6.1 Introduction

Entrepreneurs owning and managing small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) do not normally have extensive resources at their disposal and this is especially the case in emerging economy contexts such as Africa where there is limited support from the state (Quartey et al. 2017; Etebefia and Akinkumi 2013). One promising means of ensuring access to resources is establishing cooperation in relationships with partners to bundle and create new and unique set of resources that can enhance the performance of both partners (Fink and Kessler 2010; Tesfom et al. 2004). However, entering into cooperative relationships entails risks as the performance of cooperating businesses becomes dependent on the future behaviour of the partner. In these relationships, mutual trust becomes an important coordinating mechanism that shapes the structure and performances of organisations (Vanneste 2016). As a coordination and control mechanism, trust reduces uncertainty by serving as a glue that holds relationships together and offering incentives for long-term cooperation (Altinay et al. 2014; Nooteboom et al. 1997; Deutsch et al. 2011).

Yet, trust is a very complex concept with diverse disciplines studying it based on divergent assumptions (Möllering 2006). The various disciplines often emphasise different elements of trust while paying less attention to the other equally important aspects. For example, psychology adopts behavioural approaches to trust. This approach focuses on internal cognitions of trustors and trustees, and observable choices of the trustor in interpersonal contexts based on rational expectation by referring to events produced by persons and impersonal agents (Lewicki et al. 2006), and thereby paying less attention to context. Similarly, mainstream economics focuses on the rational choice perspective and emphasises that rational actors are able to calculate and evaluate available alternatives and choose the best solution that optimises the decision maker’s utilities (Misztal 1996). Based on this approach, trust is regarded as based on reason, conscious and calculated (e.g. Gambetta 1988), and hence this perspective pays little attention to context. In contrast, the sociological approach focuses on institutions and social relations. Thus, this approach emphasises the role of culture cognition, norms, values, beliefs, and habits and routines (Zucker 1986; Möllering 2006). However, it underestimates the role of the trustor and trustee. Based on the above three perspectives, academics have regarded trust as an attribute based on internal cognitions including rational choice (Gambetta 1988), trust as routine and taken for granted (Zucker 1986), and trust as a reflexive process (Möllering 2006).

Due to the differences in theoretical approaches, there is no agreed definition of trust in the literature. However, Zucker (1986, 54) defines trust as ‘a set of expectations shared by all those involved in an exchange’. Zucker’s definition suggests that trust is both a state of mind developed by an individual through interaction with others and a reliance based on institutions (Bachmann and Inkpen 2011). Rousseau et al. (1998, 395) define trust as ‘a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the behaviour of another’. This definition recognises the cognitive rational and sociological habitual views of trust. The author draws on Zucker’s (1986) and Rousseau et al.’s (1998) definitions to develop a working definition of trust as; ‘a set of positive expectations that is shared by parties in an exchange that things and people will not fail them in spite of the possibility of being let down’. Section 6.2 explains the basis of this working definition.

Personal trust, organisational trust and institutional trust are further forms of trust. The integrity, ability and benevolence of the trustee forms the basis of the development of personal trust (Mayer et al. 1995). However, the development of organisational trust depends on trust in leaders or others in the organisation as well as on the reputations and brands (Zaheer et al. 1998), and institutional trust is based in and on institutions (Zucker 1986; Möllering 2006): see Chap. 3 for more details on the forms of trust.

The discussions in this chapter focus on trust development in entrepreneurial relationships in Africa, where there has been very little research on trust development. Even though during the past two decades there has been significant theoretical progress in trust research, there is a dominance of studies on trust development that draws mostly on Western institutional contexts where models, concepts, and measures emphasise the importance of trust based on psychological approaches and strong state and market institutions and legal contracts (see Mayer et al. 1995; Zaheer et al. 1998). Compared to Western contexts, researchers have not given much attention to trust development in emerging economy contexts where state and market institutions are weak. In emerging economy contexts, there are weak legal systems, weak contract enforcement, and hence limited institutional trust. Yet, emerging economies such as China, India, the Philippines, Brazil, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Ghana have witnessed increased entrepreneurship and rapid economic growth (PWc 2017). In these economies, entrepreneurs develop trust in less formal (parallel) institutions such as networks, trade associations, and religions. Hence, informal cultural institutions provide the basis of trust (see Amoako and Lyon 2014; Welter et al. 2005, Wu et al. 2014). However, there is little knowledge about how the logics of informal cultural institutions shape trust development processes in entrepreneurial relationships in emerging economies including Africa (Wu et al. 2014; Amoako and Lyon 2014; Li 2016).

Another major limitation relating to discussions on SMEs interorganisational trust development in African and Ghanaian contexts relates to limited knowledge about how trust is developed. While in larger organisations, personal trust enhances interorganisational trust through the attitudes, characteristics, and actions of boundary spanners (Zaheer et al. 1998; Vanneste 2016), in SMEs in Ghanaian and African contexts, the distinction between interorganisational trust and interpersonal trust is more complex and unclear. This is due to the smaller sizes of SMEs and also to the high power distance in African cultures, as a result of which entrepreneurs owning and managing smaller businesses remain key decision makers and key boundary spanners for their organisations (Kuada and Thomsen 2005). Consequently, it is difficult to differentiate between trust in partner SMEs and trust in entrepreneurs who own and manage those businesses (Amoako 2012). As a result, interorganisational trust in entrepreneurial relationships with SMEs tends to be more personal. The entrepreneurs (trustees) owning and managing SMEs base trustworthiness in these firms on the characteristics, behaviour, actions, and interactions with partner entrepreneurs (Zucker 1986; Mayer et al. 1995; Möllering 2006). This may differ in larger organisational contexts where the number of employees is higher and a number of managers engage in decision making. It may also differ in other economies and contexts where there is less power distance and SMEs may have larger numbers of employees (Rousseau et al. 1998). Yet, the literature has not paid much attention to these differences.

This chapter aims to address these gaps by examining how state and market institutions as well as cultural institutions influence the processes of trust development in Ghana. It also explores how entrepreneurs owning and managing SMEs develop personal/organisational trust in entrepreneurial relationships. Given that Africa is a vast continent that has many national and distinct institutions, cultures, and sub-cultures, the current discussions and analysis of trust development in this chapter will be based on the literature and an empirical study in Ghana (see Chap. 1 for details on methodology). This approach aims to enhance an in-depth understanding of how entrepreneurs draw on logics of societal institutional orders such as weak legal systems, and cultural institutional orders such as family/kinship, trade associations, and religion in trust development processes in an African context.

The literature suggests that actors use institutional logics to interpret and make sense of the world although not always consciously to support networking and trusting behaviour, while at the same time actors’ networking and trusting practices and behaviour can both reinforce and challenge the assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules considered appropriate in a particular sphere of social life (see Besharov and Smith 2014). Hence, institutional logics offer strategic resources that connect organisations’ strategy and decision making (see Durand et al. 2013). Throughout this book, the author argues that entrepreneurs in Africa as actors use logics to interpret and make sense of the contexts, not always consciously, to support networking and trusting behaviour, while at the same time actors’ networking and trusting practices and behaviour can both reinforce and challenge the assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules considered appropriate in a particular sphere of social life (see Chap. 1). In this Part III (covering Chaps. 6, 7 and 8), the author examines how societal-level logics of state and indigenous cultural institutions and norms underpin entrepreneur’s decisions to develop trust, interpret trust violations, and repair trust.

The investigations and discussions in this chapter focus on the following questions: (1) ‘What are the institutions that shape trust development?’ (2) ‘How do entrepreneurs perceive trustworthiness and what are the forms of trust developed?’ (3) ‘What are the outcomes of interorganisational trust?’

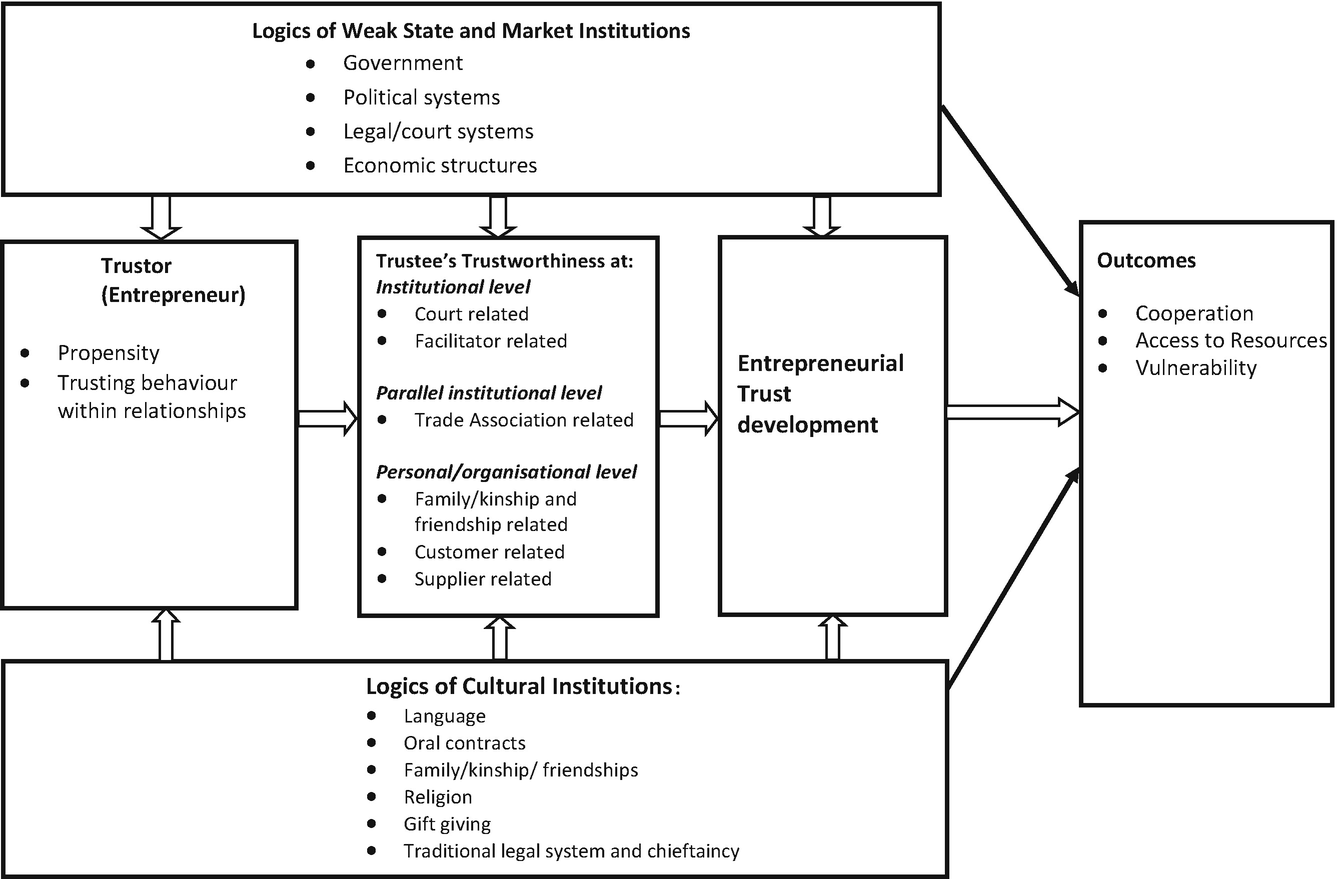

Entrepreneurial trust development in weak institutional contexts. (Source: Own research)

This chapter contributes to the literature by first, presenting a framework that visualises a holistic approach to trust development in SME interorganisational relationships in an emerging economy (and African) context based on the entrepreneur (trustor), his or her trading partner (trustee), their relationship, and the external cultural norms that shape the trust processes within relationships. Second, reconceptualising the role of state and market institutions and identifying cultural-specific institutions that provide the logics that enhance trust development in entrepreneurial relationships in an African context. Third, showing how personal/interorganisational trust comingles in the SME context due to the dominant role of the entrepreneur who as an actor develops trust in relationships to mitigate institutional weaknesses in Ghana. Fourth showing how as actors entrepreneurs do not necessarily yield to formal institutional constraints but respond by relying on alternative indigenous institutions.

The rest of this chapter is structured as follows. Section 6.2 analyses the contexts focusing on the logics of institutions and relationships that shape trust development in Ghana. Section 6.3 discusses the entrepreneur as an actor—propensity to trust and trusting behviour. Section 6.4 examines trustee’s trustworthiness and forms of trust developed in entrepreneurial relationships. Section 6.5 describes trust outcomes and Sect. 6.6 concludes the chapter.

6.2 Ghana: Logics of State, Market and Cultural Institutions Shaping Trust Development

Like some African countries, the British colonial administration created Ghana. Ghana is located on the Atlantic Coast of West Africa and shares borders with Togo to the east, Cote D’Ivoire to the west, and Burkina Faso to the north, and currently has a population of about 29.6 million (Ghanaian Times 2018).

6.2.1 Logics of Government, Political, Legal, and Economic Institutions

During the immediate years after independence in 1957, the state adopted protectionist trade policies and institutions dominated by state-owned enterprises. Based on this ideology, state institutions and the public sector received priority while the domestic indigenous sector and entrepreneurial class were regarded as a threat to the political system and was not encouraged (Kayanula and Quartey 2000). State-led development persisted until 1983 by which time the economy had nearly collapsed (Nowak et al. 1996). The country also experienced political turmoil from military takeovers between 1966 and 1982. During this era and beyond, the military and political system often accused entrepreneurs of kalabule or profiteering and the harassment, interference, bureaucracy, and corruption from the military and government officials constrained the growth of entrepreneurship and SMEs (see Buame 1996; Ninsin 1989). Nonetheless, since 1992, Ghana has practised multi-party democracy characterised by freedom of speech and a vibrant press. As a result, the country enjoys high levels of social capital.

Between 1970 and 1985, some attempts were made to stimulate entrepreneurship through a number of policies and the establishment of state institutions. For example, in 1970 the government enacted the Ghanaian Business Promotion Act (Act 334) to facilitate entrepreneurship and small business development (Ninsin 1989). Furthermore, in 1985 the government established the National Board for Small Scale Industry (NBSSI) based on Act 434 of 1981 to serve as the government institution responsible for the promotion and development of micro and small enterprises (MSEs) primarily in the informal sector. However, the policies are scattered around several government ministries and institutions that rarely interact with each other.

Nonetheless, since the year 2000, there has been a number of initiatives to address these constraints. For example, in 2017 the government launched the Ministry of Business Development to champion entrepreneurship in Ghana. The flagship programme of this ministry is the National Entrepreneurship and Innovation Plan (NEIP). NEIP has an initial seed capital of $10 million that will be increased to $100 million through private sector development partners. The capacity-building project aims to equip the youth with entrepreneurial skills and to enhance start-ups, business growth, and economic development.

British Common Law underpins the legal/court systems in Ghana and yet traditionally Ghana’s legal/court system does not pay much attention to private sector and enterprise development. Primarily, the laws and regulations enacted by formal institutions are not targeted at entrepreneurship and so the system is expensive, time consuming, and corrupt all of which constrain institutional trust and this will be explored further in Sect. 6.4.1.

Nonetheless, Ghana is one of the African countries that has achieved remarkable economic growth since 2000. Currently, Ghana is a lower middle-income country with gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of US $ 1632 (GSS 2018). In 2018, Ghana was one of the world’s fastest-growing economies with projected growth between 8.3% and 8.9% (New York Times 2018). However, interest rates and inflation still remain relatively high at 20% and 10.6% year on year in 2018 (Trading Economics 2018), so the cost of finance for entrepreneurship still remains very high.

Yet, many businesses have sprung up, and as in most Africa countries, the majority of businesses (62%) are SMEs operating in the informal sector that is composed of unregistered firms offering wage employment in unregulated and unprotected jobs. Informal businesses used to employ over 90% of the total workforce (World Bank 2004; GSS 2010). The Ghana Statistical Service defines an informal business as a business that does not have professionals keeping its accounting records (GSS 2016) and therefore mostly operating outside the tax net. Yet, this definition is contestable as the overwhelming majority of businesses in the sector operating in the open markets and in the streets pay various forms of taxes to local government tax officials. SMEs dominate the three main sectors of the economy: agriculture (19.5%), manufacturing (24%), and services (56.4%) (CIA World Factbook 2016). Therefore, Ghanaians respect entrepreneurs and regard starting and managing an SME as a good career choice in the country.

However, there is no single definition of SMEs in Ghana (Teal 2002). Hence, for practical application, this study adopts the definition of SMEs from the Ministry of Local Government based on the number of people employed: micro having 1 to 5 employees, small having 6 to 29, medium having 30 to 100, and large more than 100. The analysis of trust development, trust violations, and trust repair in Part III of this book therefore focuses on the businesses employing 100 or fewer people and operating in agricultural, services, and manufacturing sectors of the economy.

6.2.2 Logics of Cultural Institutions Shaping Trust Development

In domestic and West African markets, entrepreneurs refer to logics of cultural-specific norms and indigenous institutions in entrepreneurial relationships with customers, suppliers, and facilitators showing how personal/organisational trust and relationships are embedded in existing social structures. The logics of language, oral contracts, family/kinship and friendships, religion, punctuality, gift giving, and chieftaincy underpin trust development and the management of relationships.

6.2.3 Logics of Language Shaping Personal/Organisational Trust

One of the key influences on personal/organisational trust is language and yet researchers have paid very little attention to how different languages conceptualise trust (Lyon et al. 2012). In Ghana, Akan/Twi which is spoken by nearly half (47.5%) of the population (GSS 2010), conceptualises trust as gyedie, ahotosoo, or twere. Gyedie means ‘belief or faith’, ahotosoo means ‘reliability and dependability’, and twere (a verb) literally means ‘to lean on’ (Amoako 2012). Entrepreneurs often lean on relationships with key partners to grow their businesses. Whilst gyedie (faith or belief) describes the psychological state of the actor (trustor), ahotosoo (reliability or dependability) is similar to both ability and integrity of exchange partners (Mayer et al. 1995). Leanability (twere or to lean on) suggests that the entrepreneur expects the partner (trustee) to willingly support the entrepreneur (trustor) and so highlights the norms and expectations to be fulfilled by the trustee. However, twere (to lean on) has received less attention in the literature. ‘Leanability’ as a trust expectation, suggests stronger elements of obligation between relationship partners. This could be related to the norms of the Akan and African family systems that oblige members to remain loyal to and support each other. Hence, trust in the Akan context of Ghana may often be based on stronger expectations and obligations than in Western cultures where there are less obligations in the family system (Amoako 2012).

Therefore, in this book, the meaning of trust in Akan/Twi (gyedie, ahotosoo, and twere) which emphasises the trustor’s faith or belief, reliability, expectations, and vulnerability provides a working definition. As stated in Sect. 6.1, the author defines trust as; ‘a set of positive expectations that is shared by parties in an exchange that things and people will not fail them in spite of the possibility of being let down’. This definition focuses on personal/organisational trust and institutional trust. These forms of trust are embedded in oral contracts; a key, culturally specific institution that facilitates entrepreneurial relationship development.

6.2.4 Logics of Oral Contracts Shaping Personal/Organisational Trust Development

Entrepreneurs trading in Ghana and in other African countries rely on personal/organisational trust based on oral contracts. This is contrary to advanced economies where entrepreneurs rely mainly on institutional trust based on written contracts and less on personalised trust (Welter and Smallbone 2006; Welter et al. 2005). Amoako (2012) defines a written contract as ‘a written agreement between exchange partners prepared by a lawyer with clauses that ensure that exchange partners are accountable and liable in case of non-compliance’.

Entrepreneurs use oral contracts within entrepreneurial customer and supplier relationships during face-to-face meetings and telephone conversations. However, occasionally, they may write agreements on pieces of paper in the presence of other traders or family members and friends who may serve as witnesses. Entrepreneurs use trust in personal relationships and social norms to enforce these oral contracts and sanction defaulters. These measures are relatively effective as, in most relationships, partners do not renege on their obligations.

Nevertheless, a few entrepreneurs rely on a memorandum of understanding (MOU) and even fewer on written contracts in their relationships, particularly in international markets. These entrepreneurs are mostly exporting to Western countries and other markets outside of Africa. That said, it is important to emphasise that the entrepreneurs using contracts understand that personal relationships based on trust remain very important as day-to-day relationship management depends a lot on personal trust. This is understandable since covering all expectations in a contract is practically impossible (Arrow 1974).

Ghanaian entrepreneurs’ reliance on personal trust could be attributed to the relatively weak enforcement and sanctioning mechanisms imposed by legal systems (Amoako and Lyon 2014). However, it is also important to emphasise that norms of contracts were also part of the colonial institutions exported by the British colonial administration that are yet to be assimilated into the social and business norms of smaller businesses which have historically relied on trust in personal networks to do business.

6.2.5 Logics of Family/Kinship and Friendship Shaping Personal/Organisational Trust Development

The British carved out Ghana without recourse to ethnic affinity even though kinship ties underpin the socio-cultural structures of all ethnic groups. Ghana is a multiethnic and multicultural country. There are about 92 different ethnic groups usually classified into a few larger groups: Akan (47.5%), Mole Dagbani (16.6%), Ewe (13.9%), Ga Adangbe (7.4%), Geme (Gurma) (5.7%), Guan (3.7%), Grusi (2.5%), Mande Busanga (1.1%), and others (1.4%) (Ghana Statistical Service 2010). These different ethnic groups are, in most instances, mixed and scattered in the 10 regions in the country and with the exception of a few ethnic conflicts in the north of the country, the various groups coexist peacefully.

Within the ethnic groups, individuals have a close network of ties through family members, extended family members, community, tribe, and/or ethnicity (Gambetta 1988). The extended family develops the norms, values, and behaviour that society regards as acceptable. Individuals, as a result, have extended rights as well as extended obligations (Acquaah 2008; Amoako and Lyon 2014).

In the context of entrepreneurship, the literature posits that norms of family/kinship/friendship emphasise loyalty based on emotion, caring, and sharing and as a result can enhance the competitiveness of a business through decision making, strategic planning, and motivating family members and employees to work harder. A family can particularly bring clear values, beliefs, and a focused direction into the business (Burns 2016; Tokarczyk et al. 2007; Aronoff and Ward 2000). Family norms can further enhance SME internationalisation based on trust in family ties (Oviatt and McDougall 2005). Nevertheless, family values can also bring a lack of professionalism, nepotism instead of meritocracy, rigidity, and family conflict into the workplace (Schulze et al. 2001; Miller et al. 2009; Burns 2016).

In Ghana, family networks may provide access to suppliers, customers, and start-up capital and may also allow entrepreneurs to hire less-qualified family members—and yet the hiring of unqualified family members may hamper innovation (Robson and Obeng 2008). The empirical study reveals that norms of family also enable entrepreneurs to develop trust in relationships with customers, suppliers, and facilitators. Furthermore, trust development processes in entrepreneurial relationships draw on logics of family/kinship such as reciprocity, caring, and support of members to help cement relationships. Again, entrepreneurs’ trust propensity is influenced by norms of family that lead to the development of positive attitudes towards partners they regard or who regard them as family members rather than business partners. Interestingly, the norms of the Akan family system make it morally wrong to abandon a ‘brother’, ‘sister’, or family member. This may explain why, on some occasions, some entrepreneurs are stuck in relationships that may not be very beneficial. In such cases, they need repeated evidence of untrustworthy behaviour to change their initial trust levels (Bachmann and Zaheer 2013).

Entrepreneurs also draw on the logics of family to enforce contract agreements within entrepreneurial relationships in the midst of weak and corrupt legal systems (Amoako 2012). The contract enforcement process involves the use of the traditional judiciary system that initially starts with family elders and can be escalated to the chief, paramount chief, or king only if the elders fail to find a solution (Myers 1992; Osei-Hwedie and Rankopo 2012).

Yet, the logics of family may constrain the development of entrepreneurship by limiting the ability of married females to independently establish and manage their own businesses. For those who manage to do so, the development of trust in entrepreneurial relationships is often constrained due to norms of family that disallow females to ‘sit’ and have conversations or establish close relationships with men who are not their husbands (Amoako and Matlay 2015). This is customarily common in some parts of the north of the country where Islam deeply influences family norms. Amoako and Lyon (2014) have dubbed the contradictory roles of family/kinship as ‘the paradox of the family’. Throughout Africa, patriarchal family/kinship systems in most cultures constrain women’s businesses (see Chap. 4).

6.2.6 Logics of Religion Shaping Personal/Organisational Trust Development

Logics of religion shape the psychological state, the entrepreneurial networks (Vinten 2000; Drakopoulou Dodd and Gotsis 2007; Dana 2010), and the trust building of entrepreneurs (Amoako and Matlay 2015). Nevertheless, the relationship between religion and entrepreneurship remains complex (Drakopoulou Dodd and Seaman 1998).

Religion is a very important cultural factor in Ghana. The population is composed of about 71.2% Christians, 17.6% Muslims, and about 5.2% Animists and those not affiliated to any religion is 5.3% (Ghana Statistical Service 2010). Islam remains the dominant religion in some parts of the northern regions of the country whilst Christianity is the dominant religion in the south of the country. This is due to historical influences based on trading links with Arabs and Europeans. While Arabs (Muslim) merchants focused their activities in the north, European merchants (mostly Christians) settled in the south (coast) of the country during the colonial era.

Religious norms of fairness, reciprocity, and ‘brotherliness’ all promote trust building between partners in Ghana and in West African markets (Amoako and Lyon 2014; Amoako and Matlay 2015). Religion also promotes trust development in the entrepreneurial relationships of Ghanaian internationally trading SMEs based on shared beliefs, values, and faith. Entrepreneurs often refer to God-fearing people as being trustworthy as those partners often abide by contract agreements. Hence, religious norms influence entrepreneurs’ trust propensity by leading to the development of more positive attitudes and higher disposition to trust which make them less suspicious of partners (Bachmann and Zaheer 2013), particularly those who share their religion. Logics of religion facilitate advancing trade credit to partners, especially fellow believers. Logics of religion also facilitate enforcement of agreements and in cases of default, entrepreneurs may resort to mediation through prayer, religious leaders (pastors, imams, akomfoo, and deities) to enforce trade agreements (Amoako 2012). Furthermore, logics of superstition and fatalism from Christianity, Islam, and traditional African religions may all enhance trust development and conflict resolution due to their inherent moral beliefs that restrain followers from opportunism. However, entrepreneurs may also invoke God, Allah, or traditional gods to sanction (curse) customers, suppliers and facilitators who refuse to fulfil their contractual obligations in relationships. The use of logics of religion shows how actors may internalise norms and thereby behave morally to avoid guilt and shame in economic exchanges (Platteau 1994). However, due to logics of fatalism, at times entrepreneurs who hold fatalistic beliefs accept vulnerability in their relationships (Amoako and Matlay 2015). Furthermore, fake religious leaders may violate trust and exploit entrepreneurs (see Chaps. 4 and 5). However, religion has less impact on entrepreneurial relationships in international markets.

6.2.7 Logics of Gift Giving Shaping Personal/Organisational Trust Development

The practice of giving gifts to business partners is a norm in the development of trust and management of entrepreneurial relationships in Africa (see Chaps. 4 and 5 and Yanga and Amoako 2013). Gift giving enhances favours, obligations, and reciprocity among African communities and thereby fosters peaceful coexistence (Kenyatta 1965). Without exception, Ghanaian entrepreneurs sometimes offer gifts to and/or receive gifts from their business partners. The gifts include small amounts of cash, food items, toiletries, clothing, jewellery, and many other items. As stated in Chap. 5, even though gifts may be given to business partners throughout the year, they may be particularly given during festive occasions such as Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha (Islamic holidays), Christmas, and New Year. Entrepreneurs also at times offer gifts to other stakeholders such as family members of their trading partners, traditional chiefs, religious leaders, community leaders, and officials in state institutions. In her study of trust development among yam and cassava traders in Ghana, Lassen (2016) confirms that gift giving is an integral part of cementing trading relationships in Ghana.

Yet, some Ghanaian entrepreneurs insist that gift giving to officials of state institutions is contentious since it can perpetuate corruption. As a result, they do business with government officials without giving gifts, while others concede that at times they offer gifts in order to obtain assistance from state officials, some of who may not perform their duties because they do not receive gifts. However, as stated in Chap. 4, the request for and giving of gifts to state officials raises ethical concerns relating to the perpetuation of corruption and needs to be examined thoroughly to enhance accountability of state officials in Ghana and other African countries.

6.2.8 Logics of Traditional Legal Systems and Chieftaincy Shaping Trade Associations and Parallel Institutional Trust Development

Trust in trade associations is partly due to the ability of trade associations to mediate in disputes between entrepreneurs and their trading partners in local and West African markets. The associations run parallel to state institutions and play a critical role in contract enforcement. However, most associations adopt conflict resolution structures from indigenous, traditional chieftaincy and justice systems. For example, among the food trading and exporting sectors with predominantly female entrepreneurs, in the Akan areas of Ghana, the leader of a trade association in the open markets often has the title of ohemma, which is the traditional chieftaincy title for the queen and is linked with the name of a particular commodity, such yam (bayere). Hence, the title of the leader of the yam trade association is bayere hemma (literally yam queen). Similarly, the title of the leader of the orange sellers association is known as ankaa hemma (literally orange queen). The ohemma has a secretary who, although acting like a spokesperson, also controls access to the queen. This role also reflects the role of the okyeame-traditional linguist, the spokesperson for the traditional chief. The use of the English word ‘secretary’ in the Twi/Akan language reflects the hybridisation of Western corporate and cooperative norms in Ghana. The powerful trade associations are those that have the endorsement of traditional rulers and local government officials and, as a result, have the backing of authorities at the grassroots level. In this way, norms of chieftaincy enable trade associations to serve as important institutions parallel to the courts, which are perceived to be corrupt, expensive, and a waste of time (Amoako and Lyon 2014; Amoako and Matlay 2015).

Similarly, the indigenous efiewura (landlord) system dominating the trade associations operating in the food export sector in Ghanaian and West African markets is embedded in industry-specific trade associations operating in the open markets in West African markets. Entrepreneurs trading in agricultural goods, particularly food, in West African markets often accompany their goods to export destinations and wait to collect their money from their customers (efiewuranom) when they have finished selling the produce.

Logics of traditional institutions such as chieftaincy, in various ways, help to reduce uncertainty and enhance entrepreneurship in Ghana and West Africa. However, norms of chieftaincy can also constrain entrepreneurship. For example, chiefs can prevent entrepreneurs from getting land when the ruler disagrees with what they want to do or feels threatened by the activities of the entrepreneur.

6.3 The Entrepreneur as Trustor: Propensity to Trust and Trusting Behaviour Within Relationships

Ghanaian entrepreneurs owning and managing internationally trading SMEs, as actors, play dominant roles in the development of interorganisational trust. Even though there are examples of other staff being involved in the process, the entrepreneur remains the key decision maker in trust development. Entrepreneurs’ propensity or readiness to trust and expectations about the trustworthiness of partners in relationships shape their trusting behaviour and trust development in SME interorganisational relationships (Rotter 1967; Mayer et al. 1995; Tanis and Postmes 2005).

Apart from family/kinship and friendships, entrepreneurs rely on relationships with customers (who could be intermediaries or agents) and suppliers in local, West African, and international markets. Reciprocity and mutuality between organisations and between individuals in each organisation form the basis of these relationships (Zaheer et al. 1998; Vanneste 2016). However, there is a distinction between cross-cultural relationships with West African partners where there is evidence of personal trust based on oral contracts, social relationships, and other common norms related to doing business in the region, and those in intercontinental relationships outside of Africa where norms of contracts and memorandums of understanding are more common.

In local and West African markets, entrepreneurs embark on visits to business places and homes to meet employees, family members, and at times community leaders to reinforce their relationships. Entrepreneurs also use indigenous institutions such as gift giving and social events such as weddings and funerals to cement relationships. In distant local and West African regional markets, to be successful, entrepreneurs trading in agricultural produce rely on relationships with efiewuranom or commission agents in neighbouring countries such as Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali. Entrepreneurs offer their goods on credit to the efiewuranom or agents who take delivery of the goods and sell them for a commission. The process can last from a few days to a few weeks. These agents serve as intermediaries who shrink the psychic distance between exporters and the markets of their choice. Personalised trust and parallel institutional trust in trade associations rather than formal contracts or memorandums of understanding underpin relationships within the traditional system. The relationships are often reinforced through common languages, religious beliefs, the sharing of information, and at times the provision of accommodation for the agents in distant, regional, West African markets (Amoako and Lyon 2014; Amoako and Matlay 2015).

In contrast, in intercontinental trade with customers abroad—mainly in the European Union, Asia, the United States, and Canada—entrepreneurs often rely on institutional trust in the form of written agreements, primarily memorandums of understanding and a few formal legal contracts. As a result, most entrepreneurs use written purchase orders when operating outside Africa. However, entrepreneurs encounter challenges in enforcing these contracts in Ghana since the courts lack jurisdiction in cases involving partners who do not reside in Ghana.

Apart from customers and suppliers, about half of the entrepreneurs operating in the formal sector collaborate with enterprise facilitators funded by the state or international donors. The various facilitators play diverse roles in assisting entrepreneurs to acquire skills in finance, market information, marketing, and networks. However, all the entrepreneurs belong to trade associations that can be conceptualised as forms of institutional-based trust with these less-formal institutions operating in parallel to the state institutions. The trade associations play a crucial role in trust development and in promoting international business through offering crucial services to entrepreneurs, as will be discussed later in this chapter.

6.4 Trustees’ Trustworthiness and Forms of Trust Developed in Entrepreneurial Relationships

Trustworthiness refers to the behaviour and actions of trustees that will lead them to be more or less trusted by the trustor (Mayer et al. 1995; Rousseau et al. 1998). These actions and behaviour form the basis on which the trustor becomes willing to be vulnerable. In entrepreneurial relationships with SMEs in Ghana, the actions and behaviour of the partner entrepreneur forms the basis of trustworthiness. However, in relationships with larger organisations, the actions and behaviour of managers who serve as key boundary spanners determine trustworthiness even though there is evidence that the characteristics and reputation of the firm also count for some entrepreneurs (Zaheer et al. 1998; Gillespie and Dietz 2009). Similarly, the actions and behaviour of key boundary spanners and officials of state institutions also determine the trustworthiness of institutions (Mitchell 1999). Hence, entrepreneurs perceive trustworthiness at the institutional level, parallel institutional level, and personal/organisational level. While the literature suggests that entrepreneurs rely on personal trust, organisational trust, and institutional trust (see Chap. 3), in the empirical study, the evidence shows that Ghanaian entrepreneurs do not often differentiate between the entrepreneurs who own and manage partner SMEs and their firms, in terms of trustworthiness. As a result, personal trust and organisational trust are not distinct but rather form a mixture with each substituting for or complementing the other at different times within the working relationships of the entrepreneur.

6.4.1 Trustworthiness at the Institutional Level

Institutional trust refers to trust within and among institutions as well as the trust individuals have in those institutions (Möllering 2006). Institutional trust allows relationships to develop based on expectations that all parties will observe legal systems and common norms (Zucker 1986). However, entrepreneurs in Ghana have limited institutional trust in the courts and state-backed enterprise support institutions due to widespread allegations of bribery and corruption (Amoako 2012; Damoah et al. 2018).

Trustworthiness in institutions relates to the degree to which the behaviour of officials of enterprise support institutions is consistent with the rules, regulations, and objectives of those institutions (Mitchell 1999). The character, actions, and behaviour of officials and key boundary spanners shape the level of trust and the reputation of institutions (Mayer et al. 1995; Zaheer et al. 1998; Gillespie and Dietz 2009).

To entrepreneurs, honesty of officials remains the most important expectation that determines the trustworthiness of state and market institutions. Honest officials refer to those who are not corrupt and provide services to entrepreneurs without asking for bribes and favours. One of the key institutions whose officials and effectiveness influence institutional trust is the legal/court system in any country (Zucker 1986). Yet, Ghanaian internationally trading entrepreneurs generally do not use the courts due to widespread allegations of corruption by officials, delays due to long and cumbersome processes, and high costs. Similarly, perceptions of delays due to long processes and corruption prevent entrepreneurs from using the courts in West African markets. Entrepreneurs exporting to international markets also perceive the legal systems to be inaccessible and unaffordable (Amoako and Lyon 2014; Amoako 2012). Due to these barriers, there is lack of trust in the courts.

Furthermore, entrepreneurs link the lack of institutional trust to the level of limited support from state institutions that are meant to facilitate entrepreneurship. State institutions provide limited support to entrepreneurs in the formal sector regarding financial assistance from banks, market information, and training. However, those operating in the informal sector do not receive support from the government even though the sector employs over 90% of the total workforce (World Bank 2004; GSS 2010). Previously there was distrust due to suspicion and harassment from both local and central government officials involved with the collection of taxes from entrepreneurs (Palmer 2004). Nevertheless, currently, due to government’s emphasis on entrepreneurship, and the fight against corruption there seems to be an upsurge of trust in the prospects for entrepreneurship and small businesses in the country. For example, in 2017 the government passed a bill setting up the Office of the Special Prosecutor to combat corruption in the country. The Special Prosecutor has a mandate to investigate and prosecute cases of alleged corruption-related offenses involving political office holders, public officers, and their accomplices.

Some entrepreneurs operating in the formal sector develop trust in donor agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that support enterprise development in Ghana. These organisations include the British Council, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA), and Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ), and NGOs. Trustworthiness of these institutions relates to the actions and behaviour of officials of these organisations as well as the nature of the services provided to entrepreneurs. The services provided include training, finance, market information, and networking. While these institutions may not be corrupt, their services are mainly limited to highly educated entrepreneurs operating in the formal sector (Amoako 2012) and so entrepreneurs in the informal sector do not trust them.

In the midst of limited support and trust in state and market institutions, entrepreneurs in Ghana rely on trust in alternative indigenous institutions, such as trade associations, to develop parallel institutional trust in order to enhance their activities (Amoako and Lyon 2014).

6.4.2 Trustworthiness at the Parallel Institutional Level

The author defines parallel institutional trust as ‘trust in local cultural institutions that run side-by-side [with] state institutions to facilitate entrepreneurship’ (Amoako 2012). Notably, trade associations provide parallel institutional trust based on their stock of social capital and the selective incentives they provide to their members (Ville 2007; Reveley 2012). Hence, all the internationally trading entrepreneurs involved in this study are members of trade associations.

Trade associations and trust development in Ghanaian and West African markets

Trust expectation | Association activities underpinning trust expectation |

|---|---|

Regulation | Controlling access to market spaces in local open markets Setting prices and controlling supplies to local open markets |

Conflict resolution | Resolving and mediating in conflicts and disputes between members and between members and their trading partners Sanctioning members who may blatantly abuse general norms of the association and/or their obligations to trading partners |

Advocacy | Representing members Liaising with traditional rulers, and national and local governments on matters such as taxes and market spaces Liaising with external bodies such as other associations and NGOs |

Legitimacy | Ensuring the activities of businesses in the industry are lawful and socially acceptable |

Networking | Organising meetings and functions that facilitate friendships, cooperation, and learning |

Sharing market information | Providing information about market opportunities and risks |

Reference for reputation and creditworthiness | Providing information about members’ traceability and creditworthiness to potential customers in domestic and international markets |

Skills development | Building the skills of members through training programmes on management, standards, and specifications |

Welfare | Providing welfare to members through donations during ill health and other issues to help sustain the working capital of members Providing informal forms of insurance to members in extreme cases |

As shown in Table 6.1, trade associations offer important services and are unique in defining norms, regulating industries, resolving conflicts, and offering many other critical services to entrepreneurs. These capabilities relate to the unique structures of associations that, in some cases, are a hybrid of the traditional chieftaincy model and Western corporate or cooperative management styles (Amoako and Lyon 2014). Yet, Ghana and other African states and international donor agencies rarely fund trade associations, and those that are funded are not encouraged to build on their existing indigenous practices but instead they are required to conform to imported Western norms which often may not be fit for purpose (Amoako and Lyon 2014).

Case 6.1 Trade Association Leader and Parallel Institutional Trust in Ghana

Obiri is an entrepreneur who exports about 70% of his fresh oranges to distant markets in Northern Ghana, Burkina Faso, and Niger. He founded his company in 1985 and operates from Techiman Market in the Brong Ahafo region of Ghana. He has not registered his company with the Registrar General, but instead he operates in the informal sector under the umbrella of a cooperative—the Orange and Fruit Sellers Association. Obiri is a founding member of the association and has served as the secretary and okyeame to the chairperson, the ankaa hemma (orange queen) for more than 20 years. As the secretary and okyeame, he serves as the spokesperson or linguist who in the traditional chieftaincy model serves as a gatekeeper to the traditional chief. Together with the chairperson, they transformed the association into a vibrant export network that works closely with entrepreneurs, trade associations and agents (efiewuranom) in distant markets in Northern Ghana and neighbouring countries in West Africa. Additionally, as the secretary he liaises with the ohemma to regulate prices in the local market and works with the local chiefs and government officials to provide advocacy and legitimacy to members. Obiri is also involved in the provision of market information, networking, references regarding reputation and creditworthiness of members, as well as welfare to needy members. One of his key roles is to help resolve conflicts among members of the association and between members and their customers and suppliers. Through these activities, Obiri and the ohemma, as leaders of the trade association provide parallel institutional trust that allows the orange and fruit sellers to operate across local, distant, and neighbouring West African markets without much support from state and market institutions.

6.4.3 Trustworthiness at the Personal/Organisational Level

As stated at the beginning of this section, trustworthiness at the personal/organisational level is linked mainly to the behaviour and actions of entrepreneurs and managers of partner firms that lead them to be more or less trusted by the entrepreneur (Mayer et al. 1995; Rousseau et al. 1998). Yet organisational factors like reputation can also form the basis of personal/organisational trust. Entrepreneurs base these behavioural dimensions more on rationality as they often calculate the risks involved in trusting. This study uncovers that, while the literature on buyer-supplier relationships refers to trust within buyer-supplier relationships (e.g. Smith et al. 1995), trustworthiness and trust expectations in customer relationships differ from those in supplier relationships. Hence, here, trust developments in the two entrepreneurial relationships are distinct and discussed separately.

6.4.4 Trustworthiness in Family/Kinship and Friendships

The logics of family/kinship and friendships underpin trust development in Ghana. Trustworthiness in family/kinship and friendship in entrepreneurship relates to the development of personalised relationships based on logics of family/kinship such as reciprocity, caring, and support of members to help cement relationships. The norms of the Akan family system make it morally wrong to abandon a ‘brother’, ‘sister’, or other family member. (See Sect. 6.2.5 for more details on family/kinship and friendship and trust development.)

6.4.5 Trustworthiness in Working Relationships

While, the literature refers to trust within buyer-supplier relationships (Smith et al. 1995), in this study, it is shown that trustworthiness and trust expectations in customer and supplier relationships are different: hence the two concepts are referred to as customer-related trust and supplier-related trust.

6.4.6 Trustworthiness in Customer Relationships

Honesty

To entrepreneurs in all the three sectors (agriculture, services and manufacturing), honesty is the most important attribute that determines trustworthiness of customers in domestic, West African, and international markets. Honesty is important since it is impossible for agreements and contracts to cover all expectations in any contract or agreement (Arrow 1974), as a result, entrepreneurs expect that customers will do what they have promised to do. An honest customer abides by his or her promises and tries not to take advantage of entrepreneurs or defraud them. Honesty also relates to customers keeping promises to pay for goods or services supplied on trade credit. The expectation that exchange partners will perform their role in the agreement describes honesty and it is similar to goodwill trust (Tillmar 2006; Nooteboom 1996; Fukuyama 1995) and integrity (Mayer et al. 1995).

Trade Credit

Entrepreneurs, irrespective of the markets in which they trade, recognise trade credit as a very important trust expectation in entrepreneurial relationships. This is understandable given the limited access to bank finance (Abor and Quartey 2010; Amoako and Matlay 2015) and higher costs of financial debt due to higher interest rates and inflation in Ghana. Trade credit also enhances entrepreneurs’ strategies to boost accounts receivables and grow their businesses (Petersen and Rajan 1997). Yet, culturally specific norms of visits and payments guard trade credit relationships in Ghana. According to Amoako et al. (2018), in Ghana, the overwhelming majority of entrepreneurs develop trust in customers who make timely payments for goods already supplied. Often entrepreneurs ‘start a little at a time’ based on a number of transactions and a timely payments history based on a number of previous trade credit transactions and these often determine whether customers would benefit from a larger trade credit or not. Based on this approach, customers who have paid their previous trade credit as promised are seen to be trustworthy. Yet, the importance of timely payment varies from sector to sector. For example, in West African agriculture trade, entrepreneurs receive payment usually after the customer, who acts as an agent (efiewura), finishes selling the goods and takes commission, in a process that can last weeks. The difference in the sectors is due to differences in the norms governing the various sectors and markets.

Apart from timely payments, the vast majority of entrepreneurs assess the assets of partner entrepreneurs and organisations to ascertain their ability to fulfil payment obligations before trusting them. The ability to fulfil payment obligations relates closely to competence trust (Nooteboom 1996). In the assessment, entrepreneurs use the value of assets as a proxy for a partner’s capacity to offer or to pay trade credit. Entrepreneurs therefore usually visit their partner’s working place or home to collect information by assessing their assets such as equipment, machinery, and property. During these visits, entrepreneurs may talk to employees, family members, and at times members and leaders of the community to collect information on the reputation and therefore creditworthiness of their potential trade credit partners. Entrepreneurs rely on different types of information about the partner from the local community to evaluate the risks in trusting the partner company. It is also common practice for partners who request trade credit to be proactive and invite entrepreneurs to their business places and homes. The invitations to customers’ and suppliers’ homes and business places are very important because they enable entrepreneurs to locate their potential trade creditors in cases of default. In particular the invitations supposedly show the willingness of potential trade debtors to pay if they are offered trade credit, even though there are no guarantees that the trustee (debtor) will not relocate and ‘disappear’. Gathering information about the assets of trading partners is very important in Ghana, and in Africa in general, since there is limited public information on the credit history of individuals and firms (Owusu Kwaning et al. 2015). However, occasionally entrepreneurs may take a greater risk by trusting strangers and extending trade credit to partners they do not know, based on gut feeling.

Reputation

Another important attribute that enhances customer trust is reputation (Weiwei 2007). Ghanaian entrepreneurs like supplying goods and services to entrepreneurs and companies who have a good reputation. These are entrepreneurs or firms that are honest and well established, and have been in business for a while so have a track record. Companies that have economies of scale, better cash flow, and are unlikely to be bankrupt are appealing and, not surprisingly, entrepreneurs in Ghana often perceive larger organisations to be more trustworthy compared to SMEs. Consequently, in general entrepreneurs prefer to trust and supply goods and services to reputable larger companies or medium companies than to work with micro and smaller businesses, and the perception that reputable firms are old and large compared to young and small firms has been confirmed by academics (Schwartz 1974; Petersen and Rajan 1997). Yet, in trusting and working with larger organisations, and particularly state-owned organisations, entrepreneurs often become vulnerable due to power asymmetry and the tendency for delayed payments from state organisations.

Sharing Market Information

Communication among partners has a direct positive impact on supply chain partnerships (Chu 2006). Entrepreneurs in Ghana regard the sharing of information with customers to be another very important trust expectation. The majority of entrepreneurs explained that the sharing of information with customers enhances flexibility and quick responses to changes in domestic, West African, and international markets. In particular, it enables them to respond to fluctuations in market demands regarding pricing, timing, and export volumes, which helps to maximise profits and avoid losses (Amoako 2012). To share information, entrepreneurs use information and communication technologies (ICTs) including the internet, mobile phones, and emails. The sharing of information and good communication between exchange partners promotes what Sako (1998) and Lewicki and Bunker (1996) call goodwill trust and knowledge-based trust respectively.

6.4.7 Trustworthiness in Supplier Relationships

Within supplier relationships in domestic, West African, and international markets, honesty remains the most important trust expectation. Honesty is important as honest suppliers keep promises regarding product and service specifications in terms of quality, quantity, and delivery times. Honest suppliers do not take advantage of entrepreneurs or defraud them by manipulating contracts or misusing trade credit extended to them for the supply of goods/services for other purposes.

Quality Products/Service

To Ghanaian internationally trading entrepreneurs, another important supplier trust expectation is quality of products/services. The supply of quality products/services is important for both exporter-supplier and exporter-customer relations in all sectors, but more so for international markets. This is due to the international supplier-buyer value chains in which customers expect adherence to very high product specifications, breaches of which may entail penalties. Poor quality goods/services from suppliers put the reputation of smaller businesses at risk. To mitigate this challenge, some entrepreneurs develop trust-based relationships with suppliers by offering training and technical support to enable them to meet the high specifications required by international customers. This is particularly common in the agriculture sector where the competitive nature of global market demands, and strict regulations on food due to health and environmental concerns, have given rise to interdependence, cooperation, and mutual trust between entrepreneurs and their suppliers (Amoako 2012). Therefore, in the agriculture and food sector, entrepreneurs lean on farmers and suppliers in order to meet their obligations to their customers and this form of trust is similar to what Nooteboom (1996) and Sako (1998) term ‘competence trust’.

Punctuality

Another important expectation of supplier trust that is critical to the competitiveness of entrepreneurs in international markets is punctuality: that is, meeting delivery deadlines.

Punctuality is linked to the competitive nature of international trading as entrepreneurs are expected to meet supply deadlines and, based on this demand, they in turn expect their suppliers to meet delivery deadlines. Yet, while punctuality could be a major issue to entrepreneurs in all sectors, it is more important for those involved in trading in fresh produce, such as food, due to the short shelf life of their produce. The challenges of punctuality relate to cultural-specific norms of ‘African punctuality’, which refers to the flexible use of time in Ghanaian and African contexts (see Chap. 4). To reduce this challenge, internationally trading entrepreneurs develop trust-based collaborations with their suppliers in order to meet the stringent deadlines imposed on them by their international partners. This process involves the learning of new norms of punctuality (Amoako 2012; Amoako and Matlay 2015) and thereby, as actors, not yielding to existing norms and institutions. Punctuality as an expectation of reliability requires that exchange partners meet their obligations in export transactions and again Nooteboom (1996) and Sako (1998) describe this as ‘competence trust’.

Trade Credit from Suppliers

Entrepreneurs trading in domestic , West African, and international markets recognise that trade credit to or from suppliers is a critical expectation in entrepreneurial relationships (Amoako et al. 2018). Thus, entrepreneurs receive trade credit from suppliers who are trustworthy. Similarly, they extend trade credit to trusted suppliers. In competitive sectors, entrepreneurs who refuse to offer trade credit to suppliers when expected to do so may lose suppliers to competitors who are prepared to offer it. Yet, the potential for opportunism exists as suppliers can default and/or divert goods or services to another buyer. For example, in the food and agricultural sector, there is scope for opportunism, particularly when competitors offer farmers higher prices than those the entrepreneur had offered initially through trade credit. However, farmers who receive trade credit from entrepreneurs rarely divert their produce. Thus, trade credit enables entrepreneurs to work closely with partners to develop supplier trust. This dimension of trustworthiness relates closely to ‘leanability’ based on reciprocity and obligations to provide support to family members based on the traditional family system (Amoako 2012).

Sharing of Information by Suppliers

Sharing of information remains a key dimension of supplier trust in domestic, West African, and international markets. Within supplier relationships, the sharing of information with regard to changes in prices, volumes, deadlines, and quality enables entrepreneurs to quickly respond to changes in domestic, West African, and international markets. Timely information sharing on market prices and demand also allows entrepreneurs to maximise profits and avoid losses (Amoako 2012). Suppliers share information via face-to-face meetings and ICTs (notably mobile phones for calls, text messages, and emails).

Reputation

The reputation of supplier firms is an important attribute that also enhances supplier trust in Ghana. Entrepreneurs prefer buying supplies from well-established and known entrepreneurs and companies that have been in existence for a while, and as a result have a track record. Entrepreneurs often seek references from personal and business networks to identify such organisations (see Chap. 5). The reputation of a supplier serves as an assurance of product specifications regarding quality and reliable supplies. Firms with a good reputation may also offer competitive prices to entrepreneurs. However, cheap supplies may compromise quality and damage the reputation of the entrepreneur’s business and so the key issue in such transactions is related to value for money. However, reputable companies may require the payment of deposits which may adversely affect the cash flow of small businesses.

The customer and supplier trusts described above are, however, underpinned by personal trust developed between trading partners. Personal trust originates from previous exchanges and from the initial knowledge of the exchange partner and his or her demonstration of trustworthiness (Zucker 1986; Mayer et al. 1995; Chang et al. 2016). It may also originate from social networks and long-standing bilateral business relationships involving organisations (Welter and Smallbone 2006).

Ghanaian entrepreneurs, like their counterparts from other African countries, rely mostly on personal trust to enhance economic activity (Lyon 2003, 2005; Amoako and Lyon 2014). Entrepreneurs develop personal trust with other entrepreneurs and managers of key partner companies in order to develop or grow their businesses. Based on personal trust, entrepreneurs may receive trade credit, quality products, and timely delivery, all based on flexible arrangements using oral contracts that do not involve a lawyer. This is particularly important in weak institutional contexts such as Ghana where entrepreneurs have limited access to resources from formal institutions.

Case 6.2 demonstrates how entrepreneurs in weak institutional contexts may perceive trustworthiness based on the actions and behaviour of exchange partners. This case also shows how entrepreneurs draw on the logics of indigenous cultural institutions in trust development.

Case 6.2 Personal/Organisational Trust Development

Gifty is a dynamic and ambitious Ghanaian female entrepreneur who learnt her skills as an exporter after working with her sister in the clothing export industry. Later on she received training from the Ghana Export Promotion Authority and founded Top Creativity Industries in 2000, registering the firm in 2002. The company is located at Tema, the industrial hub of Ghana, where she manufactures and exports natural cocoa powder—Life Gold Natural Cocoa Powder—to Nigeria, Togo, and Benin in West Africa and to the United States. Gifty is a member of the Assorted Foodstuff Exporters Association and maintains good relationships with the Ghana Export Promotion Authority (GEPA), the state institution that supports SME exporters operating in the formal sector. GEPA organises training and trade fairs for small-scale exporters in the formal sector. Gifty also works closely with the Cocoa Processing Company, her main supplier. She has developed close working relationships with her customers in West African countries. She does not have a contract with any of her customers or suppliers but instead relies on trust by accepting and placing orders for products and raw materials via the telephone. She works closely with customers who are trustworthy; according to her these customers are ‘honest, truthful and God-fearing; when they say [in] two weeks I will pay the money they pay, they keep the promises and send the money’. Similarly, she has worked closely with her suppliers because ‘their quality is very good and the manager I deal with is very honest too’.

Gifty offers trade credit to her customers in West African markets to enable her to increase sales and grow her business. However, before offering trade credit to customers, she tests them based on timely payments for a number of previous transactions. Furthermore, before advancing trade credit to customers in West African markets, she visits their workplaces or homes to collect information on their reputation and assets including equipment, machinery, and property. During the visits, she may talk to employees, family members, and at times members and leaders of the community. She also offers gifts to the spouses and children of customers when she visits. Interestingly, often customers who request trade credit invite her to their homes and workplaces. According to her, the invitations enhance trust development because they enable her to trace potential trade debtors in cases of default. However, occasionally she takes a risk by offering small quantities of her products to customers who are relatively new and whose homes and workplaces she does not know and this happens when she perceives the customer to be God-fearing. Gifty therefore develops trust based on cognition, calculation, and at times habituation to build trade credit relationships. In 2017, she acquired a 4 acre-piece of land near Accra and registered a new company, Life Star Cocoa Processing Ltd., to take advantage of the high demand for processed cocoa from local and foreign customers. Currently, she is searching for trustworthy partners to invest in her new company. She is also looking for customers in China, Japan, and Dubai.

6.5 Trust Outcomes

The literature on entrepreneurship confirms that interorganisational trust directly or indirectly offers a variety of positive outcomes for interfirm relationships (see Welter and Smallbone 2006) and this is no different in Ghana. Personal trust with family/kinship contributes in cash and in kind to businesses in the start-up stage through inheritance, apprenticeships, or start-up capital (Clark 1994; Buame 2012). Furthermore, entrepreneurs access resources such as ideas, informal finance, larger networks, and market knowledge, from family/kinship. Family members may also become trusted business partners or apprentices and may also assist in conflict resolution (Amoako 2012; Lyon 2005). Similarly, there is a consensus among entrepreneurs that personal trust between entrepreneurs and their key partners enhances cooperation that in turn facilitate access to ideas, trade credit, larger networks, and market knowledge. Parallel institutional trust with trade associations also enhances legitimacy, advocacy, and access to markets, social security, and conflict resolution. Nonetheless, there is evidence that entrepreneurs experience trust violations and Chap. 7 will explore this in detail.

6.6 Conclusion

This chapter set out to examine the institutional logics that shape trust development, how entrepreneurs perceive trustworthiness, and the forms of trust developed in contexts of weak institutions. The discussions show that institutional logics of a range of societal institutional orders provide the basis of trust (see Fig. 6.1). The logics of weak legal systems and enterprise support institutions underpin the limited institutional trust in state and market institutions. In response, entrepreneurs mainly rely on logics of indigenous cultural institutions to develop personalised trust that enhances stronger obligations and reciprocity in working relationships. Entrepreneurs draw stronger elements of obligation in economic relationships from logics of language, oral contracts, trade associations, family/kinship and friendship, religion, punctuality, gift giving, and traditional justice systems embedded in chieftaincy. As a result, socio-cultural institutions underpin trust development (Saunders et al. 2010; Li 2016; Chang et al. 2016) and therefore trust can be habitual and routinised (Zucker 1986). The logics of some indigenous institutions that run side-by-side with state institutions provide the basis of trust that substitutes for limited institutional trust and the author refers to this form of trust as ‘parallel institutional trust’. In particular, trade associations provide parallel institutional trust that facilitates entrepreneurship by providing many critical services including advocacy, legitimacy, business information, training, welfare and opportunities for networking to members, and settling commercial disputes between members, and members and their trading partners. Not surprisingly, most entrepreneurs regard membership of these associations as crucial for survival as they enable entrepreneurs to take on some of the risk in a relationship. Some trade associations draw on a hybrid of traditional norms of chieftaincy and Western notions of organisation with leadership structures that include a queen or chief and a secretary.

Yet, relationships and interactions with officials of institutions, family/kinship and friendship, and customers and suppliers also shape entrepreneurs’ trusting behaviour. In these relationships, entrepreneurs base the trustworthiness of trustees primarily on the actions and behaviour of the trustee (Mayer et al. 1995; Zaheer et al. 1998). As a result, the actions and behaviour of officials of a state enterprise support institution, leaders of trade associations, or entrepreneurs owning and managing the partner SME influences trust development.

Thus, within working relationships with customers and suppliers, the entrepreneur’s trusting behaviour is shaped mainly by the trustworthiness and expectations of the partner (trustee) owning the micro or smaller business, or the manager or key boundary spanner of the larger organisation (Zaheer et al. 1998). As a result, the distinction between personal/organisational trust remains complex and unclear. This may differ in larger organisational contexts where the number of employees is higher and a number of managers may be involved in decision making. It may also differ in other economies where there is less power distance and in contexts where SMEs may have a larger number of employees.

This chapter shows that entrepreneurs draw on logics of cultural institutions to develop trust. However, it is also clear that as actors, entrepreneurs do not necessarily yield to institutions. For example, the development of new norms of punctuality and refusal to work with family members who are not trustworthy due to opportunistic behaviour (Amoako and Lyon 2014; Amoako and Matlay 2015), show how as actors, entrepreneurs in Ghana have the capacity to reflect and act in ways to counter the constraints and taken-for-granted assumptions prescribed by institutions (Abebrese and Smith 2014).

Trust enables entrepreneurs to access critical resources needed for start-up and enterprise development. These resources include start-up capital, apprenticeships (Clark 1994; Buame 2012), ideas, information, informal finance, larger networks, market knowledge, trusted business partners, and social security (Amoako 2012; Lyon 2005). Furthermore, trust enhances legitimacy, advocacy, access to markets, and conflict resolution in domestic and distant markets.

This chapter contributes to the literature in four ways. First, by presenting a framework that visualises a holistic approach to trust development in SME interorganisational relationships in an emerging economy and African context based on the entrepreneur (trustor), his or her trading partner (trustee), their relationship, and the external cultural norms that shape trust processes within relationships. Second, by reconceptualising the role of state and market institutions and identifying cultural-specific institutions that provide the logics that underpin trust development in entrepreneurial relationships in an African context. Third, by showing how personal/interorganisational trust comingles in SME contexts due to the dominant role of the entrepreneur who as an actor may develop trust in relationships in order to mitigate institutional weaknesses in Ghana. Fourth, by showing how as actors entrepreneurs do not necessarily yield to formal institutional constraints but respond by relying on alternative indigenous institutions.

Yet, notwithstanding these advantages, all the entrepreneurs shared experiences about violations of trust some of which greatly damaged relationships. The next chapter (Chap. 7) discusses trust violations in entrepreneurial relationships in the Ghanaian context.