Chapter 2. The Guided Tour

You can’t believe how much is hidden inside this sleek, thin slab. Microphone, speaker, cameras, battery. Processor, memory, power processing. Sensors for brightness, tilt, and proximity. Twenty wireless radio antennas. A gyroscope, accelerometer, and barometer.

For the rest of this book, and for the rest of your life with the iPhone, you’ll be expected to know what’s meant by, for example, “the Home button” and “the Sleep switch.” A guided tour, therefore, is in order.

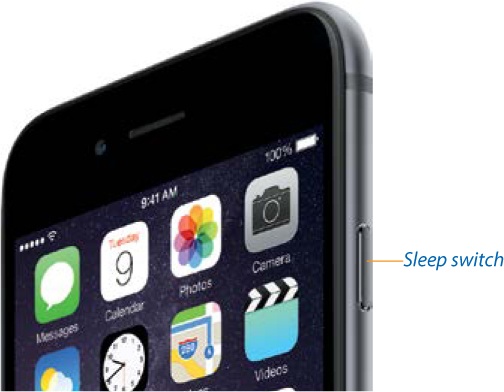

Sleep Switch (On/Off)

You could argue that knowing how to turn on your phone might be a useful skill.

For that, you need the Sleep switch. It’s a metal button shaped like a dash. On the iPhone 6 and later models, it’s on the right edge; on the 5 family and SE, it’s on the top edge.

It has several functions:

Sleep/wake. Tapping it once puts the iPhone into Sleep mode, ready for incoming calls but consuming very little power. Tapping it again turns on the screen so it’s ready for action.

On/Off. The same switch can also turn the iPhone off completely so it consumes no power at all; incoming calls get dumped into voicemail. You might turn the iPhone off whenever you’re not going to use it for a few days.

To turn the iPhone off, hold down the Sleep switch for 3 seconds. The screen changes to say slide to power off.

Confirm your decision by placing a fingertip on the

and sliding to the right. The device shuts off completely.

and sliding to the right. The device shuts off completely.Tip

If you change your mind about turning the iPhone off, then tap the Cancel button or do nothing; after a moment, the iPhone backs out of the slide to power off screen automatically.

To turn the iPhone back on, press the switch again for 1 second. The Apple logo appears as the phone boots up.

Answer call/Dump to voicemail. When a call comes in, you can tap the Sleep button once to silence the ringing or vibrating. After four rings, the call goes to voicemail.

You can also tap it twice to dump the call to voicemail immediately. (Of course, because they didn’t hear four rings, iPhone veterans will know you’ve blown them off. Bruised egos may result. Welcome to the world of iPhone etiquette.)

Force restart. The Sleep switch has one more function. If your iPhone is frozen, and no buttons work, and you can’t even turn the thing off, this button is also involved in force-restarting the whole machine. Steps for this last-ditch procedure are in Note.

Sleep Mode

When you don’t touch the screen for 1 minute (or another interval you choose), or when you press the Sleep switch, the phone goes to sleep. The screen is dark and doesn’t respond to touch.

If you’re on a call, the call continues; if music is playing, it keeps going; if you’re recording audio, the recording proceeds. But when the phone is asleep, you don’t have to worry about accidental button pushes. You wouldn’t want to discover that your iPhone has been calling people or taking photos from the depths of your pocket or purse. Nor would you want it to dial a random number from your back pocket, a phenomenon that’s earned the unfortunate name butt dialing.

The Lock Screen

In iOS 10, the iPhone has a newly expanded state of being that’s somewhere between Sleep and on. It’s the Lock screen. You can actually get a lot done here, without ever unlocking the phone and advancing to its Home screens.

You can wake the phone by pressing the Home button or the Sleep button. Or—if you have an iPhone SE, 6s family, or 7 family—you can do something new and game-changing: Just lift the phone to a vertical position.

The screen lights up, and you’re looking at the Lock screen. Here—even before you’ve entered your password or used your fingerprint—you can check the time, read your missed messages, consult your calendar, take a photo, and more.

Note

You can turn off the new “wake when I lift you” feature. It’s in Settings→Display & Brightness; turn off Raise to Wake. Now you have to press Sleep or Home to wake the phone, as before.

In iOS 10, this new netherworld of activity between Sleep and On—the Lock screen—is a complex, rich, busy universe; see Chapter 3.

Now then: If you want to proceed to the Home screens—to finish turning on the phone—then click the Home button at this point. That’s a new habit to learn; you no longer do that by swiping across the screen, as you have on all iPhones since 2007.

Tip

iOS 10 offers a buried but powerful new option: Rest Finger to Open. (It’s in Settings→General→Accessibility→Home Button.) When you turn this on, the second click—the one to get past the Lock screen—is no longer necessary.

If your phone is asleep, then just lifting it up (with your finger touching the Home button) wakes it and unlocks it; you never even see the Lock screen. Or, if the phone is asleep, you can click the Home button and just leave your finger on it. In each case, you save at least one Home-button click.

So what if you do want to visit the Lock screen? Just raise the phone, or click the Sleep button, without touching the Home button.

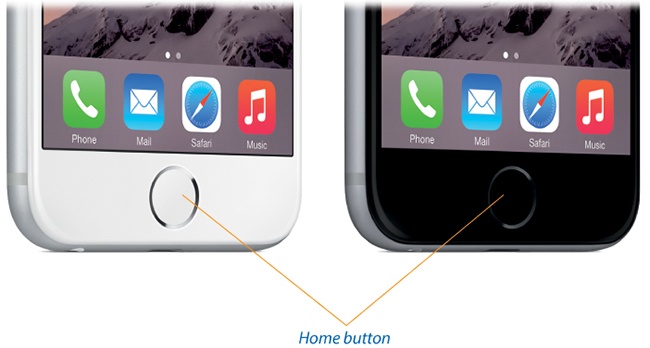

Home Button

Here it is: the one and only button on the front of the phone. Push it to summon the Home screen, your gateway to everything the iPhone can do.

The Home button is a wonderful thing. It means you can never get lost. No matter how deeply you burrow into the iPhone software, no matter how far off-track you find yourself, one push of the Home button takes you back to the beginning. (On the iPhone 7, it doesn’t actually move, but it feels like it does; see What’s New in iOS 10.)

On the iPhone 5s and later models, of course, the Home button is also a fingerprint scanner—the first one on a cellphone that actually works.

But, as time goes on, Apple keeps saddling the Home button with more functions. It’s become Apple’s only way to provide shortcuts for common features; that’s what you get when you design a phone that has only one button. In iPhone Land, you can press the Home button one, two, or three times for different functions—or even hold it down or touch it lightly for others. Here’s the rundown.

Quick Press: Wake Up

Pressing the Home button once wakes the phone if it’s asleep. That’s sometimes easier than finding the Sleep switch on the top or edge. It opens the Lock screen, where you can check notifications or the time, hop into the camera, check your calendar, and more. See Chapter 3.

Momentary Touch: Unlock (iPhone 5s and Later)

Whenever you’re looking at the Enter Passcode screen, just resting your finger on the Home button is enough to unlock the phone. (Teaching the iPhone to recognize your fingerprint is described in Fingerprint Security (Touch ID).) You proceed to the Home screen. That convenience is brought to you by the Touch ID fingerprint reader that’s built into the Home button.

Long Press: Siri

If you hold down the Home button for about 3 seconds, you wake up Siri, your virtual voice-controlled assistant. Details are in Chapter 6.

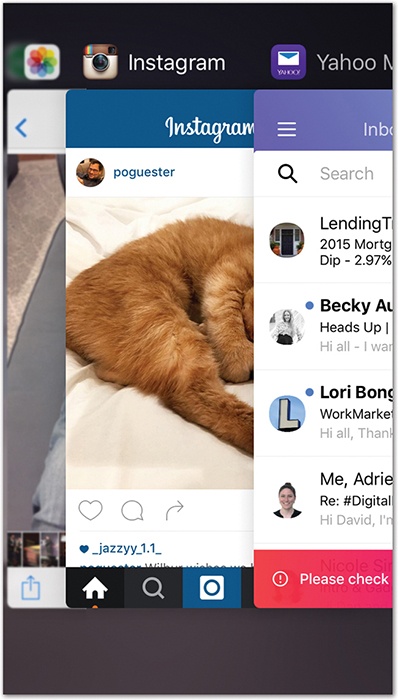

Two Quick Presses: App Switcher

If, once the phone is awake, you press the Home button twice quickly, the current image fades away—to reveal the app-switcher screen, the key to the iPhone’s multitasking feature.

What you see here are currently open screens of the apps you’ve used most recently (older ones are to the left). They appear at nearly full size, overlapping like playing cards. Swipe horizontally to bring more apps into view; the Home screen is always at the far right.

With a single tap on a screen’s “card,” you jump right back into an app you had open, without waiting for it to start up, show its welcome screen, and so on—and without having to scroll through 11 Home screens trying to find its icon.

In short, the app switcher gives you a way to jump directly to another app, without a layover at the Home screen first.

Tip

On this screen, you can also quit a program by flicking it upward. In fact, you can quit several programs at once that way, using two or three fingers. Fun for the whole family!

This app switcher is the only visible element of the iPhone’s multitasking feature. Once you get used to it, that double-press of the Home button will become second nature—and your first choice for jumping among apps.

Two Touches: Reachability

Starting with the iPhone 6, the standard iPhone got bigger than previous models—and the Plus models are even biggerer. Their screens are so big, in fact, that your dinky human thumb may be too small to reach the top portion of the screen (if you’re gripping the phone near the bottom).

For that reason, Apple has built a feature called Reachability into the iPhone 6 and later models. When you tap the Home button twice (don’t click it—just touch it), the entire screen image slides halfway down the glass, so that you can reach the upper parts of it with your thumb!

As soon as you touch anything on the screen—a link, a button, an empty area, anything—the screen snaps back to its usual, full-height position. (The on/off switch for Reachability is in Settings→General→Accessibility.)

Three Presses: Magnifier, VoiceOver, Zoom...

In Settings→General→Accessibility, you can set up a triple-press of the Home button to turn one of several accessibility features on or off. There’s the Magnifier, new in iOS 10 (turns the iPhone into a giant electronic illuminated magnifying glass); VoiceOver (the phone speaks whatever you touch), Invert Colors (white-on-black type, which is sometimes easier to see), Grayscale (a mode that makes the whole iPhone black and white); Zoom (magnifies the screen), Switch Control (accommodates external gadgets like sip-and-puff straws), and AssistiveTouch (help for people who have trouble with physical switches).

All these features are described in Chapter 7.

Silencer Switch, Volume Keys

Praise be to the gods of technology—this phone has a silencer switch! This tiny flipper, on the left edge or at the top, means that no ringer or alert sound will humiliate you in a meeting, at a movie, or in church. To turn off the ringer, push the flipper toward the back of the phone (see the photo on Sleep Switch (On/Off)).

No menus, no holding down keys, just instant silence.

Note

Even when silenced, the iPhone still makes noise in certain circumstances: when an alarm goes off; when you’re playing music; when you’re using Find My iPhone (My Photo Stream, Photo Sharing); when you’re using VoiceOver; or, sometimes, when a game is playing. Also, the phone still vibrates when the silencer is engaged, although you can turn this feature off in Settings→Sounds.

On the left edge are the volume controls. They work in five ways:

On a call, these buttons adjust the speaker or earbud volume.

When you’re listening to music, they adjust the playback volume—even when the phone is locked and dark.

When you’re taking a picture, either one serves as a shutter button or as a camcorder start/stop button.

At all other times, they adjust the volume of sound effects like the ringer, alarms, and Siri.

When a call comes in, they silence the ringing or vibrating.

In each case, if the screen is on, a volume graphic appears to show you where you are on the volume scale.

Screen

The touchscreen is your mouse, keyboard, dialing pad, and notepad. You might expect it to get fingerprinty and streaky.

But the modern iPhone has an oleophobic screen. That may sound like an irrational fear of yodeling, but it’s actually a coating that repels grease. A single light wipe on your clothes restores the screen to its right-out-of-the-box crystal sheen.

You can also use the screen as a mirror when the iPhone is off.

The iPhone’s Retina screen has crazy high resolution (the number of tiny pixels per inch). It’s really, really sharp, as you’ll discover when you try to read text or make out the details of a map or a photo. The iPhone 5 and SE models manage 1136×640 pixels; the iPhone 6/6s/7 packs in 1334×750; the SE has 640×1136; and the Plus models have 1920x1080 (the same number of dots as a high-definition TV).

The front of the iPhone is made of a special formulation made by Corning, to Apple’s specifications—even better than Gorilla Glass, Apple says. It’s unbelievably resistant to scratching. (You can still shatter it if you drop it just the wrong way.)

Note

This is how Corning’s website says this glass is made: “The glass is placed in a hot bath of molten salt at a temperature of approximately 400°C. Smaller sodium ions leave the glass, and larger potassium ions from the salt bath replace them. These larger ions take up more room and are pressed together when the glass cools, producing a layer of compressive stress on the surface of the glass.”

But you probably guessed that.

If you’re nervous about protecting your iPhone, you can always get a case for it (or a “bumper”—a silicone band that wraps the edges). But if you’re worried about scratching the glass, you’re probably worrying too much. Even many Apple employees carry the iPhone in their pockets without cases.

Screen Icons

Here’s a roundup of the icons you may see in the status bar at the top of the iPhone screen, from left to right:

Cell signal (

). As on any cellphone, the number of bars—or dots, in iOS’s case—indicates the strength of your cell signal, and thus the quality of your call audio and the likelihood of losing the connection. If there are no dots, then the dreaded words “No service” appear here.

). As on any cellphone, the number of bars—or dots, in iOS’s case—indicates the strength of your cell signal, and thus the quality of your call audio and the likelihood of losing the connection. If there are no dots, then the dreaded words “No service” appear here.Network name and type. These days, different parts of the country—and even your street—are blanketed by cellular Internet signals of different speeds, types, and ages. Your status bar shows you the kind of network signal it has. From slowest to fastest:

or

or  means your iPhone is connected to your carrier’s slowest, oldest Internet system. You might be able to check email, but you’ll lose your mind waiting for a web page to load.

means your iPhone is connected to your carrier’s slowest, oldest Internet system. You might be able to check email, but you’ll lose your mind waiting for a web page to load.If you see

, you’re in a city where your cell company has installed a 3G network—still slow compared to

, you’re in a city where your cell company has installed a 3G network—still slow compared to  , which offers speed in between 3G and LTE.

, which offers speed in between 3G and LTE.And if you see

up there—well, get psyched. You have an iPhone 5 or later model, and you’re in a city with a 4G LTE cellular network. And that means very fast Internet.

up there—well, get psyched. You have an iPhone 5 or later model, and you’re in a city with a 4G LTE cellular network. And that means very fast Internet.Note

You may also see a notation like “T-Mobile Wi-Fi” or “VZW Wi-Fi” up there. The iPhone 6/6s/7 models, it turns out, can make free phone calls over a Wi-Fi network—if your cellphone carrier has permitted it, and if you’ve turned the feature on (A Word About VoLTE). It’s a great way to make calls indoors where the cell signal is terrible.

Airplane mode (

). If you see the airplane instead of signal and Wi-Fi bars, then the iPhone is in airplane mode (Airplane Mode and Wi-Fi Off Mode).

). If you see the airplane instead of signal and Wi-Fi bars, then the iPhone is in airplane mode (Airplane Mode and Wi-Fi Off Mode).Do Not Disturb (

). When the phone is in Do Not Disturb mode, nothing can make it ring, buzz, or light up except calls from the most important people. Details are in Remind Me Later.

). When the phone is in Do Not Disturb mode, nothing can make it ring, buzz, or light up except calls from the most important people. Details are in Remind Me Later.Wi-Fi signal (

). When you’re connected to a wireless Internet hotspot, this indicator appears. The more “sound waves,” the stronger the signal.

). When you’re connected to a wireless Internet hotspot, this indicator appears. The more “sound waves,” the stronger the signal.9:41 AM. When the iPhone is unlocked, a digital clock appears on the status bar.

Alarm (

). You’ve got an alarm set. This reminder, too, can be valuable, especially when you intend to sleep late and don’t want an alarm to go off.

). You’ve got an alarm set. This reminder, too, can be valuable, especially when you intend to sleep late and don’t want an alarm to go off.Bluetooth (

). The iPhone is connected wirelessly to a Bluetooth earpiece, speaker, or car system. (If this symbol is gray, then it means Bluetooth is turned on but not connected to any other gear—and not sucking down battery power.)

). The iPhone is connected wirelessly to a Bluetooth earpiece, speaker, or car system. (If this symbol is gray, then it means Bluetooth is turned on but not connected to any other gear—and not sucking down battery power.)TTY (

). You’ve turned on Teletype mode, meaning that the iPhone can communicate with a Teletype machine. (That’s a special machine that lets deaf people make phone calls by typing and reading text. It hooks up to the iPhone with a special cable that Apple sells from its website.)

). You’ve turned on Teletype mode, meaning that the iPhone can communicate with a Teletype machine. (That’s a special machine that lets deaf people make phone calls by typing and reading text. It hooks up to the iPhone with a special cable that Apple sells from its website.)Call forwarding (

). You’ve told your iPhone to auto-forward any incoming calls to a different number. This icon is awfully handy—it explains at a glance why your iPhone never seems to get calls anymore.

). You’ve told your iPhone to auto-forward any incoming calls to a different number. This icon is awfully handy—it explains at a glance why your iPhone never seems to get calls anymore.VPN (

). You corporate stud, you! You’ve managed to connect to your corporate network over a secure Internet connection, probably with the assistance of a systems administrator—or by consulting Virtual Private Networking (VPN).

). You corporate stud, you! You’ve managed to connect to your corporate network over a secure Internet connection, probably with the assistance of a systems administrator—or by consulting Virtual Private Networking (VPN).Syncing (

). The iPhone is currently syncing with some Internet service—iCloud, for example (Chapter 17).

). The iPhone is currently syncing with some Internet service—iCloud, for example (Chapter 17).Battery meter (

). When the iPhone is charging, the lightning bolt appears. Otherwise, the battery logo “empties out” from right to left to indicate how much charge remains. (You can even add a “% full” indicator to this gauge; see Meet Haptics.)

). When the iPhone is charging, the lightning bolt appears. Otherwise, the battery logo “empties out” from right to left to indicate how much charge remains. (You can even add a “% full” indicator to this gauge; see Meet Haptics.)Navigation active (

). You’re running a GPS navigation app, or some other app that’s tracking your location, in the background (yay, multitasking!). Why is a special icon necessary? Because those GPS apps slurp down battery power like a thirsty golden retriever. Apple wants to make sure you don’t forget you’re running it.

). You’re running a GPS navigation app, or some other app that’s tracking your location, in the background (yay, multitasking!). Why is a special icon necessary? Because those GPS apps slurp down battery power like a thirsty golden retriever. Apple wants to make sure you don’t forget you’re running it.Rotation lock (

). This icon reminds you that you’ve deliberately turned off the screen-rotation feature, where the screen image turns 90 degrees when you rotate the phone. Why would you want to? And how do you turn the rotation lock on or off? See here for more information.

). This icon reminds you that you’ve deliberately turned off the screen-rotation feature, where the screen image turns 90 degrees when you rotate the phone. Why would you want to? And how do you turn the rotation lock on or off? See here for more information.

Cameras and Flash

At the top of the phone, above the screen, there’s a horizontal slot. That’s the earpiece. Just above it or beside it, the tiny pinhole is the front-facing camera. It’s more visible on the white-faced iPhones than on the black ones.

Its primary purpose is to let you take selfies and conduct video chats using the FaceTime feature, but it’s also handy for checking for spinach in your teeth.

It’s not nearly as good a camera as the one on the back, though. The front camera isn’t as good in low light and takes much lower-resolution shots.

A tiny LED lamp appears next to this back lens—actually, it’s two lamps on the 5s, 6, and 6s iPhones, and four on the 7 family. That’s the flash for the camera, the video light when you’re shooting movies, and a darned good flashlight for reading restaurant menus and theater programs in low light. (Swipe up from the bottom of the screen and tap the  icon to turn the light on and off.)

icon to turn the light on and off.)

The tiny pinhole between the flash and the lens is a microphone. It’s used for recording clearer sound with video, for better noise cancellation on phone calls, and for better directional sound pickup.

The iPhone 7 Plus actually has two lenses on the back—one wide-angle, one zoomed in. Details on this feature and everything else on the iPhone’s cameras are in Chapter 10.

Sensors

Behind the glass, above or beside the earpiece, are two sensors. (On the black iPhones, you can’t see them except with a flashlight.) First, there’s an ambient-light sensor that brightens the display when you’re in sunlight and dims it in darker places.

Second, there’s a proximity sensor. When something (like your head) is close to the sensor, it shuts off the screen and touch sensitivity. It works only in the Phone app. You save power and avoid dialing with your cheekbone when you’re on a call.

SIM Card Slot

On the right edge of the iPhone, there’s a pinhole next to what looks like a very thin slot cover. If you push an unfolded paper clip straight into the hole, the SIM card tray pops out.

So what’s a SIM card?

It turns out that there are two major cellphone network types: CDMA, used by Verizon and Sprint, and GSM, used by AT&T, T-Mobile, and most other countries around the world.

Every GSM phone stores your phone account info—things like your phone number and calling-plan details—on a tiny memory card known as a SIM (subscriber identity module) card.

What’s cool is that, by removing the card and putting it into another GSM phone, you can transplant a GSM phone’s brain. The other phone now knows your number and account details, which can be handy when your iPhone goes in for repair or battery replacement. For example, you can turn a Verizon iPhone 7 into a T-Mobile iPhone 7 just by swapping in a T-Mobile SIM card.

The World Phone

AT&T is a GSM network, so AT&T iPhones have always had SIM cards. But, intriguingly enough, every iPhone has a SIM card, too—even the Verizon and Sprint models. That’s odd, because most CDMA cellphones don’t have SIM cards.

These iPhones contain antennas for both GSM and CDMA. It’s the same phone, no matter which cell company you buy it from. Only the SIM card teaches it which one it “belongs” to.

Even then, however, you can still use any company’s phone in any country. (That’s why the latest iPhones are said to be “world phones.”) When you use the Verizon or Sprint iPhone in the United States, it uses only the CDMA network. But if you travel to Europe or another GSM part of the world, you can still use your Verizon or Sprint phone; it just hooks into that country’s GSM network.

If you decide to try that, you have two ways to go. First, you can contact your phone carrier and ask to have international roaming turned on. You’ll keep your same phone number overseas, but you’ll pay through the nose for calls and, especially, Internet use. (One exception: On T-Mobile, international texting and Internet use are free.)

Second, you can rent a temporary SIM card when you get to the destination country. That’s less expensive, but you’ll have a different phone number while you’re there.

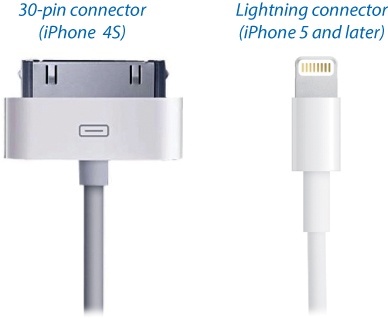

The iPhone 4s used a card type known as a micro-SIM card. And for the iPhone 5 and later, Apple developed even tinier cards called nano-SIMs. (You can see all three at left.)

At this rate, you won’t be able to see the iPhone 8’s SIM card without an electron microscope.

Apple thinks SIM cards are geeky and intimidating and that they should be invisible. That’s why, unlike most GSM phones, your iPhone came with the card preinstalled and ready to go. Most people never have any reason to open this tray.

If you were curious enough to open it up, you can close the tray simply by pushing it back into the phone until it clicks.

Headphone Jack

Until the iPhone 7 came along, iPhones contained a standard jack for plugging in the white earbuds that came with it—or any other earbuds or headphones.

It’s more than an ordinary 3.5-millimeter audio jack, however. It contains a secret fourth pin that conducts sound into the phone from the microphone on the earbuds’ cord. You, too, can be one of those executives who walk down the street barking orders, apparently to nobody.

The iPhone can stay in your pocket as you walk or drive. You hear the other person through your earbuds, and the mike on the cord picks up your voice.

Note

Next to the headphone jack, inside a perforated grille, a tiny second microphone lurks. It’s the key to the iPhone’s noise-cancellation feature. It listens to the sound of the world around you and pumps in the opposite sound waves to cancel out all that ambient noise. It doesn’t do anything for you—the noise cancellation affects only what the other guy on the phone hears.

That’s why there’s also a third microphone at the top back (between the camera and flash); it’s designed to supply noise cancellation for you so that the other guy sounds better when you’re in a noisy place.

iPhone 7: No Headphone Jack

We, the people, may complain about how exhausting it is to keep up with the annual flood of new smartphones. But at least you don’t have to create the annual set of new features. That’s their problem.

Not just because it’s increasingly difficult to think of new features, but also because the phone makers have pretty much run out of room for new components inside.

That, says Apple, is why it removed the headphone jack from the iPhone 7 and 7 Plus. The headphone jack may not seem very big—but on the inside of the phone, the corresponding receptacle occupies an unnerving amount of nonnegotiable space.

So how are you supposed to listen to music without a headphone jack? Apple offers three ways:

Using the adapter. In the iPhone box, Apple includes a two-inch adapter cord that connects any headphones to the phone’s Lightning jack.

Use the earbuds. The phone also comes with new white earbuds that connect to the Lightning (charging) jack.

Use wireless headphones. You can also use any Bluetooth wireless earbuds—from $17 plastic disposable ones to Apple’s own, super-impressive AirPods. Bluetooth Accessories has more on Bluetooth headsets.

In theory, those three approaches should pretty much cover you whenever you want to listen.

In practice, though, you’ll still get zapped by the occasional inconvenience. You’ll be on a flight, for example, listening to your laptop with headphones—and when you want to switch to the phone, you’ll realize that your adapter cord is in the overhead bin. (Based on a true story.)

But this kind of hassle is the new reality. Motorola and LeEco (in China) have already ditched the headphone jack, and other phone makers will follow suit.

Microphone, Speakerphone

On the bottom of the iPhone, Apple has parked two important audio components: the speaker and the microphone.

On the iPhone 7, in fact, there are two speakers, on the top and bottom of the phone. Stereo sound (and better sound) has finally come to the iPhone.

The Lightning Connector

Directly below the Home button, on the bottom edge of the phone, you’ll find the connector that charges and syncs the iPhone with your computer.

For nearly 10 years, the charge/sync connector was identical on every iPhone, iPod, and iPad—the famous 30-pin connector. But starting on the iPhone 5, Apple replaced that inch-wide connector with a new, far-smaller one it calls Lightning.

The Lightning connector is a great design: It clicks nicely into place (you can even dangle the iPhone from it), yet you can yank it right out. You can insert the Lightning into the phone either way—there’s no “right-side up” anymore. It’s much sturdier than the old connector. And it’s tiny, which was Apple’s primary goal—only 0.3 inches wide (the old one was almost 0.9 inches wide).

Unfortunately, you may still occasionally encounter a car adapter or hotel-room alarm clock with the old kind of connector. (For $30, you can buy an adapter.)

In time, as the Lightning connectors come on all new iPhones, iPods, and iPads, a new ecosystem of accessories will arise. We’ll arrive at a new era of standardization—until Apple changes jacks again in another 10 years.

Antenna Band

Radio signals can’t pass through metal. That’s why there are strips of glass on the back of the iPhone 5, 5s, and SE, strips of plastic on the iPhone 6/6s/7 models, and all plastic on the back of the 5c.

And there are a lot of radio signals in this phone. All told, there are 20 different radio transceivers inside the iPhone 6/6s/7. They tune in to the LTE and 3G (high-speed Internet) signals used in various countries around the world, plus the three CDMA signals used in the U.S.; and one each for Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, American GPS, and Russian GPS.

In the Box

Inside the minimalist box, you get the iPhone and these items:

The earbuds. Every iPhone comes with a pair of the iconic white earbuds that announce to the world, “I have an iPhone!” These days, they’re what Apple calls EarPods. They sound great, although their bulbous shape may get uncomfortable in smaller ears. A volume control/clicker is right there on the cord, so you can answer phone calls and pause the music without even taking the phone out of your pocket. (The EarPods that come with the new iPhone 7, of course, plug into the Lightning jack, since there’s no headphone jack on that model.)

A Lightning cable. When you connect your iPhone to your computer using this white USB cable, it simultaneously syncs and charges. See Chapter 16.

The AC adapter. When you’re traveling without a computer, you can plug the dock’s USB cable into the included two-prong outlet adapter, so you can charge the iPhone directly from a wall socket.

Decals and info card. iPhone essentials.

You don’t need a copy of the iTunes software, or even a computer, to use the iPhone—but it makes loading up the phone a lot easier, as described in Chapter 16.

If you don’t have iTunes on your computer, you can download it from www.apple.com/itunes.

Seven Basic Finger Techniques

On the iPhone, you do everything on the touchscreen instead of with physical buttons.

Tap

The iPhone’s onscreen buttons are nice and big, giving your fleshy fingertip a fat target.

You can’t use a fingernail or a pen tip; only skin contact works. (You can also buy an iPhone stylus. But a fingertip is cheaper and harder to misplace.)

Double-Tap

Double-tapping is pretty rare. It’s generally reserved for two functions:

In the Safari web browser, Photos, and Maps apps, double-tapping zooms in on whatever you tap, magnifying it. (At that point, double-tapping means “Restore to original size.”) Double-tapping also zooms into formatted email messages, PDF files, Microsoft Office files, and other things.

When you’re watching a video (or recording one), double-tapping switches the aspect ratio (video screen shape).

Swipe

In some situations, you’re asked to confirm an action by swiping your finger across the screen. That’s how you confirm that you want to shut off the phone, for example. Swiping like this is also a great shortcut for deleting an email or a text message.

Drag

When you’re zoomed into a map, web page, email, or photo, you scroll around by sliding your finger across the glass in any direction—like a flick (described next), but slower and more controlled. It’s a huge improvement over scroll bars, especially when you want to scroll diagonally.

Flick

A flick is a faster, less-controlled drag. You flick vertically to scroll lists on the iPhone. The faster you flick, the faster the list spins downward or upward. But lists have a real-world sort of momentum; they slow down after a second or two, so you can see where you wound up.

At any point during the scrolling of a list, you can flick again (if you didn’t go far enough) or tap to stop the scrolling (if you see the item you want to choose).

Pinch and Spread

In apps like Photos, Mail, Safari, and Maps, you can zoom in on a photo, message, web page, or map by spreading.

That’s when you place two fingers (usually thumb and forefinger) on the glass and spread them. The image magically grows, as though it’s printed on a sheet of rubber.

Note

The English language has failed Apple here. Moving your thumb and forefinger closer together has a perfect verb: pinching. But there’s no good word to describe moving them the opposite direction.

Apple uses the oxymoronic expression pinch out to describe that move (along with the redundant-sounding pinch in). In this book, the opposite of “pinching” is “spreading.”

Once you’ve zoomed in like this, you can zoom out again by putting two fingers on the glass and pinching them together.

Edge Swipes

Swiping your finger inward from outside the screen has a few variations:

From the top edge. Opens the Notification Center, which lists all your missed calls and texts, shows your appointments, and so on.

From the bottom edge. Opens the Control Center, a unified miniature control panel for brightness, volume, Wi-Fi, and so on.

From the left edge. In many apps, this means “Go back to the previous screen.” It works in Mail, Settings, Notes, Messages, Safari, Facebook, and some other apps. At the Home screen, it opens the Today screen (Miscellaneous Weirdness).

It sometimes makes a big difference whether you begin your swipe within the screen or outside it. At the Home screen, for example, starting your downward swipe within the screen area doesn’t open the Notification Center—it opens Spotlight, the iPhone’s search function.

Tip

If you have an iPhone 6s or 7, you can also hard-swipe from the left edge to open the app switcher described in Quick Press: Wake Up. Actually, all you have to do is hard-press the left margin of the screen, but hard-swiping might fit the metaphor better (pulling the app cards onto the screen).

Force Touch (iPhone 6s and 7)

The screen on the iPhone 6s and 7 (and their Plus siblings) doesn’t just detect a finger touch. It also knows how hard your finger is pressing, thanks to a technology Apple calls Force Touch. This feature requires that you learn two more finger techniques.

Quick Actions

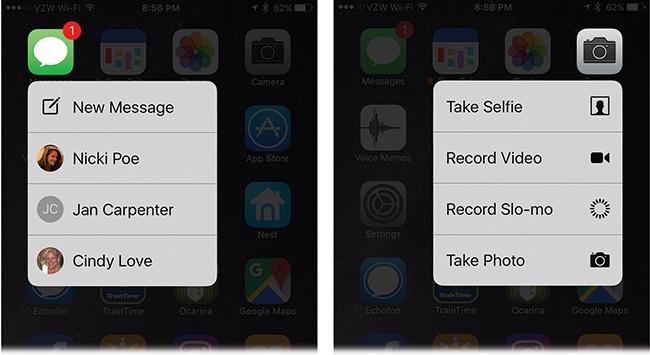

iOS 10 interprets the pressure of your touch in various ways. On the Home screens, you can make a shortcut menu of useful commands pop out of various app icons, like this:

Apple calls these commands quick actions, and each is designed to save you a couple of steps. There are more than ever in iOS 10. Some examples:

The Camera app icon offers shortcut menus like Take Selfie, Record Video, Record Slo-mo, and Take Photo.

The Clock app gives you direct access to its Set Alarm, Start Timer, and Start Stopwatch functions.

Notes gives you New Note, New Photo, and New Sketch commands (a reference to the new finger-drawing features).

Maps offers Directions Home (a great one), Mark My Location, Send My Location, and Search Nearby (for restaurants, bars, shops, and so on).

The Phone app sprouts the names of people you’ve called recently, as well as a Create New Contact command.

Calendar shows your next appointment, plus an Add Event command.

Reminders lists your reminder categories, so you can create a new To Do directly inside one of them (for example, New in Family).

Mail and Messages offer New Message commands. Mail also offers Search, Inbox (with a new-message counter), and VIPs (also with a counter).

Home-screen folders sprout a Rename command at your fingertip.

The Notification Center (the list that appears when you swipe down from the top of the screen) offers a Clear All Notifications command.

The Control Center icons (Note) offer some options. You can hard-press the Flashlight icon to choose Low, Medium, or High brightness. That’s super cool, especially on the iPhone 7, whose much stronger LED flashlight is enough to light up a high-school football game at night. Meanwhile, the Timer button offers presets for 1 minute, 5 minutes, 20 minutes, or 1 hour. And the Camera button offers Take Photo, Record Slo-mo, Record Video, and Take Selfie. That kind of thing.

Similar quick actions also sprout from these Apple apps’ icons: Photos, Video, Wallet, iTunes Store, App Store, iBooks, News, Safari, Music, FaceTime, Podcasts, Voice Memos, Contacts, and Find My Friends.

And, of course, in iOS 10, you can use hard presses to respond to notifications: reply to a text message, accept a Calendar invitation, or see where your Uber is on a map.

Other software companies can add shortcut menus to their apps, too. You’ll find these shortcut menus on the Facebook, Fitbit, and Google Maps app icons, for example.

If you force-press an app that doesn’t have quick actions, you just feel a buzz and nothing else happens.

Note

At the outset, this force-pressing business can really throw you when you’re trying to rearrange icons on your Home screens. As described in Rearranging/Deleting Apps Right on the Phone, that usually involves long-pressing an icon, which for most people is too similar to hard-pressing one. The trick is to long-press very lightly. You’ll get used to it.

Peek and Pop

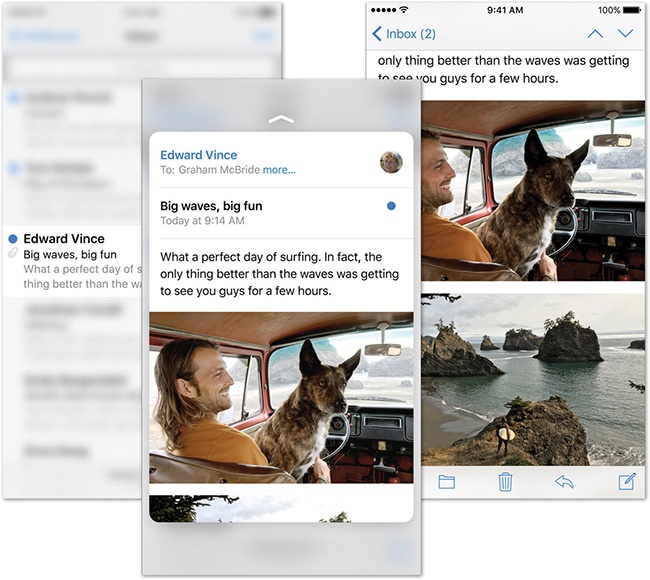

Hard to explain, but very cool: You hard-press something in a list—your email Inbox, for example (below, left). Or a link in a text message, or a photo thumbnail. You get a pop-up bubble showing you what’s inside (middle):

When you release your finger, the bubble disappears, and you’re right back where you started.

Peeking is, in other words, exactly like the Quick Look feature on the Mac. It lets you see what’s inside a link, icon, or list item without losing your place or changing apps.

Email is the killer app here. You can whip through your Inbox, hard-pressing one new message after another—“What’s this one?” “Do I care?”—simply inspecting the first paragraph of each but not actually opening any message.

Then, if you find one that you do want to read fully, you can press harder yet to open the message normally (previous page, right). Apple calls that “popping.”

Here are some places where you can peek in the basic iPhone apps: Mail (preview a message in a list), Messages (see recent exchanges with someone in the list of people), Maps (preview information about a pushpin), Calendar (see details of an event), Photos (preview a photo in a screenful of thumbnails), Safari (preview the page hiding behind a link), Weather (see weather details for a name in the list of cities), Music (see information about a song or album in a list), Video (read details about a video in a list), Notes (see the contents of a note’s name in a list), iBooks (view a book-cover thumbnail larger), News (preview the body of an article in a list), and Find My Friends (see the map identifying the location of someone in your list).

But, for goodness’ sake, at least get to know peek and pop in Mail and Messages. It’s really kind of awesome.

And, again, app makers can add this feature to their own apps.

Charging the iPhone

The iPhone has a built-in, rechargeable battery that fills up most of its interior. How long a charge lasts depends on what you’re doing—music playback saps the battery the least, GPS navigation saps it the most. But one thing is for sure: You’ll have to recharge the iPhone regularly. For most people, it’s every night.

Note

The iPhone’s battery isn’t user-replaceable. It’s rechargeable, but after 400 or 500 charges, it starts to hold less juice. Eventually, you’ll have to pay Apple to install a new battery. (Apple says the added bulk of a protective plastic battery compartment, a removable door and latch, and battery-retaining springs would have meant a much smaller battery—or a much thicker iPhone.)

You recharge the iPhone by connecting the white USB cable that came with it. You can plug the far end into either of two places to supply power:

Your computer’s USB jack. In general, the iPhone charges even if your computer is asleep. (If it’s a laptop that itself is not plugged in, though, the phone charges only if the laptop is awake. Otherwise, you’d come home to a depleted laptop.)

The AC adapter. The little white two-prong cube that came with the iPhone connects to the end of the cradle’s USB cable.

Unless the charge is really low, you can use the iPhone while it charges. The battery icon in the upper-right corner displays a lightning bolt to let you know it’s charging.

Battery Life Tips

The battery life of the iPhone is either terrific or terrible, depending on your point of view and how old your phone is.

If you were an optimist, you’d point out that the iPhone gets longer battery life than most touchscreen phones. If you were a pessimist, you’d observe that you sometimes can’t make it through even a single day without needing a recharge.

So knowing how to scale back your iPhone’s power appetite should come in extremely handy.

These are the biggest wolfers of electricity: the screen and background activity (especially Internet activity). Therefore, when you’re nervous about your battery making it through an important day, here are your options:

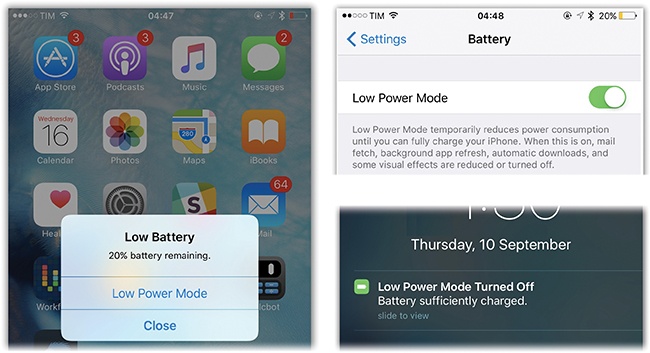

Low Power mode can squeeze another 3 hours of life out of a charge.

In Low Power mode, your iPhone quits doing a lot of stuff in the background, like fetching new mail and updating apps. It also stops playing most of iOS’s cute little animations and stops listening for you to say “Hey Siri” (How to Use “Hey Siri”). The processor slows down, too; it takes longer to switch between apps, for example. And the battery indicator turns yellow, to remind you why things have suddenly slowed down.

When your battery sinks to 20 percent remaining (and then again at 10 percent), you get a warning message. If you choose Low Power Mode in this message box, then boom: You’re in Low Power mode.

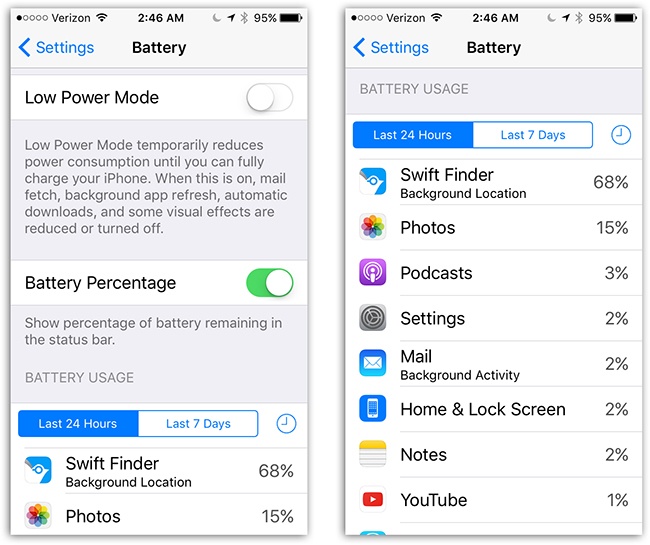

If your phone is plugged in, it exits Low Power mode automatically once it has enough juice (above, lower right). You can also turn Low Power Mode on or off manually in Settings→Battery (above, upper right).

At any time, you can also shut down juice-guzzling features manually. Here they are, roughly in order of power appetite:

Dim the screen. Turning down your screen saves a lot of battery power. The quickest way is to swipe up from the bottom of the screen to open the Control Center (Control Center), and then drag the brightness slider.

On a new iPhone, Auto Brightness is turned on, too. In bright light, the screen brightens automatically; in dim light, it darkens. That’s because when you unlock the phone after waking it, it samples the ambient light and adjusts the brightness.

Note

This works because of the ambient-light sensor near the earpiece. Apple says it experimented with having the light sensor active all the time, but it was weird to have the screen constantly dimming and brightening as you used it.

You can use this information to your advantage. By covering up the sensor as you unlock the phone, you force it into a low-power, dimscreen setting (because the phone believes it’s in a dark room). Or by holding it up to a light as you wake it, you get more brightness. In either case, you’ve saved the navigation it would have taken you to find the manual brightness slider in Settings or in the Control Center. (Or you can turn this auto-brightness feature off altogether in Settings→Display & Brightness.)

Tip

You can set things up so that a triple-click on the Home button instantly dims your screen, for use in the bedroom, movie theaters, or planetariums—without having to fuss with Settings or sliders. See The Instant Screen-Dimming Trick for this awesome trick.

Turn off “push” data. This is a big one. If your email, calendar, and address book are kept constantly synced with your Macs or PCs, then you’ve probably gotten yourself involved with Yahoo Mail, iCloud (Chapter 17), or Microsoft Exchange (Chapter 19). It’s pretty amazing to know that your iPhone is constantly kept current with the mother ship.

Unfortunately, all that continual sniffing of the airwaves, looking for updates, costs you battery power. If you can do without the immediacy, then visit Settings→Mail→Accounts→Fetch New Data. If you turn off the Push feature for each email account and set it to Manually instead, then your iPhone checks for email and new appointments only when you actually open the Mail or Calendar apps. Your battery goes a lot further.

Turn off background updating. Non-Apple apps check for frequent updates, too: Facebook, Twitter, stock-reporting apps, and so on. Not all of them need to be busily toiling in the background. Your best bet for battery life, then, involves visiting Settings→General→Background App Refresh and turning the switch off for each app whose background activity isn’t strictly necessary.

Turn off automatic app updates. As you’ll soon discover, app companies update their wares far more often than PC or Mac apps. Some apps get updated many times a year.

Your phone comes set to download them automatically when they become available. But that constant checking and downloading costs you battery life.

To shut that feature down, open Settings→iTunes & App Store. In the Automatic Downloads section, turn off Updates. (The other switches—Music, Apps, Books—are responsible for auto-downloading things that you or your brood have downloaded on other iOS gadgets. You might want to make sure they’re off, too, if battery life is a concern.)

Turn off GPS checks. In Settings→Privacy→Location Services, there’s a list of all the apps on your phone that are using your phone’s location feature to know where you are. (It’s a combination of GPS, cell-tower triangulation, and Wi-Fi hotspot triangulation.) All that checking uses battery power.

Some apps, like Maps, Find My Friends, and Yelp, don’t do you much good unless they know your location. But plenty of apps don’t really need to know where you are. Facebook and Twitter, for example, want that information only so that they can location-stamp your posts. In any case, the point is to turn off Location Services for each app that doesn’t really need to know where you are.

Turn off Wi-Fi. If you’re not in a wireless hotspot, you may as well stop the thing from using its radio. Swipe up from the bottom of the screen to open the Control Center, and tap the

icon to turn it off.

icon to turn it off.Or at the very least tell the iPhone to stop searching for Wi-Fi networks it can connect to. Silencing the “Want to Join?” Messages has the details.

Turn off Bluetooth. If you’re not using a Bluetooth gadget (headset, fitness band, or whatever), then for heaven’s sake shut down that Bluetooth radio. Open the Control Center and tap the

icon to turn it off.

icon to turn it off.Turn off Cellular Data. This option (in Settings→Cellular) turns off the cellular Internet features of your phone. You can still make calls, and you can still get online in a Wi-Fi hotspot.

This feature is designed for people who have a capped data plan—a limited amount of Internet use per month—which is almost everybody. If you discover that you’ve used up almost all your data allotment for the month, and you don’t want to go over your limit (and thereby trigger an overage charge), you can use this option to shut off all data. Now your phone is just a phone—and it uses less power.

Consider airplane mode. In airplane mode, you shut off all the iPhone’s power-hungry radios. Even a nearly dead iPhone can hobble on for a few hours in airplane mode—something to remember when you’re desperate. To enter airplane mode, swipe up from the bottom of the screen to open the Control Center, and tap the

icon.

icon.Tip

For sure, turn on airplane mode if you’ll be someplace where you know an Internet signal won’t be present—like on a plane, a ship at sea, or Montana. Your iPhone never burns through a battery charge faster than when it’s hunting for a signal it can’t find; your battery will be dead within a couple of hours.

Turn off the screen. With a press of the Sleep button, you can turn off the screen, rendering it black and saving huge amounts of power. Music playback and Maps navigation continue to work just fine.

Of course, if you want to actually interact with the phone while the screen is off, you’ll have to learn the VoiceOver talking-buttons technology; see VoiceOver.

By the way, beware of 3D games and other graphically intensive apps, which can be serious power hogs. And turn off EQ when playing your music (see Switching Among Speakers).

If your battery still seems to be draining too fast, check out this table, which shows you exactly which apps are using the most power:

To see it, open Settings→Battery. You can switch between battery readouts for the past 24 hours, or for the past 7 days. Keep special watch for labels like these:

Low Signal. A phone uses the most power of all when it’s hunting for a cellular signal, because the phone amplifies its radios in hopes of finding one. If your battery seems to be running down faster than usual, the “Low Signal” notation is a great clue—and a suggestion that maybe you should use airplane mode when you’re on the fringes of cellular coverage.

Background activity. As hinted on the previous pages, background Internet connections are especially insidious. These are apps that do online work invisibly, without your awareness—and drain the battery in the process. Now, for the first time, you can clearly see which apps are doing it.

Once you know the culprit app, it’s easy to shut its background work down. Open Settings→General→Background App Refresh and switch off each app whose background activity isn’t strictly necessary.

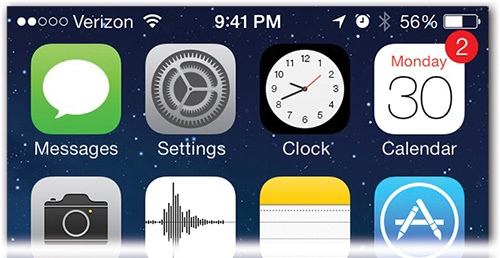

The Home Screen

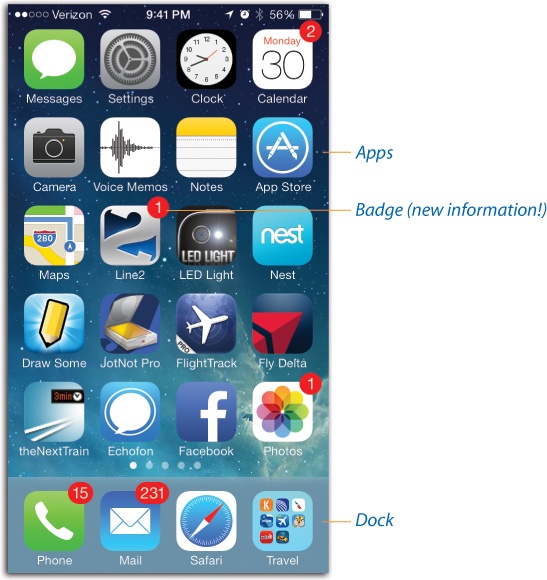

The Home screen is the launching pad for every iPhone activity. It’s what appears when you press the Home button. It’s the immortal grid of colorful icons.

It’s such an essential software landmark, in fact, that a quick tour might be helpful:

Icons. Each icon represents one of your iPhone apps (programs)—Mail, Maps, Camera, and so on—or a folder that you’ve made to contain some apps. Tap one to open that app or folder.

Your iPhone comes with a couple of dozen apps preinstalled by Apple; you can’t remove them. The real fun, of course, comes when you download more apps from the App Store (Chapter 11).

Badges. Every now and then, you’ll see a tiny, red number “badge” (like

) on one of your app icons. It’s telling you that something new awaits: new email, new text messages, new chat entries, new updates for the apps on your iPhone. It’s saying, “Hey, you! Tap me!”

) on one of your app icons. It’s telling you that something new awaits: new email, new text messages, new chat entries, new updates for the apps on your iPhone. It’s saying, “Hey, you! Tap me!”Home page dots. The standard Home screen can’t hold more than 20 or 24 icons. As you install more and more programs on your iPhone, you’ll need more and more room for their icons. Fortunately, the iPhone makes room for them by creating additional Home screens automatically. You can spread your new programs’ icons across 11 such launch screens.

The little white dots are your map. Each represents one Home screen. If the third one is “lit up,” then you’re on the third Home screen.

To move among the screens, swipe horizontally—or tap to the right or left of the little dots to change screens.

And if you ever scroll too far away from the first Home screen, here’s a handy shortcut: Press the Home button (yes, even though you’re technically already home). That takes you back to the first Home screen.

The Dock. At the bottom of the Home screen, four exalted icons sit in a row on a light-colored panel. This is the Dock—a place to park the most important icons on your iPhone. These, presumably, are the ones you use most often. Apple starts you off with the Phone, Mail, Safari, and Music icons there.

What’s so special about this row? As you flip among Home screens, the Dock never changes. You can never lose one of your four most cherished icons by straying from the first page; they’re always handy.

The background. You can replace the background image (behind your app icons) with a photo. A complicated, busy picture won’t do you any favors—it will just make the icon names harder to read—so Apple provides a selection of handsome, relatively subdued wallpaper photos. But you can also choose one of your own photos.

For instructions on changing the wallpaper, see Wallpaper.

It’s easy (and fun!) to rearrange the icons on your Home screens. Put the most frequently used icons on the first page, put similar apps into folders, and reorganize your Dock. Full details are in Rearranging/Deleting Apps Right on the Phone.

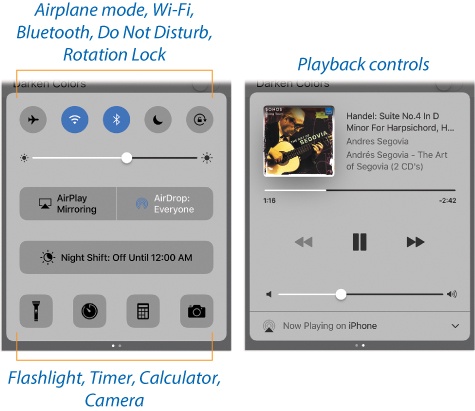

Control Center

For such a tiny device, there are an awful lot of settings you can change—hundreds of them. Trouble is, some of them (volume, brightness) need changing a lot more often than others (language preference, voicemail greeting).

That’s why Apple invented the Control Center: a panel that offers quick access to the controls you need the most.

To open the Control Center, no matter what app you’re using, swipe upward from beneath the screen.

Tip

You can even open the Control Center from the Lock screen (unless you’ve turned off that feature in Settings→Control Center→Access on Lock Screen).

The Control Center is a gray panel filled with one-touch icons for the settings most people change most often on their iPhones.

In iOS 10, there are now two pages of the Control Center, as shown on the facing page. The only hint is the two tiny dots beneath each screen. Over time, you’ll learn to swipe leftward to see the newly separate music playback controls, or to the right to see everything else.

Note

If you’ve set up any HomeKit accessories—remote-controllable lights, locks, thermostats, outlets, and security systems that work with Apple’s Home automation app—then the Control Center sprouts a third page.

Now, many of these settings are even faster to change using Siri, the voice-command feature described in Chapter 6. When it’s not socially awkward to speak to your phone (like at the symphony or during a golf game), you can use spoken commands—listed below under each button description—to adjust settings without even touching the screen.

Here’s what’s in the Control Center:

Airplane mode (

). Tap to turn the icon red. Now you’re in airplane mode; the phone’s wireless features are all turned off. You’re saving the battery and obeying flight attendant instructions. Tap again to turn off airplane mode.

). Tap to turn the icon red. Now you’re in airplane mode; the phone’s wireless features are all turned off. You’re saving the battery and obeying flight attendant instructions. Tap again to turn off airplane mode.Sample Siri command: “Turn airplane mode on.” (Siri warns you that if you turn airplane mode on, Siri herself will stop working. Say “OK.”)

Wi-Fi (

). Tap to turn your phone’s Wi-Fi off (gray) or on (blue).

). Tap to turn your phone’s Wi-Fi off (gray) or on (blue).Sample Siri commands: “Turn off Wi-Fi.” “Turn Wi-Fi back on.”

Bluetooth (

). Tap to turn your Bluetooth transmitter off (gray) or on (blue). That feature alone is a godsend to anyone who uses the iPhone with a car’s Bluetooth audio system. Bluetooth isn’t the battery drain it once was, but it’s still nice to be able to flick it on so easily when you get into the car.

). Tap to turn your Bluetooth transmitter off (gray) or on (blue). That feature alone is a godsend to anyone who uses the iPhone with a car’s Bluetooth audio system. Bluetooth isn’t the battery drain it once was, but it’s still nice to be able to flick it on so easily when you get into the car.Sample Siri commands: “Turn Bluetooth on.” “Turn off Bluetooth.”

Do Not Disturb (

). Do Not Disturb mode, described in Remind Me Later, means that the phone won’t ring or buzz when people call—except a few handpicked people whose communiqués ring through. Perfect for sleeping hours; in fact, you can set up an automated schedule for Do Not Disturb (say, midnight to 7 a.m.).

). Do Not Disturb mode, described in Remind Me Later, means that the phone won’t ring or buzz when people call—except a few handpicked people whose communiqués ring through. Perfect for sleeping hours; in fact, you can set up an automated schedule for Do Not Disturb (say, midnight to 7 a.m.).But what if you wake up early or want to stay up late? Now you can tap to turn Do Not Disturb on (blue) or off (gray).

Sample Siri commands: “Turn on Do Not Disturb.” “Turn Do Not Disturb off.”

Rotation lock (

). When rotation lock is turned on (red), the screen no longer rotates when you turn the phone 90 degrees. The idea is that sometimes, like when you’re reading an ebook on your side in bed, you don’t want the screen picture to turn; you want it to stay upright relative to your eyes. (A little

). When rotation lock is turned on (red), the screen no longer rotates when you turn the phone 90 degrees. The idea is that sometimes, like when you’re reading an ebook on your side in bed, you don’t want the screen picture to turn; you want it to stay upright relative to your eyes. (A little  icon appears at the top of the screen to remind you why the usual rotating isn’t happening.)

icon appears at the top of the screen to remind you why the usual rotating isn’t happening.)The whole thing isn’t quite as earth-shattering as it sounds—first, because it locks the image in only one way: upright, in portrait orientation. You can’t make it lock into widescreen mode. Furthermore, many apps don’t rotate with the phone to begin with. But when that day comes when you want to read in bed on your side with your head on the pillow, your iPhone will be ready. (Tap the button again to turn rotating back on.)

Brightness. Hallelujah! Here’s a screen-brightness slider. Drag the little white ball to change the screen brightness.

Sample Siri commands: “Make the screen brighter.” “Dim the screen.”

AirPlay Mirroring (

). The AirPlay button lets you send your iPhone’s video and audio to a wireless speaker system or TV—if you have an AirPlay receiver, of which the most famous is the Apple TV. Details are in TV Output.

). The AirPlay button lets you send your iPhone’s video and audio to a wireless speaker system or TV—if you have an AirPlay receiver, of which the most famous is the Apple TV. Details are in TV Output.AirDrop (

). AirDrop gives you a quick, effortless way to shoot photos, maps, web pages, and other stuff to nearby iPhones, iPads, iPod Touches, and even Macs. (See The Share Sheet for details.)

). AirDrop gives you a quick, effortless way to shoot photos, maps, web pages, and other stuff to nearby iPhones, iPads, iPod Touches, and even Macs. (See The Share Sheet for details.)On the Control Center, the AirDrop button isn’t an on/off switch like most of the other icons here. Instead it produces a pop-up menu of options that control whose i-gadgets can “see” your iPhone: Contacts Only (people in your address book), Everyone, or Receiving Off (nobody).

Night Shift (

). “Many studies have shown that exposure to bright blue light in the evening can affect your circadian rhythms and make it harder to fall asleep,” Apple’s website says. You can therefore tap this button to give your screen a warmer, less blue tint. (You can also set Night Shift to turn on near bedtime automatically; see Tip.)

). “Many studies have shown that exposure to bright blue light in the evening can affect your circadian rhythms and make it harder to fall asleep,” Apple’s website says. You can therefore tap this button to give your screen a warmer, less blue tint. (You can also set Night Shift to turn on near bedtime automatically; see Tip.)Sample Siri command: “Turn on Night Shift.”

Note

Truth is, there’s not much research that blue light from screens affects your circadian rhythm, let alone little screens like your phone. And the iPhone may not cut out enough blue to make much of a difference anyway. (If using a gadget before bed makes it harder to sleep, it’s more likely that it’s the brain stimulation of what you’re reading.) Sleep scientists have a more universally effective suggestion: Turn off your screens a couple of hours before bedtime.

Flashlight (

). Tap to turn on the iPhone’s “flashlight”—actually the LED lamp on the back that usually serves as the camera flash. Knowing that a source of good, clean light is a few touches away makes a huge difference if you’re trying to read in the dark, find your way along a path at night, or fiddle with wires behind your desk.

). Tap to turn on the iPhone’s “flashlight”—actually the LED lamp on the back that usually serves as the camera flash. Knowing that a source of good, clean light is a few touches away makes a huge difference if you’re trying to read in the dark, find your way along a path at night, or fiddle with wires behind your desk.Timer (

). Tap to open the Clock app—specifically, the Timer mode, which counts down to zero. Apple figures you might appreciate having direct access to it when you’re cooking, for example, or waiting for your hair color to set.

). Tap to open the Clock app—specifically, the Timer mode, which counts down to zero. Apple figures you might appreciate having direct access to it when you’re cooking, for example, or waiting for your hair color to set.Sample Siri commands: “Open the Timer.” Or, better yet, bypass the Clock and Timer apps altogether: “Start the timer for three minutes.” “Count down from six minutes.” (Siri counts down right there on the Siri screen.)

Calculator (

). Tap to open the Calculator app—a handy shortcut if it’s your turn to figure out how to divide up the restaurant bill.

). Tap to open the Calculator app—a handy shortcut if it’s your turn to figure out how to divide up the restaurant bill.Sample Siri commands: “Open the calculator.” Or, better yet, without opening any app: “What’s a hundred and six divided by five?”

Camera (

). Tap to jump directly into the Camera app. Because photo ops don’t wait around.

). Tap to jump directly into the Camera app. Because photo ops don’t wait around.Sample Siri commands: “Take a picture.” “Open the camera.”

On the Playback screen of the Control Center, you get these options:

Music information. Now that the playback buttons are on a separate screen, there’s room for some information about the current song, and even a photo of the album.

Playback controls (

). These controls govern playback in whatever app is playing music or podcasts in the background: the Music app, Pandora, Spotify, whatever it is. You can skip a horrible song quickly and efficiently without having to interrupt what you’re doing, or pause the music to chat with a colleague. (Tap the song name to open whatever app is playing.)

). These controls govern playback in whatever app is playing music or podcasts in the background: the Music app, Pandora, Spotify, whatever it is. You can skip a horrible song quickly and efficiently without having to interrupt what you’re doing, or pause the music to chat with a colleague. (Tap the song name to open whatever app is playing.)You also get a scrubber bar that shows where you are in the song, the name of the song and the performer, and the album name. And, of course, there’s a volume slider. It lets you make big volume jumps faster than you can by pressing the volume buttons on the side of the phone.

Sample Siri commands: “Pause the music.” “Skip to the next song.” “Play some Billy Joel.”

Audio Output. At the very bottom of this screen, you can choose which speaker source you want for playback. It always lists iPhone (the built-in speakers), but it may also list things like a Bluetooth speaker, earbuds, or AirPlay, which sends music or video to a wireless speaker system or TV (see Switching Among Speakers).

The Control Center closes when any of these things happen:

You tap the Timer, Calculator, or Camera button.

You tap or drag downward from any spot above the Control Center (the dimmed background of the screen).

You press the Home button.

Note

In some apps, swiping up doesn’t open the Control Center on the first try, much to your probable bafflement. Instead, swiping up just makes a tiny  tab appear at the edge of the screen. (You’ll see this behavior whenever the status bar—the strip at the top that shows the time and battery gauge—is hidden, as can happen in the full-screen modes of iBooks, Maps, Videos, and so on. It also happens in the Camera.)

tab appear at the edge of the screen. (You’ll see this behavior whenever the status bar—the strip at the top that shows the time and battery gauge—is hidden, as can happen in the full-screen modes of iBooks, Maps, Videos, and so on. It also happens in the Camera.)

In those situations, Apple is trying to protect you from opening the Control Center accidentally—for example, when what you really wanted to do was scroll the image up. No big deal; once the  appears, swipe up a second time to open the Control Center panel.

appears, swipe up a second time to open the Control Center panel.

If you find yourself opening the Control Center accidentally—when playing games, for example—you can turn it off. Open Settings→Control Center. Turn off Access Within Apps. Now swiping up opens the Control Center only at the Home screen. (You can also turn off Access on Lock Screen here, to make sure the Control Center never appears when the phone is asleep.)

Passcode (or Fingerprint) Protection

Like any smartphone, the iPhone offers a first line of defense for a phone that winds up in the wrong hands. It’s designed to keep your stuff private from other people in the house or the office, or to protect your information in case you lose the iPhone. If you don’t know the passcode or don’t have the right fingerprint, you can’t use the iPhone (except for limited tasks like taking a photo or using Siri).

About half of iPhone owners don’t bother setting up a passcode to protect the phone. Maybe they never set the thing down in public, so they don’t worry about thieves. Or maybe there’s just not that much personal information on the phone—and meanwhile, having to enter a passcode every time you wake the phone can get to be a profound hassle.

Tip

Besides—if you ever do lose your phone, you can put a passcode on it by remote control; see page 531.

The other half of people reason that the inconvenience of entering a passcode many times a day is a small price to pay for the knowledge that nobody can get into your stuff if you lose your phone.

If you think your phone is worth protecting, here’s how to set up a passcode—and, if you have an iPhone 5s or later model, how to use the fingerprint reader instead.

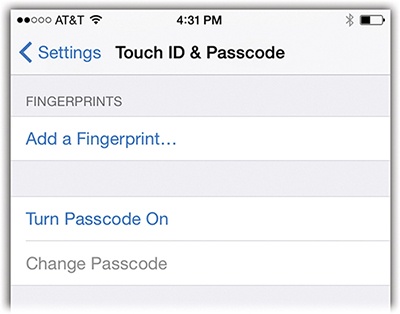

Setting Up a Passcode

If you didn’t already create a phone passcode the first time you turned your iPhone on (see Tip), here’s how to do it. (And just because you’re an iPhone 5s-or-later owner, don’t be smug; you have to create a passcode even if you plan to use the fingerprint reader. As a backup.)

Open Settings→Touch ID & Passcode. (On the 5c, it’s just called Passcode Lock.)

iOS 10 proposes a longer string of numbers than iOS once did, for greater security (six digits instead of four). But you can tap Passcode Options if you’d prefer a four-digit number, or a full-blown alphanumeric password of any length.

You’re asked to type the passcode you want, either on the number keypad (for number codes) or the alphabet keyboard. You’re asked to do it again to make sure you didn’t make a typo.

Note

Don’t kid around with this passcode. If you forget the iPhone code, you’ll have to restore your iPhone (Tip), which wipes out everything on it. You’ve probably still got most of the data on your computer or backed up on iCloud, of course (music, video, contacts, calendar), but you may lose text messages, mail, and so on.

Once you confirm your passcode, you return to the Passcode Lock screen. Here you have a few more options.

The Require Passcode option lets you specify how quickly the password is requested before locking somebody out: immediately after the iPhone wakes or 1, 15, 30, 60, or 240 minutes later. (Those options are a convenience to you, so you can quickly check your calendar or missed messages without having to enter the passcode—while still protecting your data from, for example, evildoers who pick up your iPhone while you’re out getting coffee.)

Certain features are accessible on the Lock screen even before you’ve entered your password: the Today and Notifications tabs of the Notification Center; Siri, Wallet, Home Control, and Reply with Message (the ability to reply to text messages right from their notification bubble).

These are huge conveniences, but also, technically, a security risk. Somebody who finds your phone on your desk could, for example, blindly voice-dial your colleagues or use Siri to send a text. If you turn these switches off, then nobody can use these features until after entering the password (or using your fingerprint).

Finally, here is Erase Data—an option that’s scary and reassuring at the same time. When this option is on, then if someone makes 10 incorrect guesses at your passcode, your iPhone erases itself. It’s assuming that some lowlife burglar is trying to crack into it to have a look at all your personal data.

This option, a pertinent one for professional people, provides potent protection from patient password prospectors.

Note

Even when the phone is locked and the password unguessable, a tiny blue Emergency Call button still appears on the Unlock screen. It’s there just in case you’ve been conked on the head by a vase, you can’t remember your own password, and you need to call 911.

And that is all. From now on, each time you wake your iPhone (if it’s not within the window of repeat visits you established), you’re asked for your password.

Fingerprint Security (Touch ID)

If you have an iPhone 5s or later, you have the option of using a more secure and convenient kind of “passcode”: your fingertip.

The lens built right into the Home button (clever!) reads your finger at any angle. It can’t be faked out by a plastic finger or even a chopped-off finger. You can teach it to recognize up to five fingerprints; they can all be yours, or some can belong to other people you trust.

Before you can use your fingertip as a password, though, you have to teach the phone to recognize it. Here’s how that goes:

Create a passcode. You can’t use a fingerprint instead of a passcode; you can only use a fingerprint in addition to one. You’ll still need a passcode from time to time to keep the phone’s security tight. For example, you need to enter your passcode if you can’t make your fingerprint work (maybe it got encased in acrylic in a hideous crafts accident), or if you restart the phone, or if you haven’t used the phone in 48 hours or more.

So open Settings→Touch ID & Passcode and create a password, as already described.

Teach a fingerprint. At the top of the Touch ID & Passcode screen, you see the on/off switches for the three things your fingerprint can do: It can unlock the phone (iPhone Unlock), pay for things (Apple Pay), and it can serve as your password when you buy books, music, apps, and videos from Apple’s online stores (iTunes & App Store).

But what you really want to tap here, of course, is Add a Fingerprint.

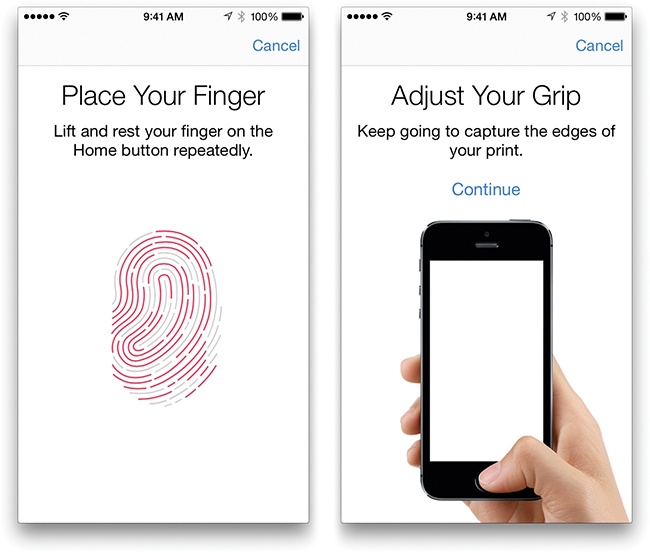

Now comes the cool part. Place the finger you want to train onto the Home button—your thumb or index finger are the most logical candidates. You’re asked to touch it to the Home button over and over, maybe six times. Each time, the gray lines of the onscreen fingerprint darken a little more.

Once you’ve filled in the fingerprint, you see the Adjust Your Grip screen. Tap Continue. Now, the iPhone wants you to touch the Home button another few times, this time tipping the finger a little each time so the sensor gets a better view of your finger’s edges.

Once that’s done, the screen says “Success!”

You are now ready to start using the fingerprint. Try it: Put the phone to sleep. Then wake it (press the Sleep switch or press the Home button), and leave your finger on the Home button for about a second. The phone reads your fingerprint and instantly unlocks itself.

And now, a few notes about using your fingerprint as a password:

Yes, you can touch your finger to the Home button at the Lock screen. But you can also touch it at any Enter Passcode screen.

Suppose, for example, that your Lock screen shows that you missed a text message. And you want to reply. Well, you can swipe across that notification to open it in its native habitat—the Messages app—but first you’re shown the Enter Passcode screen. Ignore that. Just touch the Home button with the finger whose print you recorded.

Apple says the image of your fingerprint is encrypted and stored in the iPhone’s processor chip. It’s never transmitted anywhere, it never goes online, and it’s never collected by Apple.

If you return to the Touch ID & Passcode screens, you can tap Add a Fingerprint again to teach your phone to recognize a second finger. And a third, fourth, and fifth.

The five “registered” fingerprints don’t all have to belong to you. If you share the phone with a spouse or a child, for example, that special somebody can use up some of the fingerprint slots.

On the other hand, it makes a lot of sense to register the same finger several times. You’ll be amazed at how much faster and more reliably your thumb (for example) is recognized if you’ve trained it as several different “fingerprints.”

To rename a fingerprint, tap its current name (“Finger 1” or whatever). To delete one, tap its name and then tap Delete Fingerprint. (You can figure out which finger label is which by touching the Home button; the corresponding label blinks. Sweet!)

You can register your toes instead of fingers, if that’s helpful. Or even patches of your wrist or arm, if you’re patient (and weird).

The Touch ID scanner may have trouble recognizing your touch if your finger is wet, greasy, or scarred.

The iPhone’s finger reader isn’t just a camera; it doesn’t just look for the image of your fingerprint. It’s actually measuring the tiny differences in electrical conductivity between the raised parts of your fingerprint (which aren’t conductive) and the skin just beneath the surface (which is). That’s why a plastic finger won’t work—and even your own finger won’t work if it’s been chopped off (or if you’ve passed away).

Fingerprints for Apps, Websites, and Apple Pay

So if your fingerprint is such a great solution to password overload, how come it works only to unlock the phone and to buy stuff from Apple’s online stores? Wouldn’t it be great if your fingerprint could also log you into secure websites? Or serve as your ID when you buy stuff online?

That dream is finally becoming a reality. Software companies can now use your Touch ID fingerprint to log into their apps. Mint (for checking your personal finances), Evernote (for storing notes, pictures, and to-do lists), Amazon (for buying stuff), and other apps now permit you to substitute a fingerprint touch for typing a password.

What’s really wild is that password-storing apps like 1Password and LastPass have been updated, too. Those apps are designed to memorize your passwords for all sites on the web, of every type—and now you can use your fingerprint to unlock them.

Moreover, your fingerprint is now the key to the magical door of Apple Pay, the wireless pay-with-your-iPhone technology described in Apple Pay.

All of this is great news. Most of us would be happy if we never, ever had to type in another password.