If your Documents folder contains nothing but laundry lists and letters to your mom, data security is probably not a major concern for you. But if there’s some stuff on your hard drive that you’d rather keep private, Windows can help you out. The Encrypting File System (EFS) is an NTFS feature, available in Windows 8.1 Pro and Enterprise, that stores your data in a coded format that only you can read.

The beauty of EFS is that it’s effortless and invisible to you, the authorized owner. Windows automatically encrypts your files before storing them on the drive, and decrypts them again when you want to read or modify them. Anyone else who logs onto your computer, however, will find these files locked and off-limits.

If you’ve read ahead to Chapter 24, of course, you might be frowning in confusion at this point. Isn’t keeping private files private the whole point of Windows’s accounts feature? Don’t Windows’s NTFS permissions (The Default User Profile) keep busybodies out already?

Yes, but encryption provides additional security. If, for example, you’re a top-level agent assigned to protect your government’s most closely guarded egg salad recipe, you can use NTFS permissions to deny all other users access to the file containing the information. Nobody but you can open the file.

However, a determined intruder from a foreign nation could conceivably boot the computer using another operating system—one that doesn’t recognize the NTFS permissions—and access the hard drive using a special program that reads the raw data stored there. If, however, you had encrypted the file using EFS, that raw data would appear as gibberish, foiling your crafty nemesis.

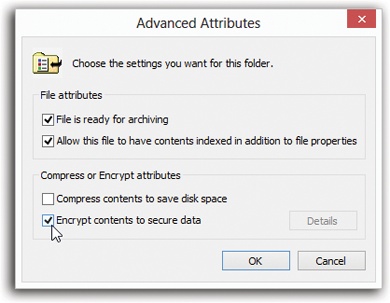

You use EFS to encrypt your folders and files in much the same way that you use NTFS compression. To encrypt a file or a folder, open its Properties dialog box, click the Advanced button, turn on the “Encrypt contents to secure data” checkbox, and then click OK (see Figure 23-4). (To build a quicker way, see Dynamic Disks.)

Figure 23-4. To encrypt a file or folder using EFS, turn on the “Encrypt contents to secure data” checkbox (at the bottom of its Properties dialog box). If you’ve selected a folder, a Confirm Attribute Changes dialog box appears, asking if you want to encrypt just that folder or everything inside it, too.

Depending on how much data you’ve selected, it may take some time for the encryption process to complete. Once the folders and files are encrypted, they appear in a different color from your compressed files (unless you’ve turned off the “Show encrypted or compressed NTFS files in color” option; see View Tab).

Note

You can’t encrypt certain files and folders, such as system files, or any files in the system root folder (usually the Windows folder). You can’t encrypt files and folders on Fat 32 drives, either.

Finally, note that you can’t both encrypt and compress the same file or folder. If you attempt to encrypt a compressed file or folder, Windows needs to decompress it first. You can, however, encrypt files that have been compressed using another technology, such as Zip files or compressed image files.

After your files have been encrypted, you may be surprised to see that, other than their color change, nothing seems to have changed. You can open them the same way you always did, change them, and save them as usual. Windows is just doing its job: protecting these files with the minimum inconvenience to you.

Still, if you’re having difficulty believing that your files are now protected by an invisible force field, try logging off and back on again with a different user name and password. When you try to open an encrypted file now, a message cheerfully informs you that you don’t have the proper permissions to access the file.

Any files or folders you move into an EFS-encrypted folder get encrypted, too. But dragging a file out of one doesn’t unprotect it; it remains encrypted as long as it’s on an NTFS drive. A protected file loses its encryption only in these circumstances:

You manually decrypt the file (by turning off the corresponding checkbox in its Properties dialog box).

You move it to a Fat 32 or exFAT drive.

You transmit it via a network or email. When you attach the file to an email or send it across the network, Windows decrypts the file before sending it on its way.

By the way, EFS doesn’t protect files from being deleted. Even if passing evildoers can’t open your private file, they can still delete it—unless you’ve protected it using Windows’ permissions feature (Chapter 24). Here, again, truly protecting important material involves using several security mechanisms in combination.