A street in the predominantly Bai town of Dali, by Lake Er Hai in Yunnan. A man walks by a house where cabbage greens (a winter vegetable) are strung on a line under the eaves to dry in the cool winter sun. The next step will be to pickle them.

In the Southern Provinces of Yunnan and Guizhou, with their milder climates and abundant rainfall, cooks have a wide array of vegetables to choose from year-round, but in Inner Mongolia and Tibet, and in Gansu, Qinghai, and Xinjiang, during the long, cold winter, the word “vegetable” comes to mean potatoes, carrots, radishes, and other hardy root crops, as it did until recently in northern Europe. And, as in European tradition, in these colder areas beyond the Great Wall, a little meat or meat broth is often part of the recipe, giving it depth and succulence. Sometimes, especially in dishes from the mountain tradition, we have the impression that the vegetables are just there as a way of extending the flavor of the meat (see Kazakh Cabbage Stir-Fry with Lamb, page 100). In Yunnan and Guizhou provinces, as in much of central China, the vegetable dishes are often flavored with a little pork (see Ginger and Carrot Stir-Fry, page 96, for example). Alternatively, tofu sticks or other forms of tofu are added to vegetable stir-fries and simmered dishes, to give more substance (see Jicama–Tofu Sheet Stir-Fry, page 105).

With the recent influx of Han and Hui people from central China into Tibet, there is a much greater variety of vegetables in the markets there, especially in the larger towns. There are also more vegetables available now in Qinghai and Gansu provinces (see Hui Vegetable Hot Pot, page 117). Some are being shipped in, but many are grown locally in greenhouses in the valleys near the towns.

You’ll find vegetable dishes in the Salads chapter too, of course, and also in Condiments and Seasonings, in the form of fresh sauces and chutneys, as well as pickles.

Napa cabbage, also known as Chinese cabbage or Chinese lettuce.

Ginger and Carrot Stir-fry

I first tasted this root vegetable stir-fry at a little eatery in Xijiang, a large Miao village (see page 183) in Guizhou. It’s an ideal fall and winter dish, and a great way to prepare carrots. They are cut into strips, then stir-fried with lots of ginger cut the same way.

The chopping takes a little attention. Start with two “fingers” of firm, nonfibrous ginger. Peel them and cut lengthwise in half before cutting them into narrower lengthwise sticks. Do the same with the carrots.

There’s great depth of flavor from the small amount of pork that flavors the cooking oil, and plenty of sauce to spoon onto your rice. Ever since the first time we tried to reproduce the dish in our kitchen, it’s been a big weeknight supper favorite.

2 tablespoons peanut oil or lard

1 tablespoon minced garlic

⅓ pound boneless pork butt, shoulder, or loin, thinly sliced and cut into ½-by-1½-inch strips

2 whole green cayenne chiles or 3 dried red chiles

About ⅔ pound carrots, peeled and cut into matchsticks (1⅓ cups)

About ⅓ pound ginger, peeled and cut into matchsticks (1 cup)

½ teaspoon salt

1 cup water

10 to 12 Sichuan peppercorns, lightly crushed or coarsely ground

2 tablespoons soy sauce, or to taste

Heat a wok or wide heavy skillet over high heat. Add the oil or lard and swirl to coat the bottom of the pan. Toss in the garlic and stir-fry for 10 seconds or so, then toss in the pork and chiles. Stir-fry, separating the pieces of meat so all get exposed to the hot pan, until they have started to change color all over, less than 2 minutes.

Toss in the carrots and ginger and stir-fry for about a minute. Add the salt and stir-fry for another minute. Add the water, cover, and boil vigorously for about 3 minutes, then remove the lid and let the liquid boil down for a minute or two. Add the Sichuan peppercorns and soy sauce. Stir-fry for another minute, or until the carrots and ginger are tender but still firm.

Turn the stir-fry out onto a shallow bowl and serve hot or warm.

Serves 4 as a side dish or as part of a rice meal

A pile of yellow carrots at the market in the Turpan oasis in Xinjiang; we’ve also seen dark purple and burgundy-colored carrots in markets beyond the Great Wall.

Before traveling in Tibet, we’d thought of ourselves as pretty good with campfires. We’d both grown up in places where campfires were a treasured part of summer and fall, Naomi in Ontario, and I in Wyoming. We both knew how to build a fire, how to get a fire going in the rain, all the normal sort of stuff. And we’d also been around hearths and fires in many places around the world, watching people cook. But Tibet was a different experience altogether.

In April 1986, we hired a driver and a bare-bones Toyota Land Cruiser to make a trip from Lhasa, in central Tibet, to Mount Kailas, in far western Tibet. The first few nights along the way, we stopped in towns where there were hotels with little “restaurants” attached, really sort of truck-stop versions of Lhasa hotel eateries, where cooks prepared food in large woks set over massive wood fires. By the third and fourth nights, we were in sparsely populated areas, and the “truck stops” became small, single-floor concrete-block buildings with dorm beds, thermoses of boiled water, and piles of dried yak dung for making a fire.

We hadn’t had much experience building fires with dung, but we’d watched a lot of people cooking over dung fires, so we were ready to have a try. It was relatively easy, especially if we had a little paper to get the fire going. What we could cook was limited by the altitude (water boils at a lower temperature at high altitudes, so white rice was edible after an hour; potatoes took longer). In any case it was pleasant, as it always is, to have a fire going. Nights are cold in April in Tibet.

A few days later, we were in the Changtang area of western Tibet, a high desert plateau dotted with small lakes, most of them salt lakes. The only people around were nomads or the very occasional Chinese truck driver or Tibetan trader, and the “road” was more like traces in the dirt (something like following the Oregon Trail one hundred years too late). We traveled fifteen to twenty miles per hour, always holding on to something in the car to brace against the constant bumps. At the end of a long day, we welcomed the sight of a truck stop. But we were now at fifteen thousand feet. And for some reason, there was no more yak dung. Instead, there were enormous piles of dried goat dung.

Still, we were feeling confident by this time. We built a little tower with paper and dung, and then lit a match. The paper burned, but not the dung. We just couldn’t get it to catch fire. Finally we went to ask a truck driver, a guy standing around outside. He looked at us with a mix of pity and disgust, then walked over to his truck, took off a large gas can (in the Changtang, everyone has to travel carrying extra gas), and brought it into the room. He poured some gas onto our pile of goat dung and lit a match. Whoosh! Suddenly we had a fire. The best thing about goat dung, we learned, is that there’s usually plenty of it.

A few days later, we came across a man out in the middle of nowhere whose truck had gotten stuck in the sand of a dry riverbed. We stopped, and everyone worked, pushing and digging. Once the truck was freed, it was time for lunch. As we started eating our dried yak jerky and our 761 bars, the truck driver dug around in his cab and then appeared with a couple of cans of preserved meat (they were somewhat ubiquitous at that time in China). He put the cans on the ground in front of his truck, went around back, and reappeared with a blowtorch. He took aim, then lit up the scene with a flash of flame, sizzling the cans for about ten seconds. A minute later, when they’d cooled a little, he cut them open and offered us some meat. Cooking with fire, high-altitude-trucker-style.

A Tibetan woman pilgrim in the Mount Kailas region of western Tibet places a stone on a cairn topped with prayer flags and other offerings.

The day after Serik and I had our fall on the motorbike (see page 300), we drove back along the same mountain road and stopped in at the house of the people who had been so nice to us the day before. The small log house sat all by itself just off the road, miles from the nearest settlement. A big dog barked as we arrived, and soon the couple (and their daughter) came out to see who’d driven up. They smiled to see us, then they looked closely at Serik’s wounds and made sure that he was okay. They asked us to come in.

Near the door there was a cast-iron wood-burning stove, fully stoked, so the house was warm and cozy. Cigarettes, which are still a big thing all across China, were passed around, and then cups of hot salted tea. The husband, a tall, friendly Chinese man, put Uighur music on a small stereo, and his wife, a Kazakh, set about chopping onions and slicing cabbage. They showed me photographs of their house in winter (a long, hard winter, just a stone’s throw from Siberia in Russia), and I showed them photographs from Canada. We talked about horses (they have twelve), and about Uighur music, and Kazakh music.

Then lunch was ready. We ate this simple, delicious stir-fry, Kazakh bread (see page 195), several different jams, and yogurt, and drank bowls of salty butter tea.

Since we first worked on this recipe at home, we’ve gotten into the habit of buying just a little bit of lamb, several small chops, for example. We cut the meat off the bone, then mince it with a cleaver. Its delectable flavor goes a long way, not just in this dish, but in other stir-fries too.

1 tablespoon peanut oil, vegetable oil, or rendered lamb fat (see Glossary)

A scant ¼ pound boneless lamb, finely chopped or ground

½ red onion, thinly sliced

1 red cayenne chile, seeds and membranes removed and thinly sliced

1 green cayenne chile, seeds and membranes removed and thinly sliced

1 pound Napa cabbage, thinly sliced crosswise (about 5 cups)

½ teaspoon salt, or to taste

Place a wok over high heat, and once it is hot, add the oil and swirl a little. Toss in the lamb and red onion and stir-fry for 1 minute. Add the chiles and stir-fry for 15 seconds, then add the cabbage. Stir-fry briefly, then add the salt and continue to stir-fry for 3 to 4 minutes, or until the cabbage is wilted and tender. Taste and adjust the salt if you wish.

Turn out onto a plate and serve.

Serves 3 to 4 as one of several dishes

On a recent trip to Lhasa, I had several versions of this simmered tomato-eggplant stir-fry in small Tibetan-run restaurants and in one private home. The dish was new to me, a sign perhaps of the greater availability of vegetables in Lhasa and a greater preparedness among younger Tibetans, at least those in the larger towns, to eat more vegetables. Make it in mid- to late summer when vegetables are at their peak; or substitute canned tomatoes in other seasons. Serve with plenty of rice to absorb the full-flavored ginger-garlic broth. There’s no chile or chile paste in the dish, but there is a small taste of China: a touch of Sichuan pepper and a hit of soy sauce.

2 long or 4 short Asian eggplants (about 1 pound total)

2 to 3 medium tomatoes (¾ to 1 pound), or substitute 2 cups canned tomatoes

2 scallions

2 tablespoons peanut oil or vegetable oil

1 tablespoon minced garlic

1 tablespoon minced ginger

2 teaspoons salt, or to taste (less if your broth is salty)

¼ teaspoon ground Sichuan pepper, or to taste

½ to ¾ cup Tibetan Bone Broth (page 45) or mild vegetable, chicken, or meat broth

1 tablespoon soy sauce, or to taste

Trim the stems off the eggplants. Cut lengthwise into long narrow slices (about 15 per eggplant), then cut these crosswise into 2- to 3-inch-long strips. Set aside. Cut the tomatoes into thin wedges, about 12 to a tomato, or chop canned tomatoes into coarse dice. Set aside. Trim the scallions, and reserve the greens. Cut each scallion lengthwise into ribbons, then cut into 1½- to 2-inch lengths. Set aside. Mince the scallion greens; you should have about 2 tablespoons greens. Set aside.

Place a large wok or heavy skillet over high heat. When it is hot, add the oil and swirl to coat the bottom of the pan. Toss in the garlic and ginger and stir-fry briefly. Add the eggplant and stir-fry for a minute; press it against the hot sides of the wok (or bottom of the pan) to try to scorch all surfaces. Add 1 teaspoon of the salt and stir-fry for another minute, then add the tomatoes. Stir-fry for 2 minutes, or until the tomatoes are softened. Add the scallion ribbons and stir-fry to mix. Add the Sichuan pepper and the remaining 1 teaspoon salt and stir-fry for another minute.

Add ½ cup broth and continue to stir-fry until it comes to a boil. Cover and boil hard for 3 minutes, then uncover and stir. Cover again and cook for another 2 minutes. Uncover, stir, and taste the eggplant for doneness. Cook it a little longer if necessary.

Stir in up to ¼ cup more broth if you’d like a more saucy texture. Add the soy sauce and the minced scallion greens, stir, and taste for seasonings. Turn out into a shallow bowl and serve hot.

Serves 4 as a side dish, 2 as a main course with rice and a side dish

A Bai woman in Dali, Yunnan.

Chile-Hot Bright Green Soybeans with Garlic

This attractive dish from the Bai people, who live in western Yunnan province around Lake Er Hai, is traditionally made with fresh fava beans, also known as broad beans, but we prefer to make it with soybeans. We love their bright green color and tender texture, and their availability. We usually buy them already shelled, frozen, in one-pound bags. They’re often labeled edamame, the Japanese name.

1 pound (2 cups) fresh or frozen shelled soybeans (see headnote)

Scant 2 tablespoons peanut oil

2 tablespoons thinly sliced Pickled Red Chiles (page 34) or store-bought pickled chiles, or substitute 5 dried red chiles

5 garlic cloves, thinly sliced

½ teaspoon star anise pieces

1 teaspoon salt

About 1 cup mild chicken broth or pork broth or water

2 teaspoons cornstarch, dissolved in 2 tablespoons cold water (optional)

Rinse the beans under cold water, drain, and set aside.

Heat a wok over high heat. Add the oil and swirl it a little, then add the chiles and garlic and stir-fry for about 30 seconds. Add the soybeans and the star anise and stir-fry for about 1 minute. Add the salt and broth or water and bring to a boil, then reduce the heat and simmer until the beans are very tender, about 7 minutes. (Fresh and frozen take about the same time.)

If you wish, thicken the broth: Give the cornstarch mixture a stir and add it to the wok. Stir-fry for a moment, until the liquid thickens. Turn out and serve.

Serves 4 as a side dish

We don’t know why stem lettuce, usually called celtuce in North America and known as osun in Lhasa, is so widely available there. Perhaps because it grows mostly underground it’s better able to survive the cold than other green vegetables. We do know that this easy stir-fry makes a delicious vegetable side dish, warming on a cold day, with its soupy broth and hint of Sichuan pepper.

Celtuce came to Europe from China in the late 1800s and to the United States in the 1930s. The stem is about 12 inches long, like an elongated broccoli stalk, and it grows underground, with a tuft of leaves at the top.

Prepared celtuce, with the stems peeled or sliced into long fine light green strips, is now sold in markets in Lhasa, and piles of celtuce can also be found in Sichuan and Yunnan food markets. However, it’s very hard to come by in North America unless you grow your own. We suggest that you substitute broccoli stalks, which have a very similar texture once sliced, or use the whiter bottom part of Napa cabbage. (Instructions for both are included; for leafy greens options, see Lhasa-Style Leafy Greens on page 104.)

The vegetable strands are stir-fried, then briefly simmered in broth. Traditionally a little Tsampa (page 180) is used to thicken the broth, but you can use cornstarch dissolved in cold water.

About ½ pound celtuce stems, broccoli stems, or whiter stem ends of Napa cabbage (see headnote and Note)

2 tablespoons peanut oil or canola oil

2 garlic cloves, smashed into chunks

1 shallot or ½ small onion, thinly sliced

1 tablespoon minced ginger

1 teaspoon salt, or to taste

2 tablespoons minced scallion greens (optional)

½ teaspoon ground Sichuan pepper

1 cup Tibetan Bone Broth (page 45) or meat, chicken, or vegetable broth

1 to 2 tablespoons Tsampa (page 180), or 1 tablespoon cornstarch, dissolved in 2 tablespoons cold water

To prepare celtuce or broccoli, peel off the tough outer skin. Cut lengthwise in half and then lengthwise into very thin slices about 4 or 5 inches long, rather like short wide noodles. If you have a Benriner or coarse grater, use it to make long, slender lengthwise slices. You should have about 3 cups. Set aside.

To prepare Napa cabbage, detach the leaves one by one from the stem. Trim off the coarse base, then stack them 4 at a time and cut lengthwise into very narrow strips. Cut the strips crosswise in half. You should have about 4 loosely packed cups; set aside.

Heat a wok over high heat. Add the oil and swirl it around. Toss in the garlic, shallot or onion, and ginger and stir-fry for a minute or so to soften them a little. Toss in the celtuce, broccoli, or Napa and stir-fry briefly, then add the salt and stir-fry for about a minute. Add the scallion greens, if using, and Sichuan pepper and stir, then add the broth and bring to a vigorous boil. Cover and cook for 1 minute. Check for doneness: the vegetable strands should be tender but still firm. If necessary, let boil a little longer, uncovered. Taste for salt and adjust if needed.

If you wish, thicken the broth by adding the tsampa or dissolved cornstarch and stir-fry until the broth thickens, about 15 seconds. Turn out and serve.

Serves 4 as a side dish

TOFU-CELTUCE STIR-FRY: The first day we were in the Dai village of Menghan with our kids (see Dai Spicy Grilled Tofu, page 111), our host, Mei, prepared a very different stem lettuce stir-fry, a Dai version, for lunch. The celtuce strips were seared in a hot wok, then stir-fried with about ½ cup pressed tofu (see Glossary), chopped small, and small chunks of tomato. She didn’t use broth; the only liquid came from the tomato. Flavorings were mild—a little Sichuan pepper, a little dried red chile, and salt.

LHASA-STYLE LEAFY GREENS: The technique used in Lhasa for stem lettuce can also be used for leafy greens, including dandelion greens, pea tendrils, and bok choi. For dandelion greens or tender pea tendrils, begin with 1 pound greens. Wash well, drain, and cut crosswise into 1-inch lengths. Cook as above, but cooking time in the broth will be a little shorter. For bok choi, begin with 1 pound small Shanghai bok choi or regular bok choi. Cut them lengthwise in half, and wash thoroughly in a bowl of water. Follow the cooking directions above, but increase the cooking time after you add the broth to about 4 minutes, covered.

NOTE ON NAPA CABBAGE: Use the whiter stem end of a medium to large Napa cabbage (also known as Chinese cabbage; see Glossary). We often use the leafier pale green parts, cut crosswise, for a stir-fry or for Napa and Red Onion Salad (page 86), then use the stem ends for this Lhasa dish. If starting with a whole cabbage, cut off the bottom 8 inches. Set the leafy top aside for another purpose.

This Yunnanese stir-fry, with its touch of chile and ginger heat, is a simple dish, but one or both of the two main ingredients may be unfamiliar.

Dried tofu sheets are a wonderful pantry staple. They are sold in Chinese groceries (see the Glossary for more). They must be soaked in lukewarm water for 20 minutes or so before using and then can be stir-fried quickly. They absorb flavors beautifully, so they are great in soups and in well-sauced stir-fries like this one.

Jicama (the Mexican name) is often known as yam bean or white tuber in Asia. A pale tan tuber with a crisp white interior, it is native to the Americas but now widely used in China as well as in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand. It stays crunchy when cooked, providing a lovely contrast to the soft texture of the simmered tofu.

1 dried tofu sheet, about 2 ounces (see headnote)

1 small jicama (about 1 pound)

2 tablespoons peanut oil

5 dried red chiles

2 thin slices ginger

1 teaspoon salt, or to taste

½ cup vegetable broth, meat broth, or water

1 to 2 tablespoons soy sauce, or to taste

2 teaspoons cornstarch, dissolved in 1 tablespoon cold water

2 to 3 tablespoons minced scallion greens, chives, or coriander (optional)

Break the tofu sheet (it’s brittle and will shatter when squeezed) into smaller pieces, about an inch or two in size. Place in a bowl, add warm water to cover, and soak for 20 minutes.

Meanwhile, use a sharp knife to peel the tan outer layer off the jicama, cut the jicama into ¼-inch slices, then cut the slices into approximately 1-inch squares. You should have about 4 cups. Set aside.

Heat a wok or large heavy skillet over high heat. Add the oil and swirl it around, then toss in the chiles, ginger, and salt. Add the jicama and stir-fry for about 20 seconds. Lift the softened tofu sheet pieces out of the water with your hand, without squeezing them, and add to the pan. Stir-fry for about a minute. Add the broth or water, bring to a vigorous boil, and cook for about a minute.

Add 1 tablespoon soy sauce to the pan and stir to blend it in. Stir the cornstarch mixture, add to the pan, and stir-fry for 30 seconds or so, until the sauce thickens a little. Taste for seasoning, and adjust if you wish by adding salt or soy sauce.

Turn out into a wide shallow bowl and sprinkle on the minced greens, if using. Serve hot or at room temperature.

Serves 3 to 4 as part of a rice meal

Every year at the busy summer market of Burang, in western Tibet, Nepalis come from the other side of the Himalaya to trade lowland goods for Tibetan wool and salt, and old friends like these two Tibetan men meet again with pleasure.

Tibetan nomads and shepherds, like nomads every-where, have figured out how to be portable. Their wealth is in their herds, yaks and goats primarily. The animals feed on pasture, and they help transport the family belongings from one grazing ground to the next. Nomad “houses” are tents made of wool from their animals. Belongings are minimal but always include a kettle for boiling water and various containers of stored foods. Yet these too are minimal: butter, tea, salt, tsampa, dried cheese. Drying is the primary technique for storing and preserving food, not just cheese, but also meat. In Tibet’s very dry high-altitude climate, drying is quickly done, and it has the advantage for nomadic people of making foods weigh less. No heavy jars of pickles here, just dried or freeze-dried foods.

On our first trip out to Mount Kailas in southwestern Tibet, we came upon a nomad encampment in a striking place. A nearby lake, beautifully framed by low snow-covered hills, was still frozen despite the intense spring sun. The extended family consisted of a couple and their three children, who lived in one tent, and an auntie (we understood her to be the husband’s unmarried older sister), who lived in a nearby tent on her own. Sheep and goats and yaks were dotted all over the bare-looking landscape, moving slowly as they searched for something to eat.

The husband invited us into the family tent, made of brown-black yak wool woven into a thick fabric. We sat down and began to exchange the basic information that always gets aired among strangers: age, marital status, number of children, etc. His wife poured tea into small bowls for us, fresh hot butter tea, and we sat sipping it and looking around at the tent. She reached up, untied a leg of dried lamb or goat that was hanging from the cross-pole, and handed it to her husband. He took out a large knife and cut a thin sliver of meat from the place where some meat had already been sliced off, then passed the leg and the knife to me. I cut off a slice and then passed them both on to Jeffrey. The meat was delicious, not tough as I had expected, and almost sweet, like prosciutto, with a melting texture on the tongue.

After tea, we went over to the auntie’s tent and found her bottle-feeding several young kids, baby goats that were too weak to nurse from their mothers. Before leaving, we gave the family the only thing we had to offer: a color photograph of the Dalai Lama. The wife murmured a prayer as she touched the photo to the top of her head, reverently, then tucked it away in a safe place. When we passed by that way two weeks later, heading back to Lhasa, the family was gone, moved on to another grazing ground. N

He was tall, skinny, and about twenty-five years old, the guy at the “poste restante” in the post office in Kashgar. We’d go in occasionally to check for mail, in those days before e-mail, and there he’d be, awkward and friendly, and very underemployed. He always wanted us to hang around so he could practice his English.

One day when we stopped by, he smiled broadly at us. “Your parents are very well, and your sister is moving to California,” he said to Jeffrey. “What?” we said, not understanding. “Yes, yes,” he said happily, “they wrote you a postcard. Yes, here it is!” He held it up, looking pleased, then handed it to us.

“You read it?” we said.

“Oh yes, I read all the postcards in English. It is good practice for me!”

We said nothing; there was nothing to say, really. So we just thanked him for our mail and headed off down the street.

Not far from the post office a gigantic Mao statue still stood, carved from pale pink stone and the tallest thing around. Was he smiling to himself at the eagerness of the young postal worker?

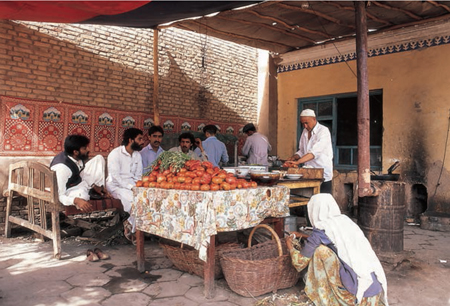

Pakistani traders at a chai khana (informal tea shop and restaurant) in Kashgar sip tea as they wait to be served a lunch of noodles with laghman sauce. The traders travel along the Karakoram Highway from Pakistan to do business, modern versions of Silk Road travelers of centuries past.

Tofu Batons with Hot Sesame Dressing

We first tasted these tofu batons in the Jinghong market in southern Yunnan, sold by Dai women (see page 237). There, as in nearby Thailand to the south, vendors come to the market each day with a vast array of cooked and prepared dishes, ready to be taken home and served as part of lunch or dinner. It’s like “gourmet take-out,” only inexpensive.

As in so many dishes in Dai cooking, there’s chile heat combined with a bit of sour. It’s an easy dish to prepare, and if you’ve never cooked before with tofu sticks, they’re a fun discovery and a good pantry item. When rehydrating them, make sure that they are totally submerged in the soaking water.

3 ounces tofu sticks (4 to 6 sticks) (see Glossary)

1 tablespoon peanut oil

1 teaspoon roasted sesame oil

½ teaspoon chile pepper flakes, or to taste

1 tablespoon rice vinegar, or to taste

2 tablespoons soy sauce, or to taste

½ teaspoon sugar

¼ cup coriander leaves

Bring 2 inches of water to a boil in a medium pot. Add the tofu sticks, breaking them if necessary to make them fit, and use a wooden spoon to push them under the surface of the water. Turn off the heat. Weight down the sticks with a plate that fits inside the pot to keep them submerged. Cover and let sit for 30 minutes.

Remove the plate and drain the tofu well. Cut the sticks into 2-inch lengths, trimming off and discarding any tough bits. Cut the sticks lengthwise in half or into quarters, to make narrow batons. Set aside.

Heat a wok or wide heavy pot over medium-high heat. Add the peanut oil and sesame oil. When the oil is hot, add the chile flakes and tofu batons and stir-fry for 2 minutes, stirring and pressing on the batons to expose them to the hot surface of the pan.

In a small bowl, combine the vinegar, soy sauce, and sugar and whisk well, then pour over the tofu batons. Stir-fry briefly to distribute the flavors, then bring the liquid to a boil. Immediately lower the heat to medium-low, cover, and simmer for 5 minutes.

Turn out into a wide shallow bowl. Taste and add a little more soy or vinegar if you wish. Sprinkle on the coriander leaves, and serve warm or at room temperature.

Serves 4 as a side dish

This grilled tofu always reminds us of our first time traveling in Yunnan as a family. One afternoon, when Dom was nine and Tashi was six years old, we arrived in the town of Menghan and checked into a small family-run guesthouse that another traveler had told us about. The family had two very nice teenage daughters who immediately whisked Dom off to explore the neighborhood. He was delighted.

And then an hour or so passed, and we began to wonder about him. We weren’t particularly worried, just wondering. Suddenly we heard the sound of a motorbike and up pulled the girls, with another friend, and with Dom, all four squeezed on the motorbike. Dom was eating spicy grilled tofu, happy as could be with his new friends.

¾ pound pressed tofu (see Glossary)

2 teaspoons lard (see Note)

1 teaspoon crushed dried red chile or chile pepper flakes

½ teaspoon salt

1 cup Soy-Vinegar Dipping Sauce (page 151)

Prepare a fire in a charcoal grill or preheat a gas grill. Soak 4 thin bamboo skewers in water for 30 minutes.

Cut the tofu into 8 squares, 2 inches by 2 inches. Set aside.

Combine the lard with the chile pepper and salt, and blend together with a fork. The lard should be soft, but not melted. Set aside.

Thread the pressed tofu onto the skewers, putting 2 squares on each skewer and threading them on a diagonal, so they look like diamonds. Lay out on a platter, and use a basting or pastry brush to brush on one side with the flavored lard.

Place brushed side down on the grill and grill for 2 to 3 minutes, until nicely browned. As they grill, brush the top sides of the squares with the remainder of the lard mixture. Turn and grill the second side until nicely browned, another 2 to 3 minutes.

Serve on the skewers, arranged on a plate. Serve with the sauce in condiment bowls, so guests can dip their tofu squares as they wish.

Serves 4 as an appetizer or as part of a meal

NOTE: We learned from the Dai what good flavor a little pork fat can give. We trim the fat off pork roasts or other cuts when we bring them home, then freeze it in a plastic bag, in small quantities, so it’s there when we need to render more lard (see Cooking Oils and Fats in the Glossary for instructions). You can also buy lard from many butchers.

A market scene in the Dai area of southern Yunnan, in the town of Menghan, on the Mekong River.

Kashgar, an old oasis town and important stop on the Silk Road trade routes, lies in the far west of China’s Xinjiang province (in some older books, in fact, the whole of western Xinjiang is called Kashgaria). In 1986 Kashgar was a predominantly Uighur town. Unlike Urumqi, the major city and capital of Xinjiang province, which could be reached by train and already had a majority Han population, Kashgar was much more remote and had retained its Uighur identity. In Kashgar in 1986, central China still felt very far away.

Our plan was to bicycle from Kashgar through the desert and mountains and eventually over the Khunjerab Pass to the Hunza Valley in Pakistan. The road we would take, known as the Karakoram Highway, had been under construction for almost twenty years, a joint project between China and Pakistan, and it was scheduled to open to foreign travelers in May 1986.

We’d come a long way to get here. We’d brought bicycles, tools, a tent, and sleeping bags, as well as a month’s supply of freeze-dried food to Lhasa, where we’d been based for several months. From Lhasa, with the help of three kind friends met there, we’d traveled overland to Kashgar with all our gear.

That trip took eleven days. First we traveled by bus for two days north from Lhasa to Golmud, and from there it was another long day’s bus ride northwest to the town of Dunhuang. Then we had a two-day train ride to Turpan, another day and night of train to Korla, and three more days by bus to Kashgar. This was the modern version of traveling the Silk Road. We weren’t traveling with camels or donkeys, as in days of old, but the trip was still a long one, and we were happy to arrive.

We were staying at the Chini Bagh Hotel, which had been the British consulate from about 1890 to 1947. We’d read about the Chini Bagh in books by travelers who had stayed there, such as Ella Maillart (see “Ella,” page 70) and Peter Fleming, and also in memoirs by men who had been posted there as consuls, including C. P. Skrine and the famous climber Eric Shipton (see Bibliography). The building had seen better days, but it was still full of charm. The other people staying there were mostly businessmen and traders from Pakistan who were seizing the opportunity to explore China’s then-new experiment with free enterprise.

In Kashgar we ate as if we might never be able to eat again. There were incredible flatbreads (nan) baked fresh in tandoor ovens several times a day. There were melons from the oasis, watermelons and Hami melons, and sweet perfumed melons we’d never tasted before. There were many kinds of lamb kebabs and rich intricate pulaos. But almost best of all were the homemade noodles, hand-stretched noodles (see “Uighur Flung Noodles,” page 152), one of the food world’s most amazing cooking feats.

Every evening we would have a plate of noodles with laghman sauce (see page 135), fresh tomatoes stir-fried with green peppers, a little lamb, and slices of onion. Simple, but beyond delicious. We’d drink a beer or two and watch donkey carts pass on the street in front of us. Sometimes we’d even have a second plate of noodles. And all this in the desert air, in an ancient Silk Road town.

Then one day it was time to leave. We loaded up our panniers and set out on our bicycles across the desert. Like so many travelers before us, we were heading for the snow-capped mountains we could see, like a mirage, far away on the western horizon: the Pamirs, and beyond them the Karakoram.

A small horse caravan in the Pamirs, below Mount Kongur.

Town square in Yuanyang, with several Yi women and morning fog.

These grilled potatoes are part of a typical Yi noodle stand (see Yi Market Noodles, page 126), and a common street food in the Hani areas of southeastern Yunnan. They are just delicious on their own, but they also pair well with grilled meat and a salad. We often make them when we’re cooking beef, pork, or chicken on the grill; then all that’s left to do is prepare a salad or green vegetable to serve alongside.

The potatoes are first boiled until almost cooked through, then peeled and cut into chunks. The chunks go on the grill, and soon they have a wonderful grilled flavor and chewy skin. They are not seasoned or oiled before grilling, but once cooked, there’s an array of flavors that can accompany them, from coarse salt to chile paste to chopped cucumbers. In the end, we find them most delectable eaten plain with salt. Allow about half a pound of potatoes per person.

Large potatoes, such as Yukon Gold, preferably local and organic

Coarse salt

Tribal Pepper-Salt (page 36) or ground dry-roasted Sichuan pepper (optional)

Soy-Vinegar Dipping Sauce (page 151; optional)

Place the potatoes in a large pot of water and bring to a boil. Boil until the potatoes are barely cooked through. Drain and let cool. (The potatoes can be boiled as long as a day ahead; once cooled, store covered in the refrigerator.)

Prepare a charcoal grill or preheat a gas grill, with the rack about 5 inches above the coals or flame.

Strip the peels off the potatoes and cut them into l½-inch chunks. The more cut surfaces they have, the more taste of the grill they’ll absorb during cooking. Place them on the grill (either directly on the grate or in a grilling box) and grill, turning occasionally, until golden on all sides; resist the urge to season them while they cook.

Serve plain, accompanied by coarse salt and, if you like, a choice of seasonings put out in small bowls.

This deep-fried street-food snack comes from Lhasa. The potatoes are peeled, sliced, and slipped into hot oil. When they are lifted out several minutes later, they are golden and crisp on the outside and tender in the center. The vendor dusts them with a little cayenne, if you want, and a sprinkling of salt.

I wanted to see if making Lhasa-style fried potatoes was as easy as all the vendors there made it look. The first time I tried it, I was working on a wood stove, so the temperature varied, and I had only a small wok for deep-frying. We had a crowd for supper, but the meal itself would not be ready for another hour. I hoped the fried potatoes would fill the appetizer gap and keep everyone happy.

They did: the slices cooked to a beautiful golden brown, it was easy to tell when they were ready, and I found deep-frying them a pleasure. The only complication was deciding what flavorings to add: salt is a given, but options include chopped fresh mint (a nontraditional idea inspired by the mint in our garden; ground roasted Sichuan pepper; cayenne, which is quite common in Lhasa; and/or a pepper-salt.

These are best eaten hot and fresh, as an appetizer or a snack. We’ve found that when we fry them, some people like the thinner, crispier slices, while others prefer the tender, paler, thicker ones. So when you slice your potatoes, remember that you don’t have to cut them to the exact same thickness—variation means your guests have choices, and that’s a great thing.

About 3 pounds Yukon Gold or other firm potatoes, peeled

Peanut oil for deep-frying (2 to 4 cups)

Coarse salt

OPTIONAL TOPPINGS

Cayenne pepper or Tribal Pepper-Salt (page 36)

Ground dry-roasted Sichuan pepper

About 1 cup mint leaves, coarsely chopped

Cut the potatoes into ¼-inch slices and set aside in a large bowl. Put out a slotted spoon or a long-handled mesh skimmer. You may also want to use a long-handled spatula. Have a shallow wooden or ceramic bowl ready for serving the potatoes.

Place a large wok or deep heavy pot on the stovetop; make sure it is stable. (Or use a deep fryer.) Pour 2 inches of oil into the wok or pot and heat over medium-high heat. You want the oil to be between 350° and 375°F; use a deep-fry thermometer to monitor the temperature. Or test it in the following way: Slide a slice of potato into the oil. It should sink and fizz and then slowly start to rise to the surface. If it bobs right up and starts to brown very quickly, the oil is too hot—lower the heat slightly. If it sinks and rests on the bottom for a while lethargically, the oil is not yet hot enough.

When the oil is at temperature, slide in a handful of potato slices, without crowding; there should not be so many that they are above the level of the oil. Use a spatula or the slotted spoon or skimmer to move the potatoes around; separate any slices that are sticking together. After about a minute, move them again and gently turn them over, to ensure all sides are cooked in the hot oil bubbling up from the bottom. After another minute or two, you should see them browning.

Lift one slice out with a slotted spoon, and transfer it to a plate. Cut it and taste it, being careful not to burn yourself. If the potato is tender all the way through, use the slotted spoon or skimmer to lift the rest of the potato slices out of the oil, pausing for a moment to let excess oil drain off them, then transfer them to the serving bowl.

Repeat with the remaining potato slices, handful by handful. You’ll quickly learn to judge when the potatoes are done the way you like them. Once you have cooked several batches, sprinkle on salt and any other toppings you wish and put them out for your guests. Repeat until all the slices are cooked and served (see Note).

Serves 6 as an appetizer with drinks or as a snack

NOTE ON STORING OIL: Set the wok or pot of oil aside in an out-of-the-way place to cool. Pour the cool oil through a fine-mesh strainer into a clean, dry jar. Seal with a tight-fitting lid and store in the refrigerator. You can reuse the oil several times for deep-frying or stir-frying. Once it gets dark or has a strong smell, discard it.

A stack of flatbreads and a Uighur man grilling kebabs at the evening street market in Altai, in northern Xinjiang.

Hui Vegetable Hot Pot

The cliché image of Central Asian food is of kebabs or other grilled meat, perhaps with some dairy products on the side. But, like many clichés, the image needs adjusting. In Xining, an old trade-route town just east of the Koko Nor with a large Hui population, I came upon a brilliant vegetarian hot pot.

It was late on a Friday afternoon. Men were just coming out of the mosque after prayers, and the markets were lively. There were skewers of lamb’s liver and tongue grilling over charcoal, tended by bearded men; there were stacks of flatbreads and vegetables of all kinds; there were noodle makers cutting and stretching batches of pale smooth dough; and in several stalls, frequented mostly by women or families, there was this Hui version of hot pot.

I couldn’t resist. I went in and found a seat, but then I had real trouble deciding what to order. There were skewers of raw vegetables of all sorts: four different types of mushrooms, several kinds of lettuce leaves, eggplant slices, potato slices, zucchini, mustard greens, pea tendrils, pressed tofu slices, and more. You chose the skewers you wanted and they were cooked to order and served to you with a bowl of noodles and hot broth.

The great thing about this approach is that because there is only one kind of vegetable on each skewer, they can be cooked to a beautifully exact doneness, with no compromise. The vendor took the skewers I’d chosen (oyster mushrooms, zucchini, a romaine-like lettuce, and mustard greens) and plunged them into the vat of boiling broth. He used a mesh colander to scoop up some parboiled noodles and placed them in hot water to heat up and soften. They came out first, steaming and soft, and were tipped into a large bowl. As each skewer of vegetables was cooked, it was lifted out and laid across the bowl. Finally he poured hot broth onto the noodles and sprinkled on some chopped Chinese celery and scallion greens.

On the table was a cruet of black rice vinegar, along with small dishes of soy sauce, chile paste, and a vinegar-cucumber sauce. I took a sip of the broth with my spoon, then added a little vinegar and a little soy to it. I made up a small blend in the condiment dish they gave me: a dab of chile paste stirred into the dark vinegar. Then I used my chopsticks to slide a zucchini slice off its skewer and dip it into the chile-paste blend. Delicious! The noodles had great bite, the mushrooms were poached to perfection, and the lettuce was too. Altogether it was a wonderful meal.

To reproduce this style of hot pot, all you need is a choice of vegetables and wooden skewers (30 or so for 6 people) to thread them on; some noodles, homemade, or store-bought fettuccine or egg noodles; a broth; a large pot; and some condiments. Serve as a main course, perhaps followed by a grill such as Uighur Lamb Kebabs (page 260) or Dai Grilled Fish (page 222), with cooling slices of sweet melon to finish the meal.

1½ to 2 pounds Amdo Noodle Squares (page 128), long Tibetan noodles (see page 144); or Tuvan noodles (see page 246) or 1 pound store-bought fettuccine or egg noodles

2 tablespoons peanut oil or vegetable oil

VEGETABLES

3 medium zucchini, cut into ¼-inch slices

20 to 30 leaves of leaf lettuce

About 6 leaves Napa cabbage, cut crosswise into 2-inch-wide strips

1 pound mixed mushrooms (such as oyster and white), cut in half if large

2 cups large cauliflower florets and/or large broccoli florets

2 cups mustard greens or bok choi leaves

About 1 cup Jinjiang (black rice) vinegar

Soy sauce

½ cup Guizhou Chile Paste (page 35) or store-bought chile paste

2 cups Cucumber-Vinegar Sauce (page 83)

8 to 10 cups Hui Vegetarian Broth (page 48) or other vegetable broth or light chicken stock

Bring a large pot of water to a boil. Add the noodles or pasta and cook until barely cooked through and still firm. Drain and transfer to a bowl. Drizzle with the oil and toss to coat. Set aside.

Prepare the skewers, filling them only one-half full, leaving both ends clear (see photo, page 116). Thread 3 to 5 zucchini slices each on 6 to 8 skewers. Thread 6 skewers with the lettuce leaves, piercing each leaf several times so it is secure. Thread 6 skewers with the Napa cabbage. Thread 6 skewers with 3 or 4 mushrooms each. Thread 6 skewers with 3 or 4 cauliflower or broccoli florets each. Thread 6 skewers with mustard greens or bok choi leaves.

Put out the condiments in bowls, as well as two small condiment bowls for each guest, so they can serve themselves and make their own combinations of dipping sauces.

Bring the broth to a rolling boil in a large pot. Place the vegetable skewers into the broth in order of firmness, so, for example, the cauliflower and broccoli go in well ahead of the lettuce.

Meanwhile, divide the noodles among six soup bowls.

As the vegetables on each skewer are done, lift the skewer out of the broth and lay it on a platter. Once all the skewers are out, ladle the hot broth over the noodles in each bowl and set out the bowls. Place the platter in the center of the table and let guests help themselves to skewers of vegetables. They can use chopsticks to slide cooked vegetables off the skewers and into their soup as they wish. Invite them to make a blend of condiments in their condiment bowls for dipping or for pouring into their soup.

Serves 6 as a main course

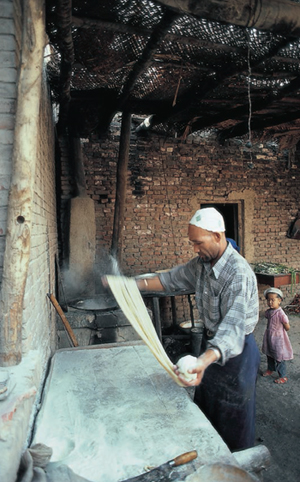

On our trip along the Silk Road (see “Kashgar, 1986,”page 112), we were invited to a Uighur home in Aksu, a small oasis town at the time that has now grown into a bustling small city. The family were bakers and noodle-makers. Here, in the courtyard behind their clay-brick house, the father stretches noodles in the classic Uighur style while his young daughter watches. Notice the trellises overhead, which less than a month later (we were there in late May) would be lush with grape vines, giving welcome shade from the intense desert sun.

The first and only time I tasted these chickpea fritters in China was in a tiny restaurant (using the word “restaurant” makes it sound bigger than it was) just off the main intersection in the town of Turpan (see “Turpan Depression,” page 200) in Xinjiang. I’d been invited to the restaurant by two fellow travelers, Stephane and Thanya, whom I had met a few days before. We had rented a car together to go on a morning’s outing, and for lunch we ended up in this little place they’d discovered earlier. The fritters were served with a hot chile pepper paste; like falafel, they were moist and soft rather than crunchy, and they were beautiful with their strands of orange carrot.

As remarkable a pleasure as the restaurant was, Stephane and Thanya were even more remarkable. They had been on the road for three years, teaching English in Sichuan, Taiwan, and Inner Mongolia. It was through their excellent recommendations that Naomi ended up spending time in Hailar (see “Mongolia out of Season,” page 244).

Stephane and Thanya are from Timmins, Ontario. They’re both bilingual in French and English, as well as working toward fluency in Mandarin. As travelers, they were immediately friendly and open, and they were unwaveringly appreciative of the opportunity to live, work, and travel in China. They were the opposite of jaded, and it was so refreshing to be with them. They are also among the most adventurous eaters—on the road—that I have ever known, always looking for something new to try. I felt very lucky to meet them.

For the next few months, we corresponded by e-mail. They journeyed into northern Pakistan, got caught in the middle of a local war in Gilgit, and then traveled all around the coast of India before finally returning home.

Serve the Fritters with Guizhou Chile Paste (page 35) or Bright Red Chile Paste (page 18) or a store-bought chile paste; Jinjiang (black rice) vinegar (see Glossary) or Soy-Vinegar Dipping Sauce (page 151); and/or a chutney or relish, homemade (see Index) or store-bought.

1 cup dried chickpeas

1 tablespoon water

1 teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

2 cups coarsely grated carrots (about ¾ pound)

Peanut oil for deep-frying (2 cups)

Wash the chickpeas and soak overnight, covered, in 4 cups water.

Drain the chickpeas and transfer to a food processor. Add the 1 tablespoon water, the salt, and pepper and process until the chickpeas are finely ground. Transfer to a bowl, add the carrots, and mix well.

Scoop up 2 tablespoons of the mixture, squeeze it together in your hand, and shape it into a ball between your palms. It will be about the size of a golf ball. Flatten it into a disk about 2 inches across and set aside on the counter near your stovetop or on a lightly floured baking sheet. Repeat with the remaining mixture. You will have about 14 disks.

Set out a platter or two plates lined with paper towels or brown paper beside your stovetop. Also put out a slotted spoon or mesh skimmer. Place a large wok or large deep wide pot on your stovetop; make sure that the wok or pot is stable. (Or use a deep-fryer.) Pour in 2 inches of oil and heat the oil over medium-high heat. To test the temperature of the oil, hold a wooden chopstick vertically in the oil, with the end touching the bottom of the pot. If bubbles come bubbling up along the chopstick, the oil is at temperature. The oil should not be smoking; if it is, turn the heat down slightly and wait a moment for it to cool, then test again. (A deep-fry thermometer should read 325° to 350°F.)

Slide 3 or 4 chickpea disks into the oil and cook for 2½ to 3 minutes, using the slotted spoon or mesh skimmer to turn them over partway through, until they are nicely browned on both sides. Lift the fritters from the oil, pausing to let excess oil drain off them, and place on the paper towels or brown paper. Repeat until all the fritters are cooked.

Transfer the fritters to a serving plate. Serve hot or warm, with the condiments of your choice.

Makes about 14 fritters; serves 4 to 6 as an appetizer or as a side dish

The Dong live mostly in eastern Guizhou and western Guangxi. They number about three million. Like the Dai (see page 237), the Dong are one of many branches of the Tai-Kadai linguistic and ethnographic family, which also includes Thai and Lao. Their languages are distinct but have common roots.

Different villages in the Dong area have distinctive clothing and embroidery designs, so that villagers can distinguish at a quick glance where a stranger is from. Dong women are famed for their textiles, not just woven cotton and hemp, but also the technique of indigo dying—the fabric is pounded so that it absorbs a dark, rich color, almost purple-black, and has a sheen to it. The women also do very fine embroidery, some groups more than others, and are rarely without handwork in their spare time.

The Dong are known for two types of special timber-frame structures, drum towers and covered bridges. The drum towers are pagoda-like with an open area at the bottom, where the villagers can sit and visit and children can play, protected from the sun and rain, beneath a multilayered roof that tapers to a point. The whole structure is timber frame, a complex set of crosspieces of decreasing size. Similarly, the covered bridges are roofed timber-frame structures with railings but no walls. They may have been developed as a practical way to have a place to sit and to work sheltered from the wind, rain, and hot sun, but they’ve evolved into extraordinary structures, less common than the towers (not every village has a bridge).

Older women and men can be found at any hour in the shelter of the neighborhood tower or covered bridge, chatting, playing chess, embroidering, or keeping an eye on small children. The drum towers also shelter the village collection of lusheng, instruments made of parallel lengths of bamboo that look like large panpipes and sound like very reedy bagpipes.

The Dong areas of Guizhou and Guangxi have plentiful rains most years, and rice, the staple crop, is grown on steeply terraced hillsides, with sophisticated stone barriers and small waterways for managing water flow. Though sticky rice seems to be a cultural marker for the Dong, as it is for all Tai peoples that we know of, regular aromatic rice is also grown. On the steepest hillsides are carefully tended groves of the fir trees the Dong use to build their timber-frame houses, towers, and bridges.

Rice growing demands community cooperation and a lot of hard work, especially in hilly landscapes. Harvesttime is late September to late October. The sheaves of rice are hung on distinctive latticed scaffolding to dry, then carried home and hung under the eaves, like a hanging golden curtain. Some households also have sheaves of millet drying in the same way. By early November, there are chiles, some medium-hot (cayennes) and some sweet-hot (certain Turkish or Spanish chiles), drying in the sun alongside soybeans, chopped greens, and mustard seeds. There’s a delicious tradition of pickled greens, and meat and fish are often pickled too.

An aerial view of Zhaoxing village, taken from up on one of the steep hillsides that rim the town. At the lower left is one of the town’s covered bridges, airy yet sheltering, and in the upper right is a drum tower (there are five in Zhaoxing, more than in any other Dong village). The houses are tall wood structures built of fir, with no nails used in their post-and-beam construction. A new house is being erected in the upper left. Recently, tourism has brought more prosperity to the town; notice the occasional satellite dish on the rooftops.

Also in Zhaoxing, a grandmother, her hair bound up in the distinctive black-and-white handwoven scarf worn by older Dong women in this part of Guizhou, sits at her loom weaving. The loom is inside her house, by an opening that gives her natural light to work in and a good view of people passing by on the footpath outside.