5.1 Introduction

Africa has recently experienced a remarkable economic growth and real income per person has increased significantly, giving rise to opportunities for growth to entrepreneurs, investors, and businesses (Delloitte 2014). The continent is now regarded as an emerging market and a destination for businesses to invest, grow, and expand (BBC News 2018; George et al. 2016; Accenture 2010) and this has, in turn, given rise to a need to understand how to develop and manage entrepreneurial networks and relationships with businesses and customers in the continent. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and entrepreneurs are the main drivers of the economic boom, creating around 80% of the region’s employment (World Economic Forum 2015), and as a result, networking with African SMEs and entrepreneurs offers opportunities in and outside Africa (Biggs and Shah 2006).

Network theory asserts that networking enables entrepreneurs and firms to access resources more cheaply than they could be obtained from markets and to secure resources such as reputation that are not available in markets at all (Witt 2007). The development and management of diverse networks and relationships could enhance the growth of organisations (Kale and Singh 2007; Bruton et al. 2010). Particularly a new, small and entrepreneurial firm could obtain unique knowledge, competencies, and resources to alleviate in-house resource constraints (Birley 1985; Street and Cameron 2007; Aarstard et al. 2016).

Networks are particularly important for firms doing business in emerging economies such as Africa where state and market institutions are weak (Meyer et al. 2009). In these contexts, the personal networks and norms governing interpersonal relationships play a crucial role in firm strategy and performance (Peng et al. 2008). For example, Sakarya et al. (2007) explain that establishing networks with firms and other institutions could help mitigate the lack of information in emerging economies of Africa. Tesfom et al. (2004) also show that by relying on networks of intermediaries, suppliers, and customers based on long-term relationships, Eritrean entrepreneurs collaborate to penetrate international markets. The role of networks in Africa is important as state and market institutions are not strong and often resources for start-up and business growth are limited. In Senegal, entrepreneurs rely on personalised networks and relationships within groups to provide resources to support each other (Mambula 2008). Similarly, networks relationships with spouses and family members also provide resources for entrepreneurs in Ghana (Buame 1996; Amoako 2012). Yet, networks that the entrepreneur belongs to can also constrain entrepreneurship. For example, family members may demand more and contribute less to family businesses in terms of effort and commitment and this may lead to the collapse of businesses (Sorensen 2003).

Yet, the development of networks in Africa entails a further challenge relating to how culture influences networks (Klyver et al. 2008). Sets of meanings, norms, and expectations of society and industries, as well as trust, are all aspects of culture that underpin networks (Curran et al. 1995; Amoako and Matlay 2015).

As a result, where there is cultural difference or ‘psychic distance’ between two parties, developing cross-cultural relationships can be constrained due to different cultural norms and expectations (Zaheer and Kamal 2011; Dietz et al. 2010). For this reason, scholars involved in social network analysis have called for the examination of such processes globally (Klyver et al. 2008; Georgiou et al. 2011). However, many of the existing studies in this area have been done in mature markets and there is very limited knowledge about the patterns of entrepreneurial networks in Africa—and how they are shaped by the logics of cultural institutions (Tillmar 2006; Jenssen and Kristiansen 2004; Overa 2006; Amoako and Lyon 2014).

In this book, the author defines networks as the relationships that link actors with the external environment. Relationships are defined as the connections between actors and the external world and are broadly categorised as personal relationships (strong ties) and working relationships (weak ties) (Granovetter 1973). Personal relationships refer to pre-existing ties such as family and friends while working relationships refer to ties with business partners and acquaintances.

This chapter aims to draw on the institutional logic approach to investigate the ‘socially constructed assumptions, values, and beliefs’ by which entrepreneurs in Africa provide meaning to their networking activities (see Thornton et al. 2012). Specifically, this chapter focuses on the societal-level logics of state and indigenous cultural institutions that influence entrepreneurs’ decisions about trust development in entrepreneurial relationships in Africa (see Chap. 2 for a detailed discussion of the institutional logics approach). The key questions to be answered are: ‘What are the forms of entrepreneurial networks and relationships in Africa?’ and ‘How do logics of cultural institutions influence the development and management of entrepreneurial relationships in Africa?’

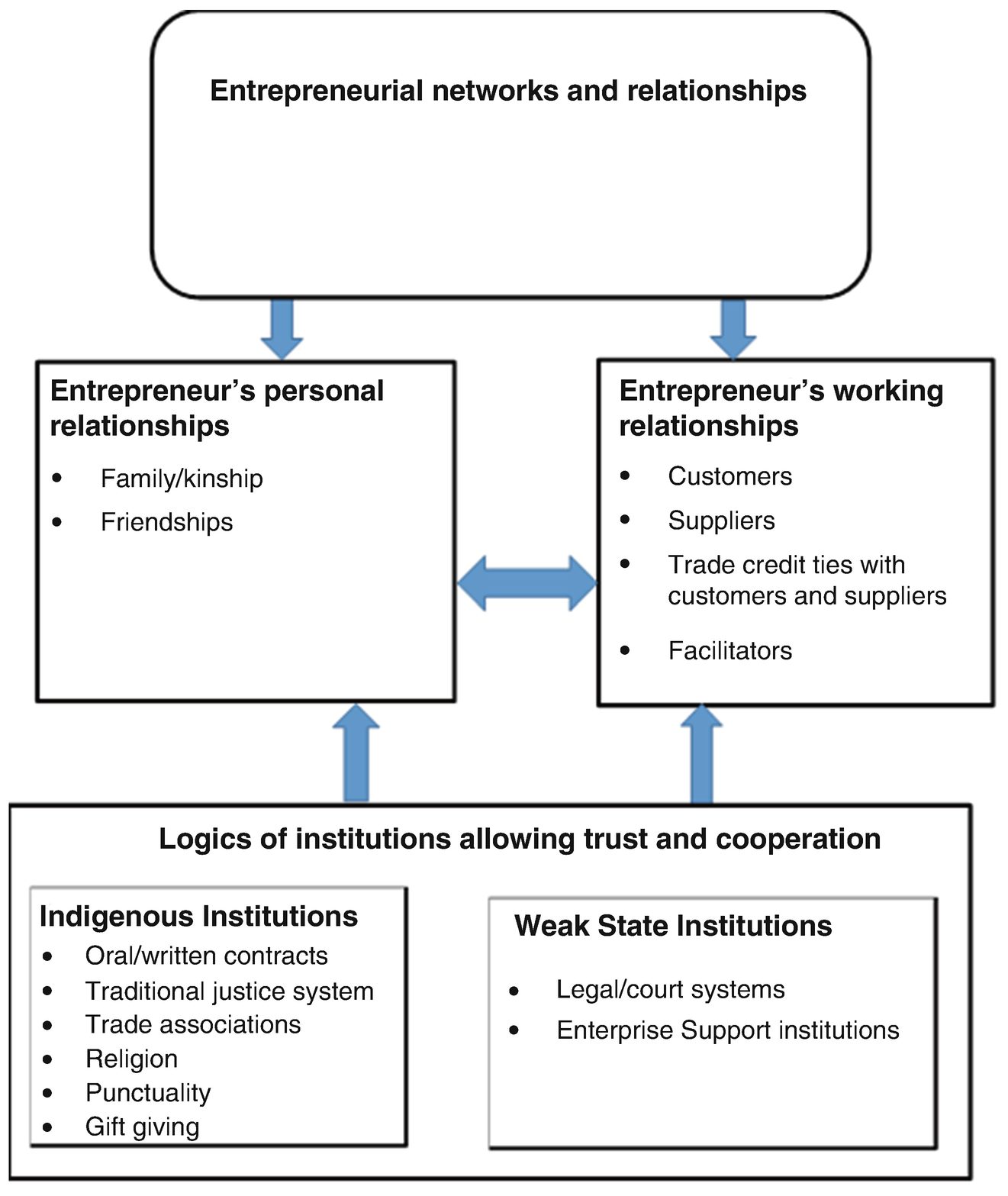

Entrepreneurial relationships and institutions in Africa. (Source: Author’s own research)

This chapter contributes to our knowledge in three main ways. First, it presents a framework to show the forms of entrepreneurial relationships and institutions that allow trust and cooperation to develop in weak institutional environments. Second, it offers an understanding of the processes through which entrepreneurs develop entrepreneurial relationships with customers, suppliers, and facilitators in the context of weak institutions. Third, it shows how the logics of African cultural-specific institutions shape the development of trust and cooperation and the management of entrepreneurial relationships. Understanding these logics is important due to their potential to give rise to differences in explanations and attributions for African entrepreneurial behaviour within relationships.

The rest of the chapter is organised in the following manner. The next section discusses the forms of networks and relationships that allow trust to develop. Then we discuss how culture-specific institutions shape the development of trust and management of entrepreneurial relationships in the context of weak institutions. The final section concludes the chapter.

5.2 Entrepreneurial Networks and Relationships in Africa

Recently, scholars regard entrepreneurship as a process that is embedded in networks, places, and communities that socially shape resources and opportunities (McKeever et al. 2014). The network approach is significant because it reasons that entrepreneurs as individuals neither exist nor operate in a vacuum, but instead other actors influence entrepreneurs in their social and business networks (Granovetter 1973; Aldrich and Zimmer 1986; Klyver et al. 2008). Networks extend the potential resource base of the entrepreneur (Aldrich and Zimmer 1986; Johannisson et al. 2002; Shaw 2006), and enhance the survival of the venture (Bruderl and Preisendorfer 1998). Thus, networks and relationships underpinned by trust are important to the entrepreneurial process (Casson and Della Giusta 2007; Burns 2016). This approach refutes the economic perspective that regards the firm is an atomistic actor governed by rational choice decision makers (Thorelli 1986; Johannisson 1995). It also rejects the psychological approach to entrepreneurship that focuses attention on the ‘heroic entrepreneur’ whose ingenuity enables them to mobilise resources to innovate and create value without recourse to social relations (see Chap. 2 for explanations of the economic rational approach and the psychological approach to entrepreneurship).

Even though networks are important for businesses operating in all markets, they are particularly essential for firms doing business in emerging economy contexts such as Africa where there are weak state and market institutions (Meyer et al. 2009).

The empirical study shows that entrepreneurs in Africa rely on different types of personal and working relationships. While personal relationships describe personal ties with family/kinship and friends, working relationships relate to ties with customers, suppliers, and enterprise facilitators (support institutions). However, often entrepreneurs develop close personal relationships with business partners based on family/kinship and friendship norms and these relationships may resemble family/kinship and friendships.

The personal and working relationships enable the identification of market opportunities, and offer access to critical resources such as market information, informal finance including trade credit, diverse skills, local knowledge, larger networks and markets, reputation, contract enforcement, and collective action. Thus, the relationships are fundamental to operating a successful business in Africa as, without them, it is nearly impossible to do business due to higher transaction costs that may be incurred.

The discussion in this chapter focuses on the personal and working relationships of entrepreneurs and the institutional logics that underpin trust development, and the management and governance of these relationships. The logics may be specific to a relationship, market, or industry. The next section analyses personal and working relationships developed and used by African entrepreneurs.

5.2.1 Personal Relationships

Entrepreneurs leverage ties in their personal as well as professional lives to access resources (Kregar and Antončič 2016). Personal relationships describe pre-existing ties with a strong degree of trust and emotional closeness with family/kinship and friends.

Family/Kinship/Friendship

In Africa, family/kinship, ethnic ties, and friendships are important in developing and managing entrepreneurial relationships. The empirical study shows that family values may promote honesty, diligence, and caring for one another, and entrepreneurs often rely on family members in the start-up process and to identify and build relationships with businesses. Family members also provide advice, market information, start-up capital, financial support, and help to identify business opportunities and potential business partners and employees.

On some occasions, family members and elders may mediate in resolving disputes between entrepreneurs and their business partners and in so doing assist in the enforcement of commercial agreements between partners. Some family members may also serve as employees, providing cheap labour, while others may become trusted business partners. Due to these benefits, many entrepreneurs regard working with family members as important. However, engaging family members in an African business divides opinions. To some entrepreneurs, family members remain the most trusted people who can be reliable and trustworthy employees or partners, and by employing them one can assist the family and improve the family’s economy. Others contest that family members may take advantage as employees or business partners due to cultural logics of communalism and obligations inherent in the family/kinship system. Some entrepreneurs cite instances when family members misappropriated money in businesses and refused to pay money back when offered loans. Previous studies show the enabling and constraining nature of the African family system on entrepreneurship. As stated in this chapter and in Chap. 4, while the African family may offer great support to entrepreneurs, excessive demands from family members may pose serious liquidity challenges and, in extreme cases, lead to the collapse of micro and smaller businesses (Kuada 2015).

In managing entrepreneurial relationships, most entrepreneurs draw on ties embedded in family/kinship to promote trust building and cooperation between them and their trading partners within the domestic markets and in markets across borders. For example, entrepreneurs exporting cola nuts (a local stimulant) from Ghana draw on trust built originally between Hausa emigrants in Ghana and their kinsfolk in northern Nigeria (Amoako and Lyon 2014).

Interestingly, norms of reciprocity and obligations inherent in the family/kinship system allow entrepreneurs to talk and work with business partners as ‘family members’ (Amoako and Matlay 2015). Generally, entrepreneurs refer to close working business partners (who are not necessarily family members) as mothers, sisters, fathers, brothers or family members.

Friendships are also important in starting, managing, and growing businesses in Africa. Friendships and professional ties with contacts during education in schools, colleges, and universities, and contacts developed at conferences, seminars, workshops, meetings, social events, and trade fairs, and in the exchange of business cards (see Aldrich et al. 1987) may provide resources including ideas, information, and start-up capital. As a result, the friendship ties of Africans are also important in enhancing access to resources for entrepreneurs and smaller businesses.

Nevertheless, in spite of the benefits of family/kinship and friendship ties in promoting business relationships, personal ties may also constrain the building of entrepreneurial relationships. For example, in some African cultures, particularly those dominated by Islamic cultural logics, it is culturally unacceptable for women to sit with men who are not their husbands. In these cultures, it is challenging for married female entrepreneurs to spend time, communicate with, and build sustainable relationships with male business partners. Furthermore, patriarchal African cultures stereotype women based on domestic roles that may confine them to household chores and that may constrain their involvement in developing businesses or business relationships. In such cultures, female entrepreneurs are often either divorced or single because society may regard them as outcasts (Amoako and Matlay 2015).

Additionally, family/kinship and friendship norms may also constrain competitiveness in entrepreneurial relationships due to cultural-specific norms that render it morally wrong to abandon a ‘brother’ or ‘sister’ even though the business relationship may not be very beneficial. African family/kinship norms may also encourage family members to ignore rules in organisations or terms in contracts and may constrain trust building and enterprise development. Family/kinship and friendship may sometimes also pose immense challenges to some African entrepreneurs and SMEs. Amoako and Lyon (2014) refer to these paradoxical norms as ‘the paradox of the family’, see Chaps. 4 and 6 for details. However, the personal trust in family/kinship and friendships is critical for entrepreneurship due to lack of institutional trust.

5.2.2 Entrepreneurial Working Relationships

The entrepreneurial relationship management process starts with the entrepreneur (as an actor) building relationships with potential customers and suppliers and other key stakeholders (Shane 2003; Welter and Smallbone 2011), and these relationships are critically important for all firms irrespective of size (Morrissey and Pittaway 2004). In this sub-section, the author examines entrepreneurial relationship development processes in Africa.

Customer Relationships

Entrepreneurs in Africa develop relationships with key customers in both domestic and international markets. Developing and managing key customer relationships is critical for the success of businesses (Hollensen 2015; Berry 1995; McKenna 1991). Customer relationship management (CRM) approaches focus on attracting, maintaining, and enhancing customer relationships (Berry 1995; McKenna 1991). The process includes attracting, developing, and building sustainable relationships with the most important customers to enhance superior, mutual, value creation. The long-term business-to-business (B2B) relationships involve repeated exchanges, cooperation, and collaboration that helps to reduce transaction costs for the partners involved (Berry 1995; Hollensen 2015; Parvatiyar and Sheth 2001).

The empirical study shows that African entrepreneurs attract and develop new customer (B2B) relationships through three main approaches. These approaches are networking and referrals, market research, and promotions. Yet, these three approaches are not mutually exclusive and entrepreneurs may deploy a number of them at the same time.

In the first approach, entrepreneurs rely on networking and referrals through personal and working relationships. African entrepreneurs ask for referrals from family members and friends as well as colleagues in trade associations, customers, and suppliers. Trade associations and state enterprise support organisations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and donor organisations may provide market information, organise training, and hold trade fairs that may open up new market opportunities in both domestic and international markets. Some entrepreneurs also attend seminars and workshops organised by these enterprise support institutions during which they talk about their businesses, products, and services and attempt to use the opportunity to identify and link up with potential customers. Satisfied customers and suppliers also serve as referrals for other businesses and entrepreneurs.

In the second approach, entrepreneurs prospect for business by researching and contacting potential customers. A significant number use information communication technologies (ICTs), mainly mobile phones, to call and send text messages to potential partners. Others search the internet and social media particularly Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and LinkedIn to identify suitable business partners who may need or like their products and services. While all entrepreneurs may use networking and referrals, the use of the internet and social media is particularly popular among the well-educated and mostly younger generation of entrepreneurs. Apart from mobile phones, the internet, and social media, some entrepreneurs send emails to potential customers. Thus social media and ICTs in general enable entrepreneurs owning and managing SMEs to provide basic information about products and services to customers (Parida et al. 2009). Conversely, social media and ICTs also allow customers to manage relationships with entrepreneurs and this can be detrimental. For example, negative customer reviews can adversely affect the brand image and reputation of a business (see Gensler et al. 2013). Apart from social media and ICTs, a significant number of entrepreneurs use the traditional market research methods by visiting potential customers in their workplaces and in open markets to show samples/pictures of products/services and to solicit for business.

Entrepreneurial customer attraction strategies. (Source: Author’s own research)

In international trade, entrepreneurs often rely on networking with partners in foreign markets to distribute their products. For example, small-scale food exporters in West Africa rely mainly on customers who are agents embedded in the landlord (efiewura) system (see Chap. 4) to successfully trade across the West African region (Lyon and Porter 2009; Amoako and Lyon 2014). However, a minority of small-scale entrepreneurs may rely on family/kinship ties that may cut across national borders.

Supplier Relationships

Supplier relationships are very important to entrepreneurs and all firms including those in Africa. In order for entrepreneurs and firms to acquire materials and services from suppliers (Scully and Fawcett 1994), they often spend over 50% of turnover on supplies. Hence, managing supplier relationships is critically important for the competitiveness of all firms. However, it is more important to entrepreneurs owning and managing SMEs due to the lack of resources (Morrissey and Pittaway 2004; Sako and Helper 1998).

African entrepreneurs develop new supplier relationships through networking and referrals from family/kinship, friends, NGOs, donors, trade associations, customers, and suppliers. Entrepreneurs often pitch their businesses, products, and services to prospective suppliers through conversations and telephone calls. They may also search on the internet, websites, and social media such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and LinkedIn to identify and contact suitable suppliers. Entrepreneurs often visit workplaces of potential partners to develop supplier relationships. Conversely, most suppliers contact entrepreneurs to promote their products and services.

Building long-term relationships with suppliers is important as it allows access to reliable and regular supplies and at times trade credit. Entrepreneurs involved in agriculture, manufacturing, and services rely on suppliers for raw materials and other inputs they use. Agricultural produce supplied to entrepreneurs includes pineapples, mangoes, vegetables, oranges, cashew nuts, cola nuts, maize, spices, poultry, egg, meat, and other fruits. Some of the raw materials supplied to entrepreneurs in the manufacturing sector include raw gold, shea nuts, spices, fruit, glass, timber, and chemicals. Supplies to entrepreneurs in the services sector—such as engineering, consultancy, and financial services—include spare parts, stationery, computers, printers, telephones, fax machines, and other ICTs. Trust and trade credit underpins long-term customer and supplier relationships.

Trade Credit Relationships with Customers and Suppliers

While bank financing could be the primary source of credit in advanced economies followed by trade credit (Wilson 2014), trade credit remains the most important source of financing for African entrepreneurs due to weak institutions and lack of access to formal forms of finance (Bruton et al. 2010; Mitra and Sagagi 2013).

Trade credit underpins most economic exchanges in domestic and cross-border exchanges in Africa, hence in some sectors it is important to provide and accept trade credit in order to run a successful business in Africa. This is because generally, there is a lack of bank finance and, when available, the higher cost of bank loans make them less useful so entrepreneurs strategically respond to this constraint by growing their businesses through the offer and acceptance of trade credit to trustworthy customers and from suppliers. Trade credit ranges from cash advances for goods, cash loans, and capital investment in projects (Amoako 2012). The logics of trade credit allow entrepreneurs to provide goods and services to trusted customers and receive supplies from suppliers if they are deemed trustworthy. Within trade credit relationships, entrepreneurs may receive cash transfers even before they supply the goods. This happens when demand for particular products increases in markets. Similarly, entrepreneurs extend trade credit to customers and suppliers in domestic and foreign markets. For that reason, entrepreneurs who refuse to offer trade credit may lose customers or suppliers to competitors who are prepared to offer it. Trade credit enables entrepreneurs selling to increase cash flow while those buying can secure reliable supplies and, in so doing, may enhance SME profitability (Martínez-Sola et al. 2014) and growth.

Yet, sometimes entrepreneurs encounter dishonest trading partners who default and renege on trade credit agreements in both domestic and international markets. In these circumstances, entrepreneurs rarely resort to the courts given the costs and challenges with the legal/court systems. Instead they draw on logics of indigenous cultural institutions, notably trade associations, family/kinship, and religious and community leaders/chiefs to enforce trade credit contracts. Chapters 6, 7, and 8 will discuss this in more detail. Case 5.1 shows how a young African social entrepreneur develops and manages her relationships with suppliers.

Case 5.1 Developing and Managing Entrepreneurial Relationships in Africa

Sally is from the Gambia and she completed her PhD in September 2018 in the UK. She owns 18 Forever, a social enterprise that aims to create employment opportunities for artisans in Africa. She explains that in most African countries there are many artisans with skills but who are unemployed and her company aims to enhance their employment opportunities. Currently, the company employs six people and manufactures in the Gambia, Nigeria, and Kenya. Manufacturing in each market focuses on particular products using African prints: dresses and jackets in the Gambia, handbags and clothing bags in Nigeria, and skirts and kimonos in Kenya. The products are sold online mainly to customers in the UK.

To develop entrepreneurial relationships, she needed to identify partners and Sally used referrals and undertook market research by walking through deprived neighbourhoods to identify artisans who she could work with. In the Gambia, she visited the local markets and neighbourhoods and talked to artisans before choosing her current partner. In the particular case of Kenya, she discussed her search for partners with a friend who she met during a conference in Portsmouth, UK in 2015. The friend knew a lady artisan in Kenya who was highly skilled but not making much money to support herself and her two children and he recommended her to Sally. When her friend returned to Kenya, he introduced the artisan to Sally who then spoke to her and asked for images of her products. After receiving the images, she was impressed and proceeded to place her first order for six products. She received the products through her friend and with the exception of one product, she was satisfied. She provided feedback on her concerns about the one product that was defective and then offered the artisan an application form to complete and a contract. Similarly, Sally identified an artisan in Nigeria based on a referral from her sister who personally knew the artisan.

To develop and manage the relationships, Sally collected a lot of information about the artisan partners which has enabled her to know details of where they live and work and they have been incredibly good partners. As a result of the cordial relationships, the artisans refer to Sally as a sister, as practised in Kenya and Nigeria. To sustain the relationships, Sally also gives gifts to her partners particularly at Christmas and when she pays for supplies she often adds a little for them to buy small gifts for their children. Sally explained that ‘It is how I was raised and in the Gambia that is a cultural way of doing business and when you buy in the market you will be given something more and that is our culture’. Sally has developed WhatsApp groups for her partners in Kenya, the Gambia, and Nigeria and communicates regularly with them.

Facilitator Relationships

In addition to customers and suppliers , there are a number of state bodies charged with enterprise support in the various African countries. State-backed organisations provide services including information on markets, products, management training, financing, networking, and organising of trade fairs to a limited number of entrepreneurs and smaller businesses that operate in the formal sector and have registered with them. The limited scope of the services provided may originate from the limited resources allocated by governments.

Apart from state institutions, African entrepreneurs develop relationships with other organisations ranging from NGOs, donors, and other international bodies to private sector organisations. However, the scope of the services provided by these institutions also raises concerns due to lack of support to the many small firms in the informal sector that contributes about 55% of Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 80% of the labour force (Buruku 2015).

In addition, there are a number of agencies from countries such as the United States, Germany, the UK, Denmark, Japan, Sweden, France, the Netherlands, Canada, and China that support enterprise development activities in a number of countries in Africa. The services include managerial training, networking, and small grants, and information on international market opportunities, international standards, and environmental issues. Nevertheless, critics argue that most of the services provided serve the interest of Western or donor institutions as the services primarily target the formal sector (Hearn 2007).

Recently, there has been increased interest in investment banks and private sector organisations supporting entrepreneurship in Africa. For example, the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the African Development Bank (AfDB) in partnership with the European Commission launched the Boost Africa Initiative in 2016 to provide investment funds, technical assistance, and an innovation and information lab to foster an entrepreneurial ecosystem on the continent. The project is unique due to its emphasis on supporting ventures that are usually too small, too risky and too time consuming. The project also includes a sizeable technical assistance package (EIB 2016).

Apart from international agencies, there are a number of private initiatives such as Afrilabs that provides a network of innovation centres across a number of African cities with the aim of raising successful entrepreneurs who will create jobs. Others include Funds 4 Africa which is a funding research site that provides opportunities for entrepreneurs to attract and link up with investors in different entrepreneurial projects.

In spite of these support initiatives, there is a wide gap in the institutional support environment in many countries and many industry- and trade-based associations have sprung up to fill the gap by providing the support services needed for entrepreneurs. Further on in this chapter and subsequent chapters, there will be discussions on the unique role of trade associations in facilitating entrepreneurial relationships.

5.3 Indigenous Institutions Shaping the Development and Management of Entrepreneurial Relationships in Africa

In order to understand the process of managing entrepreneurial relationships in Africa, it is important to emphasise that entrepreneurs and their firms are embedded actors in institutional environments (see Granovetter 1973 and Chaps. 2 and 4). Furthermore, the institutional logics approach focuses attention on how cultural dimensions both enable and constrain social action (Thornton and Ocasio 2008). The discussions in this section therefore highlights how entrepreneurs as actors use cultural logics to interpret and make sense of the world while the logics offer resources for relationship building and decision making (Vickers et al. 2017). Figure 5.1 focuses attention on the weak legal and enterprise support institutions, family/kinship and friendships, oral contracts, traditional justice systems, trade associations, religion, punctuality, and gift giving. It is equally important to highlight that these norms are not exhaustive as Africa is vast with a rich and diverse culture. Hence other cultural logics may pertain to particular countries, industries, sectors, and markets and there is a need for understanding those that are critical for doing business in each context. The discussions in this section focus on the key common norms that cut across cultures and are critically important in developing and managing entrepreneurial relationships. These norms are not mutually exclusive as entrepreneurs may deploy a number of them simultaneously depending on the nature of specific relationships, associations, and/or the industry, sector, and market.

5.3.1 Weak Legal and Enterprise Support Systems

In managing relationships, entrepreneurs draw on the logics of weak legal systems and state support institutions in African economies. Legal systems influence relationship development and management due to the impact on contract enforcement (North 1990). However, as stated in Chap. 4, generally, entrepreneurs from most African countries rarely engage with the legal system due to perceptions of it being weak, corrupt and unable to support contract enforcement for smaller businesses (Bruton et al. 2010; Amoako and Lyon 2014). Furthermore, there is limited enterprise support from the state and most entrepreneurs rely on trust in indigenous institutions to develop personalised relationships that enable them to access needed resources (Sakarya et al. 2007).

5.3.2 Oral Contracts

African entrepreneurs rarely use written, legally binding contracts that is the norm in developed countries. Traditionally, oral contracts via face-to-face verbal conversations, telephone calls, and messages through mobile phones and social media underpin entrepreneurial relationships with customers and suppliers in domestic and regional African markets. Hence, entrepreneurs usually distribute goods and provide services to customers and/or receive goods and services from suppliers based on oral contracts. However, it is important to note that, in most cases, entrepreneurs make records of the goods/services supplied or received on invoices, notebooks, and sheets of paper.

In contexts where there may be a lack of prior knowledge in domestic or regional markets, face-to-face oral contracts are agreed in the presence of trade association members, or two or three other people, who serve as witnesses (Amoako and Matlay 2015).

The use of oral contracts is widespread for a number of reasons. First, such contracts are simple and efficient, as they do not involve time searching for lawyers who may often charge huge amounts of money. Second, some of the entrepreneurs engaged in micro and small businesses are illiterates who are unable to read, write, or understand written contracts. Third, trust is the basis of economic exchange among smaller businesses, hence some partners even become suspicious if entrepreneurs insist on written contracts.

Oral contacts are based on trust and there are expectations that customers and suppliers will honour their obligations by, for example, supplying the agreed quantity and quality of goods. While oral agreements may not be enforceable within the legal systems of African countries, in the overwhelming majority of cases, the exchange partners honour their obligations. This corroborate the importance of social norms, trust, and informal collaborations in contexts such as Africa where formal institutions that enforce contracts are less developed (Welter and Smallbone 2006; Bruton et al. 2010), and traditionally informality remains the norm for economic exchanges.

In spite of the widespread use of oral contracts, some entrepreneurs engaged in international trade with partners outside of Africa rely on a memorandum of understanding (MOU) while a few others utilise written contracts in relationships. Furthermore, entrepreneurs who develop relationships with enterprise facilitators such as donors and private institutions often have to sign contracts in order to benefit from the services offered by these institutions.

Interestingly, in most cases the entrepreneurs who benefit from these services have worked, lived, or travelled in Western countries or are well educated or have an understanding of Western business culture.

The effectiveness of the norms of oral contracts is embedded in the traditional African justice system that enhances conflict resolution across African societies.

5.3.3 Traditional Justice System

Entrepreneurs rely mostly on the traditional justice system which runs parallel to the formal justice systems in repairing trust and resolving conflict (Tillmar and Lindkvist 2007; Amoako and Lyon 2014). The legal/court systems of African states were imposed by colonial authorities and have, in the main, been culturally incongruent (Myers 1992) and less useful for entrepreneurship development. In contrast, traditional courts draw on the communal nature of African societies to seek the truth, restore social harmony, punish perpetrators, and compensate victims. This is contrary to Western conflict resolution imposed by the existing formal legal and court systems that draw on individualism, and are mainly retributive, adversarial, and based on a winner-loser approach (Myers 1992; Ingelaere 2008). In the context of SMEs, comparatively, the traditional conflict resolution system remains relatively efficient and more enterprise friendly than the court system because it is informal and simple, cost effective, involves quicker processes that saves time, and is less corrupt.

It is not surprising that the traditional African justice system is embedded in a number of cultural institutions that facilitate entrepreneurship including those of family/kinship, trade associations, and religion and these are important in resolving conflicts and disputes between entrepreneurs and their trading partners.

5.3.4 Trade Associations

Trade associations are very important in managing entrepreneurial relationships in Africa and the overwhelming majority of African entrepreneurs are members of associations. Trade associations often make the rules, mediate in disputes, and enforce contracts between entrepreneurs and their exchange partners. While the conflict resolution approaches and structures used by trade associations are often shaped by the traditional African justice systems, the structures of many trade associations are a hybrid of Western and religious norms and values. For example, in Nigeria, small entrepreneurs in the open markets across the country prefer to report defaulters to the association rather than to the courts. The trade associations use the traditional court processes to resolve the conflicts. The processes are flexible, fair, less time consuming and usually free. Hence, they function as parallel institutions to the courts and fill the void left by the weak and inaccessible legal institutions. In this way, trade associations provide ‘parallel institutional’ trust. Trade associations are therefore critical for the survival of smaller businesses (see Chap. 4 for more information on the nature of the associations and Chap. 6 on how trade associations enhance trust development in entrepreneurial relationships in Africa).

5.3.5 Religion

Religious norms shape the nature of entrepreneurial networks and trust-building processes (Drakopoulou Dodd and Gotsis 2007; Dietz et al. 2010; Dana 2010). Among African entrepreneurs, it is evident that shared religious beliefs foster relationship building. This confirms previous studies showing how coreligionists build strong personal ties, friendships, and trust with fellow worshippers (Drakopoulou Dodd and Gotsis 2007; Dana 2010), and depend on fellow believers for credit and information (Dana 2006; Dana and Dana 2008; Galbraith 2007). However, the majority of entrepreneurs build business relationships with exchange partners irrespective of religious background.

Additionally, entrepreneurs sometimes rely on religious leaders and logics of religion to resolve disputes with business partners. Some entrepreneurs rely on ministers of religion—pastors, imams, and clerics—and traditional religious leaders instead of the courts in resolving disputes and to enforce agreements between entrepreneurs and their partners. Nonetheless, there are fake religious leaders who may deceive entrepreneurs if they are followers based on claims of having links to the spirits and receiving ‘divine’ messages in order to defraud them (De Witte 2013).

In desperate circumstances, some entrepreneurs may draw on religious beliefs to invoke curses from God, Allah, and/or the smaller traditional deities and gods to sanction partners who refuse to abide by contractual obligations (Amoako and Matlay 2015). Yet, it is not clear whether the threat of these types of sanctions is effective in relationships with partners who do not share common religious values and norms. Additionally, norms of superstition and fatalism originating from Christianity, Islam, and Animists belief systems may also inform the decision of entrepreneurs to accept vulnerability and rebuild trust after apparent violations by business partners, and this will be explored in more detail in Chap. 7. Another indigenous institution used to develop and manage entrepreneurial relationships with key partners is gift giving.

5.3.6 Gift Giving

Gift giving is an important part of African culture that fosters peaceful coexistence and harmony and is legitimate (Yanga and Amoako 2013; Ayittey 1991; Kenyatta 1965). Entrepreneurs offer gifts to and/or receive gifts from business partners. The gifts include small amounts of cash, food items, toiletries, clothing, jewellery and so on. Even though entrepreneurs may offer gifts to business partners or receive gifts from partners throughout the year, gifts are particularly given or received during celebrations, mostly on religious holidays such as Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha, Christmas, and New Year. The gifts serve as acts of appreciation and may help to gain favours; they may also help build and cement relationships through indebtedness, reciprocity, and control. Even though there is a consensus among entrepreneurs on gift giving in entrepreneurial relationships, there is lack of agreement on whether gift giving to public officials enhances bribery and corruption in Africa. The contrasting views of entrepreneurs, however, reflect a bigger debate on the ethics of gift giving and its role in the perpetuation of corruption among state officials in Africa (see Chaps. 4 and 6).

Case 5.2 Gift Giving and Entrepreneurial Relationship Management in Africa

Mary (anonymised) is the owner/manager of a small-scale food exporting business based in Douala in Cameroon. She exports most of her foodstuffs to neighbouring Equatorial Guinea and Nigeria. She explained that trust underpins her business with key customers and suppliers and she offers trade credit to those she trusts. She emphasises that ‘I know their place, I know where they live, I know everything about them, I don’t give trade credit to people I don’t know’. Knowing her trade credit partners enables her to trace them in case of default. In terms of managing key relationships, she communicates regularly on her mobile phone with her partners and also occasionally offers gifts to and receives gifts from them. She offers gifts in appreciation to customers who have been faithful and to those who have worked with her for a long time. She explains that ‘appreciating people is part of our culture, it is cultural, so there is nothing wrong with it’. Mary may offer gifts to her trading partners at any time of the year, nonetheless she give the gifts particularly during festive occasions like Christmas or during the Islamic festivals of Id el Maulud or Id el Fitri and the gifts range from food items, chicken, small amounts of cash to toiletries. She disclosed that her Christian faith provides her with values and her relationship development is based on shared values and beliefs in her business, and yet, she does business with partners irrespective of their religious beliefs. Mary is a member of the local food exporters association.

5.4 Conclusion

This chapter sets out to examine the forms of relationships African entrepreneurs develop and how they manage these relationships in the context of weak formal institutions. This chapter shows that a significant number of entrepreneurs utilise personal relationships with family/kinship and friendship in order to access resources such as information, capital, customers, and markets. African entrepreneurs also develop and use personal relationships with customers and suppliers who may not necessarily be family members, kinsfolk or friends by drawing on norms of reciprocity and mutual obligations of family/kinship and friendship in their relationships. As a result, personalised trust helps to reduce opportunism and enhance economic exchanges (Granovetter 1973; Berry 1997; Johannisson et al. 2002). Relationships with state and non-state enterprise facilitators and intermediaries also remain important despite the limited number of entrepreneurs supported. Apart from trade associations that cater for entrepreneurs in both informal and formal sectors, the services and support from facilitators are often limited to entrepreneurs operating in the formal sector while those in the informal sector that contribute about 55% of the GDP of African countries are ignored (Buruku 2015).

To develop and manage relationships with customers and suppliers in domestic and African markets, entrepreneurs draw on logics of indigenous cultural institutions and norms. These are logics of oral contracts, traditional justice systems, trade credit, family/kinship and friendship, religion, trade associations and gift giving. These logics enable entrepreneurs to develop personalised relationships with customers, suppliers, and some facilitators in domestic markets and in markets across the continent. While these indigenous institutions are embedded in African societies, some of the institutions such as trade associations may be a hybrid of Western norms. However, in relationships with partners outside of Africa, entrepreneurs have to rely on logics of Western business institutions including memorandum of understanding and written contracts. This chapter confirms that in the context of weak institutions, entrepreneurs draw on socio-cultural institutions and norms to build relationships (Lyon 2005; Welter and Smallbone 2006; Tillmar and Lindkvist 2007). Furthermore, it highlights how entrepreneurs operate in the context of weak formal institutions by relying on indigenous institutions that substitute for state and market institutions (Estrin and Pervezer 2011) and yet very little is known about these indigenous institutions.

This chapter contributes to the literature in three ways. First, it presents frameworks to show the forms of entrepreneurial relationships and institutions that allow trust to develop in entrepreneurial relationships in weak institutional environments. Second, it describes the processes through which entrepreneurs develop entrepreneurial relationships with customers, suppliers, and facilitators in the context of weak institutions. Third, it presents the debates, contradictions, and misunderstandings surrounding some of the socio-cultural institutions and norms that provide the logics that facilitate entrepreneurial trust development and the management of entrepreneurial relationships in Africa. As a result, it contributes to an understanding of the complex processes of developing and managing sustainable entrepreneurial relationships with customers, suppliers, and enterprise facilitators in Africa.

The next part, comprising Chaps. 6, 7 and 8, will examine the development of trust, trust violations, and trust repair in an African context.