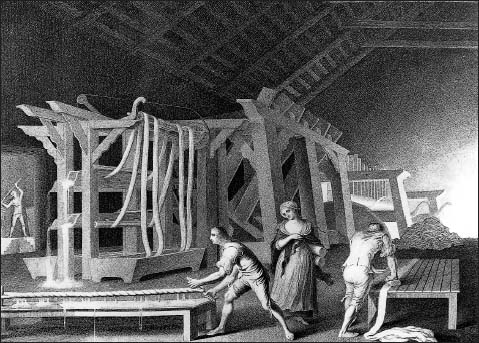

PLATE 9

A complete Perspective View of all the machinery of a Bleach Mill, upon the Newest and Most approved Constructions, Consisting of the Wash Mill, Rubbing Boards moved by a Crank, and Beetling Engine for Glazing the Cloth, with a View of the Boiling House …

WILLIAM HINCKS 1783

OVER THE 17TH AND 18TH CENTURIES in Ireland the preparation and spinning of both woollen and linen yarns by women in their own homes provided a major source of employment and income for many families. Women processed raw materials not only for the weaving of clothes and household furnishings for the Irish market but also for profitable export as yarn to thriving English textile manufacturing regions. Just as English wool had been exported to Flanders in great quantities by the twelfth and thirteenth centuries to supply the thriving textile industry there,2 so Irish linen and woollen yarns were being exported to several regions of England by the sixteenth century.3 By the end of the seventeenth century exports of wool and woollen yarns accounted for more than half the value of Irish exports to England and linen yarn for one-eighth. Because England could not produce sufficient yarns to service its own textile industries it had to pay good prices to attract yarns from Ireland. Although wool declined to less than 20 per cent by the mid-1720s it was replaced as a money earner by linen: whereas exports of linen yarn as a percentage of total exports peaked with worsted yarn before 1720, linen cloth provided two-thirds of the value of Irish exports as late as 1788.4 In spite of this export trade Ireland was still able to clothe its people, although it has to be admitted that most of the finer quality cloths were imported from England and the Continent. By the close of the eighteenth century, too, Ireland was producing at least one-third of all linens woven in the British Isles.

Although the woollen and linen trades in Ireland were both very important for Irish society and the economy, they developed in very different ways. The old nationalist tradition that the woollen industry suffered because the linen industry was promoted about 1700 by the London and Dublin governments at its expense, has been disproved. In general the home market continued to be dominated by Irish woollen cloth whereas the bulk of Irish linen was sold in the much more competitive English market along with large quantities of Irish linen and woollen yarns. Towards the close of the eighteenth century, however, as the home market came under heavier pressure from English industrialists, the Irish woollen industry was severely affected and hand-spun yarns became a thing of the past while the linen industry only survived by itself industrialising.5

In Ireland, as elsewhere, the domestic woollen industry had readily adapted to a ‘putting out’ system because it was possible for middlemen to buy up the raw material and prepare it for wage or piece-workers. By contrast the structure of the linen trade in Ireland made it difficult for middlemen to secure and exercise similar domination. The basis of this structure was confirmed by a clause in an act of 1719 (6 Geo. I, c. 7) that declared:

All linen-cloth and yarn shall be sold publicly in open markets or at lawful fairs, on the days such markets or fairs ought to be held, or within two days next preceding such fair-day; and all linen yarn shall be sold publicly at such markets or fairs without doors, between eight in the morning and eight in the evening; and if any person shall sell or expose to sale any such cloth or yarn except as aforesaid, all such cloth and yarn shall be forfeited.

Although this clause would have enabled middlemen to buy up flax for spinning into yarn, or yarn for weaving into linen, it acted as a strong encouragement both for those families who grew flax to convert it into yarn for sale in the public market, and for weavers to grow their own flax or purchase it in the yarn markets. Those weavers who could grow their own flax, have it prepared and spun by their own families, and weave it themselves, were liable to profit most in the public markets, especially if they were able, like those living in the ‘linen triangle’, to weave the finer quality linens. The system of public markets flourished and expanded with the support of the bleachers who had come to dominate the industry in the second half of the eighteenth century: they believed that if the linen markets were properly run with sealmasters to inspect the quality of the linens, they could obtain there for their bleachgreens the variety of linens that they needed to meet their orders from England.6 The competition engendered by this system of marketing promoted independence among the weavers and their families and constrained them to organise the resources of the family to produce webs of cloth for the market.

Flax has always required an abundance of cheap labour and provided work for the whole family. Even the preparation of land was labour intensive. Flax usually followed a well-manured potato crop that put the land into good heart and cleansed it of weeds. After the land was ploughed several times to produce a good tilth, women picked up any remaining clods of earth and stone and dumped them at the foot of the banks that enclosed the fields. They weeded the crop by hand and when it was ripe they worked with men to pull it, a job that was very sore on their hands. With men they rippled it to save the seed. It was, however, the men who placed it in the lint-dams for retting so that the woody core of the flax stems could be softened. Working in the lint-dams was not women’s work, perhaps because it was a very heavy and dirty job where women’s clothing would have rendered them ineffectual as well as immodest. After the removal of the flax from the dam by the men, it was the women who spread it to dry, a process known as ‘grassing’. Then the flax was ready for scutching to extract the fibre from its casing. Women beat it with a wooden ‘beetle’ to fragment this casing and then other women hung the flax over a block of wood and struck away the broken straw with long wooden blades.7 The remnants of the straw, known locally as ‘shives’ or ‘shous’, were removed by passing handfuls of the fibre through an implement known as a ‘clove’.8

The economic value of this work was calculated by several respondents for Arthur Young when he was touring Ulster in the summer of 1776 (Table 9.1). About this table, drawn up for him near Armagh, Young was careful to note:

If let to a man who should farm flax, the labour would be much higher, as it is here reckoned only at the earning, which they could make by the manufacture, and not the rate at which they work for others.

The essence of Young’s argument is that flax was an expensive crop to grow if labour had to be paid for, because fieldwork costs had to compete against spinning wages.

| Expense of an acre of land under flax | ||||

| £ | s. | d. | ||

| Rent | 0 | 14 | 0 | |

| Seed bought from 10s. to 13s. a bushel, average 12s.: 3 bushels | 1 | 16 | 0 | |

| One ploughing | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

| Carrying off the clods and stones by their wives and children, 6 women, an acre a day | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Weeding, 10 women an acre in a day, 4d | 0 | 3 | 4 | |

| Pulling by women and children, 12 at 4d | 0 | 4 | 0 | |

| Rippling by men and women, say 4 men at 10d | 0 | 3 | 4 | |

| Laying it in the water according to distance, say | 0 | 5 | 0 | |

| Taking it out and spreading | 0 | 5 | 0 | |

| Taking up, drying and beetling, 42 women a day at 4d | 0 | 14 | 0 | |

| Scutching 30 stone at 1s. 1d. | 1 | 12 | 6 | |

| TOTAL | 6 | 6 | 4 | |

| 30 stone at 4s. 2d. | 6 | 5 | 0 | |

Source: Hutton, A. W. (ed.), Arthur Young’s Tour in Ireland (1776–1779) (2 vols, London, 1892), vol. 1, 122.

In the second half of the eighteenth century the scutching of flax had been mechanised using water power to turn the scutching blades in scutch mills. As a result flax was taken to the scutch mills where men carried out all the scutching processes. The employment of men in mills was traditional, probably because the operation of corn mills and tuck mills (for finishing locally produced woollen goods) could require considerable physical strength to manage cumbersome machinery or move heavy weights and bags. Many men were available for employment after the end of the grain harvest whereas women would be busy spinning yarn. Although it was reckoned about 1800 that a scutch mill serviced by men and boys could do more work than a dozen women,9 it is probable that flax intended for the making of fine linens was scutched and hackled at home. Young was told in Portadown:

In general they scutch it themselves and it is cheaper than the mills. Mr Workman has paid 1s. 6d. for it by hand, and 1s. 1d. to the mills, and found the former cheaper; more flax from hand and much cleaner.10

This was said to be quite a common practice even as late as 1870.11 Skilful hand scutching and hackling greatly reduced the amount of waste and best prepared the flax for spinning. For hackling it was reckoned worthwhile to employ a skilled craftsman and there were said to be many itinerant hacklers. One commentator remarked about the use of the hackling pins for combing out the fibres: ‘The most experienced hands only attempt to work the finest hackle, which is very close, and a nice matter to perform well.’ Spinning, however, was women’s work. Many stories were told about the skill of famous women spinners and some of their achievements are recounted by McCall in the third edition of his book Ireland and her Staple Manufactures (Belfast, 1870): some specimens said to be much inferior to the finest yarns produced half a century earlier were awarded prizes at the Great Exhibition of 1851.12

Ireland had a long tradition of skill in spinning. In 1636 Lord Deputy Wentworth had observed that Irish women were ‘naturally bred to spinning’ and in 1673 Sir William Temple added: ‘No women are apter to spin it well than the Irish’.13 It was the task of successive governments to enforce standards that would guarantee the length of the yarn exposed for sale. By an act of 1705 (2 Anne, c. 2) flax yarn was to be reeled on a standard reel 2½ yards in circumference with 120 of these threads in a cut and 12 cuts in a hank so that each hank contained 3,600 yards; four hanks made up a spangle. The act proved very difficult to enforce. In 1723 even the possession of unstatutable yarn was made a punishable offence but as late as the 1780s the transgression persisted.14 The Linen Board as early as 1717 had regulated and patronised spinning schools to propagate skills and precepts throughout the country15 but as early as 1724 it was decided that no more schools should be allowed in Ulster, except for the county of Fermanagh only, because ‘the art of spinning had made so great a progress in the province of Ulster’.16 Nevertheless, spinning was carried on in the ‘charter schools’ provided by the Incorporated Society for Promoting English Protestant Schools in Ireland, and the sale of the yarn provided much of the finance required to maintain the children and their teachers.17 In providing many families with an income or a supplement to it, the domestic spinning industry required them to meet government regulations and commercial standards. As women learned that they could earn more for quality yarns, output of them increased. Arthur Young noted that spinning and weaving for cambric (such as was used for making handkerchiefs) was being carried on around Lurgan.18 Within thirty years it had spread to the surrounding towns of Lisburn, Banbridge, Tandragee and Dromore.19 In 1822 the comment was made:

In the north of Ireland … the object of every person who has flax, is to have it of as fine quality as he can; and the spinner’s object is to spin it as fine as they can, because it pays a better price; and the manufacturer’s object is to weave the finest linen that he can; for which reason, the coarse article in the north of Ireland is made only of the refuse of the flax.20

Of every stone of flax that emerged from the rough hackling process it was reckoned that about a quarter could be spun into the fine yarn needed for the finest webs whereas about a half was fit to be woven into a medium quality linen. The remainder of the yarn, known as tow, was hackled again and spun into tow yarn that was woven and made into work shirts.21

Although it was the family that was idealised in contemporary literature as the unit of production, it would have been more accurate to talk in terms of the household. Many families employed and lodged in their homes young men as weavers and unmarried women or widows as spinsters. They required them to carry out other duties in the house and around the farm. In his tour through the northern counties of Ireland in the summer of 1776 Arthur Young commented regularly on this phenomenon. South of Derry city he found: ‘The spinners in a little farm are the daughters and a couple of maid-servants that are paid 30s. a half year, and the common bargain is to do a hank a day of 3 or 4 hank yarn.’ Around Lisburn ‘the spinners are generally hired by the quarter, from 10s. to 12s. lodging and board and engaged to spin 5 hanks of 8 hank yarn in a week.’ For such fine yarn a skilled spinster could earn up to 8d. per day but for the coarser yarns 4d. to 6d. was more likely, while a girl of 12 could earn 1½d. or 2d. per day, and a girl of seven might get a penny. In these cases, however, the spinster had to provide her own board and lodging.22

The relationship between ‘the family’ and ‘the household’ in this context is worth further scrutiny. Those members of the household who were not also members of the nuclear family were required to fill an economic vacancy in the family, that is to undertake duties that would have been carried out if the family had possessed someone with the relevant skills and experience. Not only were women cheaper to employ, they were also more versatile around the house and even the farm as long as heavy work was not sustained or excessive. The ability of a family to provide and manage the work of its own members depended much on its economic base. Poor families had to labour for others who could provide them with work and so they were likely to shed their children early. There were, however, considerable benefits to be gained by those families that could organise themselves into an effective production team. They were usually families that had managed to obtain a lease of their farm, no matter how small, because the possession of a lease gave a family status and self-confidence as well as an instrument for securing loans. As the lease aged, the fixed rent became a smaller proportion of the family’s expenditure because the value of land rose steadily throughout the eighteenth century.23 In such circumstances a family might sublet part of its farm to pay for the hire of a cottier at the loom or in the field. In many districts throughout the north of Ireland women prepared and spun yarn for sale in the market because their menfolk concentrated on their farming duties and would not weave. As the century progressed, how-ever, more men took up the weaving of coarse linens when work on the farm was slack, or apprenticed their sons to the trade.24 It is probable, too, that many women engaged at busy times in weaving. It was believed in the years before the fitting of the flying shuttle to looms about 1815 that the loom was too heavy for women, especially as the weaver was required to stand and stoop over the cloth.

It may be that the greater widths of cloth required for the commercial markets made the task of weaving too strenuous for women. Yet it had long been the practice for women to weave the woollens and linens needed by their own families. Or it may be that the introduction of the lighter cotton loom equipped with the flying shuttle and using mill-spun yarn encouraged women to take up weaving. The absence of direct evidence for weaving by women throughout the eighteenth century probably has much to do with the fact that men were responsible for selling the webs as well as purchasing yarn in the markets. In parallel situations in Lancashire and in the American colonies women were to be found among the weavers.25 Indeed the American case is especially interesting because, although the introduction to a recent exhibition refers to both male and females working in New England, all the specimens attributable to individuals were woven by women: they were probably made for use in the weavers’ homes.26 In general, however, in the Irish industry women concentrated on spinning to keep the weavers supplied although they could have been required also to assist the weaver at the loom if a boy was not available.

In any consideration of the key role of the family and the family firm in the domestic linen industry, attention has to be paid to the family cycle. It has often been suggested that possession of skills in spinning and weaving enabled young people to marry early and set up home together. Their success, however, would depend to a great extent on the situation in their respective homes. It has to be remembered that these young people were in effect withdrawing from existing linen production units. If they had played their part at home and the omens were propitious, they might not only count on the goodwill of their parents but might even be given at least a subdivision of a parent’s holding on which to build a dwelling, as well as a dowry with the bride to establish the new family. With these essentials and the continuing support of their families they stood a good chance of establishing a new family. Without them they were very vulnerable to misfortune especially in the aftermath of the birth of their first children, when the woman’s earning capacity was seriously reduced, so that many slipped easily into debt that brought them into the clutches of moneylenders and unscrupulous dealers. At the same time it was still possible for poor families to work themselves up the social ladder. A landmark in their success would be the purchase of an interest in a lease because its possession provided both status and security.27

It is important to point out that much of the evidence presented in this study relates to the eighteenth century when the domestic linen industry steadily increased until it came to dominate the economy of the north of Ireland and seriously altered its social structure. The process in County Sligo was described in 1766 by a local member of Parliament:

the present great price of land is principally owing to the cottage tenants, who being mostly Papists, have long lived under the pressure of severe penal laws and have been enured to want and misery. The linen manufactory in its progress opened to these such means of industry as were only fitted to penurious economy. Three pence a day, the most that can be made by spinning, was an inducement fit only to be held out to women so educated. The earning was proportioned to their mode of living and became wealth to the family. In mountainous countries the grazier had formerly driven them [these people] to the unprofitable parts. Here they placed themselves at easy rents for the demand for cattle in these days was not more than the good lands could supply. The cottager, necessitated to try all means of drawing a support from his tenement, has in the course of his industry discovered that his mountain farm with the amelioration of limestone gravel, is productive both of corn and potatoes, and in succession afterwards of flax equal to the low grounds. But the labour of this is great and fit only for people so trained to hardship. The home consumption of cattle increasing with the wealth of the country, the markets of Great Britain open, and the colonies more extended and more populous, have multiplied the demand and given at last a value even to the mountains for pasture. But here the cottage tenant, abstemious and laborious, is enabled by the industry of his family to outbid the grazier. They cant each other and give to land the monstrous price it now bears. But from the inland countries where all the land is good the cottagers were early banished so that land only rises there in proportion to the additional demand for cattle. Besides that, most lands in such countries are fitter for pasture than for tillage. Thus we flourish and land continues to bear its present price and will do so till an increase of wealth shall create new desires in the cottager, and that small profit which now gives excitement to his industry shall cease to be an object. Then the factors must be content with smaller profits, some new manufacture must succeed, or we must return to pasture and land fall to a lower price.28

The scale of these changes makes it very difficult to generalise about the social characteristics of earlier centuries. Even the importance of the family cannot be taken for granted. The same member of Parliament had commented in 1760 that as a result of the economic changes, ‘A family now has a better bottom than formerly: residence is more assured and families are more numerous as increase of industry keeps them more together.’29 It was this cohesion of the family that gave the mother status and authority both at home and in society. Without this role a woman’s value was dependent on her earning ability within the community. Women did many of the everyday jobs that their physical strength allowed. They were not allowed by men to undertake strenuous work that might injure them. That reality deprived them of equal status in a world where physical strength was esteemed.

1 First published in Margaret MacCurtain, and Mary O’Dowd, (eds), Women in Early Modern Ireland (1991), pp. 255–64.

2 Postan, M.M., The Medieval Economy and Society (London, 1972), pp. 190–2.

3 Longfield, A.K., Anglo-Irish Trade in the Sixteenth Century (London, 1929), pp. 77–93; Wadsworth, A.P. and Mann, J. de L., The Cotton Trade and Industrial Lancashire 1600–1780 (Manchester, 1931), pp. 5, 6, 11, 13, 46–7.

4 Cullen, L.M., Anglo-Irish Trade 1660–1800 (Manchester, 1968), p. 50.

5 Cullen, L.M., An Economic History of Ireland since 1660 (London, 1972), pp. 39–42, 59–66, 105–6.

6 See pages 132 to 142.

7 See pages 50 and 51.

8 Lucas, A.T., ‘Flax cloves’, Ulster Folklife 32 (1986), 16–36.

9 Coote, Sir C., A Statistical Survey of the County of Monaghan (Dublin, 1801), pp. 197–8.

10 Young’s Tour, vol. 1, 126.

11 McCall, H., Ireland and her Staple Manufactures (3rd edn, Belfast, 1870), p. 356.

12 Ibid., pp. 366–8.

13 Horner, J., The Linen Trade of Europe during the Spinning-Wheel Period (Belfast, 1920), pp. 16, 22.

14 Gill, C., The Rise of the Irish Linen Industry (Oxford, 1925), p. 68.

15 Ibid., pp. 75–6; Corry, J., Precedents and Abstracts from the Journals of the Trustees of the Linen and Hempen Manufactures of Ireland (Dublin, 1784), pp. 19–20.

16 Corry, op. cit., p. 70.

17 Harris, W., The Antient and Present State of the County of Down (Dublin, 1744), pp. 17, 77. Horner, op. cit., pp. 99–100 for a summary of a 1751 report on the spinning schools.

18 Young’s Tour, vol. 1, 128.

19 See Appendix 4.

20 1822 Linen Laws Report, p. 486.

21 Young’s Tour, vol. 1, 122, 126–7, 130, 139, 152, 161.

22 Ibid., pp. 122–204, especially 133, 174.

23 Crawford, W.H., ‘Landlord–tenant relations in Ulster 1609–1820’, Irish Economic and Social History 2 (1975), 12–18.

24 McEvoy, J., A Statistical Survey of the County of Tyrone (Dublin, 1802), pp. 135–56.

25 Wadsworth and Mann, op. cit., pp. 336–7.

26 All Sorts of Good Sufficient Cloth: Linen-Making in New England 1640–1860 (Merrimack Valley Textile Museum, North Andover, Massachusetts, 1980): a catalogue for an exhibition.

27 See the case argued in Serious Considerations on the Present Alarming State of Agriculture and the Linen Trade, by a Farmer (Dublin, 1773) in vol. 377 of the Haliday Pamphlets in the Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, published here as Appendix 3.

28 National Library of Ireland, O’Hara papers. Some of this collection has been photocopied by the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland and this important manuscript is T2812/19: ‘Charles O’Hara’s account of Sligo’.

29 Ibid.