a stage similar to Orford Ness, as an eastward-growing spit along the lower course of the River Rother, which then emerged to the sea east of New Romney (Fuller 1989). A breach in the shingle ridge near Rye changed accretion and erosion patterns, leading to the present-day cuspate foreland. Dungeness is not particularly notable for shingle vegetation as such (many sites on the Sussex coast are as good), but is fascinating for its diversity of habitat and richness in examples of succession on old shingle (Scott 1965), including scrub of gorse, brambles, blackthorn and elder, and the famous holly wood.

This is another site that would be famous even if nothing grew there. It starts as a fringing beach at Burton Bradstock, and leaves the low indented coastline just south of Abbotsbury (Figs 313, 314) to sweep in a smooth gentle curve to the Isle of Portland. It is a single ridge around 7–8 m high; the shingle grades in average size from less than 1 cm at Abbotsbury to 2–3 cm near Portland. Surprisingly, flints from the chalk make up a large proportion of the shingle, as they do at Slapton on the Devon coast (Fig. 315). The lagoon to landward of Chesil Beach, the Fleet, is open to the sea at its southern end. Shingle vegetation is largely confined to the back of the beach; the most prominent species are curled dock, sea beet and sea campion, but yellow horned-poppy, sea-kale and sea pea are there as well. Shrubby sea-blite forms an intermittent zone at the base of the shingle along the shore of the Fleet; high water in the Fleet is marked by a strandline of dead Zostera leaves, from the beds of Z. angustifolia growing in the quiet saline water. The brackish marsh at the Abbotsbury end of the Fleet (near the swannery) has marsh-mallow (Althaea officinalis) and divided sedge (Carex divisa). At the Portland end wild thyme carpets expanses of stabilised shingle.

FIG 313. Chesil Beach, Abbotsbury, Dorset, September 1981. Shingle vegetation dominated by curled dock (Rumex crispus ssp. littoreus), sea campion (Silene uniflora) and sea beet (Beta vulgaris ssp. maritima).

FIG 314. Chesil Beach, near Abbotsbury, Dorset, August 1972. Shrubby sea-blite (Suaeda vera) growing along the shoreline of the Fleet, at the back of the shingle ridge.

FIG 315. The shingle bar at Slapton Ley, Devon, from the south, May 1973. There is open shingle vegetation with yellow horned-poppy (Glaucium flavum) etc. between the crest of the shingle and the road; the backslope between the road and the freshwater Ley was formerly grazed by rabbits but is now rank grassland and scrub.