15 Approaching specific interest markets

The value and significance of the niche in publishing

Finding the general reader

Marketing children’s books

Opportunities for children’s publishers today

Key difficulties for those marketing children’s titles

Marketing techniques for promoting children’s titles

Selling resources to public libraries

How to send information to public libraries

Public lending right

Promoting to university academics

Promoting textbooks to the academic market

Summary books and study aids

Research monographs

Professional resources

Selling to academic libraries

Selling to educational markets

How to reach the market

Selling educational material to international markets

Marketing to doctors and other healthcare professionals 410

How to communicate effectively with doctors

When is the best time to promote to doctors?

Other opportunities for publishers in this area

The role of medical librarians

Selling to professional and industrial markets

Important information for approaching professional markets

Format of published and marketing material

All definitions of marketing agree on the importance of the customer, and in order to approach them in an appropriate manner – to be able to identify the products, services, offers and marketing messages that are most likely to appeal to them – it’s vital to understand who they are. This chapter therefore offers a more detailed exploration of several markets that are particularly important to publishers.

For those working in some areas of publishing, without a specific background or understanding of the market, this may initially feel difficult. We will therefore begin with a few general principles before moving on to examine some particular markets in more detail.

• Begin with an enquiring mind. Whatever your level of understanding, and however specific the area you are now approaching (e.g., medicine, dentistry, engineering), you need to begin with curiosity. All marketers need to be fascinated by their customers: the range of products they buy; how they choose; how and why they need them and through what means they pay. It’s your job to be interested and involved rather than think how unusual or odd they are.

• Find out all you can about them. Read the publications and blogs they read and examine the websites they frequent. If they have meetings, national or regional, try to attend one; observe them in action and watch how they behave. Look out for general trends: how do they speak to each other; what do they wear; can you generalise about their demographics; how diverse are they? Even if the subject of professional interest is completely new to you, what tone of voice is used in the correspondence or vacancies sections of the forums they use?

• Approach with caution. Observe rather than speak; store away information to fuel your understanding of the group you are required to work with and note key words in order to reflect them back later on. Bear in mind that, lacking information to the contrary, the market will probably assume you care as much about their profession/specific interest as they do. Say little until you feel you can contribute without letting the side down:

Better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to speak and to remove all doubt.1

• Feel confident. You bring objectivity. Lack of experience, provided it is managed in an appropriate way, can lead you to ask the right questions about products and services and how they benefit the market, avoiding the peril of assumption that may have fuelled past approaches and led to lost sales. There is a real danger that the reasons the publisher or author gave when planning to offer a product or service may not be the same as those relied on by the market when deciding whether or not to purchase. Your insight in exploring such gaps may be really valuable.

Case study

The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook (Bloomsbury) has been published annually since 1907. It offers a compendium of names and contact information for those wanting to get published or sell their work, and a range of relevant articles from key figures in this field. It is also a book that gets widely used within publishing houses, the names and address sections providing a valuable, and regularly updated, address book for anyone wanting to contact the media or find new professional contacts. Publishers, however, tend not to read the articles – being fully involved in the profession, they do not need to read about how to find an agent, or how authors can best manage their marketing. Year-on-year the book has expanded in size and, in order to keep it to a manageable length, the publishers were considering which parts of the book could be trimmed. Before doing so, they commissioned some market research into how the book was used.

A questionnaire was included in all titles sent out from the publishers’ warehouse and lodged with booksellers willing to cooperate, and who could be persuaded that this was not an attempt to get people to order directly. The conclusion was that the main market (writers) liked to read the articles and did so long before they got around to using the contact information in order to target those who might help them get published. In other words, the main reason the publishers found the book useful was not the same as that of the market.

Finding the general reader

When approaching specific professional markets, it’s relatively easy to understand your audience – you locate the relevant professional journal or forum, observe what’s going on and start building your knowledge. More general markets are much more difficult to understand – members could be anywhere.

The advance information produced by publishing houses often lists the target market as the ‘general reader’ or sometimes their more cultivated counterpart, the ‘educated general reader’. To start with, it’s a very unspecific term, and the segmentation of markets into smaller, more manageable groups through demographic analysis or lifestyle stages may include general readers in every category. How can we be more precise?

This book will be available worldwide, so providing specific and local guidance to markets close to every reader is impossible. It’s therefore important to emphasise the value of keeping track of what is going on in society as a whole, of remaining observant. You need to remain alert to a variety of different viewpoints, and the number of people they represent; to move beyond your own comfort zones and assumptions.

It’s important to consult a variety of websites and blogs; to read a range of different newspapers and magazines; to watch and listen to a variety of television and radio stations – and above all to listen to people talk about the concerns they have. Watching soap operas or observing which major films are coming out (and which ones are successes) are effective ways of keeping track of current trends in society and learning to interpret them. Growing older can help too – provided we are stimulated by change rather than resistant to it – our ability to spot what’s going on around us, and newly emerging markets, becomes more acute as a wider range of things happen to us. So remain alert to what is going on in your life, and in those around you, how the experiences feel and what opportunities you spot for presenting published content in the process. As generalisations, and to get you started, here are a few current trends:

• Shortage of time. Time famine is established worldwide, and various forms of rage are now itemised as proof of how much we hate waiting (‘road rage’, ‘trolley rage’ and now ‘car park rage’). To get more done in the time available we multitask, often with several screens in front of us at the same time: texting while talking and surfing the web while chatting online. This does not mean that everything has to be achievable super-quickly, but if you are going to ask for an audience’s time, make it sound like an experience they can justify, both to themselves and their wider circle of influencers/responsibilities.

• Desire for better experiences – in friendships, relationships, conversation – often fuelled by a belief that these are our right. A desire for deeper, more fulfilling encounters often seems to be accompanied by restlessness; a greater desire for things to be better, yet a reduced tendency to work at them to make them so – or blaming/suing others if we are less than fully satisfied.

• Optimism. There is a big appetite for stories that distract, lift and show a positive spin on life, hence the many popular formats through which celebrities can announce their relationship/baby/marriage/new life after divorce with lavish pictures and supportive text.

• Curiosity. We like to read about ourselves – or those we can assume represent us – in publications that highlight the oddities of everyday life; disasters that have befallen people, how it feels to live through a situation or dilemma we may later face too.

• Competitiveness. This is now imbued into all levels of society, from stories of children being given additional academic tuition to help them pass exams earlier and earlier into their lives to beauticians offering better outcomes through a variety of procedures. Advantage is purchasable and reading about it expands the understanding of options.

• Brands. As society becomes increasingly international, there is increasing demand for badges that signify specific attributes (style, money, membership) and work across national and cultural frontiers.

• Respect. The internet coaxes the individual into relationships, offering us attention, understanding and an idea that our individual needs will be met. This spills over into how we expect to be treated in our daily lives and fuels intolerance and resentment if we feel we are not being treated as we should be. Our decision to move on if we don’t like the prevailing tone of voice can be instant (think how speedily we leave websites that get it wrong) and young people are often quick to claim that they have been patronised.

• Concern about the environment. This is growing very fast, steered by environmentalists, encouraged/blocked by politicians and championed by children, who are putting pressure on the generations above them.

All these trends create opportunities for promoting and selling products and services, and published products can be strong beneficiaries. But marketing messages need to be made specific and relevant to anticipated audiences, so it’s important to think through the market characteristics and the benefits they are likely to be looking for from the product or service you are developing and where it might be convenient to buy. There will usually be many options. So, for example, a home subscription to an online encyclopaedia could offer:

• A reliable and constantly available support for your children’s homework, answering questions you cannot (shortage of time).

• An authoritative research tool to ensure you are able to quote reliable information to those who may look to you for a professional opinion (competitiveness).

• A fascinating distraction (optimism, curiosity).

• To mark the owner’s home as a place that values quality (brand).

• Ease of access. Installation of the product has not required trees to be cut down, delivery lorries to pollute while offloading, or new storage solutions (concern for the environment).

The messages you choose will depend on the markets you are approaching, how big they are and how busy; how much extraneous noise you have to rise above in order to be heard. You need to consider the vast range of alternative distractions on offer that were not (or not widely) available 10 years ago. For example, people spend time and money on the internet, talking to others, information seeking and in online games, and the customisation that is now available for viewing and listening means they can make a personal timetable rather than be forced to rely on the broadcaster’s schedule. In response, remind them how reading feels: the one-to-one personal engagement with a mind they admire or story that engrosses them.

In addition to remaining alert to customers’ interests and buying habits, it’s a good idea to build their appreciation of what you offer, to understand your brand. Tell your customers a story and they may buy into it, feeling they have discovered something worth supporting. Tell them how you came to establish the firm, say what you did before; even better if you left a corporate lifestyle to publish or sell what you care about as quality of life and work–life balance are issues that many can relate to. The stories you share may spread quickly – it used to be believed that customers required years of good service before they would start recommending a supplier, but recent research2 has shown that there is a strong taste for the new and enthusiasts tend to pass on the name of their latest find immediately. How quickly can you start turning those who buy from you into advocates?

Top tips for turning your organisational brand into a community that other people want to belong to

• Share your vision for your organisation and its future; describe how you came to set the company up and what motivates you to do what you do. Tell the story.

• Have a visitors’ book on your website to allow people to record their thoughts (most people like to see their name quoted and may make the link further available through social media).

• Similarly, host a blog or chatroom on your website to create a sense of community; encourage (mediated?) feedback and post news and replies to show that you respond.

• Encourage enthusiastic correspondents to add their comments to Amazon and other book review sites.

• Where relevant, offer reading copies of new books for book groups.

• Make occasional offers of free copies, run competitions and prize draws either through your mailings or on your website.

• Offer proof copies to selected people to encourage them to ‘talk you up’.

• Most publishers send out manuscripts for review before committing to print. Widen this to form a reviewing community and enc0ourage feedback. Then print the names of those involved in a special section within the book. Not only will this spread ownership, if the reviewers are children this can prompt lots of additional sales in schools and among grandparents, parents and other encouragers.

• Offer branded goods that relate to your products, such as T-shirts or associated stationery (postcards, posters). You can test the market with a single item, and if there is positive feedback, produce more. This was how Penguin’s highly successful T-shirts of ‘paperback originals’ were born. Initially produced for distribution to sales representatives at the seasonal briefing conference, they were found to have a far wider appeal and are now successfully sold through bookshops. The product range has been expanded to include deckchairs and mugs.

• Produce information sheets, whether web-based or printed for specific needs – for example, for book groups; guides to terminology or key place names for saga/fantasy addicts; bookmarks and window stickers for distribution through reps and shops.

Case study

How an organisation can enhance its image with an effective brand: the Society of Authors’ new branding, 2013

The Society of Authors3 is a trade union for professional authors with more than 9,000 members, writing in all areas. It advises members on rights, fees or any other professional query. It also provides training, lobbies for authors’ rights and administers a wide range of grants and prizes such as the Authors’ Foundation, one of the few bodies making grants to help with works in progress for established writers. It acts as literary representative of the estates of a number of distinguished writers including George Bernard Shaw, Virginia Woolf, Philip Larkin, E.M. Forster, Rosamond Lehmann, Walter de la Mare, John Masefield and Compton Mackenzie. The society’s influence is widely noted within the publishing world and beyond – the organisation has more than 17,000 followers on Twitter.

To mark the arrival of Nicola Solomon, their new chief executive, the Society of Authors changed the text colour on their standard letterhead from blue to green. This was both an effective (and extremely low-cost) way of marking the end of an era, but also outlined a longer-term future ambition. From the outset Nicola, a former partner at a high-profile legal firm, was keen to standardise the society’s communications, make them fresh and accessible to ensure that both their membership and the wider range of those who could similarly benefit understood the range of services and expertise on offer. There was also determination to reach out to potential younger members and encourage them to join – and to acknowledge the wider range of situations in which writers are writing and needing support. Finally she was keen to affirm the organisation as a whole, which was started in 1884. Early supporters included George Bernard Shaw, John Galsworthy, Thomas Hardy, H.G. Wells, J.M. Barrie, John Masefield, E.M. Forster and A.P. Herbert, to name but a few. The first president was Lord Alfred Tennyson and George Bernard Shaw said of the new organisation: ‘We all, eminent and obscure alike need the Authors’ Society. We all owe it a share of our time, our means, our influence.’

While the initial task was to produce a new organisational brand, in the longer term this was to be far more than just a rebranding exercise. Nicola was clear that this was the launch pad for an exercise in appreciating the range of the organisation’s activities and understanding them as a coherent whole, and developing and promoting a wider understanding of its usefulness. She was keen to ensure a greater harmony in communication: in typefaces, presentation and tone of voice; this not to diminish individual contributions but to ensure that the membership is conscious of the organisation and that staff benefit from all the opportunities to absorb information from each other. Her only stipulation was that she wanted the brand eventually selected to be text and not image-based, having had experience of how images tend to attract and then polarise opinions.

The starting point was to find a firm with expertise in organising branding and through talking to other relevant organisations that had been through a similar experience, they found Brandguild.4 This was a specialist branding agency that had previously worked with organisations of a comparable size and ethic – and whose quotation for the work involved came within the agreed budget of £10,000.

Brandguild were appointed and began by doing some research among the members of the Society of Authors. Those chosen for interview by the society were from a variety of ages and writing genres, and Brandguild also talked to others who regularly interact with the organisation (publishers, agents, retailers) and those who could belong but don’t yet. They were asked about how they saw the organisation, what it was good at and not so good at – and what they called it. Interestingly whereas staff tend to refer to the organisation as ‘The Society’, members generally call it ‘Society of Authors’ or ‘S of A’.

The next stage was for Brandguild to facilitate a ‘creative day’ for all staff, and in the process to find out from those who are most aware of the services offered by the organisation how they feel it is currently understood and appreciated. A temporary member of staff was brought in to look after the telephones and all staff were asked to spend time thinking about the personality of the Society and how best to project that outside the organisation. All staff were asked to come along having thought about what kind of character the society had, and to illustrate this through the choice of a familiar character.

This produced some interesting answers. Jeeves was mentioned several times (very well connected, highly competent, but discreet and in the background), as was the coherent, articulate but essentially shy Clark Kent (rather than his alter ego, Superman). Many staff articulated frustration at the Society’s tendency to hide its light under a bushel. Later in the day, the words used to describe the organisation were similarly considered – in order to best convey the values and expertise of the organisation to an external audience. They spent time looking at colours and typefaces, and how these worked in a variety of different platforms.

Online communication manager Anna Ganley comments:

Brandguild then presented their feedback. They talked about their research into the role of the society, its audiences (actual and potential) and discussed how the organisational brand could best be expressed in personality, words and colours. Focusing on the strategic aims of the process prevented it from just being an exercise in everyone commenting on their favourite colours. There were reference points to build on; the long-established connection between blue ink and writing, and the printing colours that worked well with blue. We wanted to have different versions of the same brand for each of the society’s subgroups – and enjoyed thinking about sensible links. Blue and gold for awards information seemed particularly appropriate.

As a result of the creative day and wider research, three designs were presented to staff and discussed by the board of management. One emerged as the favourite early on, and once officially confirmed as the choice, Brandguild were given the go-ahead.

Ironically, the final stages took almost as long as the initial ones, when much bigger decisions had been made. There were serifs and decorative scrolls to play with, and Pantone lists to move up and down in search of the perfect combination. Some issues also emerged at the last minute (were they ‘The Society of Authors’ or ‘Society of Authors’?) but also at a late stage a very useful set of monograph ‘crops’ emerged, ideal for presentational use on certificates.

Nicola Solomon comments:

When it was ready we just started using it. Some have expressed surprise that we did not go for a formal launch of the new design. But we felt this process had been about us as an outward-facing organisation, and so having decided on how we wanted to present ourselves we should just get on and do so. Fundamentally the new brand is there to show we are fresher and better but does not signify a change of direction. And we have had only positive feedback. Right now it is being rolled out across all the information we send out, as materials are used up we reprint or represent with the new branding in place – and this has shown us once again just what a wealth of information we offer our members.

Was it all worth it? Resoundingly yes. The rebranding has been positively responded to by staff, members and those we seek to influence. Overall it represents a positive – and very busy – future for the society.

Figure 15.1 The Society of Authors’ old logo. Courtesy of the Society of Authors.

Figure 15.2 The Society of Authors’ new logo. Courtesy of the Society of Authors.

Marketing children’s books

Most general publishing houses have a children’s division and, although pioneering work was done (in particular by Kaye Webb, founder of Puffin, and Sebastian Walker, founder of Walker Books), until comparatively recently they were often seen as subsidiary activity to the development of the firm’s main list. Advances and royalties on children’s titles were based on lower-selling prices and so were worth less in cash terms to authors and illustrators. Children’s authors attending events got less for their appearance than those writing titles for adults. The books received smaller promotion budgets and shares of company attention.

Today the area is vastly more active, and this is happening worldwide. The quality of children’s books is better than ever and they are reaching the market through an increasing variety of outlets. Children are also buying books for themselves, often through school bookselling operations. Within the children’s market in general, it is notable that sales are robust and have been relatively stable for the past 10 years, holding their own in a market where sales of adult titles have been declining. There has also been a slower encroachment of digital media on the physical market here, with digital products accounting for around 11 per cent of sales in both the UK and US.

Opportunities for children’s publishers today

• Polarisation of the marketplace, with the emergence and dominance of key brands and authors in bestseller lists

In 2005, market research company Mintel reported: ‘The Harry Potter series has become something of a crossover, popular with both children and adults, as has The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time. This could perhaps mark the creation of a new genre of books, appealing to all ages.’5 ‘Crossover titles’ subsequently entered the publishing industry’s vocabulary and has led to separate editions of the same book being jacketed differently for various age groups. For example, books by J.K. Rowling and Philip Pullman, originally created for children, became media properties and were increasingly read by adults. This heralded the emergence of the young adult (YA) market, with authors such as Suzanne Collins and Stephenie Meyer becoming huge successes; as they became media-driven phenomena they were increasingly and enthusiastically read by adults, and now dominate in the bestseller lists. The specific vocabulary of these mass market titles has become part of popular culture – pub quizzes and crossword puzzles require you to know the meaning of ‘muggle’, ‘alethiometer’ and ‘vampire romance’ – and they consequently get read by all generations.

Other opportunities have emerged for big sales. Humorous titles aimed at younger markets such as The Diary of Wimpy Kid series and books by David Walliams were seized upon by schools and literacy champions as material that encouraged wider participation in reading and have become hugely popular. The rise of online gaming, and its spin-offs as book-related products (e.g., Minecraft), and the rise of character and brand licensing (often related to content that has nostalgia for parents, e.g., Lego and Star Wars) have proved very significant in this sector.

• New formats for children’s publishing

Children today are digital natives, born into a world where time online is part of their daily lives – and if they do not gain access at home, they learn to use computers at school. Through this, new opportunities for accessing and sharing content have emerged, and the dictionary definition of the term ‘passback’ has widened from its use on the football pitch to include the handing back of a mobile phone or tablet computer to children in the back of a car to keep them quiet. New computer formats (e.g., the tablet) have led to new delivery mechanisms for content sharing within children’s literature which are encouraging children to read and involve themselves in the stories they access. Many (but not all) of these opportunities are being developed by traditional publishers, with their understanding of content development and marketing, to home and international customers and agents. As Kate Wilson, founder of Nosy Crow6 (children’s books and apps) commented:

We make innovative, multimedia, highly interactive apps for tablets, smartphones and other touchscreen devices. These apps are not existing books squashed onto screens, but instead are specially created to take advantage of the devices to tell stories and provide information to children in new and engaging ways. We don’t want reading to be the most boring thing a child can do on a touchscreen.

We know it’s subjective, but Nosy Crow wants to be proud of everything that we publish and make. We want to be sure that it meets the need of a reader (or emerging reader), and meets that need as well as it possibly can. That means great illustration, great design, great audio, great video, great animation and really great writing. We go out of our way to find these things from new and established talents.

• New selling locations to reach the mass market

Supermarkets experimented (through Walker Books) with own-brand books in the 1980s, although the novelty of being able to buy children’s reading material where you bought other essentials was quickly overtaken as supermarkets turned to selling branded blockbuster titles as ‘loss leaders’ to draw shoppers in store. But the ongoing needs of the gifting market, which remains consistently buoyant for products for children, have promoted an expansion of other places to buy and helped lift children’s books to be rated alongside toys and computer games as a first-class profit opportunity.

Today most large centres of population are ringed by out-of-town supermarkets and superstores where people with small children are likely to shop and, crucially, find it more convenient to buy books. As well as selling books through supermarkets, books also sell well through superstores selling child-related merchandise, and can benefit from being displayed alongside non-book child-related products such as toys and prams. Through these outlets, books are being sold to a much wider group of people, as many of the customers are probably not regular bookshop browsers. Purchases are often made on impulse, and there is huge demand for high-profile media-related properties of the kind publishers can offer, with a price offer or associated discount being a key part of the consumer expectation.

Leisure and food venues are another key opportunity for publishers to work in partnership with organisations who are approaching compatible audiences but with non-competing products. Partnerships are beneficial both ways: publishers reach many non-regular book-buyers, but the merchandise they make available may confer brand benefits on the host organisation. Major publishing houses spend a lot of time trying to establish and maintain such sharing, for example with books being included in branded children’s meals and as part of the customer value proposition for ‘day out’ venues.

Another new arena is the sampling of books through non-retail outlets, and in particular the workplace selling of books, which has expanded dramatically in recent years. Firms involved in this (notably The Book People7 in the UK) buy large quantities of a limited range of stock, display the products in staff space and collect orders at the end of the week. Children’s titles can work very well here; backlist titles can drive subsequent demand for the front list, in particular with nostalgia titles that are familiar to parents. Similarly books on sport for boys, reference titles linked to the school curriculum and reading packs that offer value for money are all popular. Retailers can demand huge discounts but they are reaching customers who do not frequent bookshops (and hence are expanding the market), they buy firm (no stock gets returned) and their orders can often make a print project financially viable.

Packaging is vital for these locations. Books often become more attractive when marketed in combination with toys and clothing, as a branded item appealing to a child with specific interests. Packaging that adds value to the product is particularly important: for example in warehouse clubs, catalogues and cash and carries, shoppers tend to be looking for a higher price and bulkier looking purchase (this is particularly important if the item is to be given as a present, as customers appreciate a large box to wrap). For some outlets the publisher may produce own-brand items; packages that consist of ‘books plus’ may become part of the store’s gift or hobby range rather than book range. What is more because they are aimed at gifters rather than book-buyers, they target new audiences – and hence may be stocked in greater depth, particularly during peak times in the seasonal gifting market.

The traditional book trade has reacted in varied ways. In general the children’s department is easier to find than it used to be, and children’s titles are now part of the major promotions at the front of the store. Some major bookselling chains have experimented with dedicated children’s shops, but the combination of excessive rents for high street sites and low-price products is a difficult one, and many casualties have occurred. Even shops that were once thriving concerns, functioning as centres of advice and encouragement on reading, with welcoming premises and detailed knowledge of their stock are now threatened, and the closure of the Lion and Unicorn Bookshop in south London in 2013 – the first children’s store ever to win the prestigious title of Independent Bookseller of the Year – was dispiriting. As head of membership services at the BA Meryl Halls commented, this would ‘leave a huge hole in the specialist children’s bookselling sector, and in the visibility of children’s books on the high street, and in schools’. Halls added: ‘The closure highlights the torrid pressures on high-street booksellers, and retailers generally – a massive rent increase can put a once-thriving business over the edge of viability, and taken together with business-rate pressure, the combination can all too often be fatal.’ She also called on local and national government to ‘look at the health of our high streets with increasing seriousness if we are not to see a continuing diminution in the vitality, diversity and creativity on our high streets – bookshops being a key indicator of the health of our local retail communities’.

Other retailers have nurtured special markets. The organisation of school book fairs and school book clubs is an area of strong competition and activity. There is some special publishing for this market, in the form of book and activity kits. But with growing market assumptions about buying online being a norm, and consumers often using bookshops as showrooms where they examine what they will later purchase from home, it can be very difficult to compete.

• Character licensing arrangements

With the wide availability of films for children, online and via networks, and the marketing efforts of the Disney Corporation, there has been considerable growth in demand for ‘character’ images created for a book or film to adorn a wide variety of specially designed merchandise – from nightdresses and bedroom slippers to rucksacks and school lunchboxes. With their backlist of character titles, publishers are well placed to take advantage of this opportunity.

Superstore purchasers shop thematically, following the child’s interests; they may not be looking for anything as specific as a book or cutlery set, but a Pooh Bear or Thomas the Tank Engine item and books can benefit enormously from the creation of ‘retail theatre’ through cross-merchandising, displaying books in an accessible position alongside related merchandise. Event publishing and seasonal opportunities are of increasing importance, tying in with periods of raised consumer footfall such as Mothers’ Day, Christmas and other key gifting periods. Some stores take this a stage further by launching specific boutiques within stores for certain characters that have a strong affinity with their own market.

• Educational upheaval and parental anxiety

Changes in the educational environment have created an opportunity for children’s publishers, in both new resources for schools and to support parental anxiety. For example, there is now a considerable market for resources to practise for tests and assessments as well as resources for reading and project-based homework. There are also opportunities for publishers arising from events and anniversaries, e.g., World War One, the Olympics, happenings within the Royal Family and annual events such as the birthday of Martin Luther King or Shakespeare. Major publishing houses employ reps to call on schools and sell both educational and reading resources, usually basing rewards on commission.

• Opportunities to meet authors

Book events, festivals and other opportunities to meet authors through special appearances are of growing importance for book-buying. The rise in literary festivals has been a notable trend worldwide, and each of them now generally has its own associated children’s programme that often holds some of the most highly attended events – and at which huge numbers of titles can be sold. British author Jacqueline Wilson holds the record for the longest book signing – more than 8 hours (incidentally without a comfort break). Children want to meet their favourite authors, and these opportunities have become hugely profitable.

In some instances, where children’s books are the product of team writing, a range of different authors may be despatched to talk on behalf of the writing team. Along similar lines, for non-technical authors – or those disinclined to participate in marketing – it may be the publisher who maintains a website, updates it with new information and replies to letters from children.

In addition to live events, there are opportunities to connect through social media and to live stream author events in real time. Authors can therefore connect with fans without going on time-consuming or costly tours, and digital assets of author events are created in the process.

• The long tail for children’s titles

The marketing manager for a children’s list will also spend a good deal of time and money promoting the backlist, not just new highlights. Whereas a new general hardback fiction title will have its heaviest sales period in the months following publication, with another boost when a paperback or ebook appears, children’s titles can take a much longer time to get established – and then go on selling for much longer than adult titles. Where titles last between generations, there can also be a significant nostalgia market, with parents buying books by authors they enjoyed, or about similar subjects – some of which never go out of date, but may be presented in new combinations (e.g., fairy stories, tractors, dinosaurs, teddy bears).

Key difficulties for those marketing children’s titles

• Marketing is often through intermediaries

While school book fairs and book tokens and vouchers offer the chance for children to choose first-hand, there is a key difficulty for children’s publishers in that the marketer often has to convince a middle market. Booksellers and wholesalers have to be persuaded to stock titles, and parents, relatives, teachers and librarians to buy on behalf of the children they represent. Even those promotions that are sent straight to children (e.g., school book club leaflets) rely on teachers to organise and parents to pay. A high percentage of book purchases are paid for by adults; parents but also ‘graunties’ (grandparents/aunts and uncles/closely involved adults). In demographic terms, the spread of adults buying for children is very wide, making the targeting of marketing very difficult. For example, many titles are bought by adults who are not responsible for children or by much older generations, and their preferences have to be borne in mind.

Each year publishers produce catalogues and leaflets detailing their new and existing titles. In addition they prepare a range of promotional material for display in shops, schools and libraries: posters, leaflets, balloons and so on. This must be attractive both to the adult (so it gets put up) and to the children who will see it. Appealing to ‘the child in us all’ is not as easy as it sounds. Children today are sophisticated and acutely conscious of being patronised. They can be persuaded that a book is not for them by a quick glance at the cover (particularly important when they are doing the buying through an online bookshop and that is all they see).

Children’s language also changes all the time, and while they will not expect to see the current hot terminology on the back of book covers, they can be very disparaging about words that sound out of date, and hence inclined to damn the product through association. Publishers do not need to talk like teenagers (they could not do it anyway) but they do need to have a sixth sense to spot terms that will date.

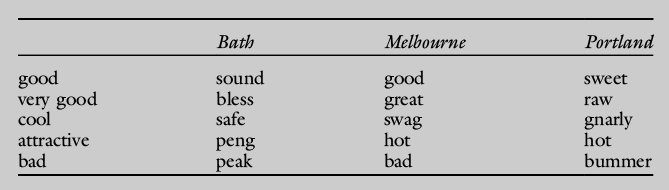

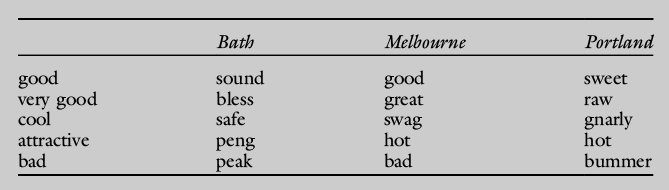

Just to illustrate this, here are the current terms used by three 14-year-old boys in specific locations in Bath (UK), Melbourne (Australia) and Portland, Oregon (US). I say specific locations, because 10 miles down the road they would probably be different.

This illustration is not designed to pass comment on their vocabulary, but to illustrate how rich, temporary and localised it is.

• Children’s publishing is probably the most price-sensitive area of the book trade

Economies of scale are vital where high development costs on mass market novelty formats necessitate high print runs and hence volume deals. Mostly this is done using a schedule of discounts, rising according to the quantity bought. At the same time, costs must be kept as low as possible, and most authors are remunerated on the basis of net receipts rather than published price.

Children’s books are highly price-responsive. There is a symbiotic relationship between retail price and volume in the mass market; adding an extra 10 per cent to a title can ruin its chances of success. Shoppers in out-of-town superstores are particularly price-sensitive. People are often looking to spend a specific amount of money, and given that there is so much choice, will allow the pre-set budget to be the main criterion for decision-making. When pricing new materials publishers need to benchmark their prices not only against competing books but also against non-book products (e.g., toys, stationery and gift items) that jostle for the same leisure spend. Money off can be a significant marketing gambit at certain times of year (e.g., Christmas), but in general low retail prices mean there is less margin to play with.

Finally, children themselves are very price-conscious. Youth today has more disposable income – working parents who are not at home tend to compensate with bigger allowances – but with this has come an increased consumer confidence. They are used to shopping around and an awareness that books in particular can always be found somewhere cheaper was ironically fostered while they were still at school, by teachers encouraging them to read. For many UK children, their first experience of market economics was at primary school when they learned that the new Harry Potter was available and that it was cheapest at a particular supermarket.

Marketing techniques for promoting children’s titles

The new selling locations have necessitated a switch in marketing techniques. Instead of concentrating their energies on pursuing every possible opportunity for free coverage (how children’s books used to be marketed), publishers have had to become increasingly aggressive to maintain these opportunities, which are under threat from both adult books and a variety of other merchandise with potentially higher stock turns and profits.

Attractive printed material is still a mainstay of children’s marketing: something that will make an impression on the book-buyer and provide a taste of the quality of the product. Posters and other free material for schools and libraries may directly impress an author brand on pupils with long-lasting consequences. For other markets where value for money is important, cheaply produced materials give a quick impression that there is plenty of choice, limited price special offers, or deals so that purchases above a certain price attract free carriage, can all encourage a quick response.

The creation of interesting websites where children can find out more about their favourite characters is also very important. Children feel a character or title is more real if they can access information online to back it up. Such websites need to be sophisticated, interactive and regularly updated – publishers are marketing here to the most net-savvy generation. Similarly, non-fiction titles that offer checked web links can be welcomed by parents. Books have been through extensive processes of checking and so are more reliable than the web, but ‘listing 1,000 checked websites’ on the front of a reference title makes it look more appealing and up to date to the children they are buying for, and is reassuring and time-saving for parents (they don’t have to check the sites themselves).

Generating free publicity

Children’s publishers often complain of the paucity of review space devoted to their books, although blockbusters such as Harry Potter have broken the mould, with reviews commissioned from children who stayed up all night reading the new book appearing on the news pages (the experience handily enhancing their CVs at the same time). However hotly editors protest their independence from advertising, it is true that children’s publishers in general spend little on space in anything other than trade magazines, and that is usually concentrated in the run-up to relevant book fairs. But as the area becomes more profitable, and they advertise more, there will be more editorial features on children’s books.

Opportunities for free coverage may include:

• Social media. Children are not officially allowed to be on Facebook until they are 13 or Twitter if they are under 10, and data protection and online security issues impact on signing up for online fan sites without parental approval, but social media can certainly be used to reach their parents. The blogosphere is particularly important in creating pre-launch buzz and social media can offer opportunities for giveaways, samplers, exclusive content, allowing authors to connect with the fan base in a direct way. Mentions on sites frequented by the parents, blogs and tweets can all drive traffic to relevant websites for more information, or ordering mechanisms for those who decide they want instant gratification.

Social media platforms cross international boundaries, and it is helpful to benefit from access to global digital content. The noise created around new products when launched in other markets can be helpful, as can an attempt to ensure consistency in packaging across markets in order to benefit; sharing digital assets such as authors interviews and book trailers. For ideas on how to work with a blogger, see Chapter 9.

• Organising promotional links with websites, magazines and newspapers read by parents and children, for example, features that ‘review’ new titles, articles on key authors, and sponsoring competitions which feature the book as prize and hence promote word-of-mouth. Magazines aimed at children are often particularly keen on featuring extracts from forthcoming titles that appeal to their core audience.

• Producing free branded material for information carriers such as posters, bookmarks, balloons, height charts, party packs, ‘make and do’ samplers. All of these offer longevity and thus may go on promoting the associated titles long after distribution.

• Arranging author tours, usually to a specific region for three to four days at a time: handling bookings from schools and libraries; liaising with the local press; arranging for copies of the relevant books for signing sessions.

• Organising the firm’s material for national and international book trade events and working with agencies involved with inclusion and the promotion of literacy. In the UK, events such as National Children’s Book Week,8 World Book Day9 and the Reading Agency’s Summer Reading Challenge10 encourage reading stamina, and generally operate through a combination of online activity and an accompanying press campaign to raise awareness and the despatch of physical materials to encourage the organisation of reading-related events in schools and libraries. Along similar lines, working with agencies such as the National Literacy Trust,11 Reading is Fundamental12 and other inclusion organisations that promote literacy.

• Supporting specific local initiatives: perhaps supplying local booksellers with marketing material for a promotion they have organised or arranging for a character in costume to pay a special visit to a school.

• Sponsorship of events relevant to the market. It’s common for primary schools to have dressing up days, and book-based themes are popular (e.g., come as your favourite character).

• Entry of titles for literary prizes. The resulting media coverage brings the winning titles to the attention of a wider public, as well as promoting reading and books in general.

Book fairs, exhibitions and conferences

At book fairs the major trade players gather for the sale of rights and to display their wares. The trade press lists attendees, and this provides a useful summary of the main houses involved in children’s books. Notable events include the Bologna Book Fair and the Shanghai Children’s Book Fair. Other international book fairs around the world have specific exhibition space for children’s publishers, and many publishers have an exhibitions team that can be despatched to mount displays at teachers’ and librarians’ conferences, teachers’ centres, schools, local fairs and other events. Local sensitivities and laws will have to be borne in mind when deciding which titles to present, and which may need rewriting for local markets (e.g., alcohol is available to 18-year-olds in the UK; in the US the age limit is 21).

Exporting children’s books

Gaining an export deal for a children’s title, or series of titles, is often the way to make the process profitable, and if material can be translated and exported, there is the opportunity to raise valuable revenue from co-editions, rights and royalties. A series of co-edition deals, secured at the right time, can be the key to successful publishing of a children’s title, allowing the publisher to extend the initial distribution and keep the price down. The more expensive the format, the more important this becomes, so it’s especially vital in colour books. Some publishing houses have set up arrangements with indigenous publishing organisations in their formerly traditional markets, to buy export editions or co-publish for the home market bearing in mind particular market sensitivities and catering for distinct market tastes and trends. For more information on exporting, see Chapter 7.

Selling resources to public libraries

The words ‘and libraries’ often appear on the marketing plans for new titles, but it is worth thinking about why libraries should be a key part of all marketing planning. In the past publishers have known relatively little about the public library world; there are very few job moves between the two professions, and publishers have tended to take library sales for granted. It’s also worth understanding the role of the public librarian, which is far wider than just lending books.

Librarians offer the markets they serve access to content in a variety of different formats and delivery methods. But their prime function is access, not recommendation; their loyalty is to the markets they serve, not to any particular format or publishing house. While the vast majority of the stock they buy is still focused on popular leisure reading, increasingly they are interested in stock that supports the wider needs of their communities. For example they buy stock to support public health initiatives, basic literacy, job hunting and up-skilling, community development, equalities and non-English speakers. They also work with broadcasting campaigns and charitable partners such as the Reading Agency and the Royal National Institute for the Blind to reach new audiences, and work in partnership with publishers to raise awareness of key titles.

Sue Jones, former Hertfordshire librarian and now working for the Reading Agency comments:

Library support for the huge rise of reading groups in the UK is a good example of how libraries support community initiatives. Local groups will probably support local authors, and although libraries may be unable to buy stock on spec, local advocacy may lead to creating a demand that they will try to meet. I think requests from reading groups are increasingly driving purchases – libraries frequently get multiple sets of new choices if they think that other groups will be interested. Hertfordshire Libraries lists what other groups are reading on their website and in their e-newsletters. Libraries also regularly run their own mini reading festivals and collaborate in organising local writing competitions. So authors who would like to promote to a local audience are well advised to request an opportunity to speak.

Librarians will tell you their regular users are skewed towards those who are at home for at least part of the day: the retired, the unemployed and mothers with small children. However, some very interesting groups are spending more time in libraries. In the United Kingdom, the National Centre for Research in Children’s Literature has revealed that children from ethnic minorities, and in particular girls, make much more use of local and school libraries and there are new community initiatives to keep libraries open, or open new resources, through volunteering and book donations.13

Rather than just seeking leisure reading, today many of their customers are using libraries in new ways: local businesses as a wide-ranging resource for market information, job seekers who access the internet for job vacancies and updating their CVs, local and family historians for the specialist services available. Libraries also play a significant role in countering the digital divide by helping people to get online. All these activities result in active use of the library’s resources but record no corresponding loans.

In the UK, adult loans are down but children’s borrowing is rising. The decline in adult loans may be for various reasons. The reduction in library opening hours, cuts in the book purchasing funds and reorganisations of how the money is both allocated and administered can impact on the attractiveness of the stock available – and readers lose interest if fewer titles by their favourite authors appear on the shelves and the stock starts to look worn. Purchasing budgets for libraries increasingly have to cover information access through methods other than title purchase, and the costs of libraries offering technology and entertainment through internet access, audio and downloads all depletes the book purchasing funds. It is also significant that opportunities to purchase publishers’ output have expanded, both online and through accessible prime retail sites (supermarkets, garage forecourts, garden centres and so on), and this has arguably increased the public’s willingness to buy rather than borrow – and do something else rather than read.

How to send information to public libraries

Public library purchasing has undergone a radical change in recent years, moving away from the former model, which enabled individual library authorities to select and purchase their stock from their choice of supplier. Libraries are now locked into consortium arrangements whereby the library authorities to which they belong provide detailed demographic profiles of the areas they cover and these are matched by centralised library suppliers, with publishers pitching to get their titles included in the selections that are presented to libraries. This is partly due to reduced budgets, but also to central governmental plans for the cost-efficiency of national purchasing models (which cut down on administrative costs, increase the size of the resulting orders and ensure best prices – and hence value for money).

What librarians decide to stock is based on the information they receive and their wider understanding of what is available. Organisations that sell resources to libraries edit the range available and offer a selection, and most librarians rely heavily on this filtering service. As one commented:

We generally treat unsolicited approaches badly – partly because there’s a wealth of poor-quality material out there and partly because of lack of time. We prefer to get approaches through our aggregators first, and from the purchasing consortia or from other trusted agencies.

This is supplemented by their own awareness of the wider range of material available, but lack of time means this is usually a personal commitment rather than a job requirement.

Librarians read the professional and trade press to gain information on what is being launched; they also respond to their users’ requests for specific resources. They acquire information on what their regulars want to read or use through experience and constant handling, checking and updating of the stock, but they also have local agendas to meet, such as widening access and outcomes for learning and skills, health and well-being and community cohesion. Most librarians retain a particular interest in searching for, and purchasing, locally available material likely to be of interest to the increasing numbers of people researching their family history.

When targeting librarians via their purchasing consortia, through their official publications and via forums they access, bear in mind that the profession is highly collaborative, in that decisions on what to buy are taken in consultation with colleagues. But it’s vital to note that while decisions are discussed, most of the subsequent buying is done online. Thus while librarians may look at a synopsis and the cover, they don’t get the chance to read a few paragraphs, or to handle a publication, before deciding whether or not it should be stocked. The information publishers provide is thus vital in creating the right kind of buying information for each title, and organisational reputation as a firm that maintains standards of a particular kind (whether good or bad) will support the decision-making. Memories of failed promises can live a very long time.

Information to emphasise to librarians

Librarians are information management experts so it is vital to ensure that information sent to them is well managed: fully navigable, logically presented and accurate, backed up by the appropriate bibliographical details. Other information that may be particularly relevant to the library market includes:

• Which courses or educational stages your title is relevant to: in particular, if your products relate to project or course work for specific educational stages. For example, local children’s libraries in one area are well stocked with reference books on Spain for 10- to 11-year-olds because a local head teacher sets a project on the country for the final year of junior school.

• Any significant overlaps between subject areas. This may enable them to pull money from several allocations. The wider the spread of interest groups they serve, and that you meet, the more likely your resources are to be purchased. Cross-curricular, interdisciplinary areas are particularly attractive.

• Feedback from readers. If titles have attracted demonstrable evidence of popularity, perhaps through online sampling or reader feedback, this could be important evidence to offer.

• Author availability. Authors who do events in public libraries, and support the ethos of free availability of reading matter within the communities, fit the library ethic and are an asset to librarians.

• Products that offer librarians the chance to enhance the prestige of their collection. Librarians identify with the collection they look after and products that enrich the collection as a whole, and enhance the resources available to their users, are attractive.

• Librarians often have to order at the last minute or risk losing their budget for the year ahead, so information that might make them choose your content in a hurry is valuable. An appropriate high-price product takes less time to order and enhances the range of resources available to the reader in one go.

• Production details. Librarians are looking for resources that will last and are consequently keen to hear about appropriate product specifications – search engine usability, acid-free paper, sewn rather than glued bindings and so on.

• Good covers matter enormously. Librarians play an important role in tempting people to read and titles are often displayed face out, rather than spine on.

Case study

How libraries and publishers can work together to greater effect: an interview with Helen Leech, virtual library services manager, Surrey County Library Services

In a climate of financial cutbacks in public spending, with the value of libraries and their usefulness being questioned and many librarians facing budgetary cuts or closure, the response from librarians has been robust. Many have established new initiatives to promote awareness and cooperation, to expand and change working practices, to reach out to the wider public and stress the value they offer.

There are now many libraries run by volunteers. The model tends to be that of ‘Community Partnered Libraries’ where the council provides the resources (including the premises and their upkeep) but the local community provide the staffing. Other solutions include ‘Community Links’, which generally means making collections of books available in village halls and other premises, the community providing all resources and staffing and the library service providing the books.

We are becoming more community-focused, meaning a number of things: we’re moving away from being a take-it-or-leave-it service with minimal engagement, and we’re broadening our range of services and actively working with community groups. For example, Surrey Library Service runs a support service for domestic abuse survivors, for which we won an award, and just this morning one of our staff sent me a list of the things we do and the partners we work with for each ‘protected characteristic’ within the Equalities Act, and it’s remarkable. We are moving from supporting leisure reading, which is certainly a declining market, towards services supporting local agendas, working with a range of local partners.

As to how libraries and publishers can work together in future:

The key message from the Society of Chief Librarians is that public libraries are keen to work with publishers. We’re part of the same ecosystem; we have the same passion for books and reading, the same desire to lead the reader to the right work, a lot of the same issues in terms of the challenges of a hugely changing market. It would be to the benefit of both sides to work more closely: libraries can offer access to a very large market; publishers can offer experience and content.

In terms of what we bring to the relationship, publishers are interested in our huge audience. Even though loans are falling, the number of those using the libraries is still huge. In Surrey one person in six (200,000 people out of a population of 1.1 million) has used the library in the past year. In addition to those who use the library premises, we have a large community outreach through our newsletters and online services.

Libraries offer a huge showroom window for publishers’ works and given that a large part of our remit is reader development,14 this too offers big opportunities for publishers. At a time when high street bookshops are closing, we’re introducing readers to new authors and encouraging people to broaden their reading habits. These days we are also much more involved in promoting titles to our readership than we used to be, and very aware of the power of the cover to attract. Like booksellers, we now put a lot of our stock face-on and expect the book to sell itself. There are also simpler book recommendation schemes operating within libraries such as the recommendations of our very knowledgeable staff, our ‘just returned’ trolley (which is where many of our visitors head first on reaching the library) and the book recommendation schemes we run, which encourage people to move outside their reading comfort zones.

Many reading and some writing groups are also run under the auspices of libraries. Within Surrey alone we support more than 700 such groups in a variety of ways: drawing up and circulating lists of suggested titles; providing loan stock of multiple copies of the same book; promoting and hosting some of the groups within libraries. We also send out a regular newsletter to 120,000 readers in the area. There are associated opportunities for publishers to gain ‘focus group’ feedback on jacket design and format, and for the test marketing of new materials, subject areas and authors.

We are very interested in the communication possibilities around books as a way of extending involvement. For example the Reading Agency’s Digital Skills programme has been encouraging libraries and publishers to work together and one of the things we’ve found really helpful is the promotional materials that publishers can provide – not just the traditional posters-and-bookmarks, but now the online reviews, ratings, recommendations, graphics, ‘who-else-writes-like’ forums, blogs, and other things that help us to generate interest and discussion. We take a much more retail-, business-like approach to books these days and, like every other part of the book trade, we’re far more likely to promote a particular author when we’ve got the materials and it’s quick and easy.

We also offer market data on reading patterns. Although this is in its infancy, it is an area of growing interest and one that could be capable of growth to enable more precise targeting of information. Speaking on behalf of Surrey, we collect information on library-user postcodes and age, but this has significant opportunities for development. Potentially we could identify pockets of gardeners in Lingfield and Chinese people in Woking and we could possibly tell you what they are reading. Demographic analysis is an area we need to develop, bearing in mind data protection restrictions, but there’s a huge opportunity to work with and learn from publishers.

Public lending right

Most territories now have some form of recompense payment to authors for loans of print books (and there is hot discussion over the inclusion of ebooks). The principle of the legislation is simple. Authors earn their living through the royalties on books sold; those sold to libraries may have many readers but only produce one sale and royalty payment; the schemes act as compensation for these ‘lost’ royalties. The funding comes from the public purse and arrangements for distribution vary from country to country.

Such schemes have revealed interesting borrowing patterns, which do not always tie in with sales patterns through bookshops – and perhaps there are titles it is logical to borrow rather than buy. The feedback provided is used extensively in public libraries. This includes subject breakdowns, lists of ‘classic’ authors and comparisons of local, regional and national trends.

Finally, don’t forget that in the same way that public library services are working with local community volunteers to ensure continued access to reading material, there are also library facilities that originate within the wider community that meet similar needs. Book-rich environments are often seen as relaxation zones that enhance community living, and each one offers the chance to promote reading and publishers’ wares.

Case study

Betty’s Reading Room, Orkney, Scotland15

Craig Mollison and Jane Spiers, a couple now living on Orkney, created a library there in memory of Betty Prictor, a close friend and book lover who died unexpectedly. Craig, Jane and Betty were at university together in London, all went into teaching and had regularly spent holidays on Orkney, all planning to live there in the longer term. When Betty died before this could be achieved, Craig and Jane were keen to create a positive memorial that would also benefit the community as a whole. As Betty was an avid reader, they hit on the idea of a reading room in her memory – and her books are now part of the collection that is named after her.

The starting point was the shell of a derelict bothy16 in Tingwall, donated by a local farmer. This they refurbished and decorated, with help from the local community, to create an attractive environment for relaxation and reading. The building is heated by a wood-burning stove, lit by gas lamps and it is kept open at all times. Craig or Jane pop in at least once a day, not least to light the stove in winter, but otherwise it operates entirely on trust. The visitors’ book shows that it has become a popular dropping in place – one wrote that the experience of stepping inside ‘gladdens the heart’. It’s also become a haven for those waiting for the boat from the Orkney mainland off to the isles, who would otherwise have to wait outside in their cars in the cold and dark – and is now also firmly on the Orkney tourist trail.

The stock comes from their own books and those of Betty, donations, gifts and swaps – readers are welcome to take a book and leave one of their own in its place. They provide attractive bookplates that can be stuck into the front of titles that are taken, and ask that once finished, they are passed on to other readers. Craig and Jane appreciate the random nature of book discovery and so the books are placed on the shelves in a serendipitous order. One librarian used the visitors’ book to comment that she found this frustrating – she longed to submit them to the Dewey classification. The only titles they keep to one side are children’s books, which they place in a separate corner.

The room is used by several book groups and reading circles and has also been used in poetry festivals, The Orkney Story Festival and for musical evenings. It’s now a valuable community resource, firmly on the tourist trail – and word seems to be spreading. Craig and Jane are sure that Betty would be absolutely delighted.

Promoting to university academics

There have been huge changes within universities in recent years. If you are tasked with promoting to this market, it is important that you understand what has happened.

A huge increase in student numbers

There is a worldwide move towards mass education at higher level (its ‘massification’). Targets are various, but based on evidence of university attendance as a long-term investment in an individual’s future, the intention is to have a much higher proportion of the population which has benefitted from a university education.

Changes to funding models

The vastly increased numbers mean that older funding mechanisms have had to change. Various models for this have emerged. In some countries, large numbers of students are subsidised through commensurate rises in taxes, although governmental funding often leads to tighter control of student numbers and fierce competition for places. In other countries, students are forced to pay either a proportion or the full cost of their education (its ‘marketisation’).

Governments that rely on those benefitting from a higher education to pay for the privilege can generally accept more students, and there is thus a wider market for potential publisher resources, but this tends to be accompanied by less time for reading and less money available for book-buying. In general, funding works through a system of student loans, which recipients start repaying once their post-graduation income reaches a particular level. But this means that many students are holding down part-time (or even full-time) jobs to pay the fees, and there is consequently little money around for buying resources.

Paying for learning has arguably always prompted an assumption that with the contract comes some transfer of responsibility. As schoolmaster Bartle Massey commented in Adam Bede:17

You think knowledge is to be got cheap – you’ll come and pay Bartle Massey sixpence a week, and he’ll make you clever at figures without your taking any trouble. But knowledge isn’t to be got with paying sixpence, let me tell you ... So never come to me again, if you can’t show that you’ve been working with your own heads, instead of thinking that you can pay for mine to work for you.

There are signs today that with the changed responsibility for funding higher education has come a changed attitude of students. They are tempted to see themselves as consumers of – rather than participants in – the learning on offer. Naomi Klein (2000) commented in No Logo:

Many professors speak of the slow encroachment of the mall mentality, arguing that the more campuses act and look like malls, the more students behave like consumers. They tell stories of students filling out their course-evaluation forms with all the smug self-righteousness of a tourist responding to a customer-satisfaction form at a large hotel chain … students slip into class slurping grande lattes, chat in the back and slip out. They’re cruising, shopping, disengaged.

Academics who mark their work regularly report that students subsequently lobby for an increase in the percentage awarded, significantly not on the grounds that a specific piece of work deserves a higher mark, but that their overall average requires it. The new ubiquity of access to information online has also been accompanied by a blurring of awareness as to whom it belongs, and the technology that permits access also enables the precise monitoring of its use – universities now generally require the online submission of work and its automatic assessment for originality. Plagiarism can be spotted and the penalties for this and other forms of academic misconduct (cheating in exams, getting other people to write your work for you) are severe.

Sometimes casual student behaviour conflicts with wider marketing forces. While for the lecturer it’s irritating to find students texting while in class, if they are instead live tweeting – which has the potential to spread enthusiasm for courses and draw in new students – then attitudes may differ.

A changed model of how education is delivered

The increase in student numbers has not, in general, been matched by a commensurate increase in staffing or facility improvements, and overall the character of the teaching experience has changed. Everyone is short of time. The pressure on academics to research and publish as well as teach has increased significantly. Some of the burden of classes has been moved on to research assistants, PhD students and part-time lecturers. Students are taught in larger classes and seminars, there is more use of group assignments (promoting collaboration and the development of presentation skills but also requiring less individual marking) and there has been a marked reduction in the former closeness of academic–student relationships. Some would argue that this motivates students to become independent learners, others that higher education is fast becoming a process of transferring information.

In general, publishers have been reluctant to give up the textbook model, which has long yielded profits and that parents (who understand from their own time in education that books support learning) have often been willing to underwrite (sometimes through online access to their own book purchasing mechanisms). Rich profits have been made by publishers offering the single textbook that supports a popular course. But the textbook model is now being reviewed for the online generation. Students are becoming increasingly unwilling to buy print editions when they become out of date so quickly. In some disciplines new editions appear annually, with few changes apparent, but an insistence that the new edition be purchased.

There is increasing demand for publishers to deliver content rather than a single format, with the availability of additional supporting materials (e.g., website and downloads) playing a key part in deciding which resources to adopt – even if they subsequently get little used.18 A publishing house is much more likely to sell content if it can make the bibliographic details and print-on-demand facility available, quickly and in standard electronic formats. Some publishers are developing standard ‘content cartridge’ models so that core content to support students can be loaded into the online learning tools used in universities.

Information managers are working with academic staff to build electronic profiles based on their interests, and they want to work with publishers and other suppliers to access information about new titles through these profiling processes. Instead of course reading lists, which students lack the time or inclination to consult, course administrators may now put together course packs that pick and choose from the various materials available, and provide all the supporting material in one handy source. But the huge class sizes mean that libraries cannot possibly hold enough copies of supporting resources in print form, and hence they are looking to publishers to provide them with ‘granular access’: e-content licensing opportunities so they can secure the bits they want, much as happens with online journals and databases. All are becoming intolerant of time-wasting in the ordering process.

The pressure to gain access to the resources they need will only grow, and information managers are meanwhile dealing with students and staff who demand instant gratification for the resources they need to support learning. All expect Amazon-style delivery, and electronic access wherever possible. Significant too is the internationalisation of higher education. Most universities have an international presence and these students, who pay higher fees, want electronic access to learning resources, not to know that there are ten copies in the library, wherever that is. Senior information adviser, business19 Margaret French comments:

Undergraduates tend to expect both print copies and ebooks to be available. The increasing availability of ebooks is not the solution we thought it would be. This is because the pricing of popular (i.e., core) ebooks can be extortionate. For example, 100 accesses to an ebook can cost up to triple the price of a print copy and with large numbers of students on some modules, 100 accesses does not last very long.

A change in the role of the academic