Chapter 8. Large Type, Kid Mode & Accessibility

If you were told that the iPhone was one of the easiest phones in the world for a disabled person to use, you might spew your coffee. The thing has almost no physical keys! How would a blind person use it? It’s a phone that rings! How would a deaf person use it?

But it’s true. Apple has gone to incredible lengths to make the iPhone usable for people with vision, hearing, or other physical impairments. As a handy side effect, these features also can be fantastically useful to people whose only impairment is being under 10 or over 40.

If you’re deaf, you can have the LED flash to get your attention. If you’re blind, you can turn the screen off and operate everything—read your email, surf the web, adjust settings, run apps—by letting the phone speak what you’re touching. It’s pretty amazing (and it doubles the battery life).

You can also magnify the screen, reverse black for white (for better-contrast reading), set up custom vibrations for each person who might call you, and convert stereo music to mono (great if you’re deaf in one ear).

The kiosk mode is great for kids; it prevents them from exiting whatever app they’re using. And if you have aging eyes, you might find the Large Text option handy. You may also be interested in using the LED flash, custom vibrations, and zooming.

Here’s a rundown of the accessibility options in iOS 10. To turn on any of the features described here, open Settings→General→Accessibility. (And don’t forget about Siri, described in Chapter 6. She may be the best friend a blind person’s phone ever had.)

Tip

You can turn many of the iPhone’s accessibility features on and off with a triple-click of the Home button. See Accessibility Shortcut for details.

VoiceOver

VoiceOver is a screen reader—software that makes the iPhone speak everything you touch. It’s a fairly important feature if you’re blind.

On the VoiceOver settings pane, tap the on/off switch to turn VoiceOver on. Because VoiceOver radically changes the way you control your phone, you get a warning to confirm that you know what you’re doing. If you proceed, you hear a female voice begin reading the names of the controls she sees on the screen. You can adjust the Speaking Rate of the synthesized voice.

There’s a lot to learn in VoiceOver mode, and practice makes perfect, but here’s the overview:

Touch something to hear it. Tap icons, words, even status icons at the top; as you go, the voice tells you what you’re tapping. “Messages.” “Calendar.” “Mail—14 new items.” “45 percent battery power.” You can tap the dots on the Home screen, and you’ll hear, “About This Book of 9.”

Once you’ve tapped a screen element, you can also flick your finger left or right—anywhere on the screen—to “walk” through everything on the screen, left to right, top to bottom.

Double-tap something to “tap” it. Ordinarily, you tap something on the screen to open it. But since single-tapping now means “speak this,” you need a new way to open everything. So: To open something you’ve just heard identified, double-tap anywhere on the screen. (You don’t have to wait for the voice to finish talking.)

Tip

Or do a split tap. Tap something to hear what it is—and with that finger still down, tap somewhere else with a different finger to open it.

There are all kinds of other special gestures in VoiceOver. Make the voice stop speaking with a two-finger tap; read everything, in sequence, from the top of the screen with a two-finger upward flick; scroll one page at a time with a three-finger flick up or down; go to the next or previous screen (Home, Stocks, and so on) with a three-finger flick left or right; and more.

Or try turning on Screen Curtain with a three-finger triple-tap; it blacks out the screen, giving you visual privacy as well as a heck of a battery boost. (Repeat to turn the screen back on.)

On the VoiceOver settings screen, you’ll find a wealth of options for using the iPhone sightlessly. For example:

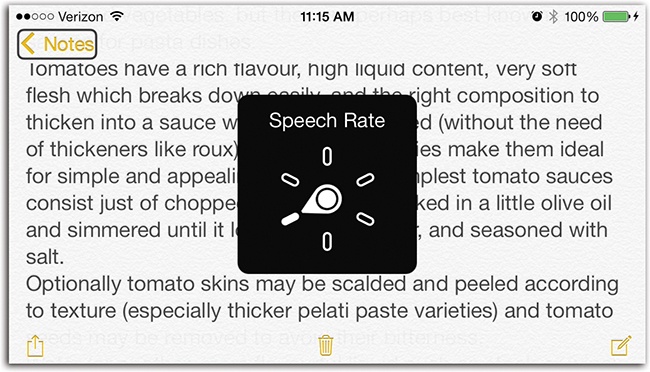

Speaking rate slider controls how fast VoiceOver speaks to you, on a scale of tortoise to hare.

Use Pitch Change makes the phone talk in a higher voice when you’re entering letters and a lower voice when you’re deleting them. It also uses a higher pitch when speaking the first item of a list and a lower one when speaking the last item. In both cases, this option is a great way to help you understand where you are in a list.

Verbosity makes the phone speak more to help you out more. For example, Speak Hints gives you additional suggestions for operating something you’ve tapped. For example, instead of just saying, “Safari,” it says, “Safari. Double-tap to open.” And Emoji Suffix makes the phone say (for example) “pizza emoji” instead of just “pizza” when encountering an emoji symbol.

Speech is where you choose a voice for VoiceOver’s speaking. If you have an iPhone 5s or later (with at least 900 megabytes of free space), you can install Alex, the realistic male voice that’s been happily chatting away on the Mac for years.

Here, too, is the new Pronunciation feature, which is described in How to De-Sparsify iOS 10’s Design. Finally, you can choose the language you want for the Rotor (Note).

Braille, of course, is the system that represents letters as combinations of dots on a six- or eight-cell grid. Blind people can read Braille by touching embossed paper with their fingers. But in iOS they can type in Braille, too. For many, that may be faster than trying to type on the onscreen keyboard, and more accurate than dictation.

On this Settings screen, you specify, among other things, whether you want to use the six- or eight-dot system.

When you’re ready to type, you use the Rotor (described in a moment) to choose Braille Screen Input, which is usually the last item on the list. If the phone is flat on a table (“desktop mode”), the six “keys” for typing Braille are arrayed in a loose, flattened V pattern.

If you’re holding the phone, you grip it with your pinkies and thumbs, with the screen facing away from you (“Screen away” mode).

Audio gives you three options. Use Sound Effects helps you navigate by adding little clicks and chirps as you scroll, tap, and so on. Audio Ducking makes music or video soundtracks get momentarily softer when the phone is speaking. And the new Auto-select Speaker in Call is ingenious: It switches the phone to the speakerphone automatically whenever you’re not holding it to your head.

The Rotor is a brilliant solution to a thorny problem. If you’re blind, how are you supposed to control how VoiceOver reads to you? Do you have to keep burrowing into Settings to change the volume, speaking speed, verbosity, and so on?

Nope. The Rotor is an imaginary dial. It appears when you twist two fingers on the screen as if you were turning an actual dial.

And what are the options on this dial? That’s up to you. Tap Rotor in the VoiceOver settings screen to get a list of choices: Characters, Words, Speech Rate, Volume, Punctuation, Zoom, and so on.

Once you’ve dialed up a setting, you can get VoiceOver to move from one item to another by flicking a finger up or down. For example, if you’ve chosen Volume from the Rotor, then you make the playback volume louder or quieter with each flick up or down. If you’ve chosen Zoom, then each flick adjusts the screen magnification.

The Rotor is especially important if you’re using the web. It lets you jump among web page elements like pictures, headings, links, text boxes, and so on. Use the Rotor to choose, for example, images—then you can flick up and down from one picture to the next on that page.

Typing Style. In Standard Typing, you drag your finger around the screen until VoiceOver speaks the key you want—and then simultaneously tap anywhere with a second finger to type the letter.

In Touch Typing, you can slide your finger around the keyboard until you hear the key you want; lift your finger to type that letter.

There’s also Direct Touch Typing, which is a faster method intended for people who are more confident about typing. If you tap a letter, you type it instantly. If you hold the key down, VoiceOver speaks its name but doesn’t type it, just to make sure you know where you are.

Phonetic Feedback refers to what VoiceOver says as you type or touch each keyboard letter. Character and Phonetics means that it says the letter’s name plus its pilot’s alphabet equivalent: “A—Alpha,” “B—Bravo,” “C—Charlie,” and so on. Phonetics Only says the pilot’s-alphabet word alone.

Typing Feedback governs how the phone helps you figure out what you’re typing. It can speak the individual letters you’re striking, the words you’ve completed, or both.

Modifier Keys. You can trigger some VoiceOver commands from a physical Bluetooth keyboard; all of them use Control-Option as the basis. (For example, Control-Option-A means “read all from the current position.” A complete list of these shortcuts is at http://j.mp/1kZRSOz).

The Modifier Keys option lets you use the Caps Lock key instead of the Control-Option business, which simplifies the keyboard shortcuts at least a little bit.

Always Speak Notifications makes the phone announce, with a spoken voice, when an alert or update message has appeared. (If you turn this off, then VoiceOver announces only incoming text messages.)

Navigate Images. As VoiceOver reads to you what’s on a web page, how do you want it to handle pictures? It can say nothing about them (Never), it can read their names (Always), or it can read their names and whatever hidden Descriptions savvy web designers have attached to them for the benefit of blind visitors.

Large Cursor fattens up the borders of the VoiceOver “cursor” (the box around whatever is highlighted) so you can see it better.

Double-tap Timeout lets you give yourself more time to complete a double-tap when you want to trigger some VoiceOver reading. Handy if you have motor difficulties.

VoiceOver and Braille input take practice and involve learning a lot of new techniques. If you need these features to use your iPhone, then visit the more complete guide at http://support.apple.com/kb/HT3598.

Or spend a few minutes (or weeks) at applevis.com, a website dedicated to helping the blind use Apple gear.

Tip

VoiceOver is especially great at reading your iBooks books out loud. Details are in Books That Read to You.

Zooming

Compared with a computer, an iPhone’s screen is pretty tiny. Every now and then, you might need a little help reading small text or inspecting those tiny graphics.

The Zoom command is just the ticket; it lets you magnify the screen whenever it’s convenient, up to 500 percent. Of course, at that point, the screen image is too big to fit the physical glass of the iPhone, so you need a way to scroll around on your virtual jumbo screen.

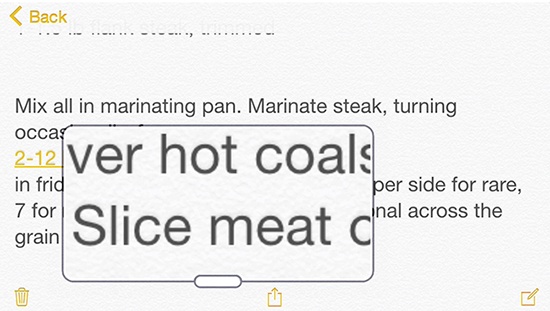

To begin, you have to turn on the master Zoom switch in Settings→General→Accessibility. Immediately, this magnifying lens appears:

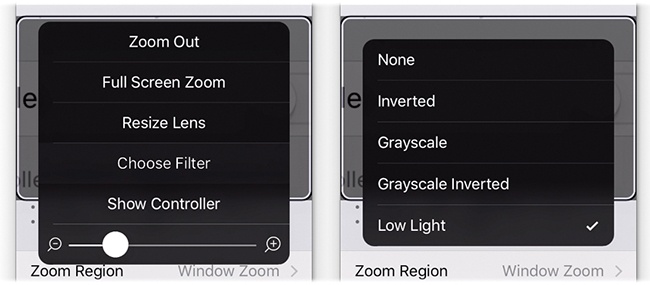

Scroll down and look at the Zoom Region control. If it’s set to Window Zoom, then zooming produces this movable rectangular magnifying lens. If it’s set to Full Screen Zoom, then zooming magnifies the entire screen. (And that, as many Apple Genius Bar employees can tell you, freaks out a lot of people who don’t know what’s happened.)

Now then. Next time you need to magnify things, do this:

Start zooming by double-tapping the screen with three fingers. You’ve either opened up the magnifying lens or magnified the entire screen. The magnification is 200 percent of original size. (Another method: Triple-press the Home button and then tap Zoom.)

Pan around inside the lens (or pan the entire virtual giant screen) by dragging with three fingers.

Zoom in more or less by double-tap/dragging with three fingers. It’s like double-tapping, except that you leave your fingers down on the second tap—and drag them upward to zoom in more (up to 500 percent) or down to zoom out again.

You can lift two of your three fingers after the dragging has begun. That way, it’s easier to see what you’re doing.

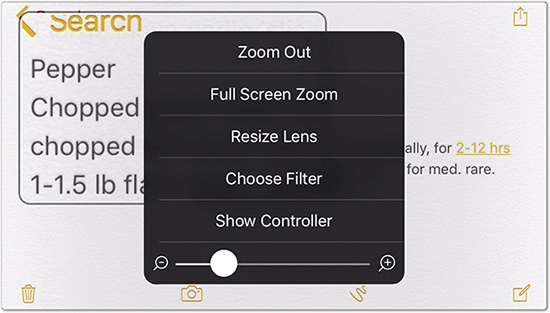

Open the Zoom menu by tapping the white handle on the magnifying lens. Up pops a black menu of choices like Zoom Out (puts away the lens and stops zooming), Full Screen Zoom (magnifies the entire screen, hides the lens), Resize Lens (adds handles so you can change the lens’s shape), Choose Filter (lets you make the area inside the lens grayscale or inverted colors, to help people with poor vision), and Show Controller (the little joystick described in a moment). There’s also a slider that controls the degree of magnification, which is pretty handy.

That’s the big-picture description of Zoom. But back in Settings→General→Accessibility→Zoom, a few more controls await:

Follow Focus. When this option is turned on, the image inside the magnifying lens scrolls automatically when you’re entering text. Your point of typing is always centered.

Smart Typing. When this option is turned on, a couple of things happen whenever the onscreen keyboard appears. First, you get full-screen zooming (instead of just the magnifying lens); second, the keyboard itself isn’t magnified, so you can see all the keys.

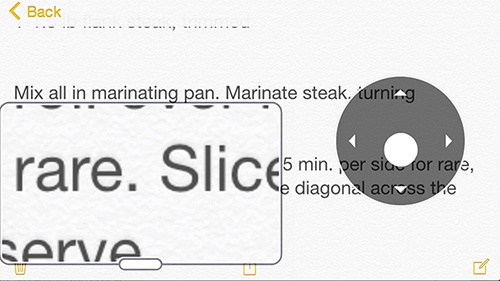

Show Controller. The controller is this weird little onscreen joystick:

You can drag it with your finger to move the magnifying lens, or the entire magnified screen, in any direction. (It grows when you’re touching it; the farther your finger moves from center, the faster the scrolling.) It’s an alternative to having to drag the magnified screen with three fingers, which isn’t precise and also blocks your view.

You can tap the center dot of the Controller to open the Zoom menu described already. Or double-tap the center dot to stop or start zooming.

Idle Visibility. After you’ve stopped using the joystick for a while, it stays on the screen but becomes partly transparent, to avoid blocking your view. This slider controls how transparent it gets.

Zoom Region controls whether you’re zooming the entire screen or just a window (that is, a magnifying lens).

Zoom Filter gives you options for how you want the text in the zoom window to appear—for example, black on gray for viewing in low light. (See the super-cool Zoom Filter tip in The Instant Screen-Dimming Trick.)

Maximum Zoom Level. This slider controls just how magnified that lens, or screen, can get.

Tip

When VoiceOver is turned on, three-finger tapping has its own meaning—“jump to top of screen.” Originally, therefore, you couldn’t use Zoom while VoiceOver was on.

You can these days, but you have to add an extra finger or tap for VoiceOver gestures. For example, ordinarily, double-tapping with three fingers makes VoiceOver stop talking, but since that’s the “zoom in” gesture, you must now triple-tap with three fingers to mute VoiceOver.

And what about VoiceOver’s existing triple/three gesture, which turns the screen off? If Zoom is turned on, you must now triple-tap with four fingers to turn the screen off.

Magnifier

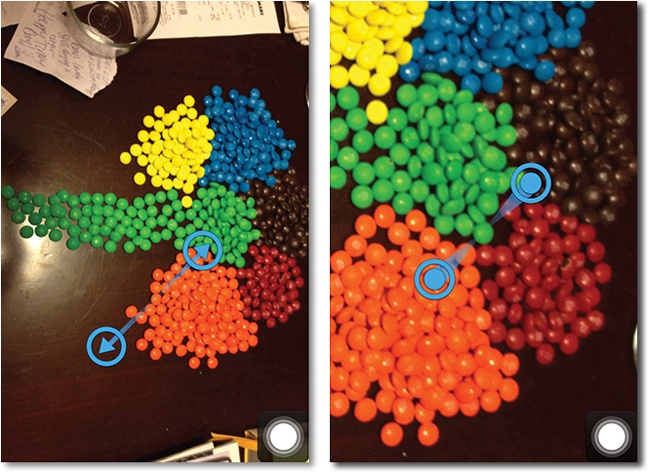

Oh man, this is great: In iOS 10, you can triple-click the Home button to turn the iPhone into the world’s best electronic magnifying glass. It’s perfect for dim restaurants, tiny type on pill bottles, and theater programs.

Once you’ve summoned the Magnifier, you can zoom in, turn on the flashlight, or tweak the contrast.

To set this up, open Settings→General→Accessibility→Magnifier. Turn on Magnifier. Turn on Auto-Brightness, too; it’ll help the picture look best.

Then, next time you need a magnifying glass, triple-click the Home button. Instantly, the top part of the screen becomes a zoomed-in view of whatever is in front of the camera.

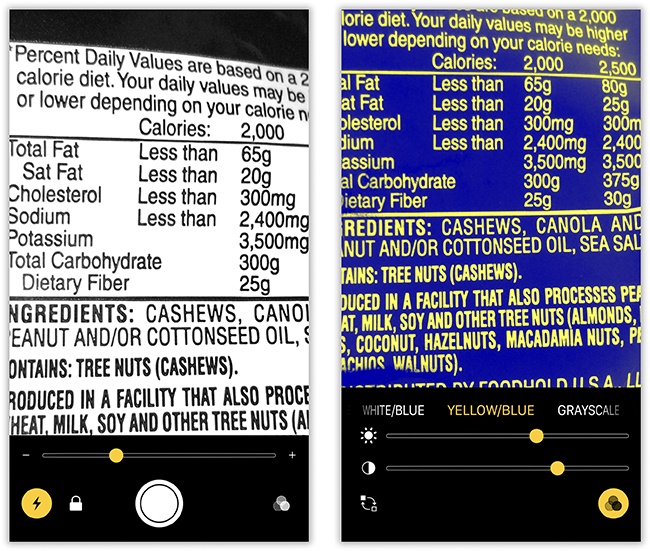

At this point, you gain a wealth of options for making that image even clearer (next page, left):

Zoom slider. Adjusts the degree of magnification.

. Locks the focus, so that the phone quits trying to refocus as you move the phone. (You can also tap the screen for this function.)

. Locks the focus, so that the phone quits trying to refocus as you move the phone. (You can also tap the screen for this function.)2. Freezes the frame. That way, once you’ve finally focused on what you want to read, you can actually read it, without your own hand jiggles ruining the view.

The Filters screen offers even more tools for making things clear:

Filter. Swipe horizontally across the screen (you don’t have to aim for the little row of filter names) to cycle among the Magnifier’s color filters: None, White/Blue, Yellow/Blue, Grayscale, Yellow/Black, Red/Black. Each may be helpful in a different circumstance to make your subject more legible.

and

and  sliders. Adjusts the brightness and contrast of the image.

sliders. Adjusts the brightness and contrast of the image. . Swaps the two filter colors (black for white, blue for yellow, and so on).

. Swaps the two filter colors (black for white, blue for yellow, and so on).

To exit the Filters screen, tap  again; to exit the Magnifier, press the Home button.

again; to exit the Magnifier, press the Home button.

Color Filters

This item, and some of the features in it, are new in iOS 10. They affect the color schemes of the entire screen, in hopes of making it easier for you to see.

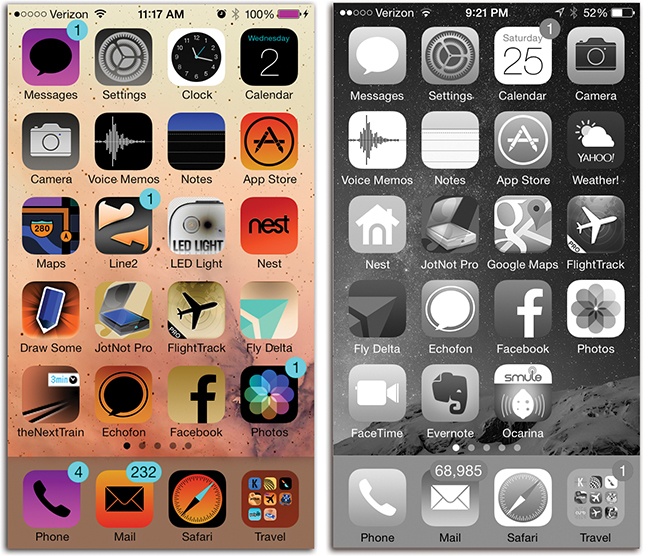

Invert Colors. By reversing the screen’s colors black for white, like a film negative, you create a higher-contrast effect that some people find is easier on the eyes (below, left). The other colors reverse, too—red for green and so on.

Color Filters. For the first time, the iPhone can help you if you’re color blind. The Color Filters option gives you special screen modes that substitute colors you can see for colors you can’t, everywhere on the screen. Tap the various color-blindness types in the list (Red/Green, Blue/Yellow, and so on) to see how each affects the crayons or color swatches at the top of the screen. Use the Intensity slider to govern the degree of the effect.

The Color Tint option washes the entire screen with a certain shade (which you choose using the Hue slider that appears); it’s designed to help people with Irlen syndrome (visual stress), who have trouble reading. The Grayscale option removes all color from the screen. Everything looks like a black-and-white photo.)

The phone’s colors may now look funny to other people, but you should have an easier time distinguishing colors when it counts. (You may even be able to pass some of those Ishihara dot-pattern color-blindness tests online.)

Reduce White Point makes all colors ever depicted on the screen less intense—including the white of the background, which becomes a little yellowish.

Speech

Your phone can read to you aloud: an email message, a web page, a text message—anything. Your choices here go like this:

Speak Selection puts a Speak command into the button bar that appears whenever you highlight text in any app. Tap that button to make the phone read the selected text.

Speak Screen simply reads everything on the screen, top to bottom, when you swipe down from the top of the screen with two fingers. Great for hearing an ebook page or email read to you.

Highlight Content. New in iOS 10—and great for dyslexic or beginner readers. If you turn this on, the phone underlines or uses a highlight color on each word or sentence as it’s spoken, depending on your settings here.

Typing Feedback. The phone can speak each Character as you type it (“T,” “O,” “P,” and so on), with or without Character Hints (“T—Tango,” “O—Oscar,” “P—Papa”). Here you can also specify how much delay elapses before the spoken feedback plays; whether you want finished words and autocorrect suggestions spoken, too; and whether you want to hear QuickType suggestions (QuickType) pronounced when you hold your finger down on them.

This feature, of course, helps blind people know what they’re typing. But it also means that you don’t have to take your eyes off the keyboard, which is great for speed and concentration. And if you’re zoomed in, you may not be able to see the suggested word appear under your typed text—but now you’ll still know what the suggestion is.

Voices gives you a choice of languages and accents for the spoken voice. Try Australian; it’s really cute.

Pronunciations. At last: In iOS 10, you can now correct the phone’s pronunciation of certain words it always gets wrong. Type the word into the Phrase box; tap the

and speak how it should be pronounced; and then, from the list of weird phonetic symbol-written alternatives, tap the one that sounds correct. This technique corrects how your phone pronounces those words or names whenever it speaks, including Siri and the text-to-speech feature described in Dictation.

and speak how it should be pronounced; and then, from the list of weird phonetic symbol-written alternatives, tap the one that sounds correct. This technique corrects how your phone pronounces those words or names whenever it speaks, including Siri and the text-to-speech feature described in Dictation.

How to De-Sparsify iOS 10’s Design

When Apple introduced the sparse, clean design of iOS 7 (which carries over into iOS 10), thousands blogged out in dismay: “It’s too lightweight! The fonts are too spindly! The background is too bright! There aren’t rectangles around buttons—we don’t know what’s a button and what’s not! The Control Center is transparent—we can’t read it! You moved our cheese—we hate this!”

Well, Apple may not agree with you about the super-lightweight design. But at least it has given you options to change it. You can make the type bigger and bolder, the colors heavier, the background dimmer. You can restore outlines around buttons. And so much more.

All of these options await in Settings→General→Accessibility.

Larger Text

This option is the central control panel for iOS’s Dynamic Type feature. It’s a game-changer if you, a person with several decades of life experience, often find type on the screen too small.

Using the slider, you can choose a larger type size for all text the iPhone displays in apps like Mail, iBooks, Messages, and so on. This slider doesn’t affect all the world’s other apps—at least until their software companies update them to make them Dynamic Type–compatible. That day, when it comes, will be glorious. One slider to scale them all.

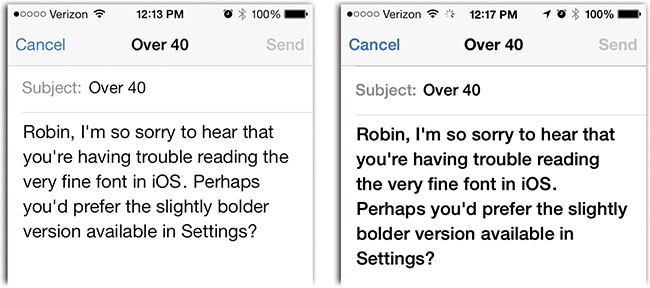

Bold Text

In iOS 10, the system font is fairly light. Its strokes are very thin; in some sizes and lighting conditions, it can even be hard to read.

But if you turn on Bold Text (and then tap Continue in the confirmation box), your iPhone restarts—and when it comes to, the fonts everywhere are slightly heavier: at the Home screen, in email, everywhere. And much easier to read with low light or aging eyesight.

It’s one of the most useful features in iOS—and something almost nobody knows about.

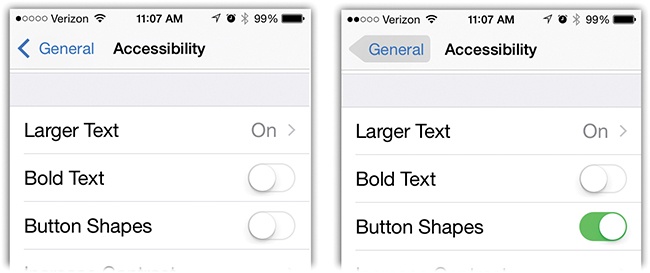

Button Shapes

Among the criticisms of iOS’s design these days: You can’t tell what’s a button anymore! Everything is just words floating on the screen, without border rectangles to tell you what’s tappable!

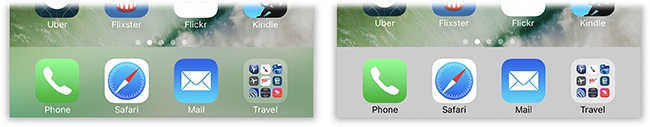

That’s not quite true; any text in blue type is a tappable button. But never mind that; if you want shapes around your buttons, you shall have them—when you turn on this switch (below, right).

Increase Contrast

There are two switches in here. Reduce Transparency adds opacity to screens like the Dock and the Notification Center. Their backgrounds are now solid, rather than slightly see-through, so that text on them is much easier to read. (You can see the before and after below.)

Darken Colors makes type in some spots a little darker and heavier. You notice it in the fonts for buttons, in the Calendar, and in Safari, for example.

Reduce Motion

What kind of killjoy would want to turn off the subtle “parallax motion” of the Home screen background behind your icons, or the zooming-in animation when you open an app?

In any case, you can if you want, thanks to this button.

On/Off Labels

The Settings app teems with little tappable on/off switches, including this one. When something is turned on, the background of the switch is green; when it’s off, the background is white.

But if you’re having trouble remembering that distinction, turn on this option. Now the background of each switch sprouts visible symbols to help you remember that green means On (you see a | marking) and white means Off.

Switch Control

Suppose your physical skills are limited to very simple gestures: puffing on an air pipe, pressing a foot switch, blinking an eye, or turning the head, for example. A hardware accessory called a switch lets you operate certain gadgets this way.

When you turn on Switch Control, the iPhone warns you that things are about to get very different. Tap OK.

Now the phone sequentially highlights one object on the screen after another; you’re supposed to puff, tap, or blink at the right moment to say, “Yes, this one.”

If you don’t have a physical switch apparatus, you can use one nature gave you: your head. The iPhone’s camera can detect when you turn your head left or right and can trigger various functions accordingly.

If you’d like to try it out, open Settings→General→Accessibility→Switch Control. Tap Switches→Add New Switch→Camera→Left Head Movement.

On this screen, you choose what a left head-turn will mean to your phone. The most obvious option is Select Item, which you could use in conjunction with the sequential highlighting of controls on the screen. But you can also make it mean “Press the Home button,” “Activate Siri,” “Adjust the volume,” and so on.

Once you’ve made your selection, repeat that business for Right Head Movement.

When you return to the Switch Control screen, turn on Switch Control. Now your phone is watching you; whenever you turn your head left or right, it activates the control you set up. Pretty wild.

The controls here let you specify how fast the sequential highlighting proceeds, whether or not it pauses on the screen’s first item, how many times the highlighting cycles through each screenful, and so on.

To turn off Switch Control, tap the on/off switch again. Or, if you’re using some other app, triple-press the Home button to open the Accessibility shortcut panel. If you had the foresight to add Switch Control to its options (Accessibility Shortcut), then one tap does the trick.

Switch Control is a broad (and specialized) feature. To read more about it, open the Accessibility chapter of Apple’s iPhone User Guide: help.apple.com/iphone/10/.

AssistiveTouch

If you can’t hold the phone, you might have trouble shaking it (a shortcut for “Undo”); if you can’t move your fingers, just adjusting the volume might be a challenge.

This feature is Apple’s accessibility team at its most creative. When you turn AssistiveTouch on, you get a new, glowing white circle in a corner of the screen (below at top).

You can drag this magic white ball anywhere on the edges of the screen; it remains onscreen all the time.

When you tap it, the white ball expands into the special palette shown above. It’s offering six ways to trigger motions and gestures on the iPhone screen without requiring hand or multiple-finger movement. All you have to be able to do is tap with a single finger—or even a stylus held in your teeth or foot.

You can add more buttons to this main menu, or switch around which buttons appear here. To do that, open Settings→General→Accessibility→Assistive Touch→Customize Top Level Menu.

Meanwhile, here are the starter six icons:

Voice Control. Touch here when you want to speak to Siri. If you do, in fact, have trouble manipulating the phone, Siri is probably your best friend already. This option, as well as the “Hey Siri” voice command, mean that you don’t even have to hold down the Home button to start her up.

Notification Center, Control Center. As far as most people know, the only way to open the Notification Center is to swipe down the screen from the top; the only way to open the Control Center is to swipe up from the bottom. These buttons, however, give you another way—one that doesn’t require any hand movement. (Tap the same button again to close whichever center you opened.)

Home. You can tap here instead of pressing the physical Home button. (That’s handy when your Home button gets sticky, too.)

Device. Tap this button to open a palette of six functions that would otherwise require you to grasp the phone or push its tiny physical buttons (previous page, right). There’s Rotate Screen (you can tap this instead of turning the phone 90 degrees), Lock Screen (instead of pressing the Sleep switch), Volume Up and Volume Down (instead of pressing the volume keys), and Mute/Unmute (instead of flipping the small Mute switch on the side).

If you tap More, you get some bonus buttons. They include Shake (does the same as shaking the phone to undo typing), Screenshot (as though you’d pressed the Sleep and Home buttons together), Multitasking (brings up the app switcher, as though you’d double-pressed the Home button), and Gestures.

That Gestures button opens up a peculiar palette that depicts a hand holding up two, three, four, or five fingers. When you tap, for example, the three-finger icon, you get three blue circles on the screen. They move together. Drag one of them (with a stylus, for example), and the phone thinks you’re dragging three fingers on its surface. Using this technique, you can operate apps that require multiple fingers dragging on the screen.

Custom. Impressively enough, you can actually define your own gestures. On the AssistiveTouch screen, tap one of the + buttons, and tap then Create New Gesture to draw your own gesture right on the screen, using one, two, three, four, or five fingers.

For example, suppose you’re frustrated in Maps because you can’t do the two-finger double-tap that means “zoom out.” On the Create New Gesture screen, get somebody to do the two-finger double-tap for you. Tap Save and give the gesture a name—“2 double tap,” say.

From now on, “2 double tap” shows up on the Custom screen, ready to trigger with a single tap by a single finger or stylus.

Tip

Apple starts you off with some useful predefined gestures in Custom, each of which might be difficult for some people to trigger in the usual ways. First, there’s Pinch, the two-finger pinch or spread gesture you use to zoom in and out of photos, maps, web pages, PDF documents, and so on. Drag either one of the two handles to stretch them apart. Drag the connecting line to move the point of stretchiness.

Then there’s 3D Touch (on the iPhone 6s and later models, that’s a hard-press). And there’s Double Tap (two quick presses in the same spot).

Touch Accommodations

These options are intended to accommodate people who find it difficult to trigger precise taps on the touchscreen. For example:

Touch Accommodations is the master switch for all three of the following options.

Hold Duration requires that you keep your finger on the screen for an amount of time that you specify (for example, 1 second) before the iPhone registers a tap. That feature neatly eliminates accidental taps when your finger happens to bump the screen.

When Hold Duration is turned on, a countdown cursor appears at your fingertip, showing with a circular graph how much longer you have to wait before your touch “counts.”

Ignore Repeat ignores multiple taps that the screen detects within a certain window—say, 1 second. If you have, for example, a tremor, this is a great way to screen out accidental repeated touches or repeated letter-presses on the onscreen keyboard.

Tap Assistance lets you indicate whether the location of a tap should be the first spot you touch or the last spot. The Use Final Touch Location option means you can put your finger down in one spot and then fine-tune its position on the glass anytime within the countdown period indicated by the timer cursor. Feel free to adjust the timer window using the controls here.

3D Touch

The 3D Touch option (Notifications While You’re Working) may be the hot feature of the iPhone 6s and 7 families. But it may also drive you crazy.

Here you can turn the feature off, or just adjust the threshold of pressure (Light, Medium, Firm) required to trigger a “3D touch.” (Apple even gives you a sample photo thumbnail to practice on, right on this screen, so you can gauge which degree of pressure you like best.)

Keyboard

The first option here controls whether or not the onscreen keyboard’s keys turn into CAPITALS when the Shift key is pressed; see Tip.

The others control what happens when you’ve hooked up a physical keyboard to your iPhone—a Bluetooth keyboard, for example:

Key Repeat. Ordinarily, holding down a key makes it repeat, so that you can type things like “auuuuuuuuuuugggggh!” or “zzzzz.” These two sliders govern the repeating behavior: how long you must hold down a key before it starts repeating (to prevent triggering repetitions accidentally), and how fast each key spits out characters once the spitting has begun.

Sticky Keys lets you press multiple-key shortcuts (involving keys like Shift, Option, Control, and

) one at a time instead of all together. (The Sound option ensures that you’ll get an audio beep to confirm that the keyboard has understood.)

) one at a time instead of all together. (The Sound option ensures that you’ll get an audio beep to confirm that the keyboard has understood.)Toggle With Shift Key gives you the flexibility of turning Sticky Keys on and off at will. Whenever you want to turn on Sticky Keys, press the Shift key five times in succession. You’ll hear a special clacking sound effect alerting you that you just turned on Sticky Keys. (Repeat the five presses to turn Sticky Keys off again.)

Shake to Undo

In most of Apple’s apps, you can undo your most recent typing or editing by giving the iPhone a quick shake. (You’re always asked to confirm.) This is the On/Off switch for that feature—handy if you find yourself triggering Undo accidentally.

Vibration

Here’s a master Off switch for all vibrations the phone makes. Alarms, notifications, confirmations—all of it.

As Apple’s lawyers cheerfully point out on this screen, turning off vibrations also means you won’t get buzzy notifications of “earthquake, tsunami, and other emergency alerts.” Goodness!

Call Audio Routing

When a call comes in, where do you want it to go? To your headset? Directly to the speakerphone? Or the usual (headset unless there’s no headset)? Here’s where you make a choice that sticks, so you don’t have to make it each time a call rings.

Home Button

If you have motor-control problems of any kind, you might welcome this enhancement. It’s an option to widen the time window for registering a double-press or triple-press of the Home button. If you choose Slow or Slowest, the phone accepts double- and triple-presses spaced far and even farther apart, rather than interpreting them as individual presses a few seconds apart.

This screen also lets you turn off the new Rest Finger to Open feature, which saves you a click when you’re unlocking the phone (Home Button).

Reachability

Reachability is the feature described in Two Touches: Reachability, the one that brings the top half of the screen downward when you double-touch (not fully press) the Home button. It’s designed to let you reach things on the top of the screen while holding one of the larger iPhones with only one hand. If you find yourself triggering this feature accidentally, you’ll be happy to know that this Off switch awaits.

Hearing Assistance

The next options in Settings→General→Accessibility are all dedicated to helping people with hearing loss.

Hearing Aids

A cellphone is bristling with wireless transmitters, which can cause interference and static if you wear a hearing aid. But the iPhone offers a few solutions.

First, try holding the phone up to your ear normally when you’re on a call. If the results aren’t good, see if you can switch your hearing aid from M mode (acoustic coupling) to T mode (telecoil). If so, turn on Hearing Aid mode (iPhone 5 and later), which makes it work better with T-mode hearing aids.

This settings panel also lets you “pair” your phone with a Bluetooth hearing aid. These wireless hearing aids offer excellent sound but eat hungrily through battery charges.

Hearing aids bearing the “Made for iPhone” logo work especially well—they sound great and don’t drain the battery.

TTY

A TTY is a teletype or text telephone. It’s a machine that lets deaf people make phone calls by typing instead of speaking.

Previous versions of iOS worked with TTY equipment—but in iOS 10, there’s a built-in software TTY that requires no hardware to haul around. It resembles a chat app, and it works like this: When you place a phone call (using the standard Phone app), the iPhone gives you a choice of what kind of call you want to place:

Voice call. Voice-to-voice, as usual.

TTY call. You’re calling another person who also has a TTY machine (or iOS 10). You’ll type back and forth.

TTY relay call. This option means you can call a person who doesn’t have a TTY setup. A human operator will speak (to the other guy) everything you type, and will type (to you) everything the other guy speaks. This, of course, requires a relay service, whose phone number you enter here on this Settings panel.

For more on using TTY on the iPhone, visit https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT207033.

LED Flash for Alerts

If you’re deaf, you know when the phone is ringing—because it vibrates, of course. But what if it’s sitting on the desk, or it’s over there charging? This option lets you know when you’re getting a call, text, or notification by blinking the flash on the back of the phone—the very bright LED light.

Mono Audio

If you’re deaf in one ear, then listening to any music that’s a stereo mix can be frustrating; you might be missing half the orchestration or the vocals. When you turn on the Mono Audio option in Settings→General→Accessibility, the iPhone mixes everything down so that the left and right channels contain the same monaural playback. Now you can hear the entire mix in one ear.

Phone Noise Cancellation

iPhone models 5 and later have three microphones scattered around the body. In combination, they offer extremely good background-noise reduction when you’re on a phone call. The microphones on the top and back, for example, listen to the wind, music, crowd noise, or other ambient sound and subtract that ambient noise from the sound going into the main phone mike.

You can turn that feature off here—if, for example, you experience a “pressure” in your ear when it’s operating.

Balance Slider

The L/R slider lets you adjust the phone’s stereo mix, in case one of your ears has better hearing than the other.

Media (Subtitle Options)

These options govern Internet videos that you play in the iPhone’s Videos app (primarily those from Apple’s own iTunes Store.)

Subtitles & Captioning. The iPhone’s Videos app lets you tap the

button to see a list of available subtitles and captions. Occasionally, a movie also comes with specially written Subtitles for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (SDH). Tap Subtitles & Captioning→Closed Captions + SDH if you want that

button to see a list of available subtitles and captions. Occasionally, a movie also comes with specially written Subtitles for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (SDH). Tap Subtitles & Captioning→Closed Captions + SDH if you want that  menu to list them whenever they’re available.

menu to list them whenever they’re available.The Style option gives you control over the font, size, and background of those captions, complete with a preview. (Tap the

button to view the preview, and the sample caption, at full-screen size.) The Custom option even lets you dream up your own font, size, and color for the type; a new color and opacity of the caption background; and so on.

button to view the preview, and the sample caption, at full-screen size.) The Custom option even lets you dream up your own font, size, and color for the type; a new color and opacity of the caption background; and so on.Audio Descriptions. This new option is for Internet movies that come, or may someday come, with a narration track that describes the action for the blind.

Guided Access (Kiosk Mode)

It’s amazing how quickly even tiny tots can master the iPhone—and how easily they can muck things up with accidental taps.

Guided Access solves that problem rather tidily. It’s kiosk mode. That is, you can lock the phone into one app; the victim cannot switch out of it. You can even specify which features of that app are permitted. Never again will you find your Home screen icons accidentally rearranged or text messages accidentally deleted.

Guided Access is also great for helping out people with motor-control difficulties—or teenagers with self-control difficulties.

To turn on Guided Access, open Settings→General→Accessibility→Guided Access; turn the switch On.

Now a Passcode Settings button appears. Here’s where you protect Guided Access so the little scamp can’t shut it off—at least not without a six-digit passcode (Set Guided Access Passcode) or your fingerprint.

You can also set a time limit for your kid’s Guided Access. Tap Time Limit to set up an alarm or a spoken warning when time is running out.

Finally, the moment of truth arrives: Your kid is screaming for your phone.

Open whatever app you’ll want to lock in place. Press the Home button three times fast. The Guided Access screen appears. At this point, you can proceed in any of three ways:

Declare some features off-limits. With your finger, draw a circle around each button, slider, and control you want to deactivate. The phone converts your circle to a tidy rectangle; you can drag its corners to adjust its size, drag inside the rectangle to move it, or tap the

to remove it if you change your mind or want to start again.

to remove it if you change your mind or want to start again.Once you enter Guided Access mode, the controls you’ve enclosed appear darkened (above, right). They no longer respond—and your phone borrower can’t get into trouble.

Change settings. If you tap Options, you get additional controls. You can decide whether or not your little urchin is allowed to press the Sleep/Wake Button or the Volume Buttons when in Guided Access mode. If you want to hand the phone to your 3-year-old in the back seat to watch baby videos, you’ll probably want to disable the touchscreen altogether (turn off Touch) and prevent the picture from rotating when the phone does (turn off Motion).

Here, too, is the Time Limit switch. Turn it on to view hours/minutes dials. At the end of this time, it’s no more fun for Junior.

Begin kiosk mode. Tap Start.

Later, when you get the phone back and you want to use it normally, triple-press the Home button again; enter your passcode or offer your fingerprint. At this point, you can tap Options to change them, Resume to go back into kiosk mode, or End to return to the iPhone as you know it.

Tip

If you use any of the other accessibility features described in this chapter, you may be dismayed to discover that you can no longer use the triple-clicking of the Home button to open the on/off buttons for those features. The triple-click has been taken over by Guided Access!

Fortunately, Apple has anticipated this problem. If you turn on Accessibility Shortcut on the Guided Access screen of Settings (see the next page), then triple-clicking produces the usual list of accessibility features—and Guided Access is on that list, too, ready to tap.

The Instant Screen-Dimming Trick

The Accessibility settings offer one of the greatest shortcuts of all time: the ability to dim your screen, instantly, with a triple-click on the Home button. You don’t have to open the Control Center, visit Settings, or fuss with a slider; it’s instantaneous. This trick is Apple’s gift to people who go to movies, plays, nighttime drives, or anywhere else where full screen brightness isn’t appropriate, pleasant, or comfortable—and digging around in the Control Center or Settings takes too much time.

It’s a bunch of steps to set up, but you have to take them only once. After that, the magic is yours whenever you want it.

Ready? Here’s the setup.

Open Settings→General→Accessibility. Turn on Zoom.

At this point, the magnifying lens may appear. But you’re interested in dimming, not zooming, so:

Tap the white handle at the bottom of the magnifying lens; in the shortcut menu, tap Zoom Out (next page, left).

Now the magnifying lens is gone.

Scroll down; tap Zoom Filter; tap Low Light (above, right). Tap Zoom (in the upper left) to return to the previous panel.

You’ve just set up the phone to dim the screen whenever Zooming is turned on. Now all you have to do is teach the phone to enable Zooming whenever you triple-click the Home button.

In the top-left corner, tap Accessibility.

You return to the main Accessibility screen. Scroll to the very bottom.

Tap Accessibility Shortcut; make sure Zoom is the only selected item.

At this point, you can press the Home button to get out of Settings.

From now on, whenever you triple-click the Home button, you turn on a gray filter that cuts the brightness of the screen by 30 percent. (Feel free to fine-tune the dimness of your new Insta-Dim setting at that point, using the Control Center; see Control Center.) It doesn’t save you any battery power, since the screen doesn’t think it’s putting out any less light. But it does give you instant darkening when you need it in a hurry—like when a potentially important text comes in while you’re in the movie theater.

Triple-click again to restore the original brightness, and be glad.

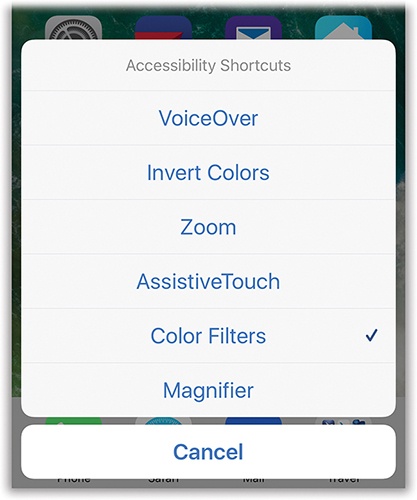

Accessibility Shortcut

Burrowing all the way into the Settings→General→Accessibility screen is quite a slog when all you want to do is flip some feature on or off. Therefore, you get this handy shortcut: a fast triple-press of the Home button.

That action produces a little menu, in whatever app you’re using, with on/off switches for the iPhone’s various accessibility features.

It’s up to you, however, to indicate which ones you want on that menu. That’s why you’re on this screen—to turn on the features you want to appear on the triple-press menu. Your options are Magnifier, VoiceOver, Invert Colors, Color Filters, Reduce White Point, Zoom, Switch Control, and AssistiveTouch.