It’s the dawn of a new millennium and London is steady in its rise as a global city. With the arrival of a new Underground route – the Jubilee Line – the development of Canary Wharf is finally accelerating. Meanwhile, in the City, attitudes towards skyscrapers have relaxed, with 30 St Mary Axe leading the way. An increased awareness of climate change is forcing planners to demand energy-saving building techniques and renewable energy supplies, prompting a ‘green architecture’ movement that takes efficiency to its heart. But the deregulation of the banking industry soon leads to global economic crisis, hitting London particularly hard. The government bailout of failing banks is followed by harsh cuts in welfare for the majority; the gap between rich and poor is stark, and increasingly obvious.

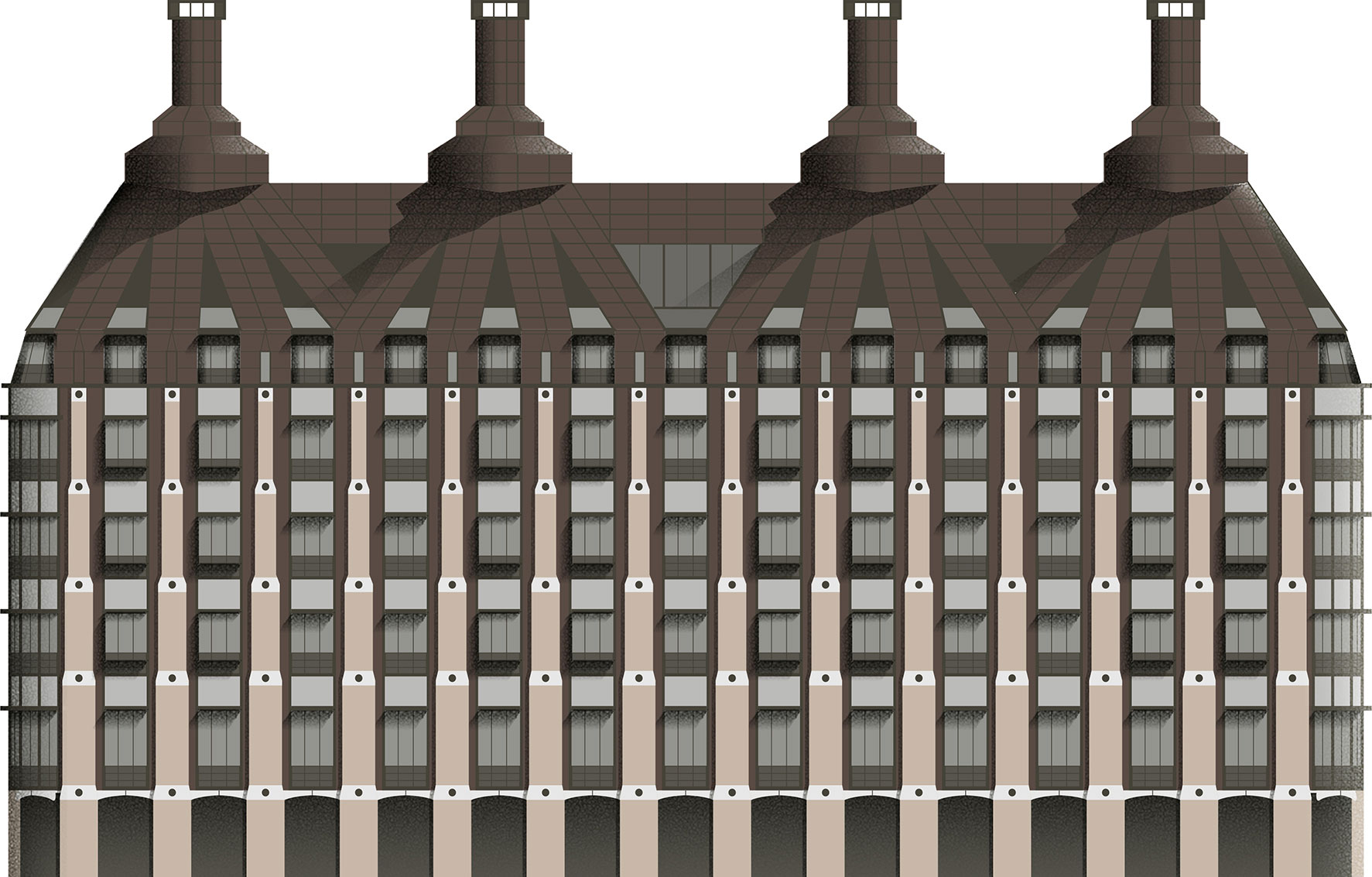

Portcullis House (101) in Westminster is an offshoot of the Palace of Westminster, the home of the British government. Since the palace is a protected UNESCO World Heritage Site, the extension had to keep its distance and so was built across the street. It hosts offices and facilities for more than 200 members of parliament, and is connected to the palace by an underground tunnel – so employees don’t have to run across the busy road above. Hopkins Architects designed a building that is traditional in concept, but uses the latest materials and technology.

101 Portcullis House

Hopkins Architects

2001

2001  SW1A 2JR

SW1A 2JR

It forms a classical square block with a protected courtyard in the middle. The bomb-proof building features steep sloping roofs and tall chimney structures (part of a system of natural ventilation), creating a profile not dissimilar to its centuries-old neighbour. Part of the development was the new Westminster Underground Station, which was built seven floors below ground – the deepest excavation ever made in central London. The foundations of the nearby Big Ben had to be strengthened, but it still moved a couple of centimetres as a result.

Parliament Emblem

The portcullis has a historic connection with the Houses of Parliament, and aside from giving its name to the new building, it is also used as the Parliament’s emblem.

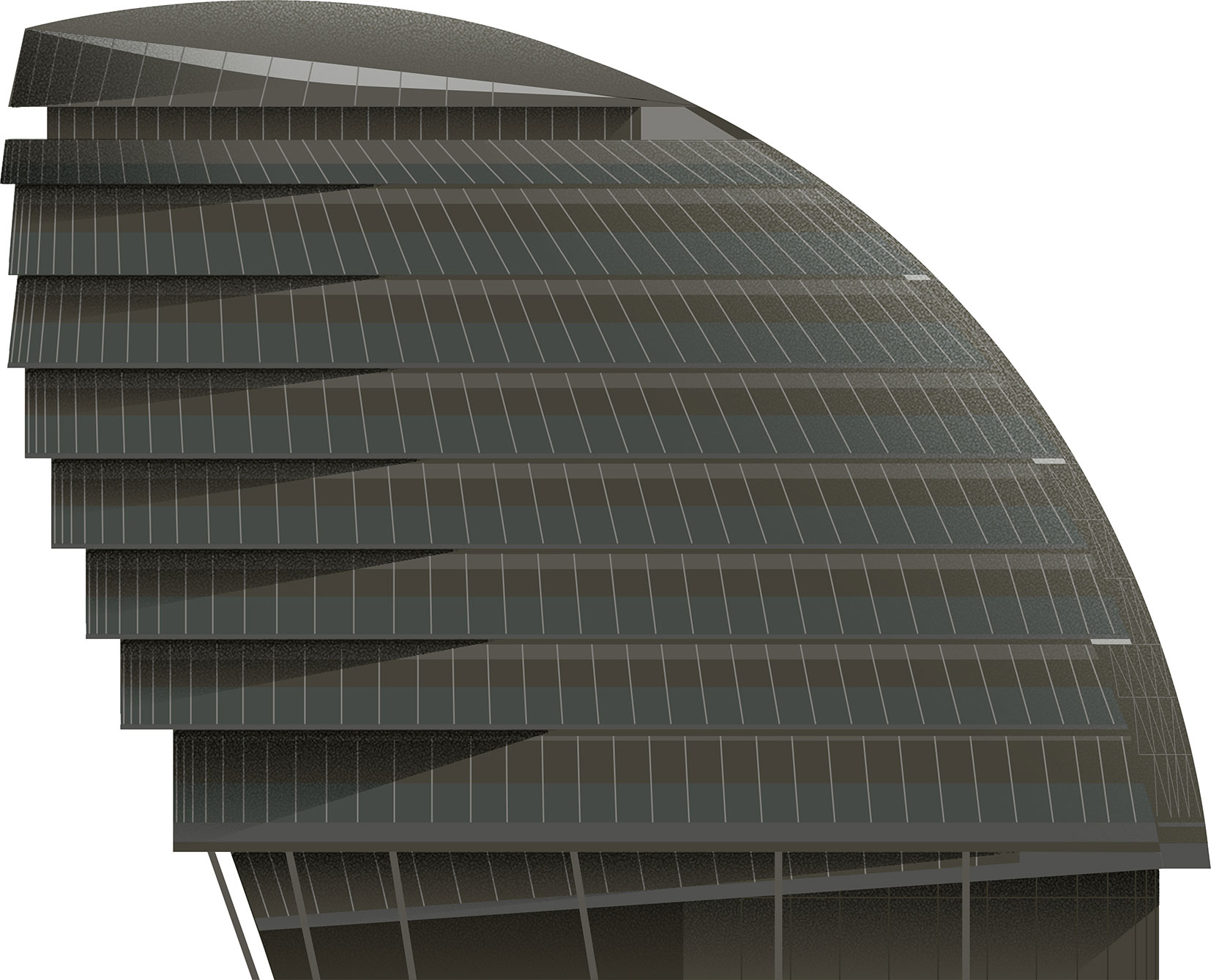

City Hall (102) – rather harshly nicknamed the Glass Testicle – is home to the relaunched and rebranded London Council. Now named the Greater London Authority (GLA), the organisation is smarter, smaller and more streamlined – much like the building itself. Perhaps symbolically, the structure is privately owned and only rented by the GLA, marking a new era of outsourcing and the much more limited power of the council – once the biggest landlord in the world, with the largest architecture department on the planet.

102 City Hall

Foster + Partners

2002

2002  SE1 2AA

SE1 2AA

City Hall was designed by Ken Shuttleworth of Foster + Partners, and centred on the idea of a ‘non-polluting’ public building. Computer modelling – brand new technology at the time – enabled architects to shape buildings into previously impossible forms. But City Hall’s shape wasn’t designed just for show. It minimises areas exposed to the sun; as is the case with most glass office buildings, too much direct sunlight creates excessive levels of heat and the subsequent need for energy hungry air conditioning units. To combat the issue further, cold groundwater is pumped around the building to cool it down.

All of this worked on paper, but unfortunately the reality proved different. Disappointingly, the building has only an Energy Performance Certificate rating of ‘D’ (‘A’ is the best and ‘G’ the worst), the same as Portcullis House (101). This is due in part to the rise in the number of people working inside, an inevitable outcome of the growing council. Building managers also had to figure out how to use the system properly, which proved time consuming. The impressive staircase, spiralling 500 metres through the building, is reminiscent of Foster + Partner’s parallel work – the Reichstag in Berlin, where people can see the government at work from a similar ramp. Unfortunately, the ramp is closed to the public most of the time due to security concerns.

Before Tate Modern (103) became one of the ‘coolest art galleries in the world’, it was warming up the atmosphere as Bankside Power Station (053). The large complex closed its gates in 1981, after high oil prices made it too expensive to run. The power station stood empty for thirteen long years before the Tate Gallery announced its plans to turn the space into a new art museum. Swiss architects Herzog and de Meuron were tasked with giving the building a new lease of life.

103 Tate Modern

Herzog and de Meuron

2000

2000  SE1 9TG

SE1 9TG

Instead of large design gestures, which one would expect from a modern art gallery, their work largely consisted of clearing up the structure and adding some modest additions. At the heart of the gallery stands the Turbine Hall, a breath-taking space of giant proportions that is regularly filled with similarly sized art commissions. The huge visitor numbers soon proved lifts and facilities too small, and so the gallery began plans for an extension (119).

MD900 Explorer

The new helicopter of the Whitechapel-based London Air Ambulance doesn’t use a tail rotor, which helps it to land in the crowded streets of the capital. A second machine was bought with the help of charity donations in 2015.

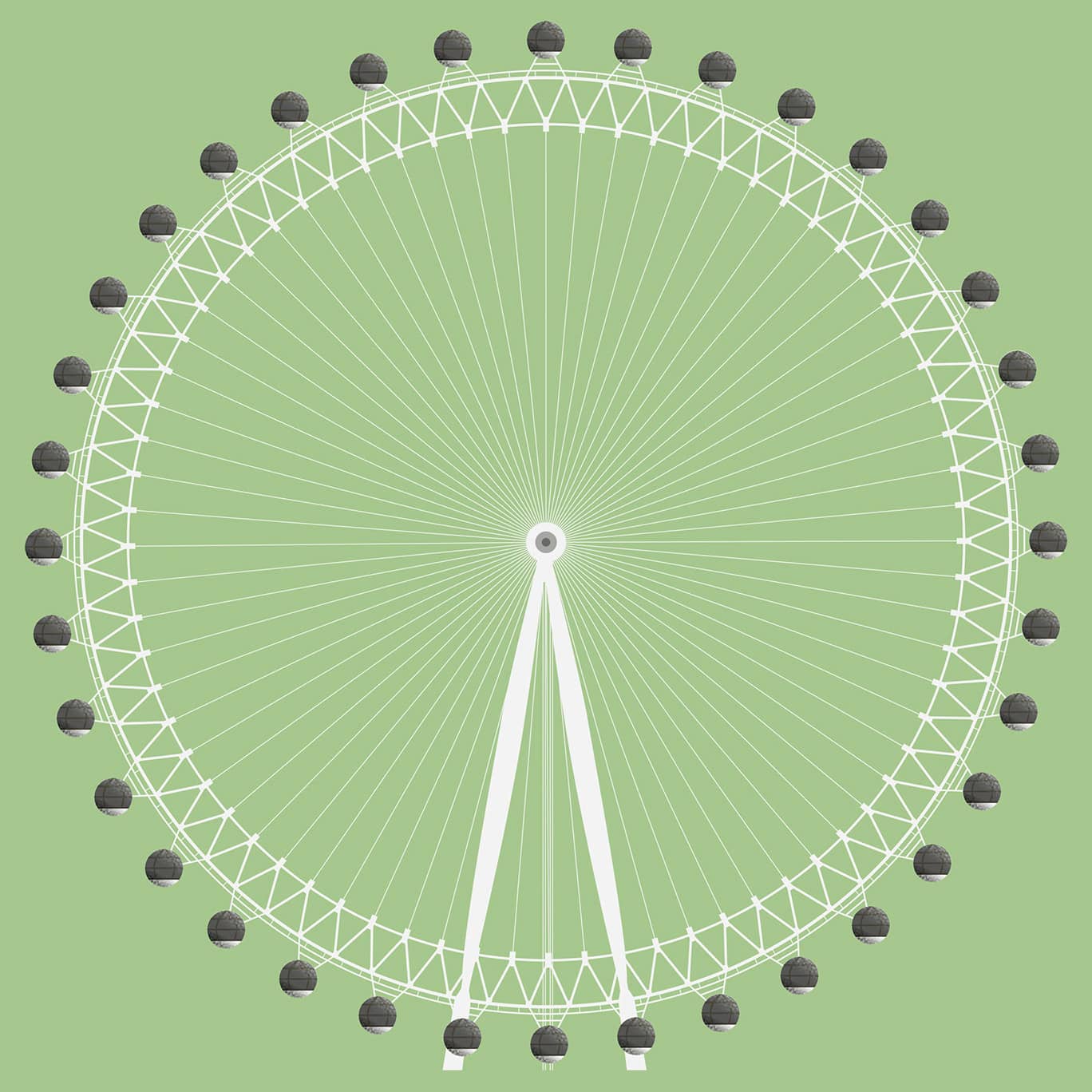

The London Eye (104), originally called the Millennium Wheel, was one of the so-called ‘Millennium Projects’ that sprung up at the end of the twentieth century (see Millennium Dome (100)). The initial idea was formed in 1993, but construction didn’t start until January 1999. The opening was scheduled for New Year’s Eve, and so construction became a race against time.

104 London Eye

Julia Barfield and David Marks

2000

2000  SE1 7PB

SE1 7PB  158M

158M

Snapped cables, occupation by protesters and unusually high tides, which left no space for barges to pass under the bridges, all caused delays. All hope for completing on time was lost just one day before the celebrations, when one of the thirty-two pods failed a safety check. The opening had to be postponed until March 2000, but it was all worth it in the end. Incredibly, 6 million people took it for a spin in the first six months alone, breaking all predictions.

The architects, husband and wife team David Marks and Julia Barfield, originally received permission for a structure lasting only five years, after which it would have to be taken down. But its unexpected success means the wheel is now embedded in the London skyline, even making it onto seat covers (moquettes) on the Underground. Copycat designs have seen Ferris wheels pop up in cities all around the world.

Mercedes-Benz O530G ‘Bendy Bus’ Citaro

These high-capacity articulated buses were introduced in 2002. Their three doors sped up boarding, but gave them the nickname the ‘free bus’, as many people didn’t bother to tap their Oyster cards once on board. The buses also proved dangerous to cyclists and Boris Johnson promised their replacement as part of his mayor campaign. He succeeded.

Norman Foster is one of the few living architects to have become a household name. His buildings, many of which were produced in this period, have helped shape London as a modern metropolis. He had a modest upbringing in industrial Manchester, where he started working as a clerk at the town hall aged just sixteen. After undertaking national service with the RAF, he decided to study architecture at Manchester University. A model student, he won a fellowship at the Yale School of Architecture in the US. There he met Richard Rogers – they later formed Team 4 together with Wendy Chessman and Su Brumwell. The small but influential partnership lasted a couple of years, but later split into the separate Foster and Rogers practices we all know today.

HSBC Tower (105), also known as 8 Canada Square, is a showcase of a new generation of office buildings, and arguably the reason why Canary Wharf (after all those years) became so attractive to giant business corporations. Foster had designed the bank’s monumental (and expensive) Hong Kong headquarters in the 1980s – this time he was tasked with creating a cheaper and more easily adaptable structure. A new system of construction, which came on the sails of American investors flocking to the City after the Big Bang, dictated that the architect design only the shell and core of the building.

105 HSBC Tower

Foster + Partners

2002

2002  E14 5HQ

E14 5HQ  200M

200M

Tenants were then free to fit it out for use as required. The role of Foster + Partners was in some ways very limited. The sleek tower, softened by rounded corners, is as flexible (or without character) as possible. Just unpeel the bank’s logo on the top and someone else is free to move in. The tower is flanked by two siblings – 33 Canada Square and One Canada Square (087). Both have exactly the same floor space and height (if you dismiss the pyramid on the latter). This shows the difference between Canary Wharf and the City, where every site is in the latter distinctive and has its own characteristic requirements. HSBC sold the building just four years after moving in, then bought it again five years later, only to sell it once more. This shrewd property juggling resulted in huge profits for the bank.

Eurocopter EC145

These Metropolitan Police helicopters hovering over London are now as common as pigeons. Equipped with night vision and heat cameras, they operate twenty-four hours a day.

30 St Mary Axe (106), better known as the Gherkin, is without a doubt the most recognisable twenty-first-century building in London. Its story is long and painful, although not without a happy ending. It started with a terrorist attack in 1993, when the IRA set off a truck bomb in the heart of the City. Many buildings were damaged, including the NatWest Tower (077). But the listed Baltic Exchange was hardest hit and was put up for redevelopment. Foster produced a design for a 386-metre-tall Millennium Tower, but it was way too high (the Shard (117) is seventy metres lower) and was rejected by planners. In response, Foster’s practice developed a new, organically shaped and much shorter design, in cooperation with the city planners. Surprisingly, the planners recommended building higher than originally intended, to improve the building’s proportions.

106 30 St Mary Axe

Foster + Partners

2004

2004  EC3A 8BF

EC3A 8BF  180M

180M

The tower is wrapped in an elegant diagonal steel structure, which removes the need for any internal supports. The structure rotates by five degrees on every floor, creating an elegant façade with a twist. The Gherkin quickly gained global notoriety and often appears in ‘establishing shots’ of London-based films – something many architects dream of (although perhaps not the architects of Thamesmead, after Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange). Similarly to City Hall (102), the Gherkin was (and still is) promoted as a triumph of green, sustainable architecture. But the complex system of natural ventilation that was supposed to cut the energy consumption was abandoned when it became clear the tenants preferred machine air conditioning. On top of that, one of its architects, Ken Shuttleworth, turned against it just a few years later, noting that the fully glazed façade is expensive and plays havoc with interior temperature control.

Thames Clippers

With its roads jam-packed, London looked back on its natural artery, the River Thames. New lines of fast boats now ferry commuters from suburbs on the river to the city centre.

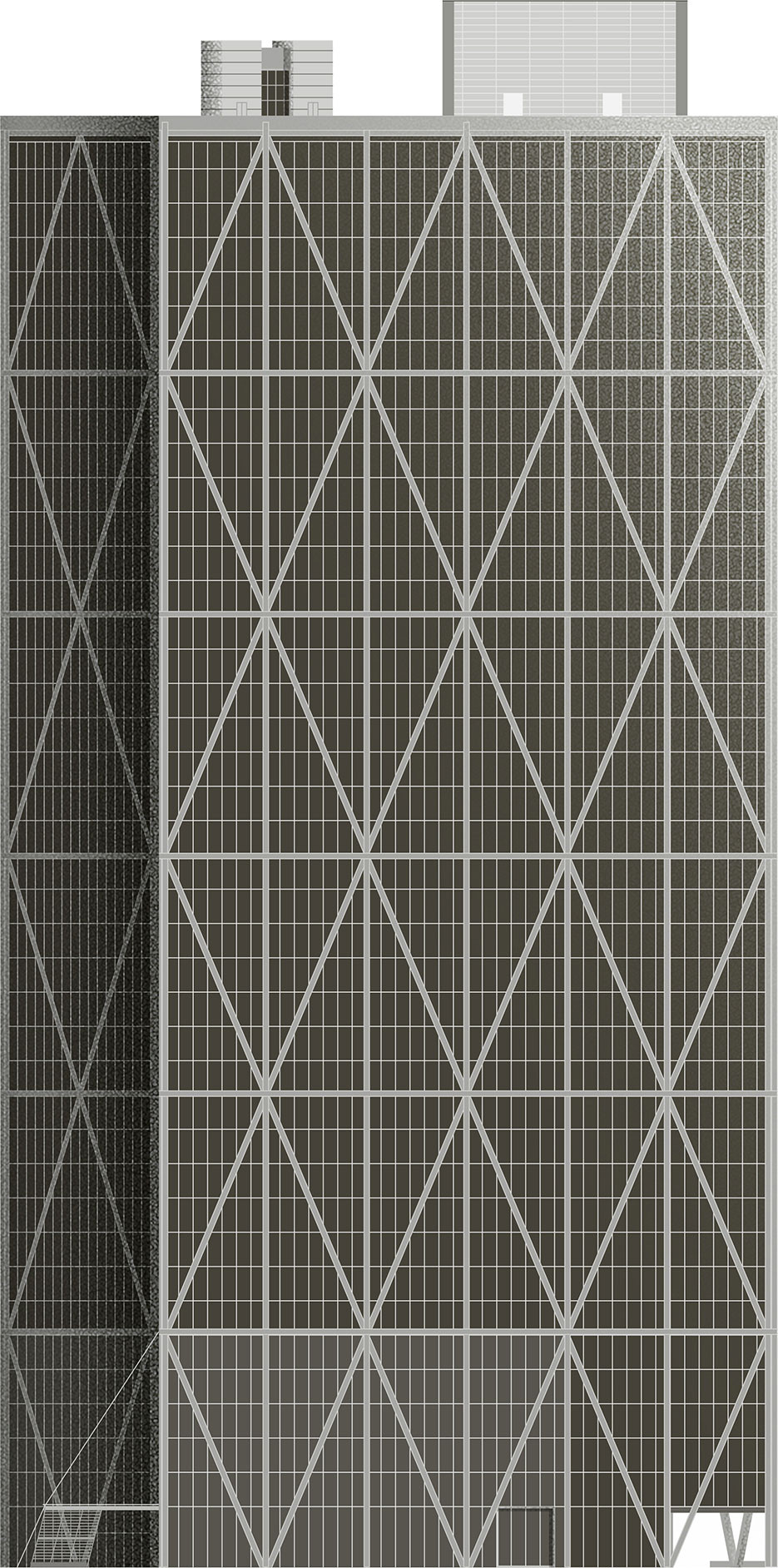

The increasing number of towers springing up in London during this period might suggest that all height restrictions had been forgotten, but the case of Broadgate Tower (107) reminds us that this wasn’t the case. The law protecting views of St Paul’s Cathedral from certain areas was still in place, most notably in the preservation of the sight-line from King Henry’s Mound in Richmond Park, nearly ten miles away. This visual corridor doesn’t end at the cathedral, but continues for another mile and a half behind it and so falls directly over a part of the Broadgate site. This limited the maximum height of the development. Instead of designing one large, low building, the Chicago office of SOM decided to split the site in two. A skyscraper, tucked into the ‘unprotected’ corner of the site, is joined by a lower building on the other side. The tower hovers above a busy railway track, as does the nearby Exchange House (089). It adopts the same bridge structure for spanning the railway, but in a less apparent fashion.

107 Broadgate Tower

SOM

2009

2009  EC2A 2EW

EC2A 2EW  161M

161M

Structural steel supports criss-cross the façade, holding the building together, and at the base a giant steel A-frame distributes the loads. The frame also creates an outside area that links the two buildings together. Being right on the border of the City and Shoreditch, it initiated an ‘overspill’ of office buildings from the City into the surrounding areas, which are slowly being consumed block by block.

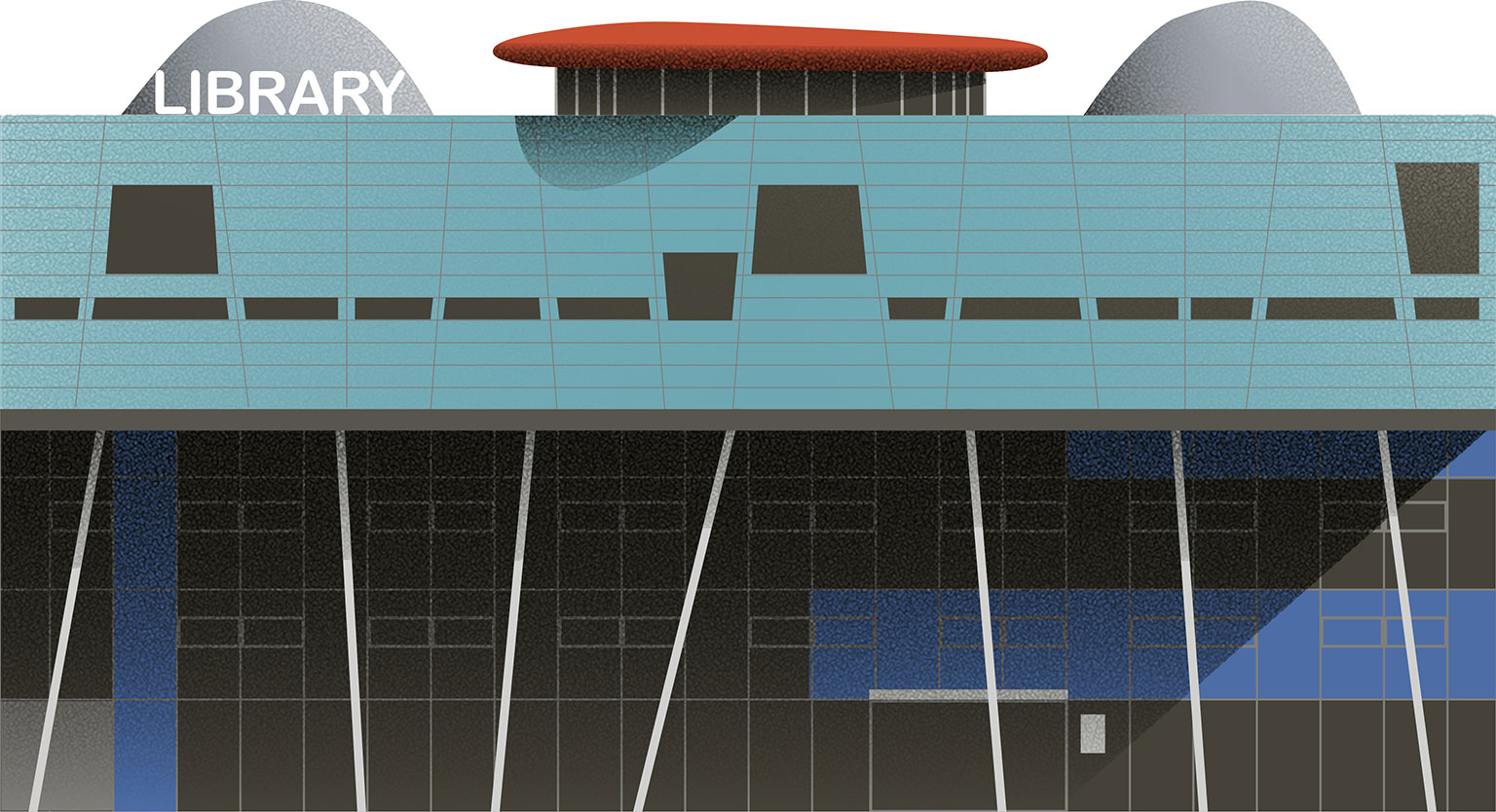

From bartering to books. Peckham Library (108) was part of an ambitious regeneration plan for Peckham, one of the most deprived areas in the city. Northampton-born Will Alsop designed a bold, colourful building that sees the main library space hover above a paved square below, supported by thin columns at varied angles. The decision to elevate the reading rooms (the ground and first floors consist of information and media centres) makes sense once you glimpse the incredible view of London’s skyline. Two ‘pods’ that act as conference rooms break up the main space as well as the roof line, which is also adorned with a bright orange ‘tongue’ that shades a dramatic skylight. For anyone confused as to the building’s purpose, a large sign in friendly rounded letters confirms the site’s literary credentials.

108 Peckham Library

Will Alsop & Christophe Egret

2000

2000  SE15 5JR

SE15 5JR

The design proved to be flexible, too, as parts of the interior had to be rebuilt for changing needs. The original natural ventilation wasn’t enough, as crowds filled the space, and so air conditioning had to be installed. The system didn’t fit in the building itself, and now sits behind it. The new library was a huge success. Its membership skyrocketed and it became especially popular with teenagers – the number of fifteen- to nineteen-year-olds going to the library is twice the average in the borough. Seemingly an impossible brief, calling for a prestigious (but not elitist) building that would attract hard-to-impress young readers, was met. Since then, Southwark Council has built two more brand new libraries in Canada Water, designed by CZWG, and Camberwell.

Sikorsky S-76C++

The official helicopter of the queen and the royal family was upgraded in 2009. It’s unclear whether Prince Harry or Prince William, both pilots themselves, are allowed behind the controls.

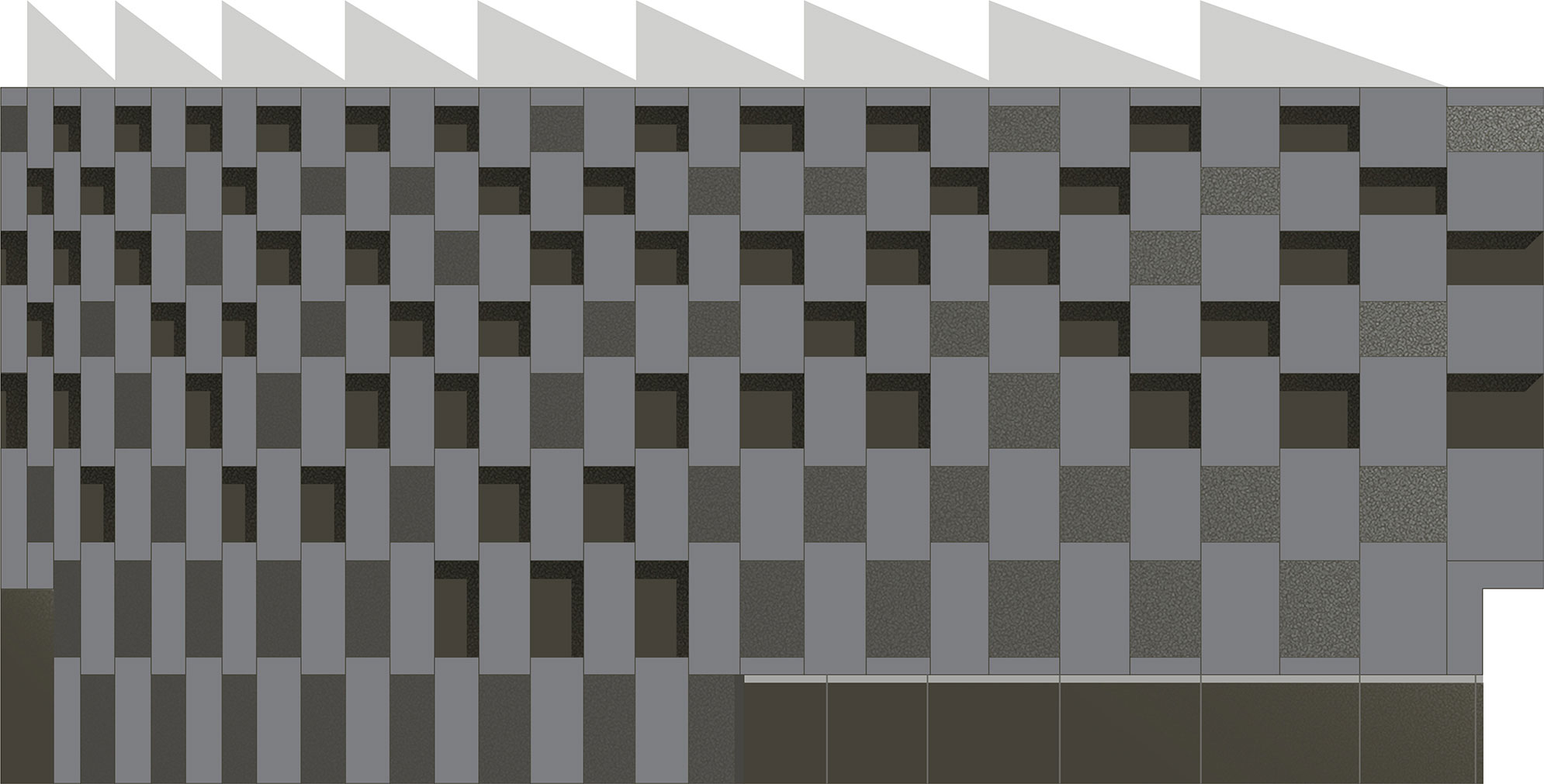

New art galleries were popping up, too. Rivington Place (109) was the first gallery to be backed by public funding for forty years. Shoreditch had recently become popular with the creative industry thanks to a large number of empty warehouses with (initially) low rents. Among these trendy new studios, Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye designed a low-key yet impressive art space. Its dark frontage (Adjaye’s trademark) represents a clever play on perspective. The tight location means that viewers can only really see the building only from one angle, and so Adjaye has made it count.

109 Rivington Place

David Adjaye

2007

2007  EC2A 3BA

EC2A 3BA

The grid of windows and panels grows wider with distance, creating an optical illusion whereby the building appears much shorter than it is. The zig-zag roof structure – a nod to the surrounding factory skylights – uses the same trick, stretching with distance. In addition, there are more rows of windows than actual floors, making the building seem taller. In many cases, the interior rooms have two levels of window – the bottom row offering a street view and the top a nod to the sky.

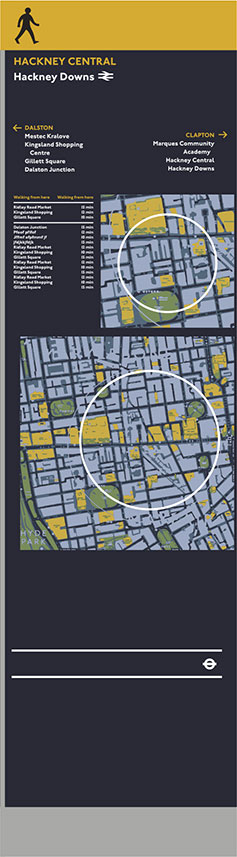

Legible London

A city-wide wayfinding system featuring local maps and travel information was introduced in 2008. Hugely successful, it helps both tourists and locals navigate London’s twisting streets.

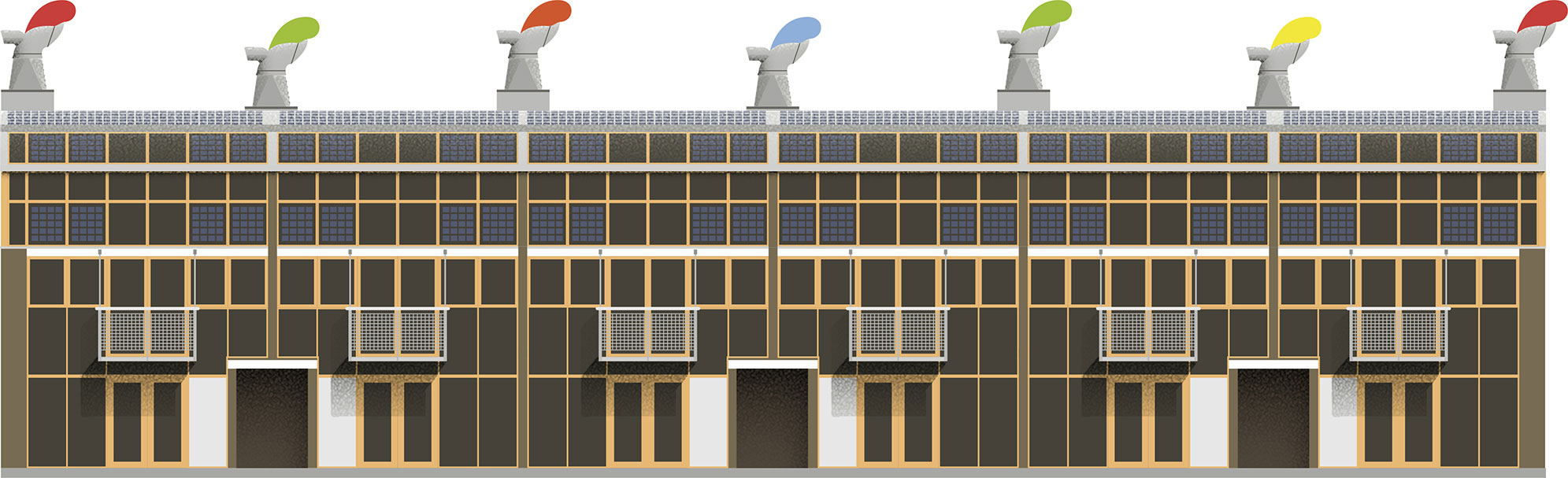

The trend for ‘green’ architecture came to influence not only office architecture, but also new housing. BedZED (110) is an experimental ecological housing development built on the southern outskirts of London, near Croydon. The whole structure was planned with the aim of limiting the carbon footprint of the buildings. Materials, many of them reclaimed, were sourced from as close as possible to the site, in order to limit transport emissions. The flats have glazed conservatories to the south, which capture solar energy, while the coldest north side has only small windows to reduce loss of heat. Other energy solutions include green roofs, thick insulated walls and natural ventilation systems. As a result, the flats use only 40% of the energy required by a typical family home. Proof that it is possible to design sustainable housing without creating something resembling a Hobbit village.

110 BedZED

Bill Dunster

2002

2002  CR4 4HS

CR4 4HS

Much of London’s drive to become more eco-friendly was kickstarted under Ken Livingstone, who became the first London mayor after the position was established alongside the GLA in 2000 (see here). In the 1980s, he had been the leader of the Greater London Council, before it was abolished by Margaret Thatcher’s government. His controversial socialist policies earned him the nickname Red Ken, although as mayor, he was supportive of business and waved through large commercial developments. He greatly improved the London bus network, but his most important legacy is arguably the introduction of the Congestion Charge – an automatic system that charges vehicles driving into central London. Although watered down by Livingstone’s successor Boris Johnson, it still helps to reduce unnecessary car journeys.

Congestion Charge

From 2003, drivers accessing much of central London were required to pay a fee. The system is automatic as traffic cameras scan car registration numbers.