3.1 Introduction

Trust serves as the glue that binds people together and it is critical in every human relationship ranging from spouses, families, friends, sports teams, and political parties to business. Lack of trust leads to suspicion and lack of collaboration and often lack of cooperation. In the context of business, trust offers many advantages such as binding all key stakeholders to the business and enabling long-term relationships, access to resources, and growth (Welter 2012; Burns 2016). Nonetheless, trust involves risks, uncertainty, and vulnerability associated with whether the other party has the intention and the will to act as expected (Mayer et al. 1995; Rousseau et al. 1998; Möllering 2006).

The main challenge in the study of trust relates to its complex nature and a review of the literature reveals that there is lack of consensus among researchers on a number of issues such as definitions, the number of dimensions, operationalisations and methodologies, its relationship with contextual factors such as networks and relationships, contracts, power and institutions. The lack of consensus results from divergent assumptions originating from the diverse disciplines involved in the study of trust. For example, psychology (e.g. Rotter 1971) traditionally approaches the study of trust by focusing on internal cognitions of trustors and trustees, in terms of their attributes, but pays less attention to the role of the environment or contexts. Most economists, on the other hand, regard trust as rational and calculative with actors mostly focused on their own benefits; as a result, economist underestimate the context or institutions (e.g. Gambetta 1988; Williamson 1993). Sociologists and old institutional economists suggest rather that sometimes actors rely on institutions that guide individuals and affect or shape their motivation to trust without personal knowledge of the individual (Zucker 1986). This approach suggests that trust is routinised and embedded in social relations (e.g. Granovetter 1985) or in institutions (Zucker 1986) while underestimating the role of the trustor, trustee, and the power relations that may lead to trust asymmetry and greater vulnerability of one of the parties (Bachmann 2001). Process theorists, on the other hand, suggest that in situations where actors do not have prior interactions and cannot rely on institutions, trust development becomes a reflexive process that is learned through interactions based on mutual experience, knowledge, and rules that develop over time (Möllering 2006). Lewicki and Bunker (1996, 135) compare these fragmented approaches as being similar to blind men, each one ‘describing his own small piece of the elephant’. There is therefore a major gap in the literature for a holistic approach that examines the trustor, trustee, context, and their relationship (Li 2016; Chang et al. 2016).

This chapter aims to review the literature to develop a conceptual framework that presents a holistic view of trust by examining the entrepreneur as trustor, his or her exchange partner as trustee, the external cultural norms that shape trust development, and their interactions in relationships. The analysis and discussions aim to marry the different approaches to the study of trust: (1) as a rational choice, (2) as routine and taken for granted, and (3) as a reflexive process.

- RQ1

What is trust?

- RQ2

How is trust developed?

- RQ3

How is trust violated and repaired in interorganisational relationships?

The author provides answers to these questions by reviewing the literature on trust theory to offer an understanding of trust, how it is developed, violated, and repaired. The chapter presents a holistic view of trust that incorporates the trustor, trustee, their relationships, interactions, and the institutions that shape trust development and the outcomes of trust.

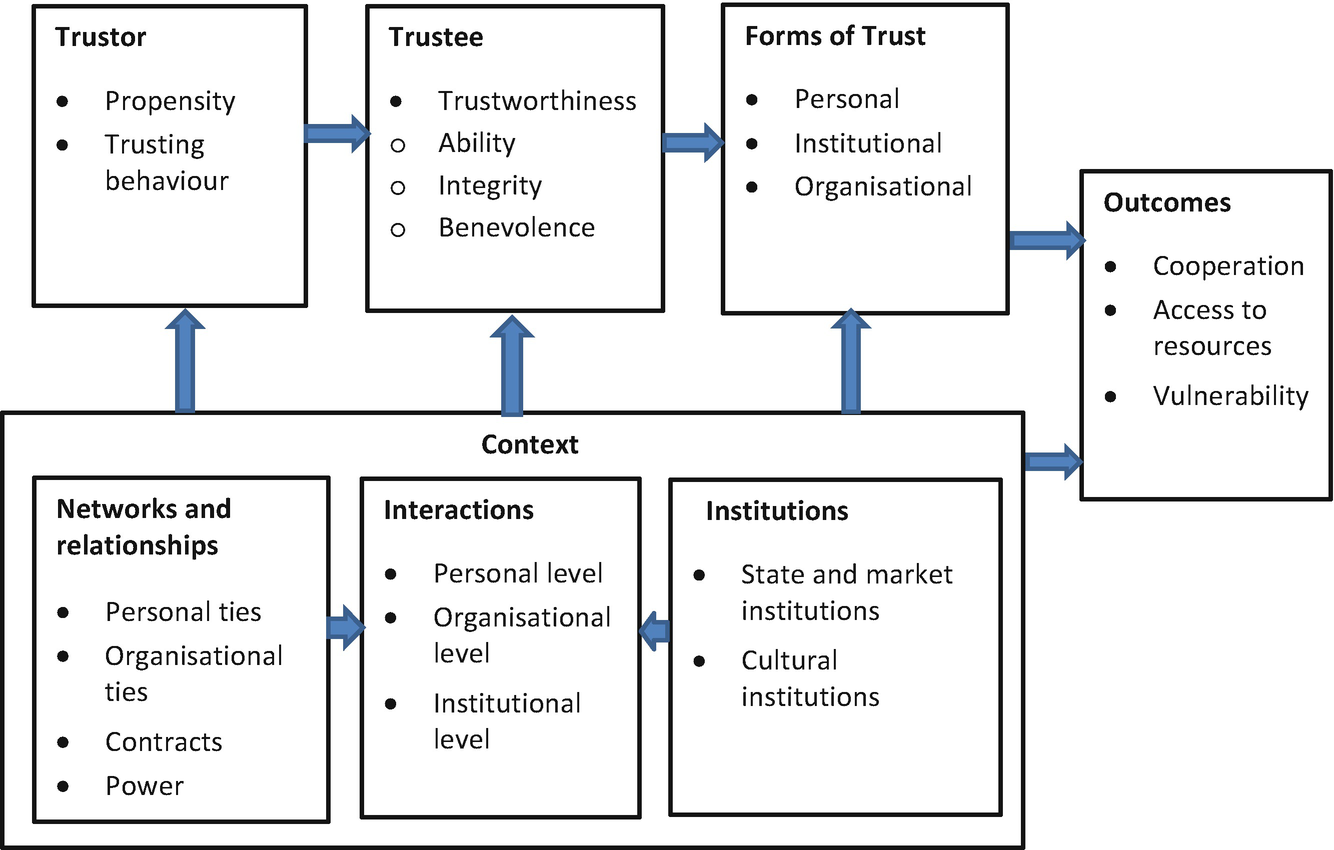

Interorganisational trust in Entrepreneurial Relationships. (Source: Own research)

This chapter contributes to the literature in two main ways. It reviews the literature and highlights the current debates and gaps in interorganisational trust research in relation to entrepreneurship and small business management. Second, it presents a theoretical framework that offers a holistic view of trust development involving the trustor, trustee, institutions, relationships and interactions, and outcomes of trust.

The rest of this chapter is structured as follows. Section 3.2 answers the question of what constitutes trust by presenting the different definitions of trust based on different theoretical perspectives. Section 3.3 presents a model (Fig. 3.1) of interorganisational trust development in detail. Based on the framework, the literature review examines the roles of: contextual factors namely: networks and relationships, contracts, power interactions and institutions in trust development. This section also examines the role of the trustor and the trustee and ends by discussing trust outcomes. Section 3.4 reviews the literature on trust violations; Sect. 3.5 examines trust repairs and Sect. 3.6 concludes the chapter.

3.2 Trust: What Is It?

Trust has been widely studied by different disciplines. Yet, it remains a complex concept because it is multilevel, multidimensional, and plays many causal roles. Not surprisingly, it does not yet have an agreed definition as different disciplines have propounded different definitions, and even studies that use similar theoretical approaches have not necessarily used similar definitions (Rousseau et al. 1998). There is no single definition and as at 2014 there were over 121 trust definitions (Seppanen et al. 2007; Walterbusch et al. 2014) and the number continues to rise.

3.2.1 Definitions: Trust

Definitions of trust that draw on rational choice approaches focus more on the actor and rationality. For example, Mayer et al. (1995, 715) define trust as: ‘the willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control the other party’. Mayer et al. (1995) focus on the actor while paying less attention to the context. Similarly, in economics, Gambetta (1988, 217) is widely cited for his definition of trust as ‘a particular level of the subjective probability with which an actor assesses that another actor or a group of actors will perform a particular action, both before he can monitor such action (or independently of his capacity ever to be able to monitor it), in a context in which it affects action’. Gambetta (1988) regards trust as a rational decision. However, one can argue that the rational choice approaches pay less attention to the norms that may underpin how different people see the same situation. Zucker (1986, 54) takes a sociological view and states that trust is ‘a set of expectations shared by all those involved in an exchange’. This relates to both the idea of trust as a state of mind developed by an individual through interaction with others and trust as a reliance based on institutional safeguards (Bachmann and Inkpen 2011). Rousseau et al. (1998, 395) also combine the cognitive rational and sociological views, and define trust as ‘a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the behaviour of another’. In contrast Möllering (2006) focuses on the process view in his definition of trust and emphasises uncertainty, risks, and vulnerability. Möllering (2006) defines trust as ‘a reflexive process of building on reason, routine and reflexivity, suspending irreducible social vulnerability and uncertainty as if they were favourably resolved, and maintaining a state of favourable expectation towards the actions and intentions of more or less specific others’.

In this book, the author draws on all the above definitions to formulate a working definition of trust as ‘a set of positive expectations that is shared by parties in an exchange that things and people will not fail them in spite of the possibility of being let down’. Based on this working definition, the author argues that entrepreneurs’ trust development is based on their belief in the trustworthiness of the trustee based on interactions and accepted norms within specific contexts. This definition also recognises that trust is fraught with risks and vulnerability. Hence, within entrepreneurial relationships, trust calls for boldness and alertness (Schumpeter 1934, 1942; Kirzner 1979).

3.2.2 Trust: Rational, Routinised, or Reflexive and Process-Based?

Economic approaches draw on rational choice theory in the study of trust (Becker 1976). Rational choice theory assumes that decision makers are highly intelligent with clear objectives. Rational actors therefore are able to calculate and evaluate available alternatives and choose the best solution that optimises the decision maker’s utilities (Misztal 1996). The rational choice paradigm regards trust as based on reason, and is conscious and calculated (e.g. Gambetta 1988; Williamson 1993). Williamson (1993) offers an economic calculative perspective of trust based on control, reciprocity, and conditional cooperation. According to Williamson (1993), the term calculative trust refers to the use of wisdom, rationality, and an economic calculative approach to trust and cooperation. Gambetta (1988) describes trust based on calculation as: some actor A, trusts some actor B when A calculates that the probability of B performing an action that is beneficial, or at least not detrimental, to A is high enough for A to consider engaging in some form of cooperation with B. Calculative trust is based on past experiences and trust development is based on the outcomes of risk taking or experience, equity preservation, and inter-firm adaptations (Williamson 1993). The approach suggests that actors are opportunistic, self-interested, and mostly focused on their own benefits. Hence, the rational choice approach has been criticised for overemphasising the role of the actor in placing trust (Zucker 1986; Möllering 2006).

Sociologists however disagree with economists on the calculative approach due to the habituation of trust based on norms and codes of conduct (Granovetter 1985; Zucker 1986). The critics argue that if trust is a matter of pay-off between trustor and trustee, then the trustee should rationally terminate the trust if there is no immediate pay-off. However, evidence suggests otherwise and Möllering (2006) explains that actors may sometimes be irrational and deliberately act in ways that enhances the utility of others. Even though irrational action may not be the dominant approach in social action, rational choice cannot explain all aspects of social action and that social norms, reciprocity, and cooperation may underpin trust (Elster 1989). Furthermore, actors may rely on systems of regulation, which guide individuals, shape their motivation and behaviour, and affect their behaviour to place trust without personal knowledge of the individual (Simmel 1950). However, critics argue that sociological approaches put too much emphasis on routines and the roles of institutions while marginalising agency, i.e. the trustor and trustee. Obviously, the role of the actor (trustor and trustee) is important since actors need to trust institutions before the institutions become a source of trust between actors (Möllering 2006). Calculation, routines, and cultural norms shape trust development: therefore, trust can be calculative but also routinised.

Apart from the rational and routine approaches, process theorists argue that trust is a reflexive process that is dependent on ongoing interactions between actors (Möllering 2006). In situations where actors do not have prior interactions and cannot rely on institutions, trust development becomes a process that is learned through interactions based on mutual experience, knowledge, and rules that develop over time. Even though such interactions may start relatively blindly or accidentally, these interactions may become self-reinforcing in a process of reflexive familiarisation and structuration (Möllering 2006, 80).

Regarding trust development in entrepreneurship, one can argue that entrepreneurs are not always rational actors in their decision making and in their search for opportunities or resources (Baron 1998). Academics have demonstrated that under certain circumstances heuristics and biases in strategic decision making influence entrepreneurs to develop and use non-rational modes of thinking (Busenitz and Barney 1997). Under certain conditions, entrepreneurs may also trust based on institutions when they do not have prior knowledge (Zucker 1986) whilst in other conditions they may have to develop trust based on their interactions when they do not have prior knowledge and cannot also rely on institutions (Möllering 2006). Figure 3.1 presents a model that shows an integrated approach to the study of trust, and the review, and discussions of trust theory in the rest of the chapter are guided by the model.

3.3 Trust Development

3.3.1 Trust and Context

Different contexts affect the processes of trust development by providing different forms of embeddedness that encourage or discourage trustworthy behaviour (Li 2016; Rousseau et al. 1998; Möllering 2006). In entrepreneurial trust development, context may refer to networks and social relations (Granovetter 1985), norms of contracts and power within specific networks and relationships (Amoako and Lyon 2014), specific interactions (Möllering 2006), industry-specific conditions as well as institutional environments particularly culture (Bachmann 2010; Saunders et al. 2010).

Networks, Relationships and Trust Building

The embeddedness or relational approach posits that in addition to individual freedom of action there is a need for reciprocity and mutuality due to the impact of implicit rules and social mores in embedded contexts. As a result, the relational approach emphasises the direct relationships of the entrepreneur to others and the assets of trust and trustworthiness that are embedded in these relationships (Tsai and Ghoshal 1998). Networks and relationships enhance trust building, cooperation and access to resources in the entrepreneurial process. The network approach emphasises that entrepreneurs are dependent on key relationships with actors within and outside the firm in the entrepreneurial process. This is significant given that entrepreneurs as individuals do not exist nor operate in a vacuum, but instead as actors who operate in social networks (see Granovetter 1985). Personal and organisational relationships constitute entrepreneurial networks (Hakansson et al. 1989). Personal networks comprise of relations between two individuals whilst interorganisational networks consists of autonomous organisations. However, inter-firm collaborations often originate from previously established networks of personal, informal relationships. Entrepreneurs rely on their strong and weak ties or personal and working relationships to gain information and resources. Figure 3.1 shows the importance of networks and relationships to trust development.

In the context of Africa, entrepreneurs rely more on networks and relationships and trust with intermediaries, suppliers, and customers based on long-term relationships (Ghauri et al. 2003; Lyon 2005). Chapters 4 and 5 of this book explain these issues further.

Contracts and power are two other important factors that can complement trust in interpersonal and interorganisational relationships and these will be explored in this section.

Trust and Contracts

The economic and sociological approaches to mitigating risks in economic exchanges have given rise to a debate on the relationship between contracts and trust in interorganisational relationships (Williamson 1979, 1985; Bradach and Eccles 1989; Rousseau et al. 1998). One key approach used by economists to explain the relationship between trust and contracts is transaction cost economics (TCE), spearheaded by Williamson (1985, 1993). The presence of opportunism subjects several exchange partners to risks and uncertainty, hence Williamson (1979, 1985) argues that substantial transaction cost in inter-firm relationships originates from the possibility of opportunism by any of the parties. Opportunism refers to ‘calculated efforts (by an exchange actor) to mislead, distort, disguise, obfuscate, or otherwise confuse an exchange party’ (Williamson 1985, 47). Williamson (1993) argues further that it is important for an exchange actor to devise contractual safeguards against such opportunism. In view of ‘predatory tendencies’ (Williamson 1993, 98), contracts or written agreements should be developed to monitor opportunistic behaviour of economic actors (Alchian and Demsetz 1972).

However, some researchers (e.g. Bradach and Eccles 1989; Nooteboom et al. 1997) oppose the TCE approach to trust and posit that it is trust rather than contracts that enhances economic exchanges. They suggest that trust economises on contract specification, enhances contract monitoring as well as offers material incentives for cooperation and reduces uncertainty. There is also disagreement on how trust complements or substitutes for contracts. While one group of studies suggest that the increase in the general complexity of contracts lead to increased trust (see Poppo and Zenger 2002), others (e.g. Malhotra and Murnighan 2002) assert that binding contracts that are aimed at promoting cooperative behaviour are more likely to decrease the level of trust and attitudes towards trust in collaboration. Macaulay (1963) and Beale and Dugdale (1975) also emphasise that, to some extent, presenting a contract signifies distrust and business people prefer not to have contracts. However, Nooteboom et al. (1997) suggest that trust can be either a complement or a substitute depending on the context.

In the contexts of smaller enterprises, in practice spelling out and enforcing exchange partners’ obligations in all conceivable ways in a contract is particularly expensive (Hart 1989). Small firms often forget and ignore contracting issues and thereby cause more conflicts due to the imperfections and subjective interpretations of contracts in SME interfirm relationships (Frankel et al. 1996). Therefore, trust can mitigate the inherent complexity and risks and to cover expectations about what partner firms will do in situations where expectations cannot explicitly be covered. In the context of entrepreneurship, the importance of legal contracts as the basis of interorganisational relationships varies between cultures (Höhmann and Welter 2005). While written contracts are the most common form of institutionalised trust in Western economies (Lyon and Porter 2010), in Africa, studies (Amoako and Matlay 2015) suggest that trust and mostly oral contracts that are not enforceable in a court of law are the norm. In this book, the author examines contractual arrangements that entrepreneurs and smaller businesses use to manage familiar and unfamiliar relationships that may or may not be across cultures in Africa.

Trust and Power

Trust and power seem to work in a similar way. Both mechanisms enable social actors to establish a link between their mutual expectations with each other based on a coordination of their actions (Bachmann 2001). Traditionally, power describes a phenomenon where someone imposes his or her will on others; and one person or group gives orders and the others obey (Taylor 1986). However, Foucault (1978) posits that modern power is in all social relations. He claims that ‘power is everywhere not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere’ (Foucault 1978, 92–93). Foucault (1978) argues that actors in specific relationships are positioned within network of power relations. Power is also present in all kinds of institutions, economic and social (Foucault 1980). However, in social relations, power is not used in the context of authoritarian rule but it facilitates the achievement of mutual goals for the actors in the social exchange process (Ap 1992).

Bachmann (2001) proposes that the risky nature of trust implies that trust remains a fragile mechanism even if it becomes established in a relationship; hence power is a more robust mechanism which even if misplaced does not entail as significant a loss as trust. Nonetheless, power like trust can break down, particularly when actors cannot enforce the sanctions inherent in the violation of power. In the context of entrepreneurial relationships, power exists in various forms and resides in resources such as knowledge, skills, tasks, money, strategy, and management, among others, and power can be exerted based on a larger firm’s influence on decision making within a smaller firm. Thus, the level of trust and the degree of cooperation depend partly on the sizes of the firms as well as economic power and this may lead to asymmetric trust when there is greater vulnerability on the part of one of the exchange partners due to power and resource dependence (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978; Zaheer and Harris 2006).

Interactions and Trust Building

Process theories posit that in circumstances where actors do not have prior relationships, do not know each other, and at the same time cannot rely on institutions, trust as a process is learned through interactions, knowledge, mutual experience, and the rules that emerge over time (Ring and Van de Ven 1992; Möllering 2006). In such circumstances, actors as agency assumes an important role in trust development, maintenance, and the changing of it and may require a leap of faith in trusting strangers based on blind trust (Möllering 2006, 80). The process involves reflexivity due to the inherent uncertainty, risks, and vulnerability. In such circumstances, trust could be calculative, routinised, or a reflexive process contingent on ongoing interactions between the actors and, as a process, trust involves a leap of faith (Möllering 2006). Even though such interactions may start relatively blindly or accidentally, they may become self-reinforcing in a process of reflexive familiarisation and structuration (Möllering 2006, 80). Often organisational trustworthiness results from the interactions between individual actors who act as boundary spanners or from groups in multilevel networks (Zaheer et al. 1998; Gillespie and Dietz 2009), within organisations and institutions.

Institutions and Trust Development

Institutions affect trustworthy behaviour due to the incentives they make available and the sanctions they impose on trustees’ mutual expectations in an exchange relationship (Welter and Smallbone 2006). In each country, the availability and nature of state and market support institutions as well as cultural institutions provide the different forms of embeddedness that encourage or discourage trustworthy behaviour (Welter and Smallbone 2006, 2011). Research suggests that state and market institutional orders, including government and state institutions such as legal and justice systems, the tax system, and other incentives offered by the institutional environment shape the level of trust and the ability to trust in a country (Zucker 1986; Welter and Smallbone 2010). There are thus fundamental differences between developed and developing economies regarding trust development in economic exchanges. The literature suggests that in developed economies, the presence of strong state and market institutions provide high levels of institutional trust that allows arm’s-length exchanges with limited information about new partners, due to the presence of legal safeguards, and sanctions that may be applied should the relationship fail (Welter and Smallbone 2006, 2011). In contrast, in developing countries personal relationships enhance economic exchanges where there is a lack of strong institutions. However, this view is contested in this book as in the midst of weak state institutions, informal institutions may substitute for and replace ineffective formal institutions (Estrin and Prevezer 2011), leading to the development of ‘parallel institutional trust’ which enhances entrepreneurship (Amoako and Lyon 2014) and this will be discussed in detail in Chaps. 4 and 6.

Trust also acts as an informal institution due to its role as a sanctioning mechanism (Welter et al. 2004) and yet informal institutions influence trust development processes. In every culture, there are sets of common beliefs and norms that shape mental models and entrepreneurial behaviour (Altinay et al. 2014). Culture based on sets of meanings, norms, and expectations underpin behaviour and trust building in networks and relationships (Dietz et al. 2010; Curran et al. 1995; Amoako and Matlay 2015). Chao and Moon (2005) draw from the metaphor of a ‘mosaic’ of multiple cultural identities to describe the many different cultures of an individual or an organisation. These cultural ‘tiles’ include nationality, ethnicity, sector/industry, organisation, and profession and they shape entrepreneurial trust development (Altinay et al. 2014).

Recent research on trust emphasises that actors from different cultures may have different cultural values, hence, the level, nature, and meaning of trust may be different across different cultures (Dietz et al. 2010). The differences may lead to dissimilar trust expectations and different behavioural rules in conflict situations (Zaheer and Kamal 2011; Ren and Gray 2009; Saunders et al. 2010). Consequently, trust building between exchange partners from different cultures may be problematic (Dyer and Chu 2003). Yet, this challenge may not be limited to national borders but may include interfirm relationships such as strategic alliances, joint ventures, and flexible working relationships due to differences in organisational cultures (Zaheer et al. 1998).

One of the key challenges in the context of a globalised world where cross-cultural trust building in relationships is imperative for entrepreneurs, is that country and regional specific cultural and institutional environments render the adoption of universal concepts and models of trust challenging and untenable (Bachmann 2010). However, there is a dearth of studies that consider how particular cultural contexts shape specific trust drivers (Li 2016). Chapters. 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 contribute to bridging this knowledge gap by examining how logics of specific, complex, socio-cultural institutions shape trust building in business relationships in Africa.

Case 3.1 Culture and Trust Development in Africa

Different African cultures have different cultural norms guarding how to establish trust with visitors and strangers during a first encounter. Hence, it is very important for strangers to understand how to respond to the kind gestures of their hosts in order to establish that they are not enemies and can be trusted. Looking at the cultural norm for welcoming visitors, different African cultures welcome their visitors by offering different items such as drinks and food. For example, the Ibos in Nigeria traditionally offer cola to their visitors while the Akan people of Ghana traditionally offer water to their visitors. However, in Rwanda, traditionally, hosts offer milk to visitors. In spite of the differences in the items offered, in all three cultures it is important for the visitor or stranger to accept the cola, water, or milk offered in order to establish the initial trust that he or she is not an enemy and has good intentions. Yet, the same cultural symbol may mean different things in different cultures. For example, while water is the norm in Akan culture, if a visitor in Rwanda request water instead of milk it will suggest that the visitor does not trust the host and this will in turn lead to distrust from the host.

Source: interviews

3.3.2 Trustor: Propensity to Trust and Trusting Behaviour

Psychological theories regard trust as an attitude and an expectation at the individual level and propensity to trust describes the trustor’s readiness to trust. The literature describes it in various ways; e.g. generalised trust propensity (Mayer et al. 1995). Mayer et al. (1995) define propensity to trust as the ‘stable within-party factor that will affect the likelihood the party will trust’ (Mayer et al. 1995, 725). It relates to the individual’s awareness and tolerance of vulnerability (Bachmann and Zaheer 2013), and refers to the default level of trust placed in others. It is an attribute that is relatively stable and a generalised expectation about the perceived trustworthiness of others (Rotter 1967). Propensity to trust is a trait that allows a generalised expectation about the trustworthiness of others as it shapes the level of trust an actor has for a trustee prior to the availability of information about a particular trustee. Propensity to trust may serve as a cognitive filter that shapes the nature of reality based on the frames and inferential sets that individuals use in the selection and interpretation of information and in deriving meaning (Markus and Zajonc 1985). Hence, it relates to culture and emphasises the dimensions of trust-related personality. It also suggests that disposition rather than direct experience or availability of information on the trustworthiness of others determines the individual’s level of trust (Blunsdon and Reed 2003).

People with different developmental experiences, personality types, and cultural backgrounds have different propensity to trust. Some scholars therefore suggest that propensity to trust influences the type of information that individuals attend to as those who have a lower disposition to trust are less positive and more suspicious of others and vice versa (see Bachmann and Zaheer 2013). People with low trust propensity will require far more evidence of trustworthiness to start trusting. Such people therefore need repeated evidence of trustworthy behaviour to alter their initial trust levels. Conversely, people with high trust propensity will require far less evidence of trustworthiness to start trusting (Bachmann and Zaheer 2013).

Hence, some individuals may over trust; that is they will repeatedly trust in situations that most people would not trust while others will not trust in situations that most people will trust. Over trust is ‘a condition where one chooses, either consciously or habitually, to trust another more than warranted by an objective assessment of the situation’ (Goel et al. 2005, 205). Over trust results in a condition of unguardedness that facilitates the exploitation of the trustor by the trustee. This is because actors who over trust are unlikely to engage in monitoring behaviour and may end up being more vulnerable to exploitation than actors who do not exhibit trust in the first place. Over trust may also lead to lock-in from high-trust relationships that may be unproductive (Gargiulo and Benassi 2000).

Conversely, actors may have distrust in a relationship, operating side by side with trust, independent of each other or comingle and influence one another (Zand 2016). Grovier (1994, 240) defines distrust as ‘the lack of confidence in the other, a concern that the other may act to harm one, that does not care about one’s welfare or intends to act harmfully, or is hostile’. Lewicki et al. (2006) suggest that cultural or psychological factors may cause biases in an individual towards initial distrust. Distrust causes suspicion and alienation and discourages offers of support, assistance, and constrains collaboration and the achievement of shared aims. Not surprisingly, distrust exists in weak relationships. This book focuses on trust even though occasionally the author refers to over trust and distrust.

Trusting behaviour refers to acting in a manner that shows some degree of trust or distrust of the trustee. Trusting behaviour originates from the trustor’s beliefs about some of the consequences of trusting shaped by information from the trustee. The trustor’s own assessment of the possible outcomes of promises that the trustee makes may also inspire trusting (see Swan and Nolan 1985). These may lead to perceptions of trustees’ trustworthiness. Together these shape the intentions to trust and trusting behaviour. Trusting behaviour reflects expectations of the trustee’s actions and the trustor accepts to rely on the trustee and thus becomes vulnerable. Even though being trustworthy influences trusting behaviour, it may not be a necessary condition for the trustor to place trust. Tanis and Postmes (2005) argue that it is expectations of reciprocity that appear to determine whether people will behave in trusting ways or not.

3.3.3 Trustee’s Trustworthiness

Actors place trust based on the trustee’s trustworthiness. Mayer et al. (1995, 717) define trustworthiness as: ‘the characteristics and actions of the trustee that will lead that person to be more or less trusted’. Thus, trustworthiness relates to how the perceptions of the characteristics and behaviour of the trustee form the basis on which the trustor becomes willing to be vulnerable. Trustworthiness originates from trustees’ perceived ability, benevolence, and integrity. The three dimensions of trustworthiness are different but related.

Mayer et al. (1995, 717–719) define ability as the skills, competencies, and characteristics that enable a party to have influence within some specific domain. Benevolence refers to the extent of the trustee’s willingness to do good to the trustor (not be opportunistic) aside from the profit motivation. Integrity ‘involves the trustor’s perception that the trustee adheres to a set of principles that the trustor finds acceptable’. However, Mayer et al.’s (1995) dimensions of trustworthiness have been criticised by commentators due to the emphasis on individualism that is prevalent in the United States and the West in general (Möllering 2006). One may understand this criticism since trust dimensions in collectivist cultures differ from those in individualistic cultures. While trustors from ‘individualistic cultures’ are more concerned with a trustee’s capability to honour promises, trustors from collectivist societies are more bothered with the trustees’ predictability, motivations, and endorsements from ‘proof sources’ such as other trusted parties or/and groups (Doney et al. 1998). For example, instead of integrity, benevolence, and ability shown by Mayer et al.’s Western-focused model, honesty, sincerity, and affection are the dimensions of trust in China. Interestingly, Mayer et al.’s (1995) model does not address these issues.

Interestingly, scholars have paid little if any attention to investigating the dimensions of trustworthiness in entrepreneurship in Africa where entrepreneurs rely on relationships and cultural influences (Lyon 2005; Amoako and Matlay 2015). The culture in Africa is different from Western and Eastern cultures.

3.3.4 Forms of Trust Developed

The literature suggests that there are two main types of trust: personal trust and institutional trust (e.g. Lyon and Porter 2010). This raises questions about whether or not organisational trust exists since, originally, trust is an individual-level phenomenon. Critics argue that only individuals have subjective mental states, expectations, and attitudes (Zaheer et al. 1998). However, some scholars insist that formal organisations can be forms of institutions; in this way, institutional trust subsumes organisational trust (e.g. Welter and Smallbone 2006). Nonetheless, in this book, the author analyses trust at the personal, institutional, and organisational levels due to recent recognition of how organisational trust influences the structure and performances of relationships between organisations (Vanneste 2016).

Personal Trust

The nature of relationships influences the development of trust. Personal trust results from the outcomes of prior exchanges (Zucker 1986). The initial knowledge of the exchange partner and demonstration of trustworthiness are critical in gaining (personal) trust (Chang et al. 2016). It may also depend on the characteristics of a group such as ethnic, kinship, and social bonds and from emotional bonds between friends, family members, and other social groups (Welter and Smallbone 2006). Interpersonal trust refers to trust between two people, it describes the extent to which a person is confident and willing to act based on the words, actions, and decisions of another (McAllister 1995). Interpersonal trust may also originate from organisations based on trust between boundary spanners and from long-standing bilateral business relationships involving partners or friends. In such relationships, even though there may not be any explicit rules set out to govern the relationship, actors assume that the partner will behave as expected. Norms, values, and codes of conduct govern these relationships (Welter and Smallbone 2006). For interpersonal trust, an individual trusts or does not trust another individual (Vanneste 2016).

In the context of entrepreneurship, scholars suggest that entrepreneurs need to build interpersonal trust with key stakeholders such as customers and suppliers particularly during market entry (e.g. Aldrich 1999). However, the relationship between personal trust and institutional trust is complex. Institutional trust may complement personal trust in contexts with developed institutions (Zucker 1986). However, personal trust becomes more important for entrepreneurial success in societies such as Africa where formal institutions are weak. This is because personal trust can exist regardless of the legal and political context whereas institutional trust may require stability and predictability based on legitimate societal institutions reflected by societal norms and values (Welter and Smallbone 2006).

Institutional Trust: Trust Within and Between Institutions

Institutionalists conceptualise trust as a phenomenon within and among institutions, as well as the trust individuals have in those institutions (Möllering 2006). However, there is a disagreement on whether formal institutions can be trusted or not. Scholars such as Möllering (2006) indicate that interfirm relationships benefit from reliable institutions only if the actors trust those institutions. Others, such as Zaheer et al. (1998), suggest that trust exists only between people.

Institutional trust allows relationships to develop based on expectations that all parties uphold legal measures and common norms. The presence of a high level of institutional trust allows arm’s-length exchanges with limited information about new partners in an exchange due to the presence of legal safeguards and sanctions that may be applied should the relationship fail (Welter and Smallbone 2006, 2011). In contrast, a lack of formal institutional trust hinders entrepreneurial relationship building and give rise to the need to compensate for trust development in other ways such as the use of informal institutions and social cultural, informal control mechanisms (Lyon et al. 2012).

Organisational and Interorganisational Trust: Trust Within and Between Organisations

March and Simon (1958) define organisations as a group of people. Organisational trust refers to trust reposed in organisations and in the processes and control structures of the organisation that enables the trustor to accept vulnerability when dealing with a representative of the organisation without knowing much about the particular representative (Zaheer et al. 1998; McEvily et al. 2003). Reputations and brands linked to trust in leaders or others in the organisation can lead actors to have this type of trust (Zaheer et al. 1998). Gillespie and Dietz (2009) and Dirks et al. (2009) corroborate that organisations are multilevel systems and the various components contribute to perceptions of an organisation’s trustworthiness as well as to failures (Gillespie and Dietz 2009, 28; Dirks et al. 2009).

Trust between organisations has recently emerged as an important concept that influences the structure and performance of relationships between organisations (Vanneste 2016). Studies in entrepreneurship have shown that interorganisational trust has many advantages, for example it reduces uncertainty and complexity in business operations, reduces transaction costs in contracting, facilitates networking and allows business relationships with strangers (Welter and Smallbone 2006, 472). However, trust can be risky as it makes the trustor vulnerable due to potential trust violations which can cause great damage to relationships between exchange partners (Lewicki and Bunker 1996; Dirks et al. 2009) and adversely impacts on a firm’s growth and even the survival of organisations (Bachmann 2001; McEvily et al. 2003).

In interorganisational relationships, one of the conceptual difficulties is to identify who trusts who. Zaheer et al. (1998) attempt to resolve this dilemma by suggesting that even though trust does not originate from firms but rather from individuals in an organisation, it is conceptually consistent to regard trust as being placed in another individual or a group of individuals such as a partner firm. Zaheer et al. (1998, 142) posit that in interorganisational exchanges ‘interpersonal trust refers to the trust placed by the individual boundary spanner in her opposite member’ in the partner organisation. On the other hand, interorganisational trust refers to ‘the extent to which organisational members have a collectively-held trust orientation toward the partner’ (Zaheer et al. 1998, 143). Zaheer et al.’s model suggests that trust at the interpersonal level has links to trust at the interorganisational level through the processes of institutionalisation (Zaheer et al. 1998, 143–144). During this process, individual boundary spanners establish informal commitments over time and these become taken-for-granted organisational structures and routines. Interpersonal trust of the boundary spanners becomes re-institutionalised and eventually influences the trust orientations of the other members of the organisations in their trust orientation towards the partner firms, thus showing the relevance of interpersonal trust in interorganisational exchanges. Therefore, interpersonal trust facilitates interorganisational trust and the attitudes of boundary spanners impact on norms of interfirm opportunism or cooperation. Vanneste (2016) also argues that interoganisational trust can also emerge from interpersonal trust through indirect reciprocity; a process that describes when kind and unkind acts are returned by others in organisational relationships.

Regarding SMEs’ interorganisational trust in African contexts, the author argues in this book that the distinction between interorganisational trust and interpersonal trust is unclear since entrepreneurs remain the key boundary spanners and decision makers for their organisations. Therefore, entrepreneurs remain the origin and object of trust since interfirm relationships mostly come into being because of their strategic decisions (Inkpen and Currall 1997). This may differ in other contexts particularly in larger organisations where decision making is not vested in any single individual but rather in a number of managers.

3.3.5 Trust Outcomes

Cooperation

Studies suggest that interorganisational trust directly offers a variety of positive outcomes. In particular, trust enhances cooperation between individuals and organisations (Ring and Van de Ven 1992; Saunders et al. 2010; Amoako and Lyon 2014). However, trust may not be a necessary condition for cooperation as power can also induce cooperation (Mayer et al. 1995). In interorganisational relationships, the degree of cooperation depends partly on the size of firms as well as economic power (Zaheer and Harris 2006). The literature on buyer-seller relationships suggests that trust may have a direct positive impact on financial performance. For example, trust directly enhances financial performance (Zaheer and Harris 2006) and competitive advantage (Barney 1991), and trust indirectly influences performance through, for example, reducing transaction and relationship-specific costs by reducing conflicts (Zaheer et al. 1998), opportunism, and control (Smith and Barclay 1997). However, in spite of the potential positive impact of trust on performance Katsikeas et al. (2009) remark that the relationship between trust and performance is complex and poorly understood, and trust may not improve outcomes under all circumstances.

Access to Resources

The resource-based view (RBV) suggests that availability and mobilisation of resources are critical for the entrepreneurial process (Barney 1991). Entrepreneurs deploy different strategies to mobilise resources needed to exploit opportunities. As stated in Chap. 2, one key strategy that entrepreneurs use is the development of personal and business networks to strategically access resources from the external environment (Granovetter 1985). However, trust fosters cooperation between individuals and organisations in networks and relationships (Ring and Van de Ven 1992; Lyon 2005; Amoako and Lyon 2014). Trust therefore allows entrepreneurs to access resources including ideas, motivations, information, capital, access to markets, skills and training, and the goodwill inherent in bureaucracy (Granovetter 1985). Trust is particularly important for SMEs as resources are limited and entrepreneurs and their firms often rely on partners to gain access to critical resources in order to manage uncertainty due to their limited expertise and capacity. However, the creation, upholding, and maintenance of trust involves costs in the form of a significant amount of time and resources such as gifts that may be expensive (Larson 1992; McEvily et al. 2003). Furthermore, trust entails risks and vulnerability and trusting may lead to the loss of resources when trust is violated.

3.4 Trust Violations

Trust is fragile and when violated can lead to considerable consequences (McEvily et al. 2003). Trust violations could be real or perceived based on instances of unmet expectations (Goles et al. 2009). At the personal level, Palmer et al. (2000, 248) define trust violation as unmet expectations regarding another person’s behaviour, or when a person does not act consistently with one’s values. However, changes in supporting commitments for the trustee at some stage at which it becomes untenable to act as expected may cause trust violations (Möllering 2006). Yet, trustees may also at times disguise ulterior motives and falsely invoke the socially desirable notion of trust in their attempt to exploit others (Möllering 2006).

In the context of organisations, trust violations could refer to perceptions of unmet expectation of a product or a service (Goles et al. 2009). Institutional trust violations, on the other hand, could result from unmet expectations about particular institutions. However, academics have shown very little interest in violations of trust by organisations and institutions in entrepreneurship and this study aims to contribute to knowledge in these areas.

Unlike organisational and institutional trust violations, there has been a number of studies on interpersonal trust violations (e.g. Lewicki and Bunker 1996; Kim et al. 2004; Dirks et al. 2009). However, there are a few studies that investigate the trustor’s perceptions of trust violations. One of the notable exceptions is Kim et al.’s (2004) study that draws on Mayer et al.’s (1995) dimensions of ability, integrity, and benevolence. The study suggests that perceived violations of ability and integrity lead to more decline in trust than perceived breaches in benevolence (e.g. Kim et al. 2004). The authors explain that trust violations that originate from perceived breaches of integrity or values may be generalised across other dimensions of trust due to stereotypes resulting from the belief that defective character transcends situations. This is because ‘people intuitively believe that those with integrity will refrain from dishonest behaviours in any situation, whereas those with low integrity may exhibit either dishonest or honest behaviours depending on their incentives and opportunities’ (p. 106). In spite of the insights that Kim et al.’s (2004) research offers on the subject, one can argue that since the study is based on controlled experiments their study downplays the complex relationships between calculation, cognition, and context. These assumptions about trust and its violations apparently ignore the differences between actors from different cultures (Dietz et al. 2010), as well as the potential subjective nature of interpretations of perceived trust violations by exchange partners across cultures, industries, markets, and relationships. These issues call for more investigations into trust violations in different contexts.

Understanding trust violations in interpersonal and interorganisational relationships is important since violations may lead to a reduction in subsequent trust and cooperation (Lewicki and Bunker 1996). In the context of organisations, trust violations may lead to considerable consequences such as raising concerns about why the victim may want to continue to buy from the offender (Goles et al. 2009). Business organisations that fall victim to trust violations may suddenly find themselves in a situation that threatens their very existence (Bachmann 2001). For example, when a supplier violates trust in a supply agreement, the firm that has fallen victim may suddenly find itself in a situation whereby it may not be able to meet customer demands and this may threaten its very existence. It may also lead to the victim engaging in negative word of mouth that may generate a multiplier effect that may go beyond the individual buyer’s intent not to engage with that particular seller (Goles et al. 2009).

Trust violations originate from information that differs from trustor’s expectations of behaviour of the trustees (Lewicki 2006; Kim et al. 2004). Trust violation may also originate from unreliability, harsh comments and criticism, or aggressive and antagonistic activities that occur as conflicts escalate (Lewicki 2006; Dirks et al. 2009). Perceived trust violations may originate from unsubstantiated allegations. However, exploration of perceptions of trust violations raises questions about whether both parties see the relationship and its violation in the same way. In relationships constituted on asymmetric power, the interplay of trust and control may shape not only the building and operation of trust (Bachmann 2001), but also perceived violations. A study of the context of trust violations also allows for the examination of power relations that shape organisational trust. While control may complement trust (Zucker 1986), the asymmetric nature of power in relationships (Inkpen and Currall 2004), means that violations may be perceived in very different ways by each party. There may be greater vulnerability on the part of one exchange partner in a relationship due to power and resource dependence (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978; Zaheer and Harris 2006), particularly so in contexts of SMEs involved in relationships with larger organisations. Furthermore, as common legal institutions and culturally specific norms are important in building trust, then there is also a need to understand how culture shapes perceptions of trust violations and the response to this. While this has been explored in theoretical contributions (Ren and Gray 2009; Zaheer and Kamal 2011) and controlled experiments there are very few examinations of trust violations in specific cultural contexts.

These issues therefore call for more investigations into how trust and the process of violation are embedded in existing social relations that may differ between cultures. The concept of trust violation is central to this book with a focus on how, in the weak institutional environments found in Africa, uncertainty and cultural differences can create greater threats to a relationship.

3.5 Trust Repairs

The key challenge following the violation of trust is finding ways to repair the damage and rebuild relationships. However, trust repair may be difficult due to the fragile nature of trust and the great damage that trust violations can cause to relationships between exchange partners (Lewicki and Bunker 1996; Dirks et al. 2009). Trust repair effort is defined as ‘activities directed at making a trustor’s trusting beliefs and trusting intentions more positive after a violation is perceived to have occurred’ (Kim et al. 2004, 105). Kramer and Lewicki (2010) refer to this as seeking to restore the willingness of [a] party to be vulnerable in the future’. Interestingly, trust repair is an emerging area of research that currently has seen a few studies, mostly based on theoretical and controlled laboratory experiments (e.g. Lewicki and Bunker 1996; Kim et al. 2004; Gillespie and Dietz 2009; Dirks et al. 2011).

Lewicki (2006) cautions that repairing trust may take time due to the need for parties involved to re-establish the reliability and dependability of the perpetrator over a period of time. At the interpersonal level, Lewicki and Bunker (1996) propose a trust repair model suggesting that trustors may effectively contain conflict or rebuild trust in the shorter term by managing the distrust inherent in every relationship and repairing the trust violated. To repair trust, they outline a four-step process: (1) acknowledge that a violation has occurred; (2) determine the causes of the violation and admit culpability; (3) admit that violation was destructive; and (4) accept responsibility. However, the main challenge of the model emanates from the willingness of the violator to play an active role that in many cases may not be likely. The model also assumes that the trustor plays a passive role in trust repair. The role of the violator is important and in a later experimental study Dirks et al. (2011) confirm that the trustor’s cognitions of repentance of the trustee play a role in trust repair.

In a similar study, Kim et al. (2004) found that apologies are only effective in repairing competence-based violations. Instead, they argue that denials are more effective for repairing violations of integrity and in contrast, actors may overlook violations of benevolence.

While the above models pay less attention to the role of context in trust repair processes, Ren and Gray’s (2009) theoretical framework on trust repair emphasises the role of culture in trust repair processes. It particularly emphasises that culture impacts the norms that delineate the violations and prescribes the appropriate restoration process. Ren and Gray (2009) outline four restoration mechanisms namely (1) accounts, (2) apologies, (3) demonstration of concern, and (4) penance. They stress that the victim’s perception of the type of violation and the national cultural values determine the processes of relationship restoration. Furthermore, they highlight that in collectivist societies, victims of trust violations in their attempt to repair trust are more likely to approach a third party. This observation supports Tinsley and Brodt’s (2004) declaration that collectivists tend to use intermediaries in the process of repairing relationships by relying more on covert expressions and thereby avoiding direct confrontation with perpetrators of trust violations. The studies of Ren and Gray (2009) and Tinsley and Brodt (2004) suggest that cultural differences in cross-cultural entrepreneurial relationships add to uncertainty and create further challenges for repairing trust.

Concerning organisational trust repair, Gillespie and Dietz (2009) argue that in organisational contexts, the target for trust repair may be individuals or groups of individuals that make up an organisation. Consequently, trust repair at the organisational level creates a further degree of uncertainty and may be more difficult due to the multiplicity of organisational membership and the need for individuals to change their views towards the violating organisation.

Gillespie and Dietz’s (2009) theorise further that interpersonal trust repair is not readily transferable to the organisational level because organisations are multilevel systems and the various components contribute to perceptions of an organisation’s trustworthiness as well as to failures (Gillespie and Dietz 2009, 128). They argue that trust violations, which they also refer to as organisation failures, may result from malfunctioning of any of the components of an organisation. To repair organisational level trust, Gillespie and Dietz (2009) propose a four-stage model, viz.: (1) immediate response, (2) diagnosis, (3) reforming interventions, and (4) evaluation. They theorise further that trust-substantive measures such as regulation can repair trust through taking actions that would deter future breaches. Thus, confirming earlier studies that ‘legalistic remedies’ such as controls involving policies, procedures or monitoring (Sitkin and Roth 1993), punishment and regulation of the perpetrator, the voluntary introduction of monitoring systems, and sanctions (Nakayachi and Watabe 2005) all help to restore trust because they increase the reliability of the behaviour of the perpetrator. Existing research contributions therefore call for a greater understanding of these repair processes operating at the organisational level rather than the current focus on the interpersonal (Gillespie and Dietz 2009). This will require an understanding of the inter-relationship between interpersonal trust repair and organisational trust repair.

In this book, the interest in trust violations and trust repairs arises due to the need to maintain and repair trust in cases of violations in entrepreneurial relationships to facilitate access to resources and markets by smaller organisations in Africa in particular. Since conflicts may inevitably arise leading to the failure of some entrepreneurial relationships, trust repair may allow entrepreneurs to use alternatives to litigation through arbitration and bargaining as well as negotiation for the settlement of disputes without resorting to adversarial conflicts (Lewicki and Bunker 1996). In this book the author argues that by understanding the processes of trust repair in entrepreneurial relationships, entrepreneurs may be able to build and use relationships and networks to access critical resources for growing their businesses. The author therefore explores how cultural norms and power relationships shape the actions of both perpetrator and the violated parties. This chapter contributes to knowledge on these complex issues by specifically examining how Africa’s complex socio-cultural institutions shape trust building, trust violations and trust repairs in business relationships.

3.6 Conclusion

This chapter reviews the literature and highlights that trust is needed due to the presence of risk and uncertainty in economic transactions. It also highlights the debates on definitions of trust, its development, violations, and repairs in interorganisational relationships. Psychological models suggest that trust may be shaped by propensity to trust, while economic models such as TCE emphasise that the decision to trust or not to trust originates from a careful rational reasoning of consequences (Gambetta 1988; Williamson 1993). On the contrary, sociological approaches suggest that trust development can be habitual and routine because trust is embedded in institutions and is taken for granted (Granovetter 1985; Zucker 1986). Trust may also be a process that involves reflexivity (Möllering 2006). This study therefore offers an integrated approach by adopting a working definition of trust as an ‘an expectation that is shared by people in an exchange that things and people will not fail them in spite of the possibility of being let down’. This definition suggests that expectations based on the trustworthiness of the trustee, the nature of specific relationships, and accepted norms within each context influence the trustor’s trusting behaviour. This definition also recognises that trust is fraught with risks and vulnerability.

This chapter contributes to knowledge through presenting a holistic model (Fig. 3.1) that incorporates the trustor, trustee, their relationships, interactions and institutions that shape trust development, and the outcomes of trust. The model suggests that trust originates from a trustor’s propensity to trust and trusting behaviour as well as a trustee’s trustworthiness based on his or her ability, integrity, and benevolence (Mayer et al. 1995; Kim et al. 2004). “The framework further shows that contextual factors namely: networks and relationships, contracts, power, interactions, and formal and cultural institutions influence the development of trust (Granovetter 1985; Möllering 2006; Zucker 1986; Bachmann and Inkpen 2011)”.

Yet, the development of the model is informed by existing studies mostly conducted in the West and there is little understanding of trust development processes in other contexts including emerging economies such as Africa (Amoako and Lyon 2014; Wu et al. 2014). Scholars have therefore called for more investigations in other contexts to examine the nature of institutions, particularly networks and relationships, and cultural norms that influence trust development, trust violations, and trust repair (see Li 2016; Bachmann et al. 2015). There is also little knowledge of how context affects interpretations of what constitutes trust violations and the acceptable norms for repairing violations of trust in interorganisational relationships (Amoako 2012). Chapters 6, 7, and 8 will examine these issues in detail in an African context based on empirical studies in Ghana conducted by the author. The next chapter (Chap. 4) identifies the key common cultural institutions that facilitate trust development in entrepreneurial relationships in Africa.