Cayenne-style chiles growing by a house in the Miao village of Xijiang, in Guizhou.

Every culture we’ve encountered beyond the Great Wall has salsas or sauces or condiments that are put on the table to heighten flavors and to give guests the chance to vary tastes and add intensity to their food as they eat. We love them for their bright flavors and for their simplicity.

The salsas and chutneys make wonderful accompaniments to grilled meats and deep-fried snacks; we also like to serve them as dips for sticky rice or crackers or bread. We’ve had to restrict ourselves here to just a sampling. There’s a bright red chile paste, made of quickly processed red cayennes (page 18); a tart and enticing grilled vegetable salsa from the Dai of southern Yunnan (page 22); a fresh tomato salsa-like sauce from Guizhou (page 18); a simple green herb sauce from the Mongol repertoire (page 23); and two quick chutneys (page 24) now found in Tibetan communities in central Tibet and in Gansu and Qinghai.

In most areas beyond the Great Wall, and elsewhere in the world where winters are hard, autumn is the time for preserving vegetables and drying meat. In a farmhouse in the far north of Inner Mongolia, with a huge brick-and-tile stove in the kitchen, Naomi saw pails of cabbage in brine slowly turning into pickles, and out in the yard another fermented cabbage pickle, this one turning into something more like Korean kimchi. Pickles and preserves originated as a way of coping with scarcity. Now they’ve become a delicious end in themselves, intense and distinctive ways to bring flavor to a meal.

Many traditional pickled greens, such as pickled mustard greens (see Glossary) and kimchi, are available in Asian grocery stores. We urge you to buy several and sample them. They’re a great addition to the table.

We have included two easy brined recipes, one for a Tibetan white radish pickle (page 25), the other for pickled cayenne chiles, bright red and beautiful (page 34). Both have become pantry staples for us, because they can be served as condiments and are also ingredients in other dishes. Among the other pantry staples in this chapter are hot chile oil (page 29) and Guizhou chile paste (page 35).

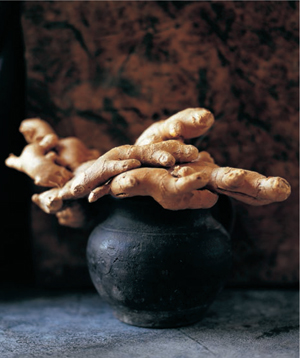

A hand of ginger.

Market Stall Fresh Tomato Salsa and Bright Red Chile Paste.

This couldn’t be simpler. Like all simple dishes, it requires good basic ingredients; make it whenever you have access to ripe local tomatoes. It reminds us of the topping for pa amb tomàquet, the delicious Catalan tomato-smeared bread.

Raw vegetables are a special treat in China, where almost all vegetables are served cooked. I came across fresh tomato salsa in a rural market in Guizhou, in a town called Chong’an. It was one of a number of condiments and toppings at a noodle stand (see Hand-Rolled Rice Noodles, page 142). The fresh flavor of the tomatoes combined with salt and a little sesame oil was like a new discovery.

Serve as a topping for rice noodles or other noodles, as a condiment with any meal, or as a salsa with sticky rice or chips. To use as a topping for noodles, pour over the noodles, either hot or at room temperature, using about 1 cup salsa per serving. To serve as a condiment, put out in a bowl with a spoon.

4 medium-large perfectly ripe thin-skinned tomatoes

1 scallion, minced, or about 1 tablespoon minced chives

½ to 1 teaspoon roasted sesame oil, to taste

1 teaspoon kosher salt or sea salt, or to taste

Working over a bowl to catch the juices, cut the tomatoes into bite-sized pieces and drop them into the bowl. Then squeeze the cut tomatoes a handful at a time to soften them and squeeze out even more juice. Add the minced scallion or chives and sesame oil and stir to mix. Add the salt and stir, then taste and adjust the oil and salt if you wish.

Serves 3 to 4 as a topping for noodles, 6 as a condiment or salsa

We’re accustomed to seeing chile paste, made from dried red chiles and a little oil, set out as a table condiment with noodles and used in kitchens all over China. But we’ve learned that many cooks in Guizhou, Guangxi, and Yunnan also use a fresh sauce, made from red chiles that are very like cayenne chiles. Whenever you come across ripe red cayenne chiles, make up a batch of this paste. The chiles are ground or pounded to a paste with a little salt and a touch of vinegar. The paste is bright red, a beautiful addition to the table.

About ¼ pound (8 to 10) fresh red cayenne chiles

1 teaspoon salt, or to taste

Pinch of sugar (optional)

1 tablespoon rice vinegar

2 tablespoons water, or more to taste

Wash the chiles well, then cut off the stems and coarsely chop the chiles. Place them in a food processor, add the salt, and process to a paste. Add the sugar, if using, and the vinegar and pulse to blend. Turn out into a bowl, using a rubber spatula to scrape the chile paste from the processor bowl, and add water to thin to the texture you desire. With the amount of water suggested above, the paste will be thick and dense with chiles, but it can be made quite thin by adding up to ¼ cup water: it’s up to you. If you make it thinner, you may want to add another pinch of salt.

To serve as a condiment, place in a small shallow bowl and put out a spoon so guests can help themselves to a drizzle of the paste as they eat. To use as a flavoring in stir-fries, add either at the beginning, once the oil in the wok is hot, to give an undernote of warmth (try using 1 teaspoon to start with), or when the dish is almost cooked, to give a fresh dash of heat (use less, perhaps ½ teaspoon).

Stored in a clean glass jar with a tight-fitting lid in the refrigerator, leftover chile paste will keep for a week or so.

Makes a generous ½ cup

Uighur men and boys, full of life and curiosity, at the Sunday bazaar in Kashgar.

It became a cliché in the 1970s, those photographs of Chinese streets crammed with cyclists in somber-colored jackets and pants. Dark blue, dull green, and gray or black were the only colors you’d ever see in the photos, apart from the brilliant red of the Chinese flag. China seemed to be a country in monochrome, a stage set filled with crowds of people all dressed alike, deindividualized and desexualized.

When I went to China for the first time, in the summer of 1980, it looked like those photos, in places. Independent travel was not permitted for casual tourists, so I went with a tour group from the United States. On our one-month trip we traveled by plane, train, and bus to areas beyond the Great Wall (Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia), as well as to various Chinese cities (Beijing, Xi’an, Guangzhou, Taiyuan). We were fed elaborate meals, mostly Chinese regional food prepared by gifted chefs in banquet style, which meant there were many refined dishes and very little rice.

The wide expanses of Tiananmen Square in Beijing were filled with cyclists at rush hour, and the sight of a car was unusual. The cities were quiet, with few horns, just the jingle of bicycle bells and the rumble of wheeled carts. People were nervous about talking with us, but at the same time intensely curious about foreigners. They’d crowd around, but then if they saw an official or a policeman approach they’d melt away, not wanting trouble. It was my first real experience of a totalitarian state.

For more than ten years, during the Cultural Revolution and after (1966–1976), religious and cultural expression was completely suppressed, academics punished or killed, foreign influences rooted out and destroyed. Once Mao died in 1976, there seemed to be a relaxing of the regime. Our guides told us about the fall of the Gang of Four (they had been arrested less than a month after Mao’s death and were blamed for the excesses of the Cultural Revolution) and the Four Modernizations (designed to bring the economy up to speed).

There was talk of greater openness and of greater freedom for private enterprise, religion, and cultural expression. In Xi’an, we visited the main mosque, newly reopened and very beautiful. We learned a little about the Hui (see page 216). In Xinjiang, the Uighur people (see page 90) in Urumqi and Turpan and the Kazakhs in the mountains (see page 157) wore bright colors—the women in skirts and headscarves rather than the drab pants of women in central China, the men still in Mao-style cotton shirts and pants, but with embroidered skullcaps and leather boots that made each person very individual-looking and so unlike the Han.

It was in Xinjiang that we first saw food (mostly stacks of melons, a few vegetables, and flatbreads) for sale in the street. In the cities of Central Asia, the only shopping possibilities were department stores, drab, grim places with not much for sale and very surly government-employed staff with no interest in helping customers. The few well-stocked shelves were those in the foreign-currency section of the stores, where only dollars or other hard currencies were accepted.

I came away from that trip fascinated by my glimpse of the non-Han peoples living in the areas beyond the Great Wall. I wondered how those people felt, dominated by the central government and by the Han majority. I wondered if I would ever be able to travel freely along the Silk Road and in Inner Mongolia, or if I’d ever be able to spend time in Tibet and the tribal areas in the south. It seemed very unlikely at the time…. N

Like their cousins the Lao and the Shan, the Dai people of southern Yunnan are brilliant grillers. They use fire not only to cook but also to impart distinctive flavor to various dishes. We first tasted this olive-green salsa in a Dai household in Menghan, a market town on the Mekong River about a day’s drive from the Lao border.

This salsa is a member of the family of dishes known as jaew in the Tai languages. They’re made of grilled ingredients that are pounded or processed to a sauce, then served as a condiment or as an accompaniment to rice meals. The traditional ingredient here is makawk, a sour fruit known in English as a hog plum (see Glossary for more). A close equivalent in terms of taste and tartness is the North American tomatillo; the recipe gives instructions for both.

The flavors are nicely balanced between the tart-acid of the fruit and the sweetness of the grilled shallots and garlic, and they are anchored by the warm taste of the grill. This is a rare example of a southeast Asian salsa that has no chile heat.

Serve with grilled or roasted meat, such as Dai Grilled Chicken (page 252) or Lisu Spice-Rubbed Roast Pork (page 314), or as a dip for Sticky Rice (see page 162). [PHOTOGRAPH ON PAGE 165]

¾ pound tomatillos (or hog plums, if available; see headnote)

1 cup shallots, preferably Asian shallots (see Glossary), not peeled, halved lengthwise if large

1 medium head garlic cloves, separated but not peeled (about ⅓ cup)

¼ cup water

1 teaspoon salt, or to taste

2 ounces (¼ cup) ground pork

½ cup chopped coriander

If grilling, prepare a medium-hot fire in a charcoal grill or preheat a gas grill. Place the tomatillos (or hog plums), shallots, and garlic cloves on a grill screen or other fine-mesh surface on the grill. Alternatively, place them in two heavy (preferably cast-iron) skillets over medium-high heat. Grill or cook, turning frequently, until well softened and touched with black patches all over, 10 to 15 minutes, depending on your cooking method. Set aside to cool.

Meanwhile, place the water in a small pan and bring to a boil. Add the salt and pork and cook, stirring to break up lumps and to prevent sticking, until all the pork has changed color, about 1 minute. Set aside.

Peel the grilled tomatillos, shallots, and garlic and trim off any very black spots. Place them in a blender or food processor and pulse or process briefly, just until you have a coarse sauce texture. Turn out into a bowl. Add the pork with its cooking liquid, and stir to blend together.

Just before you serve the salsa, stir in the coriander. Taste and adjust the salt if you wish. Serve in a decorative bowl and provide a serving spoon so guests can help themselves.

Leftovers will keep for several days stored in a tightly sealed glass container in the refrigerator.

Makes 2 cups

For three brief months in the summer the grasslands of Inner Mongolia are like a rolling green ocean under a blue, blue sky. A cyclist rides across the grasslands near Ulan Tokay, north of Hohhot.

In Manzhouli, on the border between Inner Mongolia and Siberia, I shared a convivial meal of lamb hot pot at a small lively restaurant with Driver Lin (see page 307) and another friend. Manzhouli is a wild place, as most border towns are, a place where goods and services, both legal and illegal, are bought and sold and lots of money seems to change hands.

The condiments that came with the hot pot were distinctive, as they often are, for every cook adds a twist. The one I particularly liked at this place was a thick green herb salsa spiked with a little vinegar. Here is our take on that bright-tasting sauce.

Serve this to accompany grilled or roast chicken or lamb. We also like it drizzled on pulao or on plain rice.

2 cups packed coriander leaves and stems, or substitute mint leaves

½ cup coarsely chopped scallions (white and tender green parts)

2 tablespoons rice vinegar

¼ teaspoon salt, or to taste

Place the herbs and scallions in a food processor or a mini-chopper and process to a coarse paste. Add the vinegar and salt and pulse to blend. Alternatively, use a mortar and pestle to reduce the greens to a coarse paste, then add the vinegar and salt and mix well. Taste and adjust the seasoning if you wish.

Transfer to a small serving bowl and serve with a small spoon so guests can help themselves.

Makes about ¾ cup

One day a young Tibetan woman named Tsai and I went out for lunch in Labrang, to a small Tibetan café-restaurant up on the second floor, overlooking the main street. Tsai ordered sha-pa-le (see Savory Tibetan Breads, page 214), while I asked for ping sha (see Beef with Mushrooms and Cellophane Noodles, page 280). Her deep-fried breads, small and delicious, came with this mildly spiced tomato chutney. It’s a new thing, the use of a relish or chutney in Tibetan meals; it seems to be connected with the return of Tibetans from India and Nepal.

This is a wonderful accompaniment for Cheese Momos (page 212) or other deep-fried snacks, and it makes a good condiment for grilled or roast lamb and pork.

2 tablespoons peanut oil or vegetable oil

¼ teaspoon cumin seeds or ground cumin

½ cup minced onion

1 dried red chile

½ to 1 teaspoon salt, or to taste

2 medium tomatoes (½ pound total), chopped

½ cup minced coriander or Chinese celery leaves (optional)

Heat the oil in a wok or heavy skillet over medium-high heat. Add the cumin seeds and let them crackle and get aromatic, about 20 seconds (or just 5 seconds for ground cumin), then add the onion and chile. Stir briefly, then add ½ teaspoon salt. Cook, stirring frequently, until the onion is translucent, about 5 minutes.

Add the tomatoes and stir for a minute or so, until they start giving off their liquid.

Bring to a boil, then lower the heat, cover, and simmer until the tomatoes are soft, about 10 minutes. Remove the cover, lower the heat, and simmer a little longer, to reduce the liquid slightly.

Taste for salt and adjust if you wish. (We like this slightly salty, especially if we’re serving it with grilled or roast meat, so we usually add at least another ½ teaspoon.) Just before serving, stir in the herbs, if using.

Makes a generous 1 cup

TIBETAN GINGER-TOMATO CHUTNEY: I encountered another version of this salsa-like condiment in Lhasa. There the touch of heat came from ginger rather than from dried red chile. Substitute 1 tablespoon minced ginger for the dried chile. This chutney pairs especially well with beef dishes. [PHOTOGRAPH ON PAGE 153]

We’ve been struck by how often there’s a little radish included in Tibetan dishes (see Tsampa Soup, page 47, for example). The radishes in Tibet are large and mostly white, like high-altitude cousins of the daikon radish (known also as icicle radish, or by its Hindi name, mooli). Some have a blush of pink on them, and they are sometimes rounded rather than long and straight. In this book we’ve called for daikon whenever Tibetan radish is traditionally used.

In Tibet, radishes also come to the table as a condiment, like a concentrated little salad. The radish is grated, then stored with flavorings in a vinegar brine and allowed to stand; in a few days, it’s ready to be eaten. Like any household standby, radish pickle can vary a lot, depending on the cook’s tastes or family traditions.

We learned our version from our friend Tenzin, in Lhasa. We have known him since the first time we were in Tibet, in 1985, when he ran the travelers’ hostel we stayed at near the Jokhang Temple. Each time we planned to stay in Lhasa, we’d write ahead to Tenzin to try to book our favorite room. We’d give him English lessons, sitting out on the roof, looking over the old section of Lhasa, with its flat rooftops, to the golden ornaments on the Jokhang Temple and the hills beyond.

When I returned to Lhasa after a gap of nineteen years, I found Tenzin married and with a good job. It was wonderful to see him so settled and content. I had a lot of food questions for him, and we spent time in his kitchen talking about basics, including this pickle. Tenzin told me that some people also put in garlic or MSG. We prefer to flavor ours with only ginger, Sichuan pepper, scallion, and a little onion.

This pickle is very tart and vinegary (though it mellows over time), and is meant to be eaten as a condiment, an accompaniment to meat and rice, not on its own. (But I also love to eat it a nontraditional way: I start with good bread, perhaps lightly toasted, spread on unsalted butter, then top it with generous clumps of pickled radish.)

The radish is cut into long, thin shreds, which we do using a coarse grater; you could also slice it into julienne using a Benriner or other vegetable slicer. The shreds are placed in a jar with the flavorings, the salt and vinegar are added, and the jar is sealed and shaken to mix all the flavors. Then it’s set in the sun to ferment for a couple of days. In warm weather, the pickle is ready in 2 days; in colder weather, or with cloudy days, allow 4 days.

Because daikon radish is available all year round, this quick pickle can be made at any time of year and stored in the refrigerator for weeks. When the jar starts to run low, it’s time to make another batch.

1 pound daikon radish, peeled and coarsely grated or thinly sliced (see headnote)

2 medium scallions, minced

½ small onion, cut into thin slices

About 2 tablespoons minced ginger

2 tablespoons kosher salt

1 to 2 tablespoons minced garlic (optional)

1 teaspoon dry-roasted Sichuan peppercorns, ground (optional)

About 3 cups rice vinegar

Place the radish, scallions, onion, and ginger in a large bowl and toss to mix them well. Stuff half the mixture into a sterilized 4-quart jar and add 1 tablespoon of the salt and the garlic and/or Sichuan pepper if you wish. Add the remaining radish mixture and the second tablespoon of salt, and pour on the vinegar, which should cover the mixture completely. Seal and shake the jar to distribute the vinegar well.

Place in a sunny spot by a window for 2 to 4 days (see headnote), giving the jar a shake occasionally to help blend the flavors. It is now ready to use. The pickle will keep indefinitely if well sealed and refrigerated.

To serve, use a clean spoon or fork or chopsticks to lift out a clump of radish strands and place them in a condiment bowl.

Makes 4 cups

An older monk, a man who lived through the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, sits outside the temple in Gyantse, in central Tibet, reading prayers from the book in his lap.

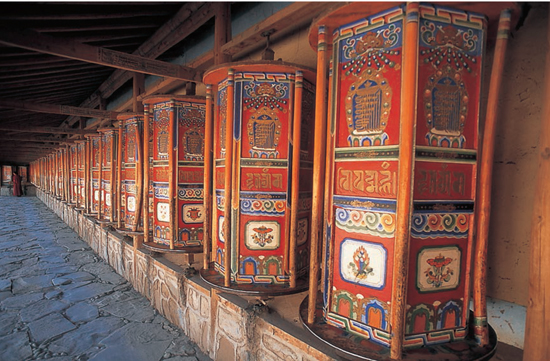

At the huge Tibetan Buddhist monastery of Labrang, in the province of Gansu, the walls around the complex are lined with tall prayer wheels. The devout give each prayer wheel a vigorous turn as they walk past, always circumambulating the temples in a clockwise direction.

This condiment for rice from the Hani people of the hills of southern Yunnan (see page 316) uses garlic and shallots that are quickly grilled, then pounded to a paste with chiles and salt. The sauce is thick and spicy hot, a great condiment for grilled meats of all kinds.

1 medium head garlic, cloves separated but not peeled

2 shallots, not peeled

¼ teaspoon salt, or to taste

3 fresh bird chiles or serrano chiles

Place the unpeeled garlic and shallots in the coals of a fire or in a gas flame (on a stovetop or grill) and cook, turning occasionally, until well blackened; alternatively, place on a lightly oiled baking sheet and roast in a 400°F oven until softened, 15 to 20 minutes. Remove and let cool.

Peel off the blackened outer layers, then coarsely chop the garlic and shallots. Place in a mortar or food processor with the salt. Slice off and discard the stems of the chiles, then coarsely chop the chiles and add to the other ingredients. Pound or process to a coarse paste.

Transfer to a small dish and serve with a small spoon.

Makes a scant ¼ cup

MONGOLIAN ROASTED GARLIC PASTE: In northeastern Inner Mongolia, I came across another version of garlic paste, served as a condiment with Beef Hot Pot (page 282). It complements Mongolian Barbecue (page 263) and all kinds of grilled meat very well. Use 1 cup unpeeled garlic cloves (about 2 large heads), ¼ to ½ teaspoon cayenne, ½ teaspoon salt, and ¼ teaspoon roasted sesame oil. Cook the garlic as above. Then cut off the end of each clove, squeeze the flesh from the skin, and mash it in a small bowl or a mortar. Stir in the cayenne, salt, and sesame oil and serve warm or at room temperature.

Makes about ¼ cup

Lhasa Yellow Achar

The term achar is used in Nepal (and, farther afield, in Malaysia) for any side relish or chutney. It’s a word to set your mouth tingling and watering with anticipation. And it’s a word that is now quite common in Lhasa, as a number of Tibetans who were once in exile have come back and opened small restaurants, often staffed by cooks from Nepal.

This little side dish is tart from its basic ingredient, Tenzin’s Quick-Pickled Radish Threads, and pale yellow from turmeric. It is a wonderful foil for the lushness of deep-fried snacks such as Cheese Momos (page 212) and for meat dishes such as Lisu Spice-Rubbed Roast Pork (page 314), Classic Lhasa Beef and Potato Stew (page 283), or Keshmah Kebabs (page 262).

1 to 2 tablespoons peanut, canola, or vegetable oil

1 tablespoon minced ginger

¼ cup minced onion or shallots

1 teaspoon ground cumin

½ teaspoon ground coriander

1 teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon Chile Oil (page 29), Guizhou Chile Paste (page 35), or store-bought chile paste, or substitute ¼ teaspoon cayenne, or to taste

1 cup Tenzin’s Quick-Pickled Radish Threads (page 25)

1 teaspoon turmeric

½ cup coarsely chopped coriander

Place a wok or heavy skillet over medium-high heat. Add the oil, then add the ginger and onion or shallots and stir-fry briefly. Toss in the cumin, coriander, salt, and chile oil or paste or cayenne. Stir-fry until the onion or shallots are tender, about 2 minutes. Add the radish pickle and turmeric and cook, stirring frequently to prevent sticking, until the flavors have blended, 2 to 3 minutes. Turn out into a bowl.

Just before serving, stir in the chopped coriander. Store leftovers in a nonreactive container in the refrigerator for no more than 2 days.

Makes 1 cup

Chile oil is one of those simple additions to the pantry that you are likely to find yourself using in all sorts of ways. Although you can buy it in Chinese and Southeast Asian grocery stores, the commercial version is usually made with cottonseed oil, which has an unpleasant aftertaste. Better to quickly make up a batch yourself. It keeps well in the refrigerator. Add a dash of it to spike a salad dressing or a stir-fry, or include it in a dipping sauce.

1 cup peanut oil or vegetable oil

5 to 6 tablespoons chile pepper flakes or crushed dried red chiles

Heat the oil in a wok or skillet until just starting to smoke. Remove from the heat and toss in the dried chile flakes or pieces. Let stand until cooled to room temperature.

Transfer to a clean, dry glass jar and store, well-sealed, in the refrigerator. The chiles will continue infusing the oil.

To use, scoop out the oil, or a mixture of oil and chile flakes, with a clean, dry spoon. You can also, after a week or so, strain the chile out, leaving you with a beautiful clear reddish orange oil.

Makes about 1 cup

We’ve eaten this ginger paste at market stalls in Yunnan, served as a spicy topping for rice-noodle soups or for fermented rice curd. Ginger is pounded to a paste in a mortar with some salt, then blended with a little water to extend it. Dollop it on hot chicken noodle or rice soups to give them an extra spike of flavor, especially in the winter, when warming tastes are most welcome. Put a tablespoon or so of ginger paste on top of your bowl of hot soup, then stir in as you eat. You can also use it as a topping for cubes of fresh tofu.

½ cup chopped ginger

Pinch of salt

Water as needed

Place the ginger and salt in a large mortar or in a food processor and pound or process to a paste. Transfer to a bowl, and stir in a little water to make a smooth paste.

Makes about ⅓ cup

At a market near Dali, Yunnan, in the drizzle of late monsoon rains, a woman eats a bowl of rice noodles topped with various condiments.

Naomi traveled to China for the first time in 1980 (see “Summer 1980,” page 21) but we didn’t know each other then, and my first trip was later. In 1982, I was living in Taipei, Taiwan, working as an English teacher, studying some Mandarin, and taking cooking classes. Every once in a while I’d hear a story about someone visiting “the Mainland,” traveling independently, but it seemed very hard to believe. The rumor was that a visa could be arranged in Hong Kong from a travel agent in Chungking Mansions, a low-life building full of bottom-end hostels, Indian restaurants, and drug deals. It all seemed a bit unlikely—it was “Communist China,” after all.

But the rumor persisted, and before long I met people who’d made the trip. At first, only seven cities in China were open to independent travelers. After that it became thirteen, then twenty-one. If you were traveling on a train or a bus and it stopped in a “closed” town or city, you weren’t allowed to get off. No one seemed to know exactly why some cities were closed and others open. One obvious reason was that China had very little infrastructure for foreigners, very few hotels, very few restaurants. But China was also highly xenophobic. The biggest question was really why the Chinese government was allowing independent travel at all.

My first trip came in March 1984. I got my visa in Hong Kong and caught a boat to Guangzhou, another boat overnight up the Pearl River, then a local bus to a town called Yangshuo, in Guangxi, a place other travelers had told me to go. In Yangshuo, I stayed in People’s Hotel Number One (not that there was a Number Two). On my second night, there was torrential rain and the whole ground floor flooded with several feet of water, so I was moved to the second floor.

Every day was interesting. I watched fishermen fishing with cormorants on the river, and in the countryside outside town, I walked through intensely gardened fields. Eating was a big puzzle. There was only one restaurant in Yangshuo, the People’s Restaurant, and it had very strict hours that weren’t immediately obvious to me. Breakfast began at something like six A.M. and finished exactly ninety minutes later. If you missed it by one minute, you wouldn’t be served. And the same for lunch and dinner. It was like eating in a school cafeteria, only far more militaristic and several degrees gloomier.

Upon entering the restaurant, I first had to purchase little coupons from a sullen clerk who sat behind a tiny barred window, then take the coupons to another place, where I’d be served. My problem was I had no idea what was available, or what the price was. And, unlike almost anywhere else in the world, the people working there were almost unanimously not interested in helping or in being nice. It was institutional China, something I would learn a lot about in the years to come.

The food itself was great, simple but great. In the morning, I’d have hot soybean milk and flatbreads filled with buckwheat honey. For lunch and dinner, I’d eat a big bowl of rice served with a plate of stir-fried local greens, and another of spicy stir-fried tofu. Beer was available, though it required a separate coupon from a different clerk. It came served in a large soup bowl and cost ten fen, which was about two and a half cents.

From Yangshuo I traveled by train to Kunming, and then by bus to the small walled town of Dali, another place I’d been told to visit. Dali was a Bai town, not a Han town, and the feel was different, more relaxed, and more friendly. J

A Bai woman tries on a bracelet at the market in Xiapin, near Dali. She’s wearing traditional clothing, and her basket is supported by a tump line so that her head takes the weight, a method used by many cultures in Yunnan and Southeast Asia.

A child explores a huge mortar and its contents of pounded dried red chiles, at the market in the Dai town of Menghan in southern Yunnan.

Chiles for sale in the mist and fog of Yuanyang, in the hills of southeastern Yunnan.

Pickled Red Chiles

Pickling is an age-old way of storing seasonally available ingredients; it’s also a way of lengthening the time you can keep any fresh ingredient successfully. Pickled chiles are a staple in many places beyond the Great Wall, as well as in parts of central China. They are, we’ve discovered, very handy and easy to have on hand. Over time, the heat of the chiles becomes a little muted, and the balance of flavors shifts toward slightly sweet, but the chiles keep their bright color and some texture too. We now rely on them as a staple. You can use them in place of fresh chiles when stir-frying (for example, in Pork with Napa Cabbage and Chiles, page 298) or put them out as a table condiment (especially when serving Hui-style lamb dishes, or any grilled meat).

You can buy jars of bright red “made-in-Thailand” pickled chiles in many Asian groceries, but they are sweeter and hotter than the pickled chiles we’ve come across in the outlying mountain and desert areas of China, from Yunnan and Guizhou to Qinghai and Xinjiang. And it’s very easy to make your own. These Yunnanese-style pickled chiles are less hot than the Thai version and have no added sweetness. They’re spiked with a little Sichuan pepper. Make up a batch when you come across very red ripe cayenne chiles. You can increase the yield by scaling the recipe up in proportion.

About ¼ pound red cayenne chiles (about eight 6-inch-long chiles) (see Note on Chile Alternatives)

1 cup rice vinegar

1 tablespoon kosher salt

¼ teaspoon Sichuan peppercorns

1 star anise, whole or in pieces (optional)

Wash the chiles, and cut off the stems. Cut into approximately ½-inch slices. Measure out 1 cup and set aside.

Heat the vinegar in a nonreactive pan. Add the salt and stir until it dissolves. Add the peppercorns and star anise, if using. Bring to a boil, then lower the heat and simmer for 30 seconds or so. Remove from the heat and let cool to lukewarm.

Meanwhile, sterilize a 1-cup canning jar, lid, and ring.

Stuff the sliced chiles into the jar, pressing down to compact them a little. Transfer the vinegar and spices to a cup with a spout and then slowly pour the liquid and spices into the jar, filling it right to the top. (You may have several tablespoons of vinegar left.) Put on the lid and then screw the ring on tightly.

Set the jar in a sunny spot for 2 days, then refrigerate. The pickles will be ready in 2 weeks and will keep well for 3 months.

Makes 1 cup

NOTE ON CHILE ALTERNATIVES: If you can’t find cayennes, you can use serranos, which are smaller than cayennes and have more chile heat. To balance that, we suggest that you strip out their seeds before slicing them: cut off the stem ends, then cut a slit lengthwise in each chile, strip out the seeds, and discard.

NOTE ON PICKLING METHOD: The method here and for Tenzin’s Quick-Pickled Radish Threads (page 25) calls for the vinegared and brined raw ingredients to be set out in the sun. It’s a traditional method we have seen in Tibet, Guizhou, and Yunnan. Perhaps the warmth or the sunlight encourages fermentation, but we don’t know the why, only that it’s the usual way. The pickled chiles need more time to soak and soften than the radish threads, and we call for refrigeration for that process, though they could also be stored in a cool cupboard.

QUICK PICKLED CHILES: To make up a last-minute version, say for use in a recipe, or to put out as an improvised condiment, start with fresh red cayennes. Strip out the seeds, then slice as above and place in a bowl. Bring the hot vinegar, salt, and spice mixture to a boil, then pour over the sliced chiles. Put a small plate or lid on top to weight the chiles down so they stay immersed. Let stand for half an hour or more before draining and serving.

We love chile pastes and condiments of all kinds. They highlight the tastes of the foods they accompany and complement them, and they give each person a chance to custom-flavor every mouthful. Once you’ve made chile paste, it sits handily in the refrigerator, ready to add heat and dimension to any meal.

We’ve encountered all kinds of chile pastes in our wanderings beyond the Great Wall. As with chile pastes from other parts of the world (such as North African harissa and Lao jaew), the basic ingredient is dried red chiles. After that, the options are many. In Guizhou, a hilly province in southern China bordered by four other provinces—Sichuan, Yunnan, Hunan, and Guangxi—Sichuan pepper is used a great deal (though not in the overwhelming way it often is in Sichuan). So the chile pastes we’ve encountered there usually have a hint or more of Sichuan pepper, as this recipe does, and no sweetness at all.

1 cup dried red chiles, stemmed

1 cup boiling water

1 teaspoon salt

2 tablespoons peanut oil or vegetable oil

2 tablespoons minced shallots

1 teaspoon Sichuan peppercorns, ground (see Note)

1 tablespoon rice vinegar

Place the chiles in a bowl and pour the boiling water over. Weight the chiles down with a small lid or plate to keep them immersed in the water. Let soak for an hour, or until softened.

Transfer the chiles and soaking water to a food processor. Add the salt and process to a puree. Return the puree to the bowl.

Heat a wok over high heat. Add the oil and lower the heat to medium, then toss in the shallots and Sichuan pepper and stir-fry until the shallots are translucent, 2 to 3 minutes. Add the chile puree (watch out for spattering) and bring to a boil, then reduce the heat and simmer, stirring frequently, for about 5 minutes, until the liquid is reduced by half or so.

Transfer to a bowl and stir in the vinegar. Let cool before transferring to a clean, dry glass jar, and tightly seal with a clean lid. Store in the refrigerator.

Makes a generous ½ cup

NOTE ON SICHUAN PEPPER: Sichuan pepper has a distinctive taste and effect on the mouth. If you love it, then do feel free to increase the quantity here to 1½ or 2 teaspoons. The chile paste will then have, besides chile heat, some of the tongue-numbing powers of Sichuan pepper, as well as a stronger hit of flavor.

ALL-PURPOSE GUIZHOU BASTING SAUCE FOR THE GRILL: If you are grilling meat, fish, or vegetables, Guizhou Chile Paste diluted with oil makes a dynamite basting sauce. Use 1 teaspoon chile paste for every 2 tablespoons peanut oil or vegetable oil. Whisk well to blend them together, then brush lightly onto your meat or fish or vegetables before you grill. Brush again with the flavored oil (whisk just before you do) shortly before you remove the food from the heat.

Outside the Dong village of Zhaoxing, in Guizhou, on a path leading up a hillside past rice terraces and small streams, we came upon a shrine presided over by these totemic figures. Offerings of flowers and of rice and water were in front of them. The Dong are animists, with different villages and areas worshipping slightly different beings, so we don’t know exactly who these figures represent.

People who grill meat know that a simple spice rub can transform flavors, and textures too. Beyond the Great Wall, a simple pepper-salt (a roughly 3 to 1 blend of salt and ground toasted Sichuan pepper) is often used as a seasoning and spice rub. But a number of the peoples who live in the hills and valleys of southern Yunnan and of Guizhou provinces have a more chile-hot take on the classic.

We learned this version of pepper-salt when eating in a Dai household (see page 237) in southern Yunnan. Later we met it again in the food of the Miao (page 183) and the Dong (page 120) in Guizhou, as well as among the Yi (page 316) near the Vietnamese border in Yunnan. Use it as a dry rub on meat before roasting or grilling; put it out on the table as a condiment; add it to oil (see Pepper-Salt Basting Oil, below); or use in other recipes as suggested.

Consider the recipe proportions here as a guide. You may choose to alter them once you’ve tried the pepper-salt. Another option is to substitute black peppercorns for the dried red chiles.

3 dried red chiles or 2 teaspoons black peppercorns

2 tablespoons kosher salt

1 teaspoon Sichuan peppercorns

If using dried chiles, dry-roast them in a small heavy skillet over medium-high heat until they soften, about 1 minute. Turn out and coarsely chop; discard any tough stems. Transfer to a spice grinder or clean coffee grinder, or to a mortar, add 1 tablespoon of the salt, and grind or pound to a powder. Turn out into a bowl and set aside.

Place the Sichuan peppercorns, and the black peppercorns, if using, in the skillet and dry-roast until just aromatic, 1 to 2 minutes. Transfer to the spice or coffee grinder or mortar, add the remaining 1 tablespoon salt (or the 2 tablespoons if you aren’t using dried chiles) and grind or pound to a powder. Add the powder to the ground chile-salt. Let cool completely before storing in a clean glass jar.

Makes about 3 tablespoons

PEPPER-SALT BASTING OIL: Use the pepper-salt to flavor oil, for basting when you are grilling food. Stir about 1 tablespoon powder into ¼ cup oil (we like it in olive oil, as well as in more traditional peanut oil or lard). Brush onto vegetables or meat just before you grill and/or as they are grilling.

Two kinds of heat: on the left are Sichuan peppercorns and on the right, flakes of dried red chile.

If you look for Tibet on a current map of China, what you will find is an area labeled Tibet Autonomous Region. The TAR, as it is often referred to, is a province of the People’s Republic of China. Following the Revolution in China, in 1949, the Beijing government took military control of Tibet’s eastern areas in 1950, and then of central and western Tibet in 1959, when the Dalai Lama fled to India along with many monks and other Tibetans. The borders of Tibet were redrawn so that most of its eastern region (Kham) and northeastern region (Amdo) became part of the neighboring provinces.

Ethnographic (or cultural) Tibet is much larger than the TAR. More than half the Tibetans in China live outside the TAR, primarily in neighboring areas in the provinces of Qinghai, Sichuan, and Yunnan. (It is difficult to find accurate population figures for all Tibetans living in China; published estimates vary from four to six million.)

It is in the majority Tibetan areas adjacent to the TAR, as well as in far western Tibet, that we’ve encountered Tibetans living most traditionally. Lhasa and nearby areas of central Tibet are the focus of a huge amount of Chinese military control. The Tibetan population there has been swamped by masses of Han (Chinese) and Hui (Chinese Muslim) migration for two generations, and Tibetan life there has been closely monitored and restricted by the authorities since 1959. There are still Tibetan political prisoners in China.

Because Tibetan-inhabited areas range over a vast and diverse region, Tibetan food varies widely. In the fertile valleys of central and eastern Tibet, many kinds of vegetables and several grains (wheat and barley) are grown, as well as rapeseed (canola), raised for its oil.

Houses are usually built of stone, beautiful and solid, with small multipaned windows. In some forested parts of the Kham region (in the Tibetan areas of Sichuan and Yunnan provinces), houses are traditionally built of wood. The livestock (yaks; yak-cow crossbreeds called dzomo, used for milk; and goats and sheep) occupy the ground level, while the living quarters are upstairs, where it is warmer and sunnier. The flat rooftops are used for drying vegetables, meat, chiles, and firewood, possible because most of Tibet is high desert with relatively little snow or rain.

In the high-altitude regions of western Tibet and Qinghai, Tibetan nomads move with their herds from grazing ground to grazing ground. The nomads are known as Drogpa, or Golok, and live in wool-felt tents (canvas in the summer) that can be packed up onto the yaks when it’s time to move camp. The nomads live from their herds, selling the wool from the sheep and goats to traders and using the money to buy tea as well as barley. Some gather salt from the saline lakes of the high plateau, which they sell to traders; others gather medicinal plants to sell.

The government restricts the areas in which the nomads graze their herds, especially in the eastern and northeastern regions, arguing that the nomads will have better access to education and health care if they settle into fixed communities, and that there will be less overgrazing. But this idea is highly controversial, because it involves changing a lifestyle that has been in place for generations, and one that is uniquely adapted to the environment. No matter which side one agrees with, it is deeply disturbing to see lines of wire fencing running across what for centuries was wide-open grassland.

Tibetan families sit watching a school event in Litang. In this town in western Sichuan, as in most majority-Tibetan areas outside the Tibetan Autonomous Region, Tibetan culture feels relatively strong and vibrant. The woman on the right is spinning a prayer wheel as she talks to the baby. Inside the wheel are printed prayers.

An older woman in Lhasa smiles at us as she makes her way around the Barkhor, the circular route around the Jokhang temple, a place of pilgrimage and prayer in the center of Lhasa. She holds her string of prayer beads in her left hand.