3.1 Studio photograph of Lily Peapell in peasant dress on roller skates, c. 1912

Personal photographs and popular photography

Private lives and personal pictures: users and readers

In and beyond the charmed circle of home

The public and the private in personal photography

The working classes picture themselves

Kodak and the mass market: the Kodak path

Paths unholy and deeds without a name?

Post-family and post-photography? The digital world and the end of privacy

3.1 Studio photograph of Lily Peapell in peasant dress on roller skates, c. 1912

‘When amid life’s surging battle Reverie its solace lends Sweet it is to scan the faces – Picture faces – of old friends

…

Some have passed the mystic portals Where the usher Death presides Some to distant climes have wandered Borne on Time’s relentless tides; Some, perchance, to paths unholy; Some to deeds without a name But the faces in the album Are for aye and aye the same.

…

Picture faces! Oh what volumes Of unwritten life ye hold: Youthful faces! pure, sweet faces! Dearly prized as we grow old’

M.C. DUNCAN

Frontispiece to Richard Penlake

Home Portraits for Amateur Photographers (1899)

Personal photographs and popular photography

The doggerel, couched in the language of late Victorian sentiment, with its yearning for purity and sense of the closeness of death, fronted a book of advice for ‘amateur photographers’ just at the time when home photography was undergoing a dramatic transformation. The crafted work of the ‘gentle man amateur’ or hobbyist, whose proliferating equipment involved tripods, black cloths, glass plate negatives, special backdrops, darkrooms and a cocktail of chemicals, was giving way to an instant push-button affair, in which the film could be sent off for processing and no special skills were required. In 1888 George Eastman marketed his revolutionary hand-held Kodak with the cheery slogan ‘You press the button, we do the rest’ and was about to launch the ‘Box Brownie’ – the camera he claimed that everyone could afford and was easy enough for children to use. ‘Kodak’s advertising purged domestic photog raphy of all traces of sorrow and death’ writes Nancy Martha West (2000: 1). This was the beginning of an era when the ‘amateur’ photographer was likely to be a woman, interested in ‘home portraits’, records of family life and much else besides. The new technology of the day was bringing a revolu tion in ways of perceiving the immediate domestic world, and in redefining who had the right to record that world. Photography was being democratised.

Nancy Martha West (2000) Kodak and the Lens of Nostalgia, Virginia: University of Virginia Press.

Risto Sarvas And David Frohlich (2011) From Snapshots to Social Media: The Changing Picture of Domestic Photography, London: Springer.

Jonas Larsen And Mette Sandbye (eds) (2013) Digital Snaps: The New Face of Photography, London: I.B.Tauris.

A century later, digital technology was creating a new revolution in personal imagery. By the early 2000s ‘domestic’ photography was flowing far beyond the limits of the home. It was becoming more interactive, more interventionist, and more inclusive (Sarvas and Frohlich 2011; Lister (ed.) 2012: Larsen and Sandbye (eds) 2013). It was linking friends and relatives through social media and camera phones, and displaying itself proudly to the public at large on websites, such as Flickr.1 ‘Doing the rest’ is now as easy as ‘pressing the button’, and an even wider range of controls is in the hands of the home photographer. Huge numbers of domestic scenes are now recorded with unparalleled ease, and the images shared across the globe at the touch of a key. Sophisticated procedures that had been the preserve of the professional or the dedicated amateur are now available to a broad swathe of the population, and are taught to primary school children. There is an infinity of playful ways of manipulating and organising (and rearranging) personal pictures using simple computer programs, and of distributing them instantaneously. Pictures are less likely to be precious one-offs. They are more malleable, more disposable. In addition, digital technology has broadened perception both beyond the immediate and beyond the contemporary. History has been popularised, and family history has been re-framed and made more public. An explosion of interest in tracing ancestors and rediscovering pictures from the past has been fuelled by television programmes, numerous publications and specialist websites.2 And the past, too, can be reconstituted, too. Dead relatives can be scanned into contem porary pictures; family groups can be constructed which never existed in real life. When M.C. Duncan wrote ‘sweet it is to scan …’ he was thinking of the poignant experience of gazing at the present image of those who have ‘passed the mystic portals’ or ‘wandered to distant climes’. Little did he imagine the unique pleasure of digitally scanning such images to construct a more fluid perception of the gap between present and past. In sum, the twenty-first century has seen changes at every point in the creation, circulation and use of personal photographs.

Reviewing the development of domestic photography in the light of these changes, Risto Sarvas and David Frohlich have outlined a history of technological evolution in which an established ‘technological path’ is disrupted by a radical invention. This launches an ‘era of ferment’ and experimentation, but eventually settles to a new stable technological path. The invention of the hand-held Kodak was the disruption which moved domestic photography from what Sarvas and Frohlich describe as the ‘portrait path’ when personal pictures were largely taken in studios by professionals, to the ‘Kodak’ path, when anyone could press the button, because ‘we do the rest’. The era of ferment was brief, and ‘Kodak culture’ came to dominate photography for almost a century. However, in contrast to the 1890s, the radical inventions which launched the digital path in the 1990s initiated an extended period of ferment which still shows no sign of settling down (Sarvas and Frohlich 2011:13–21). The uncertainty and confusion which accompany attempts to describe and account for the personal uses of photography in the twenty-first century are to a large extent a result of this continuing ferment, and have been frequently accompanied by a sense of loss, as the immaterial digital image replaces a material and valued object. Yet judgements can only be provisional, as practices continue to change with staggering rapidity.

In this chapter we will outline this complex history in which taking pictures is both a leisure pursuit and an increasingly flexible medium for the construction of ordinary people’s accounts of their lives and fantasies. In order to trace the interplay of change and continuity, the chapter will be looking at some key moments in the practice of personal photography. These include the moments of taking, organising, viewing and sharing an image, as well as searching and re-viewing – looking back at a single picture or across a collection of images. We will also consider how the history of such practices, together with the interpretive meanings we bring to the pictures, are inevitably intertwined with social, cultural and economic changes. The meanings gathered in personal collections both meet up with, and part company from, the external realities of the historical world, particularly when pictures are associated with major trauma or historical displacement.3

We have chosen to speak here of ‘private’ or ‘personal’ pictures rather than the more usual ‘family’ or ‘domestic’ pictures, because our private lives cover so much more than our family lives. The equation between ‘the family’ and private experience is too easily made and excludes too much.4 The evolution of private photography has indeed been family based but that link is historically contingent, not, as is often assumed, the consequence of ‘natural’ necessity. The story of personal photography is interwoven with a constant re-creation and subversion of what it means to be a family including single parent families, same sex partnerships and reconstituted families. In 1899 it was the picture faces of ‘old friends’ that were apostrophised in M.C. Duncan’s verse, and in the twenty-first century, camera phones are as likely to capture a night out on the town with work colleagues as baby’s first steps. The point has been made by writers such as Terry Dennett, who compare family albums to other sorts of albums that record the lives of clubs, political groups and other networks of support and obligation (Spence and Holland 1991: 72).

That private photography has become family photography is itself an indication of the domestication of everyday life and the expansion of ‘the family’ as the pivot of a century-long shift to a consumer-led, home-based econ omy. Personal photography has evolved as part of the interleaving of leisure and the domestic, whose development runs parallel to the history of photography itself.

Jo Spence And Patricia Holland (eds) (1991) Family Snaps: The Meanings of Domestic Photography, London: Virago.

In Britain and the West, the gradual expansion of domesticity from the respectable middle classes through to all but the very poorest has drawn women, children and finally even men into the ‘charmed circle of home’.5 By the twentieth century such activities as child-care, the preparation of meals and work on improving the house and garden came to be seen as pleasures rather than duties, and the nuclear family became the main resource for close rela tionships and expressive emotion. Taking snapshots joined a plethora of leisure pursuits which underpinned that specific form of family life. However, photography occupies a peculiar place among those activities, since pictures are themselves carriers of meanings and inter pretations. They record and reflect on daily activities, delicately holding within the innocent-seeming image much that is intimate and might otherwise be hidden. Here are M.C. Duncan’s ‘volumes of unwritten life’ for which we must scan beyond the edges of the frame.

Personal photographs are embedded in the lives of those who own or make use of them. Even when they are professionally taken, there is a contract between photographer and subject quite different from other types of photography. The photographs we make for ourselves are treasured less for their quality than for their context, and for the part they play in confirming and challenging the identity and history of their users.6 Personal pictures have been made specifically to portray the individual or the group to which they belong as they would wish to be seen and as they have chosen to show themselves to one another. Even so, the conventions of the group inevitably overrule the preferences of individual members. Children, especially, have very little say over how they are pictured, and this discrepancy is the source of many of the conflicting emotions analysed by writers on family photography (Kuhn 1991; Watney 1991; Walkerdine 1991). Perhaps this accounts for the excesses of some contemporary young people’s self-representations, as the more flexible technologies of the digital era appear to offer an escape from family constraints.

In this discussion it will be useful to distinguish between users and readers of personal pictures, whether family snaps, school photos or the transitory image on the camera phone.7 Users bring to the images a wealth of surrounding knowledge. Their own private pictures are part of the complex network of memories and meanings with which they make sense of their daily lives. For readers, on the other hand, a hazy snapshot or a smiling portrait from the 1950s is a mysterious text whose meanings must be teased out in an act of decoding or historical detective work. Users of personal pictures have access to the world in which they make sense; readers must translate those private meanings into a more public realm. Private photographs, taken alone, are a ‘restricted code’ in the sense described by Basil Bernstein, dependent for their specific meanings on knowledge of the rich soil of meanings that holds them in place (Bernstein 1971). Wrenched from that context, they appear thin and ephemeral, offering little in the way of either aesthetic pleasure or historical documentation. But, although such ghostly hints of other lives may tempt the reader to engage in the detective project and to construct stories from these tentative clues, the empirical historian would do well to treat them with extreme caution. The peculiar fascination of personal photographs comes from this contrast between an almost unbearable richness of potential meaning and the inconsequentiality and triviality of the medium. The theorist Roland Barthes, writing on photography and memory, could not bear to reproduce the snapshot of his recently deceased mother, even though it gave rise to his essay (Barthes 1984).

Roland Barthes (1984) Camera Lucida, London: Fontana.

Brian Coe And Paul Gates (1977) The Snapshot Photograph: The Rise of Popular Photography 1888–1939, London: Ash and Grant.

Colin Ford (1989) The Story of Popular Photography, Bradford: Century Hutchinson Ltd/National Museum of Photography, Film and Television.

Audrey Linkman And Caroline Warhurst (1982) Family Albums, Manchester: Manchester Polytechnic. A fully illustrated exhibition catalogue with an introduction.

Audrey Linkman (1993) The Victorians: Photographic Portraits, London: Tauris Parke Books.

For many years, private pictures which offer up so little to the critic and art historian, have tended to feature in histories of photography chiefly as examples of technological improvement. Historians have noted the increasing lightness of cameras, the invention of colour film and similar developments (Coe and Gates 1977; Ford 1989). Twentieth-century snapshots tended to be seen as slight and unimportant, of poor quality and of value only to those who make use of them. In recent years the arrival of the camera phone and digital media has led to a new surge of interest (see p. 179 below) but, from around the 1980s, the study of history itself began to change, and personal pictures were already being taken more seriously. A concern with local and family histories, women’s history, the history of everyday life and ‘history from below’ gave a new significance to personal pictures (Linkman and Warhurst 1982; Linkman 1993; Drake and Finnegan 1994). When scrutinised under the detective’s magnifying glass, it seems that private pictures offer up many public meanings, some superficial, some historically illumin ating. They tell us about the style of crinoline fashionable in the 1860s and about the donkeys used by beach photographers in the 1910s. They express private emotions, and they also display public ideologies – stories and ideas about how things are and how they ought to be (Isherwood 1988).

Historically, personal pictures may be deeply unreliable, yet for many it is in this very unreliability that their interest lies. It has led to a new set of questions – for whom are these pictures? who sees them? to whom do they communicate? In making an effort to reread private pictures, there has been a move to revalue the undervalued and to bring into public discourse meanings which have hitherto been concealed in the most secret parts of the private sphere. The practices of personal photography have led writers, photographers and curators (Jo Spence, Val Williams and Marianne Hirsch among them) to interpret history through private lives and autobiography. While drawing attention to the importance of this most popular of photographic practices, they have insisted that the privacy of its meanings should not be dispersed (Spence and Holland 1991; Spence 1987, 1995; Williams 1986; Hirsch 1997).

Jo Spence (1987) Putting Myself in the Picture, London: Camden Press; (1995) Cultural Sniping, London: Routledge.

Val Williams (1986) Women Photographers: The Other Observers 1900 to the Present, London: Virago.

Marianne Hirsch (1997) Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

In a parallel development, personal photography has played a different but equally important role in the modernisation of Western culture. It has developed as a medium through which individuals confirm and explore their identity, that sense of selfhood which is an indispensable feature of a modern sensibility – for in Western urban culture it is as individuals that people have come to experience themselves, independently of their role as family members or as occupying a recognised social position. The consumer-led economy of the twentieth-century shifted these new individuals away from a culture based on work and self-discipline to one based on libidinous gratification which encourages us all to identify our pleasures in order to develop and refine them. At the same time, the century of Freud became an age of inwardness and self-scrutiny. These changes are reflected in the images we produce of ourselves, the uses we make of them, and our scrutiny of the Internet for material relevant to ourselves. Scanning personal pictures has become part of that act of self-contemplation (Martin and Spence 2003; Spence 1987, 1995; Slater 1995b).

Patrizia Di Bello (2007) Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England: Ladies, Mothers and Flirts London: Ashgate

Despite the intensity of such a project, in one of those many paradoxes that makes its study so fascinating, private photography has insisted on being a non-serious practice. Cuthbert Bede, writing in 1855 in the facetiously punning style enjoyed by the mid-nineteenth century, reminded his readers that photography was ‘essentially a light subject and should be treated in a light manner’ (Bede 1855; di Bello 2007). And so it has continued over its history, seeking the playful and celebrating the trivial. Personal photography sets out to be photography without pretensions, and that is how we intend to approach it. As we trace the development of personal photography, in the spirit of other work by feminist writers on women’s culture we will not be arguing that these forms of photography should be valued as they have been used and interpreted in the galleries and by artists, but that what is needed is to understand them on their own terms.

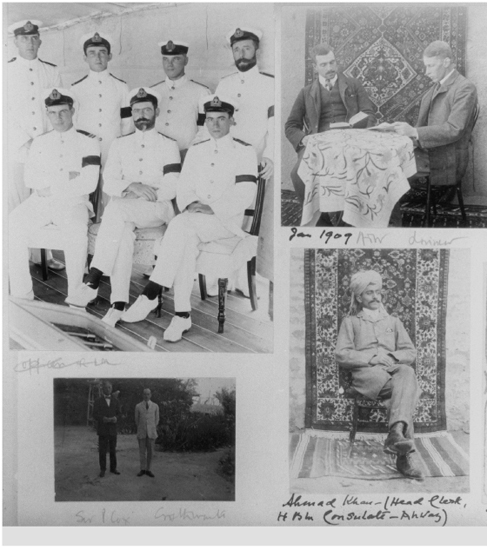

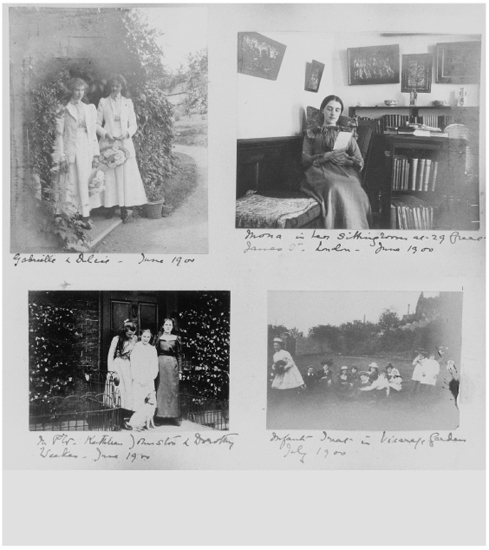

A blurring of the boundaries between public and private contexts has recently been attributed to digital practices. However, from its earliest days, personal photography has looked outwards as well as being domestically based. During the nineteenth century, images of the strange and exotic were marvels which enhanced the comfortable home and became as much part of home entertainment as television is today. In some family albums, preserved by prosperous patriarchs before the turn of the twentieth century, we can see how the middle-class home, even as it became increasingly separated from political and economic activity, depended on the world outside. Although the keeping of photographic – and other – albums was largely an activity for the women (di Bello 2007), the feminine domesticity of the extended family was visibly sustained by masculine adventure, both military and entrepreneurial.8 The copious albums preserved by Sir Arnold Wilson dramatically illustrate the point. Sir Arnold was a well-connected army officer serving in India and Persia in the early years of the twentieth century. He worked with the Anglo-Persian Oil Company in the 1920s and became a Conservative MP in the

3.2a From the album of Sir Arnold Wilson (No. 3 Persian scenes), 1909

3.2b From the album of Sir Arnold Wilson (No. 7), 1900

1930s. His family albums cover a period from 1870 to 1920, recording holiday trips, afternoons in the vicarage garden and regimental postings. Set-piece photographs of India and the Middle East are juxtaposed with gentle family groups and intimate portraits in the gardens and drawing-rooms of the family’s homes at Leighton Park Estate and in the countryside near Rochdale. In India the regimental tug-of-war team and the local Gurkha regiment present themselves proudly to the camera. In the Middle East, British officers pose one by one with local sheikhs. Tourism overlaps with colonial rule as spectacular views of the Himalayan hill station at Muree are followed by annotated pages showing the complex decoration of local mosques. In the Persian album, alongside the purchased images of silversmiths and weavers at work, Sir Arnold included pictures which claimed to be of executioners and torturers demonstrating their craft.

Discussing the colonialist imagery of advertising at the turn of the century, Anne McClintock argues that ‘the cult of domesticity became indispensable to the consolidation of British imperial identity’ (McClintock 1995: 207). The starkness of the contrast in Sir Arnold Wilson’s albums makes visible the tensions on which domestic photography has continued to be based. They look inwards at an increasingly privatised and protected domestic haven and outwards at a world of political violence, re-presented as spectacular and exotic. The pictures in Sir Arnold’s albums present this outside world with great confidence, gazing with the eyes of those who would control it and claim to civilise it. As the twentieth century progressed, and as photography became available to the ruled as well as the rulers, the politics of the world beyond the family group came to be repressed in the domestic image. The consequences of colonial domination and the ever possible presence of violence must be read beyond the limits of the frame (Hall 1991: 152). The two sides of popular photography remained, and can be traced in colonialist and postcolonialist photography (Holland and Sandon 2006; Gilroy 2007), and in the frequently shocking pictures taken by soldiers on active service (Struk 2011). However the imperial aspiration of this vision, and the celebration of commerce and military adventure of the Victorian era have long since been replaced by a tamer record of travel and tourism.

From the very early days through to the unflagging popularity of posters and postcards in the twenty-first century, popular photography has continued to include purchased pictures of unknown people and places. William Henry Fox Talbot, who first developed a negative/positive calotype process in Britain in 1839, hastened to patent his invention and turn it to financial advantage. In 1843 he set up the first printing workshop to reproduce photographs for sale. His book The Pencil of Nature was amongst the earliest to be photographically illustrated.

calotype Photographic print made by the process launched by William Henry Fox Talbot in England in 1840. It involved the exposure of sensitised paper in the camera from which, after processing, positive paper prints could be made. Not much used in England in the early days because it was protected by Fox Talbot’s own patents, but its use was developed in Scotland, especially by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson.

Within 20 years there was a thriving industry in photographic prints, which included impressive landscapes, views and still lifes. If Sir Arnold Wilson’s turn-of-the-century collection carries the confidence of those who seek to control what they see, these pictures marketed from the 1850s onwards had the more modest aim of entertainment. However, what John Urry described as ‘the tourist gaze’ (Urry 1990) itself ensures a separation between the one who does the looking, assumed to be familiar and like ‘us’, and that which is looked at, assumed to be different and strange. A taste for the exotic was already well established in the mid-nineteenth century and photography gave it a new boost. Francis Frith set up a highly profitable company which produced saleable photographs of parts of the world which up until that time had only been seen through the eyes of artists or the imaginative descriptions of travellers. From 1856 he made three expeditions to the Bible lands of the Middle East and The Times called his resulting photographs ‘the most important ever published’ (Macdonald 1979). His photographers travelled the length of the British Isles and at the height of his business his firm claimed to have one million available prints, including photographs of every city, town and beauty spot in Britain. By the later years of the nineteenth century, photographs of parts of the world, impressive because of their distance, their strangeness or the difficulty experienced in reaching them – from the high Alps to remote areas of China and Japan – were published as prints, lantern slides and stereoscopic views.

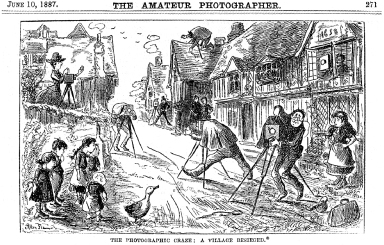

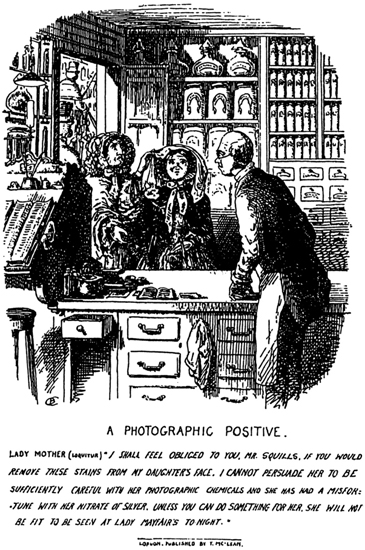

3.3 ‘The photographic craze’, Amateur Photographer, 10 June 1887

The coming of photography gave rise to a new set of dilemmas around the production of the exotic. On the one hand it displayed images of hitherto unknown and remarkable places and people, but at the same time it had to be recognised that these were real places and people. The veneer of exoticism may be confirmed or challenged by the photograph itself. We should not forget that photography was also developing in those very places that seemed exotic to the untravelled British. By the end of the nineteenth century in China, Japan and India, local photographers were making pictures for local use (Falconer 2001). Pictures which would be seen as exotica in the metropolitan West are someone else’s family photos (Kalogeraki 1991).

Popular photography has rarely been a medium of record. Foreign views exaggerated the exotic and the strange, and a fashion developed for the quaint and the traditional (for example, George Washington Wilson’s pictures of gnarled old Scottish fishermen and other local types). With hindsight this fashion can be seen as the beginnings of a heritage industry in which the imagery was threaded through with nostalgia partly brought about by photography itself, already capturing a disappearing past. Groups such as the Society for Photographing Relics of Old London set up in 1875 contributed to an archive of the past which helped to construct a tourist view of the world (Taylor 1994).

John Taylor (1994) A Dream of England: Landscape, Photography and the Tourist’s Imagination, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Middle-class artistic travellers came to deplore ‘vulgar’ sightseers, who, they claimed, ruined the very views they had come to discover. But from the turn of the century, a new generation of tourists took their cameras in search of scenic beauties previously seen only on postcards and in travelogues. At first they went by train or bicycle, but by the 1920s many were travelling by car. In the United States the publicity-conscious Kodak company pointed out scenic views with road signs reading ‘Picture ahead! Kodak as you go!’ (West 2000: 65). With each wave of visitors the possibility of an undiscovered rural scene or an unspoilt village seemed ever more elusive. A photograph was a nostalgic compensation for the loss of a world that appeared to be uncorrupted by industry and urbanisation. The heritage industry and the tourist trade between them had provided renovated antique buildings and tidied up picturesque views to create ready-made photo oppor tunit ies. Taking a picture is an intrinsic part of the tourist experi ence and ‘places of interest’ dominate the albums of many a modest traveller just as they did those of Sir Arnold Wilson – although today millions of pictures are captured on digital cameras and camera phones and instantly e-mailed to friends or posted on Facebook or Flickr for a wider audience (Urry and Larsen 2011).

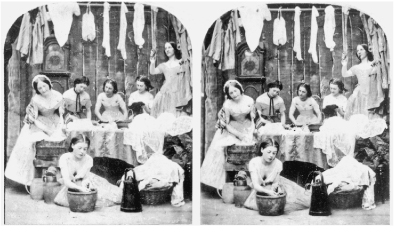

Fiction and fantasy have long been more attractive than the mundanities of everyday life, and this was certainly true of one of the most popular of nineteenth-century domestic media, the stereoscopic view. From 1854 the London Stereoscopic Company produced double pictures which gave a 3D effect when peered at through a binocular viewer. This could be a small hand-held affair or a grand piece of drawing-room furniture. By 1858 there were 100,000 different views on offer and the company’s slogan was ‘No home without a stereoscope’.

3.4 Stereoscopic slide from the late nineteenth century

Many stereoscopic scenes exploited the Victorians’ love of theatrical tableaux and aimed for a style and subject-matter suited to the taste of their middle-brow purchasers. Such ‘stereoscopic trash’ outraged the proponents of photography as art (see ch. 6, pp. 268–71). The Photo graphic Society (later to become Royal), founded in 1853 to protect artistic standards, deplored the debasement of the medium. In 1858 its journal fumed,

To see that noble instrument prostituted as it is by those sentimental ‘Weddings’, ‘Christenings’, ‘Distressed Seamstresses’, ‘Crinolines’ and ‘Ghosts’ is enough to disgust anyone of refined taste. We are sorry to say that recently some slides have been published which are, to say the least, questionable in point of view of delicacy.

(Macdonald 1979)

daguerreotype Photographic image made by the process launched by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre in France in 1839. It is a positive image on a metal plate with a mirror-like silvered surface, characterised by very fine detail. Each one is unique and fragile and needs to be protected by a padded case. It became the dominant portrait mode for the first decades of photography, especially in the United States.

Sentiment, jokes, horror, melodrama and material which verged on pornography – this was the stuff of nineteenth-century photographic entertainment. Some stereoscopes even came with a locked drawer for a gentleman to keep his risqué pictures away from his family (see ch. 4, p. 177 on the reputation of laundresses as sexually loose women). In those days before the cinema, magic lantern shows were also popular. Impressive views could be watched in a darkened room, enhanced by exciting optical effects – from a sunset over the Alps to lifelike thunderstorms (Chanan 1996). The making of personal portraits was part of this popular aesthetic, firmly embedded in commercial practices.

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre’s invention of positive images on silvered metal, each one unique, was, from the 1840s, the dominant format for personal portraits. Enterprising daguerreotypists learned the new skills and tried to interest customers in towns across Europe and the New World. In those very early days, sittings for 15–20 minutes in as bright a sunlight as possible led to extreme discomfort for the sitter and some fairly unflattering pictures which could be difficult to discern on the highly reflective surface. Even so, within a few years, huge numbers of people of middling income wanted their portraits taken, and ‘daguerreomania’ had taken hold. Photo graphic ‘glasshouses’ – so called because of the wide expanse of window needed to maximise daylight – were established in urban centres across Europe and the United States. In Britain, Antoine Claudet had a ‘temple of photography’ designed by Sir Charles Barry, who built the Houses of Parliament. In Leicester Square in London there was a ‘Panopticon of science and art’ with a room 54 feet long (approximately 16.5 metres) ‘enabling family groups of 18 persons to be taken at once’, which also offered lessons in daguerreotyping and studios for hire. Studio portraitists introduced painted backdrops so that the customers, whatever their social standing, could choose to place themselves within dignified parklands, seascapes, conservatories or palm houses. Many were extremely successful: Richard Beard was said to be photography’s first millionaire (Macdonald 1979; Tagg 1988; Ford 1989; Kenyon 1992: 11–12).

Dave Kenyon (1992) Inside Amateur Photography, London: Batsford.

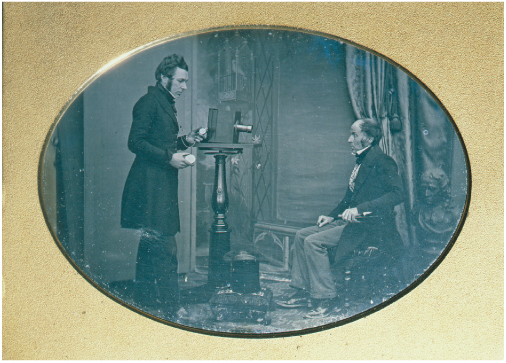

3.5 Earliest known daguerrotype of a photographer at work. Jabez Hogg photographs Mr Johnson, c. 1843

The ‘cheap and common establishments’ in the less fashionable parts of town got a bad name for aggressive touting for trade. Someone stood outside shouting, ‘Have your picture taken’, and virtually ‘dragging customers in by the collar’ (Werge 1890: 202). Most of these early portraits were carefully posed and touched up so as to produce as flattering an image as possible under difficult circumstances. A head brace could keep that most important feature, the face, static for the lengthy exposures needed. Alternatively the posing individual was asked to lean on a table or a mock-classical pillar which also served decorative and symbolic functions. The head resting on the hand achieved the popular Victorian soulful look, as well as helping the sitter to keep still. Smiles were difficult to sustain under such circumstances: the modern ubiquitous snapshot smile should be seen as a technological achievement as well as a change in social mores.

carte-de-visite A small paper print (2½–4½″) mounted on a card with the photographer’s details on the reverse. This way of producing photographs for sale was developed by André-Adolphe Disdéri in France in 1854. Eight or more images were made on the same glass negative by a special camera with several lenses and a moving plate-holder. The prints were then cut up to size. Such prints could be produced in very large numbers.

Every innovation was hailed as spreading photography more widely across the classes. ‘Such portraits are to be found in everybody’s hands’, wrote André-Adolphe Disdéri, who invented the ‘carte-de-visite’ in 1854 (Lemagny and Rouille 1987: 38). Named after the leisured classes’ ‘visiting cards’, these were small paper prints mounted on the photographer’s own decorated card. Several poses could be produced on a single negative so that the process was speeded up and multiple copies were easily available. This was the first attempt at a form of mass production of popular photographs, and certainly class differences were far less visible in such pictures than they were in everyday life. Shopkeepers, minor officials and small traders all took themselves and their children to pose stiffly in their best clothes in front of one of these early cameras.

A craze for collecting cartes-de-visite of the famous developed. Some of the earliest photographic albums were not ‘family albums’ at all, but handsomely bound volumes filled with pictures of royalty, celebrities and politicians. As pressure increased on middle-class women to make their lives within the confines of the home environment, useless but suitably decorative hobbies such as collecting cartes-de-visite fitted in well with other genteel activities such as sketching and pressing flowers (Davidoff and Hall 1976; Warner 1990; Swingler 2000; di Bello 2007).

Queen Victoria’s family was presented as a model of the new respectable domesticity, but published photographs of the Royal Family remained strictly formal. When the celebrated photographer Roger Fenton was invited to photograph the Queen’s children dressing up and presenting tableaux, the pictures were felt to lack dignity and were never released to the public (Hannavy 1975). Even so, it was the more relaxed picture of Princess Alexandra giving her daughter Louise a piggyback that became the best-selling carte-de-visite. Among their many hobbies and pastimes, women members of the Royal Family took up photography themselves, and Queen Victoria’s and later Queen Alexandra’s own copious albums were filled with views of family picnics and hunting parties (Williams 1986: 75).

3.6 A page from the album of R. Foley Onslow, c. 1860

Home photography was not for public display, but for fun with friends. In 1855 Cuthbert Bede described, for the benefit of ‘all the light-hearted friends of light painting’, many such social activities, including ‘visiting country houses and calotyping all the eligible daughters’ (Bede 1855: 44). The light-hearted uses of photographs, part of the Victorian fascination for fads and fancies, included mounting dainty miniatures into brooches and lockets, decorating jewel cases, or even setting them into the spines of a fan (di Bello 2007). A Victorian album was itself a series of visual novelties, with the portraits often cut up and arranged in decorative shapes and incorporating drawings and other scrapbook items. Mary Queen of Scots going to her execution was a favourite. And there were the mottoes: ‘Love me, love my dog’ heads a page of pets squatting smugly on their cushions. The interest is not just in the individual pictures but in the arrangement as a decorative collection (Smith 1998: 57).9

The family-based albums of the nineteenth century are those of prosperous dynasties whose members had both the leisure and the money to take up photography, as well as to buy commercially produced pictures. The life of the Helm family, in their spacious mansion in Walthamstow, elegantly photographed by James Helm and preserved in a set of albums put together in the early 1860s, demonstrates not so much the luxury and overt enjoyment of a free-spending leisure class, but the decency and quiet respectability of the middle-class suburb (Cunningham in Thompson 1990). The group is large and diverse, with aunts and other relatives and friends as regular members, in striking contrast to today’s pictures of tight-knit families in which parents and young children predominate. The leisurely lifestyle included croquet on the lawn, amateur dramatics, young men posing with their musical instruments and dignified ladies in layered crinolines taking tea. These are scenes from everyday life, carefully organised and staged in the tableau manner. In the 1840s, Fox Talbot had written, ‘when a group of persons has been artistically arranged and trained by a little practice to maintain an absolute immobility for a few seconds of time, many delightful pictures are easily obtained. I have observed that family groups are especial favourites’ (Ford 1989). The tableau was a pleasing artistic picture as much as a family record. Pictures such as these were marking out the evolving domestic sensibility of the nineteenth century, which made the home environment the centre of decent living. It was a model which the lower-middle and working classes were to emulate in the coming century.

If the home was becoming a site of leisure, the creation of the ‘hobbyist’, and its more elevated relative the ‘amateur’, meant that leisure time could be used both for scientific experiment and the creation of works of art. Although one aspect of the evolution of domesticity meant that ‘the feminine ideal was to be weak and childlike’ (Davidoff in Thompson 1990: 84), women could become home-based hobbyists. ‘Photography is the science for amateurs, equally adapted for ladies and gentlemen, which cannot be said of the generality of sciences’, wrote Bede. Among the most celebrated photographers of the nineteenth century were comfortably off women with plenty of leisure and

3.7 Illustration from Cuthbert Bede, Photographic Pleasures, 1855

domestic help, who made use of their family and immediate surroundings as raw material for their photographic works, rather than as family record. Julia Margaret Cameron’s misty portraits and visions of cupids and angels embraced and transcended Victorian sentimentality (ch. 6, pp. 298–9). Working-class women were needed as servants and helpers to service the middle-class domestic haven. Indeed, Julia Margaret Cameron’s own favourite model was her assistant and maid, Mary Hillier (Mavor 1996). There were women working as portraitists, too. John Werge remembers a ‘Miss Wigley from London’ who came to his home town in the North of England to practise daguerreotyping as early as the mid-1840s (Werge 1890).

The repertoire of personal imagery was changing. There had been an elegiac tone to much Victorian personal photography, evoked by the solemnity of middle-class portraiture and by the awareness that so many died young. Death was a central part of family life, and memorial pictures of the dead and dying were common. Babies who had died were dressed in their best and photographed in their mother’s arms (Williams 1994; West 2000; ch. 4, p. 191). But by the end of the century the emphasis was changing to a more present celebration of life and a taste for informality.

Photographic portraits had long been valued not only for their likeness to the sitter but also for the apparent escape from convention and the greater naturalness offered by the mechanical process. Bede had written that a calotype is a step beyond a painted portrait, for a painting has ‘the artist’s conventional face, his conventional attitude, his conventional background’ (Bede 1855: 45). In 1899 Richard Penlake advised amateur photographers how to avoid ‘perfect’ pictures like those of a celebrity, who is so carefully made up and posed as to seem like a wax model, or of royalty, in which the very best pose is selected from many exposures and even then ‘so worked up that scarcely a single part of the original negative prints at all’ (Penlake 1899: 16).

montage or photomontage The use of two or more originals, perhaps also including written text, to make a combined image. A montaged image may be imaginative, artistic, comic or deliberately satirical.

Penlake also offered advice on tricks and optical effects, such as making double images – so that the sitter magically appears twice in the same picture – and montaging photographed heads on to caricatured bodies: techniques which would come back into fashion a century later with the easy manipulability of digital photography. However, in the late 1800s, with the coming of hand-held cameras such conceits were on the way out. Albums of the 1880s, compared with those of the 1860s, show a much more relaxed style and closeness to the subjects. The movement and visual interest was now in the picture itself rather than in the decoration and arrangement of the pictures on the page. On one page in Sir Arnold Wilson’s album, girls and boys in sailor suits and boaters are trying out a bicycle. They are ‘captured’ with their backs to the viewer, in mid-conversation with each other, pointing their own hand-held cameras and playing up to the photographer, in a sequence of images which have much in common with the new ‘candid’ work by professional photographers such as Paul Martin and Frank Meadow Sutcliffe. At the time ‘detective cameras’ were all the rage. They were tiny, unobtrusive or concealed so that pictures could be taken without the knowledge of the subject. There was a growing taste for a different sort of personal picture, one where the contract between photographer and subject is brought into question. Secret observation was not always welcome to the observed. One local paper wrote in 1893:

Several decent young men are forming themselves into a Vigilance Association with the purpose of thrashing cads with cameras who go around seaside places taking pictures of ladies emerging from the deep in the mournful garments peculiar to the British female bather … I wish the new society stout cudgels and much success.

(Coe and Gates 1977: 18)

From the mid-nineteenth century in Britain and the USA the middle classes began to move away from the city centres to the newly built suburbs. Behind their privet hedges they were able to protect themselves from the grime of industry and the potential immorality of the streets. But the working classes remained confined to the inner cities, in areas that were filthy and un hygienic. Their homes were not places of pleasurable relaxation and they could rarely afford the cost of representing themselves through photography. We twenty-first-century seekers for the past may look at the family of Sir Arnold Wilson and see its members as they would like to be seen, but the image of the working classes which we have inherited has been produced either by those, like Oscar Rejlander, who aestheticised and sentimentalised it, or those, like Thomas Annan, who documented it for the benefit of various official projects. A sense of working-class identity is largely absent. Middle-class concern frequently took the form of outrage at the state of the less salubrious areas, often describing the people who lived there as distasteful, smelly and un healthy like their dwellings. Photographer Willie Swift, who published Leeds Slumdom in 1897, turned his pictures into lantern slides and ‘with the help of my daughters who sang suitable solos for us, we went up and down showing the dark places of the city, helping to create that healthy public opinion which eventually demanded clearance of the places shown’ (Tagg 1988: 225). In New York city, the photographer Jacob Riis was spectacularly successful, both with his dramatic photographs of slum dwellings, and his successful campaign for the demolition of ‘these sewers’. The area that was Mulberry Bend is now Jacob Riis Park (Tagg 1988: 152; see ch. 2, pp. 96–7).

Against this background, middle-class intervention became the context for another kind of personal photograph, often valued by those it represents although not necessarily made for their sake. Following the Education Acts of 1870 and 1893, which introduced universal schooling in England and Wales, some of the earliest photographs kept by working-class families are those depicting their children ranked behind wooden desks. In 1891 and 1893 respectively, the Church Lads’ Brigade and the Boys’ Brigade were launched to tidy up disorderly youngsters and get them off the streets. Photographs of clubs and bands present a disciplined image, modelled on those produced by the likes of Arnold Wilson and his regiment out in the hill stations of Muree.

3.8 Pupils at St Mary’s School, Moss Lane, Manchester, c. 1910

polaroid The Polaroid Land camera, producing instant black and white positives, was first marketed in 1947, but produced poor-quality images. Polaroid instant colour prints and slides were launched in 1963, and production was terminated in 2008.

tintype or ferrotype Tintypes, instant positive images on enamelled iron plates, were produced from 1852 to around 1946. As one of the cheapest methods, they were especially favoured by seaside photographers.

However, the shortening of the working week and the coming of the Saturday day off led to new sporting and leisure activities, which working-class people could organise for themselves and which they were beginning to record for their own pleasure (West 2000: ch. 2, on the links between Kodak marketing and leisure, especially in the USA). Modest photographs from the 1890s onwards show the cycling group, the football supporters and, above all, the trip to the seaside, made possible by the expanding railway network. Opportunist photographers were now on hand for trippers who wanted their picture taken. Long before the polaroid, the tintype (or ferrotype) could produce an instant metal positive showing little boys with buckets and spades, toddlers perched on the photographer’s donkey, and young women holding up their voluminous skirts as they paddle in the shallows. Photographers

3.9 Holiday postcard from a Blackpool studio, 1910

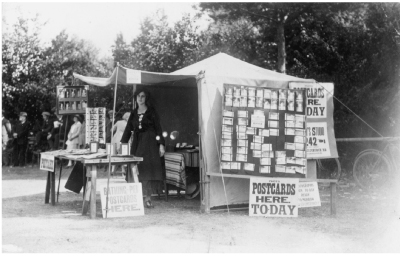

3.10 Mobile sales tent for Bailey’s photographers, Bournemouth, c. 1910

working in the new postcard format were ready with cheeky devices: ‘The subject’s head would join a monstrously fat body holding countless bottles of beer, or he would sit in a wooden aeroplane among painted stars’ (Parr and Stasiak 1986: 13).

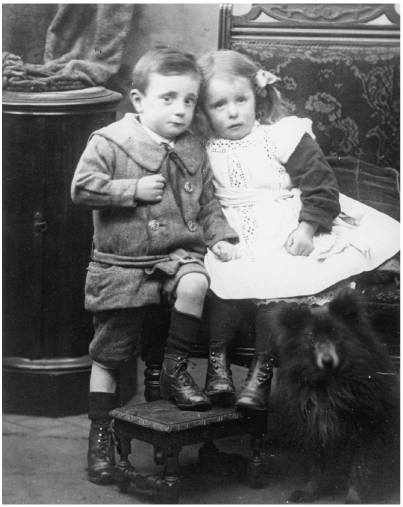

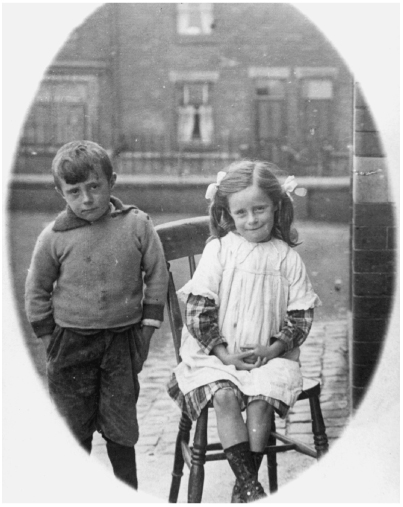

3.11 Studio photograph of Edward and May Bond, c. 1910

Not surprisingly, many of the poorer people continued to choose studio portraits where dignified or exotic backdrops would remove them from their poky homes. However, when the travelling photographer came by to set up his equipment in a local street, all the children of the neighbourhood ran after him to get in the picture. ‘Do not take too much notice of how they are taken’, wrote Edward and May Bond’s mother when she sent such a picture to her eldest son, ‘for they look a bit untidy but I did not know they were having their likenesses taken, but I thought I would buy one to let you have a look at their dear little faces’ (Figures 3.11 and 3.12).

3.12 Edward and May Bond taken by a street photographer outside their home in Manchester, c. 1912

By 1910 postcard sales were averaging 860 million per year (Pryce 1994: 143). As well as the usual repertoire of views, royalty, celebrities and tableaux, travelling photographers would set up their stall at a fair or a local beauty spot and offer to put your picture on a postcard. When people couldn’t afford the threepence (1.5p) or so for a picture, clubs were set up to pay in instalments. These jobbing photographers came from a class background similar to those whom they served. Photography was fast becoming a medium in which working-class people could present themselves to each other, creating a confident working-class identity.

3.13 Black Country chain-makers, postcard, 7 August 1911

Enterprising postcard photographers would visit local collieries, docks or mills, often producing the only photographic record of such workplaces that exist. Others specialised in local events, such as strikes, lockouts or disasters. In 1910, John Leach, a Whitehaven photographer, put together a montage of 124 of those killed in an appalling explosion and fire in the Wellington pit, as a memorial for the traumatised local community (Hiley 1983). Pictures of festivities were especially important to local people. At the Manchester Whit Walks, ‘the working class was on display and they knew it’ (Linkman and Warhurst 1982). Children who were untidy or had no clean clothes were kept well out of sight by their parents, and such pictures gave a very different impression of life in the inner city from the documentarist’s view of picturesque misery. Photographs made for the benefit of the photographer, whether as artist or concerned reporter, stand in striking contrast to those made for the eyes of the people whom they represent.

It was not until George Eastman, an American photographic plate manufacturer, successfully produced sensitised paper in 1884, and followed it up with his hand-held camera in 1888, that the paraphernalia of tripods and glass plates could finally be put aside and home photography for all became a possibility. The Kodak path was launched. Eastman was an entrepreneur with a flair for publicity, who sought to dominate the world market with a camera simple enough to be used by anyone. His crucial move was the separation of the taking of an image from the other stages involved in making a photograph. The smelly and difficult business of processing and printing was placed, conveniently out of sight, in a factory. This leisure activity for the home was supported by mass production and an army of employees – mostly women. Hence, in a single gesture, photography was both domesticated and industrialised. The first celebrated Kodak camera was a lumpish wooden box with a hole at one end for the lens. When all the exposures had been made, and they amounted to about a hundred on a single film, the whole thing was sent back to the Eastman factory for processing and reloading. The slogan ‘You press the button, we do the rest’ was to form the basis of personal photography for the following century (West 2000).

Don Slater has argued that this drastic simplification amounted to depriving the new users of photography both of skills they might have put to more radical effect and a practical understanding of how photography creates meanings: ‘Being separated from a knowledge of process, we have no sense of photography as manipulation, as a form of action, as a making sense through the manipulation of tools of representation and meaning’ (Slater 1991: 54). However, looking back with the hindsight of the twenty-first century, it is clear that such an analysis underestimates the scale in which a new skill was introduced at the end of the nineteenth. Selecting, framing and achieving the content of a photographic image was now a possibility for those who did not have the time, the money nor the inclination to engage in the complex pro cesses of amateur photography. Don Slater’s arguments also disregard Cuthbert Bede’s reminder that personal photography is a light art. Photographic manipulation had long been part of the games people played with their cameras. Producing joke pictures and clowning in front of the lens are activities which have turned taking pictures into a pastime that secures friendship and insists on interaction between photographer and subject. This is collaboration in ‘manipulating the tools of representation and meaning’, even when it’s just for fun.

The more individualist activities that the full photographic process demanded became part of a separate movement known as ‘amateur photog raphy’. The population in general, with little distinction of sex or even age, had become regular snapshooters, whereas amateur photography remained a more masculine pastime, scornful of the snapshot’s cheery refusal to concern itself with the complexities of the medium. Serious amateur practice retained its fascination with established technology and its striving for aesthetic control. It launched its own magazines, established competitions and standards. Today these have been replaced by numerous websites, open to all comers, in which the specialist status previously claimed by the serious amateur can be challenged by those happy to compete for the award for the best ‘urban wildlife’, ‘vanishing culture’ or any number of other categories.

Meanwhile, George Eastman’s commercial operations rapidly reached from Rochester, New York State to Harrow in Middlesex, and across the world. Developments followed each other in quick succession. Daylight loading, where the celluloid film came in light-tight cartons, was an advance that meant there was no longer a need to send the whole camera back to the factory. ‘Anybody can use it. Everybody will use it’ ran the publicity, listing some of those possible users:

Travellers and tourists: Use it to obtain a picturesque diary of their travels…. Bicyclists and boating men: Can carry it where a larger camera would be too burdensome…. Ocean travellers: Use it to photograph their fellow passengers on the steamship deck…. Sportsmen and camping parties: Use it to recall pleasant times spent in camp and wilderness … and Lovers of fine animals: use it to photograph their pets.

(Coe and Gates 1977: 18)

Contrary to many accounts, the first theme was looking outwards. Novice photographers were encouraged to make the most of expanding facilities for travelling – whether by ocean liner or bicycle – and point their cameras at the picturesque and the unusual. Kodak even encouraged soldiers to take their cameras to the front when war was declared in 1914 -even though this was strictly forbidden by the authorities (Struck 2011: ch. 2).

By contrast, looking inwards towards the domestic and creating an exclusive record of your family became an increasingly important message, directed largely at the women of the middle classes. This new technology was gendered. The advertising implied that its simplicity of operation meant that the woman of the house could use it, while the chemicals and other technical paraphernalia could be left to the men. And what activity could be more suitable for a woman than to photograph her children. ‘Do you think baby will be quiet long enough to take her picture mama?’ asks a cartoon-style advertisement from 1889, as a mother lines up her camera on her toddler and replies, ‘The Kodak will catch her whether she moves or not. It is as quick as a wink.’ The prosperity of those late decades of the nineteenth century had brought women a new sense of independence. The passive ‘angel in the house’ was being superseded by the ‘new woman’, and those who took up their cameras were not just housebound mothers. ‘Thousands of Birmingham girls are scattered about the holiday resorts of Britain this month, and a very large percentage of them are armed with cameras’, wrote Photographic News in September 1905. ‘It is as much a feminine as a masculine hobby these days, perhaps more so’ (Coe and Gates 1977: 28).

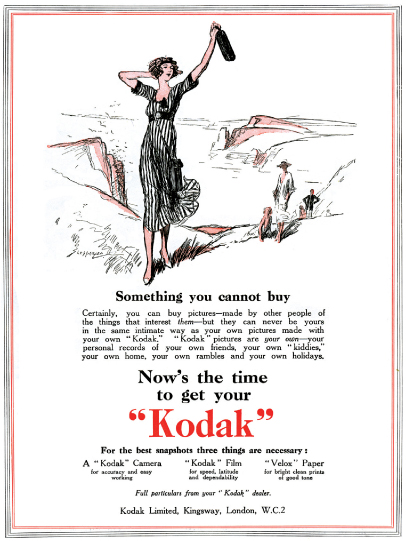

3.14 Kodak advertisement, 1926

Kodak advertisements overwhelmingly showed women carrying the camera, very often out together with other women (West 2000: 53). The ‘Kodak girl’ was introduced in 1893 – as an independent, stylish and youthful amateur who would typify the new brand. In 1910 she gained her smart but comfortable blue and white striped dress, easily adapted to changing fashions in skirt length and outline, which always seemed to be blowing in some breeze or other. Variously drawn by a number of well-known artists, she balanced her camera casually in her hand in Kodak advertisements for nearly 80 years. Always out of doors, she may be perched on a rock pointing out to sea, leaning on a jetty watching the yachts come in, or celebrating the Paris World Fair in 1934. She may be picturing children romping on the beach, or a rustic cottage, or a modern young woman in a car, while urging purchasers to ‘Make Kodak snapshots of every happy scene’ (Figure 3.14). As time went on, even the cameras were feminised. In the late 1920s, Kodaks were produced in fashion colours – pinks, blues and greens – and ‘Vanity Kodaks’ came with a matching lipstick, mirror and compact holder.

The ‘Box Brownie’, launched in 1900, cost five shillings, a quarter of an average week’s wages, which brought it into the reach of all but the poorest.10 Now the advertisements were directed at children, too. The Brownie was a camera for little folk and could, the advertisements claimed, ‘be operated by any school boy or girl’. Like the other Kodaks, it was not only easy to use but was guaranteed to be successful. However inept the operator, its pictures will always come out. Brownie albums were provided, with spaces ready prepared for slotting in a sequence of the snapshots (Figure 3.15).

Photography was not the only medium to shift from small-scale craft production to industrial production for a mass market in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Universal literacy, new printing techniques and the entrepreneurial ambitions of such men as Northcliffe and Rothermere meant that popular newspapers were launched for an unprecedentedly large readership. The advertising industry was rapidly expanding, and the mass production of all sorts of goods for domestic consumption required wider and more innovative marketing. Photography was at the centre of these developments and was to become the heart of the intensely visual popular culture of the twentieth century (see ch. 5 on photography and commodity culture). After the Daily Illustrated Mirror (today’s Daily Mirror) was launched in 1903 as the first British newspaper to use photographic illustrations, the popular press came to depend on photography as an indispensable part of news reporting, and even more importantly, as central to its entertainment role (Holland 1997). Pictures of celebrities and royalty, which in the mid-nineteenth century had found their way into carte-de-visite albums, were now to be found in newspapers and later in the burgeoning consumer magazines. Val Williams has described the relaxed pictures of the little Princesses, Margaret and Elizabeth, taken in the 1930s, as a studied model to which the whole nation could aspire (Williams 1986: 72). From the latter half of the twentieth century, the coming of high-quality full-colour printing, first in magazines, then in newspapers, meant that a huge range of topics – fashion, gardening, cookery, travel and tourism, entertainment, celebrities and music – became part of a light-hearted and pleasurable lifestyle created by high-quality photographic imagery. Over the years, this commercial and popular photog raphy would exert a significant influence on personal photographic styles, promoting ideas and aspirations as well as commodities.

3.15 A page from a Kodak ‘Brownie’ album, c. 1900

In the early years of the twentieth century the new domestic photographers had fewer models to imitate. But, as life improved for the less well-off, the working classes were beginning to follow the familial ideal established – and indeed enforced – by the Victorian middle classes (Davidoff in Thompson 1990: 106). As the lifestyles of the different classes grew closer together, the snapshot came to influence a casual and informal mode which gave a democratic veneer to social divisions. Yet, the poorer the community, the less directly their daily activities are reflected in the pictures they keep. Those who lived in the inner city tenements remained anxious to record the formality and dignity of their life, not its more distressing moments.

With the coming of the First World War there was a boom in camera sales, which reached its peak in 1917 as families bought cameras to record soldiers leaving for the war (Coe and Gates 1977: 34). Portraits of young men in uniform, many of whom never returned, made a poignant moment in most twentieth-century family collections. However, the increase in working-class incomes paradoxically brought about by the war meant that, by 1916, the Kodak Trade Circular could advise retailers that:

the people of the working class could be looked on as a likely buyer … it may even be said that they are better able to appreciate the Kodak than some of the people who usually buy it. The craftsman who works a high speed tool and who has to work to very fine measurements is just the right type of man to admire the mechanical excellence of the Kodak…. If your shop is near a working class neighbourhood, think this over.

(Coe 1989: 69)

Following the two major wars of the twentieth century, each of which created unprecedented social upheavals, ‘the family’ was reasserted as a force for reconstruction and social cohesion. During the Second World War, for a brief period, popular photography had included high-quality photojournalism developed by Picture Post, which concerned itself with the ‘home front’, public life and communal responsibility, as well as with military campaigns; but in the postwar period, just as in the years following the First World War, a reconstructed economy was based on domestic consumption and the domestic ideal. This required, in particular, women’s willing return to the home to become the pivot of family life, relinquishing their public presence in the workplace and revaluing the ideal of a private sphere where political forces appear irrelevant. Twentieth-century family photography, with its resolute insistence on the creation of happy memories, determinedly reflected this mood, in which politics and world affairs, even the most disruptive, are pushed to the background of public consciousness (Taylor 1994: 141).

Despite the Depression, it was during the inter-war years of the 1920s and 1930s that a home-based family idyll took hold in the mock Tudor, semi-detached suburbs of English towns. Here the rising working class found for the first time ‘such homes of which thousands have only dreamed’ (Holland 1991). The stiff front parlour became a living room designed for leisure use and rigid gender and age divisions gave way to companionate marriage and demonstrative parenting (Davidoff in Thompson 1990: 116). The domestic ideal, built up over the nineteenth century as a space that would be calmer and morally superior to the turbulent world outside, was being narrowed down to a much smaller family, made up of two parents and their younger children, who aimed to lead a pleasurable rather than dutiful life. A state of mind was coming about in which the satisfaction of each individual’s desire for comfort and satisfaction would not seem incompatible with the mutual obligations demanded by family groups. The increasing relaxation and informality appearing in family snapshots echoed that change.

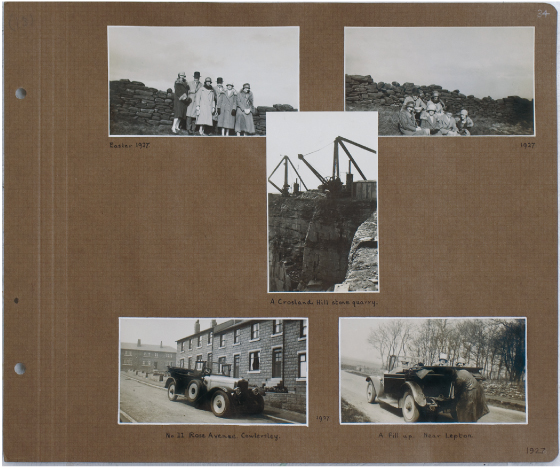

3.16 A page from the album of Frank Lockwood, 1927

Frank Lockwood was a Birmingham watercolourist and designer for Cadbury Brothers.

The image of the child became the central icon of family life. By the 1930s the two- or three-child family was the norm, which meant that individual attention could be given to each child and there was more time for birthday celebrations, Christmas trees and the snapshots which accompany these ceremonies. The domestic camera was confirmed as a ritualised element in joint celebrations (Musello 1979). As well as the visible markers for home-centred values, children signified the aspirational optimism of a century dominated by the newly prosperous working and lower-middle classes, whose horizons seemed to be ever widening. The modest pictures of the period between the wars give off a sense of hope, a belief in progress and in the possibility of a comfortable life for all.

Despite the ideology of ‘home’ as a warm, familial centre, most collections of personal pictures are, in fact, dominated by time spent away from the home. As well as becoming closer and more inward-looking, the family was also becoming mobile (Slater 1995b: 132). The gradual spread of motor-car ownership meant that holidays and days out could be more private, enjoyed by the couple or the young family instead of the noisy, gregarious group. The domestication of the unfamiliar, by capturing it on film, has remained one of the most important uses of snapshot cameras since Kodak’s first appeal to tourists and travellers. A site is not a sight until we’ve snapped it and made it ours, often by placing a familiar face – whether travelling companion or family member – in an unfamiliar place. Many of Kodak’s early advertisements addressed themselves to those who set out in search of the impressive and the educational, but these adult activities take second place to trips and holidays which have become an indispensable element of family pleasures. The centre of Kodak’s advertising, from the Kodak girl on the windswept British beach to the sun-saturated images from the Costa del Sol, has been the child-centred family holiday.

In the second half of the twentieth century, increasing prosperity, together with the introduction of package tours and the establishment of an energetic tourist industry, meant that overseas holidays were to become the norm. But, while personal collections became filled with photos of Mum, Dad and the kids in ever more distant locations, pictures of home-based daily life emerged in commercial imagery. The expansion of packaged foods and branded goods brought new outlets for visual images which showed what a happily consuming family should be like. Commercial photographers studied how to create ever more convincing pictures of appetising food consumed by ecstatic and grateful youngsters and of well-groomed mothers delighting in their newly technologised kitchens. Such images, perfected for advertisements and promotional design, were routinely delivered to the breakfast table on cornflakes packages and baby food jars, and greeted shoppers with their serried ranks on the shelves of the early supermarkets. The 1960s burst into commercial colour as the burgeoning products for domestic use were promoted by advertising-based supplements to the Sunday papers and an expanding range of consumer magazines which drew on the new, high-quality colour printing techniques (Crawley 1989). The lush photography on their feature pages came to cover every aspect of domestic life – from Home and Garden to Mother and Baby (Holland 1992). Snapshots and consumer imagery were fast becoming two sides of the same coin.

In 1963 Kodak produced ‘a complete new system of snapshot photography’ when it brought out its ‘Instamatic’ series of small reliable cameras (Ford 1989: 141). It was the result of ten years of research which sought to make snap-shooting even easier. Cheap colour printing and faster film stocks made it increasingly possible for home photographers to emulate the sophisticated images they were seeing all around them. Snapshot photographs now came in ‘bright, beautiful colours and subtle shades – like life’, in the words of a Kodak advertisement from 1969. Once more, women were the target purchasers. Unlike the ‘male jewellery’ of massive lenses and proliferating accessories, the ‘Instamatic’ removed the technological mystique. Cartridge loading and fixed focus made it so simple that ‘even Mum could use it’.

Advertisements encouraged a wider range of subject-matter and ever more casual and informal pictures, catching ‘the moment as it happens’. Automatic built-in flash meant that colour pictures could be taken indoors, in dull weather or in the rain. ‘Memories are made of this’, was the slogan. Through hundreds of glowing, full-colour pictures, a couple could now confidently record every precious moment, from the birth of their first baby to their grandchildren and beyond. The last quarter of the twentieth century became the age of the ‘supersnap in Kodaland’.

Those are the words of Jennifer Ransom Carter, advertising photographer for Kodak Ltd from 1970 to 1984. She produced many of those joyful images which offer themselves in advertisements and on print wallets for snapshooters to emulate. She ‘tried to get pictures which were as close as possible to those that people would have liked to take for themselves’. In Majorca she photographed holiday-makers as well as models. Promotional pictures ‘had to have a universal appeal, so that people would say “I want to take a picture like that …”. We aimed to tread a line between reality and unreality as we produced a professional interpretation of the family snap.’11 And, of course, the pictures people want to keep are those that record the ‘happy memories’, not the messy reality. It is hardly surprising that family collections include annual pictures of Christmas dinners and birthday teas, but hardly any of the daily meal or the act of peeling the potatoes or washing up. No children’s party is complete without snapshots, but crying, bullying or sulky children are definitely not for posterity.

As Leonore Davidoff has pointed out, as the family became more inward-looking, it came to contain ‘the most immediate experience of love and hate, power and dependence, interpersonal attention and interpersonal violence that most people would experience in their lifetime’ (Davidoff in Thompson 1990: 129). It was that gap between the enrichment and proliferation of ideal images of family life and the complexity of its lived reality which led to the damning critiques of the 1970s, particularly from the youthful and energetic women’s movement. Unhappy childhoods, broken families, child abuse, disgruntled teenagers and the persistence of poverty are only a few of the all too common experiences not recorded in domestic pictures. The family image came to be seen as riven with fractures and contradictions. Divided, individualised, hypocritical, it was argued that ‘the family’ itself was coming up against its limits.

Many commentators have stressed the cohesive function of family photography, but the use of snapshots to celebrate time out and time off has long meant that fun in Kodaland, seeking individual pleasures, may well be at odds with family obligations. A hint of disruption hovers nervously just below the surface of so many personal pictures – a tendency which has increased with the coming of camera phones and instant imaging. Holidays are a time for throwing off constraints, a time of sexual adventure and illicit indulgence, and in the snapshots many such moments are for ever preserved. Pictures of leisure activities increasingly included the carnivalesque – cross-dressing for the last-night party, sidling up to the Greek waiter, the work outing when everyone was impossibly drunk, the risqué nude image, the scantily clad teenage clubbers. Just as Mediterranean food and street cafés spilled back on to previously drab British streets, the holiday mood of these snapshots offered a reproach to dutiful lifestyles. Local pubs began to cover their walls with beery pictures which verged on the lewd, where skirts are raised, the wrong husbands kiss the wrong wives, and family values are playfully – and sometimes really – put to the test. With the increasing informality and emotional expressiveness of social behaviour, a hedonistic culture of clubbing and binge drinking took over the night-time streets in the 2000s. Young people using their camera phones to capture each other drunk, vomiting, taunting and even attacking each other became a new, and darker, phenomenon in the history of personal photography. Newspaper reports began to include headlines such as ‘Wine Women and photos’:

Women are posting pics of their drunken antics on Facebook…. Nearly 150,000 people have joined Facebook’s group ‘30 Reasons Girls Should Call It A Night’, which shows pictures of women caught with their pants down, collapsed on the dance floor and arm in arm with the sick bucket.

(The London Paper, 12 November 2007)

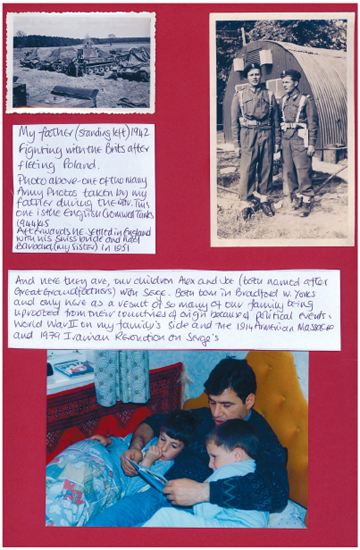

Giving an account of recent personal photography is a complex task. Nineteenth-century pictures are beyond living memory. They can be treated on their own terms – as documents, as aesthetic creations or as someone else’s story.12 Late twentieth- and twenty-first-century pictures are part of lived experience and hint at meanings which are tantalisingly within our grasp. Almost everyone has their own collection of pictures – the earlier ones may be organised in packets or drawers, some may be in albums, others scattered around in a disorderly fashion but impossible to throw away. Ever increasing numbers are digitally stored on a computer, a tablet or a camera phone. Every collection is different, every example unique. It is no longer sufficient to outline a social history of such images, since any history must include interpretations and contextual information brought by their owners and users.13 These pictures do not stand alone but are enriched by memory, conversation, anecdote and whispered scandal. They are truly personal because they are part of the accumulated history of people currently alive, who know all too well that memories are not exclusively happy ones. Above all, they include pictures of oneself as a child and at earlier periods of one’s life, pictures which carry a burden of significance that only their subjects can comprehend. It is hardly surprising that collections of such photographs hold great personal importance. In an American study of people’s ‘most cherished objects’, many respondents broke down when describing those pictures they felt they could never part with (Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton 1992: 68). Yet for writer Teshome Gabriel, a snapshot of himself as a young man, given to him by his mother when he returned to his birthplace in Ethiopia after an absence of 32 years, proved to be an ‘intolerable gift’ (Gabriel 1995). Because photography in all its forms holds the past before our eyes with unprecedented veri similitude, a sense of the recent past, including one’s own, is more vividly present to those now living than to any previous generation. Yet no photograph can give a clear and straightforward insight into the past. Personal photography, as we have seen, has a history of its own which meets up with and overlaps with social history but needs to be explored on its own terms. While many individuals bring to their personal collection the sort of emotional investment shown by those elderly Americans in the ‘cherished objects’ study, these are their responses as users of the images. To make sense of pictures which are not our own, we must change gear to become readers of the pictures and engage in a textual and semiotic exploration, paying attention to cultural as well as photographic codes. As we will see, many writers have argued that one may become a reader of one’s own pictures, too; teasing out meanings that go beyond questions of factual memory and emotional response, giving a different sort of understanding to the history they represent.

Possibly the most frequent – and most important – image in anyone’s snapshot collection is the simple shot of a subject presenting themselves to the camera, standing, perhaps in front of a famous monument or beside a car or house, but basically just being there. Yet this is the least readable of images, depending heavily on knowledge of the subject, on why the picture was taken and on its context. As Stuart Hall pointed out in relation to portraits of black Britons from the 1950s – dressed in their best and presenting themselves with great dignity – such innocence will always be deceptive, subject as it is to pressures from outside the frame (Hall 1991). The calmest portrait may offer evidence of recovery from illness or survival against the odds, and the most conventional of snaps may conceal dreadful abuse (Williams 1994: 31). Discrimination, persecution and social injustice are rarely explicit. ‘How will you understand your past when all you have is photographs?’ asks Ilan Ziv in his film about memories of the Holocaust.14

As we have seen a rereading and re-viewing of family pictures was promoted by the radical history movements of the 1970s. This brought different ways of understanding history, more sensitive to the type of information carried by everyday documents, including personal snaps. Not only academic historians, but also reminiscence groups, women’s groups and local historians, set out to challenge the politics of traditional history writing by looking at the past from a different perspective. There was a desire to write history from below, to listen to ordinary people’s accounts and to recapture the texture of ordinary lives. Those who had been hidden from history – women, black people, working-class people and many minorities – insisted on writing their own histories that ran counter to the dominant view of events, and they used personal photographs as part of the process. Arguing that women’s stories have been concealed by the conventional ways of recording history, women writers drew on personal pictures to fill those absences. Projects included getting elderly women to recall their times at work, and tracing female ancestors (Stanley 1991; Grey 1991). Radical photographic movements – Camerawork, Hackney Flashers and others – joined in a campaigning attack which took on convention, capitalism and the ideology of the family.