The 1960s mark an era of profound social and political change in the UK, with London at the centre of both movements. Fashion and music are the country’s most successful exports, the economy is prospering and living standards are improving remarkably in the post-war years. But there’s a ticking time bomb buried deep in London’s infrastructure. Modernisation in industry is present but slow, and innovation is in short supply. At the same time, the country is coming to terms with the loss of its empire and its changing position in world politics; former enemies Japan and Germany are experiencing miracle recoveries and are now unexpected economic competitors. For now, optimism reigns, but a shock is in store.

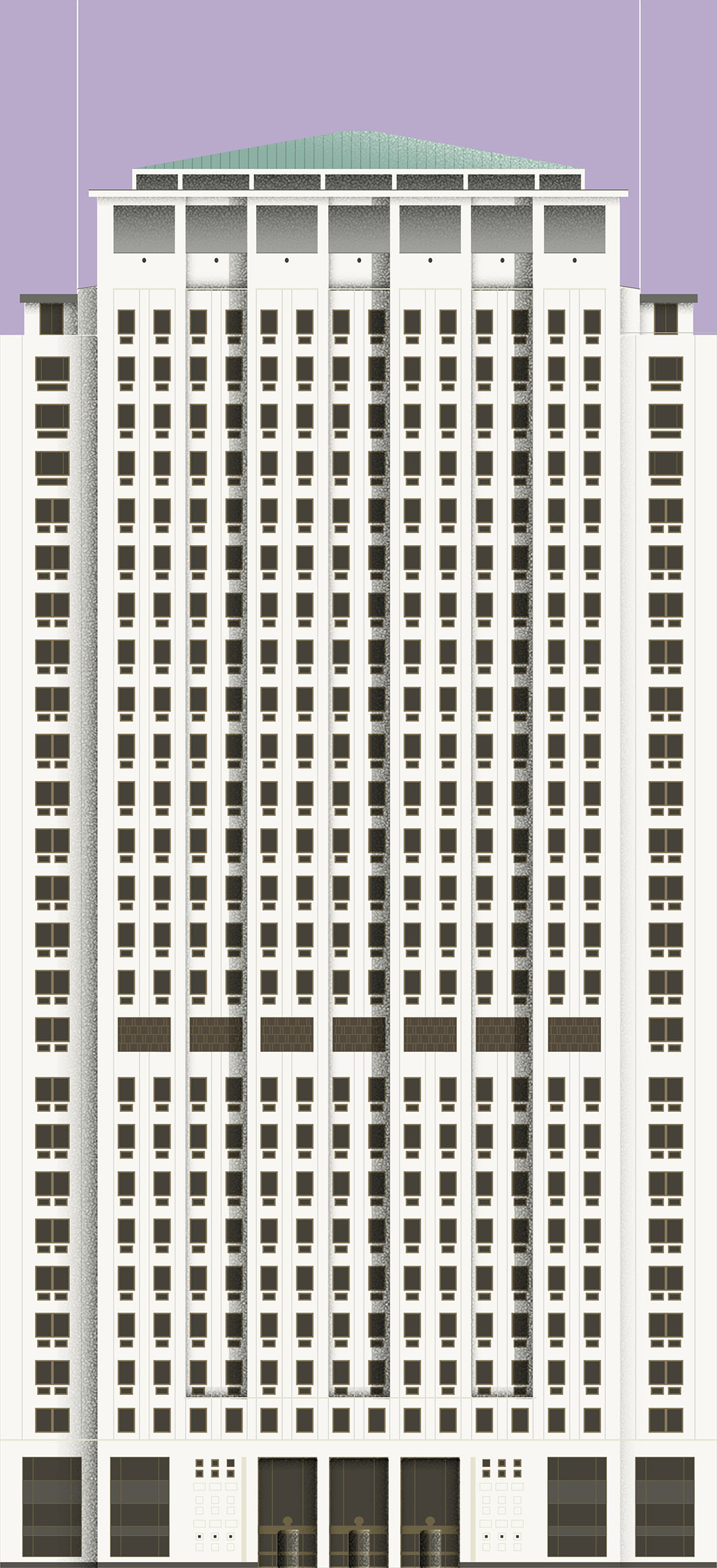

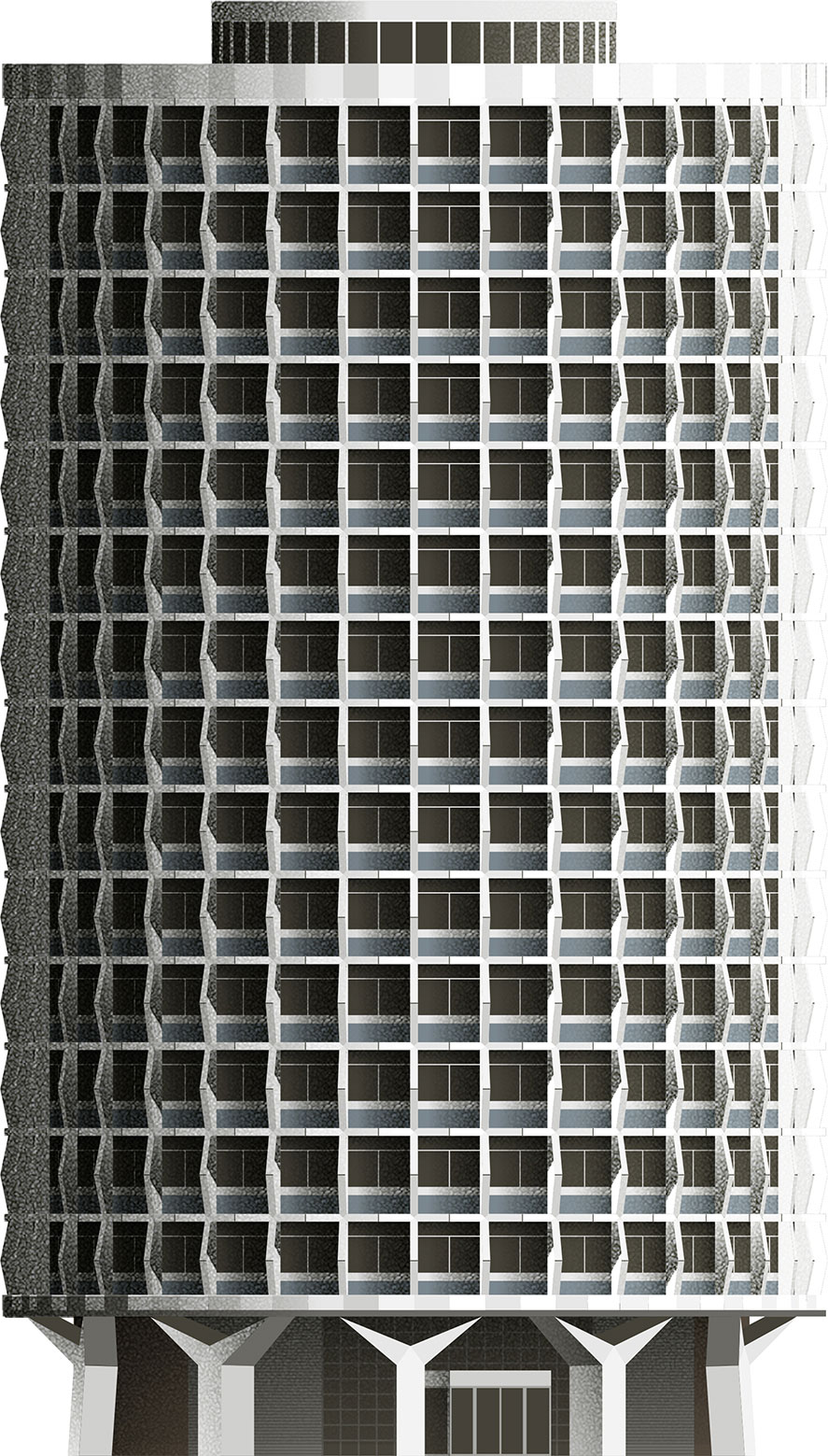

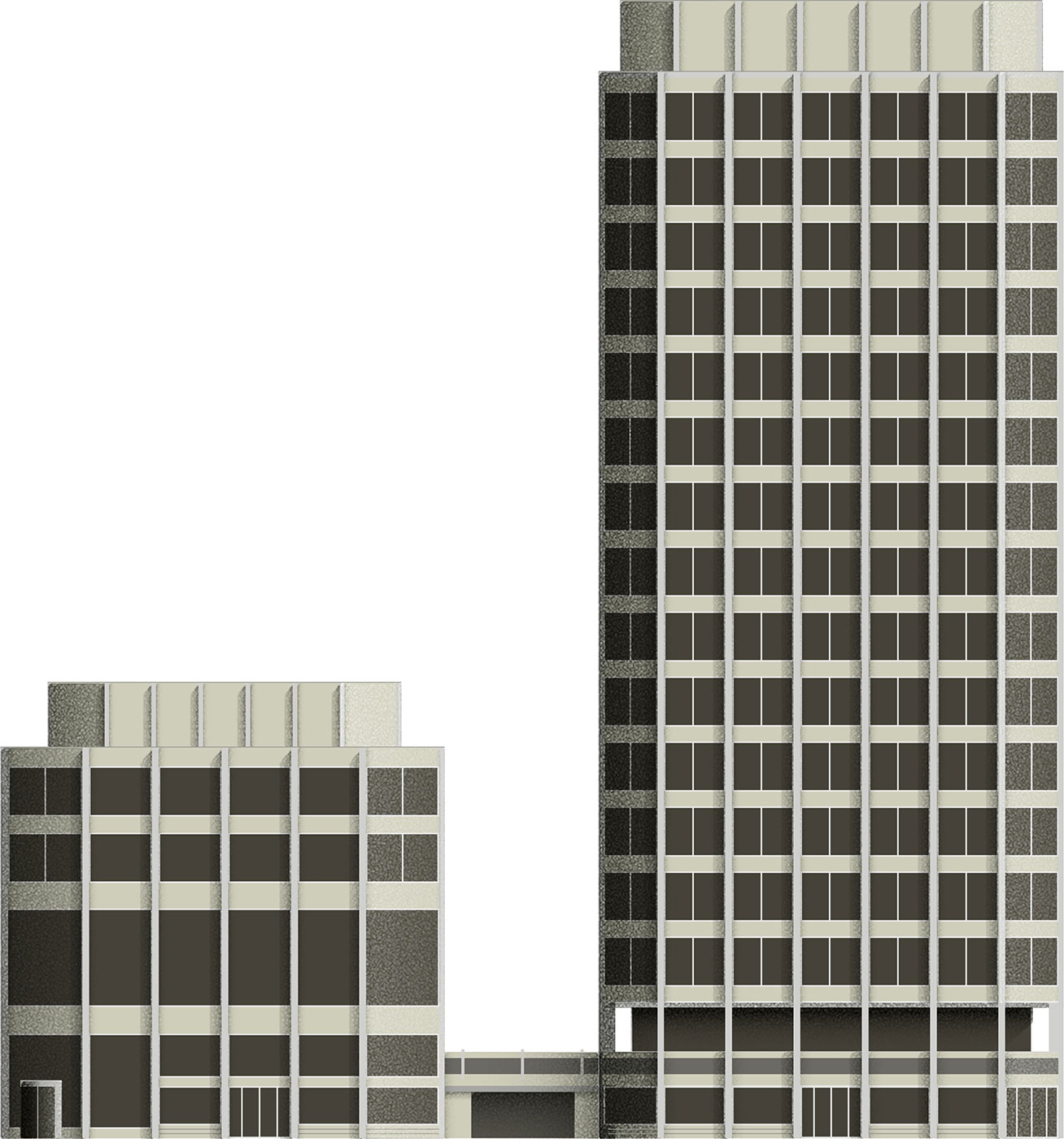

As the pavilions of the 1951 Festival of Britain were demolished, part of the South Bank site was taken over by the Royal Dutch Shell Group, a massive British-Dutch oil corporation. The Shell Centre (049), its new UK headquaters, opened ten years after the festival closed its gates. While the festival architecture had been progressive and futuristic, the Shell Centre looked to the past. Dull, monotone façades were clad in Portland stone and the windows were framed in bronze. Surprisingly so, since the architect – Salt Lake City-born Howard Robertson – had helped design the strikingly modernist UN headquarters in New York City.

049 Shell Centre

Howard Robertson

1961

1961  SE1 7NA

SE1 7NA  107M

107M

Two large nine-storey blocks accompanied a 107-metre-tall tower, which was the tallest office building in London at the time. The complex as a whole became the largest office building in Europe, by floor space. Staff enjoyed lavish facilities such as squash courts, a swimming pool, badminton courts, a cinema, restaurants, a theatre, exhibition spaces and even a rifle range. The complex is now being redeveloped and the tower, the only surviving part of the original development, now heads a whole cluster of high-rises.

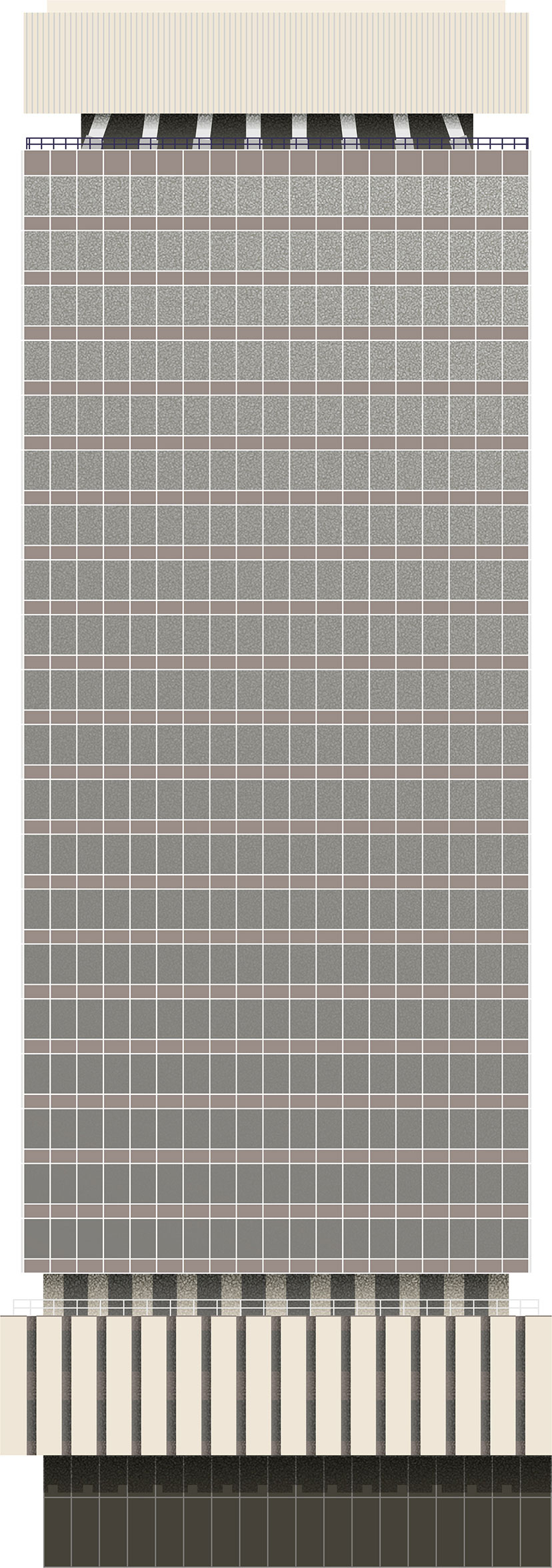

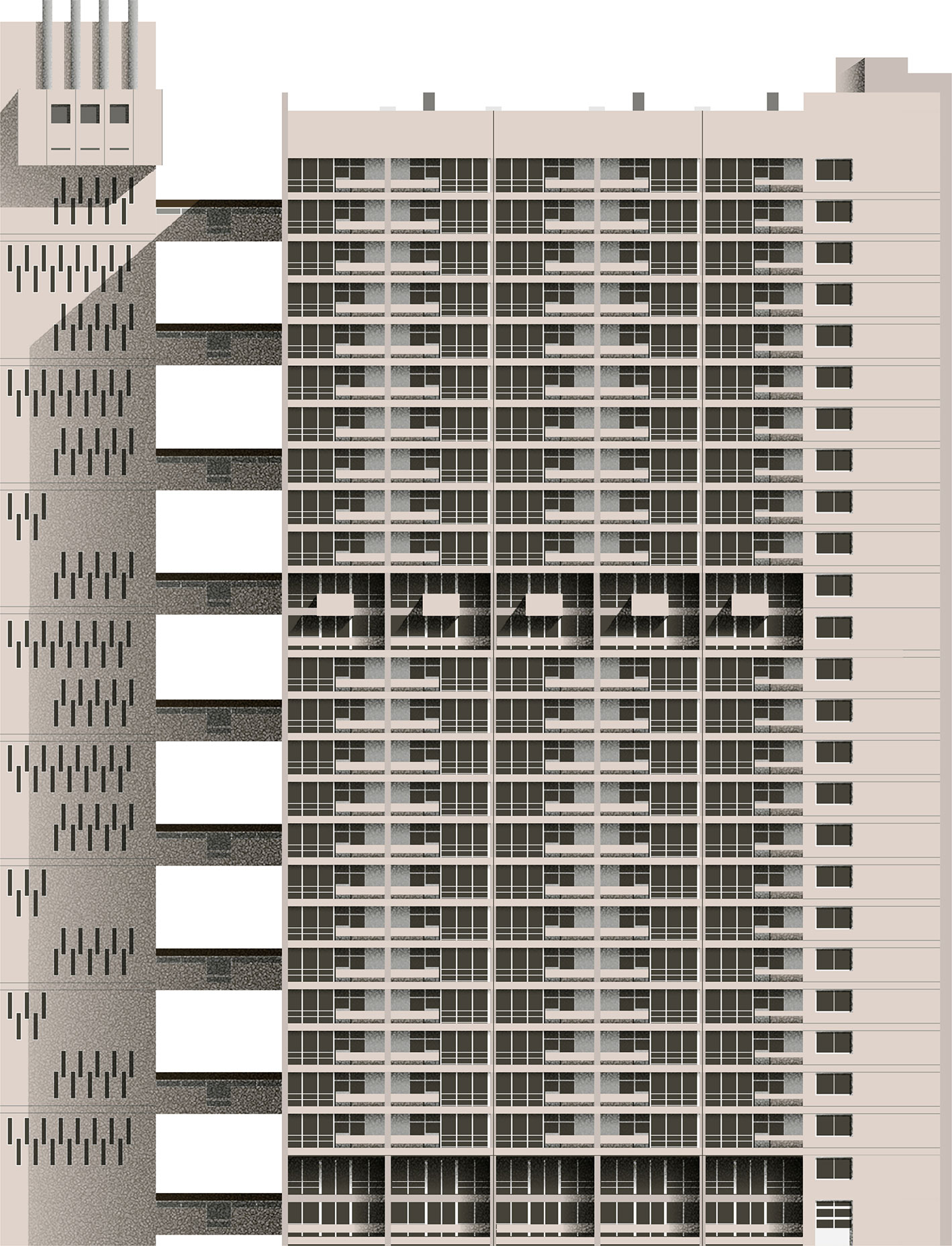

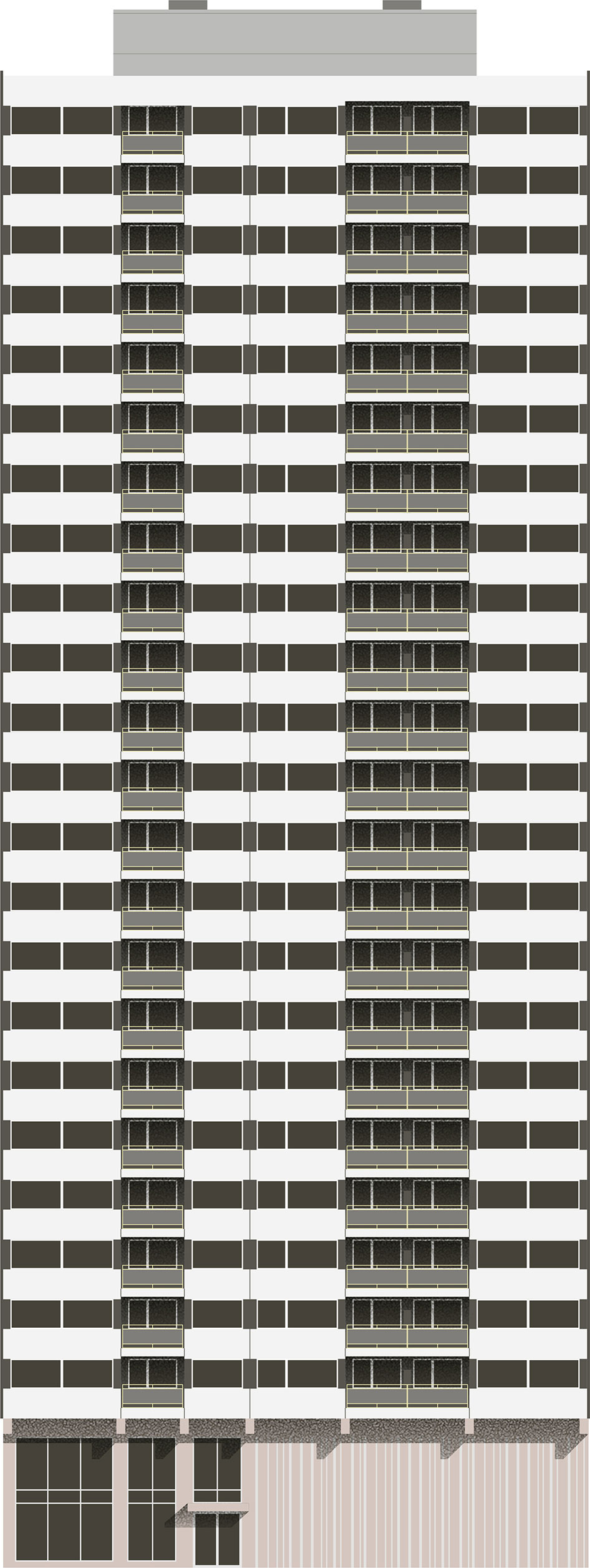

If the Shell Centre was old fashioned, Vickers Tower (050) (now renamed Millbank Tower) was cutting edge. Designed by Ronald Ward and Partners, it opened just two years later, and was pioneering in its glass curtain façade – a lightweight structure that acts as the building’s ‘skin’. It beat the Shell Centre in height by eleven metres, and the curved tower resembles a butterfly in plan. As its name suggests, it was originally built for Vickers, a famous engineering company that produced military and civil aeroplanes, tanks and trucks. This was a high point for the company – it would later be subsumed by various mergers, a result of the gradual nationalisation of the whole industry that occurred over subsequent decades.

050 Vickers Tower

Ronald Ward and Partners

1963

1963  SW1P 4QP

SW1P 4QP  118M

118M

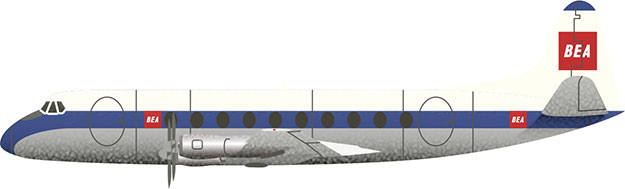

Vickers Viscount

The first turboprop airliner in the world became the most successful product of post-war British civil aviation.

The renewal of the City that had begun in the previous decade continued in earnest during this period. Tottenham-born architect William H. Rogers was one of the key figures in the regeneration project, and his innovative office buildings replaced many of the burned-out shells left after the war – in many cases merging different sites together to allow for even greater buildings. Rogers travelled to New York and Chicago, where he admired towering skyscrapers clad in curtain wall façades. Back in London, he had to battle with conservative City planners for every floor.

His 20 Fenchurch Street (051) was the ‘first generation’ skyscraper in the City. A central core was topped with a huge three-storey-high roof structure. This massive ‘umbrella’ carried the curtain façade that covered the entire building. The feat of engineering ensured the interior was free of clutter – something unseen at the time, when thick structural walls or series of columns fractured standard office spaces. The windows of the sleek, lightweight façade were covered in a reflective film in order to protect the space from overheating in the sun.

051 20 Fenchurch Street

William H. Rogers

1968

1968  EC3M 8AF

EC3M 8AF  91M

91M

Although the building was pragmatic in design, the continuous improvement of construction technology and rising office standards made it obsolete. In the never-ending cycle of the redevelopment of central London, the building had to make way for a new generation. Its unusual top-hung structure was a headache for demolition experts in 2008. Six years later, it was replaced by the Walkie Talkie (116) – a skyscraper almost twice as high as the previous building.

While most of London’s commercial architecture experiences a relatively short life span, traditional institutions have always been keen to build landmarks designed to stand the test of time. The Royal College of Physicians (052) wanted to rebrand itself as modern and accessible. Its new building was an ideal opportunity to do just that. Denys Lasdun was selected as the architect because of his uncompromisingly modern and confident work. But the architect wasn’t thinking only about looks; he was focused on the function and the people inside.

052 The Royal College of Physicians

Denys Lasdun

1964

1964  NW1 4LE

NW1 4LE

Lasdun spent weeks observing aspects of RCP life in the old building. Its new home next to Regent’s Park was designed with this research in mind. The three-storey building sees each floor grow larger, resulting in an inverted ziggurat shape – not an uncommon feature in modernist design. Narrow vertical windows, designed to avoid the potential distraction of a good view, are seemingly randomly scattered around. The building is now listed, and highly rated to this day – something that sets it apart from its contemporaries.

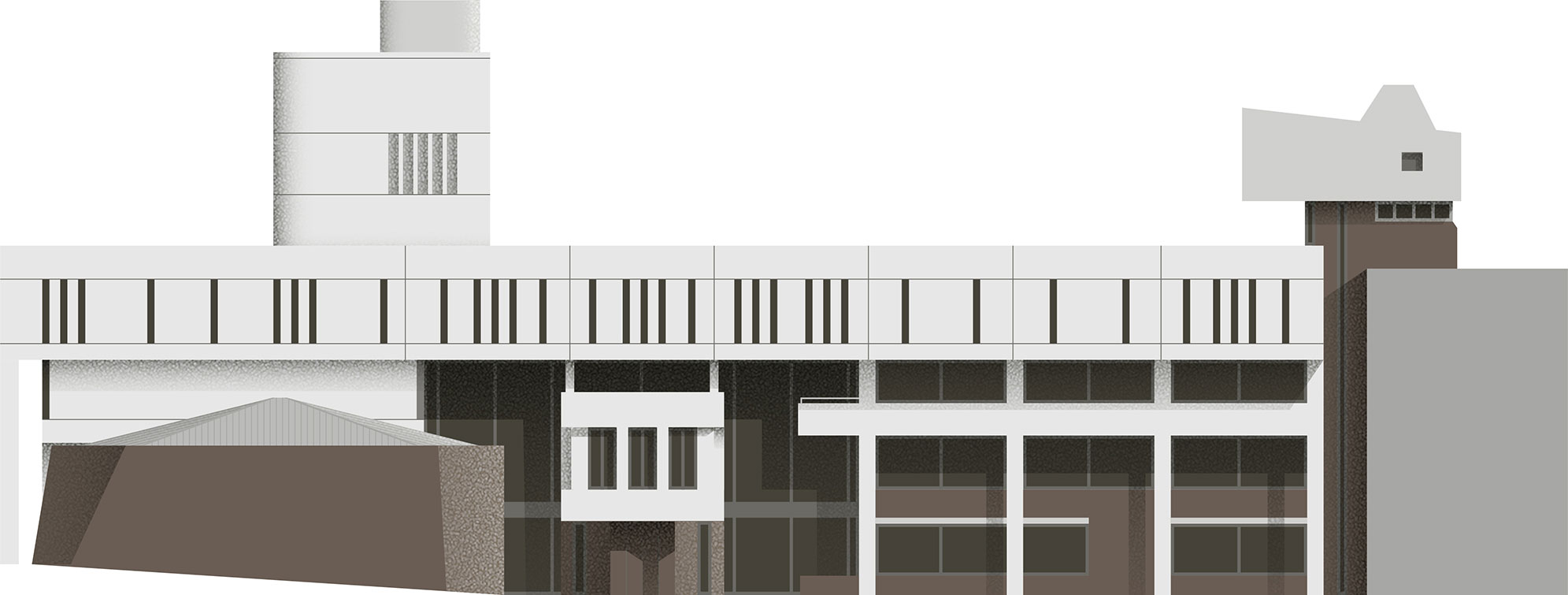

Very few industrial buildings are lucky enough to be preserved, let alone celebrated. Bankside Power Station (053), now home to Tate Modern (103), is a rare exception. But the building wasn’t always liked – quite the opposite. It caused controversy from the first proposal. Planned on the South Bank in 1944, its development was in conflict with the desired restructuring of the area for offices, educational and cultural institutions. But the extremely cold winter of 1947, which saw London grind to a standstill amid sweeping power cuts, revealed a growing demand for electricity. The government approved the building against significant opposition from the borough council and local residents.

053 Bankside Power Station

Giles Gilbert Scott

1963

1963  SE1 9TG

SE1 9TG  99M

99M

Architect Giles Gilbert Scott was brought onto the project to address reasonable concerns about the dwarfing of St Paul’s Cathedral. He adapted the original plan so in place of two tall chimneys stood one central chimney, which was lowered so as not to exceed the height of St Paul’s. This assisted visually, but the relatively short chimney caused pollution problems. In addition, due to temporary shortages of coal (the mining industry was still recovering from the Second World War), the station was redesigned to burn oil instead of coal, which would prove a terrible mistake in the oil crisis of 1973. The station was completed in two stages – the first half opening in 1952 and the second in 1963. It closed only twenty years later.

Bus Lane

First introduced as an experiment on Vauxhall Bridge in 1968, the designated bus lane was an attempt to free London buses from congestion. Today, bus lanes cover much of central London and are shared with taxis and cyclists.

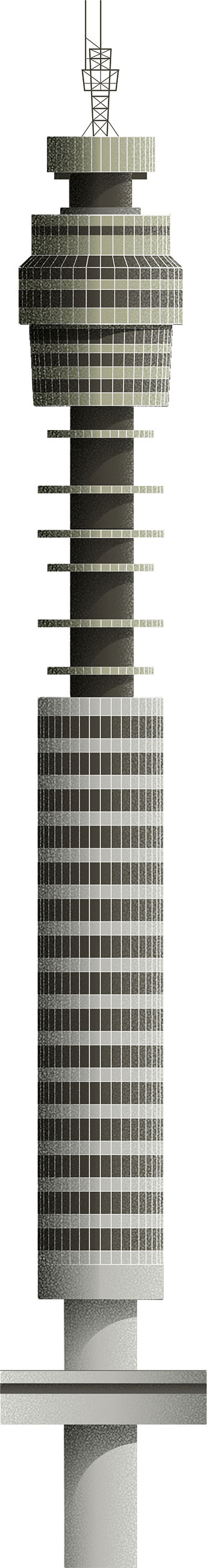

More exciting additions to the skyline were rising towards the clouds. In quiet Fitzrovia, a technological revolution was under way. The latest exciting addition was the Post Office Tower (054) (now the BT Tower). It was built high enough to get a direct line of communication over the Chiltern Hills and up to the next tower in Birmingham. As an important element in the UK’s new microwave telecommunications network, built at the height of the Cold War, it was also designed to withstand a nuclear explosion from only a mile away. The cylindrical design was chosen as the most suitable to sustain an atomic blast, as well as strong winds. After construction began, the decision was made to add a viewing platform and rotating restaurant (inspired by a trend from North America and Central Europe). When completed, it became the tallest building in London, beating Battersea Power Station, which at that point was still under construction.

054 Post Office Tower

Eric Bedford and G. R. Yeats

1965

1965  W1T 4JZ

W1T 4JZ  190M

190M

The tower, designated as an official secret due to its strategic importance, could not appear on maps for a long time. This was bizarre, not only because everyone could see the tower from almost everywhere in London, but also because hundreds of thousands of people visited the top. In 1971, a suspected IRA bomb was planted, blasting a large hole in the tower. The viewing platform has been closed ever since, and the restaurant followed suit in 1980. Today, the viewing galleries and former revolving restaurant are still, surprisingly, intact – and are sometimes used for special events and launches.

Austin Mini

These micro-sized cars squeezed into London’s traffic jams and became one of the symbols of swinging sixties Britain. Every member of The Beatles had one, as well as 5.4 million other people around the world.

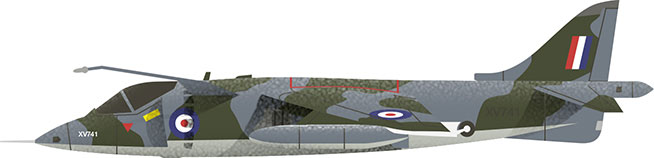

Hawker Siddeley Harrier

In 1969, the Transatlantic Air Race – between the top of the Post Office Tower in London and the Empire State Building in New York City – was staged. A pilot was hurried on a motorcycle from the tower to St Pancras Station, where a Harrier jump jet was already waiting. After a vertical take-off, he flew across the pond (with some mid-air refuelling). Some six hours later, the airplane landed in Manhattan. The air race was won by the other pilot (in a supersonic Phantom), but it was still a great PR stunt for the new jet.

It was not only the government sector, but also the private sector that had pound signs in its eyes during this period. The government relaxed planning laws in a bid to stimulate economic growth and replace jobs in manufacturing. This caused a steep rise of speculative office development in London, on a scale never seen before. Swiss-born Richard Seifert became one of the most economically successful British architects of the century, thanks to his detailed knowledge of planning law and ability to exploit its loopholes and maximise the profits of his clients. His practice R. Seifert and Partners produced designs incredibly fast and completed some 600 buildings around London during his lifetime. The most (in)famous and controversial of Seifert’s buildings is Centre Point (055).

055 Centre Point

R. Seifert and Partners

1966

1966  WC1A 1DD

WC1A 1DD  117M

117M

The project began when London County Council attempted to buy the land surrounding one of the busiest junctions in central London, where they hoped to build a gyratory system. The landowners were dissatisfied with the money the council was offering and the whole deal stalled. However, the wily property tycoon Harry Hyams took advantage of the delay and bought out all the land right under the council’s nose. He then offered the council the space needed for the gyratory in exchange for an allowance for extra high development.

Designed by Seifert’s partner George Marsh, Centre Point was constructed between 1963 and 1966. The slender tower has a façade of precast panels, which were hung from the frame without the use of scaffolding – it was the first tall building in London to be constructed this way. The T-shaped panels create a beautiful pop-art pattern, reminiscent of honeycomb. But the street level, typically for Seifert’s studio designs, is badly planned and unfriendly to pedestrians.

When the building was finished, the office property market was already saturated. The developer decided to wait for prices to rise and left it empty, including all the flats, for thirteen years during a housing crisis. Its prime location and scale made it the perfect symbol of a property developer’s greed. The building was invaded by protestors and squatters a number of times. True to form, it has now been redeveloped into luxury apartments.

Space House (056) was built just a couple of streets away from Centre Point in Holborn. It shares not only the same architect and developer, but also a similar building system. A visually striking and confident façade comprises Y-shaped precast panels, assembled in a circular plan sixteen storeys high. As with other buildings of the practice, the ground level is underwhelming.

056 Space House

R. Seifert and Partners

1968

1968  WC2B 4AN

WC2B 4AN

But pedestrians were not at the top of the priority list. Car ownership rose dramatically in the 1960s. London’s streets were already full of buses, cabs and vans; increasingly affordable cars flooded them. Optimistic town planners, taking cues from Colin Buchanan’s influential book Traffic in Towns, believed that allocating more space for the traffic would solve congestion, while pedestrians would be safely separated by a system of elevated walkways.

AEC RML Country Bus

The successful Routemaster bus was extended by a row of extra seats, hence the square window in the middle. It is seen here in the green livery of the London Country buses that served the suburbs.

In the 1960s London Bridge was deemed too narrow and it was sold to an American oil tycoon, who rebuilt it in the Arizona desert. Big chunks of the city were demolished to make way for wider roads and roundabouts. Only a lack of money and rising opposition prevented the altogether insane plans from fully materialising. People discovered that wider roads only invited more traffic. Traffic casualties hit an all-time high, and it didn’t take long for average speeds to get back to the era of the horse and cart.

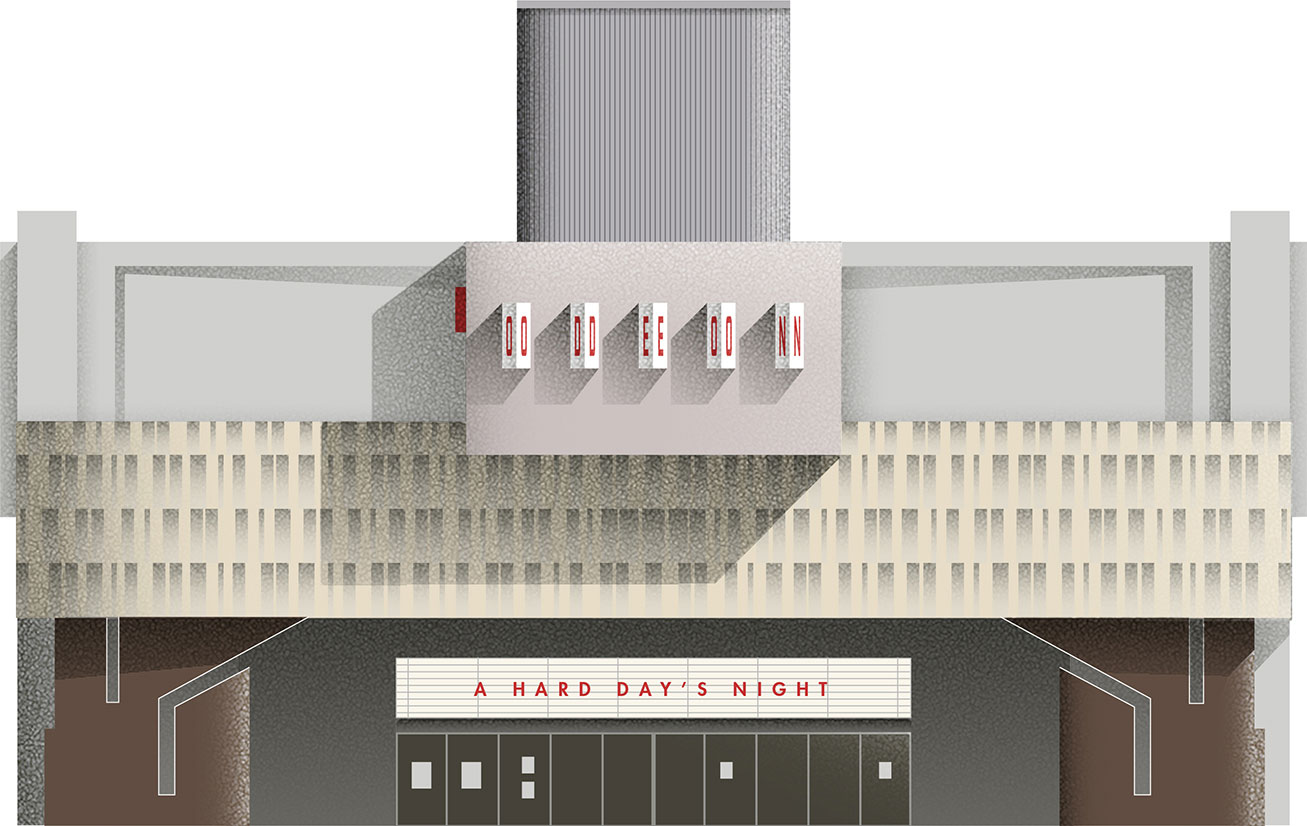

The rebuilding of Elephant & Castle was the embodiment of this optimistic traffic planning. Envisaged as the ‘Piccadilly Circus of the South’, it received a radical makeover. Old streets and buildings were erased. The new Elephant & Castle Odeon (057) replaced the 1930s Trocadero 3,000-seat cinema.

057 Elephant & Castle Odeon

Ernő Goldfinger

1988

1988  1957

1957  SE1 6TE

SE1 6TE

It was designed by Ernő Goldfinger, who was responsible for the new office buildings around it, too. It was the only brutalist cinema in London. The cinema had just a third of the seats of the Trocadero cinema it replaced, but this was more than enough in the 1960s, when televisions had invaded the living rooms of most Londoners. The cinema was demolished only twenty-two years later.

Goldfinger was now in demand, after decades of little or no work. However, his name had already become famous, albeit for reasons other than his work. Known for his bad temper, he didn’t sit well with his Hampstead neighbour, the writer Ian Fleming, who also disliked Goldfinger’s new, modern house. The villain in Fleming’s James Bond novel of 1959 was clearly inspired by the architect – not only sharing his name, but also his Eastern European background and Marxist beliefs.

The architect was enraged, but busy with new commissions. Work on new housing in east London finally gave him the chance to put his housing theories in practice. Balfron Tower (058) in Poplar is a massive, twenty- six-storey concrete block. The floors are accessible through a separate lift tower, connected by bridges on every third level. Goldfinger had control of both the design and the residency allocation – he had records of all residents, listing their ‘suitability’ to live in the high-rise building.

058 Balfron Tower

Ernő Goldfinger

1967

1967  E14 0QR

E14 0QR  84M

84M

Rehousing them by the streets they originally lived in, he tried to keep communities together. On completion of the block, he moved with his wife into a top floor flat for two months. The Goldfingers organised cocktail parties for the tenants as a means of collecting their comments and suggestions. He used this knowledge to design the famous Trellick Tower.

Elephant & Castle Statue

The area takes its name from the sign of a local pub. A statue from the demolished pub was preserved and moved into a new shopping mall in 1965.

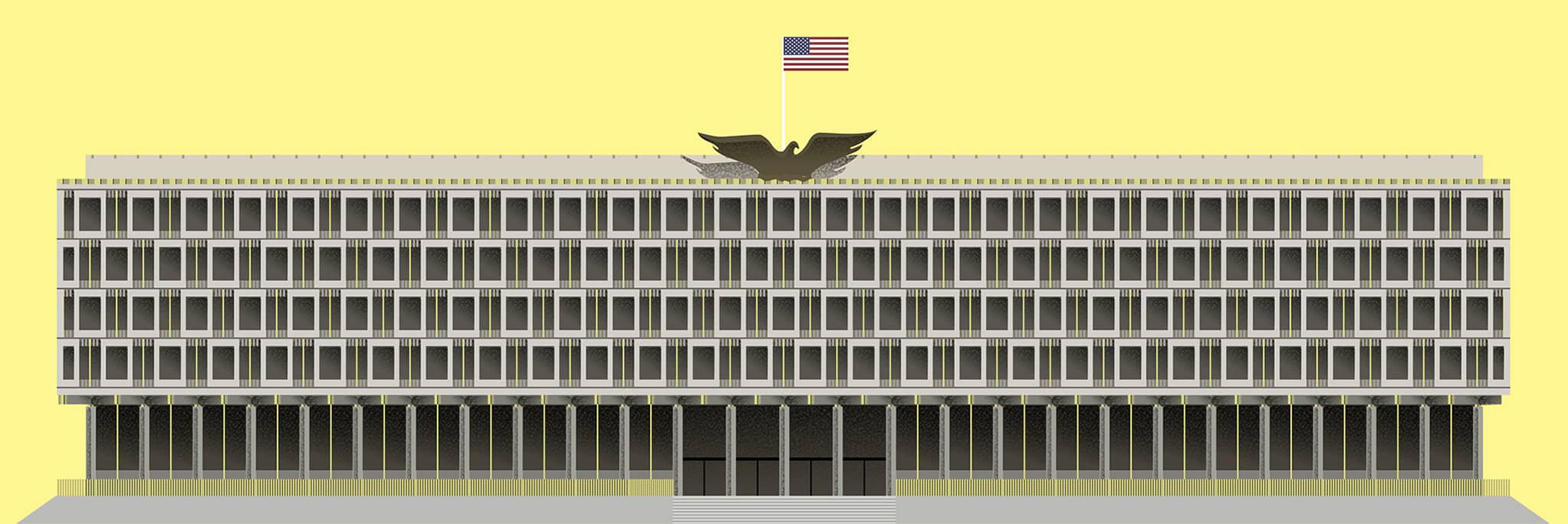

This was a revolution in terms of access to housing for the masses – and elsewhere too new doctrines were forming and established orders were being challenged. World politics was heating up and protests against the bloody Vietnam War spread across the world. The new US Embassy (059) in Grosvenor Square, Mayfair, opened just in time to receive its fair share of demonstrations. It became London’s first purpose-built embassy (until then the habit was to repurpose existing buildings) and was designed by Finnish-American architect and designer Eero Saarinen. The powerful modern building was inspired by Greek temples and is strictly symmetrical, proudly sitting on a podium.

059 US Embassy

Eero Saarinen

1960

1960  W1A 2LQ

W1A 2LQ

The embassy’s scale and modernity, unseen in Mayfair, proved to be controversial. It has only six storeys (plus three underground), but the width takes over a whole block. The central entrance is accented by a bronze eagle with a ten-metre wing span, balancing on a roof edge above. The embassy attracted several mass demonstrations against the Vietnam War and US foreign politics and had to be protected from the crowds by police cordons. The embassy is now at the end of its life, as the US has moved its mission to a new fortress-like building near the revived Battersea Power Station complex. The old Mayfair embassy is slated to become a luxury hotel.

Jaguar 340 3.8

The Metropolitan Police Service operated a fleet of Coventry-built Jaguars. Most of the police cars at the time were unmarked and only recognisable by the blue beacon on the roof. The high-visibility paint schemes came later.

Not far from Grosvenor Square is St James Street. The Economist Buildings (060) there were designed by husband and wife team Alison and Peter Smithson. An eccentric couple, they dressed in quirky clothes and drove around in an old army Jeep. The Smithsons built relatively few, but important, buildings, which gained them international fame and an almost cult following in Britain. The development for The Economist magazine is arguably their best work.

060 The Economist Buildings

Alison and Peter Smithson

1964

1964  SW1A 1HG

SW1A 1HG

Because the size of the original plot was quite small, the client bought out its neighbours or promised them space in the new development. Instead of replacing the bundle of old buildings with one large tower, the architects designed three smaller blocks that sit around a modest plaza. All this stands on a podium that conceals a car park.

The tallest tower was reserved for the magazine, with the top floor forming a penthouse for the chairperson. The other two towers were reserved for the original occupants of the site – a gentleman’s club and a bank. The architecture is unimposing and has aged better than most of its contemporaries. In 1988, it became the first 1960s building in Britain to be listed.

Kiosk No 8

The new telephone box was introduced in 1968. Architect Bruce Martin simplified the classic No 6 to the bone, so that it was easier to maintain and harder to vandalise.

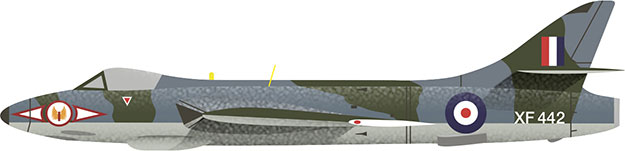

Hawker Hunter

Pilot Alan Pollock decided to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the RAF in his own way. Angry that the government didn’t want to celebrate, he flew his jet around the Houses of Parliament at low level and then, in an incredible stunt, flew through the middle of Tower Bridge.

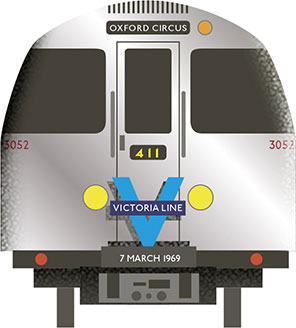

Victoria Line

The first stage of the new line opened in 1968. It was full of new cutting-edge technology, including automated trains and ticket gates. It was also the first new central Underground line to be built in over sixty years.

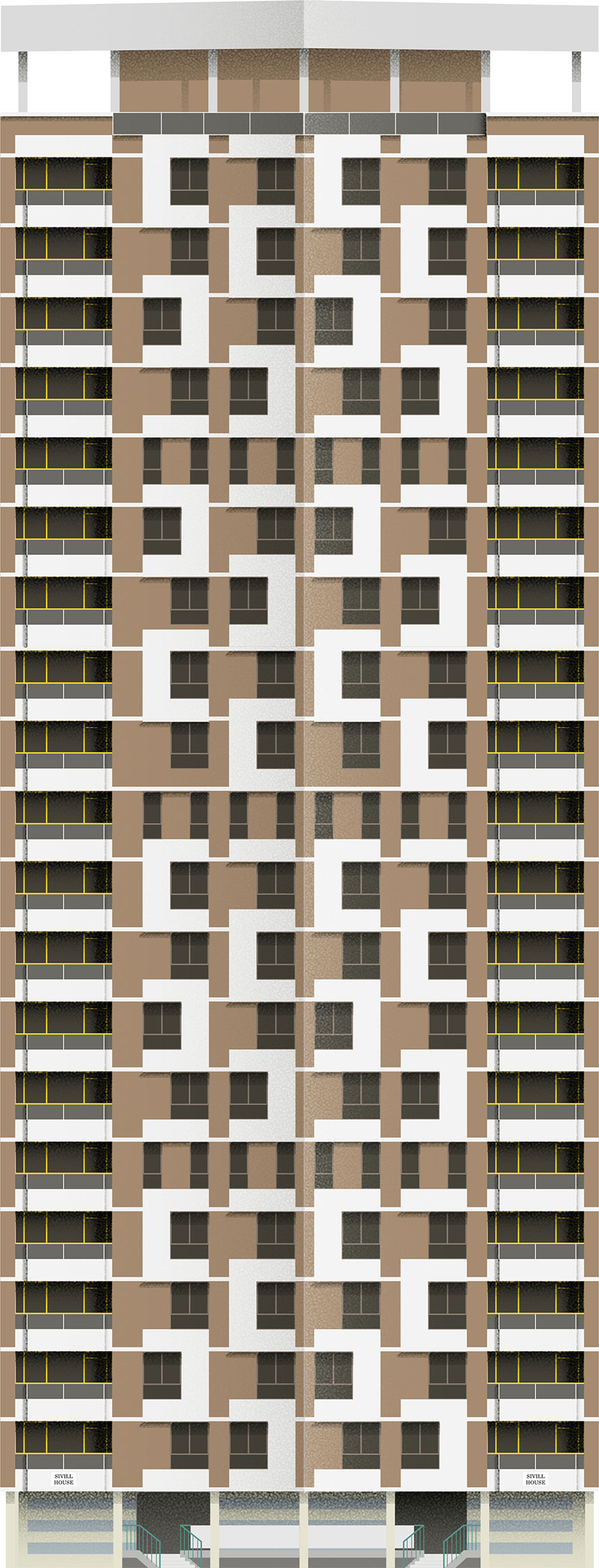

During the 1960s, housing remained a priority. Handsome Sivill House (061) in Shoreditch was designed by Berthold Lubetkin and his former colleagues from Tecton. Similar to their previous Spa Green Estate (035) and Hallfield Estate (041), the façade resembles a piece of abstract art and is supposedly inspired by a Caucasian carpet. C-shaped concrete panels decorate the front in a changing rhythm. Although this didn’t impress the younger generation of architects, who had already grown weary of the architect’s obsession with patterns, believing them a thing of the past. Inside is an extravagant curved central staircase, which one would more readily expect in an upscale mansion than in a council housing project. However, Lubetkin, a life-long communist, believed ‘nothing is too good for ordinary people’.

061 Sivill House

Berthold Lubetkin, Douglas Bailey, Francis Skinner

1962

1962  E2 7PH

E2 7PH  59M

59M

In contrast, many councils built their housing from prefabricated systems with little adaptability. This helped to reduce time on a construction site, since most of the work was undertaken in a factory. The government pushed for the replacement of old housing with new estates, rather than the refurbishment of existing structures.

Councils were given subsidies when building high – but there was a problem on the horizon. A gas explosion in a kitchen of a flat in Newham caused the complete collapse of a whole corner of Ronan Point (062) tower, which killed four tenants and injured seventeen. Following an investigation, it was revealed that the explosion was relatively minor (the lady preparing her tea survived) and the building was supposed to withstand it. But closer inspection revealed shockingly low standards of construction.

062 Ronan Point

Newham Council Architects’ Department

1968

1968  E16 3EQ

E16 3EQ

Due to a nationwide shortage of builders, the estates were constructed by an army of mostly unskilled ‘assemblers’. In Ronan Point, shoddy work led to defects that left gaps between construction panels — these were then simply covered up by floor boards and wallpaper. The unsound building was, in a bizarre sequence of events, strengthened after the explosion, and the tenants moved back in. But the press latched on to the tragedy and high buildings lost most of their remaining appeal. System building techniques were also revealed to be a big problem, with poor workmanship proving the ultimate source of the tragedy.