CHAPTER 6

Case Study 2: North American Rock Art

For a second case study of shamanistic rock art, I turn to North America – which is just about as far from southern Africa as it is possible to go. There is no possibility of interaction between the two regions, or diffusion of religious beliefs from one to another: North American shamanism is related to the circumpolar and Siberian expressions; southern African San shamanism is a distinct expression.

North America is a vast continent, and there are many Native American traditions and language groups. In this short chapter, I adopt a limited, generalized approach to this diversity and, whilst acknowledging significant differences between regions and cultural groups, concentrate by and large on commonalities between communities living in the far west and Great Basin. In taking this generalized approach, I am following a long history of American anthropological research; for a century, the cultural unity of the far west has been recognized. The region comprises three closely related ‘culture areas’, as defined by Alfred Kroeber, the early North American anthropologist who worked at the University of California.1 The differences between these three areas are mostly adaptive and related to subsistence, rather than to belief. It is also in these regions that the most recent and illuminating rock art research is being done. It could be argued that this geographical focus is, in some ways, an unsatisfactory compromise, but limited space necessarily entails summary. Still, by adopting this approach, I am able to concentrate on aspects of North American rock art that are germane to the principal themes of this book.

In Chapter 5, I made a number of key points concerning

– the neurological origin of the tiered shamanistic cosmos,

– rationalizations (flying and underwater and subterranean travel) of the universal sensations of altered states of consciousness,

– the manifestation of visions on rock surfaces,

– the integration of belief, vision and cosmos, and

– the social impact of ‘fixed’ visions.

I need not repeat those fundamentals here. Instead, I proceed directly to the ways in which the points I made in the southern African case study resurface in an examination of North American rock art.

Historical setting

A comparison of the ways in which rock art research has been conducted in southern Africa and North America reveals parallels and differences deriving from the methodological approaches that researchers adopted on the two continents. Unlike in southern Africa, those in North America never really doubted that much (to be sure, not all) of the continent’s hunter-gatherer rock art was in some way associated with shamanism.2 So many Native American foraging communities practised, or had practised, forms of shamanism that the implication seemed inescapable. But that was not the whole story.

Although there was, in North America, no west European influence in the person of the Abbé Henri Breuil, as there was in southern Africa, there was a long-established tradition of hunting-magic explanations, perhaps as part of a form of shamanism but more commonly in isolation from broader conceptions of religion, myth and society.3 We need not consider the various forms of the hunting-magic explanation: recent researchers have shown them to be inadequate and lacking in ethnographic support.4

Nor need we dwell on the widespread belief that North American rock art was concerned with astronomical beliefs and that the sites themselves monitored the passing of the seasons. It is true that astronomical beliefs permeated Native American cosmology and that some celestial phenomena were apparently depicted in rock art. But the idea that sites were used for solstice observations is ethnographically unsupported. As the American archaeologist David Whitley5 points out, studies of putative alignments are based on ‘counting the hits and ignoring the misses’. The occasional sites that seem to support the argument are probably random.

Rather than pursue these and other explanations that have no ethnographic foundation, it will be more profitable to move on to writers who recognize the importance of Native American beliefs, rituals and ways of life. As Whitley wisely remarks, ‘we will always be on firmer interpretive ground when we use indigenous voices, directly or indirectly, to guide us in our understanding of this traditional art’.6 To be sure, Lévi-Strauss hit the nail on the head when he wrote: ‘Against the theoretician, the observer should always have the last word, and against the observer, the native.’ 7

North American ethnography

At the beginning of the 1970s, Thomas Blackburn began to explore an early twentieth-century North American ethnographic collection, though not with the specific aim of explaining rock art. From the outset, he set his face against the ‘obfuscating verbiage of structuralist approaches to oral narratives’.8 Instead of seeking sets of binary oppositions, as Lévi-Strauss did in his monumental and somewhat intimidating study of North and South American myths, Blackburn was interested in elucidating ‘the fundamental issue of the interrelationships between oral narratives and other aspects of culture’.9 This is, of course, the methodological approach that southern African researchers adopted when, in the late 1960s, they sought connections between the Bleek and Lloyd nineteenth-century ethnography and rock art images.

For Blackburn, John Peabody Harrington took the place of Bleek and Lloyd. Harrington was an ethnologist and linguist who was born in 1884; he died in 1961. During his colourful life he amassed vast quantities of material from virtually every North American linguistic group. The Smithsonian Institution, which was his employer for many years, collected his records after his death. Most of the material remains unpublished. Blackburn was not able to comb through all the over 400 large boxes in the Smithsonian; instead he concentrated on Harrington’s work with the Chumash, who lived on the west coast of North America in the vicinity of present-day Santa Barbara. Harrington had begun work with the Chumash in 1912. Like Bleek and Lloyd, he became conversant with the indigenous language.

Blackburn noticed that ‘magic and the supernatural play a prominent role in most of the [Chumash] narratives’.10 This is exactly what we find in the Bleek and Lloyd Collection. Indeed, any dichotomy between the natural and the supernatural is likely to be a Western imposition on traditional huntergatherer communities. Another, related, parallel is also important. Blackburn found that the ‘Chumash universe…consists of a series of worlds placed one above the other. Usually three such worlds are described’.11 This is, of course, the tiered shamanistic cosmos that I described in Chapter 4 and, in Chapter 5, identified amongst the San. Again like the San, the Chumash recognized shamans of various types; they performed the kinds of tasks that I listed in Chapter 4. As a result of his reading of Harrington’s notes, Blackburn concluded that Chumash rock art was the work of shamans.12 From there, it was but a short step to take up Geraldo Reichel-Dolmatoff’s work with the Colombian Tukano (Chapter 4) and to find parallels between Chumash geometric rock art images and the entoptic phenomena of the first stage of altered consciousness.13 Other North American writers followed suit; they included Klaus Wellmann, 14 Werner Wilbert15 and, especially, Ken Hedges of the San Diego Museum of Man.16 This work was not restricted to the Chumash: evidence for the depiction of shamanistic visions was found across the American Plains and the West.

The neuropsychological work that Blackburn triggered undoubtedly set the stage for major advances in North American rock art research, but a methodological problem remained; the study of North American rock art did not, at first, blossom as one might have expected it to. As Blackburn rightly pointed out, the principal challenge is to demonstrate links between the ethnography and other components of culture – including rock art. What was needed was a sustained, detailed, persuasive intertwining of three evidential strands: the imagery itself, ethnography, and neuropsychology. This task has been notably achieved by David Whitley.17 He is today the most prolific, perceptive and innovative writer on North American rock art.

Whitley has shown that the old notion that North American ethnography is silent on the all-important question of who made rock art is incorrect. Earlier writers had either missed the sometimes subtle and metaphorical references or had simply been loath to spend the time necessary to explore the ethnography. The clues were there, waiting to be discerned. Dealing with the Columbia Plateau region alone, James Keyser and Whitley18 list 19 references in ethnographic reports to an association between rock art and shamanistic vision quests (solitary sojourns during which a person seeks a vision of a powergiving animal) and nine to shamans themselves making rock art. Similar evidence exists for other parts of the continent, especially in the west.

Without going into all the complex details of Native American indigenous religions in this part of the continent, I now focus on those components that are relevant to an understanding of rock art.19

Vision quests

Southern African San shamans do not seek out places for personal isolation to contact a spirit helper: they obtain their visions in sleep or during a trance dance. By contrast, vision questing is fundamental to native North American shamanistic religions, but not all vision quests are undertaken by shamans. As we shall see, people who are not shamans do, in some communities, seek power-bestowing visions in the same ways that shamans do. For an initial example, I turn to Åke Hultkranz20 who has described vision questing among the Wind River Shoshoni, a community who still live in some of their ancestral territories in the Wind River Valley and the Grand Teton, Wyoming. There is therefore a direct historical relationship between them and the rock art of that region.

At first, Hultkranz argued that power-bestowing visions were originally obtained in dreams, and that institutionalized vision quests were a later development. Subsequently, he accepted the evidence gathered by other ethnographers and agreed that vision questing has considerable time depth.21 Either way, the belief that visions may be obtained in dreams or during vision quests is not restricted to the Shoshoni: it is widespread in North America, and the Shoshoni example is typical of the general practice.

The principal aim of a vision quest is to ‘see’ a spirit animal that will become the quester’s animal-helper and source of his power. Amongst the Shoshoni, a suppliant desiring a vision mounts his horse and rides up into the hills where there are already rock art images. He washes, and clothed in only a blanket he lies down on a ledge below the images. His vision is induced by fasting, enduring cold and lack of sleep, and smoking hallucinogenic tobacco. Some reports say that it may take three or four days before a vision comes to the suppliant – if at all. It is hard to tell if the vision comes when the quester is awake or dreaming.22 Sometimes tobacco was smoked just prior to sleep: drug-induced hallucinations would thus be experienced during sleep.23 People may also experience spontaneous waking visions.

Significantly, the Shoshoni use the word navushieip to denote both dreaming and waking.24 This is also true of other groups, such as the Yokuts.25 Their divisions of the spectrum of consciousness thus accord dreaming the same status as waking for the reception of information. (In some parts of North America ‘waking visions’ are, however, discounted.) The dreams in which spirits appear are more vivid than other dreams; the Shoshoni say that they hold your attention and you cannot awake until they are over. Visions may be mercurial: for instance, a ‘lightning spirit’ may appear as a body of water, then like a human being, then like an animal. Often frightening animals come to threaten suppliants, and they must brave them if their power-giving spirit animal is to appear. During visions, questers feel that they leave their bodies – the sensation of out-of-body travel.

Throughout North America, this travel often involves entering a hole in the rock, passing though a tunnel, evading various monsters and seeing a spiritual personage, the Master of the Animals, and his creatures. After receiving power, the shaman may emerge from a different place, sometimes via a spring. Whitley remarks, ‘“Entering a cave” or rock was a metaphor for a shaman’s altered state; therefore, caves (and rocks more generally) were considered entrances or portals to the supernatural world.’ He adds that flight and entering a cloud were further metaphors for shamanistic travel. During vision quests, North American shamans sometimes bled from the nose and mouth.26 The parallels with the southern African accounts of extra-corporeal, hallucinatory travel are arresting. Entry into the rock, movement through a tunnel, encounters with spirits and animals, emergence elsewhere through water, flight, and nasal haemorrhaging are experiences common to both continents.

Some ethnographic reports indicate that Native American people believed that rock art images were made, not by the quester, but by spirits, commonly named as ‘water babies’, ‘rock babies’, or ‘mountain dwarves’. These spirits were especially powerful shamans’ spirit helpers; they could be seen only in an altered state of consciousness. A shaman was so intimately identified with his spirit helper that, as Whitley27 points out, to say that a rock art image was made by a ‘rock baby’ was the same as saying that the shaman himself made it. To illustrate this point Whitley cites Harold Driver:28 a Native American informant told Driver that rock art sites were created by shamans who ‘painted their spirits (anit) on rocks “to show themselves, to let people see what they had done”. The spirit must come first in a dream.’ 29

Maurice Zigmond30 found that, amongst the Kawaiisu of south-central California, it was believed that a spirit named Rock Baby dwelt in the rock and made rock paintings. If one returned to a rock art site and found that more images had appeared since one’s previous visit, they were said to be the handiwork of Rock Baby. If one touched a rock painting and then rubbed one’s eyes, sleeplessness and death could result. The images thus possessed inherent power, rather like those in southern Africa: they were not merely pictures.

As early as the 1870s, J. S. Denison reported that a Klamath man told him that rock paintings ‘were made by Indian doctors [shamans] and inspired fear of the doctor’s supernatural power’.31 Similarly, a 1900 report records that, among the Thompson, ‘rock paintings were made by noted shamans’, 32 and in the 1920s Glenn Ranck found that ‘[o]ne night a Wishram medicine man [shaman] used an unseen power to paint a pictograph during the night. He was found in a trance at the foot of the pictograph the next morning’.33 Such reports could be multiplied many times over: the link between North American shamans and rock art is indisputable. But that realization is only the beginning – not the end – of research.

Vision quests were not one-off affairs. Shamans usually repeated quests throughout their lives. They believed that their power could be increased in this way. When a shaman had received a vision in a dream, he awoke and concentrated on it so that he would not forget it. At dawn he went into the hill to experience more dreams. When he had received sufficient revelations, he entered his ‘shaman’s cache’ to converse with his spirit helper.

Shamans’ caves

The term ‘shaman’s cache’ was coined by Anna Gayton to denote Yokuts rock art sites;34 other Californian groups used the terms ‘doctor’s cave’, ‘spirit helpers’ cave’, and ‘shaman’s medicine house’. These caches were located in rock shelters or, where there are no shelters, on low ridges. The word ‘cache’ was suggested by the presence at these places of a shaman’s paraphernalia – his ritual costumes, talisman bundles, feathers and other accoutrements. The rock shelters were commonly embellished with rock art images.

In California, it seems that cache sites were individually owned and could be passed down from generation to generation. In the Great Basin, on the other hand, sites were used by many shamans. Some sites in this region became renowned for their power, and shamans still journey great distances to seek visions at them, sometimes from as far away as northern Utah.35 The principal motif in this area is the bighorn sheep, which was a spirit helper for rain shamans.

The actual cache was believed to be inside the rock, which would open to admit the shaman.Yokuts people said that the openings were invisible to nonshamans, no matter how carefully they searched for them.36 Not surprisingly, it was through such openings that vision questers entered the spiritual realm. Gayton, who worked among the Yokuts in the 1930s, described a vision quest at a cache:

When a man had dreamed sufficiently [in preparation for receiving power], all the animals of his moiety gathered on a hill near a cache. The man was there too, and the animals opened the [site], telling him to enter. He stayed in there for four days. No one knew where he was, and often people went in search of him. While he was in the [site] the animals told him what to do. They gave him songs and danced with him all night. They gave him his regalia: ‘this just appeared on him, nobody knew where it came from…’ At the end of four days, the animals sent him out….37

Just how the experience of entering the rock may be generated became evident to the American archaeologist Thor Conway when he was at a Californian rock art site known as Salinan Cave:

Red and black paintings surround two small holes bored into the side of the walls by natural forces. As you stare at these entrance ways to another realm, suddenly – and without voluntary control – the pictographs break the artificial visual reality that we assume…. Suddenly, the paintings encompassing the recessed pockets began to pulse, beckoning us inward. The added effects – a nighttime setting, firelight, shadows dancing on the walls, and the resonation of aboriginal chanting – could induce even more profound experiences.38

It is highly probable that those San paintings that seem to thread in and out of the walls of rock shelters similarly came to life and drew shamans through the ‘veil’ into the spirit realm.

Other reports show that a shaman’s cache site was also spoken of as mawyucan – ‘whirlwind place’ – because a shaman’s ability to fly was sometimes called ‘whirlwind power’. Among some groups the word for whirlwind was a synonym for spirit helper. In Sequoia National Park, in the southern Sierra Nevada, a rock art site was known as pahdin, which means ‘place to go under’, a reference to passing underwater and drowning.39

Comparison of these reports with K”au Giraffe’s account (Chapter 5) of how his helper came and took him underground and underwater, how he was taught to sing special songs, and how he experienced the presence of many animals reveals parallels that could be multiplied if we had the space to examine other North American reports – and, indeed, reports from elsewhere in the world. It is possible to discern in such accounts specific rationalizations of experiences generated by the neurology of the human brain in altered states of consciousness. I can think of no other way to explain the similarities: they are the product of the universal human nervous system in altered states of consciousness, culturally processed but none the less still recognizably deriving from the structure and electro-chemical functioning of the nervous system.

Puberty ceremonies

So far, I have focused on shamanistic visions. North American rock art is, however, also associated with another kind of vision quest. Among the Quinault of Puget Sound, boys made rock paintings of mythical water monsters that they saw in visions.40 In southern California, too, puberty ceremonies culminated in rock painting. During the southern California rituals, boys and girls learned religious and moral truths and correct behaviour. They also ingested hallucinogens, jimsonweed for the boys and tobacco for the girls. At the climax of the rituals the initiates took part in a race to a designated rock. The winner of the race was believed to enjoy longevity. After the race, the initiates made rock art images on the rock. Shamans supervised both the boys’ and the girls’ rituals.

The girls’ images comprised red geometric designs that included diamond chains and zigzags; both were said to represent rattlesnakes, culturally sanctioned spirit helpers for girls (Pl. 11). These designs corresponded to ones painted on the girls’ faces. Whitley found that the last such ceremony took place in the 1890s.41

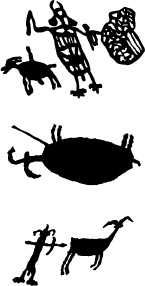

The boys’ initiation rituals had ceased earlier in the nineteenth century and are less well documented. Nevertheless, it seems that they followed the same pattern as the girls’ ceremony and also culminated in rock painting. One early account suggests that the boys’ motifs included circles, nested curves, and a human figure (Fig. 41).42

41 Western American rock art made as part of boys’ puberty rituals. The images differ from those made by girls in their puberty rituals.

A key aspect of these rituals is that the boys and girls focused on different entoptic phenomena. Both sexes would have had the neurological potential to see the full range of entoptics, and we may be fairly certain that the boys’ entoptic forms would have flashed in and out of the girls’ visions, and vice versa. But the guidance given by the shamans who were conducting the rituals encouraged each sex to focus on what were considered to be its appropriate images. The same gender distinction in motif-use is evident in baby cradleboard headcover designs; it was widely sanctioned and recognized.43

Again we see that the neuropsychological approach does not in any way suggest a mechanistic link between mental and painted images. Cultural interventions select items from the full repertoire of potential mental images, and this selection process takes place within a social community: the spectrum of consciousness is simply one of the raw materials that society uses to construct itself through the intervention of individuals.

Whitley points out that these puberty ceremonies were part and parcel of a shamanistic belief system. As I have noted, the ceremonies were overseen by powerful shamans who interacted with the initiates during their drug-induced trances to ensure that they experienced the culturally approved visions. Moreover, the initiates received spirit helpers during these rituals and then painted them on the rocks.

These parallels between the puberty rituals and vision quests explain why some researchers distinguish between ‘shamanic’ and ‘shamanistic’.44 For them, ‘shamanic’ denotes the behaviour and experiences of shamans; ‘shamanistic’, on the other hand, denotes a broader range of behaviour, as, for example, the role of shamans in some North American puberty rituals. It could be said that the San trance dance is ‘shamanic’ and the girls’ Eland Bull Dance is ‘shamanistic’. At the Eland Bull Dance, an old shaman mimes the mating behaviour of an eland bull, while the women mime that of eland cows. At the climax of the dance, the eponymous antelope is said to run up to the dancers. They are afraid, but the shaman taking the role of the eland bull reassures them: he says that this is a ‘good thing’ come from god.45 The appearance of the spirit eland is thus ‘shamanistic’ rather than specifically ‘shamanic’.

Metaphors in the brain

This brief overview does not take account of local variations in North American rock art motifs that may have had somewhat different, though probably related, meanings. Certainly, researchers should always guard against seeking similarities at the expense of dissimilarities.Yet the general association of much North American rock art with shamanistic visions should not be ignored. It provides a foundation for considering local variants. Moreover, the indisputable depiction of visions in North American (and San) rock art is clearly relevant to our exploration of Upper Palaeolithic art: the people who made North American (and southern African) rock art and those who made Upper Palaeolithic art had the same nervous systems.

As I have pointed out, some North American archaeologists have appreciated the value of multiple evidence and have begun to intertwine the ethnographic and neuropsychological evidential strands – with striking results. Whitley in particular has systematically applied the neuropsychological model (Chapter 4) to North American rock art.

He has shown that seven of the Stage 1 entoptic forms are present in the Great Basin rock art and elsewhere (grids, parallel lines, swarms of dots, zigzags, nested catenary curves, filigrees and spirals).46 Moreover, he has found evidence for all three stages of transition along the intensified trajectory of altered consciousness.47 It will be recalled that in Stage 1 subjects see entoptic phenomena; in Stage 2 they construe them as important objects; in Stage 3 they experience and participate in fully developed hallucinations, though entoptic elements may persist peripherally or integrated with visions of animals and people. Whitley reiterates an important point that Dowson and I made when we first formulated the neuropsychological model in 1988:48 ‘Without this model, features of the art (such as the common association and juxtaposition of geometric and representational motifs) would remain enigmatic’.49 He also notes that the close fit between the motifs suggested by the model (and derived from laboratory conditions) and those of the rock art provides an independent ‘scientific test of the rock art’s ethnographic interpretation – its origin in altered states of consciousness’.50

Taking this sort of comparison as a starting point, Whitley discusses the widely reported ways in which the visual, somatic and aural effects of altered states are construed in North America. He concludes that there is a ‘shamanistic symbolic repertoire’ that includes hallucinations of

– death/killing,

– aggression/fighting,

– drowning/going underwater,

– flight,

– sexual arousal/intercourse, and

– bodily transformation.

42 The killing of a bighorn sheep was associated with rain-making. When a shaman killed a sheep, he was, in effect, killing himself.

In this list, Whitley gathers together the ways of rationalizing altered states of consciousness that we have already discussed in earlier chapters and adds important new ones (Figs 42, 43). I briefly consider each in turn and note some parallels with the southern African San.

As in southern African San religion and art, so, too, in North America shamans are sometimes said to ‘die’ when they enter trance. ‘A shaman’s activities as a sorcerer, or his own conscious act of entry into the supernatural world, were a kind of “killing”.’ 51 Moreover, when a Numic rain shaman made rain he was said to have killed a bighorn sheep. That is, he killed himself because he was a bighorn sheep in the supernatural realm. Perhaps most interestingly, well over 95 per cent of the bighorn sheep engraved across the Mojave Desert have large, upraised tails – unlike the real animals which have small, pendant tails (Fig. 42). A bighorn sheep raises its tail in two circumstances: death and defecation. It therefore seems likely that virtually all the engravings of bighorn sheep depict dead or dying animals. Similarly, in southern Africa, many eland are depicted dead.When he was speaking to Joseph Orpen, the San man Qing said that the shamans were ‘spoilt’ – that is, they ‘died’ – at the same time as the elands and that it was the dances that caused this to happen to both men and antelope. Finally, in North America, nasal bleeding was commonly associated with physical death and entry into the spirit world, as it was in southern Africa.

The notion of aggression and fighting, Whitley’s second metaphor, is clearly related to the death metaphor. An association of fighting with North American shamans is, for instance, suggested by the Yokuts term tsesas which means spirit helper, shaman’s talisman, and stone knife.52 Moreover, among some south-central California groups the words for shaman, grizzly bear, and murderer were interchangeable.53 The potential violence of trance experience was manifest in the battles and fights that were sometimes seen by shamans in trance. In Native California rock art, people are shown shooting a symbolic arrow at others, and dangerous animals, such as rattlesnakes and grizzly bears, are painted at many sites. Most importantly, shamans are depicted bristling with weapons – bows, arrows, atlatls, spears and knives. In southern Africa comparable paintings of fights have been interpreted as records of bands defending their territories against invaders. But the San did not defend territories. Close inspection of these depictions often reveals details that indicate that the fight is actually taking place in the spirit realm.

Thirdly, drowning and passing underwater are themes that crop up in many North American shamans’ narratives. In the art, the experience is referred to by images of aquatic spirit helpers. They include water-striders, frogs, toads, turtles, beavers and swordfish (Fig. 43 D). Turtles were sometimes thought of as doors to the spirit world. We have seen that, in southern Africa, depictions of fish and eels often suggest subaquatic locations.

Fourthly, supernatural flight is ubiquitous in North American shamans’ narratives. In the art, shamans are depicted wearing quail feather topnots (Fig. 43 A). The quail was associated in a number of ways with shamans. For instance, the bowl used to prepare infusions of jimsonweed was called ‘quail’, and the Master of the Animals, whom shamans visited, was clothed in a quail feather cape.54 Shamans are also depicted with birds’ feet (Fig. 43 B, C). Sometimes, quails and other birds were depicted, often sitting on shamans’ heads. Whitley also argues that concentric circles, frequently associated with shamanistic figures, allude to flight and signify that he was a ‘concentrator of power’.55 In southern Africa, flight and birds are similarly often associated with images of shamans.56

Fifthly, sexual arousal is an important theme that Whitley adds to the list. In North America, supernatural power was associated with sexual potency, and shamans were believed to be especially virile. Rock art sites were symbolic vaginas, and entry into the wall of a rock art site was thus akin to intercourse. Sexual arousal and penal erections are associated with both altered states of consciousness and sleep. In southern Africa, a great many figures are ithyphallic. This feature has generally – and rather vaguely – been taken to refer to ‘masculinity’, but the painted contexts of the figures seems to confirm that, as in North America, sexual arousal was a metaphor for altered states of consciousness.

43 North American rock art images depicting shamanistic experience: A Flight; the figure wears a quail topknot; B and C Winged flight; D Underwater; a salamander swimming around a saltwater kelp plant; E Transformation of a shaman into a rattlesnake; rattlesnake shamans cured snake bites and controlled snakes.

Bodily transformation, Whitley’s last metaphor, is so common in both North America and southern Africa that it hardly needs further comment. On both continents, shamans fuse with animals and experience bodily distortions (Fig. 43E).

This list of metaphors – or rationalizations of altered states of consciousness – presents a mixture of somatic, aural, visual and mental experiences associated with trance. The similarities that I have outlined show that fundamental neurological events can be variously interpreted, but also that these events are nevertheless likely to be seen in certain ways. Underlying all these shamanistic experiences is the concept of supernatural power and the ways in which it can be harnessed in altered states of consciousness.

Quartz and supernatural power

One of the most fascinating findings to emerge from recent North American rock art research concerns a link between the way in which engravings were pecked, or hammered, into the rock and a manifestation of supernatural power. To demonstrate this link, Whitley and four of his associates focused on a Mojave Desert site known as Sally’s Rock Shelter. They found that pieces of quartz were scattered around the engraved rocks; they had been used as hammer-stones. Unmodified white quartz cobbles, approximately 12 cm (5 in) long, were also wedged in cracks between boulders (Pl. 10). It is common to find offerings of beads, sticks, arrows, seeds, berries and special stones at vision quest sites.

This is by no means the only rock art site associated with quartz; the stone is widely associated with shamanism. For instance, Bob Rabbit, the last known Numic rain-shaman, used quartz crystals in his weather-control ceremonies, and crystals were believed to be inhabited by spirits.57 More specifically, reports show that shamanistic vision questers in the Colorado Desert ‘would break up white quartz rocks, believing that the high spiritual power contained within these would be released to enter his or her body’.58 The scatter of quartz fragments at Sally’s Rock Shelter apparently resulted from this practice.

The reason for the practice of breaking open quartz seems to be that, when quartz stones are rubbed together, they generate a bright, lightning-like light. Triboluminescence, as this characteristic is known, became a manifestation of supernatural power. Although striking quartz against basalt in the act of making an image will not activate triboluminescence, the scatters of quartz fragments found at rock art sites suggest the importance of the mineral as intrinsically containing power. Here is another instance of rituals that were performed at rock art sites.

Images in society

An important point that emerges from this discussion and from Chapter 5 is that the insights of shamans are accepted by their communities. People who have never moved to the end of the intensified spectrum none the less believe in a tiered cosmos, accept that shamans are able to travel between its levels, and respect rock images (whether they are allowed to see them or not) as materializations of supernatural visions or dreams. Why are people so compliant? There are a number of reasons. For one, they have had some glimpse, some inkling, of the spirit world in their own dreams. In the absence of any knowledge of human neurology, dreams provide them with personal, indeed incontrovertible, evidence for the existence of a spiritual realm. This spirit world may be the preserve of the shamans, but it can unnervingly invade the minds of ordinary people. The whole of society is thus drawn into the shamanistic way of seeing things. Shamanism is not simply a component of society: on the contrary, shamanism, together with its tiered cosmos, can be said to be the overall framework of society.

In this context, we can enquire what impact rock art images had on Native North American communities. As yet, this is a line of research that has not been much followed in North America, though Whitley has explored the social role of shamanism and rock art in the western Great Basin.59 As we have seen, he has shown that killing a bighorn sheep was a metaphor for making rain. When the people of this region moved into an economy based on seed-gathering, rain-making assumed even more importance. This shift, Whitley argues, must be seen in the context of two systems of inequality: men over women, and shamans over non-shaman males. Rock art, Whitley argues, was implicated in efforts to maintain gender asymmetry and in the growing political organization of the region. Parallels with the roles of shamans and their rock art in southern Africa, especially during the socially turbulent times of the colonial period, are evident enough. Rock art becomes an instrument of social discrimination, as Max Raphael long ago argued was the case during the west European Upper Palaeolithic.

One of the most striking social differences between southern African and North American shamanism concerns secrecy. In southern Africa, the San are generally open about their beliefs. After shamanistic journeys to the spiritual realm and to other places on the level on which people live, shamans recount their experiences to everyone: all men, women and children are permitted to listen – indeed, everyone is eager to find out what is going on in the spiritual world. As Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd found in the nineteenth century, and as I and many anthropologists working in the twentieth- and twenty-firstcentury Kalahari Desert have found, the San are eager that everyone should know what they believe and experience. When I was in the Kalahari, some of the old Ju’/hoansi told Megan Biesele to check what I was writing down: they wanted the world to know everything.

By contrast, much shamanistic activity in North America was conducted in secrecy. The degree of secrecy varies from group to group. Working in 1948 among the Shoshoni, Hultkranz found that, although they were more open about their religious beliefs and experiences than the Plains Indians, they were reluctant to disclose the details of their visions except to close kin and friends.60 In the past, they also initiated hunts. Places where Shoshoni shamans obtain their visions are considered to be powerful, filled with spirits and best avoided.The Shoshoni were formerly nomadic, and sacred places are therefore scattered throughout their territory: there was a network of sacred places across the landscape.

North American shamans conducted their vision quests in remote places, far from ordinary social relations. Rock art sites were believed to be protected by supernatural powers, swarms of insects, and mysterious lights.61 If they were close to settlements, they were avoided by all who were not shamans. This seclusion set shamans apart, physically and symbolically, from ordinary people. They were reluctant to speak about what they ‘saw’ at these isolated places or to reveal the identity of their spirit helpers.62 This secrecy built up an aura of fear: people not only respected shamans, they also feared them. Knowledge is power. In the 1870s, Denison noted that Klamath shamans’ rock paintings ‘inspired fear of the doctor’s supernatural power’.63 Indeed, shamans had the ability to bring harm to people who disobeyed them or failed to observe religious rules. The images remained as incontrovertible signs of the shamans’ awesome power.

The sites themselves, the shamans’ caches, were perceived as places of great wealth by people who were not shamans. They emphasized the riches as well as the danger of such places. Whitley points out that non-shamans’ perceptions of caches ‘probably resulted from the tension between shamans and nonshamans, based on perceived material wealth, potential malevolence, and the sexually predatory nature of some shamans’.64 In this way, the material manifestations of shamans’ activities – rock art images and shamans’ caches – played a role in establishing social relations and making them appear part of the natural order of things. Beliefs about the power of the images, backed up by peoples’ own dreams, made the shamans’ powerful positions in society appear inevitable. By making powerful images derived from the spirit world, shamans were creating and establishing their social positions: they knew that the images would have the effect on others that they did in fact have. As with the San, North American rock images thus continued to play a role after they were made.

When Anna Gayton explored the relationship between Yokuts and Mono chiefs and shamans, she found a system of alliances between secular and spiritual authority.65 A chief could increase his wealth by a close relationship with a shaman, and the shaman, in turn, could claim the protection of his chief. Wealth derived largely from the annual mourning ceremony; rich people who declined to contribute to this occasion stood in danger of spiritual attack from the chief’s shaman. Conflict, sometimes internecine, between descent lineages also implicated both chiefs and shamans. Religion was certainly not separated from politics and jockeying for power.

Was this kind of relationship, together with the continuing social impact of rock art images long after they had been made, also true, we may now ask, of the hidden, subterranean images of Upper Palaeolithic western Europe? Was Upper Palaeolithic religion also implicated in political affairs? To begin to answer this question, we need to take a step back to the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic Transition and think about the circumstances in which human beings began to make pictures in the first place.