To successfully make the jump across the pond to explore your ancestral origins, you will need two key pieces of information: the immigrant’s original name and hometown. Sounds simple enough, right? In reality, pinpointing these basic pieces of your family puzzle can be one of the most challenging aspects of the research process. In this chapter, we’ll explore strategies and sources on this side of the ocean to obtain those critical clues.

Chances are good that your immigrant ancestor went by a different name after coming to America than he did in the old country. Especially during that transition time between the Old and New Worlds, changes were bound to happen—be they variant spellings, translations, or just phonetic garbles. You may encounter a number of spellings. In order to correctly identify the immigrant, gather records made by or for the ancestor for the span of his life (from birth to marriage to death).

Name changes generally occurred after immigrants arrived in the United States or Canada, so expect your ancestors to appear in earlier records—including their passenger arrival lists—with their Polish, Czech, or Slovak moniker. This is where it helps to understand Polish, Czech, and Slovak naming practices, which we will review in chapter 7.

The “Americanizing” of immigrants’ names could take several forms. These are the most common scenarios to watch for—any or all of them could apply to your immigrant ancestor.

Polish, Czech, or Slovak immigrants sometimes “translated” their given names to the English equivalents. For example, Jan became John, or Katarzyna became Katherine. An immigrant with the surname Krejči might opt for Taylor in America. Use Behind the Name <www.behindthename.com> to research name translations; the Polish Genealogical Society of America also has a handy guide with Polish, Latin, and German versions of English given names at <pgsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/FirstNameTrans.pdf>. Some common changes to names are caused by

To further your understanding of the complexity of Eastern European surnames, download and read “Mutilation: the Fate of Eastern European Names in America” by William F. Hoffman <pgsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Mutilation.pdf>.

The number of name variations you’ll encounter for a single ancestor can be mind-boggling. That’s why it’s helpful to create a list of all potential variants for each surname you are researching. Refer to the list when searching online databases and printed indexes to ensure you don’t miss your ancestor.

It’s a common misconception that officials at Ellis Island changed immigrants’ names. In reality, immigration officials didn’t record arriving passengers’ names—they just checked lists filled out at the port of departure. Read immigration historian Marian L. Smith’s article “American Names: Declaring Independence” <www.ilw.com/articles/2005,0808-smith.shtm> for more on immigrants’ names.

Here’s an example: For one of my Slovak ancestors, Verona Straka, I found the following variations:

I created this chart to help me keep track of all the surname variations in just one glance. As I find additional variations, it’s easy to go back to the list and record them.

Making a chart of first name variants is useful, too. Be sure to include nicknames (such as Lizzie, Liz, Betty, Betsy, or Beth for Elizabeth, or Johnny, Johnnie, Jon, Jack, or Jackie for John). Use the Name Variants Worksheet at the end of this chapter to record your own list of name variations.

To find records from the old country, you will need to know where your family lived. Knowing just the name of a province or nearby large city (Warsaw, Kraków, Prague, Prešov, etc.) isn’t enough because repositories file records by locality. Many American researchers proceed under the illusion that an archivist in Poland, the Czech Republic, or Slovakia can tell them where their ancestor was born. It’s pretty simple: If you don’t have the exact birthplace of your ancestor, you can’t successfully research records from Poland, the Czech Republic, or Slovakia.

How do you get it? You’ll be looking for this information in a variety of records. Just remember: When it comes to pinpointing an ancestor’s birthplace, not all records are created equal. See the Sources for Town of Origin sidebar. Note that some of your ancestors may have listed their town of origin as a big city for convenience. Just as someone might list his hometown as Pittsburgh rather than his actual hometown of McKeesport since more people know where Pittsburgh is, your ancestor may have used a larger, more recognizable city as a point of reference.

Before attempting to trace Polish, Czech, or Slovak ancestry abroad, exhaust all US sources first. This will help you find the right people overseas. Here, we’ll review the most important records and the immigration clues they contain. The Family Tree Magazine Records Checklist, downloadable from <www.familytreemagazine.com/upload/images/PDF/recordschecklist.pdf>, provides a handy roster to ensure you’ve checked all available sources.

You’ll find many clues to help you identify immigrants in US census records, taken every ten years by the federal government. Censuses from 1790 to 1940 are publicly available (except 1890, of which only fragments survive) on websites including Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org, and Mocavo <www.mocavo.com>. Enumerations through 1840 list only heads of household by name; from 1850 on, they name every member of a household. For Polish, Czech, or Slovak immigrants, the best data come from 1900 onward (see the Immigration Clues in US Censuses sidebar).

This chart outlines US sources that might name your ancestor’s town of origin, grouped from highest probability of giving a specific town name to least. While you should seek out all these records for your immigrant ancestor, use this table to prioritize your search and set expectations.

In general, census records provide only a country of origin. During the 1800s and until after World War I, this would be Austria for Czechs and either Austria or Hungary for Slovaks. For Polish researchers, the country in the census tells you whether the family came from German, Russian, or Austrian Poland (see chapter 4 for more on the partitions of Poland).

For example, the 1930 census record of the John Figlar family shows John’s birthplace as Czechoslovakia and his immigration year as 1921, giving a time frame to search for his passenger arrival list (image A).

The 1930 census gives John Figlar’s birthplace as Czechoslovakia. Census records provide a country of birth, but generally not a town.

Sometimes you’ll get a more specific location—for example, Ruthenia instead of Austria or Hungary (indicating possible Carpatho-Rusyn ancestry). Rarely will the census list an ancestral village.

When using censuses, keep in mind that your Polish, Czech, or Slovak ancestors likely spoke limited English and, in general, were suspicious or fearful of government officials—in Europe, a visit from a government representative might involve collecting more money for taxes or conscripting young men into the army for up to twenty-five years. If the person lied or made up the information, the census taker had no way of knowing. If a family was not home when the enumerator arrived, it was not unusual for a neighbor to provide information. Therefore, mistakes and misinformation were not uncommon. Use the census to establish a sense of place for your family and focus your search for other sources, such as immigration and naturalization records.

Here’s a brief summary by census year of the columns that can clue you in to immigrant origins.

If your ancestor became a US citizen, the resulting records are a place to glean clues about his origins. Most Polish, Czech, and Slovak immigrants would have followed a two-step process: filing a declaration of intention to become a citizen (first papers), then once residency requirements had been met, filing a petition for naturalization. Your ancestor could go to any courthouse—municipal, county, state, or federal—to file and could even start the process in one court and finish it in another. So you’ll want to check records from all courts near where your immigrant arrived or settled.

Starting in 1906, the federal government standardized naturalization paperwork. Declarations of intention (image B) contain these critical immigration details:

A declaration of intention contains information about an ancestor’s origins, including hometown.

Petitions for naturalization (image C) contain similar immigration information. They lack the last foreign residence, but add these helpful tidbits:

A petition of naturalization, issued once your ancestor had met certain requirements, also contains valuable information.

Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org, and Fold3 <www.fold3.com> offer some digitized and searchable naturalization records. The easiest way to locate online records from your ancestor’s locality is via Online Searchable Naturalization Indexes and Records <www.germanroots.com/naturalization.html>, which has links organized by state. Many more naturalization records have been microfilmed; you can access those via local FamilySearch Centers and (for federal courts) the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) regional facilities. Failing that, try city, county, regional, and state archives. Naturalizations made in municipal courts might be in the town halls or city archives of major cities such as Baltimore, Chicago, and St. Louis. You can request post-1906 naturalization documents from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) <www.uscis.gov/genealogy> for a fee, but expect a long wait time.

When your ancestor decided to leave the old country, he usually bought his passage from a local transportation agent or received a ticket from a contact in America. Most immigrants sold their personal effects and livestock or borrowed from the local moneylender to raise the necessary funds. After 1880, steamship travel was the common mode of transportation, and most Polish, Czech, and Slovak immigrants sailed from a German port—usually Hamburg or Bremen—on the most popular lines: the North German Line and Hamburg-American Line.

It’s worth looking for a record of your ancestor’s departure as well as his arrival. You can access Hamburg’s passenger departure lists from 1850 to 1934 on Ancestry.com and FamilySearch microfilm. Unfortunately, Bremen’s passenger lists were destroyed, except for 1920 to 1939 (search those <www.passengerlists.de>).

The voyage might have included a stopover at another port, such as Liverpool or Southampton. If that’s the case, you’ll need to look for your ancestor on “indirect” departure lists. You also might find your ancestor in Findmypast’s subscription database of twenty-four million outbound passenger lists from British ports covering 1890 to 1960 <search.findmypast.com/search-world-records/passenger-lists-leaving-uk-1890-1960>.

Polish, Czech, and Slovak immigrants entered America through various ports, especially New York (at Castle Garden starting in 1855 and Ellis Island from 1892), Baltimore, Boston, and Philadelphia. Beginning in 1820, the federal government supplied preprinted manifests to document passengers on US-bound ships. These were called customs lists until 1891, then passenger-arrival lists after (image D). The volume of information collected on passenger lists increased over time, meaning records for late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Polish, Czech, and Slovak immigrants will be the most detailed.

Passenger lists, though filled out at ports of departure, sometimes contain an ancestor’s place of origin.

NARA has microfilmed passenger lists from all US ports in its custody, including these common Eastern European entry points:

All of the NARA-held passenger lists are available on microfilm via FamilySearch, as well as searchable and digitized on Ancestry.com. For the port of New York, also try <www.libertyellisfoundation.org> and <www.castlegarden.org>. Steve Morse’s One-Step Webpages site <www.stevemorse.org> offers additional flexibility for tapping those online passenger list databases, allowing you to search phonetically, by town, and more. It’s a good tool to try when you struggle on the hosting sites (note that you still need a subscription to view results on pay sites). When names are misspelled or mistranscribed, searching by village might be the only way to locate your immigrant ancestor.

Vital records, of course, are the building blocks of all genealogical research. When identifying and researching a Polish, Czech, or Slovak immigrant, these are the key details to look for in government-issued vital records:

If your Polish, Czech, or Slovak ancestor traveled back to the old country during one of the periods in which passports were required, you may find his application. Ancestry.com has a searchable online database of US Passport Applications, 1795–1925 <search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1174>.

In addition to government vital records, look for church baptismal, marriage, and burial records. These often have more details than their civil counterparts because the priest, minister, or secretary knew the family. And because immigrant communities often had their own churches, knowing the church your ancestors attended might hint at where your family came from. Many US Polish, Czech, and Slovak parishes scrupulously recorded their parishioners’ exact places of origins in marriage records and on the American-born children’s baptismal certificates. The US parish is usually one of the best places to secure a geographical link to your European place of origin.

Polish immigrants were predominantly Roman Catholic, and their US parishes often recorded baptisms and other documents in Latin. For marriages, the Catholic Church might have granted a dispensation for an underage or mixed-religion relationship. Dispensations are kept in diocese archives. Remember that godparents usually were relatives and might come from the same village as your ancestors.

You’ll need to contact a church or diocese directly to inquire about its records. Search Google by parish name and locality or use an online directory such as USA Churches <www.usachurches.org>. If you’re unsure of your ancestors’ place of worship, look in city directories for possible parishes. When approaching a parish for records, remember that sacramental records aren’t necessarily public—it’s at the priest’s discretion to allow access. Be prepared to make a donation to the church in honor of your ancestors, but do not offer to pay the priest—a subtle but important distinction.

Obituaries, especially those published in the first half of the twentieth century, often give an immigrant’s place of birth—though beware misspellings from survivors who report the information. Numerous websites offer online access to obituaries, including Genealogy-Bank <www.genealogybank.com> (subscription required), Legacy.com <www.legacy.com>, Obituary Central <www.obitcentral.com>, Obituary Daily Times <obits.rootsweb.ancestry.com>, USGenWeb Archives Obituary Project <www.usgwarchives.net/obits>, and USGen-Web Archives <searches.rootsweb.ancestry.com/htdig/search.html>. The Polish Genealogical Society of America <www.pgsa.org> has the death notice indexes from Dziennik Chicagoski, Chicago’s Polish daily newspaper, and Baltimore’s Jedność-Polonia. The First Catholic Slovak Union publishes obituaries in its Jednota newspaper. Use Chronicling America <chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/newspapers> to identify other newspapers published in your ancestors’ area that you can access on microfilm.

If you feel you’ve exhausted all the potential records and are still having trouble finding your immigrant ancestor, try the collateral and cluster approach introduced in chapter 2. This is also called the “FAN club principle” because it involves researching the “Friends, Associates, and Neighbors” of your immigrant ancestor. Pay special attention to the FANs listed here.

While it’s tempting to focus on obituaries for immigration information, don’t stop there. You may find mention of a village in articles about your ancestors or their businesses, articles about family reunions recounting history back to the boat, and genealogy columns. Again, use Chronicling America to identify target papers, then see if you can access them on GenealogyBank, Newspapers.com <www.newspapers.com>, Google News Archive <news.google.com/newspapers>, or Elephind <www.elephind.com> before seeking out microfilms.

Also, don’t forget about foreign-language and ethnic-focused newspapers, which can help with tracing an immigrant’s origins. Two excellent repositories for these are the Balch Institute, located at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia <www.hsp.org>, and the Immigration History Research Center, located at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis <www.umn.edu/ihrc>.

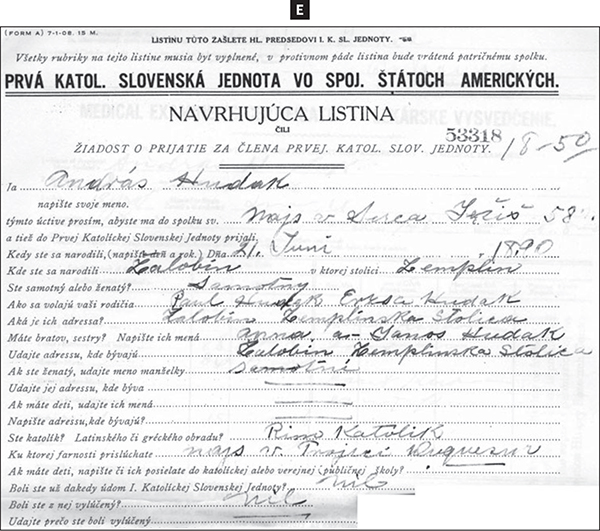

Many Polish, Czech, and Slovak immigrants started their own fraternal benefit societies and social clubs to help preserve their heritage and to provide insurance in the event of the family breadwinner’s death or serious injury. Perhaps your ancestor belonged to the Polish National Alliance, the Polish Falcons of America, the First Catholic Slovak Union of America, the Czech Catholic Union, the National Slovak Society, Sokol, or another organization. You can find a complete list of fraternal organizations at <www.exonumia.com/art/society.htm>. Organizations’ records might include membership applications (image E), death benefit claim forms, and meeting minutes. Many fraternal organizations published member updates in newsletters, and some even established their own printing presses for publishing newspapers. If the group still exists, contact the local chapter or the national office to ask about historical records. Some organizations have turned over records to research repositories. See appendix H for a list of some of these societies.

Your ancestor’s application to an ethnic fraternal organization in the United States can provide information about where your ancestors hail from.

Despite all these research possibilities, not every ancestor left an adequate breadcrumb trail to a village of origin. In some cases, you’ll have information on a county or district name, but no village within that area. Depending on the size of that jurisdiction and the time you can put into the project, you might be able to sift through all of the church records for the particular locality. While that might require a lot of work, the payoff is big; with your immigrant ancestor’s original name and hometown, you’re able to travel back in time to the old country to look for his records in Europe.