Top Ten Polish Surnames

These are the most common surnames in Poland today.

Names are a common roadblock in Polish, Czech, and Slovak genealogical research. It could be you don’t have a consistent or correct spelling. More often, you know the right name but can’t seem to find it in an index. Such name stumpers can be the result of foreign spelling, foreign accents, bad handwriting, nicknames, and name changes. Playing the “name game” is inevitable in Eastern European genealogy, as the name you know your ancestor by or see in North American records may or may not be the one he or she used back home.

As you will see, language—whether Polish, Czech, Slovak, Latin, Hungarian, German, or Russian—plays an important role when determining and deciphering names. This chapter will look at how the Polish, Czech, and Slovak languages relate to surnames and naming patterns, as well as ways to work around these potential roadblocks. Be sure to have your Name Variants Worksheet from chapter 3 handy to piece together your family’s name puzzles.

Surnames were created out of necessity—they came about gradually as populations grew and contact between isolated groups of people increased. People were generally referred to by their first names. Last names developed to distinguish one person from another. For example, a small village could have many young men named Jan. To avoid confusion, the local populace would attach a descriptor to distinguish one Jan from another. Surnames usually fall into four basic categories:

Some examples of the surnames from my own family tree include Figlyar (trickster, jokester) and Alzo (from also, meaning “lower”). Nicknames may have been added to further distinguish people. In addition, surnames take different forms with the language and culture.

In the 1800s and earlier, spelling was not standardized as it is today. As a result, multiple phonetic variations to a name’s spelling were common. Due to colloquialisms and regional dialects, name spellings changed depending on where you were. You may likely discover different spellings or versions of the family name. For example, my grandfather spelled his name Figlar, but one of his brothers spelled it Figler. Another family name, Straka, appears as Sztraka (Hungarian spelling) and in American records as Stracha or Strake.

Teasing your Polish, Czech, or Slovak ancestors’ names out of online databases can be challenging. When you’re confused about where to look next, keep these five factors in mind.

Be aware of the way the immigrant’s original language sounded, because it may account for some of the incorrect spellings you will encounter. For instance, a ch combination in one language may sound like an English ck or k instead. In German, the sound of an initial consonant b often sounds like a p. Take these pronunciations as well as unique letters into consideration when looking at indexes or search results.

Don’t overlook your ancestors’ nicknames, middle names, or native first names from their home country. Ludwig, Louis, Lewis, or Lou could all be correct first names for one individual. Some researchers get stumped looking for Uncle Bill or Aunt Stella only to discover that they should have been looking for Bołesław or Stanisława.

When last names were being standardized, each language usually had a single word for commonly used descriptors—for instance, a miller using his profession as a surname would have had Müller in German or Molnár in Hungarian. As a result, individuals found ways of personalizing their surnames. While the main Slovak surname for miller was Mlynár, some Slovaks used the variations Mlynarčík, Mlynarovič, Mlynárik, Mlynka, Mlynkovič, Minár, Minárik, Minarovič, Mlynček, Mlynčár, and Mlynský to distinguish themselves.

Some online search forms allow for phonetic name searches. One such option is Soundex, a phonetically based surname “code” that captures similar-sounding names. Soundex is an American invention, however, and doesn’t always handle Eastern European surnames well. Alternative Soundex schemes have been developed to overcome this, most notably the Daitch-Mokotoff Soundex system. If a website offers options for Soundex or “sounds like” searches, give those a try.

The Polish, Czech, and Slovak languages have letters that the English alphabet does not, and those letters’ pronunciations can create roadblocks for English speakers. For example, the Polish Ł/ł often confuses non-Poles—it’s pronounced like an English W. It may be transcribed as L/l in English, or the lowercase version may become the similar-looking lowercase t. Similar issues occur with the Polish ą—pronounced ahn but often transcribed as a simple a in English. Remember these letters, too, when you’re searching foreign-language indexes and websites—they may be the reason you’re not finding what you are looking for.

In addition to the search tactics we’ve covered, these resources will help you in tracking down your ancestor’s surname.

One-name studies will likely be one of your first resources in searching for your ancestor’s records. Generally, a surname’s one-name study encompasses all known variants of that surname and follows that name’s occurrences throughout history. One-name studies are especially popular in Great Britain, but you can find some for Slavic surnames. Search the Guild of One-Name Studies’ website <www.one-name.org> or use the alphabetical name listing to peruse registered names <www.guild-dev.org/namelist.html>. You can also register with the guild (there is a sliding-scale membership fee based on country) and, if you’re so inclined, add a study name. Other general resources include the RootsWeb Surname Resources page <resources.rootsweb.ancestry.com/surnames> and Cyndi’s List: Research <www.cyndislist.com/personal>.

How do you know when you’ve found the right Jakub Novotný? Make a timeline of all you’ve learned about your ancestor so you can see at a glance if the facts (birth dates, locations, etc.) in new records match what you know. Additionally, “anchor” your ancestor with a relative who has an uncommon name. For instance, Jakub’s sister Bohumila will be easier to ID in records, and you’ll know you have the correct family when you find her.

Surnames may be wrong, but DNA doesn’t lie. A Y-DNA test can show whether two same-named men are related, and if so, estimate the number of generations that separate them from their most recent common ancestor. Family Tree DNA <www.familytreedna.com> is the leading Y-DNA testing company; check its website for surname studies. Those with Czech roots will want to read about the Czech American DNA study at <www.cgsi.org/content/czech-american-dna-study-leo-baca>, which has a listing of surnames that have participated in the study. In chapter 13, you will learn more about using DNA as a tool when you get stuck.

Polish surnames developed around the practices described earlier in this chapter. Some Polish surnames are unique to certain regions, while others are found throughout the country. To determine the frequency of a particular Polish surname and its geographical distribution by province, consult Słownik Nazwisk Współcześnie w Polsce Używanych (Dictionary of Surnames Currently Used in Poland) edited by Kazimierz Rymut (Polska Akademia Nauk/Instytut Języka Polskiego, 1992). Compiled from a 1990 Polish government database, this was the first comprehensive compilation of Polish surnames, covering 94 percent of the population. This Polish-language work is searchable at <www.herby.com.pl/indexslo.html>. Before using it, consult William F. Hoffman’s step-by-step guide <www.jri-poland.org/slownik.htm> to learn how to enter names for best results and interpret the results. You’ll also want to use Google Translate <translate.google.com> to convert the site to rough English.

Refer to the following free resources for help with surname meanings and distributions:

These are the most common surnames in Poland today.

As we discussed earlier, it was common for Polish immigrants to “translate” their first and last names to English equivalents or alter the spellings to look more American after they settled in their new home. To trace your family in Poland, you need to figure out the original Polish names. Consulting the surname databases described here can help you “repair” personal and place-names recorded incorrectly in American sources. It also helps to gain familiarity with Polish language basics: When you know the sounds associated with certain letters and letter combinations, you’ll be able to devise alternative search terms.

You’ll also need to know Polish naming practices. Polish Roman Catholics, for example, would often name a child after a saint whose feast day was celebrated on or near the baby’s date of birth or baptism. Several books can help you find the proper spellings of surnames and determine given names in German, Hebrew, Latin, Polish, Russian, and Ukrainian: Polish Surnames: Origins and Meanings, second edition by William F. Hoffman (Polish Genealogical Society of America, 1997) and First Names of the Polish Commonwealth: Origins and Meanings by William F. Hoffman and George W. Helon (Polish Genealogical Society of America, 1998). In addition, Going Home: A Guide to Polish-American Family History Research by Jonathan D. Shea (Language and Lineage Press, 2008) includes an index of first names most often seen in Polish research, prepared by Hoffman.

Polish letters with diacritical (accent) marks—ą, ć, ę, ł, ń, ó, ś, ź, and ż—were often misinterpreted (even in parts of the old country, where records weren’t kept in Polish). You might find the given name Władysław transcribed as Wtadystaw, or the surname Zdziebko transcribed as Fdziebko because the Z was written in the European manner with a slash through the middle, making it look like an F. See appendix A for help with the Polish language, and chapter 14 for an example of how the spelling of Polish surnames can change (even beyond the grave).

The countries surrounding the modern Czech and Slovak republics (Germany, Hungary, and Poland) strongly influenced local names. As in those cultures, Czech and Slovak names generally consist of a given name and a surname. In the Czech lands, the state typically only recognized these two names, though parents might choose additional names (e.g., middle names) at baptism and individuals may adopt new supplementary names at confirmation (e.g., confirmation names). Most Slovaks also do not have an official middle name. And as in other Western cultures, women in the Czech Republic and Slovakia typically adopted their husbands’ surnames upon marriage.

These are the most common surnames in the Czech Republic today.

These are the most common surnames in Slovakia today.

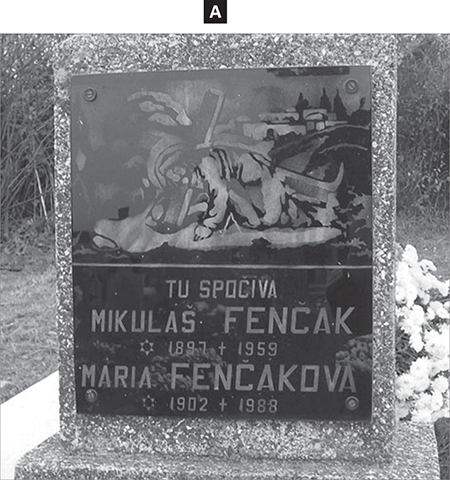

Surname spellings often vary in grammatical context. For example, male Czech surnames may end in -ovec or -úv, while Slovak names may end in -ula or other suffixes. You may encounter patronymic surnames derived from the father’s name, such as Štěpánek (meaning “little Stephen,” indicating a forefather named Stephen); other surnames reflect social status (Král, meaning “king”), personal features (Straka, meaning “bird” or “magpie”), or trade/occupation (Bača, meaning “shepherd”). Czech and Slovak female surnames typically have the suffix -ova at the end (such as Fenčakova in Slovak, as shown in image A). Learn more about surnames in books from the Czechoslovak Genealogical Society International <www.cgsi.org/store/books?topic_id=31>.

Slovak women’s surnames often carry the suffix -ova, as shown on this tombstone for Maria and Mikulás Fenčak in Poša, Slovakia.

Like Poles, Czech and Slovak Orthodox and Catholic families frequently named their children for saints. Visit Behind the Name for explanations of common Czech and Slovak given names. Also, learn to recognize regional and cultural translations: Great-great-grandma might appear as Elizabeth on her naturalization application, Alžbeta in Slovak parish registers, and Erzsébet in Hungarian census returns.

Having trouble finding your ancestor’s name in an index? Try writing out the name in the style of script used at the time. Would a handwritten P resemble an F? Or perhaps a J appears to you as a Y? This will help you find variations to try when searching databases and print records.

Learning Czech and Slovak naming patterns and practices will help you more easily spot spelling variations and transcription errors in records. As you can see from the sidebar of common Slovak surnames, Slovakia’s eight hundred years under Hungarian rule heavily influenced the frequency of surnames. The Slovakian and Hungarian languages exchanged words, phrases, and naming patterns with each other and with other surrounding languages, notably Croatian. This “borrowing” of names (as well as migrations of people within the Hungarian empire) caused a mixture of Slavic names. See <www.pitt.edu/~votruba/qsonhist/lastnamesslovakiahungary.html> for more on the intermingling of Slavic languages. Note that Hungarians typically put the surname before the given (first) name, so your Slovak ancestors may be sorted by their surname in some records.