An assortment of rices–including several grades of jasmine rice, white sticky rice, and red and black rice–for sale at the market in Jinghong, in southern Yunnan. The colored rices may be used for congee or sweets, or as the basic mash for making rice liquor.

We love best the foods we can rely on and eat with pleasure day after day, the comforting, undemanding flavors and textures of staple grains. For some, that translates into a passion for bread, but for people living beyond the Great Wall, it often means an intimate relationship with rice, millet, or barley, or with noodles. (The noodle connection is so huge that noodles have their own chapter, as do breads.)

We begin with instructions for cooking plain rice of two kinds: sticky rice, the traditional staple for many peoples living in southern Yunnan and in Guizhou and parts of Guangxi province, and jasmine rice, which is our everyday rice.

An alternative to plain steamed rice is rice—or another grain—cooked to a thick porridge texture. It can be eaten to anchor a meal, as plain rice is, or instead served with toppings and condiments for breakfast or a snack. The word used in English for grains cooked with lots of water to a soupy texture is sometimes “porridge,” or it may be “soup.” Another word often used is “congee,” from the Hindi kañci, meaning a rice porridge. Rice congee is a staple food in many places in Asia (Japan and Thailand, for example, as well as China), usually made very plain, sometimes cooked up with mung beans, as we have it here (see page 173). At breakfast or as a late-evening snack, it’s served with an array of savory toppings and flavorings, from chopped pickled vegetables to salted peanuts, chopped grilled meat, and seasonings. Though many North Americans may not be used to the idea of pickled greens and other strong savory tastes for breakfast, for those who love it, congee is comfort food, easy to spoon down and warming. Other grains have their place in the congee world too, especially in areas where rice is a luxury. We’ve included a millet congee (see page 172), which we like as an accompaniment at supper in place of plain rice, and also a dramatic-looking black rice congee (see page 167).

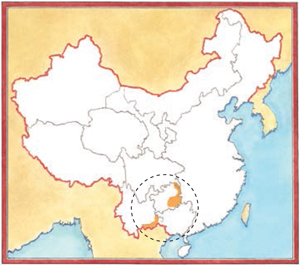

In Xinjiang, many people, including the Kazakhs (see page 157) and Uighurs (page 90), have a tradition of festive rice dishes in the pulao tradition (see Chicken Pulao with Pumpkin, page 174; and Kazakh Pulao, page 177). Flatbreads and noodles are the everyday staples, made with wheat grown in the oases, but pulaos are the dishes for special occasions, served on large platters, family-style. The rice is simmered in broth with meat and vegetables and aromatics, absorbing flavor as it cooks. These pulaos are part of the flavored rice tradition that extends from Central Asia to the pulaos of Mogul India and the eastern Mediterranean, the paellas of Spain, and the pilafs, pulaos, and perloos of West Africa and South Carolina. They are best made with Mediterranean varieties of rice; we suggest baldo or arborio or Valencia, which have a generous capacity to absorb the flavored broth and yet keep their shape.

The last section of the chapter is devoted to tsampa, the amazing Tibetan staple that is an ingenious solution to the challenge of making edible food from hard grain. Barley grows only in the valleys of Tibet, so the high-altitude nomads trade meat and salt for barley tsampa. Tsampa is lightweight, keeps well, and needs no further cooking, no further fuel, to make it digestible. With access to a good coffee grinder or, better still, to a flour mill, we’ve found we can make it at home, a great discovery.

Sticky Rice with Dai Tart Green Salsa (page 22).

The Dong (see page 120), like the Dai (page 237) and many other Tai peoples, are traditionally sticky rice eaters. Even though sticky rice is now more often a festive food than an everyday staple for some families, it’s still an important mark of identity.

This was brought home to me when I stayed in the Dong village of Zhaoxing, in eastern Guizhou. The schoolteacher daughter of one of the families I met there had married a Han man, also a schoolteacher. He was one of very few non-Dong in the village. And one of the ways that he kept his separate identity, apart from not speaking the Dong language (he and his wife spoke Mandarin together), was that he did not eat sticky rice. The family made large batches of sticky rice while I was there, once for the name-giving party for a cousin’s baby, the other time for a celebration that marked the opening of their new guesthouse. On both occasions the daughter was very careful to say to me, “My husband and I don’t eat sticky rice.”

Sticky rice is a special variety of rice (also known as glutinous rice), with opaque white grains rather than the translucent grains of most raw rices. It’s now widely available in Asian grocery stores. The sticky rice in Japan is short-grain, but the rice used by the Dong and Dai is like Thai and Lao sticky rice, medium- to long-grain. Look for bags labeled “sweet rice” or “glutinous rice” and “product of Thailand” (for more, see Glossary). Sticky rice has relatively little capacity to absorb moisture (unlike risotto rices, for example, or basmati) and is usually cooked by steaming after being soaked in water overnight.

With the increasing popularity of Southeast Asian cuisines, especially Thai and Vietnamese, more and more people in North America have now eaten sticky rice, at least in a restaurant. What many people don’t realize is how easy and forgiving it is to cook: no measurement of water and rice, just a long soak in water and about 35 minutes steaming.

The Dong and the Dai, like many people in northern Laos, steam their rice in wide bamboo cylinders over boiling water. In North America, you can steam the soaked rice in a regular Chinese bamboo steamer, after lining the rack with a tea towel to prevent the rice from falling through the slats, or you can use a Lao-style conical basket placed on the rim of a pot.

Show your guests how to pick up a small clump of sticky rice in one hand and then tear off a little of it, as you’d tear a bite-sized piece from a slice of bread. Shape it into a firmer ball and scoop it through a savory sauce, such as Dai Tart Green Salsa (page 22), or use it to pick up a small piece of grilled fish or meat.

3 cups Thai sticky rice (see headnote)

Rinse the rice briefly to wash off any dust. Place in a large pot and add about 6 cups tepid water. Cover and set aside for 10 to 12 hours to soak. (If you are in a rush, you can hurry the rice by soaking it in warm water: don’t make the water boiling hot, just very warm, and reduce the soaking time to 4 hours. Longer soaking produces a slightly better texture.)

Drain, then place the rice in a steamer—a conical or round sticky rice steaming basket if you have one (see headnote), or a regular Chinese bamboo steamer lined with muslin, cheesecloth, or a loose-weave tea towel so the rice doesn’t fall through (see photo).

In either case, you need 2 to 3 inches of water in the pot under the steamer, and the rice in its basket must be above, not in, the water. A conical or cylindrical basket should fit tightly into the pot (so the steam can’t escape around the sides). A regular steamer works best resting in a wok; otherwise, it should fit tightly over a pot of water.

Bring the water to a boil. If you are using a Lao steaming basket, then just cover the top loosely (it will cook uncovered, but we find covering it makes it cook a little more quickly and evenly) and steam for about 35 minutes. If you are steaming in a wide round steamer, cover tightly and steam for 20 minutes; remove the steamer and use a wooden spoon to turn the rice over, then place the steamer back over the boiling water and continue to steam for about 15 minutes. The rice should be tender but still firm when done.

Turn the rice out onto a counter or other surface and use a long-handled wooden spoon or spatula to spread it out and then to lift the sides in toward the center, to create a round lump of rice (this evens out the texture). Transfer to one or more covered baskets, or place in a bowl and cover with a well-moistened cloth to prevent the rice from drying out. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Makes about 6 cups; serves 4 to 6

STICKY RICE WITH CURED SAUSAGE: As the rice steams, flavorings can be cooked or heated on top of it. In Jinghong, we’ve seen Chinese sausage cut into pieces, steam-cooking on top of a large batch of sticky rice. To try this, buy about H pound Chinese sausage, rinse it, and cut it into H-inch lengths. Once the soaked rice is in the steamer, scatter the sausage on top, cover, and steam until the rice is done, as above. Serve the sausage separately, or mix it into the rice after steaming.

Sticky rice, once soaked, can be steamed in a number of ways. Here it is placed in a cheesecloth-lined steamer that is in turn placed over water in a wok (the water must not touch the rice). The steamer is then covered, the water brought to a boil, and the rice cooks to an even doneness in about half an hour.

In late autumn the rice has been harvested in these rice terraces not far from the Miao village of Xijiang in Guizhou province. What remains is the stubble, already flooded with water so that it can be plowed under and the ground readied for the next planting. The method of storing rice straw by stacking it on a pole to repel the rain is used by the Miao and Hmong we encountered, whether in China or in Southeast Asia.

Baskets of newly harvested rice, in the Dong village of Zhaoxing, also in Guizhou.

Most rice in the south of China is consumed very close to where it is grown. People have a strong feeling of attachment to the rice they grew up with, and though its flavor is subtle, everyday rice can vary a lot in flavor from place to place and variety to variety.

We use Thai jasmine as our everyday rice. You may have another favorite; use whatever medium- to long-grain rice pleases you. You will need a heavy straight-sided relatively wide (rather than tall) 3- to 4-quart pot, with a tight-fitting lid, or a rice cooker.

2 cups Thai jasmine rice

About 2½ cups water

To wash the rice, place it in a bowl or pot and add plenty of cold water. Stir the rice and water round and round with your hand, then pour off the water. Repeat two or three times, until the water runs clear after you have swished it around.

Transfer the rice to your rice-cooking pot or rice cooker. Add enough water to cover the rice by about ¾ inch. Test the depth of the water by placing the tip of your index finger on the top surface of the rice; the water should come up to the middle of your first knuckle. (This is the usual way of measuring water for plain rice in Southeast Asia and in the cultures we’ve been in in southern China. If you prefer a cup measure, drain the washed rice thoroughly in a strainer, then place in the pot with 2½ cups water.)

If using a pot, place the pot over high heat. When the water is boiling, cover tightly, lower the heat to medium-low, and cook for 10 minutes. Reduce the heat to the lowest setting and cook, covered, for another 6 to 7 minutes. Remove from the heat and let stand for 5 minutes, still covered.

If using a rice cooker, put the lid on and turn it on. (The cooker will automatically bring the water to a boil and then lower the heat and cook it until done. You will see an indicator light change color or turn off when the rice is done.) Once the rice is cooked, let stand for 5 minutes, covered.

When you remove the lid from the pot or rice cooker, you will see that the grains on top have fluffed and are standing on end.

Rinse a wooden rice paddle or wooden spoon with cold water and slide it down the side of the pot, then tilt to lift up some of the rice gently and turn it over. Repeat all around the sides of the pot.

Serve hot or warm. Leave the lid on, to keep in warmth and moisture.

Makes about 4 cups; serves 4 to 6

NOTE ON SCALING UP: To make a larger quantity, to serve 6 to 8, or because you’d like leftovers, use 3 cups rice. Add water using the same fingertip measure as above, or add 3¾ cups water to the well-drained rice. Cook as above.

A fairly prosperous Han woman farmer in Inner Mongolia, north of the town of Yakishi and not far from the border with Siberia. She and her husband are tenant farmers who grow barley, millet, and vegetables and raise chickens. In the summer they also have a small farm-stay business, where guests come to stay for up to several weeks. When we dropped by in late October, she was busy pickling cabbage in preparation for winter. In her kitchen was a large tiled stove fueled by charcoal that is used for cooking and also for heating the house. The family’s electricity comes from a small solar panel; it’s enough to power the television and several lightbulbs.

This purplish black version of rice porridge/congee can be served for breakfast or as a rice dish at any time. It’s especially attractive when sprinkled with a fresh green herb, such as chopped coriander leaves. Black rice congee is made of black sticky rice mixed with either rice brokens (broken rice grains; see Glossary) or white rice such as jasmine. The black rice stains the white rice grains a beautiful purple. In China, black sticky rice is grown in the southern provinces of Guangxi and Guizhou. Black sticky rice from Thailand is widely available in North America.

Chinese red dates, also called jujubes, are available at Chinese grocery stores and at some health food stores. Like wolfberries, they’ve recently come to the notice of Westerners because of their health properties. Cooks in China add them to soups because they are believed to be good for circulation and for the skin. (see Glossary for more on Chinese dates.) They have a slight sweetness and are pleasant little nuggets of flavor to discover as you eat the congee, but they can, of course, be left out.

Serve black rice congee with savory flavors such as a chopped cucumber salad or, nontraditionally, chopped avocado dressed with fresh lime juice. For a sweet alternative, see Coconut Milk Black Porridge below. [PHOTOGRAPH ON PAGE 170]

About 6 cups water

½ cup black sticky rice, washed and drained

¼ cup rice brokens or medium-grain rice such as Thai jasmine, washed and drained

¼ cup Chinese red dates (see headnote; optional)

Bring 6 cups water to a vigorous boil in a wide pot. Sprinkle in the rices and bring back to a vigorous boil. Lower the heat and cook at a medium boil, partially covered, for 15 minutes, then add the dates, if using, and cook for another half hour or until the rice is very soft and starting to break down. Stir occasionally to prevent sticking, and gradually lower the heat as the congee cooks, to prevent scorching. If it is getting very thick but is not yet cooked, add another cup or so of water, bring back to a boil, and continue cooking.

Serve hot.

Serves 4 as part of a meal

COCONUT MILK BLACK PORRIDGE: For a lusher version, and one more like our Western idea of porridge, cook the congee as above, but serve it with sweetened coconut milk: Heat 2 cups canned or fresh coconut milk and dissolve about ½ cup packed brown sugar in it. Put the sweetened coconut milk in a small jug and invite your guests to pour it generously onto their congee (or you can stir some of it into the rice before serving it). You might also want to offer slices of fresh fruit (bananas or pears, for example) or berries.

We were in China three times in the 1990s, twice in Yunnan. The first time was in March 1994. I was in Vietnam, visiting a friend. He had heard that the China-Vietnam border—so long inaccessible—was now “open” for foreigners. I got a Chinese visa in Hanoi, then caught a train into the mountains of northern Vietnam. I stayed in Sapa, a village with an amazing mix of tribal cultures. It was rainy there, and I was carrying heavy camera equipment as usual. One day my knee went out and swelled up like a pumpkin. Ice bags didn’t exist in Sapa, so I used cold beer bottles to reduce the swelling, Chinese beer.

A young man gave me a ride on the back of his motorcycle, four hours down a muddy winding road, from Sapa to the China border. There was a train waiting on the other side, across a long bridge over a big river. It felt like a scene from a World War II movie: my bad knee, the rain, the bridge, the train waiting on the other side. But the Chinese border officials told me the train wouldn’t leave until the next day and that I should stay in the hotel overnight. And so I did.

But it was not like any Chinese hotel I’d ever stayed in. I had a room to myself, not a bed in a dorm, a nice clean room. I turned on the television (a television, in China!) that night, and from deep in the mountains of the China-Vietnam border area, where just a few years earlier a war had been fought, I watched an NBA basketball game.

The next day, I caught the train to Kunming. It was a spectacular ride. The track followed the course of the Red River, through deep mountain gorges. High up on the mountainsides, I could see rice terraces on a huge scale, as vertical as any rice terraces I have ever seen. I knew that we were passing through entirely tribal areas, but I had no idea who the peoples were and getting off to explore was not an option.

Kunming, the capital of Yunnan, was a city I was familiar with, but it had changed a lot in the ten years since my last visit. A decade earlier, the large main streets had been jam-packed with bicycles, with only the very occasional car or truck. Now it was just the opposite. There were still a million bicycles, but they had their own lane on the side, and the street was crowded with vehicles. It was the same attractive city, with tree-lined streets and with great food, but quite transformed.

A few years later, we were traveling with our kids from northern Yunnan down to the Lao border, working on our Southeast Asian cookbook, Hot Sour Salty Sweet. In Jinghong, in southern Yunnan, we stopped in at a little travelers’ café run by a group of young Hani women (see page 316). It was a café that you might expect in Kathmandu, or by a beach in southern Thailand. The young woman waiting on our table spoke to us in English far better than our Mandarin. After our food arrived, she pulled up a chair and chatted with us. She was twenty, or maybe not quite, from Guangxi, far to the east. She’d come to Yunnan to work. She’d heard that Dali (a small charming town in Yunnan, 300 miles west of Kunming) was a “cool” place to work, but so was Jinghong, and Jinghong had a better climate, so here she was.

For decades, it had been impossible for Chinese citizens to choose where they lived. The Beijing government changed all that in 1993, probably to facilitate the movement of labor from the poorer north to the booming south. People immediately started to relocate from poorer areas to more prosperous ones. Some say it was the largest movement of people in history.

The China of the 1990s was a world away from the China of the ’80s.

A village set in the steeply terraced landscape of Yunnan, about one day’s drive south of Dali. In the rainy season the terraces will be green with growing rice plants.

A large steamer full of sticky rice from the amazing terraces just outside town, in Yuanyang, southeastern Yunnan.

Rice for sale at the market in Jinghong, in southern Yunnan.

Millet by the Bowlful topped with pickled mustard greens; Black Rice Congee (page 167) cooked with Chinese red dates; Rice Congee with Mung Beans (page 173) with Bright Red Chile Paste (page 18) and roasted salted peanuts.

Millet, like sorghum, was once a very important staple in northern China, eaten as a toasted grain or cooked like porridge. Although these days wheat has largely displaced it as a staple food, millet is still eaten as a toasted grain by many rural people in Inner Mongolia, we’re told. And some homely traditional millet dishes, such as this simple porridge, or congee, can still be found in contemporary China, even in the cities.

There was a particularly good millet congee in the northern Inner Mongolian city of Hailar. It was part of a breakfast buffet, and I found it wonderfully soothing food for a cold morning. Alongside were an assortment of pickles and spicy flavors to eat on or with the congee. We suggest putting out roasted salted peanuts, some chopped pickled mustard greens or Tenzin’s Quick-Pickled Radish Threads (page 25); a chile paste or some chile oil; and perhaps some Cucumbers in Black Rice Vinegar (page 83). Or instead you can treat the congee like Western-style porridge and top it with slices of banana or some berries, milk or yogurt, and perhaps a drizzle of honey.

Millet congee can also be served as a substitute for rice in a main meal, just as it was traditionally eaten in parts of northern China and in poorer mountain areas. We’ve become very fond of eating it this way, especially when we’re tired on a chilly evening, because it’s real comfort food, and solidly sustaining.

½ cup millet

5 cups water

OPTIONAL ACCOMPANIMENTS (see headnote)

About ¼ cup chopped pickled mustard greens (see Glossary)

About ¼ cup roasted salted peanuts

Bright Red Chile Paste (page 18), Guizhou Chile Paste (page 35), or store-bought chile paste, or Chile Oil (page 29)

Cucumber-Vinegar Sauce (page 83)

Wash the millet well in several changes of water.

Place the water in a large heavy pot and bring to a boil. Add the millet and return to the boil, then lower the heat to medium, cover, and cook until very tender, about 45 minutes.

Serve for breakfast with some or all of the suggested accompaniments. Or serve in place of rice to anchor a meal.

Makes 4 cups; serves 3 to 5 for breakfast or as part of a meal

MILLET POLENTA: If you cook the millet ahead, or if you have leftovers, you’ll notice that as it cools, it thickens into a solid mass. To reheat, place it in a pot, add about ½ cup water, and stir until the millet is hot. Millet was the staple in many of the areas of Italy that later turned to a New World crop, corn, for their staple grain, and we think that this property millet has of thickening to a breadlike texture when cooled must be the origin of polenta. For millet polenta, cook it as above, then spread it in a lightly greased baking pan. Drizzle on a little olive oil and bake in a 350°F oven for 30 minutes. Serve cut into slices as you would serve polenta.

This blend of white rice and whole mung beans (the small dried dull-green beans that are sprouted to make mung bean sprouts) is another classic version of porridge/congee. It’s an old and healthy combination, rice with legumes, easy to prepare, and reminiscent of the kitchree of the Indian Subcontinent, in which rice and dal are cooked and served together. We’ve come across rice-mung congee in various places, from Inner Mongolia to Guizhou.

It makes a great breakfast porridge, but we also like it for supper, served in place of plain rice and accompanied by savory dishes, just as we do with millet (see Millet by the Bowlful, page 172). The small tender beans are like darker dots in the pale rice and have a slightly firmer texture. Put the beans and rice on to cook an hour or more before you wish to serve the congee. Or, to make it for breakfast, cook it the night before, then reheat it quickly in the morning. The texture is like a thick porridge. [PHOTOGRAPH ON PAGE 170]

¼ cup dried whole mung beans

About 6 cups water

½ cup medium- or long-grain rice (jasmine or other—but not parboiled rice)

OPTIONAL TOPPINGS

Roasted salted peanuts

3 tablespoons chopped pickled mustard greens (see Glossary)

2 to 3 tablespoons Guizhou Chile Paste (page 35) or Bright Red Chile Paste (page 18) or store-bought chile paste

Soy-Vinegar Dipping Sauce (page 151)

About ¼ cup dry-roasted sesame seeds

Rinse the mung beans, put them in a large heavy pot, and add 4 cups water. Bring to a vigorous boil, then lower the heat to maintain a medium boil, partially cover, and cook until the beans are softened but not yet cooked through, about 30 minutes.

Wash the rice, and add it to the pot with 2 more cups water. Bring to a vigorous boil, then lower the heat, partially cover, and simmer for about 25 minutes, until the rice is very soft. Check the pot occasionally to ensure that there’s enough water and that the rice and beans are not sticking to the pot; add more hot water if necessary.

Serve the traditional way, with an assortment of the suggested toppings. Or serve in place of plain rice with a meal.

Makes about 6 cups; serves 4 with toppings, 4 to 6 as part of a meal

RICE-MUNG BEAN SOUP: This congee transforms easily into a flavorful winter soup: When it is done, add an extra cup of water to thin the congee, and bring almost to a boil, then lower the heat to keep it at a low simmer, partially covered. Heat 2 tablespoons peanut oil in a wok or heavy skillet over medium-high heat. Toss in 1 tablespoon minced garlic and stir-fry briefly, then add 1 tablespoon minced ginger and 1 or 2 dried red chiles and stir-fry for 10 seconds. If you’d like a meatier soup, add about ¼ pound ground pork or lamb and stir-fry until it has changed color. Add 1 cup diced tomato (fresh or canned), 1 tablespoon soy sauce, and 1 teaspoon salt and stir-fry until blended in. Add 2 teaspoons toasted sesame oil, then add to the hot rice soup. Taste for seasoning and add a little salt if needed. Pour into bowls and garnish each bowlful with about 1 tablespoon minced scallion greens or chopped coriander leaves. Serve hot.

Serves 4 to 6 as breakfast or as part of a meal

Chicken Pulao with Pumpkin

The Uighurs (see page 90) share with their close cousins the Uzbeks a delicious pulao tradition. Pulao or pilaf is the name for a rice dish that is cooked together with flavorings, most often including meat, and water, to make a generous one-dish main course. It’s a dish of celebration, for rice is a luxury food in the oases of western China, while bread and noodles are the everyday foods.

The pulao idea seems to have spread out from the sophisticated cuisine of Persia (Iran), radiating east along the Silk Road and west into Arab-held lands (and eventually through the Arabs to Spain, where it became paella). It also traveled south into Afghanistan and eventually to the Indian Subcontinent with the Mogul invaders. Along the way, it was adapted to local conditions in interesting ways.

In Uighur hands, pulao is most often cooked in a q’azan, a wide shallow wok-like pan. We use a wide heavy pot or sometimes a very large wok. As with paella or risotto, the flavor base cooks first, in oil, then water is added to make a broth. Finally the rice is added and cooks in the broth, absorbing flavor, to make a wonderful backdrop for the chicken and pumpkin here. Serve with a salad or two, say Onion and Pomegranate Salad (page 89), Cucumbers in Black Rice Vinegar (page 83), or Napa and Red Onion Salad (page 86).

2½ cups medium-grain Mediterranean-style rice, such as arborio, baldo, or Valencia

1 tablespoon salt, or to taste

About 4 pounds whole chicken legs and/or breasts

About ½ pound daikon radish

¼ cup peanut oil or vegetable oil

2 medium onions (¾ pound), coarsely chopped

2 medium tomatoes, coarsely chopped

4 cups water

About 1 pound peeled pumpkin or winter squash, cut into 1½-inch cubes

ACCOMPANIMENTS

¾ cup Jinjiang (black rice) vinegar or cider vinegar, diluted with ¼ cup water, or to taste

2 lemons, cut into wedges (optional)

Freshly ground black pepper

Rinse the rice well with cold water. Place it in a medium bowl with enough lukewarm water to cover it by an inch, stir in 1 teaspoon of the salt, and set aside to soak.

Remove the excess fat from the chicken. Finely chop about 3 tablespoons fat and set aside. Traditionally the skin is left on, for extra flavor and succulence; remove and discard it if you wish. Use a cleaver to chop the chicken into approximately 2-inch pieces, leaving the bones in. Rinse and set aside.

Peel the daikon and grate it on a coarse grater, or cut it into matchsticks (thinly slice it on a long diagonal, then stack the slices and cut into matchsticks). You will have about 2 cups. Set aside.

Heat the oil in a large wide heavy pot over medium heat. Add the reserved chicken fat and render it (over medium heat, the fat will gradually melt into the oil, leaving some small crispy cracklings). Once the fat has melted, scoop out the cracklings and save for another purpose (such as a topping for congee or for flatbreads). Raise the heat to high, and when the oil and fat are nearly smoking, add 1 teaspoon of the salt. Carefully slide the chicken pieces into the oil and start to brown them, turning occasionally. (If your pot is not wide enough, you may have to brown the chicken in 2 batches; then return all the chicken to the pot.) After several minutes, add the onions. Cook until the chicken is browned on all sides, then add the daikon and tomatoes and stir well. Lower the heat slightly and cook for about 5 minutes, stirring if the vegetables are sticking at all. The daikon should have softened and the tomato will be starting to disintegrate.

Add the water and the remaining 1 teaspoon salt, raise the heat, and bring to a vigorous boil. Lower the heat to medium and boil gently, partly covered, for 10 minutes. Taste the broth and adjust the seasoning if necessary.

Drain the soaked rice and sprinkle it into the broth. The liquid should cover the rice by ½ inch; add a little hot water if necessary. Bring to a boil, then cover tightly, lower the heat to medium, and cook for 5 minutes. The water will now be just level with the top of the rice. Distribute the pumpkin pieces over the rice. Cover tightly once more, lower the heat to very low, and cook for 30 minutes.

Remove the pot from the heat and let stand for 10 minutes before removing the lid.

Traditionally pulao is served on a platter, the rice mounded and then the pumpkin and chicken pieces placed on top, but we like to serve it straight from the pot. If you serve it on a platter, use tongs to lift out the chicken pieces and the pumpkin (the cooked cubes of pumpkin are very tender, so be careful not to mash them), and set them aside. Use a wooden spoon or spatula to mound the rice on the platter, then place the pumpkin and chicken pieces on top. Traditionally guests, after washing their hands, eat with their hands, helping themselves directly from the platter. If your guests are not comfortable eating this way, serve them individually, or put out several serving spoons so they can serve themselves from the platter, and provide spoons and forks to eat with.

Put out several condiment bowls of the vinegar, together with small serving spoons. Invite guests to drizzle a little vinegar onto their rice. If you like, put out wedges of lemon to be squeezed over the chicken and rice to taste, and put out a pepper mill.

Serves 6 as a main course

CHICKEN-QUINCE PULAO: Quinces are a common fruit in the Silk Road oases in the autumn. They look like knobby yellow apples and are very hard (see Glossary). They have a delicious sweet-acid flavor when cooked and, when available, are often used in Uighur pulaos as a foil for the meat. You can include 1 or 2 small quinces, peeled, cored, and cut into 1-inch chunks, instead of the pumpkin or in addition.

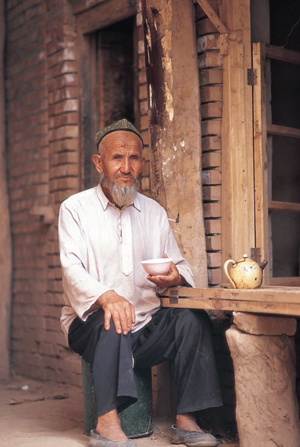

A Uighur man sits in the shade with his teapot and bowl of tea, in Kashgar, in western Xinjiang.

The Kazakhs who live in the northern part of Xinjiang make a simple pulao that is full of flavor. We call for 3 tablespoons fat or oil—festive pulaos are made with more fat, but this is a plain, almost everyday pulao, hence the restraint. (If you feel you must, you can reduce the quantity even further, to 2 tablespoons.)

We have really come to appreciate goat meat in the last few years for its clean lamb taste and reasonable price. If you can’t find goat, use lamb instead, as directed below. Have your butcher chop the meat into 2-inch chunks. Accompany the pulao with a simple chopped salad such as Cucumbers in Black Rice Vinegar (page 83).

2 cups medium-grain Mediterranean rice, such as arborio, baldo, or Valencia

1½ pounds goat shank or lamb back ribs, trimmed of excess fat and cut into 2-inch chunks, or bone-in stewing lamb, cut into chunks

3 tablespoons rendered lamb fat (see Glossary) or vegetable oil (see headnote)

1 large onion, diced

3 large carrots, peeled and cut into julienne or coarsely grated (2 cups)

1½ teaspoons salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

3 cups hot water

Place the rice in a sieve and rinse three or four times with cold water. Set aside.

Rinse the meat with cold water. Pat dry. Set aside.

Place a wide heavy pot over medium heat. Add the fat or oil, and when it is hot, add the meat and brown, using a wooden spoon to turn it so all sides are exposed to the hot oil, for about 6 minutes. Add the onion and cook for 4 minutes, or until mostly translucent and starting to brown. Add the carrots and cook for 4 minutes. Add the salt and pepper and stir in.

Sprinkle on the rice and stir it in. Add the water, raise the heat, and bring to a boil. Cover the pot tightly (use aluminum foil if necessary to seal it well), reduce the heat to very low, and cook for 40 minutes. Remove from the heat and let stand for about 10 minutes to firm up.

Serve on a platter, the rice mounded in the center and the meat on top.

Serves 4 as a main course

Butter is consumed in great quantities in the Tibetan-populated areas beyond the Great Wall. It’s used in tea and in cooked dishes, as lamp oil and as an offering at the temple, and also, in wintertime, as a way of protecting the skin and hair against the cold. Here in the market in Lhasa, near the Jokhang Temple, butter is displayed for sale alongside boxes of incense and some prayer flags.

Late May. The rain was coming in sheets straight at us, blown by a fierce north wind. We were in the grasslands south of Labrang, in Gansu, riding sure-footed Tibetan ponies, with miles still to go before we got back to town. A small, low house appeared, barely visible, about a hundred feet off the track we were following. We decided to seek shelter until the worst of the storm had passed, so we rode up, sending the two dogs chained outside into a frenzy of barking. The woman of the house appeared and gestured to us to tie up the horses and come inside.

She led us through the outer room, where stacks of brush and dried yak dung (for fuel) were stored, and into the house, shutting the door firmly behind us. The house was a single room, a long rectangle with a stove in the middle, a sleeping platform at one end with a stack of folded thick covers on it, two benches by the stove, and shelves on one wall for bowls and utensils. The roughly plastered walls were very thick, and the room was snug and warm, an oasis, a haven. I was shivering uncontrollably in great shudders as I sat down by the stove. It was narrow, with a stovepipe at one end and a top surface large enough to hold two kettles.

As her slender fourteen-year-old son sat staring at the unexpected visitors, and the wind whipped the rain about outside, our hostess got down four bowls from a shelf and set them on a ledge. From a wooden box, she dolloped a generous two or three tablespoons of butter into each bowl. Then she lifted one of the kettles off the stove and poured hot tea over the butter. The tea was a mix of brick tea (fermented coarse black tea) steeped with a little salt, with a little butter already in it. The woman handed me a bowl, curves hot to my numb hands, steam rising from the pale liquid.

I’m not a huge fan of butter tea; I can drink it, but it’s an effort. And I knew that soon the butter she had put in the bowl so generously would melt and make the tea even more difficult for me to get through, so I hurried to take a few scalding-hot sips before that happened. The tea was a little salty, with a cheesy aged-butter undertaste.

But she hadn’t finished: She brought out a wooden box and opened it. Inside was tsampa, roasted barley ground into very fine flour. She gestured to me to hold my bowl out toward her, then added some tsampa to my tea. I stirred it in with my fingertips, slowly moistening all the dry, powdery tsampa. The butter smoothed it beautifully, and soon I had a ball, like a stiff dough, but ready to eat. Holding the warm tsampa ball in my left hand, I broke off small bite-sized pieces and slowly ate my fill. And it was filling.

As I warmed up, I felt so grateful, not only for the hospitality, but also (in the self-absorbed way of the traveler) because the butter tea had been transformed into food that I could eat with pleasure. As I looked around the spare low-ceilinged room, I was brought back to basics. All that was needed for life was in that space: simple food, fuel, and fire, and human warmth and welcome.

A while later, during a lull in the storm, we headed back out into the rain, ready for the rest of our journey. N

We’ve seen fields of barley growing all over Tibetan-inhabited landscapes, from Burang, in western Tibet, to the valleys of Gansu province. We can’t tell one kind of barley from another, but we’ve been told that Tibetans grow several varieties. Barley is their staple grain, for it can survive the short growing season, cold winters, and relatively dry summers of Tibet. Only in a few lower-elevation valleys in eastern Tibet can wheat be grown successfully.

We don’t know when it was first made, but tsampa (sometimes written tsamba, or, in the modern Chinese Pinyin transcription, as zamba), the traditional Tibetan mainstay, is a very inventive and adaptable food. Whole barley grains are roasted (often in hot sand) and then ground to a fine powder, as fine as flour. Raw flour, like raw grain, is not edible, but because tsampa is made from cooked grain, it needs no further cooking. (We’ve learned that other crops, including some legumes, are sometimes used the same way as barley to make a form of tsampa: they’re roasted until they’re cooked through, then ground into a fine flour-like powder.)

Tsampa has a wonderful toasted grain aroma and flavor. Tibetans traditionally eat it dissolved in hot tea. The tea moistens it completely. And since Tibetan tea is made with butter and salt, the dissolved tsampa becomes like a kind of instant bread.

Because tsampa is lightweight, it’s a very portable food. Tibetan nomads and travelers usually carry only a cloth sack of tsampa, some tea, salt, and butter as their provisions; wherever they find themselves, they can boil water and make tea and tsampa. The combination has enabled Tibetans to survive in an extreme landscape for centuries (see “Tsampa in a Storm,” page 179).

In parts of Tibet where there are more food choices, of course, in towns and lower-elevation valleys, people have more varied diets. But tsampa is still an important food, and it also finds its way into other dishes (see Tsampa Soup, page 47). We’ve come to love having a good supply of it on hand. We eat it for breakfast, stirring its warm toasted grain flavor into yogurt (see Morning Tsampa, opposite), and also enjoy the smoothness and depth it gives when used to thicken soups or stews.

If you happen to live near a Tibetan Buddhist monastery or community, you may be able to buy tsampa ready-made, but most of you will be, like us, obliged to buy barley berries (whole grains), and dry-roast and grind them for yourselves at home. Here’s what we suggest: Buy a pound of barley berries, preferably organic. Start by roasting 2 cups berries, as directed below, which will yield about 3¾ cups tsampa. You’ll find out how the process works, and then you’ll be able to see if you want to make larger batches or just make it in 2-cup lots, as we do.

2 cups barley berries (whole grains), preferably organic

Place the barley berries in an 11- to 12-inch heavy skillet (cast iron works very well) and dry-roast over medium-high heat: Stir constantly with a flat-ended spatula or wooden spoon, moving the grains off the hot bottom surface and rotating them from the center to the outside, to ensure an even roast with no scorching. The grains will crackle a little as they expand in the heat, will start to give off a toasted grain aroma, and will change color. Keep on stirring and turning until all the grains have darkened to more than golden, about 10 to 14 minutes. Test for doneness by trying to bite into one of the grains—it should yield easily (times will vary depending on the amount you are roasting, the size of your pan, and the heat). Remove the pan from the heat and keep stirring for another minute or two to prevent scorching.

If you are using a coffee or spice grinder to grind the grain, you will need to work in batches. (A flour mill works well if you have one: no need for small batches, and your grind will be finer and more even.) Transfer about ½ cup of the toasted grains to a clean, dry coffee or spice grinder and grind to a fine flour-like texture (you will hear the sound change as the granules get reduced to a powdery texture). Turn out into a bowl and repeat until all the grain has been ground to flour. If you want to perfect your grind, pass the milled powder through a fine sieve and then regrind any remaining larger pieces.

Let cool completely, then store in a well-sealed wooden or glass container in a cool place. We’ve found tsampa keeps indefinitely in the refrigerator.

Makes about 3¾ cups

ROASTED BARLEY FLOUR: We experimented with barley flour too, wanting to see whether we could use it as a substitute for tsampa by roasting it in a skillet. We found that the roasted flour had a completely different texture from tsampa, though a similar taste. With tsampa, because the whole grains are cooked first, when they are ground into flour, each fleck of flour is very soft. When we roasted barley flour in a hot skillet, it became gritty, as each separate fleck of flour toasted and dried out. We were forced to conclude that there is no quick answer to making tsampa. However, the roasted flour is an adequate substitute for tsampa in cooked dishes where it is used as a thickener, as, for example, in Tsampa Soup (page 47) or Stir-Fried Stem Lettuce Lhasa-Style (page 103).

With a generous supply of tsampa in the pantry, all sorts of treats become easily available. We like tsampa stirred into good whole-milk yogurt, for the taste of the roasted grain is wonderfully welcoming with the yogurt’s lush smoothness. Start with your favorite yogurt, and add fruit if you’d like. Sweeten it with a little honey or sugar or maple syrup if you wish. Eat with pleasure for breakfast, or anytime.

About ½ cup whole-milk yogurt, plain or sweetened

3 tablespoons Tsampa (opposite), or to taste

A handful of berries or chopped fruit (optional)

Honey, sugar, or maple syrup to taste (optional)

Place the yogurt in a bowl and stir in the tsampa thoroughly so it’s all moistened. Add fruit and a sweetener if you wish.

Serves 1

Jars of yogurt and stacks of local flatbreads, in the Tibetan quarter of Lhasa.

Long before we met Miao people in China, we’d spent time in Hmong communities in Thailand and Laos. (There they call themselves Hmong; in Southeast Asia the name Miao has pejorative roots, but in present-day China, people refer to themselves as Miao, at least to outsiders, so we’ll use both terms here.) We’d read a remarkable ethnography written in 1976 by W. R. Geddes, called Migrants of the Mountains, about the traditional lifestyle of the Hmong, and we’d also seen a moving piece of documentary film about the Hmong coming as refugees to the States after the Vietnam War, The Best Place to Live (by anthropologist Louisa Schein). A large number of Hmong from Laos fought as U.S. allies in the Vietnam War. Afterward, many Hmong from Laos fled to refugee camps in Thailand; several thousand of them were eventually resettled in the United States.

We were aware that the traditional Miao/Hmong homeland was in China. We’d read that there were as many as four million Miao living in China, but it was very hard to imagine the population on that scale, for in Southeast Asia they live as slash-and-burn agriculturalists in very remote areas, in communities of less than three hundred people.

Now, twenty years later, we’ve had a chance to visit many Miao communities in China, and we have a much better sense of where and how they live. But still for us they remain a remarkable people. Like the Yao, another non-Han population, closely linked linguistically to the Miao, they are widely dispersed through southern and southwestern China, as well as through mainland Southeast Asia. More than half of the population of Miao living in China live in the very poor mountainous province of Guizhou, but large numbers also live in Hebei, Sichuan, Yunnan, Hunan, and Guangxi provinces. We’ve even seen Miao women selling vegetable seeds and herbs on a sidewalk in Lhasa, in Tibet, a thousand miles from where we would expect to see them.

The Miao have an incredibly rich textile tradition, especially for embroidery and appliqué and batik, as well as for indigo-dyeing. All Miao women traditionally embroider: baby carriers, hats for babies, aprons, and jackets that are part of the traditional dress. Within the Miao grouping, there are many subcategories (some say more than eighty), mostly based on distinctive elements in their traditional dress. Each group can be distinguished, by those who know, by the details of the embroidery and the design of the jewelry.

Like other non-Han people who lived in the remote valleys and mountains in southern China, the Miao were historically thought by the Han to be uncouth barbarians. They are still fundamentally disdained and viewed as uncultured by many outsiders, but now, ironically, they also have a curiosity value as “exotic” in the new China. Tourists come from other parts of China (and from Japan, Taiwan, and Western countries) to marvel at their traditional festivals, their traditional clothing, their distinctiveness.

Nowadays, most Miao are settled farmers, tilling the terraced landscapes around their villages; growing rice and corn, vegetables, tea, rapeseed (for oil), and more; and raising pigs.

Miao (Hmong) men in traditional indigo-dyed clothing play the lusheng, a bagpipe-sounding instrument like a large panpipe, at a ceremony in the village of Lande, in Guizhou.

This woman’s distinctively shaped headdress indicates she is Ge, a subset of the Miao (Hmong) that is not recognized as a separate “minority people” by the Beijing government. The Ge people live in the area around the town of Chong’an, where this photograph was taken, as do many Miao.