2.1 Introduction

Institutional theory has been used since the 1990s to account for the influences of context on entrepreneurship (Bruton et al. 2010). Institutionalists explain that the appropriateness and activities of institutions heavily influence the development of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial behaviour, and enterprise strategies adopted in any country (North 1990; Welter and Smallbone 2011). Institutions provide the incentives structures, opportunities, and constraints for entrepreneurs (North 1990; Boettke and Coyne 2009; Aidis et al. 2012). North (1990) proposes that institutions can be formal and informal. Formal institutions include: government policies that ensure economic freedom and secure property rights; fair taxation; a fair legal/judicial system and contract enforcement; and enterprise support institutions that offer advice, training, and financial support to start-ups, which all promote entrepreneurship (Sobel 2008; Reynolds et al. 1999). Yet, formal institutions only function successfully if individuals develop a basic level of trust in the reliability of exchanges, and in sanctions and penalties prescribed. Hence, a consistent institutional framework requires both personal and institutional trust (Welter 2002). Informal institutions include codes of conduct, conventions, attitudes, values, and norms of behaviour. Broadly, culture and social relations constitute institutions (Thornton et al. 2011; Granovetter 1985). Thornton et al. (2011) assert that formal institutions are subordinate to informal institutions because the development of formal institutions is deliberately meant to structure the interactions of a society in tandem with the norms and values that make up the informal institutions. They argue further that this explains why attempts by policy makers to change formal institutions of society without efforts to change the informal institutions in compatible ways attain only marginal success.

Yet, Western literature, donor reviews, and policy documents that explore enterprise and economic activities in emerging economies, including Africa, ignore the important roles of informal institutions and instead emphasise that strong formal institutions are the prerequisites for enterprise and economic development. According to this view, entrepreneurs and investors are deterred from investing in emerging economies, particularly in Africa, due to weak formal institutions (see Bruton et al. 2010; World Bank 2018; The Economist 2016). However, these assumptions draw mainly from models in advanced economy contexts and do not fully reflect the nature and role of institutions in entrepreneurship in emerging economy contexts. In emerging economy contexts, the reliability of formal institutions and their prescribed sanctions and penalties is weak and hence institutional trust is low. As a result, informal institutions assume more importance and often substitute for and replace ineffective formal institutions leading to enhanced trust and entrepreneurship (see Welter and Smallbone 2011; Peng et al. 2008; Amoako and Lyon 2014; Estrin and Pervezer 2011). The embeddedness approach to the study of institutions and entrepreneurship highlights that entrepreneurs and firms’ activities are connected to local contexts and often entrepreneurs rely on their embeddedness in formal and indigenous institutions to develop trust in relationships in order to develop businesses (Baumol and Strom 2007; Welter and Smallbone 2011). Embeddedness implies that individuals and organisations affect and are affected by their social contexts (Granovetter 1985). As a result, entrepreneurs exploit opportunities embedded in institutional environments by developing a variety of social and business networks that is built on trust and cooperation (Chell 2007; Thornton et al. 2011). Hence, entrepreneurs in emerging economies as actors do not necessarily succumb to institutional weaknesses but rather, as actors, they respond strategically and reflexively to do business in the midst of formal institutional weaknesses (see Peng et al. 2008; Vickers et al. 2017). For example, Wu et al. (2014) show that in China, where formal market institutions are weak, state controlled-listed firms receive preferential treatment when borrowing from the banks. In response, private sector organisations rely on trust in networks and ties to access trade credit from suppliers and customers. Thus, trust in social institutions enables entrepreneurs of private firms to overcome institutional barriers in financing their activities. Amoako and Lyon (2014) also show that in Ghana entrepreneurs owning and managing internationally trading small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) avoid the courts due to the weaknesses of the legal systems and instead rely on trust and relationships in indigenous institutions, such as trade associations, to resolve disputes and enhance trade in local and West African markets. Hence the entrepreneur’s networks, relationships, and trust development enhance access to resources for smaller businesses operating in the context of weak institutions (Welter and Smallbone 2011; Wright et al. 2007).

Yet, existing entrepreneurship studies rarely present a balanced view of how entrepreneurs as agents respond to institutional constraints without unnecessary conformity and habitual behaviour. The lack of a balanced view, however, reflects a persistent debate in the social sciences about structure and agency. Structure broadly refers to ‘society’ and agency to the ‘individual’ and scholars regard them mainly as incompatible (see Giddens 1979). Some scholars take a structuralist view to explain human behaviour based on factors such as history, culture, institutions, and social class operating at the macro level and the level of analysis is society. Others take exception and instead take agency explanations as definitive, arguing that the human agent is the main actor and interpreter of social life hence the individual characteristics, goals, and beliefs form the basis of the analysis (see Elster 1982).

In the context of entrepreneurship, one group of studies focuses on agency and how individuals as heroes embark on the entrepreneurial process and thereby pays less attention to social cultural institutions, including networks and trust, that facilitate entrepreneurship (see Chell 2007). In contrast, another stream of studies is based on how structure- institutions constrain or enable entrepreneurship while ignoring the role of the individual or organisation whose agency or actions create, maintain or change institutions (see Lawrence et al. 2011). Interestingly, the debate on institutions and entrepreneurial agency becomes more puzzling in the context of emerging economies such as Africa due to existing conceptual developments that are based mainly on assumptions about how formal institutions act as constraints or enablers while paying little attention to the role of cultural institutions and the entrepreneur (see Amoako and Matlay 2015).

In this book, the author argues that ignoring part of structure (informal institutions) or agency (entrepreneur) in the debate on entrepreneurship in emerging economies may lead to misplaced practices and policies that may focus on only the formal institutions that are weak. Such practices may not be as effective as those that consider both formal and informal institutions and the entrepreneur.

In this chapter, the author attempts to marry the structure and agency divide in entrepreneurship by re-examining how institutions shape entrepreneurial activity. To do so, he reviews the literature on institutionalist approaches to entrepreneurship to emphasise the role of formal institutions and informal institutions, particularly how culture and networks influence entrepreneurial strategy and decision making. Institutions are defined as the ‘taken-for granted assumptions which inform and shape the actions of individual actors…at the same time, these taken-for-granted assumptions are themselves the outcome of social actions’ (Burns and Scapens 2000: 8).

Drawing on the structure agency debate, the author attempts to put both the entrepreneur and cultural institutions back into the debate on entrepreneurship and thus answer the key question: ‘What are institutions and how do they influence trust development in entrepreneurial relationships?’

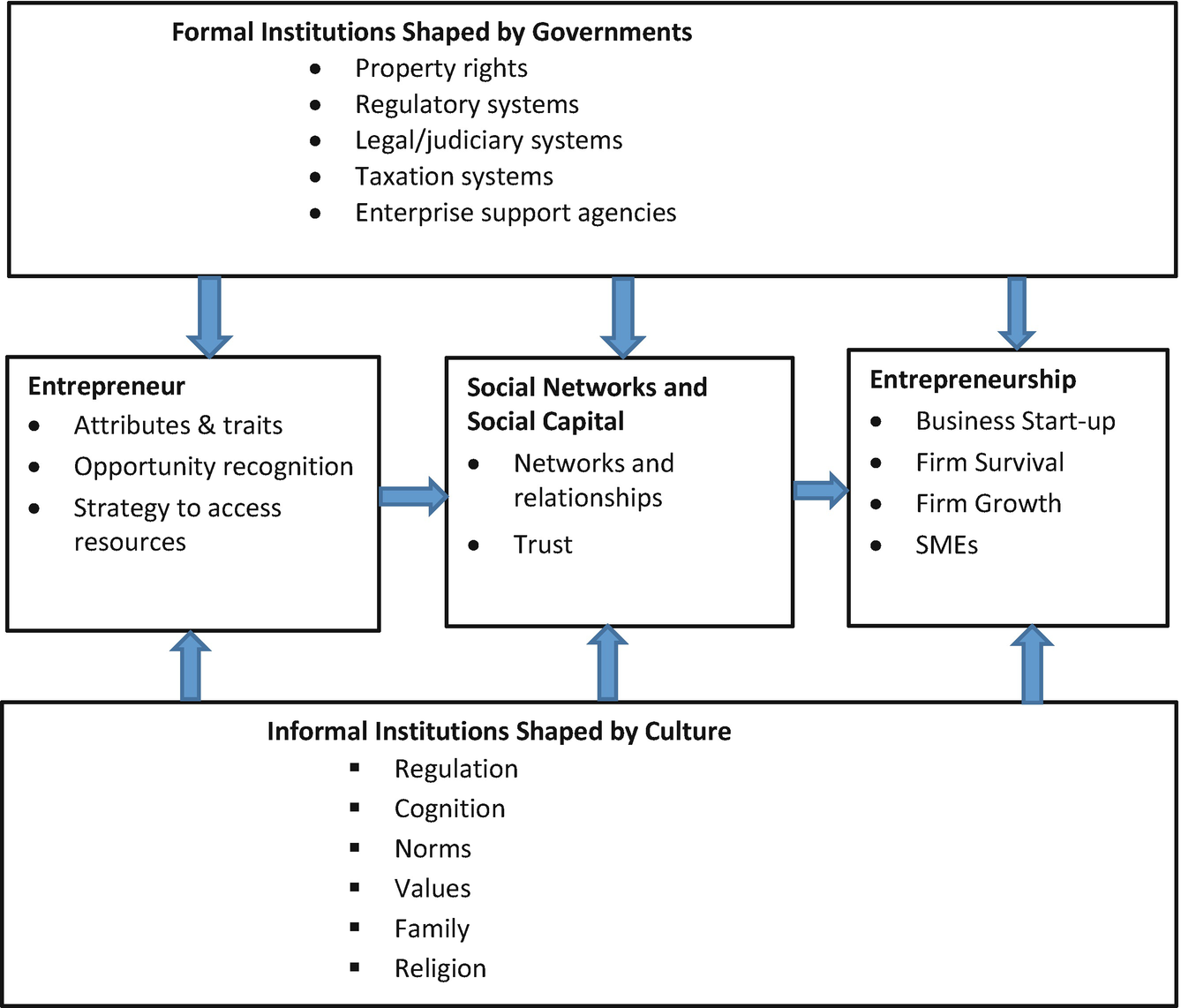

This chapter shows that formal institutions such as legal systems and informal institutions such as culture, cognition, values, attitudes, norms and social networks, social capital, and trust impact entrepreneurship. Specifically, this chapter highlights that entrepreneurship involves the entrepreneur who as an actor draws on institutions to recognise opportunity and formulate strategy by building network relationships and trust to access resources in order to develop and grow a (SME) business.

This chapter contributes to theory, practice, and policy as it offers a balanced approach to the study of entrepreneurship by recognising the role of formal institutions while not underestimating the indigenous cultural institutions, the entrepreneur and social capital, and networking and trust, which are all very important to the entrepreneurial process.

The rest of the chapter is organised in the following manner. The next section (Sect. 2.2) examines the importance and nature of institutions. Section 2.3 looks at formal and informal institutions and how they influence entrepreneurship. Section 2.4 reviews the concepts of social networks and social capital and shows how networks, relationships, and trust enable the entrepreneur to mobilise resources for the entrepreneurial process. Section 2.5 discusses the attributes and role of the entrepreneur and nature and processes of entrepreneurship. Section 2.6 focuses on institutions and entrepreneurial relationships development in Africa. Section 2.7 re-examines institutions and entrepreneurship based on the institutional logics approach and Sect. 2.8 presents the conclusion.

2.2 Institutions: Why Are They Important and What Are They?

Institutions are very important as they influence the nature and level of entrepreneurship and trust in any country or region (North 1990; Welter 2011). The differences in institutions may remain a key factor in the differences in wealth and prosperity across different economies and countries and this is attributed to a number of reasons: institutions spur economic development through limiting costs of transactions, enhancing property rights based on the rule of law, reducing inequalities and oppression by the elites, and enhancing cooperation and social capital. Institutions limit costs by enhancing contracts, contract enforcement, and increased availability of information, all of which in turn reduce risk and uncertainty (Coase 1991). Reliable institutions enhance good returns on investment and property rights (North 1990). Institutions provide trust to entrepreneurs and investors who take risk by investing time and money in ventures in anticipation of the rewards that they can reap in future. These activities require long-term commitments and if entrepreneurs and investors do not have trust in the security of their investments, rewards, and profits, as there is no reliable institutional environment characterised by security and legal systems that prevent criminals or authoritarian rulers from seizing their assets, then they will be unlikely to invest (Estrin et al. 2013). Furthermore, institutions influence the scope of oppression and expropriation of resources by elites by reducing the dominance of powerful elites who dominate economic exchanges and thereby limit economic development (Birdsall et al. 2005). Institutions also enhance networks, social relationships, and social capital by promoting greater interactions, the free flow of information, and the formation of associations, all of which increase the level of trust (Putnam 1993).

Institutions influencing the entrepreneur and entrepreneurship. (Source: Own research)

2.3 Formal Institutions and Entrepreneurship

North (1990) is one of the key contributors to our understanding of institutions. North (1990) emphasises that the types of institutions and their quality influence how the members of a community attain their economic aspirations, entrepreneurship, and the growth of the economy (North 1990). North (1991) defines institutions as the humanly devised constraints that define political, economic and social interaction. Institutions constitute ‘the rules of the game in a society, or more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction’. Institutions evolve incrementally over time and link the present to the past as well as the future, hence the performance of economies is path dependent on the past. According to North (1991) there are formal and informal institutions. Formal institutions include explicit regulations and rules such as constitutions, laws, economic rules, property rights, and contracts, all of which are written down. Formal institutions reduce risks and lower transaction costs for entrepreneurs (Baumol 1990). Institutions ‘affect the performance of the economy by their cost on exchange and performance’ (North 1991), and organisations and entrepreneurs are the players (North 1993). The institutional environment is the set of fundamental political, social, and legal ground rules that establishes the basis for production, exchange, and distribution. This refers to the guidelines that constrain an individual’s behaviour or ‘the rules of the game’.

Government remains the key formal (state) institution in any country and studies suggest that the size of government and its ability to control corruption influence an individual’s decision to become an entrepreneur (Aidis et al. 2012). Government’s implementation of regulatory policy and systems such as taxation and a stable macroeconomic environment all facilitate entrepreneurship (Akimova and Schwodiauer 2005; Sobel 2008). Conversely, regulations that are cumbersome and characterised by red tape increase the transaction costs of starting and managing businesses (North 1990; World Bank 2013), and heavy tax burdens and excessive regulation may drive many micro and small businesses ‘underground’ into the informal economy (Sepulveda and Syrett 2007). Another area where government can facilitate incentives for enterprise development relates to the provision of direct support through private and public enterprise agencies to enhance financial and technical assistance essential for entrepreneurial development (North 1990; Welter and Smallbone 2003).

According to North (1990), informal institutions are the implicit rules such as values, norms, sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct, all of which generally evolve from the society’s culture (North 1990), and constitute many of the rules that shape individual behaviour (Helmke and Lentsky 2003). Informal institutions as unwritten rules that contain the interpretations of formal rules accepted by society and culture also contribute to the enforcement of formal institutions (Welter 2002). Regarding entrepreneurship, informal institutions are important as they shape entrepreneurial opportunities and the acceptable behaviour within a society. Together with formal institutions, they determine transaction and production costs and ultimately the feasibility, legitimacy, and profitability of enterprises. Together, formal and informal institutions provide the incentive structure of an economy which in turn influences the organisations that come into existence, the rewards and incentives that are available, and the direction of economic changes towards decline, stagnation, or growth (Etzioni 1987; North 1991).

Yet, there is a fundamental difference between institutions in advanced and emerging economies (Peng 2003; Smallbone et al. 2014). Predictable and strong governments, regulatory regimes, and legal systems that are taken for granted in developed countries are often lacking in emerging countries (Peng 2003; Amoako and Lyon 2014). However, the economic approach emphasises the importance of formal institutions while paying less attention to informal institutions that play important roles in enhancing entrepreneurship in different contexts (Su et al. 2015). A review of the literature shows that a large number of entrepreneurship studies based on economic theory dominate at the national/state level. Based on such studies, a strong relationship has been established between entrepreneurship and job creation, innovation, and economic growth (e.g. Baumol and Strom 2007). Yet the mainstream economic approaches are underpinned by assumptions of agency and rationality based on which entrepreneurship and the development of trust in entrepreneurial relationships are viewed as rational choices, calculated conscious decisions related to reason (Coleman 1988). However, studies show that entrepreneurs are not always rational actors in their decision making in their search for opportunities or resources (Mitchell et al. 2004).

These concerns are partly addressed by sociological approaches to institutions that focus attention on the embeddedness of actors and how social relationships and cultural institutions influence entrepreneurial agency.

One of the key institutions that is important for entrepreneurship is an efficient judiciary/courts system that ensures compliance with contractual relationships and the absence of rent seeking by actors of the state through bribery and corruption. The case of the UK small claims courts shows how strong formal institutions enable entrepreneurs to seek redress in court without necessarily incurring too much cost. Interestingly, these types of courts are not available in most emerging economies and entrepreneurs have to rely on trust in social networks and indigenous institutions to resolve commercial disputes.

Case Study 2.1 The Small Claims Court and SMEs in the UK

In the UK, entrepreneurs, SMEs, and indeed individuals have the option of going down the small claims track in the circuit court to recover or make claims if the amount is worth £10,000 or less. Yet, there are other options for collecting money including going to the county court or the High Court that may require seeking legal advice. The small claims court enables individuals to make a claim for faulty goods, and faulty services from companies and service providers including builders, dry cleaners, or garages and to recover wages or debts owed. Generally, people do not use solicitors and the time limit for the breach is six years. As part of the process, the complainant must try to resolve the problem before going to court. Complainants can also use third parties to mediate and usually there is a fee for mediation. Defendants are required to reply within 14 days and the amount to be claimed determines the court fees. However, the process may last between a couple of weeks to several months before the payment is received.

2.4 Informal Institutions Shaped by Culture

Sociological institutionalist approaches put much emphasis on society and particularly culture, networks, and relationships. Scott (1995) explains that institutions are multifaceted, durable structures comprising symbolic elements, social activities, and material resources that exhibit stability and yet are subject to both incremental and discontinuous change. Scott (1995) and Kostova (1997) suggest that institutions are comprised of regulatory, normative, and cultural-cognitive forms.

Hence Sociological institutionalist approaches to the study of entrepreneurship posit that entrepreneurs and their firms are embedded in cultural contexts and, as a result, are not atomistic. Culture is defined as the set of shared values and beliefs that (Hofstede 1980) serve as ‘the unwritten book with the rules of the social game that is passed on to newcomers by its members, nesting itself in their minds’ (Hofstede and Hofstede 2005, 36). The focus is that cultural institutions—distinct from political, social, economic, and technological factors—influence the creation of new ventures in a given country (Thornton et al. 2011). Cultural practices reflect particular ethnic, social, economic, ecological, and political complexities in individuals that may lead to differences in attitudes and entrepreneurial behaviour (Wu et al. 2014).

A way to understanding culture at the level of the individual is the framework suggested by Triandis (1972) which proposes that a given culture comprises objective and subjective elements. Objective cultural elements refer to the observable characteristics of culture that are displayed by the individual such as language, religion, and demographic traits. In contrast, subjective elements of culture are not observable outwardly and include the values, beliefs, norms, and underlying assumptions that underpin a culture and the thoughts, feelings, and actions of the members of a particular culture show these elements. The subjective elements of culture refer to the internal cognitive and emotional manifestations of the objective elements of culture.

Chao and Moon (2005) also suggest that the complex ‘mosaic’ of different cultural identities can be categorised into three groups: the demographic (age, gender, ethnicity, and nationality), the geographical (emphasising the role of place and locale), and the associational (related to a range of social groupings such as family, employer, industry, professional group, education, or hobbies). In each of these identities, there are sets of common beliefs and norms that shape entrepreneurial behaviour and mental models (Altinay et al. 2014), and networks and relationships based on sets of meanings, norms, and expectations (Curran et al. 1995), and this will be explored in more detail later in this chapter.

Culture is important in the decision to create new business (Aldrich and Zimmer 1986). Culture may influence entrepreneurial activity through its impact on agency—personal traits, cognition, social norms, and the decision to create a business—and the nature of networks (Welter and Smallbone 2011; Thornton et al. 2011). Furthermore, societies that have positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship and believe that entrepreneurs are well respected and that starting a business is a good career choice impact positively on the development of entrepreneurship. Conversely, societies that are characterised by authoritarian and hierarchical cultures that do not promote, reward, or honour self-made success will not promote entrepreneurship development (GEM 2017).

Hofstede’s (1980) studies offer insights into how national cultures may shape entrepreneurial networks. His framework suggests that power distance, individualism-collectivism, masculinity-femininity, and long-term versus short-term orientation and uncertainty avoidance all affect entrepreneurship and interfirm relationships. According to his framework, power distance demonstrates the level of power between the lowest in society and the most powerful in society, and how people accept these positions. Individualism reflects how people make decisions; a strong, integrated group mentality involving unyielding loyalty and unquestioning authority or, on the other hand, a very individualistic-oriented mentality. Masculinity refers to the extent to which masculine values such as competition, assertiveness, and success are emphasised when compared with feminine values such as quality of life and warm personal relationships. Uncertainty avoidance reflects how society deals with ambiguity and shows how members of a society may either feel comfortable or otherwise in situations that are not structured in a way that is familiar to them. Long-term orientation is characterised by attributes such as thrift and perseverance that are two key values whilst short-term orientated individuals may put the emphasis on respect for tradition and social obligations. Hayton et al. (2002) posit that high individualism, high masculinity, low uncertainty avoidance, and low power distance facilitate entrepreneurship. Shane (1994), however, associates entrepreneurship with high individualism and low uncertainty avoidance. Undoubtedly, Hofstede’s (1980) study offers useful insights into the impact of culture on the development processes of entrepreneurial relationships. However, regarding Africa, critics argue that the evidence is not clear due to what Jackson (2004, 8) calls ‘the lack of cross-cultural insight and model building’. Hofstede’s congruence approach ignores the stark difference between the Western philosophy of life and the African philosophy of life.

2.4.1 Regulatory Institutions

The regulatory aspects involve the setting of rules, monitoring and sanctioning rule breakers (Scott 1995), and offering rewards and punishments that shape future behaviour. The regulatory elements within a particular country are made up of laws, regulations, rules, and government policies that encourage certain behaviours while restricting others (Scott 1995; Veciana and Urbano 2008). These include the political systems, government policies that ensure economic freedom and secure property rights, fair taxation, a fair and balanced legal/judicial system, contract enforcement, and the availability of enterprise-supporting institutions that offer advice, training, and financial support to start-ups (Sobel 2008).

2.4.2 Cognition and Entrepreneurship

‘through socialisation over a period of years within a culture, leading to development of comparatively predictable responses to social situations that are common to a group of people and these shape social and economic relationships’ (Morrison 2000). Socialisation begins in the environment—family, school, work—where a child is raised (Hofstede 1984). This shapes social and economic relationships (Morrison 2000).

Individual cognition remains a key element in the entrepreneurship process as an entrepreneur’s personal attributes may set him or her apart from other people. The cognitive filters allow economic actors to process different information and the propensity to process information (Gibson et al. 2009) and cultural norms and values impact these processes. For example, in economies that regard risk taking and failure as part of the process of innovation, people accept that failure is a necessary part of the entrepreneurial journey (GEM 2017).

2.4.3 Normative Institutions and Entrepreneurship

Scott (1995) posits that normative aspects comprise social norms, values, beliefs, and assumptions about human nature and behaviour that individuals hold and share socially through culture. Norms provide guidelines that shape behaviour and define acceptable and appropriate behaviour in particular situations (Haralambos and Holborn 2000). Norms can be defined as ‘expectations about behaviour that are at least partially shared by a group of decision makers’ (Heide and John 1992, 34) or as informal institutions involving enforcement mechanisms that are built around culture: traditions, customs, moral values, religious beliefs, social conventions, and generally accepted ways of doing things (Zucker 1977; Scott 1995; North 1990). Norms develop over time and may differ across groups and cultures (Fukuyama 1999) through socialisation, particularly during childhood, over a period of years within a culture. This may lead to the development of comparatively predictable responses to social situations that are common to a group of people (Haralambos and Holborn 2000). Formal or informal positive and negative sanctions accompanied by potential rewards for compliance and sanctions for violations help to enforce norms. Thus, norms constitute a major part of social control (Haralambos and Holborn 2000). However, not all norms are desirable since strong reciprocity in a group may lead to hostility or aggression towards non-members. Keefer (2002) refers to ‘clientalism’ and explains that narrow-radius norms that overcome collective action problems within families, social classes, or ethnic groups may have a negative impact on non-members of such groups. For example, when the building of trust and cooperation among groups are segregated based on ethnicity, class or occupation this may lead to negative benefits to the larger society such as discouraging trust with other groups.

Norms and traditions enable or constrain entrepreneurship through, for example, entrepreneurial decision making (Dana 2010), nature, and forms of contracts (Macneil 1980), expectations, reciprocity, cooperation, and trust in personal and interorganisational networks and relationships (Amoako and Matlay 2015; Lyon and Porter 2009). Yet, trust and cooperation among groups if segregated based on ethnicity, class or occupation may discourage trust with other groups and which may in turn lead to negative benefits to society. These issues are explored in more detail in subsequent chapters.

2.4.4 Values and Entrepreneurship

Values provide more general guidelines for conduct while norms provide specific guidelines for behaviour (Haralambos and Holborn 2000). Values have been defined as ‘a type of belief, centrally located in one’s total belief system, about how one ought or ought not to behave, or about some end-state of existence worth or not worth attaining’ (Snow et al. 1996, 124) or as ‘global beliefs about behavioural processes’ (Connor and Becker 1975, 551). Values therefore define what is important and worthwhile, and worth striving for in a society (Haralambos and Holborn 2000). Values underline attitudes—the internal states that express, overtly or covertly, positive or negative evaluative responses to an object, person, or condition (Snow et al. 1996). Norms are expressions of values and both differ from society to society (Haralambos and Holborn 2000). Thornton et al. (2011) suggest that different societies draw on different cultural values to enhance or constrain economic behaviour and entrepreneurship. For example, societal perceptions of failure have many implications for risk taking and the level of entrepreneurial activity in any society (Baumol 1993). This in turn informs how entrepreneurs ascribe attributions for setbacks that may be experienced, and how they change their behaviours as a result. However, culture shapes regulation, cognition, norms and values.

2.4.5 Family and Entrepreneurship

The family remains one of the key institutions that influence entrepreneurship. The literature posits that a family can bring clear values, beliefs, and a focused direction into a business (Burns 2016; Aronoff and Ward 2000). Strong family values shape the performance of business in many ways including decision making, strategic planning, motivating family members and employees to work harder, and constantly challenging the business to renew and enhance conventional thinking and innovation. Furthermore, strong family values can enhance the reputation of the business and promote trust, inspiration, motivation, and commitment among employees (Tokarczyk et al. 2007). Yet, conflicts in family business arise when family and business cultures differ. While, on the one hand, family values emphasise loyalty based on emotion, caring, and sharing, on the other hand, family values can bring a lack of professionalism, nepotism instead of meritocracy, rigidity, and family conflict into the workplace (Schulze et al. 2001; Miller et al. 2009). In contrast, business culture is unemotional, task orientated and based on self-interest; it is outward looking, rewarding performance and penalising a lack of performance (Burns 2016). The African family institution emphasises communalism and is starkly different from Western culture that emphasises individualism and as a result the African family’s impact on entrepreneurship often differs from the Western family’s impact and this is explored in detail in Chaps. 4, 5, and 6.

2.4.6 Religion and Entrepreneurship

Religion is another important institution that influences entrepreneurship and Weber’s (1904) seminal study established that there is a relationship between religious (Christian) values and the development of Western capitalism. Dana (2010) posits that religious values underpin both the environment and the entrepreneurial event. Interestingly, religion is the origin of business concepts such as visions and missions (Vinten 2000). Yet, the relationship between religion and entrepreneurship is complex (Drakopoulou Dodd and Seaman 1998).

At the micro level, religion influences the psychological state of the embedded entrepreneur. Personal belief systems and values influence business (Vinten 2000). In particular, beliefs influence decision making regarding ethics, strategy, leadership styles, and perhaps performance (Vinten 2000; Worden 2005). Religion also shapes the nature of entrepreneurial networks (Drakopoulou Dodd and Gotsis 2007; Dana 2010).

At the macro level, religion shapes national cultures that may in turn influence the behaviour of entrepreneurs. For example, religious values that encourage thrift and productive investment, honesty in economic exchanges, experimentation, and risk taking promote entrepreneurship (Dana 2010). Religion may also shape the social desirability and the propensity to become an entrepreneur (Drakopoulou Dodd and Gotsis 2007). Hence, religion strongly influences believers’ economic activities. Consequently, the level of entrepreneurship between believers from different religions may differ (Zingales 2006).

2.5 Social Networks and Social Capital

Regarding entrepreneurship as a social phenomenon enables us to draw on the concepts of embeddedness to analyse how social networks and social capital influence the entrepreneurial process. The social embeddedness approach is significant because it contests the rational choice view that assumes that the entrepreneur is a hero whose resourcefulness enables him or her to mobilise resources to innovate and create value without recourse to social relations (Chell 2007). Figure 2.1 shows that networks and trust enable the entrepreneur to embark on entrepreneurship.

Granovetter’s (1985) seminal work on embeddedness theorises that economic activities are embedded in networks of social relationships. He argues that embeddedness in networks enables entrepreneurs to perceive opportunity, generate ideas, and mobilise resources to innovate (Shane 2003; Chell 2007). Entrepreneurs draw on their strong ties from family and personal friendships and weak ties from business networks to access resources outside their firms (Granovetter 1985), hence economic relations are sustained by social networks built on kinship, friendship, trust, or goodwill. The network approach reasons that other actors in the entrepreneur’s social and business relations influence their activities (Granovetter 1985). Donckels and Lambrecht (1995) define networks as the organised systems of relationships within an external environment. Networks with key stakeholders such as customers, suppliers, and facilitators, including banks, universities, and trade associations, are essential in providing resources including information, knowledge, expertise, finance, access to markets, and many others that are critical for the survival of start-ups. Networks and relationships may offer resources in overcoming the limitations of institutional weaknesses and of being small, new, or growing ventures (Peng et al. 2008; Wright et al. 2007; Burns 2016). Yet, culture underpins the nature of networks and relationships used by entrepreneurs and organisations based on sets of meanings, norms, and expectations (Curran et al. 1995).

Scholars of social capital focus on the relevance of relationships as a resource for social action (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). Burt (1997) defines social capital as an asset inherent in social relations and networks. Some prior studies have equated specialised networks, norms, and trust with ‘social capital’ (Lyon 2000). Even though originally social capital was seen as relational resources of individuals within their personal ties that may be used for development, studies broadly conceptualise social capital as assets of resources embedded in social relationships (Burt 1992). Understanding social capital is important as the ability of entrepreneurs to recognise opportunity and generate ideas and strategies to mobilise resources for developing businesses and to innovate are shaped by their embeddedness in networks (Chell 2007). The concept of social capital is studied from two different perspectives: structural or rational choice and embeddedness or relational approaches (Anderson 2002). In the rational choice perspective, social capital is concerned with social interactions and refers to the sum of relationships within a social structure. In this approach, social capital refers to a resource that the rational actor uses for self-interested ends. The embeddedness or relational approach emphasises that in addition to individual freedom of action, there is a need for reciprocity and mutuality due to the impact of implicit rules and social mores in embedded contexts. Consequently, the relational approach focuses on the direct relationships of the entrepreneur to others, and the assets of trust and trustworthiness embedded in these relationships (Anderson 2002). This study draws on both rational choice and the relational approach to emphasise the importance of the development of networks, relationships and trust to entrepreneurship in emerging economies such as China and Africa.

Case 2.2 Quanxi: Indigenous Personal Connection That Drives Business in China

The importance of networking and trust in promoting entrepreneurship in emerging economy contexts is exemplified by the Chinese concept of Quanxi, which is an informal personal connection between two individuals based on cultural-specific norms of information sharing, mutual commitment, loyalty, obligation, and reciprocity. Quanxi types differ between family members, friends like classmates, and among business partners who may be strangers. Quanxi development involves identifying with common social identities such as coming from the same hometown, same school, working in the same firm or through a third party with whom either party have a Quanxi. In the context of business, potential partners without a common social identity but having shared values and aspirations can also express an interest in developing a Quanxi. The development of networks is based on familiarisation through the exchange of favours such as gifts and mutual information sharing and reciprocity. There are socio-cultural norms of obligation, affection, feelings, and trust inherent in Quanxi and understanding and adhering to these expectations is critical for the development and maintenance of long-term businesses relationships in China.

Source: Informal interviews with an anonymised Chinese friend.

2.5.1 Institutions and Trust in Entrepreneurship

Trust is important in entrepreneurship (Welter 2005). Apart from facilitating the development of entrepreneurial networks and relationships, trust provides incentives and confidence to invest and do business in any given economy (North 1990; Zucker 1986). Yet, institutions provide the different forms of embeddedness that encourage or discourage trustworthy behaviour and this is important for entrepreneurship and the efficient operation of an economy (Welter and Smallbone 2006; North 1990). State institutions such as the competence or corruption of court officials, the tax system, and other incentives from the institutional environment (Zucker 1986; North 1990) provide the logics and the degree of trust and the ability to trust (Welter 2005).

Nonetheless, as argued throughout this book, in emerging economy contexts, the institutions that facilitate trust development differ from those in developed economies. In developed economies with strong institutions, trust can be based on for example the judicial/legal systems that are used to enforce contracts with individuals and partner firms. However, in emerging economies like India, China and Brazil (see Estrin and Prevezer 2011), and Africa (see Fafchamps 2004; Amoako and Lyon 2014), enterprise support institutions such as judiciary/legal systems are inadequate, and personal relationships underpinned by indigenous, social, cultural institutions rather than state and market institutions enhance trust development (Wu et al. 2014; Amoako and Matlay 2015). In emerging economy contexts, trust serves as a substitute for the incomplete institutional framework (Welter 2002), and trust in informal cultural institutions is important in facilitating entrepreneurship.

Yet, challenges arise where there is cultural difference between two parties due to dissimilar trust expectations and different behavioural rules in conflict situations (Zaheer and Kamal 2011; Ren and Gray 2009). In such cases, cross-cultural relationships can be limited by the inability to draw on common norms and expectations (Dietz et al. 2010). However, currently there is a lack of understanding on how institutional contexts and particularly culture shape specific trust drivers (Li 2016; Bachmann et al. 2015). In the context of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial activities are linked to local contexts and the entrepreneur relies on their embeddedness on local institutions in order to develop trust, in networks and relationships to develop businesses (Baumol and Strom 2007; Welter and Smallbone 2011). This book contributes to bridging this gap by analysing the complex processes through which cultural norms shape the development of trust in entrepreneurial relationships in Africa. Chapter 3 will explore this issue in more detail.

In spite of the immense contributions of institutionalist approaches to the study of entrepreneurship, critics argue that the traditional economic and sociological institutionalist approaches pay more attention to context and little attention to the role of the entrepreneur as an individual. The approach is therefore criticised for over-socialising entrepreneurship (Chell 2007), and for vouching for deterministic approach by emphasising on how institutions constrain or enable entrepreneurship (see Elster 1982; Greenwood et al. 2008). To address these criticisms the next section reviews some of the approaches to entrepreneurship that focuses on agency.

2.6 The Entrepreneur and Entrepreneurship

Central to entrepreneurship are the activities of the individual actor or the entrepreneur who drives the entrepreneurial process. Entrepreneurs who focus their activities on innovation in products and production techniques play a vital role in economic growth, productivity, and increase in social welfare (Baumol and Strom 2007). Schumpeter (1934) is a pioneer academic in entrepreneurship and he argues that the activities of the entrepreneur as an actor creates new firms with entrepreneurial characteristics and these firms displace existing firms that are less innovative resulting in a higher degree of economic growth. Economic development occurs whenever the role of the entrepreneur leads to an increase in income over a specific period. The entrepreneur does new things or does things already done in a new way (innovation).

2.6.1 Attributes of the Entrepreneur

The dramatic achievements of some entrepreneurs lead to notions that entrepreneurs must be different from other people and so there has been keen interest in identifying what makes entrepreneurs creative, innovative, daring, aggressive, optimistic, leaders, dissatisfied with the status quo, and so on (Stevenson and Jarillo 1990; Schumpeter 1934). Psychological theories of entrepreneurship focus on analysing the personal characteristics associated with inclinations of the individual to be an entrepreneur. The key personality traits identified include the need for achievement, an internal locus of control, innovativeness, tolerance of ambiguity, and risk taking. Internal locus of control refers to a belief that the outcomes of our actions are contingent on what we do while external locus of control suggests that the outcomes of our actions are contingent on events outside of our control. Entrepreneurs and business owners exhibit a higher belief that they can control life’s events than other sectors of the population (see Rauch and Frese 2000). Entrepreneurs have a drive to achieve and excel and Johnson (1990) found that there is a relationship between achievement motivation and the decision to become an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurs have a tolerance of ambiguity and that describes how individuals perceive and process information about ambiguous situations when faced with unfamiliar, complex issues (Mohar et al. 2007). However, the personality trait model is criticised for overemphasising rationality and portraying the entrepreneur as a rational, heroic individual while ignoring the role of institutions and therefore undersocialising entrepreneurship (Busenitz and Barney 1997).

2.6.2 Opportunity Recognition

The entrepreneur is the actor who recognises opportunity in the entrepreneurial process. Shane (2003) explains that the entrepreneurial process involves, first, the ability to perceive new opportunities that cannot be proved during the moment when action is taken. In this book, the author defines opportunity as a chance to exploit a given situation that may lead to starting or growing a business. Drucker (1985) is a prominent proponent of the opportunity-based theory of entrepreneurship and he disagrees with Schumpeter’s (1934) assertions that entrepreneurial activities cause change. Instead, Drucker (1985) argues that entrepreneurs search for and exploit change as an opportunity. In this theory, the entrepreneur focuses on possibilities rather than problems created by change. This approach reaffirms Kirzner’s (1997) theory of entrepreneurial alertness. The opportunities result from changes in the environment but are not out there as objective entities for everyone to see (Veciana and Urbano 2008). The discovery of business opportunities involves alertness and boldness and the entrepreneur who has the necessary idiosyncratic knowledge discovers the opportunities (Kirzner 1973; Veciana and Urbano 2008). Kirzner (1997) reiterates that an entrepreneur is one who perceives profit opportunities and initiates action to fill currently unsatisfied needs or to improve inefficiencies. To act means to discover opportunity during uncertainty. However, opportunity recognition is just the beginning and the entrepreneur needs to formulate a strategy to mobilise the necessary resources in order to translate idea into a business. In this book, the author draws on Schumpeter, Drucker and Kirzner’s theories to argue that entrepreneurs’ risk taking, boldness, and alertness to profit opportunities, enable them to build networks and trust-based relationships based on strategy to facilitate access to critical resources.

2.6.3 Strategy to Access Resources

Entrepreneurship draws on the resources based view (RBV) to theorise that availability and mobilisation of resources are critical for the entrepreneurial process (Barney 1991). Entrepreneurs utilise different strategies to mobilise resources needed to exploit opportunities for their firms. Entrepreneurial resources include ideas, motivation, information, capital, access to markets, skills and training, and the goodwill inherent in bureaucracy (Kristiansen 2004). The resources affect the start-up, survival, and growth of the firm. There are three main strategies used by entrepreneurs to access resources. First, entrepreneurs often rely on their own resources such as skills, and capital to finance their ventures. Second, entrepreneurs apply combinations of available, undervalued, and less utilised resources free or cheaply to exploit opportunities (Baker and Nelson 2005). Finally, entrepreneurs utilise their personal and business networks to access resources outside their firms (Granovetter 1985).

Consequently, critics of the agency perspective argue that by focusing on entrepreneurs as heroes and ignoring the context, important factors such as trust, networks, and relationships that are critically important for mobilising resources for the entrepreneurial process may be ignored (see Chell 2007).

In summary, this section shows that the entrepreneur’s attributes and traits, alertness, opportunity recognition and strategy to access resources lead to entrepreneurship. Yet, the institutional environment and social capital, networks, and relationships and trust all mediate the process. The next sub-section reviews the literature on entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is vital for economic growth as it leads to new businesses, innovation, and job creation (Birch 1979; GEM 2016). Entrepreneurship is regarded as the fourth factor of production after land, labour, and capital (Acs 2006). The word entrepreneurship originates from the archaic French word ‘entreprennoure’ which originally referred to a manufacturer, a master builder, or a person who takes up a project (Herbert and Link 2006). Interestingly, while there is consensus on the role of entrepreneurship in economic development, there is no agreement on the definition of entrepreneurship (Kobia and Sikalieh 2010).

Yet, there are some well-known definitions. For example, Shane and Venkataraman (2000) define entrepreneurship as the discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities. Shane (2003) later defines entrepreneurship as the ability to mobilise entrepreneurial ideas and resources to develop businesses within a given context. Drawing on these two definitions, in this book, the author defines entrepreneurship as the ability to recognise and evaluate opportunity and mobilise resources to establish and grow a business in a given context. This definition integrates entrepreneurial action with context and the need to mobilise resources and grow a business.

Entrepreneurship remains complex because the term involves not only the process of starting up a business entity but also entrepreneurial behaviour, development, and growth or expansion of a business entity. Nonetheless, there is an important distinction between independent early-stage entrepreneurial activity by individuals starting and managing a business for their own account and risk, and the pursuit of opportunity within existing organisations known as intrapreneurship. Entrepreneurship therefore is a multidimensional concept that involves many different actors and several levels of analysis and, in this book, the author draws on Schumpeter, Drucker and Kirzner’s theories to argue that entrepreneurs’ risk taking, boldness, and alertness to profit opportunities, enable them to build networks and trust-based relationships that facilitate access to critical resources.

Schumpeter’s (1934) theory regards entrepreneurship as a force of creative destruction through which new firms with entrepreneurial characteristics displace existing firms that are less innovative giving rise to a higher degree of economic growth (Katsikis and Kyrgidou 2008). Schumpeter was the first scholar to highlight the close relationship between entrepreneurship and innovation, and his concept of creative destruction explains how innovations disrupt technologies, sectors, and industries leading to economic growth. Entrepreneurship is widely regarded as a positive force in market economies (Saunders et al. 2010). Schumpeter (1934) therefore links innovation to the entrepreneur and differentiates between five main types of innovation: introducing a good; introducing a new method of production; opening a new market; conquering a new source of raw materials; and reorganising an industry in a new way. However, Schumpeter’s (1934) theory has been criticised due to assumptions of rationality. Baumol (1990) also contends that the main limitation of Schumpeter’s theory is its silence on how government policy influences entrepreneurship. This is essential since institutional environments affect the structure of payoffs and the rules of the game (North 1990).

Entrepreneurship though has a dark side including entrepreneurial failure and other destructive impacts. Entrepreneurial failure is an integral part of the entrepreneurship process, yet there is no clear meaning of what constitutes entrepreneurial failure. Failure can be subjective or objective and even though academics rarely separate failure of the business and failure of the entrepreneur, they are not the same. This is because failure of a business may not necessarily mean failure of the entrepreneur, as an entrepreneur whose firm has failed may move on and establish a successful business. Conversely an entrepreneur may fail and yet the business may be taken over and be successful under a different entrepreneur (see Jenkins and McKelvie 2016; Saravasthy et al. 2013). Interestingly, prior studies have focused more on external logics that cause business failure rather than on the failure of the entrepreneur and the impact on the individual entrepreneur. Entrepreneurial failure can have very serious consequences on the entrepreneur including negative emotions and grief (Shepherd 2003) accruing from personal loss and at times can strain relationships. Other negative impacts include financial loss, loss of skills, loss of social capital, stigmatisation, and devaluation of entrepreneurs (Cardon et al. 2011),

Furthermore, entrepreneurship can be unproductive and in some cases destructive (Baumol 1990). Entrepreneurs can choose between productive ventures that create economic and social value and unproductive ventures in which rent-seeking behaviour reduces the incentive to engage in productive economic activities. Rent seeking can also involve lobbying, litigation, tax avoidance and evasion, monopoly, stealing and raiding productive inputs, as well as shadow venture activities such as drug dealing, prostitution, and corruption. Rent seeking can also lead to destructive activities based on the illegalities and damaging effects of entrepreneurial activities on society and on the environment.

The destructive nature of entrepreneurship is particularly manifest in emerging economies such as Africa due to the existence of weak formal institutions that cannot often enforce the law. For example, activities of some oil and mining companies are causing mass deforestation of tropical forests and the contamination of river bodies across Africa, although they operate legally. There are other forms of destructive entrepreneurship and these take the form of criminal and illegal activities across the continent even though there are regulations that seek to prevent these destructive activities.

Given the potential unproductive and destructive nature of entrepreneurship, recently there has been an upsurge in social entrepreneurship that seeks to enable businesses to achieve the triple bottom line (TBL) by creating economic, social, and environmental value. Increasingly, social entrepreneurs are using entrepreneurial problem solving, creativity, and innovation in addressing the social, economic, and environmental problems of society and creating social and environmental value while remaining profitable to ensure sustainability (Doherty et al. 2014). Social entrepreneurship is increasingly playing a vital role in the transformation of economies and society in Africa and globally.

In recent years, there has been a tendency to regard entrepreneurship as a broader phenomenon that manifests itself in entrepreneurial mindsets, attitudes, and behaviour in non-economic arenas (Cieślik 2017). For example, in the areas of higher education, health, public administration, and the voluntary/charity sectors and politics, entrepreneurship is about the deployment of entrepreneurial skills and creative thinking to solve endemic problems.

In spite of the emphasis on entrepreneurship as an activity carried out mainly by individual entrepreneurs, recently there has been an interest in ‘teampreneurship’ that involves individual entrepreneurs working and learning in teams. The model is developed and championed by Team Academy (Tiimiakatemia), a Finnish entrepreneurship education programme that started about 20 years ago. The core philosophy of the programme is that students as ‘teampreneurs’ learn better via self-determined learning through which teams establish a business (see Lehtonen 2013).

2.6.4 Entrepreneurship and SMEs

Apart from the institutional environment and the competencies of the entrepreneur or teampreneur, the organisational arrangements of the firm are also important for entrepreneurial success. However, entrepreneurship exists in both large and small firms yet, in this book, the emphasis is on SMEs. Within SMEs, there is a non-separation of entrepreneurship and the small firm (Hill 2001). Entrepreneurial processes may often result in a business start-up in the form of a small business or may take place in an existing small firm and the entrepreneur will own, manage and grow the small firm in the midst of uncertainty and risk. However, it is important to state that not all SME owners/managers are entrepreneurs (Drucker 1985). In this book, the owner/managers who are interviewed are regarded as entrepreneurs given their zeal in risk taking regarding building trust-based relationships to grow their SMEs.

The literature identifies the main reasons for the interest in the SME sector shown by researchers and governments. SMEs play a key role in the global economy (Franco et al. 2014) and are regarded as the backbone of many economies as they contribute to job creation and act as suppliers of goods and services for larger firms (Walsh and Lipinski 2009), as well as promoting innovation, economic stability, and development (Cunningham 2011). The ILO (2000) demonstrates that the SME sector contributes significantly to national development goals in diverse ways. These include linkages through horizontal and vertical integration, equitable growth across regions, mobilisation of savings and financial resources internally for productive enterprises, and as a seedbed for medium and large firms. Consequently, the International Labour Organization (ILO) has recognised SMEs as a mechanism for new employment opportunities.

SMEs affect local economies significantly. Their impact on local economies emanates from their utilisation of resources, information, and markets in their immediate environment (Romanelli and Bird Schoonhoven 2001). Furthermore, the venturing process draws ideas for new products and services, and new sources of customer demands for existing products, from the immediate environment (Aldrich and Wiedenmayer 1993). Informal networks enable entrepreneurs to raise finance (Aldrich 1999) and the provision of business support and advice may originate from the immediate environment (Bennet and Smith 2002). This dependence on the local environment has led academics to view entrepreneurship as contextualised and therefore embedded (Jack and Anderson 2002; Granovetter 1985).

Interestingly, there is no uniformly acceptable definition of SMEs (Burns 2016). No single definition could cover all the divergent industries, therefore academics and policy makers use different qualitative and quantitative criteria to define SMEs (Bolton Report 1971). There is also a lack of clarity about firms regarded as SMEs as different countries adopt different measures. For example, in the United States, an SME refers to a firm employing not more than 500 employees (Burns 2016); in the European Union, SMEs employ fewer than 250 people (EU 1996). Similarly, definitions vary among African countries. For example, an SME describes a firm employing not more than 20 employees in Tanzania, 50 in Malawi, and 100 in Ghana. Therefore, critics argue that the many definitions cause practical problems (Burns 2016). Particularly, the lack of clarity renders SME policy formulation difficult. Therefore, to enhance simplicity and practical application in this book, the author adopts the definition from the Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development in Ghana that regards firms employing less than 100 people as SMEs. This is because the data for the author’s PhD was collected from Ghana based on this definition.

SMEs differ from large firms. Typically, they use simple systems and procedures that facilitate flexibility, immediate feedback, a short decision-making chain, better understanding, and quicker response to customer needs than larger organisations (Singh and Garg 2008). One of the distinctive features of SMEs is the dominant role of the entrepreneur in the decision-making process of the firm (Carson and Gilmore 2000). In spite of these advantages, SMEs are constrained when compared with large firms. SMEs have severe limitations of resources and lack management competencies (Fillis 2002). They lack resources—time, cash, and technology—and therefore are characterised by a short-term planning perspective, are likely to operate in a single market, and are over-reliant on a small number of customers (Barry and Milner 2002; Burns 2016). Due to lack of cash, SMEs have difficulties in achieving economies of scale in the purchase of inputs, such as equipment, raw materials, finance, and consulting services (Buckley 1997).

Given the constraints faced by smaller enterprises, scholars posit that the development of networks, relationships, and cooperation may mitigate the liabilities associated with being small (Wright et al. 2007; Burns 2016). Thus, social networks and social capital are hugely important to SMEs.

The next two sections re-examine the debates on institutions, the entrepreneur and entrepreneurship in Africa and attempt to marry the two perspectives by using the institutional logics perspective.

2.7 Institutions and Entrepreneurial Relationship Development in Africa

Reports and studies suggest that African countries are characterised by weak and unsupportive formal institutional environments (The Economist 2016; Bruton et al. 2010). The poor institutional environmental factors including political instability, poor infrastructure, poor macroenvironments, lack of access to capital and corruption impede growth and internationalisation of African businesses (Ibeh et al. 2012). Yet recently, there have been improvements in formal institutional environments in a number of African countries including Ghana, Nigeria, Angola, Rwanda, Tanzania, Zambia, and Ethiopia and these and many other countries in the continent offer opportunities to entrepreneurs and investors. Yet African governments can do more to stimulate entrepreneurship. Sriram and Mersha (2010) emphasise that in addition to the role of entrepreneurs, government policy can stimulate entrepreneurship development in Africa.

Traditionally, Africa’s business opportunities have been linked to the trade and export of raw and non-value-added commodities such as gold, timber, oil, coal, tea, coffee, leather, palm oil, and many others which were mostly exploited by national governments and multinationals. However, currently Africa offers countless business opportunities in non-traditional sectors such as agriculture, food processing, banking, consumer goods, infrastructure, and telecommunications (Accenture 2010). There are also other emerging areas including transforming local waste into greener alternatives, renewable energy, real estate development, fashion, start-up funding, healthcare, education, creative industries, and so on. African entrepreneurs and investors can focus on these opportunities to stimulate the economy instead of a reliance on the traditional lifestyle businesses that constitute the majority of SMEs in the continent.

Not surprisingly, Africa is now home to many successful and well-known entrepreneurs including Aliko Dangote (manufacturing, Nigeria), Mo Ibrahim (telecommunication, Sudan), Apostle Kojo Sarfo (motor vehicles, Ghana) and Elon Musk (technology, South Africa). While these entrepreneurs are operating larger businesses, the continent is teeming with countless entrepreneurs owning and managing innovative SMEs that are transforming the enterprise and economic landscape in Africa and beyond.

Prior studies on entrepreneurship in Africa found that successful African entrepreneurs tend to be male, middle-aged, married with a number of children, and on average more educated than the general population (Kiggundu 2002). Nevertheless, other studies report higher numbers of female entrepreneurial involvement in Africa (e.g. Mead and Liedholm 1998; Nziku 2012) and current entrepreneurial profiles range from young, old, males and females, highly educated to illiterates, all with a quest and passion to make a difference even though the vast majority operate in lifestyle businesses that are less innovative.

Entrepreneurs and their SMEs operate in many sectors, including waste and sanitation, information and communication technology, health and social care, agriculture, agro processing, manufacturing, communications, fashion, tourism, hospitality, financial services, consultancy, and so on. These enterprises continue to make significant contributions to social, economic, technological, and environmental development in spite of the prevailing institutional voids.

While previous studies found government attitudes and societal values in some African countries such as Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Ethiopia to be unsupportive of entrepreneurship due to the underlying socialist values of governments and capitalist values of entrepreneurship (see Buame 1996; Kallon 1990), times have changed and currently there are positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship in African economies (Saheed and Kavoos 2016). For example, since the year 2000, there have been a number of initiatives to facilitate entrepreneurship in Ghana. Furthermore, in 2017 the Ghanaian government launched the Ministry of Business Development whose flagship programme is the National Entrepreneurship and Innovation Plan (NEIP) with an initial seed capital of $10 million which will be scaled up to $100 million through private sector development partners (GoG 2017). Similarly, in Sierra Leone, the government’s Agenda for Change (2008–2012) and Agenda for Prosperity (2013–2017), among others, aim to provide business development and career advice and guidance to its youth (UNDP 2018).

While improvements in the formal institutional environment may partly explain why entrepreneurship is vibrant in Africa (see World Economic Forum 2018), it is also obvious that informal institutions such as cultural norms, changing attitudes, personal networks, and trade associations enable entrepreneurs owning and managing SMEs to develop trust in order to establish and grow business ventures. Yet, these institutions have received very little attention from researchers (Amoako and Lyon 2014; Amoako and Matlay 2015; Jackson et al. 2008). Not surprisingly, there is very little understanding about how African entrepreneurs develop trust in networks and ties to enable access to resources for undertaking entrepreneurship in the context of weak state institutions.

2.8 Re-examining Institutions and Entrepreneurship

Given the context-based rationality of institutions, critics have argued for further development of institutional theory to take into account cognitive foundations of entrepreneurial behaviour (Welter 2002). In response, notions of institutional logics that reject both macrostructural theories and individualistic, rational choice perspectives are proposed as a more balanced approach (Thornton et al. 2012; Friedland and Alford 1991). Thornton et al. (2012: 2) define institutional logics as the ‘socially constructed, historical patterns of cultural symbols and material practices, including assumptions, values, and beliefs by which individuals and organisations provide meaning to their daily activity, organize time and space and reproduce their lives and experiences’. The institutional logics perspective also assumes that institutions are historically contingent (Friedland and Alford 1991). Thornton et al. (2012) suggest that Western societies are based on seven core societal institutions and their logics: family, religion, state, market, profession, corporation, and community.

The author draws from Thornton et al.’s (2012) institutional orders and their logics to categorise institutional orders whose logics influence trust development in Africa into two main groups, namely logics of state and market institutions, and logics of indigenous cultural institutions. While the logics of state and market institutions focus on state institutions, particularly the legal/court systems and enterprise facilitating bodies, the logics of indigenous cultural institutions of African societies include traditional judicial systems, trade associations, language, family/kinship, religion, gift giving, and punctuality.

The institutional logic approach enables the author to highlight how cultural dimensions both enable and constrain social action (Thornton and Ocasio 2008) and how actors use logics to interpret and make sense of the world while the logics offer resources for relationship building, identity construction, and decision making. Based on this perspective, entrepreneurs as organisational actors make strategic choices to shift the rules and the norms that influence organisational choice, behaviour, and the distribution of resources (Vickers et al. 2017; Thornton et al. 2012). Thus, the embedded actor does not necessarily succumb to institutional structures but instead, acts in ways to counter the constraints and taken-for-granted assumptions prescribed by institutions; hence this approach presents a balanced view between institutions and entrepreneurial action (Vickers et al. 2017).

Furthermore, the author argues that contrary to current assumptions that Africa’s weak institutions make the continent unattractive for entrepreneurship, the development of networks, relationships, and trust enable entrepreneurs to establish and manage businesses successfully just as in China and other emerging economies where investors are keen to invest.

2.9 Conclusion

This chapter shows that institutions are very important for entrepreneurship and economic development in any country. Yet, it also highlights that while state and market institutions have an influence on entrepreneurship, cultural institutions such as cognition, norms, values, attitudes and social networks and trust also influence the entrepreneurial process. This chapter shows further that entrepreneurship involves the entrepreneur who as an actor draws on institutions to recognise opportunity, formulate strategy (Thornton et al. 2012), and develop networks, relationships, and trust to access resources.

This chapter shows that both formal and informal institutions are important for entrepreneurship and economic development. In mature market economies, strong state and market institutions enhance entrepreneurship. Yet, socio-cultural institutions also shape entrepreneurial behaviour even though the reports and literature do not often highlight them. Culture plays an important role in entrepreneurship due to its impact on cognition—norms, values, beliefs—and trust development in entrepreneurial networking. While current reports and assumptions about entrepreneurship emphasise the role of state and market institutions, in emerging countries where these institutions are weak, cultural institutions and trust enable entrepreneurs to embark on entrepreneurship.

This chapter also sheds light on the role of the entrepreneur. The entrepreneurial process starts with opportunity recognition and the formulation of a strategy by the entrepreneur to access resources from him or herself or from networks, relationships with friends and acquaintances, or family/kinship. By including the entrepreneur in Fig. 2.1, this chapter shows that both institutions and the entrepreneur, as an actor, play a role in the entrepreneurial process. It also shows that networks, relationships, and trust enable the entrepreneur to access resources. The framework is particularly useful in analysing entrepreneurship in emerging economy contexts where, in the absence of strong state and market institutions, entrepreneurs rely on social and business networks, and relationships that are based on trust in order to do business (see Wu et al. 2014; Amoako and Lyon 2014). This may explain why even though there are weak formal institutions in emerging economies such as China, India, and Africa, entrepreneurship is vibrant. Yet, there is very little understanding of how culturally specific institutions influence entrepreneurial activity in Africa and this gap will be addressed in Chap. 4.

This chapter contributes to knowledge by showing that entrepreneurship involves the role of state and market institutions, cultural institutions and the entrepreneur who as an actor develops networks, relationships, and trust in order to access resources to develop or grow businesses. By so doing, this chapter helps to avoid the under- or oversocialisation of entrepreneurship.