7.1 Introduction

Trust is important as it binds partners together and reduces uncertainty by promoting long-term cooperation in interorganisational relationships (Fink and Kessler 2010). Yet, trust is fragile as it may take years to develop in relationships, but can be destroyed within a short time if one party engages in a behaviour that violates the trust between the parties (Lewicki and Bunker 1996). All the same, trust violations are common at individual, organisational, and institutional levels (Gillespie and Dietz 2009; Kramer and Lewicki 2010). In interpersonal relationships, trust violations result from the behaviour of individual partners. Similarly, in organisational and institutional settings the behaviour of boundary spanners and officials primarily determine when and how trust is violated since, in the end, it is individuals that trust and not organisations per se (Ring and Van de Ven 1992; Zaheer et al. 1998). Yet, organisational systems and processes may also fail resulting in trust being violated by organisations (Gillespie and Dietz 2009).

Lewicki (2006) explains that trust violations originate from information that differs from a trustor’s expectations of a trusteee’s behaviour. However, it is not only unacceptable behaviour that can influence trust violation, the perceptions that drive frustrations and feelings of violations can also influence trust violations. Trust violation can have serious implications for individuals, organisations, and society at large (Bachman et al. 2015). It can result in a reduction of trust and cooperation and may cause great damage to relationships between exchange partners (Lewicki and Bunker 1996; Dirks et al. 2009; Bachman et al. 2015). In the context of business, trust violations may lead to considerable consequences. For example, when trust is violated between a buyer and a seller or between firms collaborating in a horizontal relationship, the firm that becomes the victim may suddenly be in a situation that threatens their very existence (Bell et al. 2002; Bachmann 2001).

In spite of the potential serious consequences, currently, there are few studies that have investigated trust violations in organisational settings and at the institutional level (Bachman et al. 2015). Surprisingly, among the few existing studies, most adopt experimental and rationalist calculative approaches that emphasise the role of agency based on Mayer et al.’s (1995) dimensions of ability, benevolence, and integrity (Kim et al. 2004; Dirks et al. 2009; Gillespie and Dietz 2009). Despite the significant contributions made by these studies, the influence of context is ignored. Different contexts influence the processes of trust development by providing different forms of embeddedness that encourage or discourage trustworthy behaviour (Li 2016; Rousseau et al. 1998; Möllering 2006). Hence, it is expected that the processes of trust violations may differ based on the differences in expectations within different contexts (Saunders et al. 2010; Amoako 2012). Yet, scholars have done very little work to enhance our understanding of how context influences trust violations (Bachman et al. 2015; Amoako and Lyon 2012). Context in this book include state and market institutions, cultural institutions, networks and relationships, sector and industry, and markets.

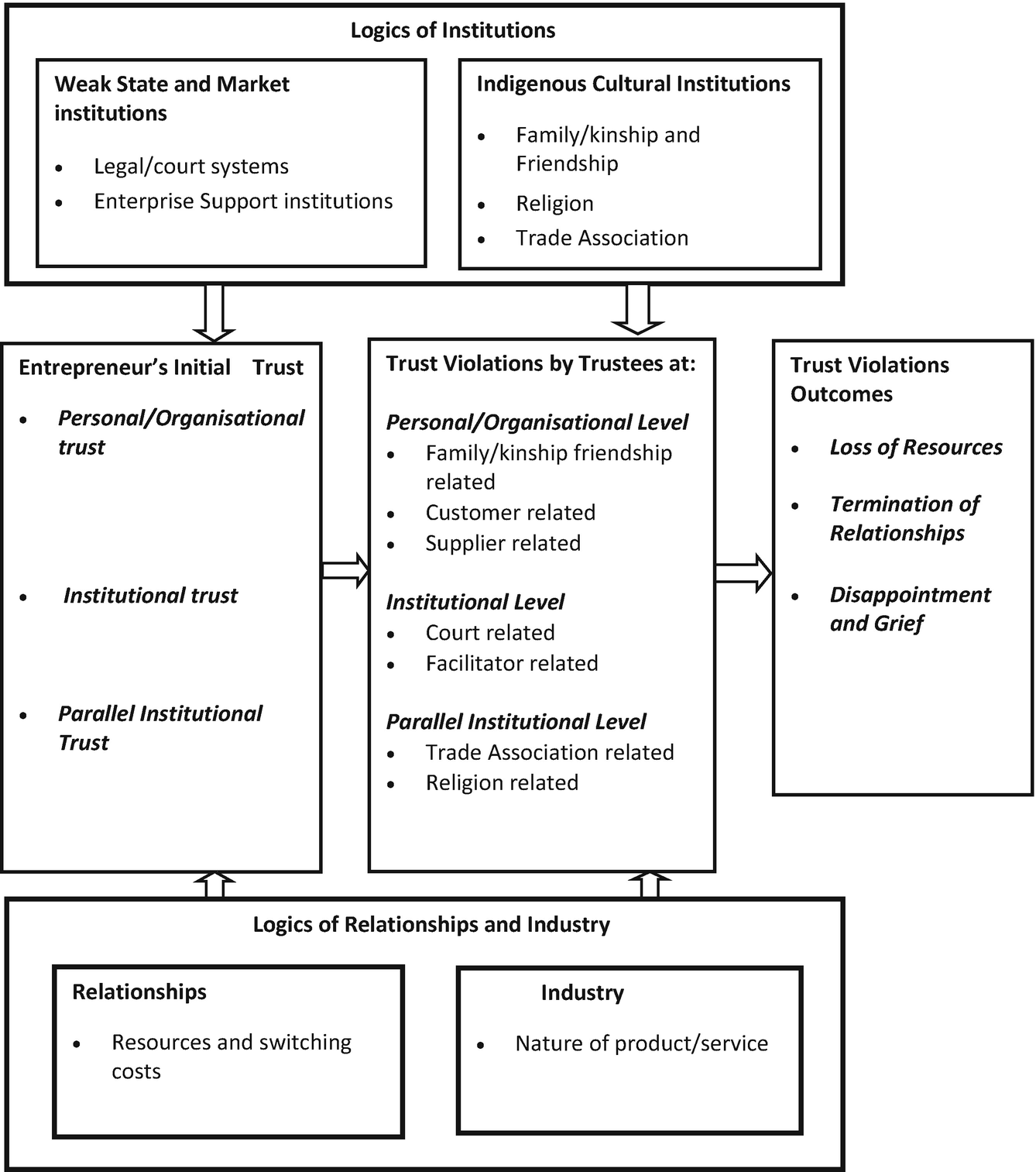

The aim of this chapter is to explore and extend our understanding of how weak state and market institutions, cultural institutions, personal and working relationships, industry, and markets shape the processes of trust violations in entrepreneurial relationships in Ghana (Amoako and Lyon 2014; Bachmann 2010).

Entrepreneurs and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Ghana, as in other African countries, operate in countries with limited institutional trust in state and market institutions. As a result, parallel institutional trust from cultural institutions (Amoako and Lyon 2014), trade associations, and industry-specific norms in addition to personal trust in networks and relationships enhance economic activity (Amoako and Matlay 2015; Hyden 1980; McDade and Spring 2005).

The analysis and discussions in this chapter focus on the entrepreneur, and how the logics of societal institutional orders such as weak legal systems, family/kinship, religion, trade associations, and industry shape the processes and interpretations of trust violations in an African context.

The discussions are based on three core questions: (1) ‘How is trust violated in entrepreneurial relationships?’, (2) ‘What institutional logics influence interpretations of trust violations in entrepreneurial relationships and how?’ and (3) ‘What are the outcomes of trust violations?’

Trust violation in entrepreneurial relationships. (Source: Own research)

This chapter contributes to our understanding of how entrepreneurs owning and managing smaller businesses in Africa experience and interpret trust violations. It presents a framework that incorporates the trustor, trustee, institutions, relationships, and industry that shape the processes of trust violations. Currently, such a holistic approach is lacking in the literature. It also draws attention to how the concept of trust violations remains unclear due to the logics of: culturally specific institutions, and of relationships and industry that shape interpretations of trust violations in entrepreneurial relationships. It further highlights that trust violations can lead to varying negative financial, psychological and social costs to entrepreneurs and yet the literature has not paid attention to these outcomes. The rest of the chapter is organised as follows: Sect. 7.2 discusses the entrepreneur’s initial trust. Section 7.3 focuses on how trustees violate trust and the different levels and forms of trust violations. Section 7.4 examines the institutional logics that shape entrepreneurs’ interpretations of trust violations. Section 7.5 presents the outcomes of trust violations and Sect. 7.6 offers the conclusion.

7.2 Entrepreneur’s Initial Trust

Entrepreneur’s initial trust expectations are based on their expectations of the actions and behaviour of the trustee that allows him or her to be more or less trusted (McKnight et al. 1998; Mayer et al. 1995; Rousseau et al. 1998). Within entrepreneurial relationships in Ghana, the actions and behaviour of the partner entrepreneur or the key boundary spanner of the larger organisation or institution forms the basis on which the entrepreneur (trustor) becomes willing to be vulnerable.

At the personal/organisational level, an entrepreneur’s initial trust is shaped by the logics of weak legal systems and those of family/kinship and friendship. An important initial trust expectation is that a key business partner who may be a family member or regarded as a ‘family’ member must be willing to be relied on or to support the entrepreneur in economic exchanges.

Initial trust at the institutional level is based on trust in state and market institutions such as government, legal and justice systems, the tax system, and other enterprise support institutions that offer incentives in the institutional environment (Zucker 1986; North 1990; Welter and Smallbone 2010). While the processes, culture, and systems of institutions are important for institutional trust development, it is often the character, actions, and behaviour of officials and the key boundary spanners of institutions, and how consistent they are regarding the rules, regulations, and objectives of those institutions that determine trust in those institutions (Mitchell 1999).

Initial parallel institutional trust refers to trust in the officials and the institutions that run parallel to state institutions, notably trade associations and religion. The honesty of the leaders of trade associations and the logics of social capital based on regulation, conflict resolution, advocacy, legitimacy, networking, market information, references regarding reputation and creditworthiness, developing skills of members, and providing welfare to members in times of crisis form the basis of parallel institutional trust. Similarly, honesty, brotherliness, shared values, and caring for one another based on logics of religion also provide the basis of parallel institutional trust. Based on these logics, more informal personalised relationships are developed to enhance economic activity. As a result, initial trust expectations in Ghana may have stronger elements of obligation between exchange partners than in other countries, particularly in the West where the emphasis is more on individualism (see Chap. 6). Trust violations therefore result from breaches in these expectations.

7.3 Trust Violations by Trustees

Forms and incidents of trust violations in entrepreneurial relationships in an African context

Type of trust violated | Forms of violation | Incidents of violations |

|---|---|---|

Personal and organisational trust | Family-related | Family members misappropriating funds Family members as poor trade creditors and borrowers Family members not adhering to contract terms |

Customer-related | Disappearing after receiving goods on trade credit from entrepreneurs Reducing the agreed price of goods already supplied on trade credit Not paying for goods supplied on trade credit on time Not paying for goods supplied on trade credit at all Telling lies about the timing of depositing money at the bank for entrepreneurs Going behind the back of entrepreneurs to establish a warehouse and competing directly Exploiting loopholes in contracts to take advantage of entrepreneurs | |

Supplier-related | Disappearing after receiving trade credit to supply goods Diverting money advanced for the supply of goods to other uses Not supplying goods already paid for on time Supplying poor quality products Supplying a smaller quantity of the goods already paid for | |

Institutional trust | Facilitator-related | Perceptions of state-backed bodies involved in nepotism and corruption |

Court-related | A court in Ghana allegedly brought forward the time of a case without telling the entrepreneur Inability to pursue customers in the European Union due to lack of jurisdiction of courts in Ghana A land dispute pending more than six years after the first hearing | |

Parallel institutional trust | Trade association-related | Leaders of trade associations exploiting opportunities for themselves Agents in West African markets delaying payments against the norms of the efiewura system |

Religion-related | Belief in the use of black magic and juju by competitors to destroy businesses Exploitation by fake and unscrupulous religious leaders |

7.3.1 Personal/Organisational Trust Violations

In this section the author discusses personal/organisational trust violations based mostly on empirical data. It is important to remember that in Chaps. 3 and 6 we saw that in the context of SMEs in Africa, the distinction between interpersonal trust and interorganisational trust is ambiguous since entrepreneurs owning SMEs remain the key boundary spanners and decision makers for their organisations (Amoako 2012; Kuada and Thomsen 2005). As a result, in this book, interpersonal trust and interorganisational trust are not regarded as distinct even though they may be different in the context of larger organisations where a number of managers and boundary spanners may be involved in trust development processes. Similarly, interpersonal trust violations and interorganisational trust violations are not distinct but regarded to comingle at personal/organisational levels.

Interpersonal Trust Violations

Interpersonal trust violations has been conceptualised in different forms. For example, Kim et al. (2004) and Janowicz-Panjaitan and Noorderhaven (2009) draw on trust dimensions of ability, integrity, and benevolence (Mayer et al. 1995) to suggest that violations of trust involve breaches of ability, integrity, and benevolence. Breaches of integrity refers to violations in which the perpetrator purposefully engages in acts that differ from the ethical or moral expectations of the trustor. Kim et al. (2004) suggest further that violations of integrity lead to more decline in trust than perceived breaches in benevolence (Kim et al. 2004; Dirks et al. 2009). Accordingly, perceived violations of integrity or values may be generalised across other dimensions of trust due to assumptions that people with integrity will refrain from dishonest behaviour in any situation, whereas those with low integrity may exhibit either dishonest or honest behaviour depending on their incentives and opportunities. Competence violations refer to when the trustee unintentionally engages in an incompetent act due to lack of ability to do an activity correctly or when a mistake is committed. However, as argued earlier in Chap. 3 and in the introduction to this chapter, most of the existing studies downplay the complex relationships between calculation and context (Amoako 2012).

In interorganisational relationships, the conceptualisation of trust violations becomes complex because of the multiple levels of organisational trust. Gillespie and Dietz (2009) and Dirks et al. (2009) corroborate that organisations are multilevel systems and the various components contribute to perceptions of an organisation’s trustworthiness as well as to failures (Gillespie and Dietz 2009; Dirks et al. 2009). Even though some dimensions of trust can be covered in written contracts or agreements it is the soft criteria that exist in mutual beliefs, perceptions, and informal obligations in a buyer-supplier relationship that form the psychological contract and when breached trust is also violated (Hill et al. 2009).

At the personal/organisational level, trust violation occurs when the actions and behaviour of individual family/kinship members and friend who are partners involved in the business, or managers and leaders owning and managing partner customer or supplier SMEs or larger organisations do not meet the expectations of the entrepreneur.

Family/Kinship Related Violations

Violations of trust by family members in business is common in Ghana. Amoako and Lyon (2014) report that in spite of the benefits of the family in enhancing entrepreneurship (see Chaps. 4, 5 and 6), entrepreneurs often encounter challenges in enforcing agreements with family members. Family members may also embezzle funds when employed in businesses (Amoako and Matlay 2015). Hart (2000) posits that kinsfolk may often make poor borrowers in Ghana. Interestingly, the paradoxical role of family/kinship is not limited to Ghana but instead it is a common observation across a number of African countries. These violations relate closely to the norms of obligations of the family/kinship systems in Ghana and Africa which oblige entrepreneurs to provide for members of the extended family. Nonetheless, there are a number of very successful family businesses in Ghana and these are guarded by values that encourage commitment, accountability, and trustworthiness.

Customer-Related Violations

Customer-related trust violations are quite common in Ghanaian and West African markets. An entrepreneur’s customer expectations are based on honesty, reputation of the customer, access to trade credit, observing norms of trade credit, and sharing market information. However, breaches of these expectations are also quite common (Amoako 2012; Amoako and Lyon 2011).

In the domestic markets, trust violations relating to breaches of honesty occur when a customer does not keep promises regarding oral or written contract arrangements. For example, some customers may tell lies about the quality of products already supplied in order to reduce the agreed price of the goods. At times, other customers may renege on pledges to pay money at the agreed time. A few dishonest customers may not pay the money at all and, in rare and extreme cases, other dishonest customers could disappear after receiving goods/services on credit.

While incidents of trust violations are also quite common in the West African markets, trade associations, families, and religious organisations offer the safety net that often protects entrepreneurs from these opportunistic traders. In the face of these risks, entrepreneurs often test and observe how customers keep promises regarding agreements. Particularly, violations of promises to pay trade credit for goods or services supplied is taken very seriously and may lead to a reduction or abrogation of the trade credit arrangement. Furthermore, entrepreneurs rely on trade association membership as a guarantee of help to get their money back in cases of default in West African markets. Similarly, leaders and members of families and religious bodies may also intervene to enforce contracts. These conflict resolution methods will be discussed in more details in Chap. 8.

Similarly in international markets, customer-related violations of trust range from dishonest customers telling lies about the quality of products already exported in order not to pay the agreed full price of the goods already supplied, delaying payments, breaching the terms of legal contracts and memorandums of understanding (MOUs), exploiting loopholes in contracts, including non-enforceable clauses in agreements, to covertly seeking changes to contract terms in order to take advantage of SME exporters. Customers may also violate trust by not sharing information relating to changes in market demand and prices. However, trust violations relating to reputation is rarely mentioned probably because entrepreneurs may not start a trust-based relationship with customers whose reputations are knowingly tarnished.

Supplier-Related Violations

Suppliers’ trust expectations are based on honesty, supplying quality products/services, punctuality relating to meeting supply deadlines, access to trade credit and observing the norms of trade credit, the reputation of the supplier, and sharing market information. Yet, supplier-related trust violations are common in domestic, West African, and international markets. Entrepreneurs may experience breaches of honesty from some suppliers who may attempt to take advantage or defraud them by not keeping promises regarding contracts, product and service specifications, the right quality and quantity, and delivery times, or misusing trade credit for purposes other than supplying the goods/services already paid for.

To Ghanaian internationally trading entrepreneurs, another key supplier-related trust violation is being supplied with poor quality products/service. In particular, when expectations based on previously agreed specifications are not met. Yet, supplier-related violations concerning poor-quality products/services may not necessarily result from dishonesty but from other factors such as poor equipment or poor practices, which may not be intentional. In such instances, some entrepreneurs offer training and technical support to enable suppliers to meet the high specifications required. In contrast, dishonest suppliers may intentionally attempt to conceal the defects of their products, particularly when transactions are one off. Yet in either case, the supply of poor quality products/services puts the reputation of smaller businesses at risk and may result in loss of contracts with customers.

Another supplier-related trust violation relates to punctuality; that is, missing delivery deadlines. Entrepreneurs have expectations of punctuality in order to meet their obligations to their customers in local, West African, and international transactions. Yet, some suppliers, especially those without experience of Western business norms, may underestimate meeting the stringent deadlines required by entrepreneurs due to the norms of African punctuality. As discussed in Chap. 4, the cultural-specific norms of ‘African punctuality’, which refers to the flexible use of time in Ghanaian and African contexts, could be a major issue in relationship building in Ghana and Africa. Nonetheless, as stated in Chap. 6, entrepreneurs do not yield to these norms but instead respond by teaching new suppliers new norms of punctuality (Amoako 2012; Amoako and Matlay 2015).

One more supplier-related trust violation is the breach of trade credit terms. As discussed in Chap. 6, in competitive sectors entrepreneurs advance trade credit to suppliers. The expectation is that suppliers will keep the terms of trade credit by supplying the right quantity of goods/services at the right time. Yet, opportunistic suppliers may default and/or divert goods or services to another buyer. In extreme but rare cases, some suppliers apparently disappear after receiving payment advances for the supply of goods/services. To mitigate this, entrepreneurs often visit homes and workplaces and involve third parties such as family members and long-term customers or suppliers as witnesses to trade credit agreements.

7.3.2 Institutional Level Trust Violations

Institutional level trust violations originate from breaches of the processes, culture, and systems of institutions that are important for institutional trust development. Nonetheless, it is often the dishonesty and corruption of officials and the key boundary spanners of state and market institutions that determine trust in those institutions (Mitchell 1999).

Court-Related Violations

Entrepreneurs widely perceive the judiciary and legal systems and the courts to be weak and corrupt (Amoako and Lyon 2014). In particular, allegations of corruption in the judiciary and courts is common in the domestic market. These allegations relate to demands for bribes by dishonest officials and judges to the long processes involved in court resolution of commercial disputes. In the context of international trade, the main concerns of entrepreneurs centre on the inability of the courts to resolve disputes with international partners who do not live in Ghana. The courts in West African countries are equally perceived to be corrupt and entrepreneurs raise security concerns as well.

Facilitator-Related Violations

The forms of violations dubbed facilitator related refer to breaches of trust by officials of state-backed enterprise-support institutions. In Ghana, incidents of institutional trust violations also relate to officials of state institutions involved in enterprise support breaching trust. Allegations of dishonesty, bribery and corruption, and/or favouritism are cited by entrepreneurs as violations of trust by officials of state-backed enterprise-support institutions like the Ghana Export Promotion Authority (GEPA), National Board for Small Scale Industries (NBSSI). For example, there are allegations that money and support meant for internationally trading entrepreneurs are at times diverted by unscrupulous officials to their cronies who may not be involved in international business (Amoako 2012).

7.3.3 Parallel Institutional Trust Violations

Trade Association Related Violations

While trade associations serve as parallel institutions to the courts and provide some certainty to entrepreneurs in Ghana, there are allegations of violations of trust in some of the associations. Amoako and Lyon (2012) cite instances where some leaders of trade associations abuse their positions by exploiting opportunities for themselves instead of making them known to their members. Parallel institutional trust violations also result from allegations of the misuse of association funds and fraudulent accounting systems by association leaders (Amoako 2012).

Religion-Related Violations

Religious norms that encourage superstition are widespread in Africa and Ghana and can lead to violations of trust in entrepreneurial relationships (Amoako 2012). In particular, these violations may result from perceptions that customers or partners are able to exploit or abuse through the use of black magic, locally referred to as juju, to take advantage of their creditors or sponsors. Furthermore, there are perceptions that competitors can also destroy the businesses of others with juju and witchcraft. Hence some entrepreneurs often make references to God, Allah, the smaller gods, and prayers as bastions of protection for themselves and for their businesses.

Religion-related violations of trust also include the activities of fake religious leaders exploiting some entrepreneurs who may be followers. There are instances where Christian, Muslim, and Africanist religious leaders make claims to authority and authenticity by fraudulently faking miracles and connections to the spirits in order to deceive and defraud entrepreneurs and other followers in order to enrich themselves. De Witte (2013) cites instances where some Pentecostal pastors use electric touch machines to fake the transmission of divine power from the holy spirit to followers. Table 7.1 presents a summary of incidents of trust violations and the levels at which they occur.

7.4 Logics of Institutions Influencing Interpretations of Trust Violations in Ghana

A key challenge in understanding trust violation in entrepreneurial relationships is how context and particularly institutional logics influence interpretations of violations. The challenge is based on the premise that logics of weak state and market institutions, relationships, industry, and cultural institutions provide the cognitive filters or frames and inferential sets that actors utilise in the selection and interpretation of information (Kostova 1997; Gibson et al. 2009). In this chapter, the logics include: norms relating to relationships, sectors, and industry; and cultural institutions that are used to interpret what constitutes a violation (Amoako and Lyon 2011; Amoako 2012). Therefore, the definition of what constitutes trust violations in entrepreneurial relationships remains vague as it is predominantly shaped by norms of weak legal and support institutions, family/kinship, religion, trade association/industry norms, and power based on the nature of products/services, the nature of benefits derived, and individual agency. As a result, one party may perceive that trust has been violated while the other party may not realise this, particularly where there are differences in culture and expectations.

Logics of State and Market Institutions

Weak Legal Systems/Courts and Support Institutions

Interpretations of trust violations by internationally trading SME entrepreneurs in Ghana are influenced by the logics of weak judiciary and court systems and enterprise support institutions including the financial institutions. In a context where entrepreneurs seldom use the courts due to perceived corruption, long delays, cumbersome processes, and high costs, often violations of trust are either ignored or regarded as acceptable as the resources involved in pursuing legal redress for a breach of trust may be costly while the outcome may often be limited. Similarly, perceptions of inaccessible and unaffordable legal systems in both West Africa and international markets discourage entrepreneurs from using the courts in these markets. Entrepreneurs exporting to international markets also perceive the legal systems to be expensive due to high costs of travelling abroad and the legal fees (Amoako and Lyon 2014; Amoako 2012).

Yet, apart from the weak legal/court influences, a number of cultural-specific norms shape interpretations of trust violations.

Case 7.1 Ghanaian Court Trust Violations

Ama is a Ghanaian female entrepreneur who lived in the United States where she became familiar with the market demand for shea butter. When she returned to Ghana in 2002, she founded a company that processes shea butter for export to the United States. After operating for three years, the business started growing and so she acquired a piece of land to build a new plant. However, Ama encountered problems with the documentation for the property and so she went to court to seek redress. However, to her surprise, the case was in court for six years and was still pending at the time of the interview. Accordingly, Ama has decided not to deal with the courts in Ghana any more. She lamented that, ‘If I start dealing with you and I realize that you will end the relationship in court I stop’.

Source: from an interview with an anonymised respondent.

Logics of Indigenous Cultural Institutions

The limited institutional support from the courts and state institutions render it necessary to develop and manage personalised networks and relationships to enhance access to resources and affordable credit and conflict resolution. Family/kinship norms of reciprocity and obligations linked to real family members and business partners regarded as family members within relationships allow some of the entrepreneurs to either ignore violations or to regard violations as acceptable. Nevertheless, as stated in Chaps. 5 and 6, a number of entrepreneurs do not internalise these norms and may decide not to work with family members due to past negative experiences.

Religious norms serve as filters used in interpreting trust violations and enable some entrepreneurs to continue working with partners who may abuse the trust placed in them by the entrepreneur. For example, religious norms based on fatalism may inform entrepreneurs’ interpretations of trust violation by attributing violations to God, Allah, or the gods. Similarly, norms of forgiveness found in religion occasionally influence entrepreneurs’ decisions to ignore violations of trade credit agreements. The evidence therefore suggests that religion impacts on entrepreneurs’ interpretations of trust violations.

Norms of trade associations determine the expectations of the acceptable levels of behaviour of members and leaders in relationships with partners. As a result, trust violations are interpreted based on norms which may vary between markets and industries. For example, the dominance of the efiewura system in West African markets has empowered actors to dictate the terms of trade with regard to payments timing which may last from a few days to several weeks and yet entrepreneurs accept these norms and usually do not regard delayed payment as a trust violation.

Logics of Relationships

The norms of specific relationships influence interpretations of trust violations. Particularly, when the resources and benefits derived from a specific relationship are substantial, entrepreneurs owning and managing SMEs often consider the switching costs and ignore violations by such partners. For example, entrepreneurs often ignore delayed payments by larger organisations in domestic and international markets (Amoako and Lyon 2011; 2012), in particular, when the larger organisation remains the key customer that buys all or most of the products/services. Similarly, the violation of trust by partners who may fund or provide critical support services such as training on international standards, packaging, and issues pertaining to shipments may be ignored with entrepreneurs having little option but to continue working with the more powerful partners. Similarly, powerful suppliers such as small-scale mining companies supplying gold are able to default without entrepreneurs being able to withdraw trade credit deposits. Given the high switching costs, entrepreneurs and SMEs often put up with these challenges and continue to work with their more powerful partners.

Logics of Industry

The nature of the industry and the product/service remains a key factor in perceptions of trust violations. For example, in both West African and international markets entrepreneurs trading in agricultural products are often more vulnerable and more dependent on their customers abroad. Their dependency is due to the lack of refrigeration for fresh agricultural products such as eggs and fresh vegetables which have short shelf lives. This constraint influences the decisions of entrepreneurs to continue to supply their customers who may default in the payment of trade credit. For example, some entrepreneurs producing fresh eggs in Ghana continue to encourage customers who have defaulted to settle their debts by instalments as they continue to supply them, particularly when there is a glut in the domestic market.

Logics shaping perceptions of trust violations

Logics of | Description of impact on perceptions of trust violation |

|---|---|

Legal/courts system | Due to allegations and incidents of corruption by some judiciary and court officials, most entrepreneurs do not go to court but instead either ignore or regard violations as acceptable |

Enterprise support institutions | Some entrepreneurs respond to lack of support from enterprise support institutions by developing personal trust-based relationships within which trust violations may be ignored due to norms of obligation and reciprocity |

Family/kinship/friendships | Family members, kinsmen, friends, and community leaders draw on family norms of obligation and forgiveness to influence and at times coerce entrepreneurs to ignore trust violations in cases concerning a ‘family member’, friend or community member. |

Religion | Religious-fatalistic beliefs influence some entrepreneurs’ perceptions that God or Allah causes violations when, for example, a customer absconds without paying for trade credit on goods already supplied |

Trade association | Industry or sector association specific norms determine what constitutes acceptable behaviour in the industry or association. For example, norms of payment of trade credit differ based on industry and association |

Relationships | The switching costs associated with particular relationships influence some entrepreneurs’ decision to continue working with existing partners who may default on credit payments Receiving benefits such as training on international standards, packaging, shipments, and fair trade branding influence some entrepreneurs to continue working with a partner in spite of breaches of contract terms |

Industry | The short shelf life and perishability of fresh agricultural products such as eggs and fresh vegetables influence some entrepreneurs to continue to supply their customers who may default on payments |

7.5 Outcomes of Trust Violations

Understanding the outcomes of trust violations is important to smaller businesses as they generally operate based on informal flexible agreements underpinned by trust. As stated earlier, trust violation is common in Ghana and in most cases the damage to businesses may be minimal. However in rare but extreme cases trust violation may lead to loss of resources, disappointment and grief, and misunderstanding which in turn may lead to the termination of a contract and relationship. This often happens when trust violations leads to substantial resource losses or when it is attributed to dishonesty. In extreme cases, trust violations may endanger the very existence of the firm (Bachmann 2001), and lead to serious financial, psychological, and social implications for the entrepreneur. It could also lead to a loss of interest in future collaborations by the victim and other entrepreneurs who may hear about the negative experiences of the victim.

Loss of Resources

Trust violations may lead to loss of resources including working capital, sales, and time. This happens in particular when entrepreneurs are over-reliant on specific customers or suppliers. For example, when a key customer violates a promise to buy from an SME, the business that has fallen victim may run into very serious liquidity problems that may threaten its survival. Similarly, supplier-related violations by a key supplier can threaten the survival of small businesses. For example, when partners supply poor-quality products that do not meet the specifications for customers, entrepreneurs may end up losing customers, market share, and destroying the brand in the long term. Trust breaches related to missing supply deadlines by suppliers can in turn lead to the loss of sales and possibly penalties based on clauses in MOUs and contracts. Another important resource that may be lost is time. The amount of time involved in seeking solutions after violations, and in repairing trust and building new relationships when relationships break down can be massive and may negatively impact on businesses since many entrepreneurs are time constrained.

Disappointment and Grief

Trust violations can also cause disappointment and grief to entrepreneurs especially when the betrayal was least expected and in circumstances where the loss is very damaging to the business. In such cases, entrepreneurs may experience painful emotions, self-blame, and uncertainty resulting from financial, psychological, and social costs. Particularly for smaller businesses, the entrepreneur as owner/manager and sole trader may be liable for the losses of his or her business (Bittker and Eustice 1994): hence a significant financial loss can be very traumatic. Similarly, due to the emotional relationship entrepreneurs have with their businesses (Shepherd 2003), the collapse of the business can also be very distressing. Psychological costs can also involve. entrepreneurs feeling ashamed and blaming themselves for lack of due diligence, sharing too much information, and for over trusting. Social costs can include negative impacts on relationships including marriages, families, and other social networks as well as loss of social status due to the embarrassment of being taken advantage of and often an inability to meet financial commitments to employees and other debtors in extreme cases of trust violations. Yet, researchers have paid little or no attention to disappointment and grief caused by breaches of trust in entrepreneurial relationships. The current focus is on the psychological, financial, and social costs associated with business failure (Shepherd 2003; Cope 2011), but not from trust violations.

Termination of Relationships and Loss of Interest in Future Collaborations

Trust violations involving substantial loss of resources often lead to a termination of relationships. In particularly if entrepreneurs perceive that the violations border on dishonesty and the perpetrator’s explanations of the causes of the violation are not deemed tangible This will be discussed in more details in Chap. 8. Negative experiences of trust violations may serve as a disincentive to some entrepreneurs in engaging in future collaborations. Negative experiences may also be shared among entrepreneurs, association members, family members, and communities, mainly by word-of-mouth, and this may discourage other entrepreneurs from engaging with the perpetrators whose reputation may be damaged. However, negative experiences can deter and cause other entrepreneurs who have heard about such experiences to be reluctant to engage in trust-based relationships with other parties, thus confirming existing studies on the negative outcomes of interorganisational trust violations on future trust relationships (Hardin 1996; Das and Teng 1998).

Case 7.2 Trust Violations and Outcomes

Kate is a postgraduate and an experienced entrepreneur who lived and worked in the EU but returned to Ghana in the early 1990s. She established a food processing company after recognising that there was plenty of seasonal fruit in the country during harvest times but fruits became very scarce during other seasons. She admits that as a small business, success to a large extent depends on building trust and relationships with customers, suppliers, and facilitators. However, she cautions that it is important not to trust partners too much. Her caution is based on her negative experiences of violations of trust by some customers and suppliers. Kate recounts two main incidents of trust violation that shaped her current attitude towards trusting her partners. At the early stages of her company she was able to secure an agreement to supply her products to one of the largest public institutions in Ghana. That customer was taking almost all her products, which enabled her company to grow very quickly and, due to the company’s limited capacity at that stage, she was not able to supply anybody else. After a couple of years of successful collaboration with the key customer, she run into a major problem when the government was changed and the state institution did not have the funds to pay her. Her company nearly ground to a halt and she had to secure finance from friends, family members, and banks to be able to start operating again. She also recounts another trust violation when a key supplier in the EU supplied junk machinery worth several tens of thousands of dollars to her. In spite of a signed agreement on the deal, the courts in Ghana could not assist her due to lack of jurisdiction since the perpetrator does not live in Ghana. Unfortunately, Kate could not seek redress abroad due to the fees for the courts and lawyers and the associated costs for hotel accommodation, visa fees, and air tickets. She ended up running into serious liquidity problems, laying off her staff, blaming herself, and vowing not to share too much information or trust any partner in future. Apart from the financial and marketing problems, Kate experienced serious emotional problems and grief. She lamented, ‘At that time my world fell apart, and I blame myself for trusting them. I lost everything—my working capital, couldn’t pay my staff, I was disappointed, embarrassed, and ashamed for not being able to pay and keep my hardworking staff. In fact, I fell ill for some days. But, I learnt a very important lesson. I will not give too much of my goods on credit, keep my eyes wide open in purchasing machinery and will not trust anybody’.

Anonymised case study from a respondent.

7.6 Conclusion

This chapter highlights how trust is violated in entrepreneurial relationships and the institutions and institutional logics that shape interpretations of trust violations. It also draws attention to the outcome of trust violations. The discussions show that trust violations are quite common in entrepreneurial relationships. Trust violations originate from the unmet expectations of actions and behaviour of partner entrepreneurs, managers and key boundary spanners of larger organisations, and state officials (Gillespie and Dietz 2009; Kramer and Lewicki 2010; Mitchell 1999). Customer-related violations range from customers delaying payments for goods supplied, giving excuses to justify not repaying trade credit, lying about the quality of products already supplied, lying about the time of depositing money in the bank, changing telephone numbers, and moving house to disappearing after receiving trade credit. Supplier-related violations involve supplying products/services late, supplying poor-quality products/services, diverting trade credit into other uses, and disappearing after receiving trade credit. Facilitator-related violations are based on allegations of corruption and nepotism by officials of state-sponsored enterprise-support institutions. The courts are also regarded as corrupt, expensive, and a waste of time due to cumbersome and long processes that are not friendly to entrepreneurs and SMEs. Allegations have also been made by association members against some trade association leaders regarding abuse of power, nonetheless, the trade associations are deemed more supportive and trusted than state institutions.

In spite of the occurrence and significance of trust violations in entrepreneurial relationships, the concept of trust violations remains unclear due to the logics of: culturally specific institutions, norms of relationships, and industry that shape interpretations of trust and trust violations in entrepreneurial relationships. The perceptions and interpretations of trust violations are specifically shaped by logics of weak legal institutions, family/kinship, religion, trade associations, and industry relations. Based on these institutional logics, some blatant incidents of trust violations are at times ignored or not acknowledged as trust violations. There are differences in perceptions of violations particularly between actors from different cultural backgrounds, associations, industries, and markets. It is therefore important for economic actors to understand the acceptable levels of trust violation in a relationship as this may vary between cultures, associations, sectors, and markets, and over time (Amoako and Lyon 2012). Due to the influences of these institutions and institutional logics, there is often a degree of acceptance about breaking integrity without violating perceived trust. Yet these logics have received very little empirical investigation in the literature.

This chapter also highlights that trust violations can lead to financial, psychological, and social costs. The outcomes of trust violations could have varying negative impacts on the entrepreneur and smaller businesses ranging from loss of resources, termination of relationships, near collapse of the business (Bachmann 2001), to disappointment and grief. The discussions show that when trust is violated, entrepreneurs and their firms may lose substantial resources including capital which, in extreme cases, can pose liquidity challenges. In cases where entrepreneurs may have suffered substantial financial loss, the disappointment can cause them painful emotions, self-blame, uncertainty, and grief. This happens to entrepreneurs owning smaller businesses due to the emotional relationship they have with their businesses (Shepherd 2003) in which the entrepreneur as a sole trader may also be liable for all the losses of the business (Bittker and Eustice 1994). This in turn may lead to loss of assets, feelings of shame, self-blame, and loss of trust in future collaborations. The time required to deal with the aftermath of the violations can also be significant. Entrepreneurs may spend time in an attempt to repair the relationship and, if unsuccessful, to build new relationships in order to gain access to the vital resources which may be lost as a result of the violation (Amoako 2012). There can be social costs as well; embarrassment can adversely impact on relationships including marriages and those with other social networks. The outcome of trust violations may also deter victims and their close networks from engaging in future collaborations. This may be explained by the role of word-of-mouth and second-hand information about the behaviour of perpetrators and the plight of victims of trust violations (Ajzen 1991). Yet the literature has only focused on the impact of trust violations on the firm rather than the entrepreneur.

This chapter contributes to the literature in four ways. First it presents a framework that attempts to integrate the role of the trustor, trustee, relationships, industry, and institutions in trust violations. Such an holistic view is lacking in the current literature. Second, it discusses the processes and provides examples of how trust is violated in entrepreneurial relationships in Africa. It thereby helps our understanding of how entrepreneurs owning and managing smaller businesses in Africa experience trust violations. Third, it draws attention to how the concept of trust violation remains unclear due to the logics of weak state and market institutions, culturally specific institutions, norms of relationships, and norms of industry that shape interpretations of trust and trust violations in entrepreneurial relationships. It therefore draws attention to the importance of economic actors understanding the acceptable levels of trust violations in a context and relationship as this may vary between cultures, associations, sectors, and markets—and over time. Fourth, it highlights that trust violations can lead to varying negative financial, psychological, and social costs to entrepreneurs. The discussions show that when trust is violated, entrepreneurs and their firms may lose substantial resources including capital, which in extreme cases can pose liquidity challenges. The disappointment caused by trust violations may result in painful emotions, self-blame, uncertainty, and grief to entrepreneurs and yet the literature has not paid attention to these negative impacts on the entrepreneur.