CHAPTER 7

An Origin of Image-Making

Case studies, such as the two in Chapters 5 and 6, greatly enrich our understanding of the ways in which human beings not merely cope with but also actively exploit the full spectrum of shifting consciousness. Ethnography puts flesh and life on the skeleton – the framework – that neuropsychology provides. But even the two studies that I have presented show that simple, one-off ethnographic analogies may be decidedly misleading. The solitary vision quest, for instance, that is so important in North American shamanism is absent from its southern African San counterpart, and this difference points to different social relations between shamans and their communities.

Above all, we see that intelligence is no doubt important.But it is in the ways in which people understand shifting consciousness that cosmology, experiences of cosmology, concepts of supernatural realms, and art all come together. When we move to the Upper Palaeolithic, there is, of course, no ethnography, and we have, as it were, to re-arrange our evidential strands.

Interlocking change

Perhaps the most striking feature of the west European Upper Palaeolithic, one on which many writers comment, is a sharp increase in the rate of change. Compared with the preceding Middle Palaeolithic, a great deal happened in a comparatively short time. We have noted greater diversity in the kinds of raw materials used for artefact manufacture, the appearance of new tool types, the development of regional tool styles, socially and cognitively more sophisticated hunting strategies, organized settlement patterns, and extensive trade in ‘special’ items. Even more striking is the explosion of body decoration, elaborate burials with grave goods, and, of course, portable and parietal images. It is clear that all these areas of change were interdependent – they interlocked. They were not a scatter of disparate ‘inventions’ made by especially intelligent individuals; rather, they were part of the very fabric of a dynamic society. At the same time, archaeological evidence suggests that they did not interlock in the sense that they constituted an indivisible package (Chapter 3). The west European Upper Palaeolithic was certainly not a period of social, technological and conceptual stasis. There can be no doubt that significant, allembracing change was at last on the march.1

An implication of this new dynamic is that the Upper Palaeolithic was a period of social diversity, a time when social distinctions and social tensions proliferated and came to be the driving force within society.

If we are to seek a driving mechanism for the west European ‘Creative Explosion’, it must be in social diversity and change. This means that we need to consider the divisive functions of image-making. In doing so, we distance ourselves from earlier functionalist explanations, such as art for art’s sake, sympathetic magic, binary mythograms, and information exchange, all of which see art as contributing to social stability. Instead, we follow up and develop Max Raphael’s ideas. It was he who said that Upper Palaeolithic communities were ‘history-making peoples par excellence’;2 he realized that their art was not simply an idyllic expression of contentment, an efflorescence of a ‘higher’ aesthetic sense, but rather an arena of struggle and contestation.

To understand how image-making could be born in social contestation I return to the notions of consciousness that I developed in earlier chapters and introduce two new concepts: fully human and pre-human consciousness.

Consciousness and mental imagery

I have pointed out that the making of images of animals and people could not have developed out of, say, body painting. The notion that an image is a scale model of something else (say, a horse) requires a different set of mental events and conventions from those that perceive the social symbolism of red marks on someone’s chest. Body decoration did not evolve – could not have evolved – into image-making. Art historians have given much attention to the ways in which graphic imagery is perceived as commensurate with mental imagery and objects in the world; scale, perspective, and the selection of distinguishing features are just some of the ideas that they discuss. Whilst these notions help to explain how people today interpret a pattern of lines on a surface as an image of something other than itself, they do not explain how people first came to believe that such marks could call to mind a bison, a horse or a woolly mammoth – if indeed they did.

As may be expected, the Abbé Henri Breuil held strong views on the question of the origins of art. All his ideas were based on the innatist position. In Chapter 2, we saw some of the limitations of the notion that human beings have an innate artistic drive and that this characteristic of their minds leads, almost forces, them to make pictures. Breuil called this supposed urge ‘the artistic temperament with its adoration of Beauty’.3 But he also tackled the problem in more practical terms, wondering how people first thought of making representational images. One of his suggestions was that images evolved from masks, though exactly how this could have happened he did not say. A more influential notion of his was that people suddenly discerned the outline of, say, a horse in natural marks on the wall of a rock shelter. At once, they realized that they could make such marks themselves – and not only of horses but of other animals as well. Breuil also pointed to the so-called ‘macaronis’, arabesques and meanders that Upper Palaeolithic people made with their fingers in the soft mud on cave walls. In amongst these apparently idle loops and marks, according to Breuil, people discerned parts of animals and realized that they could make pictures in this way. Then, alongside natural marks and ‘macaronis’, Breuil placed handprints and argued that these marks in some way evolved into representational images of animals, though exactly how and what the intermediate stages were he did not explain.

Then there is the short-cut explanation for the origin of image-making that does not require pre-existent marks or ‘macaronis’. Suddenly, some exceptionally intelligent person simply invented picture-making. At once, the idea caught on, and others started making their own images of animals. French archaeologists and cave art specialists Brigitte and Giles Delluc sum up this position:

Around 30,000 years ago, in the Aurignacian, at the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic, someone or some group in the Eyzies region invented drawing, the representation in two dimensions on the flat of the stone of what appeared in the environment in three dimensions.4

There are serious problems with all these still-popular and widely published explanations. First, the evidence of the caves suggests that ‘macaronis’ were not the first wall markings; they were made throughout the Upper Palaeolithic. Secondly, the explanations are often couched in the plural: ‘people suddenly discerned…’ But what is really meant here is that especially bright individuals (as the Dellucs allow) here and there in western Europe invented imagery or spotted a resemblance between the natural marks or ‘macaronis’ and an animal and then told others about it. But why did an individual examine marks and ‘macaronis’ so closely if he or she did not have some prior expectation of what might be found in them? Even allowing for the effectiveness of a chance, serendipitous glance of a twenty-first-century Westerner at, say, damp marks on a wall, we must say that one cannot ‘notice’ a representational image in a mass of lines unless one already has a notion of images. And such a notion must be socially held; it cannot be the exclusive property of an individual.

There is good reason for coming to this conclusion. Indeed, Breuil himself relates a tale that counts against his own explanation. He says that Salomon Reinach, the writer who early on propagated the idea of sympathetic magic, found that a Turkish officer whom he met when he was a student in Athens was incapable of recognizing a drawing of a horse ‘because he could not move round it’.5 Islam, of course, forbids the making of representational images. Being a Muslim, the officer was entirely unfamiliar with representational pictures.

The anthropologist Anthony Forge discovered the same sort of thing when he was working amongst the Abelam of New Guinea. He found that these people make three-dimensional carvings of spirits and also paint bright, twodimensional, polychrome spirit motifs on their ritual structures. Although the motif itself is essentially the same in both cases, the two-dimensional versions arrange the elements in different ways; for example, the arms may emanate from beneath the noses of the figures whereas the three-dimensional carvings have the arms in the usual place. Why do the Abelam not find this difference strange? The answer to this question is that neither the three- nor the two-dimensional versions are representations: they do not show what the spirits look like; rather they are avatars of the spirits. ‘There is no sense, ’ Forge found, ‘in which the painting on the flat is a projection of the carving or an attempt to represent the three-dimensional object in two dimensions.’ 6 The paintings are not meant to ‘look like’ something in nature, as we so easily assume.

As a result of their understanding of the non-representational nature of painting, the Abelam had difficulty in ‘seeing’ photographs.7 If they were shown a photograph of a person standing rigidly face-on, they could appreciate what was shown. But if the photograph showed the person in action or in any other pose than looking directly at the camera, they were at a loss. Sometimes Forge had to draw a thick line around the person in a photograph so that people could retain their ‘seeing’ of him or her. This is not to say that the Abelam are inherently incapable of understanding photographs. Forge managed to teach some Abelam boys to understand the conventions of photographs in a few hours, but up until his tuition, ‘seeing’ photographs was not one of their skills. As Forge puts it, ‘Their vision has been socialized in a way that makes photographs especially incomprehensible.’ 8

‘Seeing’ two-dimensional images is therefore something that we learn to do; it is not an inevitable part of being human. How, then, could Upper Palaeolithic people ‘see’ images in the convolutions of ‘macaronis’ unless they already had a notion of such imagery?

Despite this (to my mind insuperable) difficulty, writers have persisted in trying to get around the problem because they can conceive of no other way in which people could have stumbled upon the notion of two-dimensional images on cave walls. The most ingenious – and complex – attempt has come from the art historian Whitney Davis.9

Davis fully understands the fundamental problem of assuming that, in dealing with the earliest Aurignacian images, we are in fact dealing with images. As Forge succinctly puts it when writing about the Abelam, ‘We must beware of assuming that they see what we see and vice versa.’ This is the crux of the matter. Then, too, Davis rightly rejects the notion that an evolving ‘aesthetic sensibility’ led to image-making.10 But he finds no option other than (a) to proceed as if Upper Palaeolithic images were representations of things in real, material life and (b) to assume that two-dimensional image recognition evolved inevitably.

At the risk of over-simplifying his work, we can say that, although he rejects the origin of images in ‘macaronis’, he argues that people made random ‘marks’, even during the Middle Palaeolithic. But, at first, they did not adopt a ‘seeing-as’ approach to their handiwork; that is, they did not see the marks as representing something else. If we allow this idea of random scratches, where do we go from there? It is at this point that it seems to me that Davis’s line of reasoning is stymied. He writes:

Continually marking the world will continually increase the probability that marks will be seen as things. Eventually very complex clusters of marks – it does not matter whether they are intentionally clustered or just happen to be seen together – will result in occasional perceptual interpretations of marks as very complex things, such as the closed contours of natural objects. The manufacture of marks on surfaces and all manner of other activities, from body ornament to building, potentially add marks and colour patches to the world. In sum, the emergence of representation is the predictable logical and perceptual consequence of the increasing elaboration of the man-made visual world [Davis’s emphasis].11

As James Faris, in a comment on Davis’s argument, pointed out, the art historian is saying that the discovery of image-making in random lines was inevitable.12 Given long enough, people just had to tumble to the potential of image-making. Davis has substituted inevitability for serendipity. Faris made another key point when he asked: ‘Why these images rather than, say, plants or small animals, and why not suns or snakes or faces…?’ In other words, why this particular motivic vocabulary of bison, horses, aurochs, mammoths, and so forth? Although there are parietal images of, for instance, hyenas, owls and fish, they are very rare indeed. There must therefore have been presuppositions in the Upper Palaeolithic minds; they were ‘looking for’ certain things and not others. However we explain the origin of the conventions of representation, we are left with the key thought that a vocabulary of motifs existed in people’s minds before they made images. They did not begin by making a wide range of motifs – anything an individual image-maker may have wished to draw – and then focus on the limited range of motifs. Why? The inevitabilist argument begs this awkward question.

Finally, even if all this were to have happened and some clever Upper Palaeolithic people did ‘invent’ two-dimensional imagery, society at large would need to have had some reason for wanting to make more images, and, moreover, images from the predetermined vocabulary. It follows that images must have had some pre-existing, shared value for people, first, for them to notice them at all, and, secondly, to want to go on making them. That is, images of a specific set of animals must have had some a priori value for people to take any interest in them. A chicken or egg problem, if there ever was one, but, as we shall see, it takes us to the heart of the matter.

How, then, did people invent two-dimensional images? We seem to have reached an impasse in our attempts to answer this question. The difficulty, however, lies more with the question itself than our ability to answer it. It presupposes a specific type of answer – the wrong type of answer.

In short, people did not invent two-dimensional images of things in their material environment. On the contrary, a notion of images and the vocabulary of motifswere part of their experiencebefore they made parietal or portable images.

To explain this apparently contradictory yet, I believe, crucial point we need to return once more to the spectrum of human consciousness and see how it came to assume the form that it now has and that it had for Homo sapiens at the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic.

The neurobiology of primary and higher-order consciousness

In some sense, consciousness is the last frontier. If researchers wish to go boldly (the famous Star Trek split infinitive is indefensible) where no one has gone before, consciousness is a favoured launch-pad to fame. Consciousness is the struggle of the moment, and there is no shortage of protagonists. It is not my purpose to review so complex and disputatious a field. Instead, I turn to the researcher whom I consider most relevant to our more modest quest to understand Upper Palaeolithic image-making.

Gerald Edelman won the 1972 Nobel Prize for his work in immunology. Then he reached out for the prize of ‘consciousness explained’. Soon after winning the Nobel Prize, he began to see that recognition in the brain was rather like recognition in the immune system. He is now Director of the Neurosciences Institute and President of the Neurosciences Research Foundation.13 To study the origins of consciousness, he realized, one had to combine a study of the anatomy of the brain with Darwin’s theory of natural selection. He therefore wholeheartedly embraced the belief that mind and consciousness are the products of matter, the matter that we call brain. There is no place in his work for Descartes’s dualism. Nor is there room for pessimism: he rejects the notion that you cannot use consciousness to explain consciousness – that the task is too difficult. Consciousness has evolved biologically and can therefore be explained biologically. The dense neural link-ups in the brain are not like a programmed computer, nor like the chapels of a cathedral, with or without interconnections, nor like a Swiss army knife; they are more open-ended than any of these similes suggest.

Still, there is a lacuna in Edelman’s work. Let me say at once that it is by no means a fatal flaw, and later I try to fill it within the framework that he has developed. The problem is that he concentrates on the ‘alert’ end of the spectrum of consciousness and overlooks the autistic end. But, as I say, this is a deficiency that can be rectified – and he has himself supplied the tools for the job.

When it comes to discriminating between acceptable and non-acceptable hypotheses, Edelman is explicit: he realizes that researchers must make their methodological criteria plain – as I have tried to do at a number of points in this book. Rightly, I believe, Edelman insists that any explanation of consciousness must be based on observable phenomena and be related to the functions of the brain and body. If an explanation is to be based on evolution, an anatomical foundation is essential. That is to say, an explanatory theory of consciousness must propose ‘explicit neural models’ that explain how consciousness arose during evolution. Moreover, any explanation must advance ‘stringent tests for the models it proposes in terms of neurobiological facts’. Finally, the explanation must be ‘consistent with presently known scientific observations from whatever field of enquiry and, above all, with those from brain science’.14 Edelman is here summarizing some of the criteria for evaluating hypotheses that I noted in Chapter 2.

But what is the basic neurology of the brain? All neurobiologists accept that the fundamental cell type in the brain is the neuron. Neurons are connected to other neurons by synapses. These connections are facilitated by the generation of neurotransmitters, chemical substances that allow electrical impulses to cross over from one neuron to another. The cerebral cortex, the outer ‘skin’ of the brain, contains as many as ten billion neurons. This complexity is daunting. Yet it is out of complex interactions between the billions of neurons that consciousness arises.

Next, we need to distinguish between the limbic system and the thalamocortical system. Both are made up of neurons, but they differ in their organization. The limbic system is concerned with fundamental, non-rational behaviours: appetite, sexual behaviour and defensive behaviour. It is extensively connected to many different body organs and the autonomic nervous system. It thus regulates breathing, digestion, sleep cycles, and so on. The limbic system evolved early to regulate the functioning of the body. By contrast, the thalamocortical system evolved to make sense of complex inputs from outside the body. It comprises the thalamus, a central brain structure that connects sensory and other brain signals to the cortex, and the cortex itself. The thalamocortical system developed after the limbic system and became intimately linked to it.

If we do full justice to Edelman’s ideas, we shall have no space over to discuss Upper Palaeolithic image-making. Let us therefore move on to Edelman’s identification of two kinds of consciousness: primary consciousness and higher-order consciousness.

Primary consciousness is experienced to some degree by some animals, such as (almost certainly) chimpanzees, (probably) most mammals, and some birds, but (probably) not reptiles. This is how Edelman defines primary consciousness:

Primary consciousness is a state of being aware of things in the world – of having mental images in the present.But it is not accompanied by any sense of a person with a past and future… [Primary consciousness depends on] a special reentrant circuit that emerged during evolution as a new component of neuroanatomy… As human beings possessing higher-order consciousness, we experience primary consciousness as a ‘picture’ or a ‘mental image’ of ongoing categorized events… Primary consciousness is a kind of ‘remembered present’… It is limited to a small memorial interval around a time chunk I call the present. It lacks an explicit notion or a concept of a personal self, and it does not afford the ability to model the past or the future as part of a correlated scene.

An animal with primary consciousness sees the room the way that a beam of light illuminates it. Only that which is in the beam is explicitly in the remembered present; all else is darkness. This does not mean that an animal with primary consciousness cannot have long-term memory or act on it. Obviously it can, but it cannot, in general, be aware of that memory or plan an extended future for itself based on that memory… Creatures with primary consciousness, while possessing mental images, have no capacity to view those images from the vantage point of a socially constructed self.15

Before pointing out the relevance of this sort of consciousness to the Transition, I give Edelman’s summary of higher-order consciousness. It is the kind of consciousness that Homo sapiens possesses:

Higher-order consciousness involves the recognition by a thinking subject of his or her own acts or affections. It embodies a model of the personal, and of the past and future as well as the present… It is what we as humans have in addition to primary consciousness. We are conscious of being conscious… How can the tyranny of the remembered present be broken? The answer is: By the evolution of new forms of symbolic memory and new systems serving social communication and transmission. In its most developed form, this means the evolutionary capacity for language. Inasmuch as human beings are the only species with language, it also means that higher-order consciousness has flowered in our species…

[Higher-order consciousness] involves the ability to construct a socially based selfhood, to model the world in terms of the past and the future, and to be directly aware. Without a symbolic memory, these abilities cannot develop… Long-term storage of symbolic relations, acquired through interactions with other individuals of the same species, is critical to self-concept.16

As I have said, Edelman explains the evolution of higher-order consciousness in neurobiological terms, but we need not consider all the details here. Higher-order consciousness sits, as it were, on the shoulders of primary consciousness. Simply put, the development was enabled by the evolution of enormously complex re-entry neural circuits in the brain. These circuits created more efficient kinds of memory. Indeed, the difference between primary consciousness and higher-order consciousness is that members of the species Homo sapiens, the only species that has it, can remember better and use memory to fashion their own individual identities and mental ‘scenes’ of past, present and future events. This is the key point.

It is also true that fully modern language is a sine qua non for higher-order consciousness. A corollary to this observation is that language makes possible auditory hallucinations: it is only with language that ‘inner voices’ can tell people what to do. In this way, visual hallucinations acquire a new dimension: they speak to those who experience them. Not only do shamans ‘see’ their animal spirit helpers; the spirits also talk to them.

When did this transition from one kind of consciousness to another take place? Edelman believes that higher-order consciousness evolved rapidly, though he does not hazard an estimate in years. In fact, relatively few gene mutations are required to bring about relatively large changes (new memory and re-entry circuits) in the brain. But Edelman refuses to be drawn on just when the change took place.

The Middle to Upper Palaeolithic Transition reconsidered

For the purposes of my argument, and bearing in mind the recent research that I outlined in Chapters 3 and 4, I believe it is reasonable to assume that higher-order consciousness developed neurologically in Africa before the second wave of emigration to the Middle East and Europe. The pattern of modern human behaviour that higher-order consciousness made possible was put together piecemeal and intermittently in Africa. Now the jigsaw pieces of previous chapters begin to fall into place. It seems likely that fully modern language and higher-order consciousness were, as Edelman argues, linked: it is impossible to have one without the other. This is a point that some researchers into the origins of language do not appreciate. When we speak of the acquisition of fully modern language, we are in effect also speaking of the evolution of higher-order consciousness.

In sum, in western Europe at the time of the Transition, the Neanderthals, descendants of the first out-of-Africa emigration, had a form of primary consciousness and the Homo sapiens communities had higher-order consciousness. This hypothesis clarifies a number of puzzling issues.

First, it explains why the Neanderthals were able to borrow certain things from their new neighbours but not others. Because their consciousness and form of language were essentially confined to ‘the remembered present’, Neanderthals could learn how to make fine blades but they could not conceive of a spirit world to which people went after death. Nor could they conceive of social distinctions that depended on categorizations of generations, past, present and future. Elaborate burials with grave goods were therefore meaningless, though immediate burial may not have been. Carefully planned hunting strategies that foresaw the migration of herds at particular times and places and required complex planning were also impossible. All in all, social hierarchies that extended beyond the immediate present (in which strength and gender ruled) were beyond their ken. They could learn some things but not others. As Edelman describes it, primary consciousness seems to fit what we know about the Neanderthals.

Secondly, and perhaps even more significantly, the shift from primary to higher-order consciousness facilitated a different experience and socially agreed apprehension of the spectrum of human consciousness. Improved memory made possible the long-term recollection of dreams and visions and the construction of those recollections into a spirit world. Simultaneously, the wider range of consciousness afforded a new instrument for social discrimination that was not tied to strength and gender. This is the part of the picture that Edelman does not consider in any depth, though he wonders if what he calls the abandonment of higher-order consciousness is what mystics seek.17 Mystics are people who exploit the autistic end of the spectrum of consciousness not only for their personal gratification but also to set themselves apart from others.

Sleep, dreaming and the activity of the brain in altered states of consciousness are part and parcel of the electro-chemical functioning of the neurons. Dreaming takes place during ‘rapid eye movement’ (REM) sleep. This state occurs for about one and a half to two hours during a good night’s sleep. It seems that all mammals experience REM sleep and probably dreaming; reptiles, which have a more primitive nervous system, do not. A human foetus at 26 weeks spends all its time in REM sleep. It therefore seems probable that dreaming is something that came about when, during evolution, the early limbic system became fully articulated with the evolving thalamocortical system.

Some researchers believe that dreaming is what happens when sensory input to the brain is greatly diminished: the brain then ‘freewheels’, synapses firing more or less at random, and the brain tries to make sense of the resultant stream of images. Be that as it may, we still need to ask if sleep is of any value to people and certain animals; if it is not, why did it evolve? After all, chances of survival in a hostile environment are reduced by sleep. The answer is that, in deep sleep, the brain manufactures proteins at a faster rate than during waking. Proteins are essential for maintaining the functioning of cells, including neurons, and in sleep, the human body builds up a reserve of proteins.18 Sleep (together with the dreaming that takes place in REM sleep, the prelude and postlude to deep sleep) is therefore biologically, rather than psychologically, important, and the brain evolved in such a way as to facilitate sleep for good biological reasons. There was no evolutionary selection for dreaming as such – only for the manufacture of proteins. Dreaming is a non-adaptive, but not maladaptive, by-product. The content of the dreams themselves is not significant. Yet people have always felt it necessary to ‘explain’ dreams, be it as voices of the gods or invasions by devils. More modern dream analysis by Freudians and Jungians is simply a contemporary way of giving meaning to dreams. It is, in the strict sense of the word, a modern myth that tries to make sense of a human experience that does not require that sort of explanation.

Now, as I have pointed out, it seems that dogs and other animals dream. This can be determined by observing their behaviour and by EEG studies.19 But – and this is the key point – they do not remember their dreams, nor do they share their dreams. With only a limited form of primary consciousness at their disposal, we can now see why this must be so, whether they have a simple form of communication or not. Human beings, on the other hand, can remember their dreams and are able to converse with one another about them. They are thus able to socialize dreaming: people in a given community agree, more or less, what dreaming is all about.

This point again brings us back to the spectrum of human consciousness. People have no option but to socialize the autistic end of the spectrum. They place value on some of its experiences in accordance with socially constructed concepts about dreaming. This is also true of states on the intensified, induced trajectory – visions and hallucinations. These experiences are possible because, with higher-order consciousness, people are able to remember them and, with fully modern language, to speak about them. Dreams and visions are thus inevitably drawn into the socializing of the self and into concepts of what it is to be human, concepts that change through time.

By this argument, Homo sapiens could dream, as we understand the term, and speak about dreams, but Neanderthals could not: they, with their particular level of primary consciousness, could not remember their dreams, though they must have passed though periods of REM sleep. Nor could they apprehend visions, even if some Homo sapiens neighbours showed them how to induce altered states of consciousness, and, even if they managed to enter an altered state (which they probably could do), they would have had no significant recollection of what happened during it.

It was, I argue, this distinction between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals that was a pivotal factor in the relationships between the two species and in triggering and driving the efflorescence of image-making that started at the Transition and, long after the Neanderthals had gone, spiralled through the rest of the Upper Palaeolithic.Homo sapiens communities saw that they had an ability that Neanderthals did not have: Neanderthals were congenital atheists. Homo sapiens’ more advanced ability in this mental arena may have made it important for them to cultivate the distinction by (in part) manifesting their visions as two- and three-dimensional images.

How, then, does this understanding answer the question with which this chapter began? How did human beings come to realize that marks on a plane surface or a carved three-dimensional piece of bone could stand for an animal?

Two-dimensional images

The answer lies partly in the ability to recall and socialize dreams and visions and partly in a specific characteristic of the visual images experienced in altered states of consciousness.

In the late 1920s, Heinrich Klüver found that both the entoptic elements from what I have called Stage 1 altered consciousness and the iconic mental images of animals and so forth from Stage 3 seem to be localized on walls, ceilings or other surfaces.20 This is a common experience and these images have been described as ‘pictures painted before your imagination’ 21 and as ‘a motion picture or a slide show’.22 Klüver also found that images (what are called ‘afterimages’) recurred after he had awakened from an altered state and that they too were projected onto the ceiling.23 These afterimages may remain suspended in one’s vision for a minute or more. Reichel-Dolmatoff confirmed this experience: the Tukano see their mental images projected onto plane surfaces, and, as afterimages, they can recur in this way for several months.24 We thus have a range of circumstances in which mental images are projected on to surfaces ‘like a motion picture or slide show’. It can happen while a person is actually in an altered state, or it can happen, unexpectedly, as uncalled-for afterimages, flash-backs to earlier altered states of consciousness.

Once human beings had developed higher-order consciousness, they had the ability to see mental images projected onto surfaces and to experience afterimages. Here, I suggest, is the answer to the conundrum of two-dimensional images. People did not ‘invent’ two-dimensional images; nor did they discover them in natural marks and ‘macaronis’. On the contrary, their world was already invested with two-dimensional images; such images were a product of the functioning of the human nervous system in altered states of consciousness and in the context of higher-order consciousness.

Because communities need to reach some sort of consensus about the full spectrum of consciousness, including altered states, and come to some understanding of the significance of moving along it, they would already have developed a set of socially shared mental images, which were to become the repertoire of Upper Palaeolithic motifs, long before they started to make graphic images. This prior formulation explains why the repertoire of motifs seems to have been established right from the beginning of the Transition in western Europe (though emphases within the repertoire changed through time and space).25 There was not a period during which individuals made whatever images they wished, followed by a period of more restricted socialized imagery. Nor is there any evidence for an early phase of random mark-making. In any event, image-making is not an essential feature of a shamanistic society: for instance, the San communities that today live in the Kalahari Desert (and have lived there for millennia) do not have a tradition of painting. There are no rocks in that sandy waste on which they could make images. Yet, despite a measure of idiosyncrasy, they do have a repertoire of animals that they ‘see’ in trance and a limited number of experiences that they expect to have in the spirit world. It is the entertaining and socializing of mental imagery that is fundamental to shamanistic societies. The imagery does not have to be expressed graphically.

How, then, did people come to make representational images of animals and so forth out of projected mental imagery? I argue that at a given time, and for social reasons, the projected images of altered states were insufficient and people needed to ‘fix’ their visions. They reached out to their emotionally charged visions and tried to touch them, to hold them in place, perhaps on soft surfaces and with their fingers. They were not inventing images. They were merely touching what was already there.

The first two-dimensional images were thus not two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional things in the material world, as researchers have always assumed. Rather, they were ‘fixed’ mental images. In all probability the makers did not suppose that they ‘stood for’real animals, any more than the Abelam think that their painted and carved images represent things in the material world. If we could be transported back to the very beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic so that we could compliment a painter on the ‘realism’ of his or her picture, I believe we should have been met with incredulity. ‘But, ’ the painter might have replied, ‘that is not a real bison: you can’t walk around it; and it is too small. That is a “vision”, a “spirit bison”. There is nothing “real” about it.’ For the makers, the paintings and engravings were visions, not representations of visions – as indeed was the case for the southern African San and the North American shamans (Chapters 5 and 6).

I do not argue that people ‘fixed’ their projected visions while in a deeply altered state of consciousness. If the vision seekers were cataleptic or ‘unconscious’, they could not have made images on the walls of caves. But, as we have seen, there are states in which one can move around and relate to one’s surroundings, even though one is seeing visions. Vision seekers would have been able to reach out to visions while they were in lighter states, experiencing afterimages, or, having shifted to a more alert state, they were trying to reconstitute their visions on the surfaces where they had seen them floating.

Further support for this view comes from Upper Palaeolithic parietal images themselves: they have a number of characteristics in common with the imagery of altered states of consciousness. For instance, the parietal images are disengaged from any sort of natural setting. In only a very few cases (e.g., Rouffignac Cave) is there any suggestion of what might possibly be a ground line (a natural stain on the rock wall): there is no suggestion of the kind of environment in which real animals live – no trees, rivers, or grassy plains. Moreover, Upper Palaeolithic parietal images have what Halverson perceptively called their ‘own free-floating existence’. They are placed ‘without regard to size or position relative to one another’.26 These characteristics are exactly what one would expect of projected, fixed, mental images that accumulated over a period of time. Mental images float freely and independently of any natural environment.

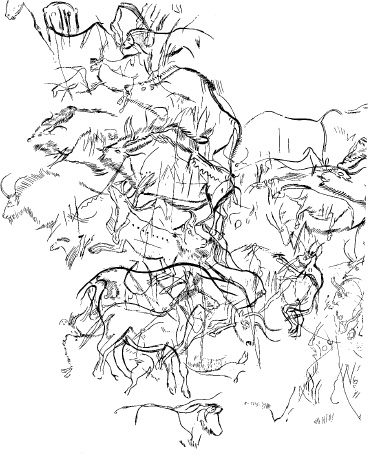

The impression of floating is sometimes enhanced by two further characteristics. Often, Upper Palaeolithic parietal images of animals have no hoofs; the legs terminate open-endedly in a way that suggested to some early researchers that the image-makers were depicting animals standing in grass that concealed their hoofs – but, of course, no grass is ever shown (Pl. 12). Other researchers have suggested that the animals may be depicted as dead, but more often than not they are clearly alive. It is more reasonable to suppose that the absence of hoofs implies an absence of ‘standing’. Then, too, when hoofs are depicted, they are sometimes in a hanging, rather than standing, position (Pl. 13). In Lascaux and other sites, hoofs are depicted to show their underside, or hoofprint. The combined effect of these features is particularly powerful in the Axial Gallery at Lascaux, where the images seem to float up the walls and over the ceiling, thus creating a tunnel of floating, encircling images (Chapter 9), or in the densely engraved panel in the Sanctuary at Les Trois Frères (Fig. 44) .

This is not to say that all Upper Palaeolithic depictions are images fixed in altered states of consciousness or while experiencing afterimages. Once the initial step had been taken, the development of Upper Palaeolithic art probably followed three courses. One stream continued to comprise mental imagery fixed while it was being experienced. A second stream derived from recollected mental imagery: after recovering from the experience, people tried to reconstitute their visions by closely examining the surface on which they had floated. They not only looked closely at the rock wall or ceiling; they also felt its contours and protuberances. Sometimes, they needed only to add a few lines, perhaps legs and an underbelly, to complete the vision/image that was, for them, inherently in the rock surface. A third stream derived from contemplation of the graphic products of the first two streams and the realization that someone who had never experienced an altered state could duplicate them. Many shamans believe that spirit animals, the ones that they see in their visions, also mingle with herds of real animals; there was therefore a link between spirit and real animals. In some cases, large depictions of animals, whether real or spirit animals, were communally produced: although one person may have been responsible for deciding on the subject matter and, perhaps, the general outline, a number of people co-operated to make the image.

44 Portion of the densely engraved panel in the Sanctuary in Les Trois Frères. The so-called musical bow player with a bison head is in the lower right of the copy.

These momentous steps were taken during a time of social change and differentiation. Higher-order consciousness allowed a group of people within a larger community to commandeer the experiences of altered consciousness and to set themselves apart from those who, for whatever reasons, did not have those experiences.The far end of the intensified spectrum became the preserve of those who mastered the techniques necessary to access visions. Although all people have the neurobiological potential to enter altered states of consciousness, those states are not socially open to all.

The spectrum of human consciousness thus became an instrument of social discrimination – not the only one, but a significant one. Its importance lay in the way in which the socializing of the spectrum gave rise to imagemaking. Because image-making was related, at least initially, to the fixing of visions, art (to revert to the broad term) and religion were simultaneously born in a process of social stratification. Art and religion were therefore socially divisive.

At first glance, one may be alarmed by such a grim thought and conclude that, because art and religion did not contribute directly to social cohesion in an all-embracing, functionalist way, they would not have lasted long. On the contrary, it was the very social discriminations that the process of dividing up the spectrum created that drove society forward. Social divisions are not necessarily maladaptive; indeed, they facilitate complex social adaptations to environments.

Three-dimensional images

I have dealt extensively with two-dimensional imagery because our interest is primarily in Upper Palaeolithic parietal art and the use that the people of that time made of the caves. We must, however, also consider three-dimensional imagery, the portable art that I described in Chapter 1.

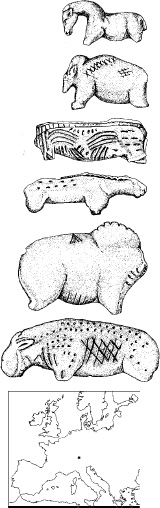

The earliest three-dimensional imagery was found in Aurignacian strata in southern Germany.27 The pieces come from open rock shelters, not deep caves. Radiocarbon dates for the four sites are as follows:

Vogelherd | 31,900–23,060 years ago |

Hohlenstein-Stadel | 31,750 years ago |

Geissenklösterle | 35,000–32,000 years ago |

Stratzing | 31,790–28,400 years ago |

Until the 1994 discovery of the Chauvet Cave (approximately 33,000 years ago), these were the oldest dated pieces of Upper Palaeolithic art (Fig. 45). Most of the pieces are about only 5 cm (2 in) long, though an especially striking therianthropic figure with a lion’s head from Hohlenstein-Stadel is just over 29 cm (111⁄2 in) high (Fig. 46). Nearly all the pieces were carved from mammoth ivory, the only exception being made from mammoth bone. The ivory came from the centre of mammoth tusks; the harder outer ivory was used for projectile points. The pieces were carved with stone tools, but subsequent polishing removed most traces of the carving process. Joachim Hahn, the German archaeologist who has studied the pieces in detail, believes that the polishing was done with hide or wet limestone. His experiments suggest that it must have taken about 40 hours to make the Vogelherd horse, the most widely illustrated piece (Fig. 45, top).28

At Vogelherd, the statuettes were found in two strata (there were as many as ten occupation floors), but in only two locations, one above the other, an observation that suggests considerable continuity of site use. In addition to the statuettes, the sites yielded pierced ivory bâtons de commandement (decorated long bones with a hole at one end that have been interpreted as symbols of political power), perforated fox canines and ivory pendants, as well as stone endscrapers and burins, but the various kinds of items were not mixed indiscriminately. At Vogelherd, the statuettes were well away from a stone flaking area outside the cave and from an activity area within the rock shelter; at Stadel, the statuettes were far inside the shelter; at Geissenklösterle, they were on the fringe of two artefact concentrations.29 Although some of them were clearly used as pendants, this sort of spatial separation suggests that they were not part of daily, mundane activities. Hahn concludes that the rock shelters were used as caches, or storage sites, in an inhospitable landscape. He may well be right, and it is hard not to recall the caches of North American shamans. The Aurignacian sites, or areas within them, may also have been special places, entrances to a spiritual realm.

The species represented by the statuettes include

4 felines,

4 mammoths,

3 anthropomorphs,

2 bison,

1 bear, and

1 horse.30

The faunal remains found in the same rock shelters as the statuettes come from a much wider range of species – 21 in all; the image-makers focused on a limited bestiary.31 Although the small number of pieces makes generalizations hazardous, Hahn concluded: ‘As in wall art, animal species represented in mobiliary art do not simply mimic the relative proportions of animal species in the faunal assemblages from the sites.’ 32 Other criteria than simply food were operating in the selection of species for statuettes. By the Magdalenian, portable art embraced a wider range of animal motifs than parietal art.

Significantly, the set of species selected is similar to that found throughout Upper Palaeolithic parietal art. But, within the overall Upper Palaeolithic bestiary, the Aurignacian carvings place an unusually marked numerical emphasis on felines (though one must bear in mind that only a small number of pieces are known). This emphasis is particularly interesting in view of the comparatively large number of parietal images of felines found in Chauvet Cave, an Aurignacian site that was more or less contemporary with the southern German statuettes.33 Was there, at this time, a fairly general shamanistic concern with felines, and indeed other apparently dangerous animals, that was in some way modified over time? Judging from the presently available evidence that seems to have been the case.

Further, the hoofs or paws of the statuettes are hardly represented, a feature that recalls numerous parietal images. None of the Aurignacian sites in southern Germany has parietal art, but one of the portable art excavations (Geissenklösterle) yielded a piece of multicoloured, painted limestone.34 At this site, the statuettes came from the upper Aurignacian strata and the painted stone from the lower.

The evidence is too slight to make confident generalizations. Nevertheless, we need to ask: how can we account for the appearance of both two- and three-dimensional art at the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic? There is no evidence that one evolved out of the other. Are two distinct scenarios required to explain the two types of art, or can they both be explained by a single set of generating factors?

In answer to this question, I argue that the same neurological mechanism that explains the genesis of two-dimensional imagery also explains the origin of three-dimensional statuettes. How could this have been? The mental imagery that the nervous system projects in altered states of consciousness is not exclusively seen on two-dimensional surfaces. On the contrary, people in deep altered states of consciousness also see small, three-dimensional hallucinations. If, as I have argued, the world of (some) people in Upper Palaeolithic communities was invested with images even before they started ‘fixing’ them on cave walls, those images would have been three- as well as two-dimensional.

Next we must recall that the repertoire of animal motifs must have been established, in broad terms, before people started making parietal images. An established, restricted repertoire must also have been present before Aurignacians in southern Germany started making statuettes. Even as an explanation for the origin of two-dimensional imagery had to be consonant with a pre-existing repertoire of animal motifs, so, too, does an explanation for the earliest three-dimensional images. Moreover, apart from internal numerical emphases, those repertoires were similar in broad terms. This means that early Upper Palaeolithic people believed a set of animal species to have certain properties or meanings that made them special. The diverse evidence that I discussed in previous chapters strongly suggests that those properties and meanings included the supernatural potency that animal helpers gave to shamans and, further, that could be harnessed to accomplish various tasks, and the zoomorphic persona that shamans assumed when they went on outof-body travel to the subterranean or upper spirit worlds or to other parts of the landscape. From these premises, we may assume that fragments of those animals, such as ivory, teeth and antlers, were believed to possess related essences and powers, an assumption that has abundant ethnographic support (Chapter 9).

Now let us return to one of the aspects of parietal image-making that I noted earlier. The images were not so much painted onto rock walls as released from, or coaxed through, the living membrane (rather than ‘veil’ if we think of the bowels of the earth) that existed between the image-maker and the spirit world. In some instances, natural features of the rock stood for parts of the animals. I argue that this fundamental principle probably also applied to the making of three-dimensional images: the carver of the image merely released what was already inside the material. This is, of course, a well-known principle that sculptors in various cultures, including the Western tradition, speak about. Aurignacian three-dimensional image-makers, from their point of view, may therefore not have superimposed meaning (an image) on the otherwise meaningless pieces of ivory that they were handling; rather, they released the animal essence from within the fragments of animals. As we shall see in Chapter 9, many shamanistic communities believe in the regeneration of animals from bones. It need not follow that only lions could be carved from lion bones or only horses from horse bones; hunter-gatherer bestiaries, or symbologies, are more fluid than that. As we have seen, mammoth ivory was the favoured raw material for the statuettes.

The way in which these beliefs about animal power and fragments of animals could have come together with small, three-dimensional hallucinations of animals is clear. Under certain social circumstances, which may have varied from time to time and place to place, certain people (shamans) saw a relationship between the small, three-dimensional, projected mental images that they experienced at the far end of the intensified spectrum and fragments of animals that lay around their hearths. Remember that the set of significant species was already established, shared, spoken about, seen in visions and dreamed about. Subsequent cutting, scraping and polishing released the symbolic animals from within the pieces of ivory so that they became three-dimensional, materialized visions. The portable animal statuettes were therefore far more than decorative trinkets: they were reified three-dimensional spirit animals with all their prophylactic and other powers.

We have now moved some distance from the underworld of the caves and are in the open rock shelters that the Aurignacians occupied daily. It is therefore not surprising that, in later periods of the Upper Palaeolithic, when portable art became more various than present evidence suggests it was during the Aurignacian, a wider range of species came to be represented than the more limited set of motifs that we find in the specific, fixed contexts of cave walls. Portable art came to be made in more varied circumstances and contexts than the restricted circumstances established by the underground locations of parietal images. As with the three streams of image-making that flowed from initial fixed-vision parietal images, so with portable art a wide range of animal symbolism came to be associated with tool embellishments and socially significant body adornment of various kinds.

In all cultures, selected animals acquire spectra or sets of associations and meanings, not a single one-to-one meaning. It may well be that a carved three-dimensional pendant of a horse did not encode exactly the same segment of that species’ range of meaning as did a painting of a horse in a deep cavern.The context of an image focuses attention on one segment of its spectrum of associations. But the ‘subterranean’ focus of meaning would have been present in the background as a penumbra that imparted extra power to the pendant.35 We saw in the San case study that shamans were involved in hunting: they were believed to guide antelope into the waiting hunters’ ambush. This is not what is generally understood by ‘hunting magic’, but it goes some way towards explaining why, say, horses were engraved on spear-throwers. Spirit horses may well have been some shamans’ animal helpers; that is why they appear fixed on the subterranean membrane. At the same time, associating a horse image with a spear-thrower may have highlighted more general associations of success and power in hunting. Similarly, the meaningful spectra of some species did not extend from portable art to the nether world: they are therefore not depicted in cave art.

A comparable fluidity is evident in the geographical distribution of Aurignacian art: it seems not to have been a universal component of the Aurignacian technocomplex. There were centres of Aurignacian art in central France, the Pyrenees, and farther east in the Middle and Upper Danube Basin. Elsewhere there are many Aurignacian sites with comparable preservation, but no art.36 Again we note that the making of representational images was not an inevitable part of the Transition. Certain social circumstances were required for imagemaking.

A step towards understanding those circumstances is facilitated by a closer examination of the Aurignacian statuettes (Fig. 45). Hahn37 found that the horse from Vogelherd is in the posture that a stallion adopts to impress its females. The bear from Geissenklösterle is in an aggressive upright position. The two Vogelherd lions, with their triangular, backward-pointing ears are in the ‘tense open-mouth’ posture of a lion defending its kill. Both the Stadel lioness head and the one from Vogelherd also seem to be in an alert state.38 This ethological evidential strand leads Hahn to argue that the statuettes encoded notions of power and strength.39 But what sort of power and strength?

45 Some of the Aurignacian statuettes recovered at Vogelherd. The small horse has a chevron carved into its smooth surface; other statuettes are marked by curves, crosses and dots.

Thomas Dowson and Martin Porr answer this question in their own examination of the postures of the animals represented.40 They conclude that the statuettes were associated with an early form of shamanism: ‘entering an altered state of consciousness is often considered a dangerous activity’ and ‘shamans have to be strong and powerful to…perform the work they do’. To support this interpretation, Dowson and Porr point to the therianthropic statuette from Hohlenstein-Stadel, with its human body and feline head (Fig. 46). As they rightly say, transformation into an animal is an integral part of shamanism. In providing social and conceptual contexts for the statuettes, they note the comparatively segregated locations in which the objects were found and suggest that Aurignacian shamans may have performed their tasks in relative seclusion, though the statuettes’ use as pendants also suggests that they had a public significance.

Given the set of beliefs that I have now outlined, it is not difficult to see that the origin of three-dimensional images was not markedly different from that of two-dimensional images; the same generating principles applied to both. The earliest Upper Palaeolithic image-making was all underpinned by the same conceptual foundations.

A new threshold

The title of this chapter was circumspectly chosen. I have been concerned with one origin of image-making, that which took place during the west European Transition. The explanation that I have outlined for that particular instance does not preclude multiple independent origins elsewhere and at other times – once, that is, higher-order consciousness had evolved. Image-making did not originate in only one place and then diffuse throughout the world. The circumstances in other times and places may not have been identical to those that I have described for the west European Middle to Upper Palaeolithic Transition. They remain to be demonstrated, not merely asserted. There is nothing mechanistic about my explanation. But it nevertheless highlights certain universals in human neural morphology, shifting consciousness, and the ways in which people have no option but to rationalize and socialize the full spectrum. As we know from our own times, the ways in which people name and place value on segments of the spectrum is open to contestation. Indeed, it seems likely that within a given society the rationalizing of the spectrum will always be divisive and contested.

46 The Hohlenstein-Stadel therianthrope. It is part human, part lion, and stands approximately 30 cm (12 in) high.

The picture of the Transition that we have begun to build up has resolved a number of long-standing and seemingly intractable problems. We can now understand much better the kind of relationship that must have obtained between Neanderthals and the in-coming Homo sapiens communities. We can glimpse a kind of relationship that is different from anything we can possibly experience in the world today. We can also begin to comprehend why Neanderthals managed some activities but not others.

Importantly, we can begin to see social stirrings in the Homo sapiens camps, stirrings that were related to the socializing of the autistic end of the spectrum of higher-order consciousness and to image-making. Humanity was on the threshold of new kinds of social discrimination. In subsequent chapters we explore more carefully the kind of society that may have been evolving at this time and the roles that images and caves began to play.