On the banks of the Mekong River, just outside Jinghong, in southern Yunnan, a man waters beds of green vegetables. Each year in October, as the water level in the river drops at the end of the rainy season, people who live along the river, from Yunnan to Thailand, cultivate freshly exposed areas along its banks for planting garlic and scallions and green vegetables.

Though it’s rare to be served raw food in central China, except the occasional wedge of cucumber, in the areas beyond the Great Wall there are plenty of crisp raw vegetables and herbs.

Salad traditions in these cultures and regions vary enormously. In the mild subtropical climate areas of Yunnan and Guizhou, salads are intensely flavored, tending to the tart and chile-hot (see Green Papaya Salad with Chiles, page 78, and Pea Tendril Salad, page 66). Sprouts, dried kelp, and the dried fungus known as tree ears all find a place in salads: see Hani Soy Sprout Salad (page 73), and Cucumber–Tree Ear Salad (page 79). Up north on Inner Mongolia’s border with Russia there’s a salat tradition that seems like fusion food: Napa and Red Onion Salad (page 86) and Beef-Sauced Hot Lettuce Salad (page 67) are delicious examples. Farther west, along the border with Siberia, lies the Kazakh area of northern Xinjiang, where there are similar salads (see Sprouts and Cabbage Salad Kazakh-Style, page 72). In Tibet, where greenery and fresh vegetables have not traditionally been available (though they are now being grown in greenhouses near many towns), salads don’t have much meaning. Freshness comes from condiments and pickles (see the Condiments and Seasonings chapter).

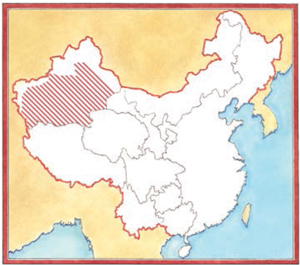

In the oases of Xinjiang, where tomatoes, peppers, melons, cucumbers, and greens grow in abundance in the desert heat, chopped or sliced tomatoes and cucumbers are the basis for many simple refreshing assembled salads that are similar to those across the border in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Along with a generous sprinkling of salt, salads here are flavored with fresh herbs such as coriander or dill, and scallion greens, and/or pomegranate seeds in season (see Cooling Oasis Salad with Tomatoes and Herbs, page 89). Vinegar is on the table as a condiment for cooked dishes, not for dressing these salads.

Curiously, in China the words “raw” and “cooked” carry other meanings. They have long been used to distinguish between different groups of non-Han people. “Cooked” refers to people considered somewhat civilized in Chinese terms—i.e., people who are more sinicized—while “raw” refers to people and cultures viewed as very uncivilized.

Tree ears: on the left, dried tree ears; on the right, soaked, and thus ready to be cooked and eaten.

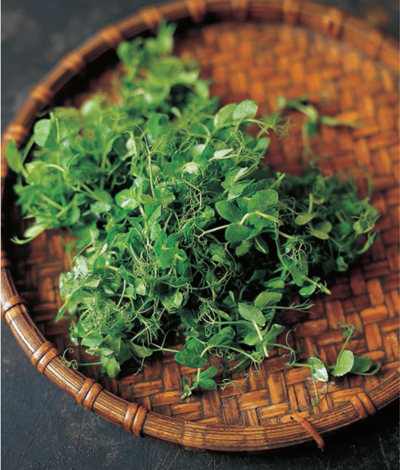

Pea tendrils, also known as pea shoots or pea sprouts, are the top 6 to 12 inches of the growing tips of green pea plants. We love pea tendrils, and we’re happy to see them appearing fresh in more and more markets each year. There are two kinds: a finer version, where the shoots are very young and tender, with a delicate texture, and a more vigorous version, which is what we call for here, with twining stems, developed small leaves, and sometimes white pea flowers.

This attractive warm salad comes from the Dai people in southern Yunnan province. As in many Dai dishes, flavors combine tart-sour (the sesame oil–vinegar dressing) with chile heat (the garnish of slivered red cayenne chile) and mild sweetness (the pea tendrils) in a nice balance. [PHOTOGRAPH ON PAGE 308]

1 pound pea tendrils (see headnote)

DRESSING

2 tablespoons rice vinegar

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon roasted sesame oil

1 small red cayenne chile or ½ large

2 tablespoons peanut oil or vegetable oil

½ cup thinly sliced shallots

Wash the pea tendrils well; drain and set aside.

Place the vinegar, the 1 teaspoon salt, and the sesame oil in a small cup and stir well; set aside.

Strip out and discard the seeds from the red chile, then thinly slice it. Set aside.

In a large pot, bring 3 quarts salted water to a boil. Toss in the pea tendrils and stir to immerse them in the water. Cook for 3 minutes, or until just tender to the bite—because pea tendrils vary considerably in terms of toughness, the cooking time may vary a little. Drain thoroughly in a colander and refresh briefly under cold water, then drain and press out excess water. Turn the greens out onto a cutting board and pull together into a mound. Chop with a chef’s knife or cleaver into about 1-inch lengths, so that they will be easier to eat. Press out the excess liquid again.

Place the tendrils on a wide serving plate. Stir the sesame oil dressing again, pour it over the tendrils, and toss gently to coat.

Place a wok or heavy skillet over high heat. When it is hot, add the oil and swirl gently, then add the sliced shallots, lower the heat to medium-high, and fry until the shallots are pale to medium brown, about 2 minutes. Use long chopsticks or a spatula to keep the shallots moving so that they don’t burn. Take the pan off the heat and pour the oil and shallots over the pea tendrils.

Sprinkle on the sliced red chile and serve.

Serves 4 as a salad or side dish

Pea tendrils, the tender finer version.

Beef-Sauced Hot Lettuce Salad

We came across this warm salad in Inner Mongolia, a place where Siberian and Mongolian worlds meet and are cross-blended with the traditions of the people who have moved into the region from many other parts of China. We don’t know if this is a fusion dish of some kind, perhaps showing a Russian influence, but we do know that it’s unusual and very appealing. Torn romaine is tossed in a hot dressing flavored with ground beef and warm seasonings. The crunch of the barely wilted lettuce is a beautiful contrast to the full-flavored warmth of the vinegar-spiked sauce.

About 4 packed cups coarsely torn romaine lettuce (see Note)

DRESSING

1 tablespoon peanut oil or vegetable oil

1 tablespoon minced garlic

1 tablespoon minced ginger

½ pound (1 packed cup) ground beef

½ teaspoon salt, or to taste

1 tablespoon soy sauce, or to taste

1 tablespoon Jinjiang (black rice) vinegar, or to taste

½ cup warm water

2 teaspoons cornstarch

1 tablespoon cold water

½ teaspoon roasted sesame oil

Place the lettuce in a wide salad bowl or serving dish and set aside.

Place a wok or heavy skillet over medium-high heat. When it is hot, add the oil and swirl to coat the bottom of the pan. Toss in the garlic and stir-fry for 10 seconds, then add the ginger. Stir-fry over medium-high to medium heat until slightly softened and starting to turn color. Add the meat and use your spatula to break it up so there are no lumps at all, then add the salt and stir-fry until most of the meat has changed color. Add the soy sauce and vinegar and stir to blend. Add the warm water and stir. (The dressing can be prepared ahead to this point and set aside for up to 20 minutes. When you are ready to proceed, bring to a boil.)

While the dressing mixture is coming to a boil, place the cornstarch in a small cup or bowl and stir in the cold water to make a smooth paste. Once the liquid is bubbling in the pan, give the cornstarch mixture a final stir, add to the pan, and stir for about 1 minute; the liquid will thicken and become smoother. Taste for salt, and add a little salt or soy sauce if you wish. Add the sesame oil and stir once, then pour onto the lettuce. Immediately toss the salad to expose all the greens to the hot dressing. Serve immediately (or see Note).

Serves 4 as a salad or side dish

NOTE ON TEXTURE: If you use romaine lettuce, the salad will have good crunch as well as some wilted softer textures when you first serve it. We love the contrast. If you prefer a softer texture, either let the salad stand for 5 minutes before serving it, to give the greens more time to soften in the warm dressing, or use leaf lettuce instead of romaine.

It poured nearly every day of my first visit to Sipsongpanna, the southernmost area of Yunnan. I took a plane from Kunming south to a town called Simao, and from there it was a day’s bus ride on winding mountain roads to reach the town of Jinghong. I was thrilled to get there and to have my first glimpse of the Mekong River, flowing south out of China and into Southeast Asia, connecting two worlds.

In Sipsongpanna, I felt as if I was no longer in China. Some women wore sarongs instead of cotton jackets and pants in dull colors. They were Dai women (see page 237), distinctive and graceful. Other women were in short tunics of handwoven hemp, their legs bare, and their men were in loose hemp trousers, very like tribal people I had seen in northern Burma some years earlier. Many of the streets were unpaved, slick with mud in the September rain, and my flip-flops made a muddy spatter on the back of my legs as I walked.

There was a regular boat service from Jinghong to villages downstream, so one day I took the boat to the village of Menghan, sharing the boat with an assortment of people, everyone loaded with produce and equipment, with chickens in bamboo cages, and lots of children. We made several stops at small landings along the way. The boat waited for an hour in Menghan, unloading and taking on new passengers and cargo, so there was a little time to wander around and explore. The houses in the village were made of wood, graceful large structures built on stilts. Colors were brilliant in the overcast light, and whenever it stopped raining, the green of rice paddies glowed in the distance.

Too soon, it seemed, we were heading slowly back upstream, the boat engines working hard against the flow of the monsoon-swollen river. I had no idea then that in twelve years I’d be back in Menghan, traveling with a family of my own (see Dai Spicy Grilled Tofu, page 111). N

At a street market in Menghan, in southern Yunnan, a Dai woman wearing a traditional sarong and blouse trims sugarcane; others sit waiting with their bags of produce.

The tall blue-eyed woman staying in the dormitory of the Kunming Hotel caught my eye. She wore lots of chunky silver rings set with Tibetan turquoise. She was over sixty years old, I thought, very unusual in a dorm full of twentysomethings, but she had a vigor to her that was younger than her age. I asked her where she was from, and how long she was staying in Kunming.

“From Switzerland,” she replied. “I’m taking the overnight train tomorrow to Chengdu, then I fly straight to Tibet.”

I had a ticket on the same train to Chengdu, so we shared a taxi to the station the next day. The station was crowded, and as we stood in an echoing noisy tunnel under the tracks, waiting in a crowd to board the train, we almost had to shout to each other to be heard.

“Do you know the book Forbidden Journey?” she asked me.

“A wonderful book! I’ve always wondered what became of her, the author,” I said.

“Well,” she said with a smile, “I’m Ella Maillart. It’s my book.”

I was stunned. I’d read many of her books, extraordinary books. She had lived as a student in Moscow in 1932 and then traveled through Soviet Central Asia, experiences she describes in her first book, Turkestan Solo. In 1934, she went to Beijing, and from there she made an epic six-month journey on foot and horseback west across China all the way to Hunza (in present-day Pakistan), a trip she describes in Forbidden Journey. Her books are classics, travel literature about a kind of travel that is unimaginable now in the age of e-mail, cell phones, and rapid airplane connections.

On the train, we spent much of the twenty-three-hour ride talking. Ella told me about driving overland from Switzerland to India in 1938 with a friend who was a morphine addict; about spending the war years in India; and about her long friendship with Nehru, India’s prime minister from independence, in 1947, until 1964.

“I haven’t talked about these things in years!” she said. “This will be my first time to Tibet,” she went on. “I didn’t get there in the thirties, and then for many years, because of the Chinese invasion of Tibet, I thought that it would be wrong to go, but now I’m getting old [she was in fact eighty-two when we met] and I might never have another chance.”

“I’m also headed to Tibet,” I told her, “but by bus, from Golmud.”

“Then hopefully I’ll see you again.”

Two weeks later, I got to Lhasa and found Ella at the Snowland Hotel. She was packing. It was her last night in Lhasa. We went out for supper at a nearby eatery. Ella was a vegetarian, so we shared plates of stir-fried cabbage, stir-fried bean sprouts with slivered scallions, boiled potatoes with coarse salt, and a plate of chile-hot tree fungus.

“Why didn’t you ever marry?” I asked Ella as we ate.

“I never found a man who was interested in the same questions I was,” she replied, her blue eyes gazing straight at me.

“I’ve decided not to return to my job,” I followed, perhaps looking for advice, looking for approval.

“‘Il faut suivre ta boussole’ [You must follow your compass], as we say in French. Do what feels right to you, then figure out how to earn a living at the same time.”

We finished eating and exchanged addresses, and the next morning she was gone. N

A Tibetan nomad walks on the vast plain below Mount Gurla Mandata, in the Mount Kailas area of western Tibet. The plain is at an elevation of about 15,000 feet.

Long ago, Bahargul, a Uighur woman who had come to Toronto to complete her master’s degree and was a friend of a friend, taught us how to make Uighur pulao. We included that pulao in Seductions of Rice. When the pulao was done, Bahargul quickly chopped up a salad just like this, to eat alongside as a cooling accompaniment to the flavored rice and meat. We love it still.

1 medium-large bell pepper, preferably yellow or orange

1 large or 2 medium ripe tomatoes

½ teaspoon salt, or to taste

About ¼ cup chopped coriander, mint, or dill

Remove the core, seeds, and ribs from the pepper. Slice lengthwise in ¼-inch-wide strips and cut the strips into 1-inch lengths. Place in a shallow bowl. Chop the tomato into small chunks and add to the bowl.

Sprinkle on the salt, add the herbs, toss gently, and serve.

Serves 4 as a small salad

YOGURT DRESSING: You can add a yogurt dressing to the salad if you like. Whisk 2 tablespoons well-chilled full- or reduced-fat yogurt with ½ teaspoon salt and a pinch of cayenne, then pour over the salad. Toss gently to mix well, sprinkle on a little chopped coriander, mint, or dill, and serve immediately.

In the mountains of northern Xinjiang, I spent a night sleeping alongside six other men in a Kazakh yurt, one of several dozen yurts set up together near Kanas Lake. The yurts functioned like guesthouses for Kazakh workers in the region, and the cost of a night’s sleep included breakfast. For breakfast that morning we had steamed breads, this simple bean sprout and cabbage salad, and hot tea. We ate at a small table outside, surrounded by snow-capped mountains. All around us was activity, people riding horses, shoeing horses, packing packs. (Many of the Kazakh men make money leading Han Chinese tourists on horseback treks, sometimes several days in length.)

2 cups shredded or coarsely grated Napa cabbage

1 cup bean sprouts

3 red cayenne chiles, seeded and minced

2 tablespoons rice vinegar

1 teaspoon salt, or to taste

Place the cabbage and bean sprouts in a large bowl. Pour boiling water over to cover, and let stand for 3 to 5 minutes. Drain and place in a salad bowl.

Add the chiles to the cabbage and sprouts and toss.

Whisk together the vinegar and salt and pour over the salad. Toss to blend, taste for salt, and serve.

Serves 4 to 5 as a salad or side dish

My favorite parts of the Hani markets in southeastern Yunnan (see page 316) were the long aisles piled high with sprouts. There were chickpea sprouts, soybean sprouts, mung bean sprouts, and several others I couldn’t identify. They were in giant piles, in beautiful shades of white, brown, and yellow, all bursting with freshness.

This salad is like one I ate at Luchen market. It makes a bright-tasting side dish.

SALAD

1 pound soybean sprouts (see Note)

2 tablespoons soy sauce

1 teaspoon finely chopped seeded red cayenne chile

2 tablespoons minced scallions (white and tender green parts)

¼ cup coriander leaves

DRESSING

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

1 tablespoon rice vinegar

½ teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon roasted sesame oil

Wash the soybean sprouts and drain them. Bring 8 cups of water to a boil in a medium saucepan. Add the sprouts and soy sauce and bring back to a boil. Reduce the heat to a simmer and let the sprouts cook, uncovered, for 1 hour, or until tender.

Drain the sprouts in a colander (if you like, drain them over a bowl and save the cooking water for a vegetarian broth), and put them in a shallow bowl or on a plate.

Place the dressing ingredients in a cup and use a fork or small whisk to blend them together well. Pour the dressing over the sprouts and toss gently to mix. Add the red chile, scallions, and coriander leaves and gently toss again. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Serves 4 as a salad or side dish

NOTE ON SOYBEAN SPROUTS: Unlike the more commonly available mung bean sprouts, soy sprouts, which have larger green or yellow half-beans attached to them, can take long cooking without turning to mush. Look for them in Chinese grocery stores and specialty produce markets.

In the Yi and Hani markets of southeastern Yunnan there are piles of bean sprouts of many kinds for sale; these soy sprouts are in the market in Luchen.

In the small city of Kaili in eastern Guizhou, there’s a lane of street vendors who set up around sunset. During the day, the same lane is a small produce and fish market, but down another lane to one side, by some steps, there are stalls that offer a street version of hot pot: You choose skewers of fish or squid or vegetable or tofu, and they are then immersed in a vat of hot broth to cook or reheat before being handed to you. At the bottom of the steps, there’s a woman selling what I called in my diary “sticky rice sandwiches,” a Miao specialty, we’ve since learned. The “bread” is two small disks of sticky rice, each the diameter of a small hamburger bun. Pressed between the disks is a dollop of minced dressed firm tofu very like Pressed Tofu with Scallions and Ginger (opposite). The sandwiches cost about fifteen cents, and they’re delicious, with a tender texture.

Tofu portraits: on the left, two pieces of pressed tofu lie on top of a block of fresh tofu, the firm Chinese version. On the right, pieces of frozen tofu: the cube in the front has been thawed, the water squeezed out, and the tofu torn in half to show its sponge-like open structure, ideal for absorbing flavor.

We think of ourselves as unofficial promoters of certain foods, and pressed tofu is one of them. We’ll often take a pressed tofu dish, such as this one from the Dai people in southern Yunnan, to a potluck supper so that friends who haven’t tasted it can have a chance to try it. At one such potluck, I happened to be standing by the buffet table when an eight-year-old boy came up with his father.

“What’s that?” he asked his father.

“I think it’s tofu,” his father replied.

The boy crinkled his nose and looked unimpressed. His father served himself and took a bite, and then another bite, and then his son decided to try it. Then he too took another bite. The rest of the evening, every once in a while, I’d notice the boy pop over to the table and take a little more pressed tofu. Success!

Pressed tofu is now available in most East Asian groceries. It comes in white, pale brown, and dark brown, depending upon whether or not it has been flavored with soy and other seasonings, and it is always inexpensive. It is extremely versatile: it can be grilled, stir-fried, or simmered. It has the consistency of a firm-soft cheese (such as unripe camembert) but no cheese flavor, just a mildly salty subtle taste of bean.

This particular dish is a cross between a chopped salad and an appetizer. It has chile heat, like so many Dai dishes, and it is traditionally served with small wedges or sections of cabbage that diners can use to scoop up mouthfuls of salad. Serve with sticky rice if you wish.

⅓ pound pressed tofu

½ cup lightly packed chopped scallions (white and tender green parts)

1 tablespoon soy sauce

1 tablespoon water

½ teaspoon crushed dried red chile or chile pepper flakes

2 tablespoons minced ginger

ACCOMPANIMENTS

6 to 8 small cabbage wedges (green or savoy cabbage) or wedges of iceberg or other head lettuce or about 12 leaf or Bibb lettuce leaves

1 lime, cut into small wedges

Rinse the pressed tofu, then cut it into very small pieces ¼-inch or smaller cubes) and place in a medium bowl. Add the scallions to the tofu, and set aside.

In a small bowl, stir together the soy sauce, water, and dried red chile. Let stand for 5 minutes to allow the flavors to blend.

Add the ginger to the tofu and scallions and toss to mix well. Pour the dressing over. Serve with the cabbage or lettuce leaves, and invite your guests to squeeze on a little lime juice as they eat, mouthful by mouthful.

Serves 4 to 6 as a salad or appetizer

In early October 1985, I arrived in Golmud on the slow train overnight from Xining. Golmud lies in what looks like the middle of nowhere on a map, in a featureless dry plateau in the province of Qinghai, not far from the edge of the Takla Makan Desert. Camels roam outside town, the wind blows, and in fall and winter, straggles of Tibetan nomads pass through, headed to Lhasa on pilgrimage.

Golmud was for a long time a transportation hub of a kind, for until recently the railway from Beijing and central China ended there (see Note). Anyone who wanted to go farther, say south to Lhasa, or northwest to Dunhuang, had to find space in a truck or a bus (in earlier times they’d have searched out a horse or a camel).

When I got to the bus stand, several families of nomads (pilgrims headed to Lhasa) sat waiting, leaning against a mud-brick wall for shelter from the wind and the dust it brought. I asked around, but no one knew when or even if a bus might leave that day. So I set my pack down and joined the pilgrims by the wall. Eventually a man came and opened the door of one of the two rackety-looking buses parked in the lot. Luggage was tied on the roof with ropes, tickets sold, and then we headed out across the flat, bare landscape.

It was an amazing trip, that journey with the pilgrims. Many of them spent the whole time praying, saying prayers rapidly under their breath and sliding their prayer beads between thumb and forefinger. There were lots of older men and women, each with a small prayer wheel, which they kept spinning as we drove along. There were several women with babies and small children, their hair in many long gleaming braids down their back, all joined at the bottom and threaded with turquoise beads in the Amdo (northeast-Tibetan) style. Most people had brought food for the journey, so every once in a while, someone would offer around pieces of dried yak or goat meat; then we’d all chew slowly, making it last. All I had to share were some rather tasteless hard candies, but they too were a welcome break.

Despite its apparent barrenness, the landscape had life in it. Every so often a few of the men would get very animated and point out the window. Sometimes I could eventually make out what they had spotted long before—a herd of wild asses, a fox, a wild yak—but most often I couldn’t see the animals at all.

Late on the afternoon of the second day, we started heading up the Kyichu River Valley to Lhasa. Everyone was keyed up and expectant. The hum of prayer in the bus grew louder. When the Potala Palace at last came into sight, high on its hill, all gleaming roofs and fantastical, the bus came alive with chanting, prayers, and joy. N

NOTE: Since July 2006, the railway has been opened all the way to Lhasa, to the dismay of Tibetans, who feel it will encourage an influx of settlers from central China (see “Lhasa Tensions,” page 205).

A Tibetan woman, her hands clasped behind her back, keeps her prayer beads moving while she prays.

It’s no wonder that green papaya recipes pop up frequently throughout Asia, because almost anywhere papaya trees grow, they grow easily and produce abundantly. Green papaya is eaten as a vegetable from India to Thailand, Yunnan, and Vietnam. And green papayas are easy to transport, not nearly as fragile as ripe ones, making them inexpensive in the market.

This dish comes from a tiny no-name restaurant on a back lane in Jinghong, in the far south of Yunnan province. At the restaurant, it came with almost every meal, like an appetizer or a palate refresher. The salad is lightly pickled, but the green papaya remains slightly crunchy. It reminds us a little of the lightly pickled carrots and white radish that come as side condiments in Vietnam.

When we make the dish, we julienne the green papaya as people do in Thailand and Laos for som tam (pounded green papaya salad). We peel off the dark green skin, then use a cleaver to chop and slice the papaya, as described below. The process may sound complicated, but it’s not. It’s easy and fun, especially if your cleaver (or chef’s knife) is sharp.

Make the salad a couple of hours, or as long as 6 hours, before you wish to serve it.

One 2-pound green papaya

2 tablespoons ginger, cut into small matchsticks

1 to 2 tablespoons thinly sliced seeded red cayenne chile

FOR PICKLING

4 cups water

½ cup rice vinegar

1 tablespoon salt

1 teaspoon sugar

Peel the papaya using a vegetable peeler, and cut off the hard stem end. Rinse the papaya to make it easier to hold on to. Hold the papaya in one hand, and use a sharp cleaver or chef’s knife to make repeated lengthwise shallow cuts straight into the surface of the papaya, making many, many parallel cuts. When you have covered the first side of the papaya with lengthwise cuts, stand the papaya on end on a cutting board and then shave off the julienned strips of papaya by sliding your cleaver down the cut side of the papaya (in the same way you slice kernels off a cob of corn), trimming off all the long narrow slivers.

Repeat on the other side of the papaya, then continue until you have cut most of the papaya into julienned strips. (Be sure not to cut too far down into the center of the fruit, because you don’t want any papaya seeds mixed in with your shreds. Papaya seeds have an incredibly strong taste that is not what you want in your dish!) You should have 4 cups.

Put the shredded papaya in a bowl, add the ginger and red chile, and mix well.

In a nonreactive saucepan, bring the water to a boil. Add the rice vinegar, salt, and sugar, stirring to make sure the salt and sugar dissolve. Bring back to a boil, then pour the brine over the papaya. Let sit for 1½ to 2 hours.

Drain the salad just before serving. Put it out in a bowl so guests can help themselves, or serve individually in small condiment bowls.

Serves 4 to 6 as a condiment/salad

PRESERVED VEGETABLE OPTION: You can also add up to ½ cup finely chopped preserved green vegetable, such as pickled mustard greens (see Glossary), to the salad.

This Dong salad is made with crisp chopped cucumber and small pieces of well-soaked tree ear fungus, which are a beautiful shiny black against the cucumber’s pale green. They are dressed with warm and sharp flavors (ginger, vinegar, pickled chiles, sesame oil), and the salad tastes mildly pickled, a flavor characteristic of Dong cuisine (see page 120). Serve as a foil for hearty main dishes.

If you don’t have any pickled chiles handy, you can substitute a sliced fresh red cayenne chile, as described below. Start making the salad 45 minutes to an hour before you wish to serve it.

¼ cup dried tree ears (see Glossary)

About 2 tablespoons ginger, cut into fine matchsticks

1 tablespoon thinly sliced Pickled Red Chiles (page 34) or store-bought pickled chiles, or substitute 1 small red cayenne chile, seeded and very thinly sliced

2 tablespoons rice vinegar

1 tablespoon water

½ teaspoon salt, or to taste

1 medium English cucumber (about ½ pound)

1 teaspoon roasted sesame oil

Soak the tree ears in boiling water to cover for 20 minutes.

Place the ginger in a small bowl. If using a fresh chile, add it to the ginger.

Heat the vinegar and water together in a small nonreactive pan over medium heat, and stir in ½ teaspoon salt to dissolve it. When the mixture comes to the boil, pour over the ginger. Let stand for 10 to 15 minutes.

Drain the softened tree ears and chop into small pieces (nickel-to quarter-sized), discarding any tough sections. You will have about ¾ cup. Place in a medium bowl and set aside.

Peel the cucumber and cut lengthwise in half. Chop into irregular chunks no more than ½ inch by ¾ inch. Add them to the bowl with the tree ears. If using pickled chiles, add them to the bowl.

Pour the vinegar-ginger mixture over the cucumber mixture. Toss to mix well. Add the sesame oil and toss again. Let the salad marinate in its own juices for 30 minutes, giving it a stir several times to distribute the flavors.

Just before serving, stir the salad again, then taste and add a little salt if you wish.

Serves 4 as a salad or side dish

At a bus stop in southern Yunnan two Dai women on cell phones supervise a streetside grill.

In the early morning, a Dai noodle soup vendor sets up at the market in Menghan, in southern Yunnan. Morning market noodles, usually fresh rice noodles bathed in broth, are sold at small stalls like this one in all the local Dai markets. Customers sit on small benches at the table, help themselves to condiments, and get a warming start to the day.

I was so surprised to find dried kombu seaweed in mountainous landlocked Yunnan province. I saw it not only in “cosmopolitan” Jinghong, but also in the remote mountain town of Yuanyang. In China, kombu is called hai dai. You can generally find it here in North America in East Asian supermarkets, as well as in natural food groceries, sometimes labeled kelp, other times kombu, its Japanese name (see Glossary).

Once soaked, kombu has a great texture, a firm chewy bite that melts into tenderness. It’s sold in rectangular sheets about 8 inches by 4 inches or in long fronds that are folded. If the long sheets are what you have, unfold them and figure out what will give you the square inches called for in the recipe.

We’ve adapted this appetizer/salad a bit from the one I first tasted in Jinghong market. We use a thick soy sauce, a store-bought sauce that we have enjoyed for years at home; a brand from Taiwan called Kimlan, it has a distinctive orange label (see Glossary for more). Here in Toronto it is widely available in Chinese groceries. Don’t try substituting other “thick soys”—their taste is entirely different. If you can’t find Kimlan, substitute a regular soy sauce.

Serve this as a salad or as an appetizer with drinks.

2 sheets (each about 6 by 9 inches) kombu

About 2 tablespoons thick soy sauce (see headnote)

1 large or 2 small scallions, cut lengthwise into ribbons and crosswise into 1-inch lengths

Rinse the kombu well, then soak the sheets in warm water to cover for 20 minutes, or until well softened.

Drain the kombu and remove and discard any hard bits. Cut lengthwise into 2-inch-wide panels, then stack them and cut them crosswise into ¼- to ½-inch strips. You should have about 1 cup packed kombu.

Place in a wide bowl, immediately add the soy sauce, and toss well. Sprinkle on the scallion ribbons and serve.

Serves 4 as a salad or appetizer

NOTE ON TIMING: Kombu/kelp has a slightly mucilaginous texture after it has been soaked, so it should be dressed right away after soaking, so the ribbons don’t start to stick to one another.

LHASA SEAWEED SALAD: It’s hard to be more landlocked than in Tibet. But dried kombu is lightweight and keeps well, so it has become a useful vegetable in Lhasa and other Tibetan towns. We’ve seen it there shredded into soups, and we’ve also had it as a kind of intensely flavored salad, dressed with chile paste and scallions. With its red and green and black, its chile heat, and its faint tang of the faraway ocean, it’s an attractive and delicious addition to a dinner table. Whisk together about 2 teaspoons Guizhou Chile Paste (page 35) or Bright Red Chile Paste (page 18) with ½ teaspoon roasted sesame oil and a scant ½ teaspoon salt. Pour the dressing over the soaked kombu as soon as it is sliced, as above, and toss well to coat, then sprinkle on the scallion ribbons and serve.

Cucumbers are one of the mainstays for people living in the oases of Xinjiang. They’re used as a cross between a salad and a condiment. This is one of the easiest ways we know to brighten a weeknight supper. It also complements deep-fried treats such as Cheese Momos (page 212) or Giant Jiaozi (page 210) beautifully.

1 English cucumber (about ½ pound)

About 2¼ teaspoons salt

2 tablespoons Jinjiang (black rice) vinegar

1 teaspoon roasted sesame oil

Peel the cucumber completely, or remove lengthwise strips of peel, leaving some of the cucumber unpeeled, to give the slices an attractive look. Slice lengthwise in half and then in half again. Use a knife or sharp spoon to clean out the seeds. Cut each piece lengthwise in half, then cut crosswise into ¼-inch slices.

Place the cucumber in a bowl. Add 2 teaspoons of the salt and let stand for 10 minutes, then transfer the cucumber to a sieve or colander and rinse thoroughly under cold water. Squeeze gently to remove excess water, and place in a shallow bowl.

Whisk the vinegar and sesame oil together and pour over the cucumbers. Toss to blend. Set aside until ready to serve (no longer than 30 minutes).

Just before serving, taste, and add about ¼ teaspoon salt, or to taste, if you wish.

Serves 4 as a salad or side dish

CUCUMBER-VINEGAR SAUCE: If you mince the cucumber, this becomes more like a condiment than a salad. It’s a standard item at noodle stalls in Xinjiang and Qinghai provinces. Serve it with noodle dishes and pulaos, putting it out in a bowl, with a spoon, so guests can help themselves.

Serves 6 to 8 as a condiment

Dai Carrot Salad

There is so much good cooking in the small city of Jinghong (see page 227) in southern Yunnan province that it would take a long time to feel well acquainted with all that is there. Restaurant-hopping in the warm tropical evenings of Jinghong is lots of fun, but even better are the morning and afternoon markets, where there is an incredible variety of prepared foods to choose from. This carrot salad is one such dish: colorful and full of flavor.

1 pound large carrots

About 2 tablespoons Pickled Red Chiles (page 34) or store-bought pickled chiles, cut into ½-inch slices

3 scallions, smashed and sliced into ½-inch lengths

1 tablespoon soy sauce

1 tablespoon rice vinegar

1 teaspoon roasted sesame oil

½ teaspoon salt, or to taste

2 to 3 tablespoons coriander leaves, coarsely chopped

Peel the carrots. Using a cleaver or chef’s knife, slice them very thin (⅛ inch thick if possible) on a 45-degree angle. You should have 3 cups.

In a medium saucepan, bring 4 cups of water to a boil. Toss in the carrot slices and stir to separate them. Cook just until slightly softened and no longer raw, about 3 minutes. Drain.

Transfer the carrots to a bowl and let cool slightly, then add the chiles and scallion ribbons and toss to mix.

Whisk together the soy sauce, rice vinegar, and sesame oil. Pour over the salad while the carrots are still warm. Stir or toss gently to distribute the dressing, then turn the salad out onto a serving plate or into a wide shallow bowl.

Serve the salad warm or at room temperature. Just before serving, sprinkle on the salt and toss gently, then sprinkle on the coriander and toss again.

Serves 4 as a salad or appetizer

Tibetan family with young child, in western Sichuan.

We met in Lhasa, Naomi and I, in early October 1985. We were both staying in the Snowland Hotel, both in dormitories. At night, a lot of people would meet on the rooftop of the hotel because the nights are beautiful in central Tibet in October, clear and mild, and because the roof was a far better place to sit than the dorm rooms. That’s where we first met, on the roof in the dark.

We started to talk about books, about “Himalayan” literature, and realized that we’d read many of the same books, several of them somewhat obscure (see page 129). And we’d both spent months in Nepal, and Naomi had traveled in Ladakh, the Tibetan region of India. To be traveling in Tibet was a dream for both of us, and for many of the same reasons. So it was easy to talk.

The next day, we went on a bicycle ride together. I was in Lhasa with five friends from my hometown in Wyoming, and we all had bicycles. We were hoping eventually to bicycle across the Himalaya from Lhasa to Kathmandu. A company had given us the bicycles, and another company had given us gear. I’d had the idea for the ride during my Jeep ride to the border six months before (see page 51), but it wasn’t as if we were avid cyclists.

Naomi borrowed a friend’s bike, and we rode outside town, then sat by the river and talked. When we got back to the hotel, we discovered a flat tire on Naomi’s bike. She said she’d help me patch the tire, but I said she should go, I could do it. I didn’t want to tell her, but patching tires wasn’t one of my strong points. I’d gotten myself all the way to Tibet with a bicycle, but knew very little about bicycle repair.

Two days later, we went on a three-day trip in a Jeep, together with two Italian guys Naomi had met earlier in her travels. We were hoping to get to Samye Gompa, the first Buddhist temple built in Tibet (over 1,100 years ago). But as we were walking to the monastery, Naomi and I stopped to talk. And we talked and talked. We never made it to the temple. But by the end of the day, we were talking about having a family together.

My bicycle trip to Kathmandu began ten days later. Six of us rode out of town, imposters all, excited and fearful at the same time. Would we find water on the way? Would we be stopped by the police? Would we be able to cross the passes? When we camped the first night, many of us had flat tires from a nasty kind of thorn that we came to know too well. The following morning, we started the long all-day climb to the top of our first pass, Khamba La, 15,820 feet in elevation (see photo, page 4).

A week later we reached the town of Shigatse in southern Tibet, and there was Naomi! She was traveling by Jeep with a friend named Amy Kratz and two Himalyan anthropologists, Corneille Jest and Gabriel Campbell. That night she and I took our sleeping bags to the roof of the two-story caravanserai-style hotel where we were staying. Across the way was a large monastery, Tashilhunpo, and just outside its gates a crowd of pilgrims, mostly nomads, had set up camp. In the middle of the night, we were awakened by the howling of dogs. When we opened our eyes, we saw that the full moon was going into total eclipse. The dogs went on howling, and the pilgrims began chanting….

Naomi and I will never forget October–November 1985. We rendezvoused again when I got to Kathmandu. We hung out at tea shops and little restaurants, talking and eating apple pie and cinnamon buns. And we planned our next trip back to Tibet. J

Napa and Red Onion Salad

The summers in Inner Mongolia are brief, and during the rest of the year, fresh green vegetables are in short supply. Like people in Tibet and in northern places (the Russians who live just across the border in Siberia, for example, or the Koreans), people in Inner Mongolia have figured out solutions. Cabbages and other vegetables that have been pickled or dried, dried mushrooms, and easily stored root vegetables such as potatoes, carrots, radishes, and turnips, along with cucumbers grown under glass, do stand-in duty for all that is not available.

This crunchy late-autumn salad has beautiful curving shards of red onion tossed with fine shreds of Napa cabbage. One of many salads that we ate in the cold days of late October in Inner Mongolia, it includes elements from both sides of the border: Chinese flavorings are used to dress a Siberian/Russian-style salad, just the thing to add fresh bite to a winter meal. Because it can be made ahead and keeps its flavor and texture, it’s a great dish to take to a potluck dinner.

1 small or ½ medium-large red onion (¼ pound)

2 teaspoons salt, or to taste

2 cups shredded Napa cabbage (see Note)

2 teaspoons roasted sesame oil, or to taste

1 tablespoon minced ginger

1 tablespoon rice vinegar, or to taste

About ½ cup coriander leaves

Slice the onion lengthwise into quarters, then very thinly slice each quarter lengthwise. You should have about 1 cup. Place in a sieve, add 1 teaspoon of the salt, and toss well. Set over a bowl and let stand for 10 minutes to drain.

Meanwhile, place the cabbage in a bowl and pour over boiling water to cover (about 4 cups). Let stand for a minute or two, then drain in a colander. Place back in the bowl and set aside.

Rinse the onion with cold water, then squeeze dry and add to the cabbage. Set aside.

Heat the 2 teaspoons sesame oil in a small wok or small skillet over medium heat. Add the ginger and cook for about 1 minute, stirring frequently to prevent sticking. Add the vinegar, and once it bubbles, pour the mixture over the salad. Toss to blend, then add the remaining 1 teaspoon salt and toss again. The salad can be served immediately or left to stand for up to an hour so flavors can blend.

Just before serving, taste and add a little more sesame oil if you want to bring that flavor forward, as well as more salt if you wish. Add the coriander leaves and toss.

Serves 4 as a salad or appetizer

NOTE ON SHREDDING CABBAGE: To shred the cabbage, slice crosswise into very thin slivers with a cleaver or chef’s knife.

A Mongol woman outside her ger (yurt) in Inner Mongolia.

A young Uighur girl chats with a goat at the busy Sunday bazaar in Kashgar, in western Xinjiang.

In this classic Central Asian salad, onions are salted briefly, then rinsed to wash away their sharpness. It’s like an instant pickling, making them sweeter and more tender. They’re dressed with salt, sugar, and vinegar, then sprinkled with coriander leaves and pomegranate seeds.

Pomegranates come into season around October and are usually available until late January or early February. There are both sweet and tart pomegranates. The sweet ones are much more widely available in North America, and that’s what you want to buy.

2 medium red or white onions (about 1 pound), thinly sliced

1 tablespoon salt, or to taste

3 tablespoons rice vinegar

1 teaspoon crushed rock sugar or regular sugar

½ teaspoon chile pepper flakes (optional)

½ cup chopped coriander

½ cup pomegranate seeds (see Note)

Place the onions in a colander set over a bowl or in the sink, sprinkle on the 1 tablespoon salt, and toss to mix well. Let drain for 15 minutes or so, then rinse well with cold water and gently squeeze out excess liquid. Separate the slices as you place the onions in a shallow bowl.

In a small bowl, mix together the vinegar, sugar, and chile flakes, whisking well to blend them, then pour over the onions. Toss to distribute the dressing. Taste, and add a little salt if needed. Add the coriander and toss, then sprinkle on the pomegranate seeds.

Serves 4 as a salad or side dish

NOTE ON POMEGRANATE TECHNIQUE: To get at the seeds, use the tip of a sharp knife to make a 2-inch square cut in the skin, cutting just through the skin. Lift the cut piece from the rest of the fruit; some seeds will still be attached. Repeat with another section of skin. Now you have easy access to the seeds in the center of the fruit. Separate them from the astringent-tasting pith and heap in a bowl. They’re beautiful, a great garnish for salads and pulaos, and a nice little snack on their own.

Pomegranates, an unexpected reminder of easier milder climates, on sale in the market in Hailar, Inner Mongolia.

When it’s hot and dry, as it is in summertime in the deserts of Xinjiang province, a moist salad is very welcome. The only “dressing” is minced herbs and salt. The salad pairs beautifully with rich pulaos, and with grilled kebabs.

About 1 pound ripe tomatoes

About ½ pound English cucumber

½ pound daikon radish, peeled, or red radishes

2 tablespoons minced scallion greens

¼ cup packed minced herbs: dill, coriander, flat-leaf parsley, or mint, or a mixture

2 teaspoons salt, or to taste

Chop the tomatoes into ½-inch dice or smaller, and place in a bowl. Peel the cucumber, chop into small dice, and add to the tomato. Chop the radish(es) into small dice and add. Add the herbs and salt, and toss to mix well.

Transfer to a wide shallow bowl, and serve immediately.

Serves 6 as a salad or side dish

Uighurs (sometimes written Uygurs) are a Turkic people whose language is related to Uzbek, Kirghiz, and Kazakh. They are the majority non-Han population in Xinjiang. Their current population in China is approximately eight million (smaller groups live in Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkey, and Mongolia). Nearly 85 percent of Xinjiang is desert and/or uncultivatable land, so most Uighurs live in desert oases or in the foothills of the Tian Shan Mountains.

Uighurs have been an important culture in this part of the world since well before the eighth century. (When Genghis Khan took control of a large chunk of Central Asia in the thirteenth century, it was Uighur scribes he relied upon to develop a system for writing and keeping accounts. Although that Uighur script is still the Mongolian alphabet, the Uighur language is now written in a modified Arabic script.) At various times since then, Uighurs have had sovereignty over their homeland or have made alliances with neighboring peoples, enabling them to have local autonomy. For a short period in the 1930s, they formed an independent republic, but it fell back under Chinese rule in 1944.

Prior to the tenth century, Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, Manicheaism, and Animism were all practiced in Xinjiang, but in the tenth to twelfth centuries, Uighurs converted to Islam, and they are now primarily Sunni Muslims. They have a sense of national identity, and there is a vocal Uighur nationalist movement, despite efforts by the government in Beijing to suppress it by imprisoning or sometimes even executing Uighur nationalists.

The Uighurs are primarily farmers and traders. In the desert oases, they farm vegetables, wheat, and fruits (they’re famous for their sweet melons, and for their long sweet grapes and the raisins that are made from them), as well as cotton. The oases are watered by irrigation systems built long ago, which transport water from faraway mountains underground, a system invented by the Persians. Uighurs can also be found in the cities of central China, where they sell street food (kebabs and flatbreads), run Uighur restaurants, and trade traditional Xinjiang products.

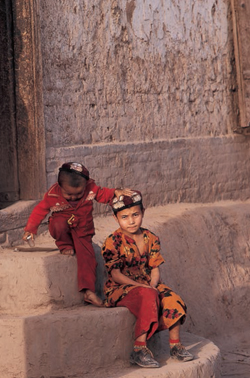

Traditionally, Uighur men wear a small flat embroidered cap. Uighur women cover their heads with colored scarves or brown veils and wear dresses of brightly patterned cotton (see photo, page 209). The fabric is printed with multicolored ikat designs that mimic the ikat-woven silk for which Uighurs have been famous for centuries. (In ikat weaving, the weft threads are dyed before being woven, which results in distinctive soft-edged patterns in the fabric.) Uighurs are also known for their wool-felt rugs.

Everyday foods in the oases are anchored by tea and bread. The breads are leavened flatbreads of various kinds, called nan (see Uighur Nan, page 190) and baked in tandoor ovens. The tea is usually drunk clear, from bowls. The other daily staple is noodles, made of a wheat-flour dough that is stretched and flung in a very distinctive method (see “Uighur Flung Noodles,” page 152). These are usually served in a broth or topped with meat and vegetables (see Laghman Sauce for Noodles, page 135). For feasting and special occasions, the main dish is pulao, rice flavored with meat and vegetables and served on a large platter, family-style (see Chicken Pulao with Pumpkin, page 174).

An older Uighur man stands by a kilometer post in the Altai Mountains, in northern Xinjiang.

Two Uighur children play outside a traditional Central Asian–style house built of sun-dried brick, in Kashgar, western Xinjiang.