CHAPTER 8

The Outcome: Assessing the Rivalry De-escalation Theory

In Chapters 1 and 2, we presented and developed our argument that some types of interstate rivalry terminations can be explained with a small handful of variables. It was noted that a respectable number of rivalries terminate simply because one or both sides acquiesce to the superior strength of their adversary. They are beaten in wars, eclipsed by transition dynamics, or simply are forced to acknowledge that they are unable to maintain their competition. In other words, they are no longer in the same league. These rivalry terminations are not difficult to explain. Other rivalries, however, cannot be explained by coercion, subordination, or surrender. This other class of rivalries is subject to negotiations and decisions to de-escalate. Our model is designed to encompass this other, less coercive category.1

The model focuses on the revision of one or both sides' expectations about the other party. Since interstate rivalry is predicated on the perception of competitors that are also threatening enemies, the revisions tend to focus on downgrading the perceived degree of threat or enemy status. Changes in expectations do not necessarily mean that one's rival is suddenly embraced as a friend or ally. Negative images are likely to persist. But, the discernment of decreased threat or enemy-like behavior, in conjunction with a small set of additional variables, can lead to the termination or significant de-escalation of a rivalry.

Expectational change, while essential to our argument, is not sufficient. We think some mixture of the following is needed to bring about voluntary de-escalations. In addition to the expectancy revisions, shocks are needed to overcome the pronounced tendency toward foreign policy inertia. The more ingrained the inertia, the greater the shock or shocks that need to take place. Policy entrepreneurs can certainly help organize support and lead in overcoming previous stances taken toward a one-time enemy. Third-party intervention may also help this process of change gain and maintain momentum, perhaps through the provision of resources and protection—or the threat of withholding one or the other commodity. Yet neither policy entrepreneurs nor third-party intervention are essential. They can facilitate the policy change, but they do not appear to be absolutely necessary. More critical to the outcome, we think, is the need for an adversary to reciprocate any concessions offered and to continue reinforcing the other state's decision to move in a different policy direction. In the absence of reciprocation, little in the way of progress can be made in revising how states treat each other. Once some progress is made, de-escalating rivals need to continue avoiding behavior that will alarm their adversaries and give grounds for setting back the movement toward de-escalation.

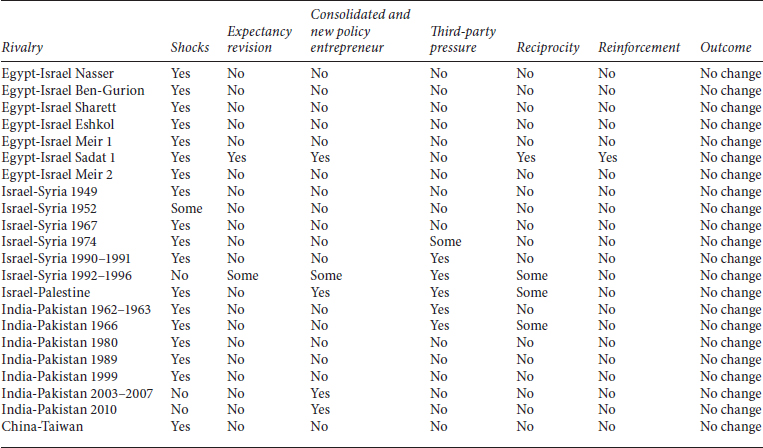

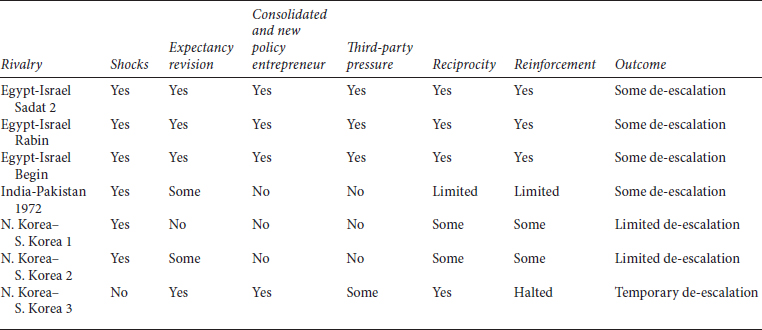

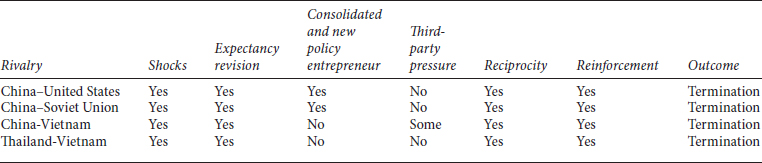

Our argument is reasonably parsimonious and, more importantly, testable.2 How does it fare when the argument is confronted with some thirty-three Eurasian cases with different outcomes (within ten rivalries) that have been described in Chapters 3 through 7? There are definitely ways to analyze thirty-three cases in the aggregate that are more sophisticated. However, we find the outcome to be unusually clear in its pattern—so clear that sophisticated methods hardly seem warranted. Instead, we break down the outcome into three groups and tables. The first table (8.1) examines only the twenty-two cases in which the rivalry experienced no change. Two additional tables focus exclusively on eleven cases in which some de-escalation was achieved (seven cases in Table 8.2) or termination was accomplished (four cases in Table 8.3).

Table 8.1 summarizes the outcome associated with cases in which most of the relevant explanatory variables should be recorded as absent. In all but one column, the collective values of the variables are 80 percent or more absent. The nonconforming column pertains to shocks, which are quite common in Table 8.1 (86 percent). By and large, then, it should be clear that shocks are simply opportunities at best. It depends on whether anyone is willing or eager to exploit them. In Table 8.1, the “no change” cases were situations in which some effort was made to consider de-escalation. In most cases, only the shock column registers a positive value. With but two exceptions (Egypt-Israel, Sadat 1; and Israel Syria, 1992–1996), the other positive values are scattered in situations in which only one or two of the six explanatory variables are coded as positive. The Sadat 1 exception is an asymmetrical situation. Sadat was prepared to negotiate in the early 1970s but his Israeli counterparts were not. The “solution” was to create a new shock in the form of the war of 1973, which brought with it the additional bonus of third-party diplomatic intervention. The second exception lacked a shock that might disrupt foreign policy inertia. None of the other values, and especially the strong mistrust associated with both sides' expectations, was strong enough to bring about de-escalation in the absence of a shock or shocks. Table 8.1 thus passes our first test quite well. The rivalries that did not de-escalate significantly have been predicted as not changing much by our model.

Table 8.2 isolates the cases in which some de-escalation was experienced. In this situation, we should expect a fairly high proportion of positive scores for the explanatory variables. Since the outcome is “some or limited” de-escalation, there is no reason to anticipate the variables to be present at full strength. Something should be missing.

One possible pattern is a block of cases with some present “hits” on some but not all variables. Another possible pattern involves some cases with a strong array of predictors being present and some with a mixed but less than full array. It is the latter that is demonstrated in Table 8.2. The first three cases listed in the table show the presence of all six variables and some de-escalation. The other four instances include one Indo-Pakistani episode and three Korean cases. All seven instances represent hard cases of strongly entrenched rivalries. In each case, there was substantial resistance to full termination, albeit variably manifested especially in the Korean cases. In the Egyptian-Israeli case, the movement toward de-escalation went only so far. A “hot war” environment moved to a “cold peace” era without fully ending the rivalry. Momentum toward de-escalation in the Indo-Pakistani case has never proceeded very far. In the case of the two Koreas, substantial progress was made toward de-escalation after a couple of false starts until a change in regime in South Korea elevated to power a more conservative group that had always been less inclined to reinforce the process of de-escalation. In that respect, the Korean case resembles the Israeli-Palestinian one.

What seems most important about these cases is that there were limits to the degree of expectancy revision achieved. The Egyptians and Israelis still regard each other as strategic rivals. What has changed is that a combination of U.S. intervention and substantial foreign aid, Israeli security preferences, and Egyptian development preferences came together to foster an agreement not to threaten each other with war once Egypt regained its lost territory. As long as Egypt remains outside of a possible attacking coalition, Israeli security is improved because a conventional Arab military attack is unlikely without Egyptian participation. Thus, the Egyptian-Israeli de-escalation is a very special case.

Table 8.1. The Summary Empirical Outcome: Rivalries Involving No Change

Table 8.2. The Summary Empirical Outcome: Rivalries Involving Some De-escalation

The Indians and Pakistanis, so far, have not had much reason to change their respective evaluations of their adversary's intentions or threat potential. The nearly decisive defeat of Pakistan in 1972 might have led to a situation in which rivalry termination was related to a defeat in war—the category our model is not trying to explain. But the basic issues at stake, especially Kashmir, did not go away and were revived by independent events in Kashmir and not in Pakistan. At the same time, the perceptions of the two rivals of their adversary have never altered all that much. Once the Kashmir revolt was renewed by Kashmiris, the Indo-Pakistani rivalry was back on at full strength again.

The Korean circumstances are different. The first attempt at de-escalation was not accompanied by any expectancy revision. The next one involved some (at least in the south) and the third was predicated on considerable change on the part of the South Korean government. The problem was that there was no guarantee that the attitude of the South Korean government would remain the same after several subsequent elections. Another way of putting it is that progressive/liberal expectancies about North Korea changed substantially while conservative expectancies changed less. No one seems too sure of what North Korean expectancies were or to what extent they changed. But as long as progressive/liberal governments remained in power in South Korea, rivalry de-escalation might proceed. Once a conservative regime gained power in the south, the rivalry returned to its old format of intermittent North Korean attacks on South Korea.

Four cases of full termination are listed in Table 8.3. In this test we should expect a high proportion of positive values. The predicted four of the six explanatory variables are associated with “perfect” outcomes in terms of our four core variables. Shocks, expectancy revisions, reciprocity, and reinforcement are all present in the termination cases. Presumably, they are all necessary, as we have predicted, although none alone is likely to be sufficient. Policy entrepreneurs and third-party intervention, however, are sometimes present and sometimes not. We had thought initially that policy entrepreneurs and third-party intervention could be extremely helpful but that neither was absolutely necessary. That expectation seems to be supported in Table 8.3. In some cases, these two variables may have been essential.3 But, in general, they do not seem to be as crucial as the hard core of the four critical variables.

Table 8.3. The Summary Empirical Outcome: Rivalries Involving Termination

What these findings add up in terms of our model is rather strong support for the combined presence of shocks, expectancy revision, reciprocity, and reinforcement. Other factors, such as policy entrepreneurs and third-party intervention, are less critical to the outcome. Still, our model is meant to be highly parsimonious. It does not, for instance, attempt to capture regional landscapes (Chapter 7) per se that may also work toward or away from rivalry de-escalation. The comings and goings of major power rivalries or, for that matter, major powers, tend to have reverberations for rivalries involving minor powers. These “earthquakes,” of course, can appear in the parsimonious model as shocks for rivalry relationships. But the basic point to be stressed here is that rivalries are not maintained in dyadic vacuums in which all the important factors that drive rivalries are endogenous to the protracted conflicts.

We have few studies that examine systematically the transition of protracted conflicts from escalation to de-escalation. Of those that have, none have examined the transition more thoroughly than Kriesberg's studies (1998, 2007). Not unlike the approach herein, Kriesberg (1998) argues that de-escalation occurs as a result of changes in the conditions that underlay the emergence of a conflict in the first place and sustained its escalation. He goes on to say, however, that de-escalating transformations are long, cumulative processes. They are not brief, clearly delineated events. The shift toward de-escalation is produced by pressures building over time. If there are astounding moments of change, then they usually follow from many less visible trends (Kriesberg 1998: 190). In short, the de-escalation of intractable conflicts is not necessarily the result of immutable, large-scale forces or of the actions of a few brave individuals. Many circumstances need to converge and these must be interpreted in new ways in order for intractable conflicts to move toward de-escalation (Kriesberg 1998: 216–217). Only in retrospection can we discern a long-term transformation toward de-escalation (Kriesberg 1998: 24).

Our model would not disagree with many of the points made by Kriesberg (1998). While we would agree that changes in macro-conditions must converge with new interpretations, we do not necessarily support the notion that transformations always entail long-term processes or that their effects have to be cumulative over time. On the contrary, change can occur quickly and be observable almost immediately. This is especially the case when environmental crises affect the political survival of policymakers. In these instances, leaders have strong incentives to change their strategies and policies quickly. Although the shifts in their strategies or policies may not generate immediate outcomes of conflict termination, they can move protracted conflicts in new directions in relatively short periods of time. Our perspective leaves open the possibilities for short- and long-term effects because the analytical effort is not to explain the precise moment at which conflicts end but rather the process by which protracted conflicts eventually end.

However, an expectancy model does not have to be so imprecise that it cannot pinpoint moments of change. Political shocks tell us where the important turning points will or may be; they delineate the moment at which decision makers are more likely than at any other time to reevaluate their expectations, strategies, and policies. Without the environmental challenges that shocks pose, inertia overrides the inclination of decision makers to pursue new, risky policies that could undermine their positions. Therefore, expectancy models are indeed historically contingent, but they are not so idiosyncratic that we cannot specify generalized patterns of behavior across many varied cases of protracted conflict. Moreover, the interactions between shocks and expectations are hardly the end of the de-escalation process. Rather, it is merely the beginning. The question then concerns what actors and actions are critical to keeping the de-escalation process in motion.

It is always gratifying to learn that a parsimonious model works reasonably well. That means little expectancy revision is needed on our own parts. We found that policy entrepreneurs were useful but not as critical as expected. We also found that third-party intervention could be useful, but, as expected, it was not necessary either. Yet it should be kept in mind that we initially restricted our analyses to Eurasian rivalries. The reason for this is that we view Eurasian rivalries as roughly more similar in nature than the full universe of rivalries. Sub-Saharan African rivalries tend to be focused on ethnic affinities and governments interested in how domestic groups are treated by adversaries. Latin American rivalries are not totally unlike Eurasian rivalries in their preoccupations with quarrels over contested territory, but they have a propensity to endure for long periods of time with fluctuating levels of intensity. Eurasian rivalries fluctuate in intensity as well, but their lower levels of hostility never seem to dip as low as many Latin American rivalries have done.

We make no claim that these differences hinder or block the application of our termination model. Our decision to focus on Eurasian rivalries exclusively was based solely on convenience.4 There was a possibility that the differences might matter. Equally or perhaps, truth be told, more important, we were more comfortable as authors working with Eurasian rivalries. Detailed information on sub-Saharan African foreign policy is quite difficult to attain. Spanish-language sources would be very helpful in the Latin American cases and it is a language skill none of us possess.

Consequently, we would like very much to see the model applied to Latin American and sub-Saharan African cases. There are also a number of older European rivalries (and some newer ones) that deserve analysis as well. The model was designed to be as general as feasible. Our testing has not yet caught up to the generality of the model. Hopefully, that will change. But there is also a significant exception to our Eurasian sample. Of course, we did not examine every possible Eurasian rivalry. We fully expect that there is more useful work that can be done in looking at rivalries that we chose to ignore. There is also the 800-pound gorilla of rivalry termination cases, the U.S.-Soviet Cold War, which is more Eurasian than anything else. We balked at including that rather significant rivalry in this study because it would no doubt require detailed analysis entirely on its own. The many controversies associated with disputes about what brought about the de-escalation of the Cold War are strong and the details are too numerous to deal with in a chapter or two. At the same time, we are confident that the rivalry termination model that we are advancing should work well in the case of the Cold War. It is fair to say that it would have been impossible to formulate the de-escalation model without at least thinking about the nature of the prominent Cold War rivalry. Our confidence that the model should work to explain the end of the Cold War, nonetheless, needs explicit testing.

Finally, there is one other arena of possible application that we have yet to explore. This book focuses almost exclusively on protracted interstate conflicts. There are also a large number of protracted intrastate conflicts. We doubt that our interstate rivalry model can be applied to intrastate rivalries without some modification and/or elaboration, but at the same time, we think that domestic applications are more than merely conceivable. The logic of rivalry de-escalation should be fairly generic. One way to test this assumption is to try applying the interstate model to intrastate situations.