Pomelos for sale by a Miao villager near Congjiang, in southeastern Guizhou.

Most cookbooks have a chapter “Desserts,” but at some point midway through this project, we looked at each other and agreed that “Desserts” wouldn’t do as a title for this chapter. It’s not that sweet foods don’t exist beyond the Great Wall, because they do, but not as a separate category of prepared foods.

Fresh fruits—melons, pomegranates, mulberries, and other tender fruits of the Xinjiang oases; apples; and the subtropical fruits of Yunnan—are treasured as sweet treats. Kazakhs and Tibetans enjoy sugar added to yogurt. And dried fruits are available almost everywhere. But dessert as we know it in Western countries is a relatively foreign concept beyond the Great Wall.

When we first started traveling here in the 1980s, we would go to great lengths to find tins of peaches, or we’d stand in long queues to buy apples. It wasn’t necessarily that we were craving something sweet, it had more to do with the scarcity of fruit in general. In Tibet in the mid-1980s, we discovered packaged Chinese army rations (see “761s, 1985 to 2006,” page 331), shortbread-like bars that were semisweet and filling, and great with tea and coffee.

A lot has changed since then, of course. Restaurant culture has blossomed, and there are now many open-air markets and street-food vendors, but desserts (or at least what we can find as travelers) remain few and far between: sweet sticky rice with fruit, cookies of various kinds, and deep-fried doughnuts are about it.

When it comes to “indulgences,” tea, beer, and liquor (and, for many people, tobacco) have always been available and much loved. Tea is a way of life beyond the Great Wall and is also a cultural marker: different peoples drink their tea in distinctively different ways (see “Tea, Tea, and More Tea,” page 324). Beer is also common. We don’t know its history, or how it first arrived in China, but bottles of beer, and bowls of beer, can be found almost everywhere. We like the beer, generally. It tastes like real beer, not having been “lightened up” or “calorie-reduced.”

A cup of tea or a glass of beer, some rice pudding or deep-fried sesame balls: welcome to “dessert” beyond the Great Wall.

Rock sugar.

Sesame finds its way into many savory dishes, often in the form of roasted sesame oil, or as sesame paste (see Noodles with Sesame Sauce, page 149), but it is also an important flavoring for sweets. Here, in a Chinese classic that we’ve also seen in bakeries beyond the Great Wall, balls of dough puff up in hot oil as they deep-fry, and the sesame seeds that coat them cook to an aromatic golden brown in the hot oil.

These treats are a delight to the tongue—they’re about texture as well as flavor. All they require from you is a little patience while you get familiar with the frying technique. Read through the instructions carefully before you start cooking, then enjoy. The balls have a slightly crisp exterior, which collapses as you bite in to a tender interior partly filled with sweetened red bean paste.

1 cup glutinous rice flour

⅓ cup sugar

⅓ cup boiling water

About ½ cup Sweet Red Bean Paste (recipe follows) or store-bought red bean paste

Scant ½ cup sesame seeds

Peanut oil for deep-frying (2 to 4 cups)

Mix the flour and sugar together in a bowl. Pour the boiling water over and stir to mix and form a dough. Let stand until cool enough to handle.

Place the filling by your work surface. Divide the dough into 18 pieces (cut in half and then into thirds, and into thirds again). Flatten one piece of dough to a 2-inch round. Place 1 teaspoon filling in the center, pleat the dough up around the filling, and pinch to seal. Roll between your palms to make a rounded ball, then set aside on a lightly floured surface. Fill and shape the remaining balls.

Place the sesame seeds on a plate. Spritz the shaped balls with water. One by one, roll in the sesame seeds to coat and then place them on a tray. Cover the balls loosely with plastic wrap.

Place a large wok, or a deep heavy pot on the stovetop; make sure the wok or pot is stable. (Or use a deep-fryer.) Pour 2 inches of oil into the wok or pot and heat over medium-high heat. Set out a slotted spoon or a mesh skimmer and a paper-towel-lined tray near your stovetop. To test the temperature of the oil, hold a wooden chopstick vertically in the oil, touching the bottom of the pan. If the oil bubbles up around it, it is at temperature. If it starts to smoke, the oil is too hot; lower the heat slightly and test it again. (A deep-fry thermometer should register 250° to 270°F.)

Start by frying just one ball, to get used to the technique. Later on, you can cook 3 or more at a time, depending on the size of your wok or pot. Slide the ball into the oil and cook, using your spoon or skimmer to move the ball around so it colors evenly, for 2 minutes, or until golden. (If it is golden in under 1½ minutes, your oil is too hot; reduce the heat slightly.) Then use the back of your slotted spoon or skimmer to push the ball down firmly, smushing it slightly. It will puff up and then pop back to the surface and turn over; if it doesn’t turn over, turn it over with the spoon or skimmer. After another 30 seconds or so, press down again firmly and turn over; repeat several times more, until the ball is puffed and richly golden, a total of about 5 minutes cooking time, then remove to the paper-towel-lined tray. Do not be impatient! If the ball browns too fast (in less than 1½ minutes), it won’t expand/puff up, and if there are dark brown spots on it (if you don’t keep it moving in the initial 2 minutes), they will prevent it from puffing fully. Cook the remaining balls in batches in the same way, allowing about 5½ minutes cooking time per batch.

Serve hot or at room temperature. The sesame balls are of course best fresh from the deep-fryer, but they are surprisingly good even 12 hours after cooking.

Makes 18 filled sesame balls

Bean paste is used as a filling in many Chinese and Japanese sweets. Use it to fill the Sesame Balls, above, or as a sweet filling for flatbreads.

You can buy red bean paste in Asian grocery stores, but it’s very easy to make your own. The cooked pureed beans are sweetened with sugar and blended with a little lard or oil, so the paste has a silky-smooth texture.

1 cup azuki beans (see Glossary)

¾ cup sugar

¼ teaspoon salt

2 to 3 tablespoons lard, melted, or peanut oil

Soak the beans overnight in water to cover by several inches.

Drain the beans and place in a heavy pot with enough water to cover by 1 inch. Bring to a boil, then reduce the heat and simmer, partially covered, until the beans are soft, about 30 minutes.

Transfer the beans and cooking liquid to a food processor and process until smooth. For a very smooth paste, press through a coarse sieve. Place back in the pot and cook over medium heat, stirring frequently with a long-handled spoon to prevent sticking, for 20 minutes. (The mixture will be thick and may “burp” steam; be careful not to get spattered.)

Stir in the sugar and salt and cook for another 5 to 10 minutes. Remove from the heat and stir in the lard or oil, beating to incorporate it completely. Let cool to room temperature. The filling can be stored in a sealed container in the refrigerator for up to 1 week or in the freezer for up to 3 months.

Makes about 2 cups

These days in Lhasa, more and more people are drinking sweet tea (cha la-mo in Tibetan). It’s a style of tea like that in northern India and in Nepal, made with black tea and only medium strong, sweetened with a little sugar, and made pale with milk. With more open borders, enabling slightly easier travel between Tibet and Nepal and India, it seems to have become very popular, especially among the young people.

Tibetan sweet tea is drunk on its own at any hour, stored in thermoses that keep it hot and that can be brought out whenever a guest arrives. The heat and sweetness are very welcome in the cold, dry air. This recipe is for Lhasa-style sweet tea, shaken just before serving to put a little air into it. If you prefer a stronger brew, increase the amount of loose tea you use, and increase the steeping time too.

2 heaping teaspoons loose tea leaves (Pu’er, Assam, or Darjeeling)

6 cups water

About ½ cup milk, or to taste

About 1 tablespoon rock sugar or regular sugar, or to taste

Place the tea in a teapot or a saucepan with a lid. Bring the water to a vigorous boil in another pan. Pour it over the tea, and let steep, covered, for 5 minutes. Meanwhile, heat the milk until almost at the boil. Remove from the heat.

Pour the tea through a strainer into a large thermos or a well-sealed large container. Add the hot milk and sugar, cover tightly, and shake to blend well. Pour into individual cups.

Serves 4

We’ve come to think that tea-drinking traditions are a good way to describe cultural differences. While we associate central China with clear tea (green or oolong or black), the people living beyond the Great Wall drink tea in many different ways.

In Inner Mongolia, the standard tea is milk tea, often served from a samovar (perhaps because of proximity to Russia, but we don’t know for sure). There even Han Chinese drink milk tea; it’s like a marker of place and belonging. The milk is from local cattle. Mongol nomads and herders add butter and salt to their tea, much as Tibetans do.

In the Xinjiang oases, you’ll see men sitting in open-air tea shops called chai khana (chai is the word for tea), chatting and sipping bowls of clear slightly salty tea, either green tea or black, and again often served from a samovar-like pot (or else from a teapot; see photo, page 176). Up in the Altai Mountains of Xinjiang, Kazakhs and Tuvans drink a lightly salted butter tea. In Guizhou, the Miao and the Dong have a drink known in English as oiled tea. It’s a blend of green tea, puffed rice, soybeans, and peanuts, a small meal in a bowl.

Tea is grown on hillsides in many places in Guizhou province by many different kinds of people, including the Miao and the Dong, but the most famous area for tea beyond the Great Wall is in southern Yunnan. Tea (Camellia sinensis) seems to have originated near here as a wild tree. The slopes of Yunnan’s southern valleys are like a sculpture garden of carefully shaped and tended tea bushes. In early spring, pickers move slowly along the rows of bushes, carefully harvesting young leaves. Later, after the rains of summer, there’s another harvest period. (In their encyclopedic book about tea, The Story of Tea, Mary-Lou and Robert Heiss tell us that in some areas of Yunnan, tea is harvested from tall old trees deep in the jungle.) The traditional variety of tea grown here is the same as that in Assam (in northeastern India), whereas at higher elevations or in the cooler climates of central China’s tea-growing regions, the tea trees are like those of Darjeeling or Fujian.

There’s a long history of tea production in southern Yunnan. Green and black teas are produced, but the Dai and Bulong people are especially famous for another style of tea, known as Pu’er tea (Pu’er is a town south of Kunming). The tea leaves are fermented and pressed into bricks or rounds; the best of these are then aged and command high prices. When brewed, Pu’er tea has a dark color. (It’s known as black tea in China; what we in the West refer to as black tea has a reddish color when brewed and is consequently known as red tea in China.)

A less refined version of fermented tea, made of twigs and stems and coarse leaves, has for centuries been pressed into bricks and transported over the passes to Tibet by horse caravans. A similar tea is shipped to Mongolia. These days the transport is by truck, but coarse-textured dark brick tea is still sold in the markets in Tibet. Butter tea (cha po cha in Tibetan), the classic staple in Tibet, is made of brick tea mixed with hot water, butter, and salt and traditionally churned together. In central Tibet, soda powder (which is like baking soda) is also added to bring out the tea’s color. Butter tea is more like a meal than a drink and is still the staple for many Tibetans. Nomads, rural people, and monks and nuns rely on it to keep them warm and fed. It becomes a very filling meal-in-a-bowl when thickened with tsampa (see “Tsampa in a Storm,” page 179).

A woman picking tea in southern Yunnan in early spring.

A valiant older nun, photographed outside the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa, where she goes every day to pray; the top of her handheld prayer wheel is on the left.

At every hour of the day and night there are people—lay people and monks and nuns—praying and prostrating by the entrance to the Jokhang Temple.

Many Tibetans in Lhasa walk to the Potala Palace every morning at dawn and then make a circumambulation of the palace and the hill on which it stands. Some take the time to turn the prayer wheels that are mounted on the whitewashed walls of the route; others just stride briskly along, saying prayers as they work their way through a rosary of prayer beads or spin their handheld prayer wheels.

But the crowd is much heavier on Wednesday mornings, thick like at a country fair. People are more dressed up, in a version of “Sunday best.” When I returned to Lhasa recently and saw the crowd on my first Wednesday there (I was out taking photographs), I had no idea what the story was. There was a huge throng of people prostrating to the Potala or fingering prayer beads and praying as they walked. Later someone at my hotel explained it to me: the Dalai Lama was born on a Wednesday, so now Wednesday has become the day of the week that almost everyone makes the Potala circumambulation. It’s a quiet form of pro–Dalai Lama expression.

Once they’ve completed their circuit or two of the Potala (each time around takes about half an hour), many people stop in for a hot tea and a sweet bread twist (see Tashi’s Doughnut Twists, page 334) at one of the small food stalls by the circuit route. I stood there sipping my own tea, warming my hands on the cup (the air was chilly at that early hour), and watching the absorbed faces of the Wednesday-morning crowd. N

Eight-Flavor Tea, with dried pineapple, dried mango, goji berries, Chinese red dates, golden raisins, dried apricot, and rock sugar.

This treat is refreshing in the heat and warming in the cold. I first tasted eight-flavor tea on a sunny cool morning in Xining and was delighted by it. It looked so beautiful in the tall glass it was served in, the various dried fruits colorful and intriguing.

These days there’s an instant version of eight-flavor tea that is widely sold in China. We prefer to make our own, easily done since all the ingredients are long-keeping pantry items. The ingredients have good flavors and many also have medicinal properties. The dried fruits are there for both sweetness and tartness. We’ve suggested substitutions here, for there are actually more than a dozen possible ingredients that can make up the eight flavors. What you include depends on what is available and your own preferences.

The less familiar dried fruits, such as dried lychees, wolfberries (known as goji in Tibetan), and Chinese red dates (also known as jujubes), can be found in Chinese groceries and Chinese herbal food stores. Wolfberries are orange-red, small (the size of a raisin), smooth-skinned berries with a slightly sweet taste; they are traditionally thought to be good for the eyes and the blood. You’ll notice that they are also an optional ingredient in the water used to boil savory dumplings (jiaozi; see page 150). Red dates are sometimes included in soup (see Black Rice Congee, page 167); unlike regular dates, they are not eaten raw. They have a mildly sweet taste and are thought to be good for circulation and for the skin.

The water in the desert areas of western China is always a little salty tasting. The salt is welcome in the dryness, and in this drink in particular, salt seems to intensify all the other flavors. We call for a pinch of salt in each serving; try it this way, or do without, as you please.

Serve the tea in tall glasses, to show off the different colors of the “flavors,” with long-handled spoons or swizzle sticks, so guests can stir the sugar as it melts in the hot tea. It’s pleasant to drink the tea through a wide straw. The recipe is written for 1 serving; if serving 4, for example, put on a large pot of water, multiply the amounts by four and then distribute the tea leaves and flavorings among the glasses. And, as your guests drink their tea, bring another pot of water to a boil, so that you can top off each glass. Surprisingly enough, in our experience the second glass tastes as pleasing as the first.

FOR EACH SERVING

1½ cups water

1 teaspoon green tea leaves, or black if you prefer

5 to 8 wolfberries (see headnote)

3 Chinese red dates (see headnote)

2 dried lychees

2 to 5 golden raisins

1 slice dried pineapple, dried mango, or dried peach

2 dried apricots or dried plums

A pinch of salt

1 lump rock sugar (see Glossary), or to taste, or regular sugar to taste

Bring the water to a boil. Meanwhile, place the tea leaves and then all the other ingredients in a tall glass or in a glass cup.

Place a metal spoon in the glass (to prevent the glass from cracking when you add the hot water), and add the boiling water. Stir, then let stand for 5 minutes to allow the tea to steep and the dried fruits to soften.

Sip through a straw if you wish, stirring occasionally to help dissolve the sugar.

Cookies of various kinds have long been available in China, and packages of cookies find their way to remote corners beyond the Great Wall. Our dear friend Dawn-the-baker, an intrepid cook and traveler, came across shortbread with poppy seeds when she was in Yunnan in the spring of 2000. We asked her to figure out a version of it for this chapter, and here it is, delectable and attractive shortbread, flavored with ingredients local to southern Yunnan: poppy seeds and green tea.

The recipe calls for butter, but in Yunnan lard is the more available and local shortening; substitute lard for the butter if you wish. Use any green tea you like, and grind it to a powder in a food processor or spice grinder, or using a mortar and pestle. The tea gives the rich sweet shortbread an enticing bitter edge.

½ pound (2 sticks) unsalted butter, well softened and cut into small chunks

½ cup sugar, plus 2 tablespoons for topping

Generous ¼ teaspoon salt

1¾ cups all-purpose flour

½ cup plus l tablespoon rice flour

2 tablespoons finely ground green tea (see headnote)

¼ cup poppy seeds

Position a rack in the center of the oven and preheat the oven to 325°F.

Using a mixer on medium speed, cream the butter, the ½ cup sugar, and the salt until pale and fluffy. With the mixer on low speed, gradually add the all-purpose flour, rice flour, tea, and poppy seeds. The dough should start to come together like moist pie pastry and form into clumps. Alternatively, if using a wooden spoon, cream the butter, ½ cup sugar, and salt in a bowl until pale and fluffy. Gradually add the flours, tea, and poppy seeds, beating well after each addition, until the dough is well blended and forming clumps.

Press the dough into a 9-inch square baking pan, removing any air pockets. Prick with a fork, pricking right through to the pan, making rows of marks spaced ½ inch apart. Then cut into fingers 1½ inches by ½ inch or into 1-inch squares.

Bake until the edges of the shortbread pull away from the sides of the pan and the top is touched with brown, 30 to 35 minutes.

Cut the shortbread again while still in the pan. Sprinkle on the 2 tablespoons sugar, then carefully lift the shortbread out and place on a rack to cool.

Makes about 100 shortbread fingers or about 80 small squares

Stalks of sugarcane.

I didn’t quite believe it at first when I saw them for sale in the Jinghong market in spring 2006: 761 bars! They are now labeled 781, but there was no mistaking the packaging, no mistaking the contents. We’d practically lived on 761s over the course of five long trips in Tibet in the 1980s, and we’d once seen them for sale, bizarre as it was, in Vietnam (Vietnam and China were at war at the time). But 761s don’t otherwise travel all that much.

We never learned the full story about 761s. The picture of the army man on the label was a quick giveaway that 761s are Chinese army rations, but their contents have always been a bit of a mystery. Inside each package are four extremely dense shortbread-like bars, only less sweet. Ingredients are wheat flour, sugar, fat, and not much else. They’re good, but not necessarily something we’d put out for guests at home. They are, as I said, very very dense.

In Tibet, we would eat them in the morning with instant coffee that we’d make from the thermoses of boiled water provided in each room, even in the most remote truck-stop hotels. And we’d have 761s as midday snacks, sometimes even for lunch if there was nothing else around. I can’t remember how we first thought to buy them in the Lhasa market, because the packaging doesn’t automatically register as food. They also weigh a lot, more like a bar of yellow laundry soap than something you would eat. But however we discovered them, they became an important part of life.

On our first bicycle trip in 1985, we ate them all day long, as we were almost always low on calories. Eating a 761 was like eating four granola bars compacted into one, and sometimes we’d open a package thinking we’d eat just one bar and then end up eating all four. There was a little wrinkle about the manufacturing date, because each package had a date—maybe 1982 or 1983. But they never tasted stale, and we’d always buy up as many as we could find, no matter what the date. I don’t know what we’d have done without 761s.

So anyway, there in the Jinghong market, twenty years later, I bought two packages of 781s. I resolved to eat one and take the other one home to show Naomi. A few days passed. I was no longer in Jinghong, and I was having a coffee. I opened a package and had a bite, then another bite.

It had been a mistake, buying just two packages. J

A portrait of 781 bars, taken in Yunnan.

Kaili, Guizhou: Here I am in the next-to-last seat in the bus. It’s a familiar feeling. We won’t leave until the bus fills, and we’re still five or six people short. Meanwhile, I write in my journal and watch the scene. There’s a Miao mother across the aisle nursing her baby, and a pair of leather-jacketed young men just in front of me, smoking away. It’s supposed to be a six- to eight-hour ride to Congjiang, the town I’m aiming for tonight, and then tomorrow I’ll have another two hours on bad roads to get to Zhaoxing, the big Dong village where I want to spend a chunk of time.

Ah, the driver’s starting the bus. At last, we’re off….

No, not yet, after all. The bus driver turns off the engine, climbs down from the bus, lights a cigarette.

Stragglers hustle into their seats. Parcels get stowed in the small racks overhead.

I have a window seat, and the window is a large one that opens wide: such a treat, the fresh air, the clear view, and the chance to escape most of the cigarette smoke.

Now, once again, the driver starts the engine. This time we really are leaving.

We make our way through the streets of Kaili. My neighbor, a young guy dressed in black, offers me a hard candy. We begin to head south through the steep green landscape. A child waves to the bus from the side of the road. I wave back, and my heart lifts. Good-bye bus-stand blues. N

Young children, hardy and lively, in the bright cold air of Tingri village, in early November. Across a wide open plain, Mount Everest and its neighboring peaks, including Cho Oyu, are dazzlingly visible when the sky is clear.

Tashi’s Doughnut Twists, with a glass of sweet tea.

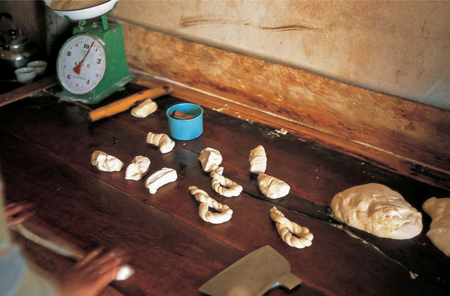

In Lhasa, and in smaller Tibetan towns in Sichuan, Gansu, and Qinghai, you’ll see stacks of these deep-fried treats for sale, especially in the morning. Bakers make them and sell them by the handful. The Tibetan name for them in Labrang is gori maro. Our younger son, Tashi, has loved them since the first time we made them. They’re slightly sweet, a rich golden brown on the outside, and tender in the center, a pleasure with morning tea or coffee.

The shaping puzzled me until I spent time hanging out at a Tibetan bakery in Labrang watching the dough get transformed into double coils. The instructions look long, but once you’ve shaped one, you’ll understand the sequence and then it will all happen easily. Each piece of dough is rolled out to a long, thin snake that then gets twisted on itself twice before being slipped into the hot oil. We often shape and bake half the dough one day, leaving the rest for the next day (see Note on Timing).

Make these for breakfast or for brunch, or as a late-afternoon snack for a hungry crowd.

3 cups all-purpose flour, plus extra for surfaces

½ cup sugar

½ teaspoon salt

1½ teaspoons baking soda

About 1¼ cups lukewarm water

Peanut oil for deep-frying (2 to 4 cups), plus extra for surfaces

If using a food processor, place the flour, sugar, salt, and baking soda in the processor. With the blade spinning, slowly pour the lukewarm water through the feed tube until a ball of dough forms. Continue to process for 15 or 20 seconds. If working by hand, combine the flour, sugar, salt, and baking soda in a large bowl. Stir to mix. Make a well in the center and add 1 cup of the water. With your hand or a wooden spoon, stir the water into the flour mixture until all the flour is moistened; add more water if necessary. Knead in the bowl until you have a dough.

Turn the dough out onto a lightly floured surface, then knead it for several minutes, until it is very smooth and elastic. Cover with plastic wrap and let stand for an hour or so. The dough will soften and expand a little as it rests.

Lightly flour a work surface. Lightly oil a nearby surface.

Using a dough scraper or a large sharp knife, cut the dough in half. Set half aside, loosely covered. Working on the floured surface, cut the remaining dough into 8 equal pieces, cutting it in half and then in half and half again (each piece will weigh about 1¾ ounces). Roll one piece under your flattened palms, pressing outward slightly as you do so, into a long rope. The rope will gradually lengthen under your hands; once it is about 10 inches long, set it aside for a moment and start to roll and stretch a second piece in the same way. Come back to the first piece (the dough will have had time to relax a little) and roll it until it is 18 to 20 inches long.

Move the long rope onto the oiled surface. Anchor one end of it on the work surface with one thumb and roll the length of it under the palm of your other hand, rolling always in the same direction, so that gradually it twists more and more. When it is well twisted, pick up one end of the rope in each hand and bring the ends toward each other. The loop of rope will coil on itself. Pull on the bottom loop of the coiled dough to lengthen it slightly, then lightly press it flat on the oiled work surface. Once again anchor one end of it, the one with the two ends of dough, and use your other palm to roll the dough in the same direction as the coils that are already there, in order to twist it further. Lift up both ends and bring them toward each other. The loop will again coil on itself, slowly, making about one and a half twists. Bring the ends together and tuck the open end into the loop of the other end, then pinch to secure it.

The double-twisted dough will be about 4 inches long. Place it back on the oiled surface and press down lightly. Set aside on an oiled baking sheet while you shape the remaining 7 pieces, then divide and shape the other half of dough into another 8 twists (see Note on Timing). Set the sheet of shaped twists near your stovetop.

Place a large wok or deep heavy pot on your stovetop; make sure the wok or pot is stable. (Or use a deep-fryer.) Pour 2 inches of oil into the wok or pot and heat the oil over high heat. Set out a slotted spoon or mesh skimmer. To test the temperature of the oil, hold a wooden chopstick vertically in the oil, touching the bottom of the pan. If the oil bubbles up around it, it is at temperature. If it really sizzles or starts to smoke, the oil is too hot; lower the heat slightly and test it again. (A deep-fry thermometer should read 325°F to 350°F.)

Slide in one shaped twist. It will sink, then slowly rise back up. After about 30 seconds, use the slotted spoon or skimmer to gently turn it over. It should be golden, not dark brown. (If the doughnut darkens more quickly, your oil is too hot, so lower the heat slightly; see Note on Troubleshooting.) Let cook for another 30 seconds, then turn it back over. The second side should now be a medium brown. Cook for another 20 seconds or so on each side, or until the doughnut is medium to dark brown. You will see attractive pale lines where the twists cross over. Use the slotted spoon or skimmer to lift the twist out onto a paper-towel-lined plate.

Repeat, this time starting with one twist and then adding a second if your pot is large enough, when you turn it over for the first time. Cooking times will be a little longer when you cook 2 or more at a time. Cook the remaining shaped twists in the same way. Allow to cool for several minutes before serving.

Makes 16 twists, 4 to 5 inches long; serves 8 as a snack or for breakfast

NOTE ON TROUBLESHOOTING: If the oil is too hot, the outside of the twists will quickly turn a rich dark brown and crust over before the center has cooked; if this happens, lower the heat slightly before putting in the next dough twist.

NOTE ON TIMING: You can shape and cook half the dough, then refrigerate the remaining dough, wrapped in plastic, for as long as 24 hours. The process of dividing and shaping the dough will eventually warm it to room temperature, but the cool dough ropes will probably take a little longer to stretch.

In the village of Labrang, not far from the monastery, there’s a small bakery. Every day the baker shapes and cooks stacks of doughnut twists. Here some of the dough has already been shaped and is ready to be dropped into the hot oil, while at the lower left, the baker’s hands are shaping yet another twist.

A monk outside one of the large temples at Labrang Monastery in Gansu.

A traditional Tibetan house in western Sichuan, set in fields where cattle graze.

“No, there’s no mare’s milk in this region,” said Ma Yun Da Lai, an expert in Mongolian milk products. “That’s only in the western regions. Here we have cow’s milk.” I met Mr. Ma in the small city of Yakishi, in the northern part of Inner Mongolia, where he has a small laboratory. He was working to develop a liqueur made from milk.

As a person who happens to dislike the taste of milk, I had a feeling of dread when he poured me a wineglass of the milk liqueur. Oh no, I thought, another of those moments when you just have to hold your breath. I took a cautious sip…. It was a delicious surprise, mildly alcoholic, and definitely not milky tasting. I was reminded of Bailey’s Irish Cream and said so. Mr. Ma smiled broadly. I asked if koumiss, the traditional Mongolian drink made from fermented mare’s milk, had inspired the liqueur. “No, not really. Koumiss is fermented and this is distilled. In fact, I was more aiming for the taste of Bailey’s,” he said, pulling out a bottle. We laughed, then tasted the Bailey’s and the milk liqueur side by side. The Bailey’s was sweeter and more alcoholic; the milk liqueur was more aromatic, and definitely my favorite of the two.

It had been a day of new tastes and new ideas. Earlier, at lunch, I’d been offered a local berry wine, pale pink, light (about 5 percent alcohol), slightly aromatic, and not at all sweet. It’s called lam mei cu (pronounced “lam may tsu”) and known by its initials, LMC. I was with some people from Yakishi who had generously decided to take me to lunch.

Every once in a while someone would raise a glass. Then we’d all raise our glasses and drink together, not in a “bottoms-up” way, but sipping as we wished, the wine a good accompaniment to the simmered elk and other local dishes on the table. The wine is made from cloudberrylike berries that grow in the mountains nearby. So far it’s not available except in Yakishi. To my regret, I couldn’t even find a bottle in Hailar to take home with me. N

The contents of a Mongol home, a ger, waiting for the frame and covering to be erected around them. The Mongol families who live out here on the Hulun Buir grasslands (north of Hailar in Inner Mongolia) move every fall to be closer to the river.

Tibetan Rice Pudding, made with small pieces of dried apple.

This delicious version of rice pudding, known as de-sil in Tibetan, uses broken rice (the lowest grade of rice; see Glossary), which is ideal for the pudding because the broken grains release starch as they cook, creating a thicker, smoother texture.

In Tibet, there’s a little brown root, rather like a miniature yam, that is gathered in the wild and then dried. Small piles of it are for sale in the markets, and it is traditionally used as a sweet flavoring in this rice pudding, sometimes in combination with raisins from Xinjiang. We substitute dried apple, chopped into small pieces, for the Tibetan root, and we skip the raisins, as we prefer to let the subtle perfume of the apple stand on its own. Do feel free to substitute golden raisins for some or all of the dried apple if you wish. The other sweet flavoring is honey. Use a pale, clean-tasting flower honey.

Serve the pudding in small bowls for dessert or as a snack, either plain, or drizzled with a little more honey or butter or yogurt, or a combination. Leftovers make a welcoming breakfast (see Note).

3 cups water

1 cup broken rice

Pinch of salt

3 cups whole milk

½ cup packed dried apples, preferably organic, chopped into ½-inch or smaller pieces

3 tablespoons clover honey or other flower honey, or more to taste

2 tablespoons butter, or to taste (optional)

Bring the water to a boil in a small heavy pot. Place the rice in a sieve and rinse with cold water to clean it, then sprinkle into the boiling water. Bring back to a boil, then lower the heat to medium-low and cook, covered, until most of the water is absorbed and the rice is soft, about 15 minutes.

Add the salt, then stir in the milk and apples. Raise the heat and bring back nearly to a boil, then reduce the heat to very low, cover, and simmer for 45 minutes to 1 hour, stirring occasionally with a wooden spoon to make sure the rice is not sticking; after about 30 minutes, add the honey and stir in. When cooked, the pudding will be very thick.

Just before serving, stir in the butter, if using.

Makes about 6 cups; serves 6

NOTE ON REHEATING: If left to stand for any time after cooking, the pudding will thicken even more. To reheat it or to loosen the texture, place over low heat, and stir in up to 1 cup more milk (as well as the optional butter). Stir frequently as the pudding warms, to prevent sticking.

In our travels beyond the Great Wall, we can’t remember a time when we wanted a beer and couldn’t find one. We could be in a village at 15,000-feet elevation in far western Tibet, and there’d be beer to drink with dinner. Or we could be in a small predominantly Muslim village in Xinjiang, and sure enough there’d be beer, tall brown or green glass bottles of beer. Beer is almost everywhere, which is remarkable, but how it gets there might be even more remarkable.

Once we were traveling by truck through the Changtang, the high desolate region of western Tibet, a region where you can drive all day and never see another vehicle. Late one afternoon, we reached a tiny “truck stop,” where we were going to spend the night. Far in the distance we could see a large old truck making its dusty way across the landscape, traveling about ten to fifteen miles per hour, bumping, shifting gears, lurching along. Finally it got to the truck stop and came to a shuddering halt in the middle of the road. People suddenly started to appear from nowhere. Soon boxes of beer were being tossed off the truck and money was changing hands. We too rushed to the truck, grabbed several cases of beer, and paid the wild-eyed driver for it. A few minutes later, he got back in his cab and the truck drove off, slowly grinding its way along the dirt road, bottles clinking and clanking.

There’s booze other than beer beyond the Great Wall, but most of it’s local. We once stayed in a guesthouse in Menghan, in southern Yunnan, sleeping on a mattress on a slatted wood floor in a beautiful Dai post-and-beam house built on stilts. It was a great place to stay, and the food served at the guesthouse was some of the best food we’ve ever eaten in Southeast Asia. The only problem was that we had a hard time sleeping because we could hear constant commotion all night from chickens perched on the wooden beams just beneath our room. One morning, when we went to look at them, we realized that, apart from the chickens, we were sleeping over the brewing area: twenty or thirty enormous earthenware vats of local rice liquor, rather like sake, were down there fermenting by the hour in the tropical heat.

Liquor made from rice and other grains is common throughout Guizhou and Yunnan. Like lao khao (rice liquor) in neighboring Thailand and Laos, it is fermented but not distilled; it has a very easy, nice taste and seems to have a little less alcohol than wine. The same is true for the common local drink in Tibet, chang, which is most often homemade from barley and usually served in bowls.

Guizhou is famous as the home of China’s most well-known distilled liquor, Mao Tai. Mao Tai, like many types of Chinese commercial liquor, is made from sorghum and is extremely strong, much stronger than Western whiskeys. We can tolerate Mao Tai, but just barely. It tastes too much like baijiu (white liquor), a generic Chinese firewater that is almost as ubiquitous as beer but much more lethal. One kind of Chinese liquor we like a lot, a dark medicinal drink made from millet, is called Wu Jia Pi. If you ever see it for sale, buy a bottle and try it, a taste of far away.

In the rural markets of Guizhou, there’s always a laneway or alley where men buy and sell tobacco. Since before buying one must sample the tobacco on offer, the men are couched on their haunches smoking small stone pipes of tobacco as they examine the cured leaves of tobacco for sale.

The Pamir Mountains at the far western edge of Xinjiang province are home to the small population of Tajik people who live in China. They number approximately 42,000 and live in a small area that extends from just north of the old frontier village of Tash Kurgan south to the Pakistani frontier. In neighboring Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and the upper Hunza Valley of Pakistan, there are about fifteen million Tajiks. Unlike the other peoples in Xinjiang, who speak Turkic languages, the Tajiks speak an Indo-European language that is related to Persian. The Pamir Tajiks include smaller groups who speak Wakhi and other Iranian languages.

Younger Tajik women wear their hair in many long braids down their backs, decorated with buttons down their length. It’s a striking and attractive look. A Tajik woman in the small town of Tash Kurgan told us that once a woman has had a number of children, she has no time for the elaborate braiding required and then just keeps her hair in one or two braids, with no decoration. The women’s brightly colored cotton dresses are worn over leggings or pants, and they cover their heads with colorful caps or scarves.

The Pamirs are high snow-capped mountains separated by broad U-shaped valleys. Because of the elevation, and the winds that blow nearly year-round, the agricultural season is short and not much can be cultivated. The Tajiks keep herds of sheep, goats, and camels, which graze on the sloping treeless pastures on the flanks of the mountains. These days, in winter most Tajiks live in small hamlets or villages in houses built of stone, but in summer many live in yurts and move with their herds from grazing ground to grazing ground.

The town of Tash Kurgan is an overnight stop for trucks and buses traveling the Karakoram Highway (between Kashgar and Pakistan’s Hunza Valley). It’s the modern version of the role the town had for centuries as a frontier post on the old Silk Route. There’s an old fort at the edge of town (see photo, page 5); you can climb up to the ruins, get a view of the valley, and imagine the era of Marco Polo. Because of the business generated by the road, we suppose, Tash Kurgan has several bakeries, run by Uighurs, and restaurants and inns, run by Han or Uighur people.

The Tajik houses and yurts that we have seen are very inviting spaces. The houses are rectangular or square and the yurts round, but both usually consist of one large room divided into separate spaces by different floor levels. In the center is a tandoor oven, below a smoke hole in the roof that also lets in light. A higher floor is built to one side of it as a sitting and living area, and against the far wall are stacked folded quilts and blankets. Another area, at yet a different floor level, is the food preparation/kitchen space, where sacks of flour and other staples are stacked against the wall.

The staples of the Tajik diet are breads made of wheat flour; goat’s or sheep’s milk; yogurt and butter made from the milk; tea; and, on rare occasions, meat. The other outstanding Tajik staple in our experience is hospitality (see “The Pamirs, June 1986,” page 141).

A mother and child in the village of Dafdar, along the Karakoram Highway in the Pamirs; a weathered man in Kashgar; a Tajik family who welcomed us into their small house in Dafdar. (The sunlight is coming in through the open smoke hole in the roof, which is right above the family’s tandoor oven.)

A weathered man in Kashgar.

A Tajik family who welcomed us into their small house in Dafdar. (The sunlight is coming in through the open smoke hole in the roof, which is right above the family’s tandoor oven.)