Thinking about photography

Debates, historically and now

In his Preface to Photography, A Very Short Introduction, historian Steve Edwards asks us to imagine a world without photography (Edwards 2006). His point, of course, is that it is almost impossible for us to do so; photography permeates all aspects of our life, acting as a principal source and repository of information about our world of experience. It follows that historical, theoretical and philosophical explorations of photographs as images and objects, and of photography as a range of types of practice operating in varying contexts, are necessarily wide-ranging. There is no single history of photography.

As E.H. Carr has observed, history is a construct consequent upon the questions asked by the historian (Carr 1964). Thus, he suggests, histories tell us as much about the historian as about the period or subject under interrogation. Stories told reflect what the historian hopes to find, and where information is sought. He was writing in an era when libraries and archives were the primary research locations. Nowadays we may start by researching online. But his note of caution remains relevant: fact gathering may be influenced by many factors, not least the particular networks used by web-based search engines. It is up to us to evaluate the status of our sources and the significance of our findings.

Further more, the historian’s selection and organisation of material is to some extent predetermined by the purpose and intellectual parameters of any particular project. Such parameters reflect particular institutional constraints as well as the interests of the historian (for instance, academics may be expected to complete research within a set period of time). Projects are also framed by underpinning ideological and political assumptions and priorities.

Such observations are obviously pertinent when considering the history of photography. They are also relevant to investigating ways in which photography has been implicated in the construction of history. As the French cultural critic, Roland Barthes, has pointed out, the nineteenth century gave us both history and photography. He distinguishes between history which he describes as ‘memory fabricated according to positive formulas’, and the photograph defined as ‘but fugitive testimony’ (Barthes 1984: 93).

Attitudes to photography, its contexts, usages, and critiques of its nature are explored here through brief discussion of key writings on photography. The chapter is in four sections: Aesthetics and technologies, Contemporary debates, Histories of photography, and Photography and social history. The principal aim is to locate writings about photography both in terms of its own history, as a specific medium and set of practices, and in relation to broader historical, theoretical and political considerations. Thus we introduce and consider some of the different approaches – and difficulties – which emerge in relation to the project of theorising photography. The references are to relatively recent publications, and to current debates about photography; however, these books often refer back to earlier writings, so a history of changing ideas can be discerned. This history focuses on photography itself as well as considering photography alongside art history and theory, and cultural history and theory more generally.

As with any abbreviated history, this chapter can only offer brief summaries of some of the historical turning points and theoretical concerns that have informed and characterised debates about photography from its inception. Our aim is to identify some key questions and offer starting points for further research and discussion which are taken up in the following chapters and also through the references to further reading (in margins and notes). Photography is ubiquitous and it penetrates culture in very diverse ways. Nowadays, it plays a central role within social media on the one hand, while being a major factor within the art market on the other. These activities go on alongside longer standing fields of operation (including but not restricted to: documentary and photojournalism; people and places; personal, domestic and family photog raphy; travel, exploration and representation of cultures other than our own; commerce and advertising). The questions that we might ask, then, shift according to the type of practice being considered, but whatever the field of operation analysis of the role of photographic images is always pertinent to critical interrogations.

In the 1920s, when Moholy-Nagy commented on the future importance of camera literacy, he could hardly have anticipated the extent to which photographic imagery would come to permeate contemporary communication. Indeed, the late twentieth-century convergence of audio-visual technologies with computing led to a profound and ongoing transformation in the ways in which we record, interpret and interact with the world.

In recent years this has been marked both by the astonishing speed of innovation and by a rapid extension and incorporation of technologies within new social, cultural, political and economic domains. As Martin Lister remarked in 2009, we have ‘witnessed a number of convergences: between photography and computer-generated imaging (CGI), between photographic archives and electronic databases, and between the camera, the internet and personal mobile media, notably the mobile telephone’ (Lister in Wells 2009). Indeed, nowadays the mobile (cell) phone is also the camera.

We often see this ferment of activity as a defining feature of the twenty-first century and, perhaps, think of it as a unique moment in human history. But, in the 1850s, many people also thought of themselves as living in the forefront of a technological revolution. From this historical distance, it is hard to recapture the extraordinary excitement that was generated in the middle of the nineteenth century by a cluster of emerging technologies. These included inventions in the electrical industries and discoveries in optics and in chemistry, which led to the development of the new means of communication that was to become so important to so many spheres of life – photography. Hailed as a great techno logical invention, photography immediately became the subject of debates concerning its aesthetic status and social uses.

The excitement generated by the announcement, or marketing, of innovations tends to distract us from the fact that technologies are researched and developed in human societies. New machinery is normally presented as the agent of social change, not as the outcome of a desire for such change, i.e. as a cause rather than a consequence of culture. However, it can be argued that particular cultures invest in and develop new machines and technologies in order to satisfy previously foreseen social needs. Photography is one such example. A number of theorists have identified precursors of photography in the late eighteenth century. For instance, an expanding middle-class demand for portraiture which outstripped available (painted) means led to the development of the mechanical physiognotrace1 and to the practice of silhouette cutting (Freund 1980). Geoffrey Batchen also points out that photography had been a ‘widespread social imperative’ long before Daguerre and Fox Talbot’s official announcements in 1839. He lists 24 names of people who had ‘felt the hitherto strange and unfamiliar desire to have images formed by light spontaneously fix themselves’ from as early as 1782 (Batchen 1990: 9). Since most of the necessary elements of technological knowledge were in place well before 1839, the significant question is not so much who invented photography but rather why it became an active field of research and discovery at that particular point in time (Punt 1995).

Once a technology exists, it may become adapted and introduced into social use in a variety of both foreseen and unforeseen ways. As cultural theorist Raymond Williams has argued, there is nothing in a technology itself which determines its cultural location or usage (Williams 1974). If technology is viewed as determining cultural uses, much remains to be explained. Not the least of this is the extent to which people subvert technologies or invent new uses which had never originally been intended or envisaged. In addition, new technologies become incorporated within established relations of production and consumption, contributing to articulating – but not causing – shifts and changes in such relations and patterns of behaviour.

Charles Baudelaire

(1821–1867) Paris-based poet and critic whose writings on French art and literature embraced modernity; he stressed the fluidity of modern life, especially in the metropolitan city, and extolled painting for its ability to express – through style as well as subject-matter – the constant change central to the experience of modernity. In keeping with attitudes of the era, he dismissed photography as technical transcription, perhaps oddly so given that photography was a product of the era which so fascinated him.

Central to the nineteenth-century debate about the nature of photography as a new technology was the question as to how far it could be considered to be art. Given the contemporary ubiquity of photography, including the extent to which artists use photographic media, to posit art and technology as binary opposites now seems quite odd. But in its early years photography was celebrated for its putative ability to produce accurate images of what was in front of its lens; images that were seen as being mechanically produced and thus free from the selective discriminations of the human eye and hand. On precisely the same grounds, the medium was often regarded as falling outside the realm of art, as its assumed power of accurate, dispassionate recording appeared to displace the artist’s compositional creativity. Debates concerning the status of photography as art took place in periodicals throughout the nineteenth century. The French journal La Lumière published writings on photography both as a science and as an art.2 Baudelaire linked ‘the invasion of photography and the great industrial madness of today’ and asserted that ‘if photography is allowed to deputize for art in some of art’s activities, it will not be long before it has supplanted or corrupted art altogether’ (Baudelaire 1859: 297). In his view photography’s only function was to support intellectual enquiry:

Photography must, therefore, return to its true duty which is that of handmaid of the arts and sciences, but their very humble handmaid, like printing and shorthand, which have neither created nor supplemented literature. Let photography quickly enrich the traveller’s album and restore to his eyes the precision his memory may lack; let it adorn the library of the naturalist, magnify microscopic insects, even strengthen, with a few facts, the hypotheses of the astronomer; let it, in short, be the secretary and record-keeper of whomsoever needs absolute material accuracy for professional reasons.

(Baudelaire 1859: 297)

‘Absolute material accuracy’ was seen as the hallmark of photography because most people at the time accepted the idea that the medium rendered a complete and faithful image of its subjects. Moreover, the nineteenth-century desire to explore, record and catalogue human experience, both at home and abroad, encouraged people to emphasise photography as a method of naturalistic documentation. Baudelaire, who was among the more prominent French critics of the time, not only accepts its veracity but adds: ‘if once it be allowed to impinge on the sphere of the intangible and the imaginary, on anything that has value solely because man adds something to it from his soul, then woe betide us!’ (1859: 297). Here he is opposing industry (seen as mechanical, soulless and repetitive) with art, which he considered to be the most important sphere of existential life. Thus Baudelaire is evoking the irrational, the spiritual and the imaginary as an antidote to the positivist interest in measurement and statistical accuracy which, as we have noted, characterised much nineteenth-century investigation. From this point of view, for many nineteenth century critics in Western culture, steeped as they were in empiricist methods of enquiry, the mechanical nature of the camera militated against its use for anything other than mundane purposes.

Nineteenth-century photographers responded to such critical debates in two main ways: either they accepted that photography was something different from art and sought to discover what the intrinsic properties of the medium were; or they pointed out that photography was more than a mechanical form of image-making, that it could be worked on and contrived so as to produce pictures which in some ways resembled paintings. ‘Pictorial’ photography, from the 1850s onwards, sought to overcome the problems of photography by careful arrangement of all the elements of the composition and by reducing the signifiers of technological production within the photograph. For example, they ensured that the image was out of focus, slightly blurred and fuzzy; they made pictures of allegorical subjects, including religious scenes; and those who worked with the gum bichromate process scratched and marked their prints in an effort to imitate something of the appearance of a canvas.

In the other camp were those photographers who celebrated the qualities of straight photography and did not want to treat the medium as a kind of monochrome painting. They were interested in photography’s ability to provide apparently accurate records of the visual world and tried to give their images the formal status and finish of paintings while concentrating their attention on its intrinsic qualities.

See ch. 6 for discussion of Pictorialism as a specific photographic movement.

straight photography

Emphasis upon direct documentary typical of the Modern period in American photography.

Most of these photographs were displayed on gallery walls – this was a world of exhibition salons, juries, competitions and medals. In the journals of the time (which already included the British Journal of Photography), tips about technique coexisted with articles on the rules of composition. If the photographs aspired to be art, their makers aspired to be artists, and they emulated the characteristic institutions of the art world. However, away from the salon, in the high streets of most towns, jobbing photographers earned a living by making simple photographic portraits of people, many of whom could not have afforded any other record of their own appearance. This did not please the painters:

The cheap portrait painter, whose efforts were principally devoted to giving a strongly marked diagram of the face, in the shortest possible time and at the lowest possible price, has been to a great extent superseded. Even those who are better entitled to take the rank of artists have been greatly interfered with. The rapidity of execution, dispensing with the fatigue and trouble of rigorous sittings, together with the supposed certainty of accuracy in likeness in photography, incline many persons to try their luck in Daguerreotype, a Talbotype, Heliotype, or some method of sun or light-painting, instead of trusting to what is considered the greater uncertainty of artistic skill.

(Howard 1853: 154)

The industrial process, so despised by Baudelaire and other like-minded critics, is here seen as offering mechanical accuracy combined with a degree of quality control. Photography thus begins to emerge as the most commonly used and important means of communication for the industrial age.3

Writing at about the same time as Baudelaire, Lady Elizabeth Eastlake agreed that photography was not an art but emphasised this as its strength.4 She argued that:

She is made for the present age, in which the desire for art resides in a small minority, but the craving, or rather the necessity for cheap, prompt, and correct facts in the public at large. Photography is the purveyor of such knowledge to the world. She is the sworn witness of everything presented to her view … (her studies are ‘facts’) … facts which are neither the province of art nor of description, but of that new form of communication between man and man – neither letter, message, nor picture – which now happily fills the space between them.

(Eastlake 1857: 93)

In this account, photography is not so much concerned with the development of a new aesthetic as with the construction of new kinds of knowledge as the carrier of ‘facts’. These facts are connected to new forms of communication for which there is a demand among all social groups; they are neither arcane nor specialist, but belong in the sphere of everyday life. In this respect, Eastlake was one of the first writers to argue that photography is a democratic means of representation and that the new facts will be available to everyone. Photography does not merely transmit these facts, it creates them, but Eastlake characterised photography as the ‘sworn witness’ of the appearance of things. This juridical phrase strikingly captures what, for many years, was considered to be the inevitable function of photography – that it showed the world without contrivance or prejudice. For Eastlake, such facts came from the recording without selection of whatever was before the lens. It is photography’s inability to choose and select the objects within the frame that locates it in a factual world and prevents it from becoming art:

Every form which is traced by light is the impress of one great moment, or one hour, or one age in the great passage of time. Though the faces of our children may not be modelled and rounded with that truth and beauty which art attains, yet minor things – the very shoes of the one, the inseparable toy of the other – are given with a strength of identity which art does not even seek.

(Eastlake 1857: 94; emphasis in original)

The old hierarchies of art have broken down. Photography bears witness to the passage of time, but it cannot make statements as to the importance of things at any time, nor is it concerned with ‘truth and beauty’ or with teasing out what underlies appearances. Rather, it voraciously records anything in view; in other words the image captures information beyond that which concerned the photographer.

Photography, then, is concerned with facts that are ‘necessary’, but may also be contingent, drawing our attention to what formerly went un noticed or ignored. Writing within 15 years of its invention Eastlake points to the many social uses to which photography had already been put:

photography has become a household word and a household want; it is used alike by art and science, by love, business and justice; is found in the most sumptuous saloon and the dingiest attic – in the solitude of the Highland cottage, and in the glare of the London gin palace – in the pocket of the detective, in the cell of the convict, in the folio of the painter and architect, among the papers and patterns of the mill owner and manufacturer and on the cold breast of the battle field.

(Eastlake 1857: 81)

For Eastlake, photography is ubiquitous and classless; it is a popular means of communication. Of course, it was not true that people of all classes and conditions could commission photographs as a necessary ‘household want’ – she anticipates that state by several decades, during which time the use of photography was also spreading from its original practitioners (relatively affluent people who saw themselves as experimenters or hobbyists) to those who undertook it as a business and began to extend the repertoire of conventions of the ‘correct’ way to photograph people and scenes.

Eastlake’s facts are produced, she claims, by a new form of communication, which she is unable to define very clearly. But for all her vagueness, she does identify an important constituent in the making of modernity: the rise of previously unknown forms of communication which had a dislocating effect on traditional technologies and practices. She was writing at an historical moment marked by a cluster of technical inventions and changes and she places photography at the centre of them. The notion that the camera should aspire to the status of the printing press – a mechanical tool which exercises no effect upon the medium which it supports – is here seriously challenged. For Eastlake calmly accepts that photography is not art, but hints at the displacing effect the medium will have on the old structures of art; photography, she says, bears witness to the passage of time, but it cannot select or order the relative importance of things at any time. It does not tease out what underlies appearances, but records voraciously whatever is in its view. By the first decade of the twentieth century the Pictorialists had all but retreated from the field and it was the qualities of straight photography that were subsequently prized. Moreover, modernism argued for a photography that was in opposition to the traditional claims of art.

In Britain, as elsewhere, the idea of documentary has underpinned most photographic practices since the 1930s. The terminology is indicative: the Oxford English Dictionary definition of ‘documentary’ is ‘to document or record’.

In the days of chemical photography, and prior to the possibilities afforded by internet tools such as Google Earth, the simultaneous ‘it was there’ effect of photographs recording people and circumstances contributed to the authority of the photographic image and, arguably still does so. However, nowadays, in according authority to pictures, we are more likely to question the circumstances under which photographs have been made, their source, the status of the photographer and the purpose for which an image was made. For example, we might view pictures uploaded by local people documenting an incident or set of circumstances as more authentic than images authorised by a company or political organisation. Accepting that digital photography and digital imaging are now major industries contributing within print and online media, when assessing the significance of particular pictures we take into account image-making contexts and purposes. If documentary as a genre involves visual records for future reference, now we are very likely to ask from whose point of view such documents were made.

Walter Benjamin

(1892–1940) Born in Berlin, Benjamin studied philosophy and literature in a number of German universities. In the 1920s he met the playwright, Bertolt Brecht, who exercised a decisive influence on his work. Fleeing the Nazis in 1940, Benjamin found himself trapped in occupied France and committed suicide on the Spanish border. During the 1970s his work began to be translated into English and exercised a great critical influence. His critical essays on Brecht were published in English under the title Understanding Brecht in 1973. Benjamin was an influential figure in the exploration of the nature of modernity through essays such as his study of Baudelaire, published as Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism (London: Verso, 1973). He is acclaimed as one of the major thinkers of the twentieth century, particularly for his historically situated interrogations of modern culture. Two highly important essays for the student of photography are ‘A Short History of Photography’ (1931) and ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1936). The latter essay and ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ are frequently drawn upon in discussion of the cultural implications of new technological developments.

The simultaneous ‘it was there’ (the pro-photographic event) and ‘I was there’ (the photographer) effect of the photographic record of people and circumstances contributes to the authority of photographs. Photographic aesthetics commonly accord with the dominant modes and traditions of Western two-dimensional art, including perspective and the idea of a vanishing point. Indeed, as a number of critics have suggested, photography not only echoes post-Renaissance painterly conventions, but also achieves visual renderings of scenes and situations with what seems to be a higher degree of accuracy than was possible in painting. Photography can, in this respect, be seen as effectively substituting for the representational task previously accorded to painting. In addition, as Walter Benjamin argued in 1936, changes brought about by the introduction of mechanical means of reproduction which produced and circulated multiple copies of an image shifted attitudes to art (Benjamin 1936). Formerly unique objects, located in a particular place, lost their singularity as they became accessible to many people in diverse places. Lost too was the ‘aura’ that was attached to a work of art which was now open to many different readings and interpretations. For Benjamin, whether operating to allow more people to view likenesses of persons, places or existing objects (for instance, reproductions of paintings or sculptures) or facilitating novel forms of visual communication that might not otherwise have occurred, photography was inherently more democratic than previous forms of image-making. Yet established attitudes persist. In Western art the artist is accorded the status of someone endowed with particular sensitivities and vision. That the photographer as artist, viewed as a special kind of seer, chose to make a particular photograph lends extra authority and credibility to the picture.

In the twentieth century, photography continued to be ascribed the task of ‘realistically’ reproducing impressions of actuality. Writing after the Second World War in Europe, German critic Siegfried Kracauer and French critic André Bazin both stressed the ontological relation of the photograph to reality (Bazin 1967; Kracauer 1960). Walter Benjamin was among those who had disputed the efficacy of the photograph in this respect, arguing that the reproduction of the surface appearance of places tells us little about the sociopolitical circumstances which influence and circumscribe actual human experience (Benjamin 1931).

The photograph, technically and aesthetically, has a unique and distinctive relation with that which is/was in front of the camera. Analogical theories of the photograph have been abandoned; we no longer believe that the photograph directly replicates circumstances.

Siegfried Kracauer

(1889–1966) German critic, emigrated to America in 1941. His first major essay on photography was published in 1927 in the Frankfurter Zeitung. The subtitle of his best-known work Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality indicates his focus on images as sources of historical information. Benjamin’s renowned ‘Short History of Photography’ (1931), along with his ‘artworks’ essay (1936), was, in effect, a response to Kracauer’s 1927 essay.

Walter Benjamin (1931)

‘A Short History of Photography’ in (1979) One Way Street, London: New Left Books.

Yet, technologically, the photographic image is an indexical effect based on observable reality. The chemically produced image brought together a range of considerations – including subject-matter, framing, light, characteristics of the lens, chemical properties of the film used and the paper on which a picture was printed, and creative decisions taken both when shooting and in the darkroom. The digital image differs in certain respects, including the greater diversity of image manipulation possibilities, and the visual effect of the surface of the computer screen when compositing, editing and viewing. None the less, the basis in the observable fuels realist notions associated with photography, despite our familiarity with digital manipulation possibilities. Paradoxically, perhaps, we want to believe what we see, even though at the same time we know that photographic images are selective, and may be significantly changed from that originally seen through the viewfinder.

Italian semiotician Umberto Eco has commented that the photograph reproduces the conditions of optical perception, but only some of them (see Eco in Burgin 1982). That the photograph appears iconic not only contributes an aura of authenticity, it also seems reassuringly familiar. The articulation of familiar-looking subjects through established aesthetic conventions further fuels realist notions associated with photography.

Related to this are the interests and motivations that impel photographers towards particular subjects and ways of working. Very many biographies have been written purporting to explain photographs through the investigation of photographers’ personal experiences and political engagements; all too often tribute to the photographer and a particular way of seeing outweighs more critical analysis of the affects and import of a particular body of work. Yet questions of motivation and the contexts and constraints within which photographers operate clearly influence picture-making. Whilst not writing biographically, questions of motivation are woven within Geoff Dyer’s reflections on the nature of photographs (Dyer 2005). Why might a particular subject be chosen, and why do some types of object, pose or place seem to be repeated so often? As a cultural critic he comments that in trying to construct a taxonomy of photographs he found endless slippages and overlaps. This led him towards appraisal of photography via what can be known, or speculated, about the motivations of photographers. His examples are largely restricted to well-known American practitioners, and to documentary modes, yet his musings have wider pertinence as he provokes us to reflect upon the historical emergence of certain themes and subject-matter, and the evolving attitudes towards decorum or explicitness of image-content. Questioning why a photographer might have made and published a particular image is one starting point for thinking about the significance of particular photographs or types of photography.

Thus philosophical, technical and aesthetic issues – along with the role accorded to the artist – all feature within ontological debates relating to the photograph. But in recent years, developments in computer-based image production and the possibilities of digitisation and reworking of the photographic image have increasingly called into question the idea of documentary realism. The authority attributed to the photograph is at stake. That this has led to a reopening of debates about ‘photographic truth’ in itself shows that, in everyday parlance, photographs are still viewed as directly referencing actual observable circumstances.

See ch. 2 for further discussion.

Photography was born into a critical age, and much of the discussion of the medium has been concerned to define it and to distinguish it from other practices. There has never, at any one time, been a single object, practice or form that is photography; rather, it has always consisted of different kinds of work and types of image which in turn served different material and social uses. Yet discussion of the nature of the medium has often been either reductionist – looking for an essence which transcends its social or aesthetic forms – or highly descriptive and not theorised.

Photography was a major carrier and shaper of modernism. Not only did it dislocate time and space, but it also undermined the linear structure of conventional narrative in a number of respects. These included access to visual information about the past carried by the photograph, and detail over and above that normally noted by the human eye. Writing in 1931, Walter Benjamin proposed that the photograph records the ‘optical unconscious’:

It is indeed a different nature that speaks to the camera from the one which addresses the eye; different above all in the sense that instead of a space worked through by a human consciousness there appears one which is affected unconsciously. It is possible, for example, however roughly, to describe the way somebody walks, but it is impossible to say anything about that fraction of a second when a person starts to walk. Photography with its various aids (lenses, enlargement) can reveal this moment. Photography makes aware for the first time the optical unconscious, just as psychoanalysis discloses the instinctual unconscious.

(Benjamin 1972: 7)

Benjamin was writing at a time when the idea that photography offered a particular way of seeing took on particular emphasis; in the 1920s and 1930s both the putative political power of photography and its status as the most important modern form of communication were at their height. Modernism aimed to produce a new kind of world and new kinds of human beings to people it. The old world would be put under the spotlight of modern technology and the old evasions and concealments revealed. The photo-eye was seen as revelatory, dragging ‘facts’, however distasteful or deleterious to those in power, into the light of day. As a number of photographers in Europe and North America stressed, albeit somewhat differently, another of its functions was to show us the world as it had never been seen before. Photographers sought to offer new perceptions founded in an emphasis upon the formal ‘geometry’ of the image, both literally and metaphorically offering new angles of vision. The stress on form in photographic seeing typical of American modern photography parallels the stress on photography, and on cinematography (kino-eye), as a particular kind of vision in European art movements of the 1920s. Our ways of seeing will be changed because we can observe the world from unfamiliar viewpoints, for instance, through a microscope, from the top of high buildings, from under the sea. Moreover, photography validated our experience of ‘being there’, which is not merely one of visiting an unfamiliar place, but of capturing the authentic experience of a strange place. Photographs are records and documents which pin down the changing world of appearance. In this respect the close kinship between the still image and the movie is relevant; photography and film were both implicated in the modern stress on seeing as revelation. Indeed, artists and documentarians frequently used both media.

halftone By the mid-1890s ‘halftone’, based on tiny dots of various sizes, could facilitate the tracing of tones of photographs into ink ready for mechanical reproduction alongside written text. Previously engravers were employed in the laborious process of tracing and gouging out images on wooden blocks that were then inked to enable printing. The halftone allowed newspapers and magazines to use up-to-date photo illustrations, enabling mass circulation of imagery, in effect contributing a basis for photojournalism.

In addition, photography was centrally implicated in the burgeoning of print media that dated from the early years of the twentieth century. It was precisely this mass circulation of images that allowed Benjamin to conceptualise photography as a democratic medium. Arguably it was what was happening on the printed page that excited imagination at the beginning of the twentieth century. Posters, photomontage, and – later – photographic magazines such as Time, Life, Picture Post, Vue offered opportunities for experi mentation with image juxtapositions and modes of visual story-telling. However, as David Campany notes in an account of the work of American photographer, Walker Evans, by their very nature, magazines are transient. He suggests that,

The photobook form always has at least half an eye on posterity but the illustrated magazine has a very different temporality and culture significance. It is not made to last, but lives and dies, succeed or fails in the space of its short shelf life.

(Campany in di Bello et al., 2012: 73)

He goes on to argue that the reproduction of documentary and photo-journalistic images made for publication that were ‘essentially ephemeral’ but later singled out for exhibition in museums or inclusion in monographs ‘does little to capture the contingent complexity of their initial page presentation’ (loc cit) remarking that it is only in the beginning of the twenty-first century that researchers have started to consider the history of photo-magazines along with that of the photobook. In some respects this is accurate. But we might also note the influence of photomontage and poster campaigns typical of early Soviet photography on uses of photography within 1970s and 1980s political activism in Britain, Germany, USA and elsewhere.

Indeed, European modernism, with its contempt for the aesthetic forms of the past and its celebration of the machine, endorsed photography’s claim to be the most important form of representation. Moholy-Nagy, writing in the 1920s, argued that now our vision will be corrected and the weight of the old cultural forms removed from our shoulders:

Everyone will be compelled to see that which is optically true, is explicable in its own terms, is objective, before he can arrive at any possible subjective position. This will abolish that pictorial and imaginative association pattern which has remained unsuperseded for centuries and which has been stamped upon our vision by great individual painters.

(Moholy-Nagy 1967: 28)

Modernist photography was grounded in the sweeping away of pictorialism and the rejection of all attempts to simulate ‘artistic’ forms. As with the radical shift that modernism brought about in music, literature, architecture and art, the photographic image was to be a reflexive, self-conscious medium which revealed its own, particular properties to the viewer. This way of working spread around the world, so that (for example) modernist photography in Europe, the USA, Latin America and India can all be studied. But modernism was not a simple blueprint that all societies copied; its particular forms in specific places emerged in response to already existing cultures and histories. The aspiration that a world cleansed of traditional forms and hierarchies of values would be established, one in which we would be free to see clearly without the distorting aesthetics of the past, had to contend with the pressures and embodied histories of existing societies. However, the transformative power of modernism did seem to many to be heralding a new world as exemplified by Paul Strand when he described American photographic practice, which he saw as indi genous and viewed as being as revolu tionary as the skyscraper. As he put it in a famous article in the last issue of Camera Work:

America has been expressed in terms of America without the outside influence of Paris art schools or their dilute offspring here … [photography] found its highest esthetic achievement in America, where a small group of men and women worked with honest and sincere purpose, some instinctively and a few consciously, but without any background of photographic or graphic formulae much less any cut and dried ideas of what is Art and what isn’t: this innocence was their real strength. Everything they wanted to say had to be worked out by their own experiments: it was born of actual living. In the same way the creators of our skyscrapers had to face the similar circumstances of no precedent and it was through that very necessity of evolving a new form, both in architecture and photography that the resulting expression was vitalised.

(Strand 1917: 220)

Here, then, in a distinctively American formulation, photography is seen as having been developed outside history. Strand is claiming that a new frontier of vision was established by hard work and a kind of innocence, that it was a product of human experience rather than of cultural inheritance.

Postmodernism was an important, and much contested philosophical term, which emerged in the mid-1980s. It remains difficult to define, not least because it was applied to very many spheres of activity and disciplines. Briefly, writers on postmodernism postulated the idea that modernity had run its course, and was being replaced by new forms of social organisation with a transforming influence on many aspects of existence. Central to the growth of this kind of social formation was the development of information networks on a global scale which allowed capital, ideas, information and images to flow freely around the world, weakening national boundaries and profoundly changing the ways in which we experience the world.

Among the key concepts of postmodernism were the claims that we are at the ‘end of history’ and that, as Jean-François Lyotard suggested, we are no longer governed by so-called ‘grand’ or ‘master’ narratives – the under pinning framework of ideas by means of which we had formerly made sense of our existence. For instance, Marxism in emphasising class conflict as the dialectical motor of history, provides a material philosophical position which can be drawn upon to account for any number of sociopolitical phenomena or circum stances (Lyotard 1985). This critique was accompanied by the assertion that there has been a major shift in the nature of our identity. Eighteenth-century ‘Enlightenment’ philosophy saw humans as stable, rational subjects. Post modernism shares with modernism the idea that we are, on the contrary, ‘decentred’ subjects. The word ‘subjects’, here, is not really concerned with us as individuals, but refers to the ways in which we embody and act out the practices of our culture. Some postmodernist critics argued that we are cut loose from the grand narratives provided by history, philosophy or science; so that we live in fragmented and volatile cultures. This view was supported by the postmodern idea that we inhabit a world of dislocated signs, a world in which the appearance of things has been separated from authentic originals.

Writing over a century earlier in 1859, the American jurist and writer Oliver Wendell Holmes had considered the power of photography to change our relationship to original, single and remarkable works:

There is only one Coliseum or Pantheon; but how many millions of potential negatives have they shed – representatives of billions of pictures – since they were erected! Matter in large masses must always be fixed and dear; form is cheap and transportable. We have got the fruit of creation now and need not trouble ourselves with the core. Every conceivable object of Nature and Art will soon scale off its surface for us. We will hunt all curious, beautiful grand objects, as they hunt the cattle in South America, for their skins, and leave the carcasses as of little worth.

(Holmes 1859: 60)

Holmes did conceive of some essential difference between originals and copies. Nevertheless, he realised that the mass trade in images would change our relationship to originals; making them, indeed, little more than the source of representation.

The postmodern was not concerned with the aura of authenticity. For example, in Las Vegas hotels are designed to reference places such as New York or Venice, featuring ‘Coney Island’ or ‘The Grand Canal’. Superficially the resemblance is impressive in its grasp of iconography and semiotics, specifically, in understanding that, say, Paris, can be conjured up in a con densed way through copying traditional (kitsch) characteristics, for example, of Montmartre. Actual histories, geographies and human experiences are not only obscured, they are irrelevant, as these reconstructions are essentially décor for commercialism: gambling, shopping, eating and drinking. Indeed, communications increasingly featured what the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard called ‘simulacra’: copies for which there was no original.

Jean Baudrillard

(b.1929) French philosopher, Jean Baudrillard, has theorised across a very wide terrain of political, social and cultural life. In his early work he attempted to move Marxist thought away from a preoccupation with production and labour to a concern with consumption and culture. His later work looks at the production and exchange of signs in a spectacular society. His notions of the hyperreal and of the simulacrum are of great interest to those interested in theorising photography, and were among the core concepts of postmodernism.

In a world overwhelmed by signs, what status is there for photography’s celebrated ability to reproduce the real appearance of things? Fredric Jameson argues that photography is:

renouncing reference as such in order to elaborate an autonomous vision which has no external equivalent. Internal differentiation now stands as the mark and moment of a decisive displacement in which the older relationship of image to reference is superseded by an inner or interiorized one … the attention of the viewer is now engaged by a differential opposition within the image itself, so that he or she has little energy left over for intentness to that older ‘likeness’ or ‘matching’ operation which compared the image to some putative thing outside.

(Jameson 1991: 179)

He was among a number of contemporary critics who argue that photography has given up attempting to provide depictions of things which have an autonomous existence outside the image and that we as spectators no longer possess the psychic energy needed to compare the photograph with objects, persons or events in the world external to the frame of the camera. If a simulacrum is a copy for which there is no original; it is, as it were, a copy in its own right. Thus, in postmodernity, the photograph had no necessary referent in the wider world and could be understood or critiqued only in terms of its own internal aesthetic organisation.

This separation of the image from its referent crucially underpins the way in which we can think about the digital image. In analogue photography a picture was formed through transcription, in principle tracing or witnessing actual people, places and circumstances (although, of course, selection, cropping, image retouching and other processes could be used to adjust the image content and qualities). Digital photography operates through a conversion whereby physical properties are symbolised through numerical coding (see pp. 367–8). Furthermore, digital ‘photographs’ can be constructed with no reference to external phenomena. In practice, photography has become hybrid in that we continue to compose pictures in documentary idiom, but can amend and adjust – not to mention, delete – with great ease. The photographs that we see nowadays are normally digital. Yet we continue to ascribe authenticity to photographic images (whether our own personal photographs, photo-journalism, forensic photography, travel and tourism, and so on). As Roland Barthes argued, the photograph is always and necessarily of something (Barthes 1984: 28). But arguably the basis of our belief in photographs has shifted (see discussion in the next section of this chapter).

The advent of the digital has led to a greater integration of industries and practices. As Martin Lister pointed out in relation to professional spheres of photography,

In the period since the 1990s, ‘digital photography’ and ‘digital imaging’ have developed as major creative industries, and have become a taken-for-granted part of the media landscape. The once firm separations between older twentieth-century specialist divisions of skill and labour have become permeable, especially between photography, typographic and graphic design, project management, editorial work, and still and moving image production. Even for those professional photographers who continue to use film for some of its distinctive properties, digital technologies and processes are now an essential part of their post-production practices.

For many others, digital technologies have replaced analogue processes: traditional cameras are replaced by digital and even virtual kinds, films by memory cards and hard drives, ‘wet’ physical darkrooms and optical enlargers by computers and software.

(Lister 2013: 313)

More generally, digital cameras, mobile phones and computer photo applications have become ubiquitous, and the use of data storage facilities for and social media modes of communication are normal, certainly in parts of the world with ready access to electricity and internet connections. As Lister also remarked,

The snapshots once pasted into the traditional family photo-album are now stored in electronic ‘shoe-boxes’, the majority never taking a ‘hard-copy’ form, to be displayed instead on the screens of televisions, personal computers, or the LCD screens of the very cameras with which they are taken.

(Lister 2013: 315)

Here again, the inter-relation of aesthetics and technologies is evident. For instance, an image viewed on a computer screen acquires a translucence that rarely characterizes a traditional printed version, and the scale of images tends to become uniform as the same appliance is used for viewing images of very different types, from those constructed as online commercial advertisements to panoramic landscapes reflecting the environmental concerns that preoccupy several contemporary artist-photographers.

Some photography does not traffic in multiple images but, rather, is constructed for the gallery. Cultural theorist Rosalind Krauss has described photography’s relationship to the world of aesthetic distinction and judgement in the following terms:

Within the aesthetic universe of differentiation – which is to say; ‘this is good, this is bad, this, in its absolute originality, is different from that’ – within this universe photography raises the specter of nondifferentiation at the level of qualitative difference and introduces instead the condition of a merely quantitative array of difference, as in series. The possibility of aesthetic difference is collapsed from within and the originality that is dependent on this idea of difference collapses with it.

(Krauss 1981: 21)

Like Benjamin she noted the loss of aura introduced by the mass reproducability of photographs, but here she draws attention to the impact of this inherent characteristic within the gallery and the art market. The ‘collapse of difference’ has had an enormous effect on painting and sculpture, for photography’s failure of singularity undermined the very ground on which the aesthetic rules that validated originality was established. Multiple, reproducible, repetitive images destabilised the very notion of ‘originality’ and blurred the difference between original and copy. The ‘great masters’ approach to the analysis of images becomes increasingly irrelevant, for in the world of the simulacrum what is called into question is the originality of authorship, the uniqueness of the art object and the nature of self-expression.

Indeed, in a world wherein images, which appear increasingly mutable, circulate electronically, such issues may seem irrelevant. Most of us now experience some of the effects of the ongoing digital revolution. Many of us receive photographs on e-mail, send them via mobile phones, store them in electronic archives, combine them with text to create brochures, or manipulate them to enhance their quality. Photography has always been caught up in new technologies and played a central part in the making of the modern world. However, one feature of the digitisation of many parts of our life is that potential new technologies are discussed in detail long before they become an everyday reality. In terms of photography many people anticipated a loss of confidence in the medium because of the ease with which images could be seamlessly altered and presented as accurate records. That this does not appear to have happened is testimony to the complex ways in which we use and interpret photographs. Nevertheless, these technologies are having a decided impact on the nature of the medium and are changing the ways in which it is used in all spheres of life. These changes continue to be made as the complex mix of technologies leads to the production of new products, stimulates new desires and evolves new forms of communication.

Writing about the problem of attention, Jonathan Crary makes it clear that each new technological form is not simply an extension of a stable, unchanging, quality of human vision. Instead, he argues that:

If vision can be said to have any enduring characteristic within the twentieth century, it is that it has no enduring features. Rather it is embedded in a pattern of adaptability to new technological relations, social configurations, and economic imperatives. What we familiarly refer to, for example, as film, photography and television are transient elements within an accelerating sequence of displacements and obsolescences, part of the delirious operations of modernization.

(Crary 1999: 13)

In this account the old notion of particular ways of seeing (of a ‘photo-eye’, for example) gives way to the idea of vision as a mutable faculty that is constantly adapting to a cluster of social and technical forces, while apparently stable forms such as photography or television are themselves being continuously transformed.

The first myth to dispel about ‘theory’ is the idea that we can do without it. There is no untheoretical way to see photography. While some people may think of theory as the work of reading difficult essays by European intellectuals, all practices presuppose a theory.

(Bate 2009: 25)

The purpose of theory is to explain. All discussions of photographs rest upon some notion of the nature of the photographic and how images acquire meaning. Theory offers a system or set of tools whereby we can understand objects, processes and the implications of imagery. The issue is not whether theory is in play but, rather, whether theory is acknowledged. Two strands of theoretical discussion particularly featured in debates about photography towards the end of the twentieth century: first, theoretical approaches premised on the relationship of the image to reality; second, those which stress the importance of the interpretation of the image by focusing upon the reading, rather than the making, of photographic representations. In so far as there has been crossover between these two strands, this is found in the recent interest in the contexts and uses of images.

‘Theory’ refers to a coherent set of understandings about a particular issue that have been, or potentially can be, appropriately verified. It emerges from the quest for explanation and reflects specific intellectual and cultural circumstances. Theoretical developments occur within established paradigms, or manners of thinking, which frame and structure the academic imagination. On the whole, modern Western philosophy, from the eighteenth century onwards, has stressed rational thought and posited a distinction between subjective experience and the objective, observable or external. One consequence of this has been positivist approaches to research both in the sciences and the social sciences; indeed, photography as a recording tool has been centrally implicated within notions of the empirical. (See ch. 2.) Positivism has not only influenced uses of photography; it has also framed attitudes towards the status of the photograph.

Academic interrogation of photography employs a range of different types of theoretical understandings: scientific, social scientific and aesthetic. Historically, there has been a marked difference between scientific expectations of theory, and the role of theory within the humanities. Debates within the social sciences have occupied an intellectual space which has drawn upon both scientific models and the humanities. In the early/mid-twentieth century literary criticism centred upon a canon of key texts deemed worthy of study. Similarly, art history was devoted to a core line of works of ‘great’ artists, and much time was given to discussion of their subject-matter, techniques, and the provenance of the image. The academic framework was one of sustaining a particular set of critical standards and, perhaps, extending the canon by advocating the inclusion of new or newly rediscovered works. A number of major exhibitions and publications on photography have taken this as their model, offering exposition of the work of selected photographers as ‘masters’ in the field. This approach, in literature, art history and aesthetic philosophy, has been critiqued for its esoteric basis. It has also been criticised for reflecting white, male interests and, indeed, for blinkering the academic from a range of potential alternative visual and other pleasures. For instance, within photography the fascination of domestic or popular imagery, in its own right as well as within social history, was long overlooked, largely because such images do not necessarily accord with the aesthetic expectations of the medium and because they tend to be anonymous.

A more systematic critical approach, associated with mainland European intellectual debates, penetrated the Anglo-American tradition in some areas of the humanities, especially philosophy and literary studies, in the 1970s. The parallel influence on visual studies came slightly later. This impact was most pronounced in the relatively new – and therefore receptive – discipline of film studies. But there was also a significant displacement of older, established preoccupations and methods within art history and criticism. Increasingly, methodologically more eclectic visual cultural studies have superseded the more limited focus of traditional art history and aesthetic philosophy although, as has been argued in particular by Geoffrey Batchen, art-historical methods and presumptions have to some extent dominated photo-analysis, leading to an emphasis on photographs as images and thereby displacing critical engagement with photographs as material objects (Batchen 2007, 2008; di Bello 2007). Batchen’s exhibition, Forget Me Not – Photography and Remembrance paid specific attention to various forms in which photography may be physically manifest, from ornate framing, family albums and images in lockets, to lamp-shades or cushions (Batchen 2004).

Indeed, within visual studies there has been an increased interest in the phenomenological, in ways in which other senses, particularly touch and the tactile, interact with the sight contributing to how photographs, as objects as well as images, affect us. As Elizabeth Edwards succinctly suggests:

Photographs are the focus of intense emotional engagement. In premising photographic effect on the visual and the forensic alone, we limit our understanding of the modes through which photographs have historical effect because photographs both focus and extend the verbal articulation of histories and the sound world they inhabit.

(Edwards 2008: 241)

David Bate (2009)

Photography, The Key Concepts. Oxford and New York: Berg. An introductory guide to conceptual issues that includes sections on history, theory, documentary and story-telling and globalization, as well as overviewing selected genres in photography.

In Photography: The Key Concepts David Bate defines three periods in the development of theory relating to photographic practices and the significance of photographic imagery: Victorian aesthetics, mass reproduction in the early twentieth century and critical debates of the 1960s and 1970s that, as he phrases it, ‘rippled over’ into discussions of the postmodern in the 1980s. We might also add a fourth period of theoretical debates wherein the photographic became implicated within ways of thinking about digital imaging and virtual space. His use of the term ‘rippled’ is significant; it reminds us that the framing of particular debates, and of positions argued, is not neatly contained within any one period of history or, indeed, in specific places and contexts. Ideas and positions maybe re-inflected, threading their way into subsequent debates. Here the Hegelian notion of dialectics is useful in suggesting that a thesis and antithesis (anti-thesis) may become synthesised into a position that itself becomes a new starting point or thesis for further critical reflections. Singular dialectical thinking offers too linear a notion of philosophical processes given the cultural complexities of cultural circumstances including spillages between the local and the global, the virtual and the real. Jae Emerling utilises the metaphor of a game of chess as a means of conveying the complexity of the inter-relations of discourses pertinent to critical reflections on photography; each piece moves according to specific allocated rules and each move changes the overall pattern of relations (Emerling 2012). The analogy is pertinent although perhaps fails to indicate the sense of speed and fluidity of change that characterises contemporary digital environments within the global context. Arguably for dialectics to remain intellectually useful we need to think of reflective processes as analogous to a continuously spinning web of intersecting lines of dialectical reflections and developments.

One of the central difficulties in the establishment of photography theory, and of priorities within debates relating to the photographic image, is that photography lies at the cusp of the scientific, the social scientific and the human ities. Thus, contemporary ontological debates relating to the photograph are divergent. One approach centres on analysis of the rhetoric of the image in relation to looking, and the desire to look. This is premised on models of visual communication which draw upon linguistics and, in particular, psychoanalysis. This approach locates photographic imagery within broader poststructuralist concerns to understand meaning-producing processes.

Up until the 1980s ‘photography theory’ within education had been taken to refer to technologies and techniques as in optics, colour temperature, optimum developer heat, etc. ‘Theory’ related to the craft base of photography. In introducing the collection of essays Thinking Photography, artist/critic Victor Burgin argued that photography theory must be interdisciplinary and must engage not only with techniques but, more particularly, with processes of signification (Burgin 1982). Writing in the context of the 1970s and 1980s, and drawing on work from a range of disciplines, he commented that photography theory does not exist in any adequately developed form. Rather, we have photography criticism which, as currently practised, was evaluative and normative, authoritative and opinionated, reflecting what he terms an ‘uneasy and contradictory amalgam’ of Romantic, Realist and Modernist aesthetic theories and traditions. We might ask to what extent this is different now, a quarter of a century later. He also suggested that photography history, as written up until the 1980s, reflects the same ideological positions and assumptions; that is to say, it uncritically accepts the dominant paradigms of aesthetic theory. Burgin warns against confusing photography theory with a general theory of culture, arguing for the specificity of the still, photographic image.

Victor Burgin (ed.) (1982)Thinking Photography, London: Macmillan. A collection of eight essays, including three by Burgin himself, which, although varying in theoretical stance and focus, all aim to contribute to developing a materially grounded analysis of photographic practices.

In relation to this, as we have already seen, a number of critics have focused on the realist properties of the image. Film critic André Bazin in the 1950s, in his key essay on the subject, emphasised the truth-to-appearances characteristics of the photographic (Bazin 1967). Albeit within wider-ranging terms, Susan Sontag, in her 1970s series of essays collected as On Photography, also discussed photographs as traces of reality and interrogated photography in terms of the extent to which the image reproduces reality. Similarly, Roland Barthes emphasised the referential characteristics of the photograph in his final book Camera Lucida (Barthes 1984).

Susan Sontag (2002)On Photography, Harmondsworth: Penguin, new edition with introduction by John Berger. A collection of six essays on various aspects of photography which, despite seeming slightly out of date in its concern with realism, still offers many key insights. Her programme on photography, It’s Stolen Your Face, produced for the BBC in 1978, was based on this collection.

Roland Barthes (1984) Camera Lucida, London: Fontana. First published in French in 1980 as La Chambre Claire. In this, his final book, Barthes offers a quite complex, rhetorical, but nonetheless interesting and significant set of comments on how we respond to photographs.

Photographing is essentially an act of non-intervention.

(Sontag 1979: 11)

Because of the disjunction between the thinking, seeing photographer and the camera that is the instrument of recording, the viewer finds it more difficult than with other visual artifacts to attribute creativity to any photographer.

(Price 1994: 4)

In philosophical terms, any concern with truth-to-appearances or traces of reality presupposes ‘reality’ as a given, external entity. Notions of the photograph as empirical proof, or the photograph as witness offering descriptive testimony, ultimately rest upon the view of reality as external to the human individual and objectively appraisable. If reality is somehow there, present, external, and available for objective recording, then the extent to which the photograph offers accurate reference, and the significance of the desire to take photographs or to look at images of particular places or events, become pertinent.

Despite the broader promise of its title, Photography Theory, edited by James Elkins, centres primarily on the photograph as image and on the indexical, that is, ways in which the image stands as a reference to or trace of actual phenomena (Elkins 2007). His focus is on photography as art; everyday photographic phenomena and practices are not core considerations, although, as many photography theorists have argued, contexts in which we view photographs, what we want of particular images (for instance, of family, friends, places, or celebrities), and how they relate to broader contemporary debates and currencies (for example, political concerns, or new phenomena within popular culture) are equally as significant as the image in itself. But the publication offers an example of ways in which the relation between the image and its referent continues to pre-occupy photo theorists

Susan Sontag defined the photograph as a ‘trace’ directly stencilled off reality, like a footprint or a death mask. On Photography offered a series of interconnected essays, essentially based on a realist view of photography. Her concern was with the extent to which the image adequately represents the moment of actuality from which it is taken. She emphasised the idea of the photograph as a means of freezing a moment in time. If the photograph misleads the viewer, she argued this is because the photographer has not found an adequate means of conveying what he or she wishes to communicate about a particular set of circumstances. Her focus was on the photograph as document, as a report, or as evidence of activities such as tourism. She commented that the use of a camera satisfies the work ethic and stands in when we are unsure of our responses to unfamiliar circumstances, but can also reduce travel and other experiences to a search for the photogenic. Sontag also discussed the ethics of the relationship between the photographer as reporter and the person, place or circumstances recorded. The photographer, especially the photojournalist, is relatively powerful within this relationship, and thus may be seen as predatory. She pointed out that the language of military manoeuvre – ‘load’, ‘shoot’ – is central to photographic practices. Given this relative power, in her view it is even more important to emphasise the necessity of accurate reporting or relating of events. Photographs are not necessarily sentimental, or candid; they may be used for a variety of purposes including policing or incrimination.

Sontag’s discussion veers between the reasons for taking photographs and the uses to which they are put. It is marked by a sense of the elusiveness of the photo-image itself. She noted our reluctance to tear up photos of rela tives, and the rejection of politicians through symbolically burning images. She describes photographs as relics of people as they once were, suggesting that the still camera embalms (by contrast with the movie camera, which savours mobility). Thus she drew attention to the fascination of looking at photographs in terms of what we think they may reveal of that which we cannot otherwise have any sense of knowing, characterising photographs as a catalogue of acquired images which stand in for memories. Photographs can also, she suggests, give us an unearned sense of understanding things, past and present, having both the potential to move us emotionally, but also the possibility of holding us at a distance through aestheticising images of events. Photographs can also exhaust experiences, using up the beautiful through rendering it into cliché. For instance, she notes that sunsets may now look corny; too much like photographs of sunsets. The overall impact of her essays is rhetorical in that she makes grand claims for photography as a route to seeing, and, by extension, understanding more about the world of experience. Throughout, we have the sense that meaning may be sought within the photograph, providing it has been well composed and therefore accurately traces a relic of a person, place or event. Yet the collection does not include examples of actual photographs and there is no detailed analysis and discussion of specific images.

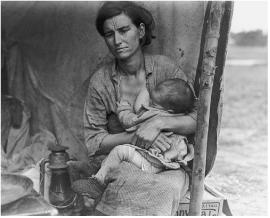

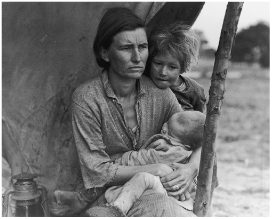

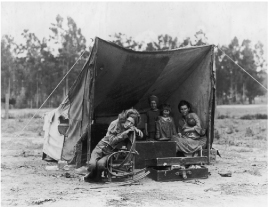

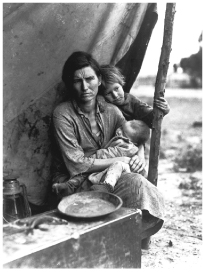

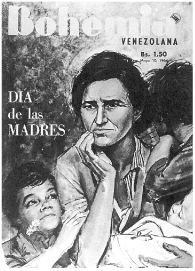

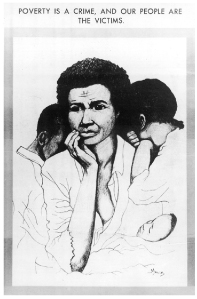

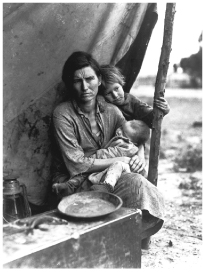

In her book The Photograph: A Strange, Confined Space (1994), American critic, Mary Price, argued that the meaning of the photographic image is primarily determined through associated verbal description and the context in which the photograph is used. By contrast with Sontag’s emphasis on the relation between the image and its source in the actual historical world, Price starts from questions of viewing and the context of reception. Thus, she suggests, in principle there is no single meaning for a photograph, but rather an emergent meaning, within which the subject-matter of the image is but one element. Her analysis is practical in its approach. She takes a number of specific examples, aiming to demonstrate the extent to which usage and contextualisation determine meaning. Related to this, in No Caption Needed, Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites discuss iconicity and photographs as public art through focusing on nine examples of pictures, with documentary or photojournalistic origins, that have become iconic; photographs for which meaning now transcends the specific circumstances of their making as they have come to represent particular ideologies or political attitudes (Hariman and Lucaites 2007). Whilst meaning may once have been anchored through context and caption, as we shall demonstrate in the case study of Dorothea Lange’s ‘Migrant Mother’ 1936 (see below), many further references become woven into what such an image has subsequently come to connote. This study is significant for its analysis of ways in which photographs may acquire political significance through reference to collective memory.

Robert Hariman And John Louis Lucaites (2007) No Caption Needed, Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Realist theories of photography, then, can take a number of different starting points: first, the photograph itself as an aesthetic artefact; second, the institutions of photography and the position and behaviour of photographers; third, the viewer or audience and the context in which the image is used, encountered, consumed. The particular starting point organises investigative priorities. For instance, ethical questions relating to who has the right to represent whom are central when considering the photographer and institutions such as the press.

Sontag takes a particular position within debates about realism, stressing the referential nature of the photographic image both in terms of its iconic properties and in terms of its indexical nature. For Sontag, the fact that a photograph exists testifies to the actuality of how something, someone or somewhere once appeared. Max Kozloff challenged Sontag’s conceptual model, criticising her proposition that the photograph ‘traces’ reality, and arguing instead for a view of the photograph as ‘witness’ with all the possibilities of misunderstanding, partial information or false testament that the term ‘witness’ may be taken to imply (Kozloff 1987: 237). In his earlier collection of essays, Photography and Fascination, Kozloff starts from the question of the enticement of the photograph. He concludes that:

Though infested with many bewildering anomalies, photographs are considered our best arbiters between our visual perceptions and the memory of them. It is not only their apparent ‘objectivity’ that grants photographs their high status in this regard, but our belief that in them, fugitive sensation has been laid to rest. The presence of photographs reveals how circumscribed we are in the throes of sensing. We perceive and interpret the outer world through a set of incredibly fine internal receptors. But we are incapable, by ourselves, of grasping or tweezing out any permanent, sharable figment of it. Practically speaking, we ritually verify what is there, and are disposed to call it reality. But, with photographs, we have concrete proof that we have not been hallucinating all our lives.

(Kozloff 1979: 101)

However the relation between the image and the social world is conceptualised, it is worth noting that the authority that emanates from the sense of authenticity or ‘truth to actuality’ conferred by photography was a fundamental element within photographic language and aesthetics. This authority, founded in realism, came to be taken for granted in the interpretation of images made through the lens.

It is precisely this that sets lens-based imagery apart from other media of visual communication. Again, to quote Kozloff, ‘A main distinction between a painting and a photograph is that the painting alludes to its content, whereas the photograph summons it, from wherever and whenever, to us’ (1987: 236). Chemical photography is distinct from the autographic, or from the digital, in that it seems to emanate directly from the external. Inherent within the photographic is the particular requirement for the physical presence of the referent. This has led to photographs (along with film and video) being viewed as realist in ways that, say, technical drawing or portrait painting are not (although they are also based upon observation).

That this was the case needs to be clearly acknowledged and addressed in order to understand theoretical debates as they were engaged historically as well as the legacies of this for contemporary debates. It is no coincidence that indexicality has become a contemporary focus of enquiry (for example, Elkins 2007). Perhaps one of the most curious facets of contemporary imaging is that, despite knowing the extent to which pictures can be and are manipulated and the ease with which this can be achieved through various software, we suspend disbelief and continue to ascribe authenticity to photographic images. What was – and remains – at stake in terms of provenance and authenticity in relation to the evidential authority of the photographic image continue to preoccupy many historians and theorists.

It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world, we explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it. The relationship between what we see and what we know is never settled.

(Berger 1972a: 7)

In the late twentieth century two key theoretical developments, semiotics and psychoanalysis, significantly contributed to changes within the humanities and both figured in debates relating to the constitution of photographic meaning. Semiotics (or semiology), the idea of a science of signs, originated from comments in Ferdinand de Saussure’s General Theory of Linguistics (1916) but was not further developed until after the Second World War. Essentially, semiotics proposed the systematic analysis of cultural behaviour. At its extremes it aimed at establishing an empirically verifiable method of analysis of human communication systems. Thus, codes of dress, music, advertising – and other forms of communication – are conceptualised as logical systems. The focus is upon clues which together constitute a text ready for reading and interpretation. American semiotician C.S. Peirce further distinguished between iconic, indexical and symbolic codes. Iconic codes are based upon resemblance, for instance, a picture of someone or something; indexical codes are effects with specific causes, for example, footprints indicate human presence; symbolic codes are arbitrary, for instance, there is no necessary link between the sound of a word and that to which it refers.

The key limitation of semiotics as first proposed, with its focus upon systems of signification, was that it failed to address how particular readers of signs interpreted communications, made them meaningful to themselves within their specific context of experience. It became common to use the term ‘semiology’ to refer to the earlier, relatively inflexible approach based upon structuralist linguistics, and to use ‘semiotics’ to indicate later, more fluid models, incorporating psychoanalysis, wherein the focus is more upon meaning-producing processes than upon textual systems. Social semiotics, taking account of questions of interpretation and context, inflects the emphasis specifically towards cultural artefacts and social behaviour.

Roland Barthes was known for his contribution to the semiological analysis of visual culture, in particular from his early work, Mythologies. Working inductively from his observations of differing cultural phenomena, he proposed that everyday culture could be analysed in terms of language of communication (visual and verbal) and integrally associated myths or culturally specific discourses. The central objective of this early work was the development of all-encompassing models of analysis of meaning-production processes. Later works, including The Pleasure of the Text (1973) and Camera Lucida (1984), were no longer focussed on sentences or images as texts so much as on ways in which meaning might be deciphered. These works take more account of the individual reader, of processes of interpretation, of psychoanalytic factors, and of what we might term cultural ‘slippages’ – thereby implicitly accepting a degree of unpredictability in human agency or response.

Roland Barthes