I. BACKSTORY

A. HISTORY

Traditionally France was the dominant mainland power of continental Europe. Its principal maritime opponent until the beginning of the twentieth century was Great Britain. Like Britain, France had become a world power through the acquisition of a vast overseas empire, but the French navy (latterly known as the Marine Nationale but still often referred to as “La Royale”) lived in the shadow of Britain’s Royal Navy, even during those periods when French armies held sway over the continent. Failure to dominate the seas thwarted broader French political ambitions.

There were periods when the Marine Nationale attempted to contest British maritime supremacy ship for ship, but in the latter half of the nineteenth century policy shifted toward a two-tier strategy: the defense of the French coasts and the prevention of blockade on the one hand, and the construction of powerful long-range cruisers which could disrupt British commerce on the high seas on the other hand. This asymmetric strategy is closely associated with the thinking of Admiral Hyacinthe Aube and a group of admirals known as the Jeune École (young school). Aube and his associates were of the view that squadrons of British battleships attempting to blockade French ports could best be countered by employing large numbers of cheap surface ships and submersibles (la poussière navale—literally, “naval dust”) armed with torpedoes, which would operate close to their base ports under the cover of powerful batteries of coast defense guns.

These ideas became irresistible for economic reasons during the 1880s and 1890s, when the British Royal Navy of the late Victorian period became a force capable of defeating the fleets of any two of the continental powers at sea. With the Entente Cordiale of 1904, Britain became a potential ally against a newly resurgent Germany, and the Marine Nationale again began to harbor ambitions of maritime domination exercised by a conventional fleet of modern battleships. However, those ambitions were now limited to the Mediterranean, which Britain was increasingly happy to abandon to French hegemony to enable her own fleet to be concentrated in the North Sea against the German Hochseeflotte (High Seas Fleet). From 1900 onward France began to invest heavily in infrastructure in the Mediterranean, creating a base at Bizerte (Tunisia), which it envisaged would rival Toulon in size and capacity—it would be referred to by some as ‘le Toulon africain’—and which would enable France to dominate not only the western Mediterranean basin but the central and eastern Mediterranean too, while at the same time ensuring the security of sea lines of communication with her colonies in North Africa and the Middle East. The Marine Nationale followed the construction of six powerful turbine-powered “semidreadnoughts” of the Danton class (1906–1911) with its first dreadnoughts, the four-ship Courbet class laid down in 1910–1911. These were closely followed by three similar ships of the Bretagne class, and the Navy Act (Statut Naval) of 1912 stipulated a fleet of no fewer than twenty-eight modern battleships to be completed by 1920, together with ten scout cruisers and fifty-two oceangoing destroyers.

All this came to a halt when war broke out in August 1914. Early reverses on land led all military and industrial efforts to be refocused on the army. Work in the west coast dockyards and shipyards was restricted to the completion of those ships already launched, and the Mediterranean yards were fully occupied with the maintenance and repairs of the large French fleet operating there.

In 1918 France’s naval infrastructure was in such a poor state that it was impossible to contemplate a new naval program before 1921–1922. In the interim, studies were carried out for a new generation of cruisers, flotilla craft, and submarines, and serious consideration was given to completing the battleships of the Normandie class launched 1914–1916 to revised plans. While these studies were under way, the Washington Conference (November 1921–February 1922) intervened. The French negotiators, who had been instructed to push for 350,000 tons with a fallback position of 280,000 tons, which would have given parity with Japan, were shocked to be offered only 175,000 tons of capital ship tonnage and parity with Italy. However, in a meeting of the Conseil de la Défense Nationale on 28 December it was proposed that France should opt for a purely defensive fleet, and it was suggested that for the not-unreasonable sum of 500 million francs per year, 330,000 tons of light surface ships and 90,000 tons of submarines could be built over a period of ten years. These views were accepted, and the two-year 1922 naval program was fixed at three 8,000-ton cruisers (Duguay-Trouin class), six ships of a new 2,400-ton superdestroyer type (the contre-torpilleurs of the Jaguar class), twelve large 1,500-ton fleet torpedo boats (Bourrasque class), six 1,150-ton patrol submarines (Requin class), and twelve 600-ton coastal defense submarines.

Italy was now seen as France’s main rival for influence in the Mediterranean, and the naval programs of both countries proceeded in parallel throughout the 1920s, with a similar focus on 10,000-ton treaty cruisers, fast flotilla craft, and submarines, with the French maintaining a slight edge on numbers of ships laid down. This changed when in 1928 the German Republic laid down the first of three Panzerschiffe armed with 28-cm guns. The Marine Nationale again seriously contemplated building new battleships to counter the German ships, which led to the laying down of Dunkerque and her near-sister Strasbourg during the early 1930s. By the mid-1930s France faced a possible naval war on two fronts, against Germany and Italy, and the construction of flotilla craft and submarines was virtually halted in favor of a new program of 35,000-ton battleships. Only one of these had been launched by September 1939, when the Marine Nationale was compelled to focus building efforts on those ships that could be completed within two years; many other ships authorized in 1938 would be canceled.

B. MISSION

The key missions of the Marine Nationale were essentially defensive: to protect the coastline, ports, and harbors of metropolitan France; to secure the integrity of the colonies (“la France d’outre-mer”); and to protect the sea lines of communication between France and her overseas empire. Unlike the British and the Americans, the French never envisaged sending an expeditionary fleet to dominate waters far from home. All the key French naval bases were protected by powerful shore batteries, and an unusual parallel command structure meant that there were naval forces composed of torpedo boats, coastal submarines, and land-based aircraft specifically assigned to each of the five régions maritimes (maritime regions) for coastal defense under the command of a senior admiral whose headquarters were ashore. These were not only independent of the seagoing forces, which were generally organized as escadres (squadrons) under a senior admiral directly responsible at an operational level to the Admiral of the Fleet but were generally funded from a separate budget under the title défense des côtes (coast defense).1

Following the Treaty of Versailles, which neutralized the German navy, and then the Washington Conference, Italy became France’s primary political and military rival and the western Mediterranean the most likely theater of operations. The cruisers and contre-torpilleurs laid down during the 1920s were intended to contest these seas; they were fast, lightly protected, and hard-hitting with long-range torpedoes complementing their medium-caliber guns. They could intervene against Italian forces attempting to cut lines of communication with French North Africa, and they could be used aggressively against Italy’s own lines of communication in the central Mediterranean. The slow, elderly battle squadron, escorted by a new generation of fleet torpedo boats, served essentially as a back-up force on which the light forces could fall back for support if hard-pressed. The French, like their Italian counterparts, had reservations about the ability of these ships to operate in narrow seas dominated by increasingly capable land-based aircraft.

The rearmament of Germany, beginning with the laying down in 1928 of the first of three Panzerschiffe, led to a new type of ship and to a major change both in strategy and the pattern of deployments. The fast battleships Dunkerque and Strasbourg and the second generation of contre-torpilleurs were intended to form hunting groups to protect French shipping in the Atlantic from German surface raiders. The result was the formation of the elite Force de Raid at Brest.

The French naval situation, which had deteriorated significantly with the threat of a war on two fronts, was considerably eased by the revival of the Anglo-French entente in the two years immediately preceding the Second World War. The British took on responsibility for the North Atlantic and the eastern Mediterranean while the French had primary responsibility for the western Mediterranean and the waters off West Africa. The French provided support in the North Atlantic while British forces operated with the French in a composite antiraider force known as “Force X” out of Dakar. When it appeared that Italy might enter the war in the early summer of 1940, a French squadron was dispatched to operate in the eastern Mediterranean under British command, and the Force de Raid moved to Mers el-Kebir in French North Africa.

When the French armies in Belgium and northern France collapsed in May–June 1940, the navy was experienced and undefeated, and eager to get to grips with the Italian Regia Marina. Italy’s late entry into the war frustrated the strategy of the Marine Nationale, which never had the opportunity to carry out the primary missions for which its ships had been designed.

II. ORGANIZATION

A. COMMAND STRUCTURE

1. Administration

The French command structure had a well-conceived framework that was considerably refined during the 1930s. It was in the form of a pyramid, at the top of which was a minister for national defense, who was responsible for drawing up national objectives and putting the means for achieving those objectives at the disposal of the commanders in chief of the respective branches of the armed forces. The minister was seconded by a military chief of the General Staff for National Defense, an executive body comprising the ministers and the senior officers of the armed services charged with coordinating studies for the strategic preparation for war and for drawing up plans for operations and mobilization. There was also a purely military advisory body, the Conseil Supérieur de la Défense Nationale (CSDN), and a war committee (Comité de Guerre).

The next tier comprised the general staffs for each of the services; each service had its own advisory body, or Conseil Supérieur, at this level. The chief of the Naval General Staff (NGS) was Admiral François Darlan, who was an ex officio member of the CSDN and the war committee. In 1939, after Darlan had—in accordance with notoriously rigid British protocol—found himself “behind a column and a Chinese admiral” at the coronation of King George VI, Darlan created for himself the rank of Admiral of the Fleet and the position of commander in chief of the French Maritime Forces, which effectively gave him the necessary seniority to engage with the British First Sea Lord, Admiral Dudley Pound, and a greater degree of power and influence than Pound within his own country. As commander in chief of the French Maritime Forces, Darlan now exercised direct command over the commanders in chief of the operational theaters, the seagoing forces, and the naval commanding officers outside the régions maritimes.

Darlan’s personal staff comprised Vice Admiral Maurice Le Luc and two captains, and he delegated his powers as chief of the NGS to Vice Admiral François Michelier, who was directly responsible to the navy minister. During the late 1930s a new naval command center was built outside Paris at Maintenon (near Chartres). Known as the Amirauté Française, it was generally considered a model of organization; it enjoyed excellent communications with the fleet and the regional naval headquarters and was divided internally into three main departments: intelligence, operations, and special services. It served to increase Darlan’s autonomy from the other services until June 1940, when the Amirauté was evacuated to Vichy via Bordeaux. Darlan’s power and influence then became incontestable when he agreed to become “number three” in Marshal Henri Pétain’s newly formed national government.

In 1939 France and French North Africa were divided into five administrative sectors known as régions maritimes (maritime regions), each of which was commanded by a senior admiral known as the préfet maritime, and who was directly responsible to the navy minister:

• 1st Maritime Region: HQ Dunkerque

• 2nd Maritime Region: HQ Brest

• 3rd Maritime Region: HQ Toulon

• 4th Maritime Region: HQ Bizerte

• 5th Maritime Region: HQ Lorient

Each préfet maritime was responsible for coastal defense in his sector and had under his command local naval forces including torpedo boats, coastal submarines, harbor defense units, coast defense artillery and antiaircraft batteries, naval land-based aircraft for reconnaissance, bombing and torpedo attack, and fighters/bombers placed at the navy’s disposition by the air force.

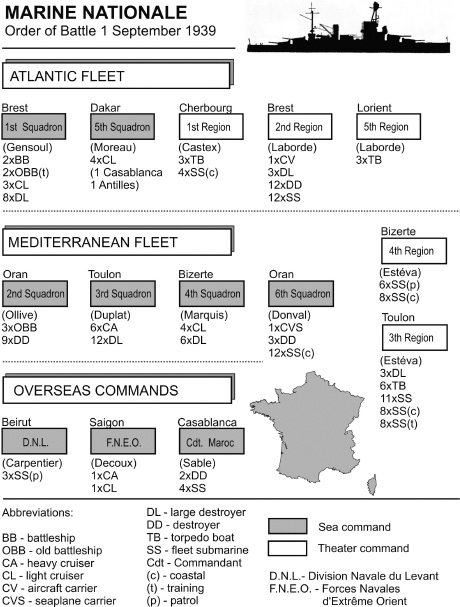

When war broke out in September 1939, shore-based theater commanders were appointed to oversee naval operations in the three key operational areas: the 5th Maritime Region was combined with the 2nd under Admiral West, and the 3rd and 4th regions were combined under Admiral South. Additional theater commanders were subsequently appointed to cover the South Atlantic and the West Indies. These commands were as follows:

• North (North Sea and Channel): Vice Admiral Raoul Castex, HQ Dunkerque

• West (North Atlantic): Vice Admiral Jean de Laborde, HQ Brest

• South (Mediterranean): Vice Admiral Jean-Pierre Estéva, HQ Toulon, then Bizerte

• South Atlantic: Vice Admiral Emmanuel Ollive, HQ Casablanca

• Western Atlantic: Vice Admiral Georges Robert, HQ High Commission French Antilles

The commander in chief of the Forces Navales d’Extrême-Orient (FNEO–Far East), Vice Admiral Jean Decoux, was also the theater commander.

The principal seagoing forces at the outbreak of war were the Atlantic Fleet based at Brest and the Mediterranean Fleet based at Toulon, Oran, and Bizerte. The Flotte de l’Atlantique (Atlantic Fleet), commanded by Squadron Vice Admiral Marcel Gensoul, initially comprised the 1st Squadron (Force de Raid): the two modern battleships Dunkerque and Strasbourg, a division of light cruisers, and three divisions of the latest contre-torpilleurs. The Flotte de la Méditerranée (Mediterranean Fleet) comprised three squadrons: the 2nd, commanded by Squadron Vice Admiral Ollive and based at Toulon, comprised the three older battleships and their fleet torpedo boat escorts; the 3rd comprised two divisions of 10,000-ton cruisers, and three divisions of contretorpilleurs and was likewise based at Toulon. In the build-up to the war, a second fast squadron (4th Escadre) was formed at Bizerte with a light cruiser division and three divisions of contre-torpilleurs with a view to threatening Italian sea lines of communication with North Africa. Placed under the command of Rear-Admiral André Marquis this grouping was known as the Forces Légères d’Attaque (light attack forces). All the submarines except Surcouf (under direct command of Darlan) and most of the older fleet torpedo boats were assigned to the régions maritimes.

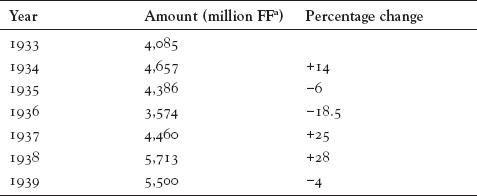

In the seven years leading up to war, the navy’s budget increased by 35 percent. Budget estimates for 1933–1939 are provided in table 1.1.

TABLE 1.1 Budgetary Estimates for the Marine Nationale 1933–1939

Note: Between 1929 and 1939 the total budget for the armed services amounted to 105,000 million FF. The distribution between the individual services was as follows: Armée de Terre, 52%; Armée de l’Air, 27%; Marine, 21%.

a Exchange rate 1937: 100 million FF = £0.8 million / US$3.9 million.

Sources: Espagnac du Ravay, Vingt ans de politique navale (1919–39) (Grenoble: B. Arthaud, 1941).

French naval officers belonged to one of two branches, each of which had its own training procedures and ranking system. The officiers de Marine (also known as the Grand Corps) were selected for their leadership qualities and prepared for command, first as heads of the various departments on board ship, and ultimately as captains of ships or senior staff officers; their training was initially multidisciplinary, with specialization after the first four years. The other branch, referred to as officers de la Marine, included engineering, medical, and supply officers. Of the ingénieurs-mécaniciens, one-third were selected by competition, the other two-thirds on the basis of their technical qualifications.

Officiers de Marine trained at the prestigious École Navale, which from 1935 was housed in an impressive new building at Brest with a colonnaded facade of white stone 180 m long. After two years of formal studies at the École Navale the officer cadets were sent on a ten-month world cruise (October to July each year) aboard the purpose-built training cruiser Jeanne d’Arc. Completed in 1931, displacing 8,000 tons, and armed with eight 155-mm guns in twin turrets, Jeanne d’Arc could accommodate up to 156 midshipmen. The trainee officers were then posted to a foreign station in the Far East, the Indian Ocean, or West/North Africa for a year before attending one of six specialist schools: Gunnery Officer, Communications, Torpedo, Submarine Navigation (all at Toulon), Officer of Marines (at Lorient), or Naval Aviation (at Versailles, then at Avord and Hourtin). The duration of the courses at these schools was generally three to five months, after which the trainees were accorded the rank of lieutenant and assigned to ships.

Access to the higher ranks was via a one-year course at the naval war college in Paris. Promotion to lieutenant commander was normally at age thirty-eight to forty; an officer of this rank might command a torpedo boat or a submarine, or be appointed to an admiral’s staff. A strong performance at this level might lead to promotion to commander at forty-six to fifty years of age and to command of a light cruiser, while officers selected for promotion to captain might command a heavy cruiser or capital ship. From the 118 captains, 32 would be selected for promotion to rear admiral; eighteen months of sea command was a minimum requirement for promotion to this rank. Of these 32, 16 would rise to the rank of vice admiral, the highest rank available. A rear admiral might command a cruiser division or destroyer flotilla, or become the senior admiral ashore outside the five maritime regions; a vice admiral would command a squadron or an operational theater—in which case he would generally be designated vice-amiral d’escadre and have a fourth star on his flag—or become préfet maritime for one of the five regions.

Prospective engineering officers received their education in a school adjacent to the École Navale in Brest. On completion of their studies, they would, like their counterparts at the École Navale, embark on the Jeanne d’Arc for a world training cruise. They would subsequently be assigned as junior engineering officers to larger surface ships. Following promotion they would then be appointed as head of the engineering department of smaller warships or submarines. At age forty, the engineering officer would normally be promoted to ingénieur principal (equivalent to lieutenant commander rank) and would become chief engineer on a major ship such as a cruiser or battleship. Further promotion would lead to shore appointments in supervisory, training, or inspection capacities.

Other ranks first received general training and were then assigned to one of a dozen specialist schools serving the different branches, such as gunnery, torpedo, or communications, most of which were located at Brest or Toulon. Recruitment to the navy relied heavily on the traditional maritime regions, particularly Brittany, where fishing continued to be a major industry. These men were hardy, committed seamen with a natural sense of the demanding nature of their environment. Unfortunately for the Marine Nationale, the massive expansion of the active fleet during the late 1930s came at a time of much-improved pay and conditions for workers in the dockyards and industries ashore, and a shortfall in recruitment had to be compensated for by large-scale mobilization in 1939. Following the Armistice of June 1940, reservists, who accounted for up to one-third of the crews in some ships, expected an immediate discharge. Many were anxious to be reunited with wives and families now living in the occupied zone, from whom they were receiving no letters. Potentially mutinous behavior aboard the older battleships was quashed at Mers el-Kebir in June 1940, but the problem would reemerge in early July at Dakar, where many crossed the gangways with their kitbags, leaving the crews of some ships too depleted to sail.

3. Intelligence

The French naval intelligence service was known during the 1930s as EMG/2 (État-Major/Deuxième Bureau) and became FMF/2 (Forces Maritimes Françaises/Deuxième Bureau) on the outbreak of war. It was centralized at Maintenon, which had excellent communications both with the fleet and with naval command centers ashore but was also represented in foreign embassies, where naval personnel were tasked with the gathering of intelligence from local sources. The Deuxième Bureau had acquired a high reputation for cryptoanalysis during the First World War and prior to the Second World War had acquired manuals for the German army’s Enigma cipher system. However, tactical intelligence appears to have relied heavily on shipboard and shore-based reconnaissance, and radio-direction finding (RDF) techniques were likewise generally focused on ships at sea rather than at land sites. This aspect of operations was less well developed than in the United Kingdom.

After the Armistice of 1940 the Deuxième Bureau was disbanded and replaced by a centre d’information gouvernemental (CIG) under Darlan. The new service was overtly tasked with rooting out communist sympathizers and resistance factions but was also secretly engaged in counterespionage operations.

During 1942 the Free French government created its own intelligence service, the Bureau Central de Renseignements et d’Action (BCRA). This organization was subsequently reformed under various different names as a result of ongoing internal political maneuvering

The focus on political as opposed to military intelligence operations after the fall of France was to have major repercussions for the navy. Ship-borne and land-based reconnaissance aircraft were plentiful and of modern design, and their naval crews were well trained for operations over the water. However, the signals intelligence which would have “cued in” reconnaissance aircraft before contact was often lacking, and the French were twice surprised by hostile forces at Mers el-Kebir in June 1940, then at Dakar in September 1940, and again at Casablanca in November 1942.

B. DOCTRINE

1. Surface Warfare

With the rapid buildup of the German navy following Hitler’s renunciation of the Treaty of Versailles, the surface warfare doctrine of the Marine Nationale was subjected to a major revision during the mid-1930s to take account of the two very different major operational theaters: the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean. In the North Atlantic the main threat was posed by German surface raiders—there was as yet no U-boat fleet worthy of consideration, although the German signature to the League of Nations protocol prohibiting unrestricted warfare against merchant shipping did little to allay French fears for the longer term. The Atlantic Squadron (later Fleet) was built around the two new fast battleships Dunkerque and Strasbourg, three modern light cruisers, and eight of the latest contre-torpilleurs of the Mogador and Le Fantasque classes, which were tasked with scouting for the new battleships and designed with North Atlantic operations in mind. The battleships and light cruisers were each designed to operate three modern Loire 130 reconnaissance floatplanes, which would enable a hunting group formed from the elite Force de Raid to locate its prey. The 330-mm guns of the battleships had a 35-degree angle of elevation and a maximum range of 41,700 m, and were all mounted forward to enable the ships to engage effectively in a stern chase.

The relatively confined waters of the western and central Mediterranean required different ships and different tactics. Operations were expected to be of short duration, comprising fleeting engagements characterized by high-speed maneuvers: raids on enemy shipping and coasts, and interventions to prevent similar raids by enemy forces. The design of the ships built for these purposes during the 1920s and 1930s emphasized high performance (in particular speed and gun power) at the expense of range and endurance. At the center of these forces were the 10,000-ton cruisers and the modern light cruisers, operating in three-ship divisions. The powerful contre-torpilleurs, most of which were armed with 138-mm guns, were intended for operations on the flank. When operating in support of the fleet, their principal task was to penetrate the outer screen of an enemy force and transmit information on its composition, heading, and so forth while at the same time providing an impenetrable screen for friendly cruiser and battle divisions. Like the cruiser divisions, the contre-torpilleurs operated in tactical divisions of three ships and by 1939 were equipped with shells containing colored dye that enabled each ship to spot its own fall of shot.

With the commissioning of Dunkerque and Strasbourg during the late 1930s the older battle division, comprising the three Bretagne-class ships, transferred from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean. Although slow and outdated, they provided a strong core on which the light forces could fall back if hard-pressed. The Bretagnes were to be replaced by fast modern 35,000-ton units from 1940, and a new generation of fleet torpedo boats to accompany them was already on the stocks. Had it been completed, the new battle fleet would undoubtedly have played a much more dynamic and focal role in French surface warfare tactics in the Mediterranean.

2. Aviation

The French were entitled to 60,000 tons of carrier construction under the terms of the Washington Treaty and originally intended to build up to this level. One of the incomplete battleships of the Normandie class, Béarn, was duly converted into a forty-plane carrier with a function similar to that of contemporary British carriers. Operating in conjunction with the battle fleet, she was to provide fighters for fleet air defense, two- or three-seat aircraft for reconnaissance and spotting, and a torpedo attack capability to slow the enemy fleet and bring it to battle. Additional purpose-built ships of 18,000–20,000 tons were projected, but these failed to materialize, first for budgetary reasons and then because of the formation of the Air Ministry in 1928, which acquired almost total control of naval air assets. The carrier also lost favor as a fleet unit with the advent of more capable land-based aircraft during the 1930s, and there were influential officers in the Marine Nationale who came to believe that carrier operations in the western Mediterranean were no longer feasible, and that carriers were useful only for projecting air power into the more open expanses of the North Atlantic.

By the late 1930s, the Béarn was seriously in need of replacement, and although modernized in 1935 and redeployed to Brest, she was too slow to operate with the new fast battleships. The first of two modern 18,000-ton fleet carriers was laid down in 1938 at St. Nazaire, and a new generation of monoplane fighter and bomber aircraft was ordered, some from the United States. Béarn’s air squadrons were disembarked and were in the process of being reequipped in 1939 when war broke out. The newly equipped air squadrons remained ashore; they almost certainly would have operated from Béarn only for deck trials and work-up before being embarked in the new carrier Joffre in 1942.

As a cheaper alternative to the fully fledged carrier, the French developed the concept of the transport d’aviation, a 10,000-ton mobile seaplane base capable of transporting and operating squadrons of large seaplanes armed with torpedoes handled by cranes and launched from the surface and smaller reconnaissance floatplanes and float fighters launched by catapult. Although regarded as successful in her primary role, Commandant Teste was considered too slow and too vulnerable to operate with the fleet, and only a single unit was completed. In December 1939 her air group was redeployed ashore, and the ship was used as an aircraft transport between France and North Africa.

The navy regained control of naval aviation in 1936. Besides embarked aircraft, the navy operated large numbers of reconnaissance aircraft from its own shore bases, and new torpedo strike aircraft became available from mid-1939.

3. Antisubmarine

In the early years following the First World War, the Marine Nationale accorded antisubmarine (A/S) warfare the same degree of priority as did the British Royal Navy. In 1918, 136 A/S depth-charge throwers (DCT) were purchased from Thornycroft, and programs were begun to develop effective underwater sensors. The flotilla craft of the 1922 naval program all had space provided for retractable ultrasonic detection devices and their associated consoles, and were designed to accommodate stern-launched 200-kg depth charges, four DCTs, and Italian Ginocchio towed antisubmarine torpedoes. To accommodate the latter and their associated handling gear on the quarterdeck, the depth charges were carried in two stern tunnels and launched using a continuous chain mechanism at the rate of one every six seconds. These early units of the Jaguar and Bourrasque classes and their immediate successors carried twelve depth charges in the two tunnels, together with eight and four reloads, respectively, in a below-decks magazine aft. Later contre-torpilleurs had sixteen in the tunnels with eight reloads.

Doctrine stipulated that the ship turn toward the last known position of the submarine contact and release four 200-kg depth charges set to a depth of 50 m. In theory this created a “killing ground” 240 m long and 60 m wide; this band could be widened if depth charge throwers were also used. For the second pass, the depth setting was to be 100 m. Sufficient charges were provided for between four and six passes, depending on the size of the ship.

Two factors undermined these ambitious plans. All of the early interwar flotilla craft suffered from topweight and stability problems. Plans to fit four Thornycroft DCTs were quickly abandoned; some ships received two, but most had only the deck reinforcements necessary for wartime installation. The Ginocchio torpedoes and their handling gear also generated additional top weight, and technical problems with these devices meant that their development was suspended in 1933.

The other even more important factor was the failure to develop a successful underwater sensor. From the late 1920s to 1939 the French experimented with a variety of ultrasonic “pingers” and passive hydrophone arrays without ever producing a sensor that could reliably detect a submarine while the ship was under way. In 1939 some fleet torpedo boats were fitted with the French-developed SS 1 ultrasonic device, for which two torpedoes had to be landed as compensation. Installation in other ships was suspended in March 1940 when the SS 1 proved ineffectual. Fortunately a technology exchange with Britain during 1939 resulted in access to the infinitely more capable British Asdic in return for French shell colorant technology. Sixteen sets were ordered in May 1939, and delivery began in August; a further fifty sets were ordered in October. In French service the device was known as Alpha, but the slow rate of delivery (initially two per month) and the extensive modifications that had to be carried out by the dockyards meant that only eighteen ships were reequipped before the Armistice.

At the same time, first 50 and then 150 of the latest Thornycroft DCTs were ordered for installation on auxiliaries and the older flotilla craft. The fleet torpedo boats of the Bourrasque and L’Adroit classes were each to have received two of these DCTs and their associated ready-use racks in place of the after gun mounting. However, as with Asdic, not all of the orders were fulfilled and few ships were modified prior to June 1940.

4. Submarine

The French showed an early commitment to the submersible torpedo boat, which they considered ideally suited to harbor defense and for use against surface ships in confined waters. However, from the plethora of experimental designs, not a single successful production boat emerged, and in the aftermath of the First World War, the Comission d’Etudes Pratiques des Sous-Marins (CEPSM) conducted a thorough evaluation of existing types and future requirements, which included a study of the German U-boats that had made such a profound impression in 1917–1918. The first fruits of this study were a large oceangoing patrol submarine modeled on the German Ms Type and a 600-tonne coastal defense submarine based on the German UB-III. The 600-tonne type spawned successors of the 630-tonne and Amirauté types, all of which were funded under the défense des côtes budget, and a series of small minelayers. The patrol submarines of the Requin class would be succeeded by a fast fleet submarine, the 1,500-tonne type, intended to scout for the battle fleet and to attack enemy warships. The two lead boats had a maximum speed on the surface of only seventeen knots, but in later units this was increased to nineteen to twenty knots.

The coastal submarines were grouped in divisions of four, and the divisions distributed among the four major Régions Maritimes, including North Africa. They were to be deployed in adjacent, non-overlapping patrol areas off the ports and harbors of those regions outside the protective minefields and antisubmarine nets. In this role they constituted the outer layer of a fixed static defense. Their minelaying counterparts were intended for offensive minelaying in the Mediterranean’s shallow waters.

The fleet submarines of the 1,500-tonne type, which were likewise grouped in divisions of four, were intended to operate in support of the seagoing surface forces, scouting for them and searching for the opportunity to make attacks on the enemy fleet. As the British and the Americans had found with their own attempts at a fleet submarine, communications between the submarines and friendly surface units were problematic, and station keeping for submarines running on the surface in close proximity to the fleet was potentially hazardous. While seventeen to twenty knots was in theory adequate for maneuvering close to a battle fleet with a cruising speed of only fourteen or fifteen knots, the advent of the fast battleship during the 1930s made such combined operations unlikely. The 1,500-tonne boats were therefore used as conventional patrol submarines during the Second World War.

The French subscribed to the League of Nations protocol restricting the employment of submarines against merchant shipping, and the single French cruiser submarine, the 3,300-ton Surcouf, was designed to conform with international law; she had additional accommodation for forty prisoners.

5. Amphibious Operations

The French had a colonial empire that covered the globe and had an extensive network of overseas bases. It was envisaged that local colonial forces would be reinforced in an emergency by troops carried by liners requisitioned for the purpose, or by warships. The Marine Nationale operated a number of “colonial sloops,” heavily armed to give fire support to the troops ashore and with accommodation for a large detachment of fusiliers marins, equivalent to the Royal Navy’s marines, which would be used to stiffen the resistance of the colonial troops to any hostile attack.

Amphibious operations were undeveloped. Trials of prototype landing craft took place at Lorient in 1935/1936, but no program of construction ensued. Troops were generally disembarked at pierheads and jetties, or sent ashore in boats. The only attempted opposed landing was at Dakar by the Free French forces, and the troops were embarked either in sloops (fusiliers marins) or in converted troopships (regular army). The landing failed due to lack of suitable equipment and doctrine.

6. Trade Protection

In the buildup to war in 1939 it was agreed with the Royal Navy that the Marine Nationale would have primary responsibility for the English Channel, the waters between West Africa and the Cape Verde Islands, and the western Mediterranean. Cargo vessels and troopships generally sailed in convoys of half a dozen ships, with a close escort of older destroyers, torpedo boats, or sloops. All of these types were found to lack the endurance necessary for escort work, particularly if evasive measures such as zigzagging were employed, and the light torpedo boats, which had been designed for coastal defense, had poor antisubmarine warfare (ASW) capabilities.

Had Italy entered the conflict earlier, the convoys in the western Mediterranean would have been supported by fast groupings of cruisers and contre-torpilleurs, which would have intervened if the convoys were attacked by the fast light forces of the enemy.

7. Communications

In wartime, ships at sea were expected to maintain radio silence where possible to minimize the possibility of disclosing their position to the enemy. Divisions were maneuvered using the traditional technique of hoisting signal flags, and instructions were transmitted within visual range using signal projectors. Embarked aircraft radioed sighting information to the launch ship, whereas shore-based reconnaissance planes reported to a headquarters ashore, which maintained an overall tactical plot and retransmitted relevant data to the sea-based commander’s flagship.

In the event of the breakdown of fire control aboard one ship of a division, range data could be transmitted from the other ships via concentration dials as in the Royal Navy. These were removed from 1940 as VHF (very high frequency) short-range radio became more widely available.

A. SHIPS

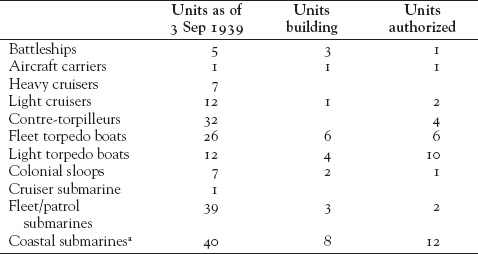

In 1939 all that remained of the fleet that served in the Great War were the three “super-dreadnoughts” of the Bretagne class, which had been partially modernized and were still regarded as first-line units, and the two older battleships of the Courbet class, now used only for training. From 1922 onward, under the driving force of Navy minister Georges Leygues, a completely new fleet of modern surface ships and submarines had been constructed that, on paper at least, could rival any in Europe. The major units are outlined in table 1.2.

TABLE 1.2 Major Units on 3 September 1939

a Includes minelaying submarines.

The Bretagne class had been extensively modernized during the 1920s and early 1930s: the elevation of their main guns had been increased and director control provided for the main and secondary batteries; they also received high-angle (HA) guns to provide antiair (AA) capability, and their coal-fired boilers were replaced by modern oil-fired units. However, there was a limit to what could be done with such a dated design; by 1939 standards, the Bretagne class was slow and had inadequate horizontal protection against plunging shells.

The recently completed Dunkerque and Strasbourg were very different ships. Inspired by the early British interwar designs, they mounted their eight 330-mm guns in two quadruple turrets forward, and their “all-or-nothing” protection scheme featured a relatively short citadel protected by heavy armor: there were an armored belt 225-mm thick (increased to 280-mm in Strasbourg) and a 115–125-mm main armored deck backed up by a 40-mm “splinter deck” beneath. Designed to hunt down the German Panzerschiffe, they were as fast as the British battle cruisers, with a top speed of 29.5 knots. However, their dual-purpose secondary battery of 130-mm (5.1-inch) guns in quadruple and twin mountings was not a success; training and elevation speeds were too slow to be effective against modern aircraft, and the 130-mm shell was too light to stop a destroyer.

The new 35,000-ton battleships of the Richelieu class were enlarged Dunkerques, with 380-mm guns and heavier armor. They were initially to have had a dual-purpose secondary battery of fifteen 152-mm (6-inch) guns in triple turrets, but while the first ship was fitting out it was decided to substitute twelve 100-mm HA guns in twin mountings for the two amidships 152-mm turrets. Maximum speed was thirty-two knots, making them even faster than the latest Italian battleships of the Littorio class. Richelieu was nearing completion when she was compelled to flee to Dakar in June 1940; her sister Jean Bart was still some twelve months away from completion when she too sailed for North Africa, remaining at Casablanca until August 1945. Construction of a third ship, Clemenceau, was abandoned.

The first cruisers built for the Marine Nationale during the interwar period were the three units of the Duguay-Trouin class. They were fast, modern ships of 8,000 tons armed with eight 155-mm guns in twin, power-operated turrets, but they were virtually unprotected. When the Washington Treaty established the upper limit for cruisers at 10,000 tons with 8-inch guns, the French opted initially for an enlarged Duguay-Trouin armed with eight 8-inch guns in twin turrets. Like their predecessors, the two ships of the Duquesne class were fast (thirty-four knots designed) but virtually unarmored, relying for their survival on tight compartmentalization with only light splinter protection for their magazines and turrets. They were followed by a series of four “treaty” cruisers of the Suffren type, each of which had improved protection at the expense of two knots in speed. The last of France’s treaty cruisers, Algérie, was of a radically different design and was much more heavily protected, with a 110-mm armored belt and an 80-mm armored deck. She also carried a much more powerful dual-purpose secondary battery of twelve 100-mm guns in twin mountings.

Although France failed to ratify the London Treaty of 1930, the next class of cruisers closely followed its provisions. The six ships of the 7,600-ton La Galissonnière class were armed with nine 152-mm guns in triple turrets, and protection was almost on a par with Algérie. They proved very successful and were to have been followed by three improved ships of the De Grasse class, only the first of which had been laid down by the outbreak of war. The French also completed two minelaying cruisers during the early 1930s: the Pluton and the Émile Bertin, and a purpose-built training cruiser, the Jeanne d’Arc.

The surface warship type with which the Marine Nationale came to be most closely associated during the interwar period was the contre-torpilleur. In essence, the contre-torpilleurs were large, powerfully armed but lightly built superdestroyers. Operating in homogeneous three-ship divisions, their missions were to screen and scout for the battle fleet, to protect France’s sea lines of communication in the western Mediterranean, and to attack those of Italy in the central Mediterranean. The first six ships of the Jaguar class were armed with five 130-mm guns in single open mountings and six 550-mm (21.7-inch) torpedo tubes in two triple centerline mountings; in later units the 130-mm was replaced by progressively improved models of the heavier 138.6-mm (5.45-inch) gun, and the number of torpedo tubes was increased to nine. The contre-torpilleurs were characterized by their high speed: the Jaguars were designed for 35.5 knots, the Le Fantasques for thirty-seven knots. These speeds were much exceeded on trials, with Le Terrible attaining almost forty-three knots; even in fully loaded wartime condition, a three-ship division could comfortably maintain thirty-four knots in favorable sea conditions.

Thirty contre-torpilleurs of the above types were completed between 1927 and 1936. The last of the contre-torpilleurs, the Mogador and Volta, were designed to operate with Dunkerque and Strasbourg in the broader swells of the Atlantic. Although they were larger than their predecessors and more robustly built, their twin power-operated 138-mm mountings never worked properly despite repeated modifications to their reloading systems. Four slightly modified ships of the class had been authorized 1938–1939 but were cancelled before work could begin.

The third type of surface ship in the 1922 program was a destroyer (torpilleur d’escadre—literally, “fleet torpedo boat”) intended to accompany the battle fleet. Influenced by the British Modified “W” class of 1918, the design featured the heaviest guns of any contemporary destroyer. In fact, the armament was only one gun short of that of the contemporary contre-torpilleurs of the Jaguar class. Twelve ships of the Bourrasque class were followed by fourteen of the L’Adroit class. Most failed to make their modest designed speed of thirty-three knots, endurance was poor, and they suffered from topweight problems. At the beginning of the Second World War, they disembarked two of their six torpedoes and lost the no. 4 gun as compensation for additional depth charge throwers.

When the Marine Nationale embarked on the construction of fast battleships, it became clear that the fleet torpedo boats designed during the 1920s were too slow to accompany them, and a new high-speed design modeled on the latest contre-torpilleurs was adopted. The Le Hardi class were armed with six 130-mm guns in twin mountings and seven 550-mm torpedo tubes; they had a designed speed of thirty-seven knots, which was exceeded on trials. Eleven ships had been laid down by the outbreak of war, and an additional five authorized. Only the lead ship had run trials by the time of the Armistice, but six others were rushed to completion and entered service during 1940–1941.

In September 1939 the French submarine fleet was one of the largest in the world and was considered by many in the Marine Nationale to be its most powerful and influential arm. Nine oceangoing boats of the Requin class were followed by thirty fleet submarines of the 1,500-tonne type, with progressive technical improvements to each subgroup; the last six units (Agosta subgroup) were capable of twenty knots on the surface. The twelve coastal submarines of the 600-tonne type were followed by sixteen boats of an improved 630-tonne type, then by six boats built to a standardized Service Technique des Constructions Navales (STCN) design.2 In parallel with the coastal boats, a class of six coastal minelayers (Saphir class), armed with thirty-two Hautter-Sarlé HS4 mines in vertical external tubes, was built at the rate of one per year. All of these designs featured trainable twin, triple, and even quadruple external torpedo tubes, which made possible large torpedo salvos and considerable flexibility in firing angles; most carried a mix of the powerful, long-range 550-mm torpedo and a smaller 400-mm torpedo for use against escorts and targets of opportunity.

The submarine cruiser Surcouf was authorized under the 1926 program and was to have been the first of six units intended for the protection of French sea communications in distant waters and for commerce raiding. Armed with 203-mm (8-inch) guns in a rotating twin turret and equipped with a light reconnaissance aircraft carried in a watertight hangar, Surcouf was one of the technological wonders of her age; in service, she proved conceptually defective and technically unreliable.

The new generation of French submarines authorized from 1934 comprised two types: a large 1,800-ton fleet boat with a surface speed of twenty-two knots (Roland-Morillot class), and an enlarged coastal type capable of seagoing patrol (Aurore class). There was also to be a coastal minelayer of an improved Saphir type. None of these submarines was commissioned before the outbreak of war, and only Aurore was completed before the Armistice of June 1940.

In September 1939 the main surface forces of the Marine Nationale were organized as follows:

1. Ship-based

The Marine Nationale’s solitary carrier, Béarn, was of limited military value in 1939; she was considered too vulnerable to operate against modern Italian land-based aircraft in the Mediterranean and too slow to operate with the Force de Raid in the North Atlantic. Her air groups were disembarked the day after war broke out, and during early 1940 she was used first to train Navy pilots in the Mediterranean and then as a transport for gold and aircraft between France and Canada. Her two nine-plane fighter squadrons (AC1/2) were still equipped with the obsolescent Dewoitine 376 high-wing monoplane and were assigned to shore bases at Calais and Hyères.3 The two attack squadrons (AB1/2) were being reequipped with American Vought 156F and Loire-Nieuport 401 dive bombers, respectively, and following landing trials in early 1940 these too were based ashore ready for the completion of the new carrier Joffre, the construction of which was abandoned in June 1940.

Shortly before the outbreak of war, the air group of the aviation transport Commandant Teste was embarked and she was dispatched to Oran as part of the newly formed 6e Escadre, which was tasked with cooperating with the British at Gibraltar in the western Mediterranean. However, of her two embarked squadrons, HB1, with the new and impressive Laté 298 float torpedo-bomber, would be based on Arzew, and the surveillance squadron HS1, with six Loire 130s, followed shortly afterward.

2. Shore-based

In 1936 the Marine Nationale regained control of its shore-based naval aircraft from the Air Ministry. The shore-based aéronavale squadrons were predominantly of two types: long-range maritime patrol (designation “E”) and surveillance (“S”). There were also two squadrons of torpedo-bomber seaplanes (“B”) at Berre in the south of France.

The land-based squadrons generally comprised six aircraft and were distributed among the five maritime regions, this attribution being part of the squadron designation for surveillance aircraft (1S2 = the second surveillance squadron of the 1st Maritime Region). The standard allocation was a single patrol squadron and two squadrons of surveillance aircraft to each region. The 4th Maritime Region, which covered the whole of French North Africa, had three patrol squadrons, and the 3rd Maritime Region, which was responsible for the narrow waters between France and Italy in the western Mediterranean, had six surveillance squadrons, one of which was based in Corsica. There were also small detachments of patrol/surveillance aircraft in French West Africa, the West Indies, and the Pacific islands.

During the late 1930s the Marine Nationale invested heavily in surveillance and patrol aircraft. Some 125 of the excellent Loire 130 seaplanes were built, and as these were made available to battleships and cruisers, the older but equally useful GL 812 models were transferred to the shore-based squadrons. Older types such as the CAMS 37 and 55 models were more vulnerable to modern fighters, as were the large seaplanes used for long-range patrol.

C. WEAPON SYSTEMS

1. Gunnery

French heavy guns, which had many component parts, continued to be manufactured using a mix of traditional and modern technology. Upward-opening screw breechblocks were a French innovation. In the lighter guns, the German-pattern sliding breech was adopted from the late 1920s, resulting in a much higher rate of fire than for earlier models. Muzzle velocities in the turret-mounted guns tended to be high for a given shell weight; however, the French were not as ambitious as the Italians in this respect, and most destroyer and AA guns had a relatively low muzzle velocity.4

French gun mountings varied considerably in design. They were usually powered electrically; later installations had remote power control for training and elevation, but the remote power control systems developed were not successful in service, and they were often switched off or even removed. For the new generation of battleships, quadruple turrets were favored for both the main and secondary batteries largely because of the economies they provided in weight of armor and centerline space. Vulnerability to damage was reduced by dividing each quadruple turret into two independent gun houses with a central 40- or 45-mm bulkhead of special steel. Quadruple turrets were less successful in the antiaircraft role, which favored lightweight gun mountings with high training and elevation speeds.

The complexity of the replenishment and loading mechanisms adopted for many of the turret-mounted guns was a major issue in some designs. The Marine Nationale opted for dual-purpose quadruple 130-mm and triple 152-mm guns for the new generation of battleships, but both of these weapons proved difficult to load at high angles of elevation (due in part to underpowered rammers), and there were frequent breakdowns and jams. Even worse were the 138.6-mm twin gun mountings of the Mogadors, the loading mechanisms of which had originally been designed for 130-mm guns firing fixed ammunition. Designed for a firing cycle of ten rounds per gun per minute, they attained only three or four rounds per gun per minute on trials; even after two years of extensive modification, the twin mounting delivered only the same amount of ordnance as the single gun of the Le Fantasque class.

The 90-mm and 100-mm HA guns employed for the secondary batteries of the cruisers were much more successful and proved robust and reliable; they subsequently displaced the two amidships 152-mm dual-purpose mountings on Richelieu and Jean Bart. However, the 37-mm light AA weapons (single Mle 1925 and twin Mle 1933) had too slow a rate of fire to be effective against modern aircraft, and the 13.2-mm Hotchkiss machine gun (in twin and quad mountings) was too lightweight to do serious damage and lacked sufficient range. New, more advanced 37-mm and 25-mm models were under development when war broke out in 1939, but the former never entered production and the latter became widely available only in 1942.

French shell (armor-piercing [AP] only for the big guns, semi-armor-piercing and high explosive for the medium-caliber guns) was generally well designed, and by 1939 shells with dye bags inside the ballistic cap were coming into service, enabling ships operating in divisions of three to identify their shell splashes by color—generally white/yellow, red, and green. A design fault in the base of the early 380-mm AP shells, which were intended to accommodate canisters of toxic gas, resulted in premature detonation of the shell in three of the four guns in turret II of Richelieu at Dakar in September 1940, wrecking the guns. This problem was subsequently resolved by strengthening the base of the shell. Because of a shortage of charges, SD19 propellant intended for Dunkerque and Strasbourg was remanufactured for Richelieu at Dakar, but the only problem resulting from this was a reduction in muzzle velocity beyond what had been anticipated.

A problem experienced with the large- and medium-caliber guns in quadruple turrets was dispersion caused by gun blast interference. This was only really resolved postwar, when delay coils were fitted to the outer guns.

The French battleships and cruisers laid down before 1914 had been designed to fight at relatively short battle ranges. Modern coincidence rangefinders were purchased from the British company Barr & Stroud during the early part of the war, but the fire-control systems necessary for long-range fire were not developed, and in 1918 the Marine Nationale found itself lagging some way behind the Royal Navy in this respect. Bretagne trialed a British Vickers fire-control director from 1920, and this led to the development of a model of French design and manufacture by St. Chamond-Granat. This was subsequently fitted in all of the older battleships and was the basis of the systems that equipped the battleships of the new generation.

French industry also made considerable progress in the development of optical rangefinders during the 1920s. SOM (Société d’Optique et de Méchanique de Haute Précision) produced coincidence rangefinders with three- or four-meter bases for the new generation of flotilla craft, and by the mid-1930s OPL (Optique de Précision Levallois-Perret) had developed an extensive range of stereoscopic rangefinders. The new battleships had 12-m (14-m in the Richelieu class) and 8-m OPL rangefinders for their main armament and 6-m and 5-m OPL rangefinders (8-m and 6-m in the Richelieu class) for their secondary guns. The latest contre-torpilleurs of the Le Fantasque and Mogador classes had 5-m and 4-m models.

The French were aware of British developments in radar through their close contacts 1939–1940, but it was the spring of 1942 before surveillance radars of indigenous design and manufacture (détecteur électro-magnétique, or DEM) were installed in major units. In Strasbourg, which received the prototype model, four small rectangular antennae were fitted atop the main yards projecting at 45 degrees from the tower; the starboard forward and port after antennae were for transmission, the opposite pair for reception. Trials were cut short by events, but early tests indicated a detection range against aircraft of 50 km with a bearing accuracy of ±1 degree and a range accuracy of ±50 m under favorable conditions.

2. Torpedoes

The standard French torpedo of the Great War was a 450-mm model using wet-heater propulsion; it had a warhead of 144 kg and a range of only 3,000 m at thirty knots. Following the end of the conflict, the French immediately embarked on the design of larger, more powerful 550-mm torpedoes capable of being fired at long range. The Model 1919D, 8.2-m long with a 238/250-kg picric acid warhead, had a range of 6,000 m at thirty-five knots and 14,000 m at twenty-five knots. Its much-improved successor, the Model 1923DT, which had an alcohol-fueled four-cylinder radial engine, was 8.6 m long with a 308-kg TNT warhead, and had a range of 9,000 m at thirty-nine knots and 13,000 m at thirty-five knots. This latter model would be carried by all the French flotilla craft built between the wars.

The standard submarine torpedo between the wars was the 550-mm Mle 1924V, which was developed simultaneously with the Mle 1923DT and had the same propulsion system but at 6.6 m was shorter and optimized for speed rather than long range: the early variants had a range of 3,000 m at forty-four knots, 7,000 m at thirty-five knots; in later variants range was increased. During the late 1920s a smaller torpedo with an advanced propulsion system using alcohol injection, the 400-mm Mle 1926V, entered service. Carried in conjunction with the 550-mm, it was intended for small escorts and targets of opportunity. With a TNT warhead of 144 kg, the 400-mm Mle 1926V had a range of 1,400 m at forty-four knots (in later variants range was increased first to 1,800 m, then to 2,000 m). A Mle 1926W variant was developed for motor torpedo boats, and a Mle 1926DA model for air drop.

3. Antisubmarine Warfare

The standard French depth charge was the Guiraud Mle 1922, which had a 200-kg TNT charge. On the contre-torpilleurs and the fleet torpedo boats depth charges were stowed in rows of six or eight in twin tunnels located beneath the quarterdeck, and discharged via square stern apertures using a continuous chain mechanism driven by electric motors. Depth settings were 30, 50, 75, or 100 m, with 50 m and 100 m being the most commonly used. The heavy depth charges were sometimes complemented in wartime by lightweight 35-kg depth charges carried in racks on the quarterdeck and discharged manually; these were also fitted in cruisers and light patrol craft.

To create a broader depth charge pattern, depth charge throwers (DCT) were used, and although many of these were not installed in peacetime due to topweight problems, they were again embarked in 1939–1940. There were two models: a British Thornycroft 240-mm model dating from 1918, and the lighter French 120-mm Mle 1928. Both launched depth charges with a 100-kg charge, the British model to a distance of 60 m, the Mle 1928 to a distance of 250 m. The Mle 1928 could launch two depth charges per minute, and there was an adjacent rack with a single reload; additional depth charges were stowed in a below-decks magazine aft.

During the late 1920s the Marine Nationale experimented with two models of the Italian Ginocchio towed antisubmarine torpedo: a medium type weighing 62 kg that was towed at a depth of 15–37 m; and a heavier type weighing 75.5 kg with a maximum towing depth of 53 m; both types had a 30-kg warhead. Trials with the torpedoes were unsuccessful and, although revived 1939–1940, the Ginocchio was never fitted operationally.

There was provision for ultrasonic submarine detection apparatus on all the French interwar flotilla craft and cruisers, but although many systems were developed and tested, none was successful. The only homegrown model to enter service was the SS 1, which was fitted to a number of fleet torpedo boats in 1939–1940. It too was a failure, and the Marine Nationale was compelled to purchase the British Asdic 128; in French service it became “Alpha,” but few models were delivered prior to June 1940, and none was fitted by the time of the Armistice.

4. Mines

There were two main types of mine designed to be laid by surface ships: the Hautter-Sarlé H5 and the Bréguet B4; both were traditional moored contact mines. The Hautter-Sarlé H5, which entered service in 1928, had an overall weight of 1,160 kg and a 220-kg TNT charge. The cruiser minelayer Pluton was designed to carry 220 (250 max.) on four upper-deck rails, each 192-m long; the mines were launched over the stern via angled ramps using continuous chains powered by electric motors. The HS4 mine carried by the minelaying submarines of the Saphir class was similar; 32 were stowed externally in 16 vertical tubes located in the outer casing on either side of the conning tower. A project to develop mines launched from the torpedo tubes of submarines was abandoned in 1938.

The Bréguet B4 mine was considerably smaller, being only half the weight with an 80-kg TNT charge. It was designed for the later contre-torpilleurs, which entered service from 1933 and could carry twenty B4 mines on each of their 25-m twin Decauville tracks. The tracks comprised a fixed after section capable of accommodating five mines and removable sections that took some six hours to assemble; in wartime they were stowed in a below-decks magazine. The minelaying cruiser Émile Bertin was fitted with similar tracks 50 m in length, capable of accommodating eighty-four B4 mines. Unlike her predecessor Pluton, Émile Bertin was a cruiser first and a minelayer second, and the weight of the mines had to be compensated for by disembarking her catapult and aircraft.

D. INFRASTRUCTURE

1. Logistics

Oil firing was adopted for destroyers from about 1909, but coal firing was retained for the battleships laid down 1910–1914. After the Great War it became clear that oil was the future; all the ships designed from 1918 had oil-fired boilers, and some coal-fired boilers on the older battleships were replaced. However, this had serious implications for stocks. In 1926 there was sufficient storage ashore for only 100,000 tons of fuel oil and 17,000 tons of diesel fuel. In the same year it was decided that these figures were to be increased to 1,500,000 tons and 140,000 tons, respectively—equivalent to nine months’ consumption. Because of fears of coastal or aerial bombardment, fuel tanks were to be located underground. The period 1926–1929 also saw the laying down of four purpose-built oilers (the navy’s first), each of 8,600-tons, to be used for the importation of oil during peacetime and for replenishment in time of war.

By January 1939 there were reserves of 1,100,000 tons of fuel oil and 90,000 tons of diesel, and an additional 1,745,000 tons of tank capacity (including 105,000 tons for diesel) had been authorized. These figures included substantial stocks overseas to support deployments: at Casablanca (North Africa), Dakar (West Africa), Diego Suarez (Indian Ocean), Saigon (Far East), and Fort de France (West Indies). Ten new tankers were also ordered 1936–1939; only three of these would enter service prior to the Armistice.

2. Bases

The main bases in metropolitan France were at Brest (headquarters of the Atlantic Fleet) and Toulon (Mediterranean Fleet). Both had extensive maintenance facilities, including 250-m graving docks capable of accommodating the largest modern battleships. The other major fleet base was at Bizerte in Tunisia, which could not only accommodate a fleet of ships but also had a well-developed naval dockyard at Ferryville capable of major repairs to all types of ship; the No. 2 Dock was 254 m by 40.6 m. There were important bases and naval dockyards at Cherbourg (North Sea/Channel areas) and at Lorient (Atlantic coast).

With Italy increasingly seen as France’s potential enemy in a Mediterranean conflict, the Marine Nationale feared that both Toulon and Bizerte would be vulnerable to air attack and in 1934 decided to undertake the construction of a new naval base capable of accommodating the Mediterranean Fleet at Mers el-Kebir, west of Oran (Algeria). Work began in 1936: there was to be a major anchorage sheltered by a 2,000-m jetty, new coast defense guns for the existing forts, underground command bunkers, batteries of medium and light AA guns, piers, quays and dry docks, fuel tanks, and munitions stocks. However, little of this was in place by July 1940, when major elements of the French Atlantic Fleet were attacked by the British; only a 900-m stretch of the main jetty had been completed, and communications with Oran were rudimentary.

The French overseas bases, especially those in North and West Africa, were strategically important but had limited facilities for maintenance. This would become a serious problem after June 1940 when major units of the Atlantic Fleet took refuge there. Dakar had only a small graving dock, and Casablanca had a floating dock capable of accommodating only flotilla craft and submarines.

An important element in the défense des côtes strategy was the provision of batteries of large- and medium-caliber coast defense guns, generally sited on headlands commanding the harbor approaches, for all major fleet bases and anchorages. During the Great War, many of the original guns were dismantled and repatriated to bolster the Western Front, but during the 1920s and 1930s, considerable sums were spent on rebuilding the fortifications and providing them with guns removed from the prewar battleships and cruisers. Each of the major batteries, generally comprising between two and four guns, was provided with a battery command post equipped with a 5-m armored rangefinder and a fire control computer, a Bréguet 150-cm searchlight projector for night firing, and in some cases an acoustic aircraft detection system called a mur d’écoute (sound mirror). Of particular note were the powerful batteries at Cape Cépet (Toulon) and at Bizerte comprising 340-mm guns from the uncompleted battleships of the Normandie class in twin armored turrets, the 240-mm guns in twin armored turrets at Dakar, and the 240-mm and 194-mm batteries in open mountings at Mers el-Kebir/Oran and Casablanca. Passes and harbor entrances were defended by batteries of 100-mm and 75-mm guns.

3. Industry

France’s industrial infrastructure suffered badly in the First World War, and considerable rebuilding was necessary before it was again in a position to furnish the navy with the steel, propulsion machinery, and other equipment it required. The ambitious naval programs of the 1920s had the effect of reviving the dockyards and private industry, but they also stretched them beyond their capacity, and by the late 1920s the backlog of construction due largely to the late delivery of components led to a one-year postponement of orders for the ships in the 1928 estimates. Ships were often completed without key items of equipment such as fire-control directors. Industrial problems and social unrest in the mid-1930s resulted in further delays, and the fleet submarines authorized in 1930 took eight years to complete.

The naval dockyards had the key role in the design and construction of surface warships and submarines. Brest laid down the lead unit of virtually every class of interwar cruiser, completing six out of the seven 10,000-ton treaty cruisers and two of the three Duguay-Trouins. Brest also built both the lead ships of the Dunkerque and Richelieu classes, despite not having a building dock sufficiently large to accommodate the full length of the hulls (Dunkerque was “launched” minus her bow, Richelieu minus her bow and stern). Lorient, with its revolutionary undercover building hall, the Forme Lanester (completed 1922), also built cruisers and was the lead yard for the contre-torpilleurs; Cherbourg was the lead yard for the larger submarines. Follow-on units were generally ordered from the private shipyards. Strasbourg and Jean Bart were built by Penhoët–A. C. Loire at Saint Nazaire, the latter in a purpose-built facility with parallel building and fitting-out docks allowing the completed hull to be floated sideways from one to the other. Light cruisers and destroyers were built at private shipyards such as A. C. Loire, A. C. Bretagne, A. C. de France, F. C. de la Gironde, and F. C. de la Méditerranée at La Seyne (opposite the naval dockyard at Toulon).

The orders for the early coastal submarines of the 600-tonne and 630-tonne types were placed in batches with traditional private submarine builders such as Augustin-Normand, Schneider, and Dubigeon, who produced competing designs to broad STCN requirements. There were some benefits from competitive design, but the lack of standardization of equipment and spares proved to be a major operational drawback, and later coastal submarines were built by the same companies to a standard STCN design.

Major items of equipment such as guns, machinery, and torpedoes were designed and tested in-house. Indret (near Nantes) was responsible for the development of boilers and turbine machinery, Guérigny for the manufacture of anchors, chains, and special steels; Saint-Tropez for the manufacture of torpedoes; and Ruelle for the design and manufacture of guns, shells, and charges. Gun mountings and fire-control systems, conversely, were often designed by private industry. Saint-Chamond was prominent in the design of the large quadruple mountings for the new generation of battleships, and of fully enclosed gun mountings for smaller ships; Saint-Chamond also combined with Granat, who supplied the transmitting systems for the guns in all warships, to produce the first director systems of French design. SOM and OPL produced the new generation of coincidence and stereoscopic rangefinders.

IV. RECAPITULATION

A. WARTIME EVOLUTION

The main problem that the Marine Nationale faced in September 1939 was that the war that broke out in Europe did not follow the course that had been anticipated. This was also a problem faced by other major navies such as that of Britain and the United States. However, British and U.S. maritime forces had been developed primarily for long-range operations and were therefore more inherently flexible in terms of the theaters in which they could be effectively employed. In contrast, the Marine Nationale, which did not subscribe to Mahanian “sea control” doctrine, had prepared for two distinct types of naval warfare in two very different maritime theaters: on the one hand, security operations in the open waters of the North Atlantic, where the primary threat was posed by German commerce raiders, and on the other, fleet-on-fleet action against Italy in the narrow waters of the Mediterranean.

Operations against the German commerce raiders proceeded broadly according to plan. The Force de Raid was divided into two: Dunkerque, the light cruisers, and half of the contre-torpilleurs operated in the North Atlantic, often alongside ships of the Royal Navy, to block incursions via the Denmark Strait by the German Panzerschiffe and the fast battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau; Strasbourg and the remaining contre-torpilleurs were deployed to Dakar, where they operated in conjunction with the British carrier Hermes as Force X to hunt German surface raiders in the South Atlantic.

However, Italy failed to enter the war as expected; as a result, the French Mediterranean Fleet and its ships never had the opportunity to show off their undoubted capabilities in the maritime environment for which they had been designed. The modern heavy cruisers based at Toulon were rotated in pairs through Force X (subsequently Force Y) at Dakar, taking some of the Mediterranean Fleet contre-torpilleurs with them. Other units were deployed to ports in northern Britain for the Norway operation of April 1940. However, the bulk of the fleet was retained in Mediterranean waters to cover the anticipated Italian declaration of war. When this finally happened on 10 June 1940, it came too late for the Marine Nationale to affect the overall military situation. Heavy cruisers and contre-torpilleurs raided Genoa and Vado on the night of 13–14 June, but this was the only operation of note against the Italians before the Armistice was signed on 22 June.

June and July were difficult months for the Marine Nationale. Under the terms of the Armistice (Article 8), the entire fleet was to be demobilized and disarmed in French metropolitan ports under German and Italian supervision. Following negotiations, the Germans and Italians made concessions: the French would be permitted to demobilize a substantial part of the fleet in North African ports, the remaining units returning to unoccupied Toulon; no ships would be required to return to ports in occupied France. Demobilization was already proceeding, reservists were preparing to disembark, coast defense guns were being dismantled, and submarine torpedo warheads deactivated when the Marine Nationale had to face a threat from an unexpected quarter: the Royal Navy. Prime Minister Winston Churchill was unwilling to accept Admiral Darlan’s assurances that no French ship would be handed over intact to the Germans. French warships that had taken refuge in the United Kingdom were to be seized by force, and aggressive action was to be taken against those units of the French fleet outside metropolitan France, with the modern battleships the primary targets.

The powerful squadron under Vice Admiral René Godfroy at Alexandria was subsequently immobilized under the guns of the British Mediterranean Fleet. On 3 July the French Atlantic Fleet at Mers el-Kebir, which included Dunkerque, Strasbourg, and two of the older battleships, was given the ultimatum of sailing with the British Force H or being sunk. After prolonged and somewhat fraught negotiations—which were not helped by the precarious state of communications between the commander in chief on the spot, Vice Admiral Marcel Gensoul, and the French high command—the three battleships of the British squadron opened fire, sinking the older battleship Bretagne and disabling Dunkerque and Provence within ten minutes; Strasbourg and five of the six contre-torpilleurs escaped to Toulon. Four days later Richelieu was disabled at Dakar by a torpedo dropped by a Swordfish aircraft from HMS Hermes.

These unprovoked aggressions by the British gave Darlan a lever to use against the draconian provisions of the Armistice. The French persuaded the Germans and Italians of the wisdom of mobilizing a substantial proportion of the major warships in Toulon to defend Southern France and the African colonies against the threat of attack from their former Allies. In September a grouping of modern warships comprising three light cruisers and three contre-torpilleurs designated Force Y was dispatched to West Africa to counter Gaullist influence. These ships served to bolster the local forces at Dakar when in late September General Charles de Gaulle, accompanied by a powerful British squadron, attempted unsuccessfully to rally Senegal to the Free French cause.

From late 1940 until November 1942 the active part of the fleet at Toulon, now designated the Forces de Haute Mer (FHM) under the command of Admiral Jean de Laborde, comprised the flagship Strasbourg, three heavy and two light cruisers, and six or more contre-torpilleurs. Two training sorties were permitted every month, and the Marine Nationale took the opportunity of rotating the modern cruisers and contre-torpilleurs between full commission and refit/maintenance (gardiennage d’Armistice). Despite the German occupation of northern France, where most of the French defense industry was located, light AA guns including the twin 37-mm Mle 1933, the single Hotchkiss 25-mm Mle 1939 G, and the Browning 13.2-mm MG were now becoming available in larger numbers, and the opportunity was taken to upgrade ships during refit. The British Asdic sets delivered before the Armistice were also finally installed, and from the spring of 1942 radar (DEM) of French design and manufacture was fitted to some of the major units.

The situation for the ships stationed in North and West Africa was less favorable. Refit and maintenance facilities were poor, and equipment upgrades were limited to the mounting of additional light AA weapons transported by freighter from metropolitan France. Fuel and munitions stocks had to be conserved for use in the event of an Allied aggression, so training at sea was minimal and was confined to local waters.