One major factor in the development of photography around the world was the desire to record wars. Even today most people’s understanding of the nature of war comes from photographic images rather than literary accounts. It was, however, the highly critical reports of the London Times reporter William Russell on the progress of the Crimean War that led to Roger Fenton being sent to take photographs that would reassure the public. Fenton used the newly invented wet collodion process to produce more than 350 photographs which did, indeed, show scenes of calm and disciplined order. He produced a number of handsome albums with original photographs ‘tipped in’, but his images were also used as the basis of illustrations in the Illustrated London News. Illustrated newspapers produced hundreds of woodcuts, often laid out to create a narrative of events. It seems that an added sense of realism was given to the piece if it was ‘based on photographs’ rather than being the work of an artist or illustrator, even though the engraver would omit or add material in order to make a visual point or a more pleasing aesthetic effect.

collodion This process, known as wet collodion (or Ambrotype), invented by English photographer Frederick Scott Archer in 1851, increased the speed of photography as the glass plate was treated and exposed while still ‘wet’ (i.e. gummy) but it had the drawback of involving bulky equipment. It became one of the major processes until the invention in the 1870s of gelatin-coated plates known as dry plates.

Fenton spent only a short time in the Crimea and his work did little to reveal the hardships or horrors of war. The American Civil War (1861–5) was the first to be photographed extensively throughout its duration, and in which photography was seen not only as providing realistic images of the struggle, but also as ‘news’. In this sense, it also provided one of the foundation stones for the development of photojournalism. Michael L. Carlebach comments that:

Two weekly newspapers that were established in America in the years just preceding the Civil War made photographs and other visual materials equal partners of the printed word in the reporting of news. These new publications would provide the public, or at least the northern public, with accurate and timely illustrations of the war. The pictures they published, many based on photographs, offered vivid, graphic and reliable glimpses into all aspects of the conflict. For the first time, Americans would see through the eyes of a score of photographers, exactly what was going on at the front.

(Carlebach 1992: 63)

But, as Carlebach makes plain, these significant images were not the most numerous of the photographs produced in the war. A boom was experienced by photographic studios trying to deal with the demand for portraits of those who were going into battle. In addition, photographs of the commanders of the Federal army were turned out by the hundred; purchased by people anxious to support the cause and made the subject of a special tax.

The most important photographer of the Civil War was Matthew Brady. Already celebrated for his portraits, ‘Brady of Broadway’ produced photo graphs that showed scenes of action, together with shots of the dead on the battlefield, and more tranquil views of soldiers relaxing at their camps. Brady put teams of photographers into the field of battle, including Alexander Gardner, Timothy O’Sullivan and George Barnard, and published this work under his own imprint. Alan Trachtenberg describes his function in the following terms:

‘Brady’s pictures’ did not mean pictures made by Brady himself but those he displayed or published…. Organiser of one of several corps of private photographers, collector of images made by others, a kind of archivist or curator of the entire photographic campaign of the war, Brady played many roles, swarmed with ambiguities, in the war.

(Trachtenberg 1989: 72)

Since Brady’s time, no war or violent conflict has lacked its photographic record and interpreters. For example, hundreds of thousands of images of the First World War were made, most of which have been rendered anonymous by the system of classification and archiving that was subsequently employed. Despite the sheer number of photographs of that conflict, there is little work that really gives us a sense of the nature of trench warfare, and the poetry, films and paintings of the time are often more moving and revealing.

Photography was considerably more important as a means of depicting the Spanish Civil War (1936–9). The many illustrated journals of the day carried photographs and these images were influential in shaping people’s view of the war. The single most famous photograph was Robert Capa’s Death of a Loyalist Soldier which later became the subject of speculation as to its authenticity. Capa was also one of the photographers of the Second World War whose work became very familiar to the public, along with that of Bert Hardy, W. Eugene Smith, Carl Mydans and Life photographer David Douglas Duncan, who went on to produce heroic images of American soldiers in Korea and Vietnam. After the Spanish Civil War, Capa was one of the founders of the photo agency Magnum, which has enrolled many distinguished photographers over the years.1 Many histories of documentary and photojournalism in the last half century are written essentially around the work of members of the agency. Photo agencies are vital to the work of independent photographers and the archives they establish and support are a most important resource.

The Second World War (1939–45) blurred the distinction between combatant and civilian and, thereafter, war photographers concentrated as much attention on those caught up in conflict as on the soldiers themselves. This is, of course, also true for violent conflict which is not defined as a ‘war’, as in Cyprus or Northern Ireland.

Jorge Lewinski has commented that:

It is only in the post-war period, starting with the Korean war, that the immediacy of war photographs begins to have a significant effect. Since then, a stream of authentic images has overwhelmed us with cumulative power. The images from Korea, Cyprus, Israel, the Congo, Biafra and Vietnam have left their indelible mark on our imaginations.

(Lewinski 1978: 12)

Certainly, it is often said that the stream of images revealing the death, injury and sorrows of the people of Vietnam was a major factor in the public’s eventual repugnance for that war. In the sophisticated photographic work of the time the themes of martial conflict and civilian anguish are inter-twined. An excellent example is given in the work of Philip Jones Griffiths, who produced one of the most important photographic records of the war (Griffiths 1971).

War has been seen as an important subject for photography for a number of reasons: the photographer might reveal scenes and actions which would not otherwise come to the attention of the public; war inevitably throws up scenes of great emotional force which can best be captured by the camera; it has a dark psychic fascination for us, which coexists with our feelings of revulsion. The person who has most mused on this ambivalence is the English photographer Don McCullin, who has documented many wars and violent uprisings since the early 1960s (McCullin 2003).

We might ask why we particularly remember some photographs of war and what social function they might serve. It has been suggested that certain images are given iconic status within a society because they evoke and structure ideas about the culture of that place and are congruent with how its citizens feel about themselves.

Michael Griffin puts it succinctly:

The enduring images of war are not those that exhibit the most raw and genuine depictions of life and death on the battlefield, nor those that illustrate historically specific information about people, places and things, but rather those that most readily present themselves as symbols of cultural and national myth.

(Griffin 1999: 123)

On this reading, there are no unequivocally great photographs of war, only those that structure or re-enforce feelings already extant within a particular culture.

We should remember that war reporting, like other kinds of reportage, has depended historically on the ability of the photographer to bear witness to the action taking place. But, so powerful has been the influence of war reporting that military authorities make every effort to control journalists and photographers working in scenes of conflict. The unattached freelance reporter has all but disappeared and photographers increasingly find themselves forced to work at a distance from violent action. For some photojournalists, war reporting has, in consequence, taken on new forms that are more akin to meditations on the nature of war than direct reportage. For example, the French photographer Luc Delahaye (who is a member of Magnum and worked for Newsweek) became famous for his close-up pictures of war and scenes of violence. However, he abandoned this photojournalistic approach in favour of working with large-scale or panoramic cameras to produce big images that were designed to be shown in galleries. Instead of the vibrant confusion of struggle we are given a more distanced, considered and detached view of conflict.

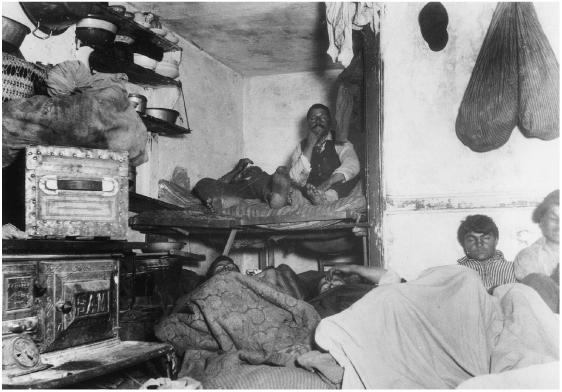

2.3 Paul Seawright, Room 1, 2003

This new kind of retrospective work, which has been called ‘aftermath photography’, may be seen in the pictures of a number of photographers, including those the Irish photographer Paul Seawright took in Afghanistan for the Imperial War Museum, London. These are large, colour works, that have no images of direct conflict, but show the traces of war, the scarred buildings and furrowed earth, together with the characteristic debris of battle. They have none of the busy activity of war photography, but are carefully composed works through which we can explore the nature of violent conflict.

Sarah James has described work in this kind in the following terms:

Surveying sites ruined by war and catastrophe – Bosnia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Kuwait, Beirut, Baghdad, Lebanon, Palestine, or Manhattan’s Ground Zero – photographers such as Simon Norfolk, Paul Seawright, Joel Meyerowitz and Sophie Ristelhueber have developed this strange new genre. Each works in saturated or subdued colour, often on a monumental scale and with thrilling precision … The surreal landscapes and alien environments charted by these photographers are as abstract, inhuman and incomprehensible as the wars that caused them.

(James 2013: 115)

Describing the work of Anne Ferran, Geoffrey Batchen points out that:

Refusing to tell us anything about what we are seeing, to give us the explanatory information we crave, these photographs challenge us to bring our own knowledge and desires to them. They might be said to represent the ground of history itself, waiting to be inscribed with meaning.

(Batchen et al. 2012: 228)

Susan Sontag (2003) Regarding the Pain of Others, London: Hamish Hamilton.

This strategy raises a number of questions: the old assertion based on authenticity (‘I saw it; I was there’) no longer holds good, but is replaced by a new implicit claim to respect the suffering of others by producing more structured and complex works that function as objects of critical contemplation. This moves the photographer out of the world of the media with its insatiable demand for immediate images and into the world of art. These pictures are no longer to be found in newspapers and magazines, but are to be seen on the walls of galleries. An apparent opposition is sometimes seen to exist between the world of concerned photography and the realm of art. Susan Sontag has argued that this is an exaggerated distinction:

Transforming is what art does, but photography that bears witness to the calamitous and the reprehensible is much criticised if it seems ‘aesthetic’; that is, too much like art.

(Sontag 2003: 68)

To escape the voyeuristic position of photojournalism, then, one may be accused of making elegant art objects out of the victims of disaster. But photojournalism is also under attack from quite different kinds of image-making. Commenting on the images of tortured Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib, Andy Grundberg laments the fact that the old disciplines of photojournalism have all but disappeared:

These photographs tell us that the codes of objectivity, professional ethics and journalistic accountability we have all relied on to ensure the accuracy of the news – at least in rough draft form – are now relics. In their place is a swirling mass of information, written as well as visual, journalistic as well as vernacular, competing to be taken as fact.

(Grundberg 2005: 108)

Andy Grundberg (2005) ‘Point and Shoot: How the Abu Ghraib Images Redefine Photography’, American Scholar, 74(1), Winter 2005: 108. Quoted in ERINA DUGANNE (2007) ‘Photography After the Fact’ in MARK REINHARDT, HOLLY EDWARDS and ERINA DUGANNE (eds) Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 73.

The Abu Ghraib photographs, then, were seen all over the world, and their shocking claim to authenticity resided in part in the fact that they were not presented as objective documents. Taken with cheap digital cameras and on mobile phones they were a species of personal photograph, of snapshots, made for the amusement of the photographers and their putative audience of colleagues and friends. Freed from any of the codes that govern the practice of photojournalism, they had a rawness and immediacy that contributed to their appalling power. We should observe, however, that carrying on the old task of ‘bearing witness’ while working outside the structures of professional photography has become quite common. Many of the photographs of the destruction of the Twin Towers in New York or the effects of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans were similarly made by amateurs using very simple devices. In both cases they were exhibited together with work by artists and photojournalists. This new promiscuous heaping together of work made for different reasons and from different professional standpoints makes it very difficult to be clear about the current state of photojournalism.

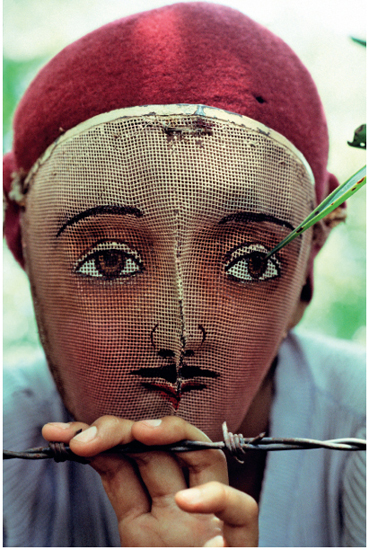

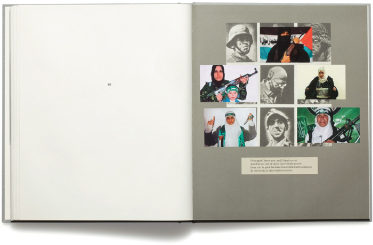

2.4 Abu Ghraib, 2004

D.L. Strauss (2003) Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography and Politics, New York: Aperture Books.

Certainly, in recent years the relationship between photographer and suffering subject has become increasingly the subject of debate. The argument that photography gives an aesthetic gloss to anguish is a very old one, but is far from being resolved. David Levi Strauss has argued that:

The idea that the more transformed or ‘aestheticized’ an image is, the less ‘authentic’ or politically valuable it becomes, is one that needs to be seriously questioned…. To represent is to aestheticize: that is, to transform. It presents a vast field of choices but it does not include the choice not to transform, not to change or alter whatever is being represented. It cannot be a pure process in practice. This goes for photography as well as for any other means of representation.

(Strauss 2003: 9)

Susie Linfield argues that photojournalists now find themselves in a Catch 22 situation:

Some are criticized for taking too-beautiful pictures, while others are chided for images that are too ugly to bear; some are criticized for a gruesome realism, while others are accused of being overly romantic in their approach.

(Linfield 2010: 44)

She argues that these dichotomies are inevitable when trying to ‘show the unshowable’ and suggests that:

These critics seek something that does not exist: an uncorrupted, unblemished photographic gaze that will result in images flawlessly poised between hope and despair, resistance and defeat, intimacy and distance.

(ibid.: 44)

Photographers and editors still have to make crucial choices about the technical means of production; the intended audience, the medium through which photographs are displayed and the relationship of any particular images to the vast number already in circulation.

Reviewing the prestigious World Press Photo awards, the artists Adam Broomberg and Olivier Chanarin described photojournalism as ‘a photographic genre in crisis’ and went on to list the dominant themes of the 81,000 photographs submitted for consideration:

Again and again similar images are repeated with only the actors and settings changing. Grieving mothers, charred human remains, sunsets, women giving birth, children playing with toy guns, cock fights, bull fights, … [etc]

(Broomberg and Chanarin 2008: 99)

In their own work Broomberg and Chanarin combine photographs and texts in order to unpick the nature of documentary photography. In 2013 they won the Deutsche Börse photography prize and were praised for their book War Primer 2, which uses internet screengrabs and photographs taken on mobile phones to rework Berolt Brecht’s War Primer of 1955. The piece is a sustained exploration of the role of photography in what the Americans called ‘the war on terror’.

2.5 Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, Plate 80 from War Primer 2, 2011

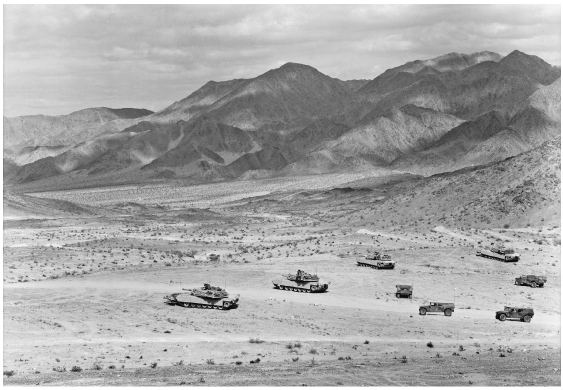

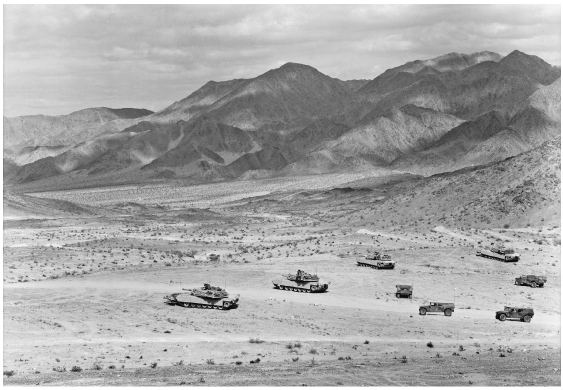

2.6 An-My Lê, 29 Palms: Mechanized Assault, 2003–4

Photojournalism and documentary are linked by the fact that they claim to have a special relationship to the real; that they give us an accurate and authentic view of the world. This claim has often been challenged on a number of grounds. Perhaps the simplest and most obvious test of authenticity is to ask whether what is in front of the lens to be photographed has been tampered with, set up, or altered by the photographer.

Early in its history photography had been presented with many cases of fraud, as, for example, when the French photographer E. Appert published his book Les Crimes de la Commune in 1871. This purported to be a record of the vile behaviour of those who took part in the rising of the Paris Commune and was received with relish by many bourgeois commentators of the time. It consists, for the most part, of crudely montaged and retouched photographs, but was convincing enough for a public who were confident that the camera could not lie. It would, however, be incorrect to deduce that in the nineteenth century only outright deception was commented upon. Many sophisticated arguments about the ability of photographs to be true to appearances were rehearsed at that time. Indeed the Victorians were to stage a dramatic debate on the relationship between truth and representation in the public trial of Dr Barnardo.

In 1876 the philanthropist Dr T. J. Barnardo appeared at a hearing, having been charged with deceiving the public. His detractors claimed, and Barnardo finally conceded, that he had misled the public in his use of ‘before and after’ photographs of the orphans in his care. He had produced a series of cards which purported to reveal the transformative power of his project: one card was of dirty, ragged children lounging about against a background of urban decay; a second card showed one of these children cleaned up and neatly dressed, undertaking some useful task. Dr Barnardo used child models for these cards and one, Katie Smith, is pictured in several of them, posing as a crossing-sweeper or a match-seller. At the hearing Barnardo agreed that Katie had never sold matches, but he pointed out that she was a child of the streets who might well have ended up as a beggar and that, in any case, she represented the appearance and state of a match-girl in an honest manner. Moreover, Katie could easily have stumbled into that kind of life had she not been saved by his mission.

As a result of the public hearing Barnardo gave up using photographs in this way, but his case raises questions that were to recur throughout the next century. Why should we trust the camera to be true to appearances? What is the relationship between the accurate portrayal of a single case and a general truth about the nature of things? Cannot something arranged or set up offer us an authentic insight into reality? It was questions of this kind that were rehearsed, long after Barnardo, in the furore that broke out over a photograph made in the USA.

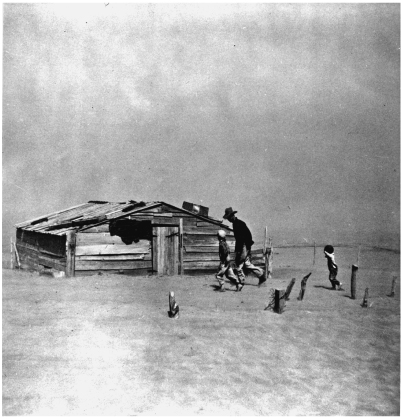

In 1936 the American photographer Arthur Rothstein photographed a steer’s skull that had been bleached by the sun and left lying on the earth. This was a simple still life, then, but one that was clearly intended to exemplify the contemporary crisis in agriculture. Rothstein took two photographs of this object, the most famous of which shows it lying on cracked, baked, waterless earth. The second, however, revealed it as resting on the less symbolically charged ground of a stretch of grass. The photographer acknowledged that he had moved the skull a few metres in order to obtain a more dramatic pictorial effect. When the presence of these two rather different images was discovered there was an outcry from Republican politicians, who claimed that the public had a right to see photographs that were objectively true rather than those that had been manipulated in order to make a rhetorical point. Two kinds of truth were in play; for, while the right-wing politicians demanded a truth at the denotative level, the photographer, like Dr Barnardo, laid claim to a greater truth at the connotative level. Nevertheless, Rothstein was at pains to draw attention to the smallness of his intervention in the ‘real’ state of things and would certainly have subscribed to the view that the authentic could only be guaranteed by a relatively unmediated representation of things as they are.

So, the practice of documentary was and is problematic and, over time, a number of conventions and practices evolved to mark ‘authentic documentary’ from other kinds of work. These included, for example, printing the whole of the image with a black border around it to demonstrate that everything the camera recorded was shown to the viewer. At another time, scenes lit by flash were deemed illegitimate, as only the natural light that fell on the scene should be used. A kind of rudimentary technical ethic of documentary work emerged which ‘guaranteed’ the authenticity of the photograph. We may note that studio-based photography, whether for commercial purposes or as art, was made by suppressing what was contingent within the photographic frame. The scene was designed in such a way that all aspects of the image were controlled and carefully placed. We have already observed that any attempt to arrange and structure the location by a documentary photographer would be regarded as illegitimate behaviour, yet the aesthetic demand for well-composed shots remained.

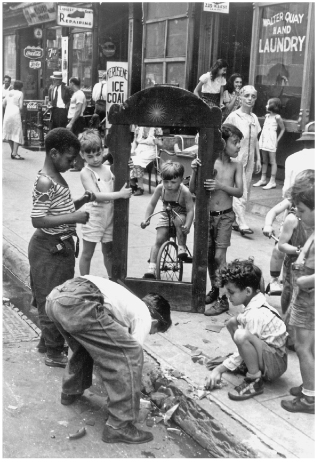

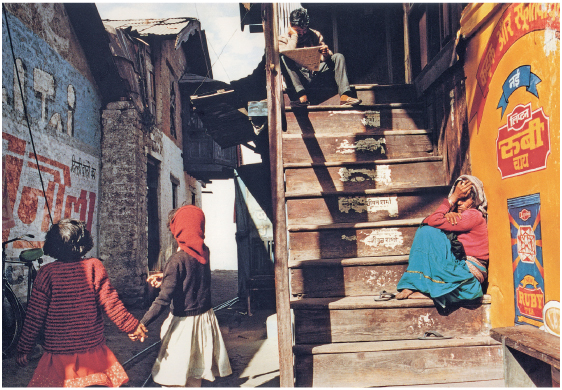

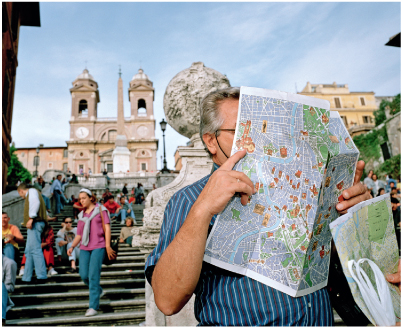

Documentary photographers, too, took considerable pains to control the nature of a scene without making any obvious change to it. Thus, the celebrated French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson lay in wait for all the messy contingency of the world to compose itself into an image that he judged to be both productive of visual information and aesthetically pleasing. This he called ‘the decisive moment’, a formal flash of time when all the right elements were in place before the scene fell back into its quotidian disorder. Increasingly, documentary turned away from attempting to record what would formerly have been seen as its major subjects. Instead, it began to concentrate on exploring cultural life and popular experience, and this often led to repre sentations that celebrated the transitory or the fragmentary. The endeavour to make great statements gave way to the recording of little, dislocated moments which merely insinuated that some greater meaning might be at stake (Cartier-Bresson 1952). Cartier-Bresson’s humanist work is often regarded as documentary or as photojournalism but he is also seen as working outside the constraints of labels of this kind. As photographer and theorist Allan Sekula has pointed out,

Documentary is thought to be art when it transcends its reference to the world, when the work can be regarded, first and foremost, as an act of self-expression on the part of the artist.

(Sekula 1978: 236)

Allan Sekula (1978) ‘Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)’ in J. Liebling (ed.) Photography: Current Perspectives, Rochester, NY: Light Impressions Co.

The problem, then, becomes how we define ‘reference to the world’ and how documentary photographers can demonstrate their fidelity to the social world. To have to engage with particular conventions, technical processes and rhetorical forms in order to authenticate documentary undermines the notion of the objective camera and with it, one might imagine, any claim of documentary to be any more truthful to appearances than other forms of representation.

We are now so used to the dominance of digital media in photography that we scarcely need reminding that the convergence between computing and audio-visual technologies has produced new technologies which have transformed the means of image-making together with its social, commercial and aesthetic practices. Digital media are marked by more than simply radical changes in photographic technologies. Their ability to create, manipulate and edit images has given new prominence to arguments about the nature of photography and taken them into the popular domain. These may briefly be summarised as questions about the nature of the photographic image and about new ways of defining and understanding ‘the real’. At first digital technologies simply copied those of traditional photography and there is still a sense in which a world of pixels and bytes has simply replaced that of chemicals and paper. However, all profound changes in technology begin by aping the past before going on to offer novel ways of using a medium. Fred Ritchin notes that:

Digital media … will not merely simulate an older style of photography, but strategies will emerge that are more capable of depicting an evolving universe. Rather than attempting simply to imitate previous media while offering an increase in efficiency, digital media, including their visual aspects, will eventually involve a more flexible, integrative, ‘hyperphotography’ that takes advantage of the many potentials of digital platforms, including links, layers, hybridization, asynchronicity, nonlinearity, nonlocality, malleability, and the multivocal. The results may at first resemble gimmickry, but eventually they will be transformative.

(Ritchin 2013: 57)

It is commonplace now to note that images with all the appearance of ‘real’ photographs may have been created from scratch on a computer, montaged from many sources, altered in some respects, or radically transformed. Figures may be added or removed and the main constituents of the picture rearranged to suggest new relationships or bizarre conjunctions. Does all this not destroy the claim of photography to have a special ability to show things as they are and raise serious doubts about those genres with a particular investment in the ‘real’ – documentary and photojournalism?

We can, of course, observe that, as we have already seen, the manipulation of images is nothing new and that photographs have been changed, touched-up or distorted since the earliest days. But we are not looking here merely at a technically sophisticated way of altering images, but at much more profound changes that challenge the ontological status of the photograph itself. If a photograph is not of something already existing in the world, how can we regard it as an accurate record of how things are? Roland Barthes’ influential conception of the nature of the photograph is that it is the result of an event in the world, evidence of the passing of a moment of time that once was and is no more, which left a kind of trace of the event on the photograph. It is this trace which has been considered to give photographs their special relationship to the real. That is that they function, in the typology of signs offered by the American semiotician C.S. Peirce, as indexical signs.

The nature of the sign within semiological systems is important, but it is interesting to note that we have always known that photographs are malleable, contrived and slippery, but have, simultaneously, been prepared to believe them to be evidential and more ‘real’ than other kinds of images. It is possible to argue that the authenticity of the photograph was validated less by the nature of the image itself than through the structure of discursive, social and professional practices which constituted photography. Any radical transformation in this structure makes us uneasy about the status of the photograph. Not only do we know that individual photographs could have been manipulated, but our reception and understanding of the world of signs may have been transformed.

Writing in the French newspaper Liberation in 1991, the social theorist, Jean Baudrillard famously remarked that ‘the Gulf war did not take place’ (Baudrillard 1995). He was commenting on the nature of the real and the authentic in our time and suggesting that in the world of the spectacle, it is pointless to posit an external reality that is then pictured, described and represented. In his view everything is constructed and our sense of the world is mediated by complex technologies that are themselves a major constituent of our reality. What took place, then, was not the first Gulf War but a whole sequence of political, social and military actions that were acted out in a new kind of social and technical space. While this may be an extreme way of formulating the argument, it is clear that a complex of technical, political, social and cultural changes has transformed not just photography, but the whole of visual culture. For example, David Campany points out that ‘almost a third of all news “photographs” are frame grabs from video or digital sources’ and comments that:

The definition of a medium, particularly photography, is not autonomous or self-governing, but heteronymous, dependent on other media. It derives less from what it is technologically than what it is culturally. Photography is what we do with it. And what we do with it depends on what we do with other image technologies.

(Campany 2003: 130; emphasis in original)

One significant consequence of this has been a new merging and lack of definition between photographic genres. It is increasingly difficult to distinguish one kind of photographic practice from another. As we shall see later, titles such as ‘documentary’ are of little use as labels for the new kind of work that is being produced. Indeed, all descriptive titles have been freely appropriated and find themselves used in curious couplings, for example one sub-genre of photography now well established in the USA is that of ‘wedding photojournalism’.

In more recent years there has been a huge increase in the number of news story photographs taken by amateurs. A new figure has come onto the stage: that of the citizen photographer. These are people who may have no particular training in photography, who are answerable to no editor, and do not necessarily subscribe to any journalistic ethic. Sometimes these are individuals who happen to record some exciting event on a single occasion, but a growing number are people who set out in a systematic way to record the scenes around them using a mobile phone or small digital camera. Where they are caught up in dramatic events their work may be seen around the world and may help shape the dominant perceptions of these events. Elsewhere, the pictures may simply be shared with family and friends.

For decades documentary and photojournalism depended on a system that had a clear separation, but interdependence, between its various parts. Between photographers and the subjects of photographs, between the publishers of these photographs (with a staff of people who influenced the nature of the final image – editors, picture editors, layout artists, printers) and the consumers of the photographs – the readers of the newspapers or illustrated magazines in which they appeared. Editors could commission photographs or draw on specialist agencies or picture libraries for them. It is this system that has gradually disappeared. The illustrated magazines gave way to the influence of television and newspaper colour supplements. These were, at first, a rich site for serious photojournalism, but were primarily vehicles for advertising and came to specialize in fashion, lifestyle and celebrity stories. This system is now largely a thing of the past. The citizen journalist can upload images to a number of sites without intervention from editors or other gatekeepers and the consumers of these pictures are usually also producers. Not only are social networks acting as publishers of photographs and news stories, but, increasingly, the mainstream media are accessing and referencing them to follow events as they unfold.

Newspaper and magazine editors, then, can commission work of this kind or draw on online sites as a source of images. The presence of citizen photographers is changing the nature of reportage, a process that is also driven by the economic imperatives of modern journalism. Noting that the profession of photojournalism has been in decline since the fall of the illustrated magazines, Julian Stallabrass comments that:

Economically pressed news organisations often prefer to provide c ameras (but little training) to willing locals rather than fly out professionals to a scene of conflict. Rates paid for the publication of newspaper photographs have been in steep decline. Foreign news – and indeed all hard news – has been squeezed for resources and space by cheaper and more advertising-friendly features on lifestyle, products and celebrity.

(Stallabrass 2013: 44)

Steven Hoelscher (ed.) (2013) Reading Magnum: A Visual Archive of the Modern World, Austin: University of Texas Press.

If we add to these economic forces the fact that some governments and participants make it increasingly difficult for photographers to work in scenes of conflict, the rise of the on-the-spot amateur would seem to be irresistible. They might be seen to be carrying on the old task of ‘bearing witness’ while working outside the structures of professional photography. Indeed, it is possible that the pictures of conflict returned from a simple camera or a mobile phone may imprint the notion of the authentic more securely than the sophisticated images presented by a professional photographer.

Of course, professional and highly developed photo agencies are still a source of images for editors. Even here, though, the world is changing. Many major agencies are now storing only digital images. Magnum, for example, has given up sending paper-based photographs to those who wish to use them. Digitized and stored online, it is now quick and easy to download images, but some people regret the passing of material objects and the ability to handle an actual print. The Magnum archive has passed to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas where it will be available to scholars who want to explore the nature of photography in the twentieth century.