London’s streets, clouded in record-breaking toxic pollution, are changing dramatically once more. New cycle paths criss-cross the city, a number of electric buses are on the roads and black cabs are slowly following suit. New buildings are now more efficient and low-energy consumption has become a (sometimes overblown) sales point. But it’s not all rosy. Councils and building companies are failing to provide enough homes for a growing population. And yet London’s skyline is changing faster than ever amid skyscraper madness – towers are appearing everywhere, even in boroughs previously untouched by high-rises.

Preparations for the 2012 Olympic Games in London were hugely affected by the unfolding financial crisis. The previous summer Olympic Games in Beijing had been the most expensive so far, as China wanted to prove itself as a global power. Britain’s winning bid in 2005 for the 2012 games was rather more modest, but even that budget was to prove too grand when the crisis hit. A revamped plan was set in motion to deliver a sustainable and affordable games. Post-industrial zones of the Lee Valley in east London were transformed into an impressive Olympic Park, designed to require minimal maintenance. 98% of building waste from the demolished factories on the site was reused or recycled.

With a ‘legacy’ in mind, stadiums for less popular sports were only temporary structures, since they wouldn’t attract enough users after the Games.

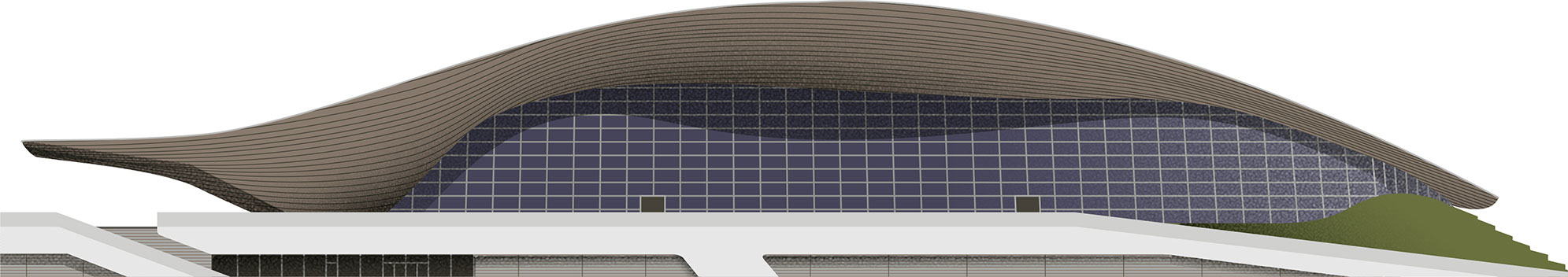

Thankfully, a reduced budget didn’t stand in the way of good architecture. Zaha Hadid’s design for the Aquatics Centre (111) was chosen via an international competition, long before the decision to make the Games more sustainable and economically viable – the original design had to be scaled down and compromised to reduce the cost, although the building still cost three-and-half times the intended budget. The main feature of the stadium is an elegant, wave-inspired roof, typical of Hadid’s work.

111 Aquatics Centre

Zaha Hadid Architects

2011

2011  E20 2ZQ

E20 2ZQ

But what seems so natural and light is held together only thanks to an extremely complex roof structure that is twelve metres thick at some points. The engineers from Arup probably had nightmares about it long after they finished the work.

The venue had to be built with a large enough seating capacity to accommodate the Olympic crowds, but also to account for the fact that they would struggle to fill seats once the Games were over. A clever solution came in the form of two temporary wings, with a total of 15,000 seats, that were built alongside the stadium. The wings were later removed and the sides closed off with a glazed façade; the capacity is now just 2,500 seats.

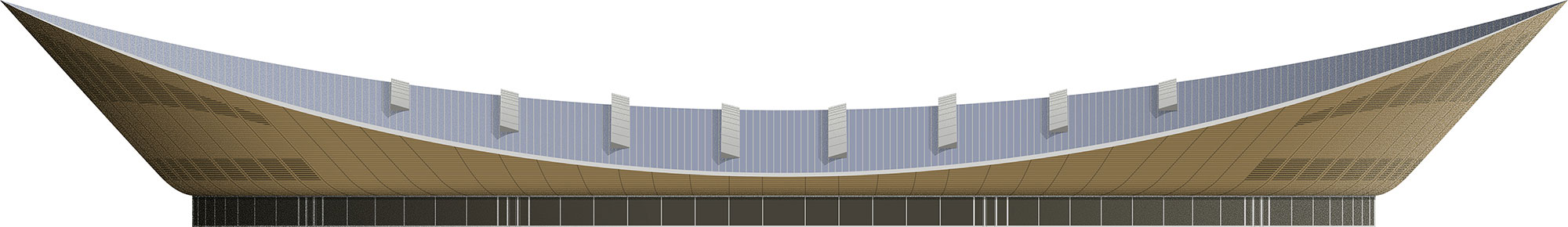

The Velodrome (112), built at the other end of the Olympic Park, is a work by Hopkins Architects. They had the perfect advisor in British track cyclist Chris Hoy, who won three gold medals in Beijing (and a further two in the Velodrome). The simplest way to describe the stadium’s shape is to use its nickname, The Pringle (a favourite crisp snack in the UK). Unlike the Aquatic Centre, the building’s form is a result of a pragmatic merging of engineering and design. The roof, ten times lighter than Hadid’s, is made from a net of thirty-six-millimetre-thick cables. The cables are set in a grid pattern and covered with timber and waterproof membrane. The efficient building exceeded requirements for sustainability and was delivered ahead of schedule and on budget.

112 The Velodrome

Hopkins Architects

2011

2011  E20 3AB

E20 3AB

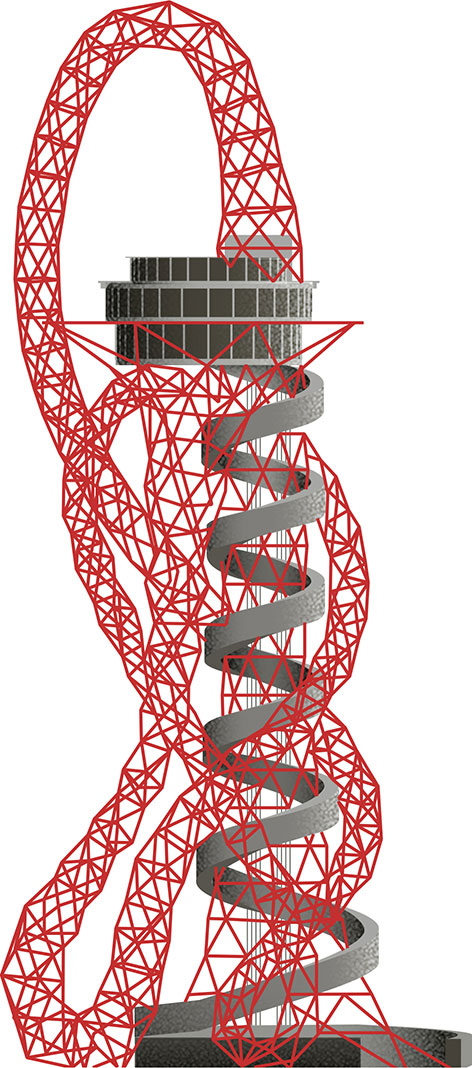

The beautifully landscaped Olympic Park, which can retain water in the case of floods, is spoiled by the glowingly red ArcelorMittal Orbit Tower (113). The strange structure wasn’t in the masterplan at all, but was pushed through by the then mayor, Boris Johnson. It didn’t matter that it contradicted the London Games’ ethos of austerity and sustainability – Johnson claimed that the Olympic area needed ‘something extra’, and chose a design for a huge sculpture (complete with a spiral walkway and public viewing platform) by artist Anish Kapoor and engineer Cecil Balmond. Perhaps the only positive thing about this tower-sculpture is that it was largely paid for by Indian steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal and not by British taxpayers.

113 ArcelorMittal Orbit Tower

Anish Kapoor & Cecil Balmond

2014

2014  E20 2AD

E20 2AD  114M

114M

Boris Johnson was London mayor between 2008 and 2016. Originally a political journalist, he was very keen to leave his mark on the capital. A cyclist himself, he helped to improve cycling safety and supported the building of numerous new cycle paths. That said, the system of hire bicycles is unfairly nicknamed ‘Boris Bikes’, as it is technically Livingstone’s work. Unfortunately, many of Johnson’s other projects were megalomaniac and ended with mixed results. The unnecessary ArcelorMittal Orbit Tower (see previous page), the pointless cable car over the River Thames and the impractical (but beautiful – a Thomas Heatherwick design) new Routemaster bus all share Johnson’s lack of attention to detail.

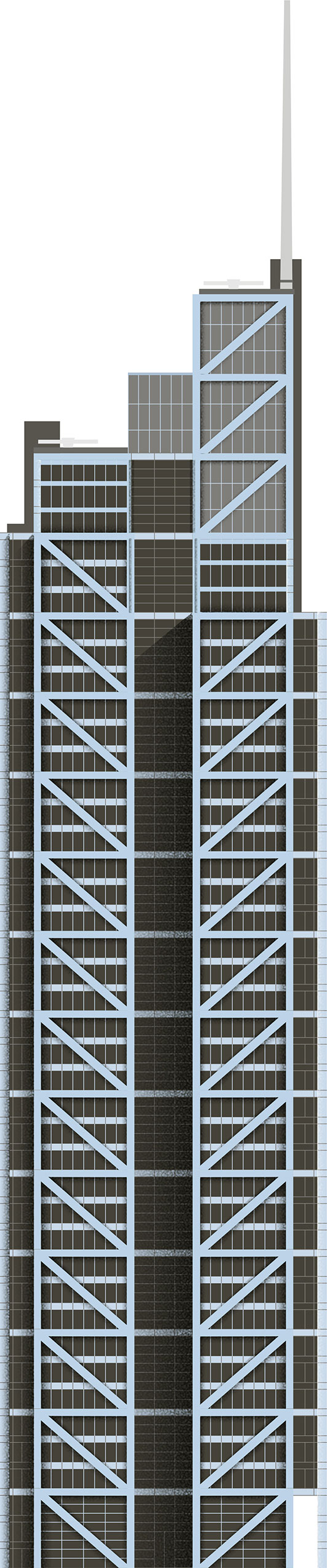

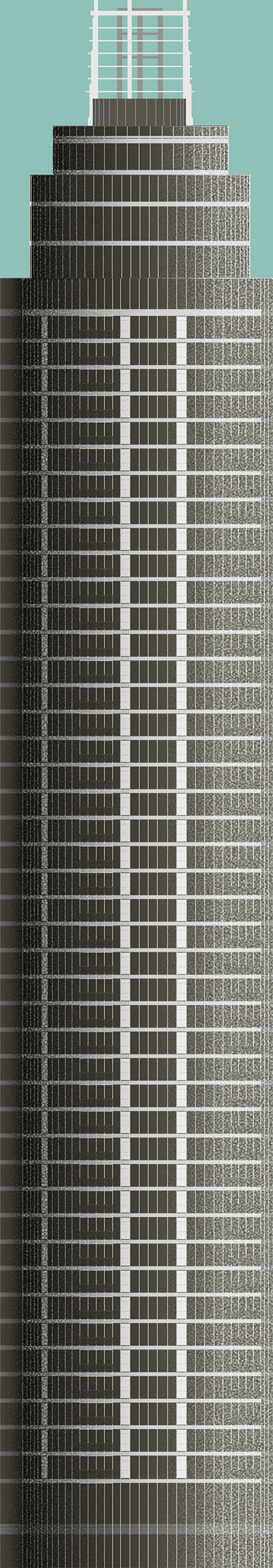

In central London, a new generation of skyscrapers, slowed down by the 2008 economic crash, arrived. Heron Tower (114) was originally designed in 1999, before the Gherkin (106) arrived and demonstrated the plausibility of skyscrapers in the City. It took years to get planning approval, mainly because of its proximity to St Paul’s Cathedral when viewed from Waterloo Bridge. The top of the tower was remodelled and approved, and the project was finally finished in 2011.

114 Heron Tower

Paul Simovic, Gene Kohn, Dennis Hill

2011

2011  EC2N 4AY

EC2N 4AY  230M

230M

It became the tallest skyscraper in the City, beating NatWest Tower (077) after an incredible thirty-one years at the top. The speculative development is made of two stacks of three-storey units, which are apparently an ideal size for letting. Seen from the north, these units are clearly distinguishable thanks to the structural bracing that frames each one of them. Unfortunately, the views from the other sides are less interesting.

Elizabeth Line

Originally known as Crossrail, this is one of the largest construction projects in Europe – a sixty-mile-long railway connecting London with western and eastern commuter towns.

Boris Bike

London mayor Ken Livingstone was so impressed with the bicycle rental system in Paris that he decided to copy the idea. It finally launched in 2010, when Boris Johnson was mayor, hence the unfair nickname.

Unusually, the core – incorporating the lifts and services – is not positioned in the middle of the structure, but along the southern edge. This solution helps to keep the office layout clear and uninterrupted. The core also shades most of the sunlight, often a problem for a fully glazed building, and so helps to reduce the use of air conditioning and electricity. Also helping out with the energy bill are 48,000 solar cells scattered around the southern façade. These were added to satisfy the London Plan’s requirements to derive a portion of the building’s energy from renewable sources.

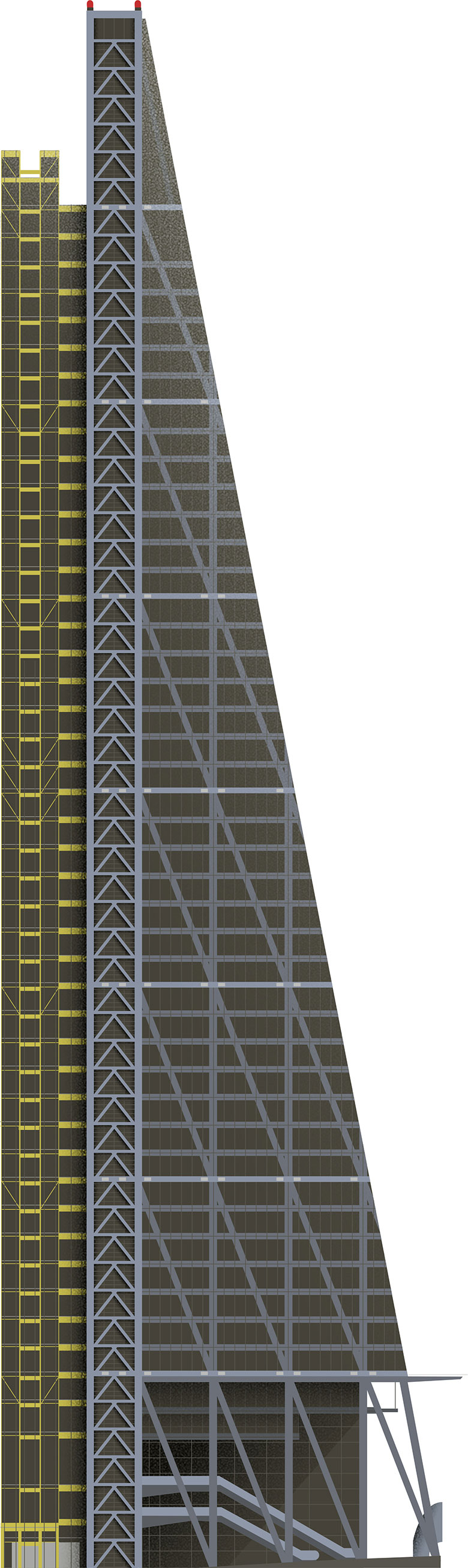

The financial crisis led to the cancellation of a number of large projects, but most of them were simply delayed. Graham Stirk of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (Richard Rogers renamed what had been Richard Rogers and Partners to demonstrate the importance of his partner architects) first sketched the Leadenhall Building (115) in 2001. A long fourteen years later, it finally opened. By then, it had already become known as the Cheesegrater. Like any other skyscraper in London, it was put under heavy scrutiny over its height and its potential for ‘spoiling views’. Seen from Fleet Street, the building had to lean away from St Paul’s in order to allow space for the view.

115 Leadenhall Building

Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

2015

2015  EC3V 4AB

EC3V 4AB  225M

225M

The outcome worked to the designer’s advantage, resulting in a very distinctive profile. The elegant shape, efficient engineering and superb construction details made the Cheesegrater one of the best new skyscrapers in London. Across the road stands the Lloyd’s Building (078), which the same practice had completed three decades earlier. The two buildings together show just how much architecture and the City had progressed during the intervening years. And although very different, both buildings carry a specific ‘house style’ – something few architecture companies ever achieve.

Wrightbus Routemaster

The brainchild of Boris Johnson, who wanted to bring back the Routemaster bus. The hybrid bus was designed by Thomas Heatherwick in a hasty process that led to a host of technical problems. The main feature, an open back platform that has to be manned, was abandoned for the same reason discovered forty years previously – it was expensive to have an additional member of staff at the back of the bus.

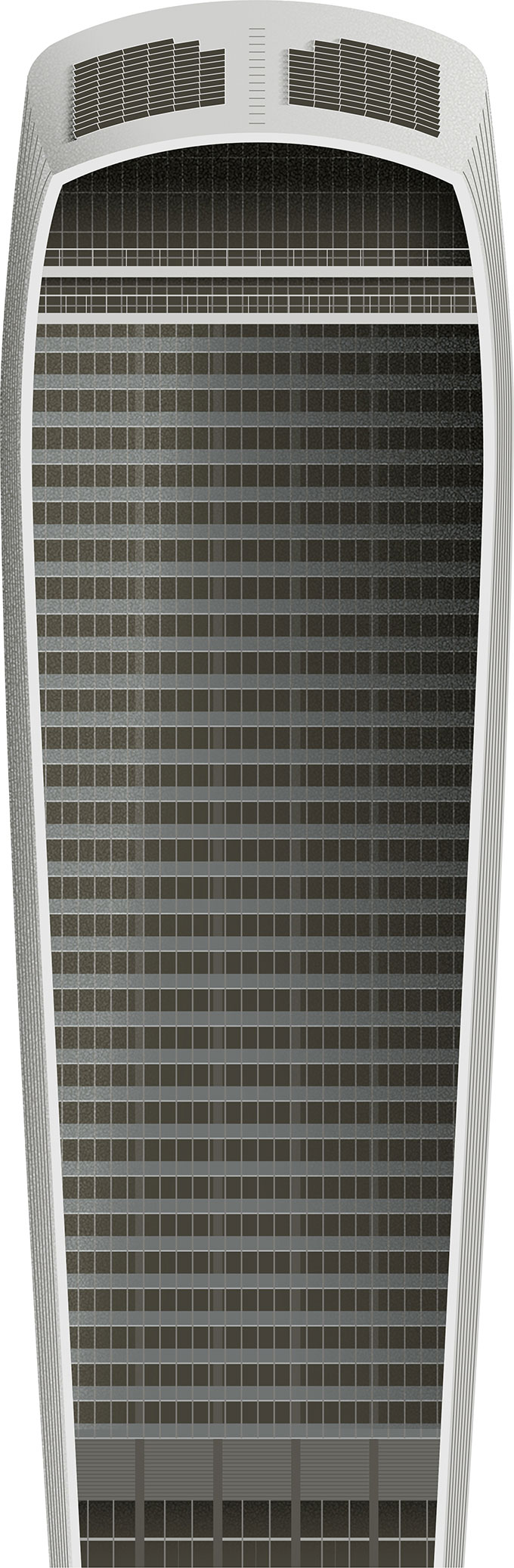

20 Fenchurch Street (116) was suitably nicknamed the Walkie Talkie due to its complicated shape; it certainly feels more like product design than architecture. The building, designed by Uruguayan Rafael Viñoly, got an unusual amount of press coverage, but for all the wrong reasons. As with other big (and problematic) developments, it had to ‘give something back’ in order to be approved by planners in the City.

116 20 Fenchurch Street

Rafael Viñoly

2014

2014  EC3M 8AF

EC3M 8AF  160M

160M

An impressive garden/observation deck accessible to the public (if you book three days in advance) did the job. In order to maximise the size of the most profitable floors with a river view, the building swells towards the top. This gives the skyscraper a rather unflattering, top-heavy profile. Its neighbours had to be paid off, to give up their right to light (see Broadcasting House (011)).

But what really damaged the building’s reputation was the ‘death ray’ created by its concaved south façade. The concentrated reflection of the sun’s rays was so powerful that it melted plastic parts of a car parked nearby. This was a recurring nightmare for Viñoly apparently – his earlier Vdara Hotel in Las Vegas had the same problem. The skyscraper, re-christened Walkie Scorchie, was later fixed with the installation of fins, which redirected the sun’s rays. The building went on to win the Carbuncle cup – an award for the ugliest building in the UK. However, the accolade did little to deter a Hong Kong buyer, who paid a record £1.3 billion for the building in 2017.

Cycle Superhighway

Protected cycle paths leading from suburbs to the centre of London are slowly being introduced, giving commuters a healthy alternative. Over half of all the traffic on Victoria Embankment during peak commuting hours is now cyclists.

Charging Point

Hundreds of chargers for electric vehicles are popping up around London in a rush to upgrade the infrastructure for the twenty-first century.

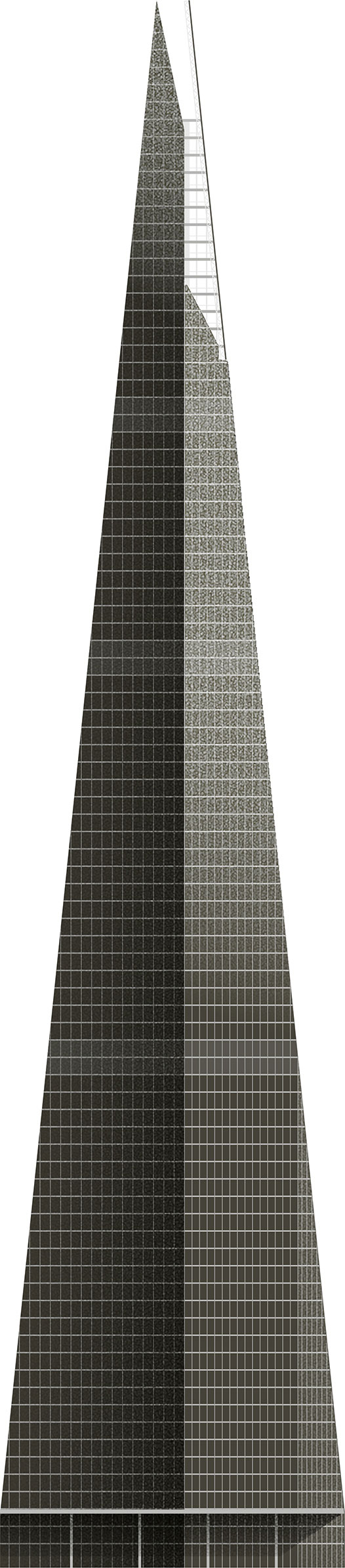

What happens when British developers team up with an Italian architect, Qatari investors and a Hong Kong hotel? The Shard (117) happens. At 310 metres, it became the tallest building in the European Union, although globally it’s not even in the top hundred – Europe never played that game anyway. The Shard stands over a major transport hub, London Bridge Station, and offers spectacular views of the financial district across the river. Its location, away from the two main clusters of skyscrapers, paradoxically helped it rise higher. Unlike in many cases in the City, no protected view corridors limit the site and, it’s not in the landing path of aeroplanes as is Canary Wharf.

117 The Shard

Renzo Piano Building Workshop

2012

2012  SE1 9SG

SE1 9SG  310M

310M

The design sees an elongated pyramid gradually break up towards the top. It’s a shame that the ground level is so underwhelming. As the style of this decade dictates, the tower is completely glazed. To reduce heat gain from the sun, the façade has two skins with a ventilated space between them, and automatically operated shades are of course a must. Still, the building is an energy hog. The lower floors are dedicated to offices, a luxury hotel occupies the middle space, and flats for the super-rich occupy the highest floors. The top floor contains a fairly expensively ticketed viewing platform accessible to the public. All ten ultra-luxury flats on top of the tower remain unsold, more than five years after opening.

In the twelve years that it took to design and build The Shard (117), the architect Renzo Piano contributed another building to London’s skyline. Born in Genoa, Piano became an architect of international renown, although his main office is still based in his home town. Early in his career, Piano formed a practice with Richard Rogers. Practically unknown and with not much experience, they went on to win the competition for the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, beating architecture giants such as Oscar Niemeyer and Philip Johnson. Their unconventional design was extremely challenging, and when the building was finished six years later, Piano and Rogers went their separate ways.

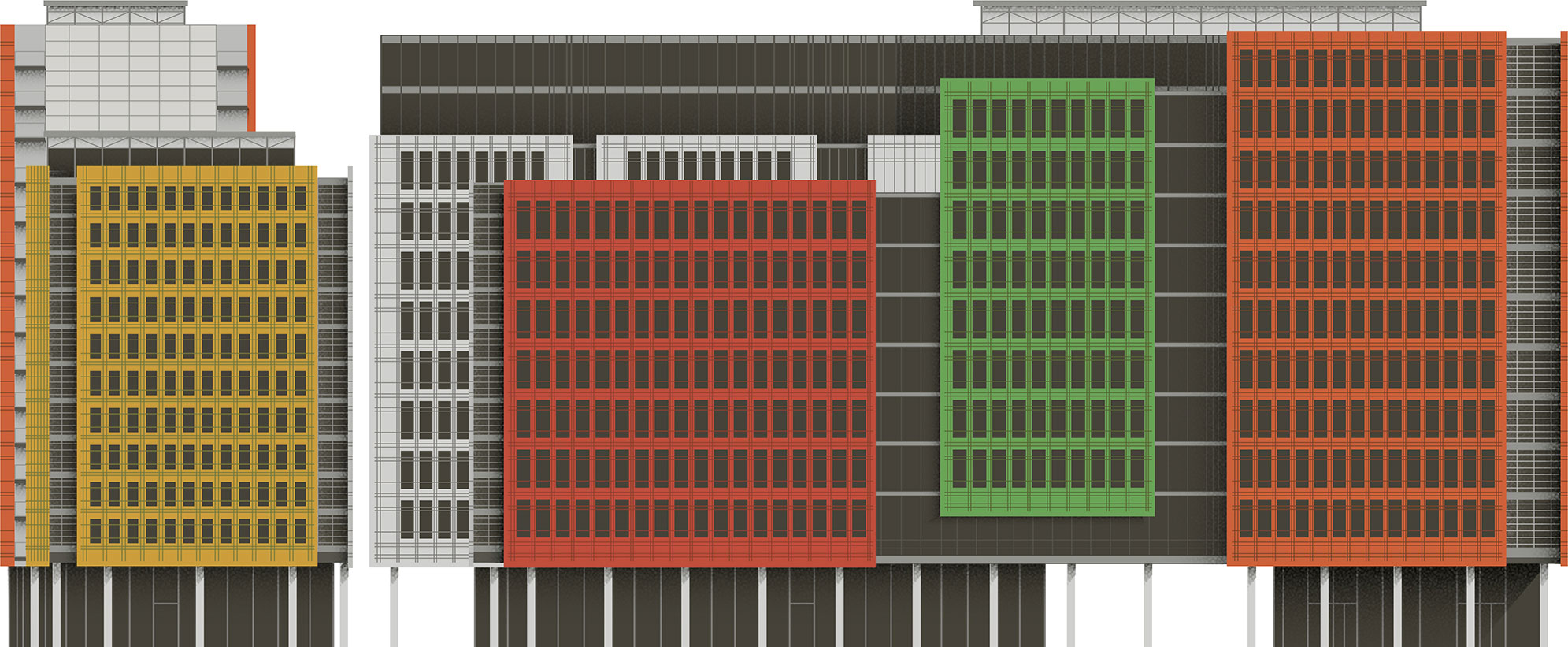

The building almost broke them, but it certainly put them on the map. Central St Giles Court (118) was built on an ‘island’ surrounded by busy roads, previously occupied by a 1950s office building. The architect introduced new pathways leading through the site, offering shortcuts to passers-by. The massive bulk of the new development is skilfully modelled by Piano, who employs every trick in the book to break it down to a scale more appropriate to the area. Blocks vary in height, the top floors are recessed and the façades form a rainbow of vivid colours.

118 Central St Giles Court

Renzo Piano Building Workshop

2010

2010  WC2H 8AG

WC2H 8AG

The terracotta tiles were originally made in Germany before being assembled into blocks in Poland and sent on to Camden for installation. It’s amazing how much of an international process construction has become, but it is similarly troubling – the CO2 emissions linked to these materials and their transportation must have been significant. See BedZED (110) for a more environmentally friendly approach to construction.

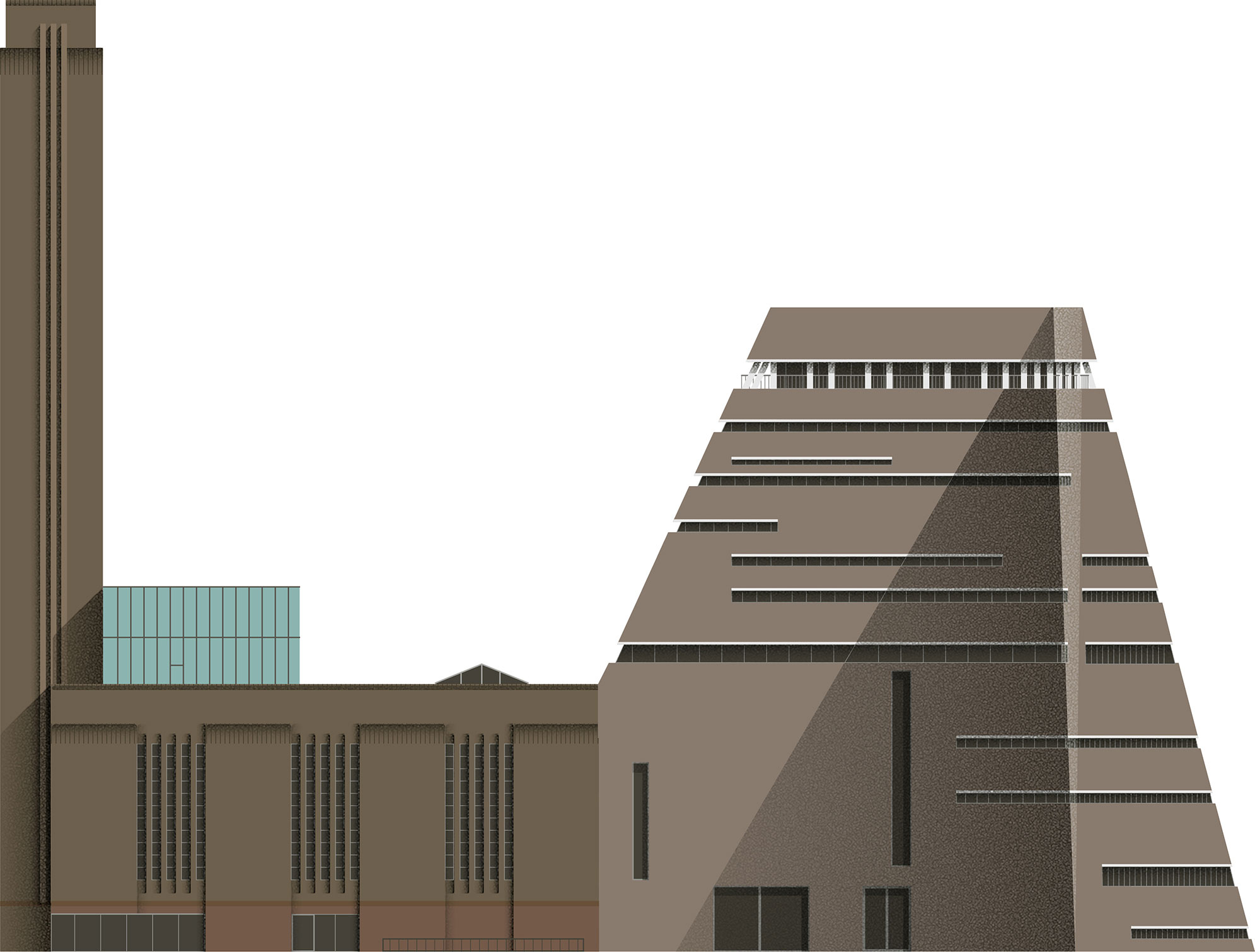

A victim of its own success perhaps, Tate Modern (103) was in need of more space practically immediately after opening. A solution was found in the form of the handsome Blavatnik Building (119). Herzog and de Meuron, architects of the original conversion, were called up again. The modesty of the original refurbishment was abandoned and they designed a bold and confident ziggurat to adjoin the original building. An initial proposal saw the building fully glazed, but after strong criticism from the public it was (thankfully) redesigned and now incorporates beautiful brickwork. The interior is finished in rather rough but suitably minimal bare concrete and wood.

119 Blavatnik Building

Herzog and de Meuron

2016

2016  SE1 9TG

SE1 9TG

And in order not to repeat previous mistakes, the new building includes an excessive number of elevators (whether this really helps is questionable; it’s impossible to catch a lift that doesn’t stop at every single floor!). One of its greatest features is a viewing platform on top of the building, which is, like the museum, free of charge. However, the neighbours may think otherwise – the owners of the flats in the expensive (and glass-walled) apartment blocks across the road have repeatedly tried to prevent nosy tourists peering into their million-pound pads.

Aeryon SkyRanger

The Metropolitan Police Service is now trialling drones for a wide range of uses: from chasing moped gangs to searching for cannabis farms. Its price is a fraction of the operating costs of a helicopter, but one might argue that it’s uncomfortably dystopian.

The economic crisis prompted only a momentary pause in the development of luxury flats. London, with its stable political position and rising property values, became a favourite investment spot for the global rich. A group that, according to Transparency International, included corrupt individuals looking to launder their money while enjoying a luxury lifestyle. Developers chasing high profits focused on delivering structures suitable for these big-spending clients. This, coupled with staggeringly high land values, raised property prices to levels altogether unreachable by the vast majority of locals. It remains London’s biggest headache.

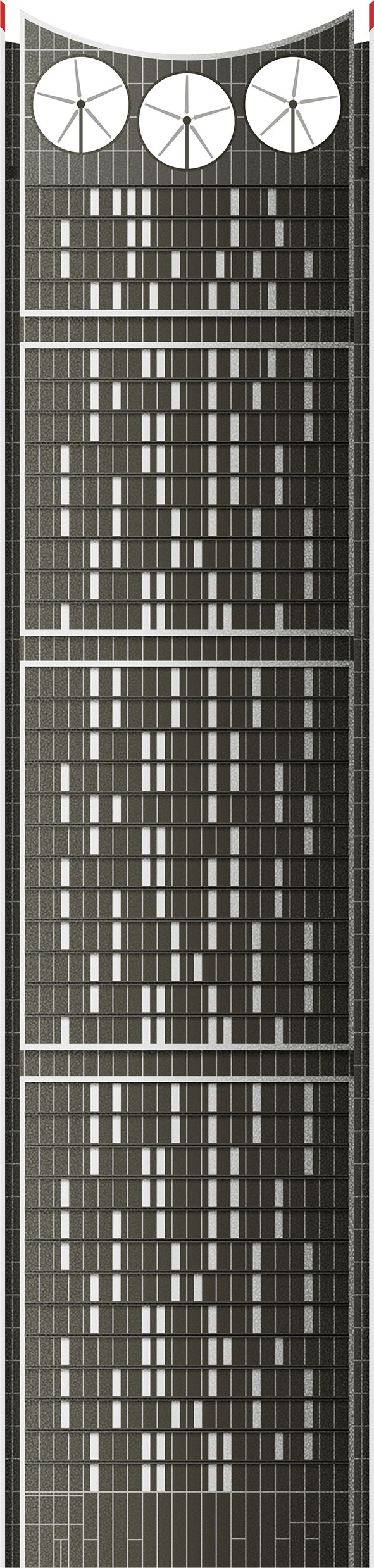

Strata SE1 (120) was the first step in yet another regeneration of Elephant & Castle (see here). The area, as with most of Southwark, has seen much controversial replacement of council housing by new flashy developments. The 148-metre-tall ‘Electric Razor’ was the first building in the world designed with integral wind turbines, which sit atop the wildly shaped construction. According to the plan, the wind would supply 8% of all energy in the building. But problems with maintenance and noise levels turned the wind blades into mere decoration. Since then, the building has become synonymous with ‘green-washing’, whereby architectural designs incorporate elements of green technologies without ensuring they actually work.

120 Strata SE1

BFLS

2010

2010  SE1 6EE

SE1 6EE  148M

148M

LEVC TX5

The electric taxi started replacing its dirty diesel predecessor in early 2018. Now, the biggest challenge for London is to build up new, city-wide infrastructure for recharging.

Toyota Prius

Londoners quickly adopted the Uber app after its launch in 2012, much to the dismay of black cab drivers. Unlike their new competitors, they have to go through extensive training in an attempt to commit London’s street network to memory (nicknamed ‘The Knowledge’).

St George Wharf Tower (121), or Vauxhall Tower, used similar tactics to ease its way through the planning process, also by placing a wind turbine on top (although this time, only one). The ‘glass cigar’ was originally rejected by planners but was later approved by the then deputy prime minister, John Prescott. It became the tallest residential tower in London. Two years after completion, The Guardian newspaper revealed that two-thirds of the luxury apartments were owned by foreign billionaires, many of them through offshore companies. Some of the names seemed to confirm the fear that London had become a deposit box for dirty money. Although now sold out, the building is practically empty, as most of the owners bought the flats only as an investment purchase or a holiday home.

121 St George Wharf Tower

Broadway Malyan

2014

2014  SW8 2AZ

SW8 2AZ  181M

181M

Agusta A109E

This helicopter tragically crashed into a crane working on St George Wharf Tower on a foggy morning in 2013, while attempting to land at London Heliport. The pilot and a pedestrian died on the spot.

In 2016, Londoners voted in Sadiq Khan as the new mayor – a human rights lawyer who proudly identifies himself as the son of a London bus driver. Quite a change from his predecessor’s Eton / Oxford background. To tackle London’s long problem with pollution, especially from diesel vehicles, Khan set up the Ultra Low Emission Zone in central London. From 2019, vehicles with older engines will pay an extra fee on top of the Congestion Charge. Controversially, all black cabs are exempt from paying, unlike ambulances or fire engines.

Khan’s toughest challenge is definitely the delivery of affordable housing, something both Livingstone and Johnson struggled to do. His new plan supports councils and housing associations in the building of new housing stock. Councils are now forced to rediscover their role as a developer, something that was abandoned four decades earlier (see here). Housing can be delivered by as much as a third cheaper when directly developed by the council, cutting out the middle man. There is an increasing number of architects who shun working on commercial projects and now focus on working with the councils.

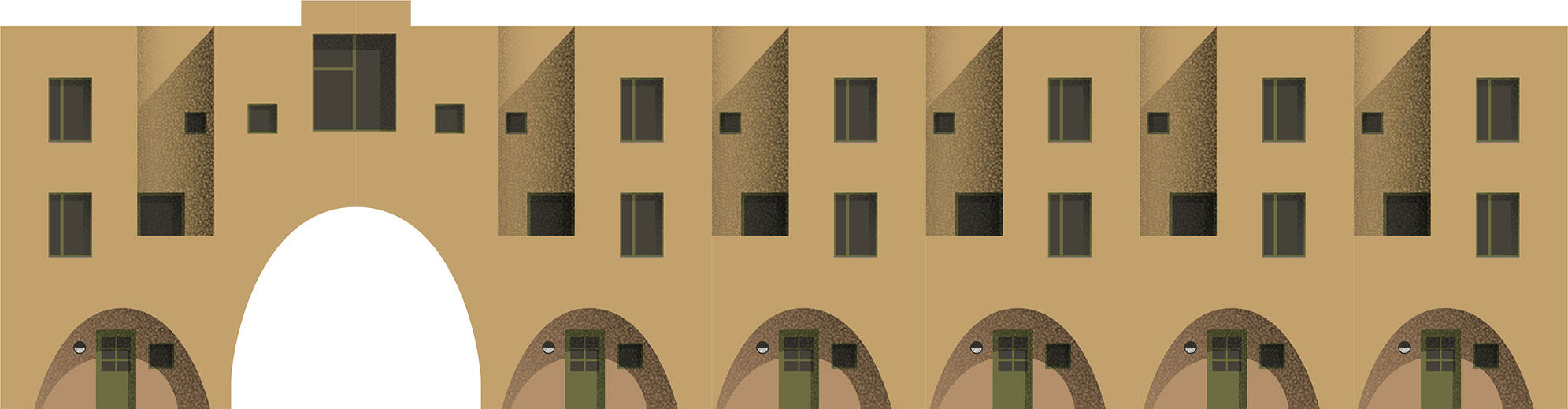

Peter Barber is one such example; he has delivered affordable housing on different projects all around London. On a small site down a dead-end street in Stratford, he designed a row of terraced houses in association with Newham Council. Worland Gardens (122) is a simple yet playful building that pays respect to the surrounding Victorian terraces, while being unmistakeably modern at the same time. These six townhouses are designated as shared ownership, where residents own a part of the house while the council owns the rest. This helps people who can’t afford owning the whole house to get their foot on the property ladder.

122 Worland Gardens

Peter Barber Architects

2016

2016  E15 4EY

E15 4EY