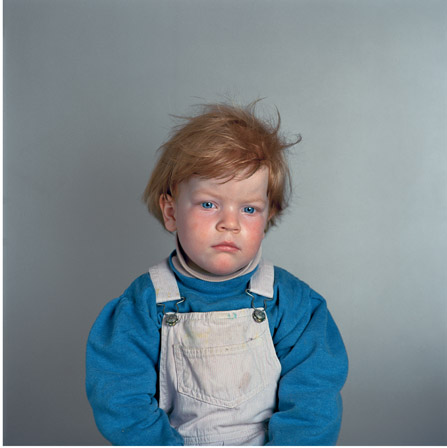

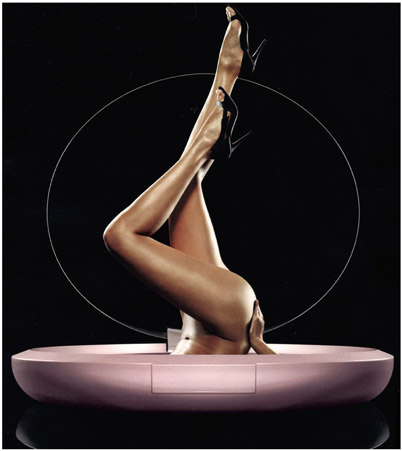

5.1 Wolfram Hahn, #1 from Disenchanted Playroom, 2006

Photography and commodity culture

Introduction: the society of the spectacle

Photographic portraiture and commodity culture

Photojournalism, glamour and the paparazzi

Stock photography, image banks and corporate media

Commodity spectacles in advertising photography

Case study: The commodification of human experience – Coca Cola Open Happiness campaign

The transfer and contestation of meaning

Hegemony in photographic representation

Photomontage: concealing social relations

The fetishisation of labour relations

The gaze and gendered representations

Case study: Tourism, fashion and ‘the Other’

Case study: Benetton, Toscani and the limits of advertising

5.1 Wolfram Hahn, #1 from Disenchanted Playroom, 2006

Photography and commodity culture

In societies dominated by modern conditions of production, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.

(Debord 1967: section 1)

In the twenty-first century, commodity relations rule our lives to such an extent that we are often unaware of them as a specific set of historical, social and economic relations which human beings have constructed. Like any cultural and technical development, the development of photography has been influenced by its social and economic context. The photograph is both a cultural tool which has been commodified as well as a tool that has been used to express commodity culture through advertisements and other marketing material. Capitalism’s exploitation of the mass media and visual imagery to create an array of spectacles and illusions that promote commodity culture can be explored by considering some of the ideas that the French Situationist Guy Debord discussed in his book Society of the Spectacle (Debord 1967).1

In this book Debord outlines the way in which modern industrial capitalist society has created a world in which the majority of people are increasingly passive and depoliticised as a society of spectacles, both media and otherwise, absorbs us into a world of illusions and false consciousness. He describes these spectacles as ‘a permanent opium war’ and discusses the way in which ‘the spectacle presents itself as a vast inaccessible reality that can never be questioned. Its sole message is: “what appears is good; what is good appears”‘. Debord’s concern is with the endless proliferation of media messages – frequently visual and usually photographic – that saturate our existence both inside and outside our homes, through billboards, television, films, magazines, newspapers, the internet, commodity packaging and ephemera. These media messages are predominantly focused on a world of glamour and entertainment where labour relations and issues of conflict (when addressed) are usually packaged around an array of feel-good factor articles and presentations to remove the sting from conflict and contradiction and to present these as a distant ‘other’ world. Debord’s key argument is that ordinary people as spectators of spectacle remain passive, uncreative and therefore powerless in the running of society. Wolfram Hahn draws our attention to the passive stupor that even children are induced into through televised spectacles (Figure 5.1). Baudriallard and other postmodernists have also recognised the impact of spectacles and media messages in the late twentieth and twenty-first century. They have described the world of spectacle as a hyperreality, as a form of representation in which mediated images appears more real than reality itself. Baudriallard argued that we live in a world of simulations where images of reality circulate through the media and impact on our understanding of the world more than lived experience. In such a world mediated messages circulate to reference other mediated messages gaining their value through their intertextuality (Baudriallard 1983; Eco 1987). Debord however highlights how the spectacle does not simply impact on our reality but is part and parcel of the entire political economy that Marx describes which creates a ‘false consciousness’ from which he believes we can free ourselves. Baudriallard denies this possibility. Douglas Kellner has recently applied Debord’s ideas to discuss media spectacles in the late twentieth century (Kellner 2003). Kellner discusses the way in which global mega-spectacles such as celebrity murder trials like that of Oscar Pistorius in South Africa are given so much space and time on television and in the rest of the mass media that these events are elevated in the minds of media consumers in the Global North to positions of greater or parallel importance to those of wars or other atrocities.2 Photographic images – both still and moving – are crucial in supporting the society of spectacle.

Cameras define reality in two ways essential to the workings of an advanced industrial society: as a spectacle (for masses) and as an object of surveillance (for rulers). The production of images also furnishes a ruling ideology. Social change is replaced by a change in images. The freedom to consume a plurality of images and goods is equated with freedom itself.

(Sontag 1979: 178–9)

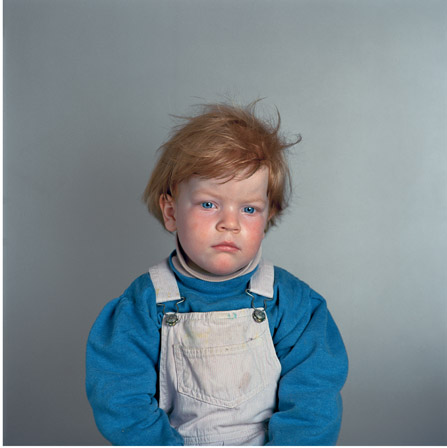

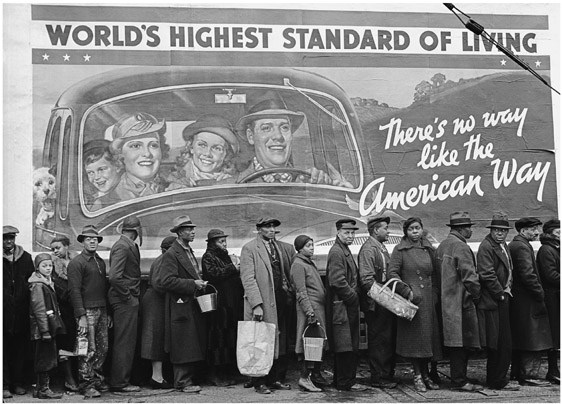

Margaret Bourke White touched on these ideas as early as 1937 in her documentary photograph, ‘The American Way’ (Figure 5.2). The image suggests the possibility of challenging false consciousness by highlighting the contradiction of lived experience.

5.2 Margaret Bourke White, The American Way, 1937

This chapter will consider examples of the photograph as a commodity and its role in promoting and representing commodity culture. It will explore the way in which capitalist ideology has impacted on forms and styles of photography which we see today and the way in which photographic use and practice is organised. This first section on the society of the spectacle concentrates on exploring examples of commercial photography which are outside of the field of advertising and marketing, the kind of photography which needs to be understood commercially but is not created to sell commodities, but to sell itself.

John Tagg (1988) ‘A Democracy of the Image: Photographic Portraiture and Commodity Production’ in The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories, London: Macmillan.

John Tagg has described the development of photography as ‘a model of capitalist growth in the nineteenth century’ (Tagg 1988: 37). The rise of commodity culture in the nineteenth century was a key influence on the way in which this technology was developed and used. The way in which photographic genres were affected by capitalism is illustrated in Tagg’s essay by the demand for photographic portraits in the nineteenth century by the rising middle and lower-middle classes, keen for objects symbolic of high social status. The photographic portraits were affordable in price, yet were reminiscent of aristocratic social ascendancy signified by ‘having one’s portrait done’. Tagg describes how the daguerreotype and later the carte-de-visite established an industry that had a vast clientele and was ruled by this clientele’s ‘taste and acceptance of the conventional devices and genres of official art’ (Tagg 1988: 50). The commodification of the photograph dulled the possible creativity of the new technology, by the desire to reproduce a set of conventions already established within painted portraiture. It was not, however, simply the perspectives and desires of the clients visiting photographic studios that encouraged the adherence to convention, but also the attempt, as McCauley has highlighted in her study of mid-nineteenth-century commercial photography in Paris, of the small business owners of these photographic studios both to establish themselves as part of a bourgeois class, as well as to assert the claim of photography as a highbrow art (McCauley 1994).

daguerreotype Photographic image made by the process launched by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre in France in 1839. It is a positive image on a metal plate with a mirror-like silvered surface, characterised by very fine detail. Each one is unique and fragile and needs to be protected by a padded case. It became the dominant portrait mode for the first decades of photography, especially in the United States. See also p. 130.

carte-de-visite A small paper print (2½–4½”) mounted on a card with the photographer’s details on the reverse. This way of producing photographs for sale was developed by André-Adolphe Disdéri in France in 1854. Eight or more images were made on the same glass negative by a special camera with several lenses and a moving plate-holder. The prints were then cut up to size. Such prints could be produced in very large numbers. See also p. 132.

Elizabeth Anne Mccauley (1994) Industrial Madness: Commercial Photography in Paris 1848–1871, New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press.

Suren Lalvani (1996) Photography, Vision, and the Production of Modern Bodies, Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Suren Lalvani has also highlighted the way in which nineteenth-century photographic portraiture was a powerful expression of bourgeois culture through the conventions of display in both dress and the arrangement of the body. Lalvani gives examples of the way in which these portraits upheld capitalist values about the nation-state, the family and the individual. ‘In bourgeois portraiture, it is especially the arrangement of heads, shoulders and hands – as if those parts of our body were our “truth”‘ that act to furnish evidence of the individual as though ‘the world may be civilized by the domestication of the hand by the head’ (Lalvani 1996: 52). Photography was not acting independently in the development of the bourgeois ideal, but borrowed from and was influenced by other disciplines such as physiognomy and phrenology (see ch. 4, pp. 173–7). Lalvani also points out the way in which these images, frequently produced for public consumption as the craze for cartes-de-visite developed, represent the development of a spectacular economy of images. He notes how political leaders of the time as well as royalty exploited the craze for collecting and exchanging the cartes-de-visite to promote their own popularity (see ch. 3, p. 132). President Lincoln, for example, is said to have believed that the carte which Brady produced of him helped him to win the presidency. Photographic portraiture in the nineteenth century therefore acts as an example of the influence of bourgeois thought both on the form and style of portraiture as well as an example of the development of ‘a regime of the spectacle’ (Lalvani 1996: 82). Today Facebook and Instagram photography continue the conventions of display that express the capitalist promotion of the individual most acutely witnessed through the development of the selfie.

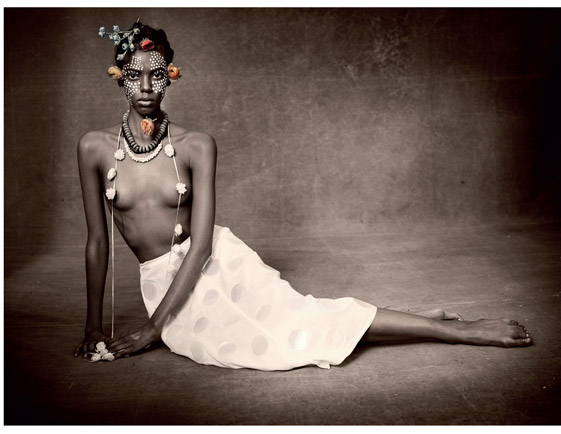

The regime of the spectacle developed in the early days of photography consolidated both racial and class-based hierarchies as they produced new forms of commodities. The cartes-de-visite acted to affirm the status of Europe’s bourgeois class through named and individual portraiture. At the same time the picture postcard marked out a colonial spectacle that consolidated a racialised regime of representation, where Africans and Asians were measured and recorded for their difference, rarely named but marked instead as exotic and subjugated types to enhance the European bourgeois’ belief in their own superiority.

Just as photographic genres have been affected by commerce, so has the development of photographic technology. The ‘Instamatic’, for instance, was clearly developed in order to expand camera use and camera ownership. In turn, this technology limited the kind of photographs people could take (Slater 1983). The camera capabilities of the mobile phone with filters to create images that adhere to established conventions of photographic practice perform a similar function.

Don Slater (1983) ‘Marketing Mass Photography’ in H. Davis and P. Walton (eds) Language, Image, Media, Oxford: Blackwell.

Matt Carlson (2009): ‘The Reality of a Fake Image: News norms, photojournalistic craft, and Brian Walski’s fabricated photograph’, Journalism Practice, 3(2): 125–139.

Another area in which we can observe the operations of spectacle is that of photojournalism. Although a documentary form of photography which has been used to highlight atrocities and deliver information and news, the photo-journalist is keenly aware of the need for spectacular images that will draw attention on the news stand and encourage sales above those of rival newspapers. In Britain and America in the 1930s, the establishment of publications such as Life and Picture Post saw the photographic image begin to command what was considered newsworthy. Dramatic and sensational images meant newsworthiness. In wars and situations of conflict photojournalists have frequently intervened to create more dramatic images. In 1937 for example, H.S. Wong placed a baby on to the railway line of the bombed-out Shanghai railway station to create an image which could captivate the despair and devastation of the Japanese bombing. More recently in 2003 Brian Walksi a photographer for the Los Angeles Times montaged two photographs, taken seconds apart, of a British soldier with a civilian crowd in Basra to create a ‘better’ image. The altered image that ran on the front cover of the Los Angeles Times, along with the two original photographs used to create it, can be viewed at http://sree.net/teaching/lateditors.html. Walski was instantly fired by the LA Times upon the discovery that he had photo-shopped the image. His actions were seen as inexcusable in a world which maintains a belief in journalism as capturing raw reality as opposed to ‘acknowledging news as a subjective cultural practice shaped by naturalized conventions’ (Carlson 2009) The pressure put on journalists to feed back dramatic images can be seen as a key reason for Walski’s action. Such drama does not always exist in life. Stories without it are ignored by the papers. On some occasions, people have used their knowledge of the newspapers’ need for photographs of high drama to get their perspective heard. With the publication in 1988 of the Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie, quiet protests by Muslim organisations against the book did not make the news. It was only when one group in Bradford, UK, provided the cameras with a dramatic image of book-burning that their voice and position was heard. Such an image of people acting as extremists is a recognised strategy for selling papers.

Although individuals have sometimes intervened in the production of the spectacle, it has been primarily produced by those with the financial clout to do so. The first Gulf War saw a major PR company, Hill & Knowlton, promote the need for war after being hired for the princely sum of $5.64 million by an organisation of 13 members (Citizens for a Free Kuwait). Their PR strategies included Kuwait Student Information days, countless press conferences and the production of documentary images that they distributed of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait and of human rights abuses there. As Mark Miller writes, ‘indeed, throughout these crucial months [September to December] there was, on TV, no other footage of or about Kuwait: every single documentary image that was telecast had been prepared by Hill & Knowlton’ (Miller 1994: 64). In the recent invasion of Iraq, Freimut Duve, the expert on media freedom for the Organisation of Security and Cooperation in Europe argued: ‘We are entering a historic phase where war is turned into a spectacle. A high percentage of people are watching without realising that it is a war’ (AFP 2003). During the first days of the war, it was presented as a real media spectacle to be followed around the clock. Viewers were led to believe that they were ‘very close’ to the action, ‘but it was in fact a form of reportage, especially on US television, that avoided the reality of war. It was extremely far away from the realities in the cities, in the region’ (Rahir 2003). In the light of such promotional practices, Walski’s montage is an inevitable practice which acknowledges the constructed and ideological nature of news discourses.

Carol Squiers (2003) Over Exposed: Essays on Contemporary Photograph, New York: The New Press.

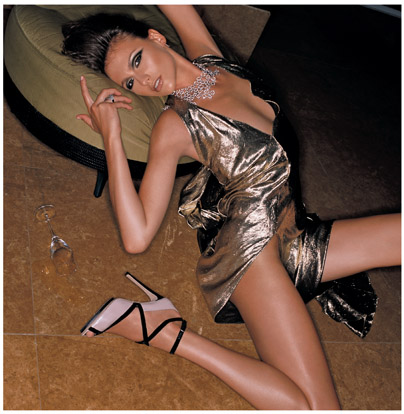

The development of the spectacle has also spawned a journalism of the sensational. The tabloid newspapers such as the Sun, Daily Star, Daily Mirror and News of the World in Britain, and the Globe, Star and Enquirer in the USA focus entirely on the production of a journalism of the spectacle which promotes and destroys stars and celebrities to provide a treadmill of stories of sex and scandal. Photographs play a major role in these stories. Two styles and forms of photography dominate this journalism: the official photographs provided by the stars and their media machines, and the ‘stolen’ paparazzi photographs that often tell a different story. Carol Squiers has discussed the photography of stars, the origins of paparazzi photography and the exploitation of the image of Princess Diana by the tabloid press. In her essay she outlines how the posed images of stars taken for editorial and advertising purposes place a high value on the stars’ ability to control and manipulate every aspect of the image – lighting, makeup, costume, hairstyle, facial expression, posture, and gesture. ‘Big stars usually demand and receive blanket control over who takes the pictures, how they will be constructed, where in a publication they will be used, and which images will be reproduced’ (Squiers 2003: 274). The effect is to construct the stars as individuals in a spectacularly perfect world, with perfect clothes, perfect hair, perfect bodies, perfect lips and perfect lives. These, usually high gloss photographs are akin to the photographic world of advertising by their creation of technically perfect images of dreams and images of desire. By contrast, the paparazzi photographs are the opposite of this. They are images of individuals caught unaware – stripped of their luxury and dazzle.

Rather than molding a celebrity as a uniquely magical creature the way posed pictures do, paparazzi images show celebrities as more mundane figures who sometimes inhabit the same space (a city sidewalk, a parking lot), perform similar tasks (shopping, jogging) and wear same clothing (blue jeans, sloppy sweaters) that the non celebrity does.

(Squiers 2003: 274)

These images are sometimes blurred and of poor quality, but this simply adds a mark of their authenticity – their ‘truth’. These photographs however, while seemingly reporting on the ‘real’ star and therefore apparently concerning itself with issues of the ‘truth’, channel the tabloid into focusing on the truth about stars as opposed to issues of the truth about how society operates. Paparazzi photography is also often a play between the celebrity and the photographer, with celebrities using photographers at particular moments to construct their image. Witness Diana’s use of photographers on an official visit to India when her marriage with Charles was failing. She visited the Taj Mahal by herself and allowed herself to be photographed alone, against a backdrop of one of the most ornate monuments to love (Squiers 2003: 300). Her image captivated the journalists and she upstaged her husband in the news coverage.

More recently Beyonce posted photographs of herself drinking a glass of wine and relaxing with her daughter to prove that she was not pregnant again. The snapshot style of photography in these posts is important in producing an image of constructed authenticity that encourages interest and belief in their ‘truth’ value. This journalism of the spectacle has no moral consciousness and is not intended to encourage the viewer/consumer to reflect on the deeper conflicts in society. It is a journalism which feeds off personalities and stars created through former media coverage – both official and paparazzi. The image of stars is carefully managed. Too plastic, sensational and consumer focused an image can also have a detrimental effect and damage public opinion. This media game is acknowledged in popular cinema. The Hunger Games trilogy is set around an understanding of media propaganda. In the second film Catching Fire, mentor Haymitch Abernathy asserts to Catniss and Peeta ‘you two are mentors now, from now on your job is to be a distraction so people forget what the real problems are’, articulating Debord’s statement ‘What is good appears, what appears is good’. The need to control the celebrity image to ensure it appears real is also commented on when Plutarch Heavensbee promises Snow that punishing ordinary citizens while putting Katniss’ wedding planning on display will serve to make her look shallow and disengaged. ‘What’s the dress going to look like? Floggings,’ Plutarch suggests. ‘What’s the cake going to be? Executions … They’re going to hate her so much, they might kill her for you.’

Celebrities and stars take care to project themselves as rounded personalities and photographic imagery is central in this orchestration. While Beyonce has signed one of the highest endorsement deals with Pepsi for $50 million which includes using her face on limited edition cans of drink and appearances in television commercials, she is also careful to keep involved in charity work to maintain her ‘A’ list status. These charity appearances are most importantly photographed to add to her carefully managed brand profile. The branding of her image has developed so extensively in 2013 that Beyonce’s charity work is no longer found on her website under www.beyonce.com/charity but instead under ‘beygood’ to match the ‘beyhive’ section of her website that acts as a more traditional celebrity blog promoting people and companies that she offers association with. The centrality of the photographic image in communicating the Beyonce brand in music, fashion and good causes can be seen by the almost complete absence of any textual discussion of issues or experience. The images are left to resonate, to mean whatever the viewer invests in them. In #Beygood, the only verbal communication is of Beyonce’s own compassion: ‘Everything I am, with everything I do I have to give back, I have to reach out, we are all in this together’. It highlights the charity appearances, their photographic documentation and the totality of the site as a space to consolidate the Beyonce brand.

The management of appearance is an endless balance as Anthea Turner, a British television presenter, was to learn to her cost in August 2000 when she sold her wedding photographs to OK magazine. The story adds another dimension to the whole notion of the stolen image in commercial photography. On negotiating exclusive rights for her marriage photographs with OK magazine, Anthea claims that she was duped when asked to eat a new chocolate bar that Cadbury’s were launching. As part of the agreement with OK, Anthea had agreed to supply one picture of her wedding to the press in general. She left OK to choose the image. OK magazine chose to sell a photograph of Anthea and her husband eating the new chocolate to all the tabloid newspapers, requesting them to mention the chocolate by name in the caption. An image of Anthea in her wedding dress was also displayed on the cover of OK magazine with a free Snowflake chocolate on the left-hand side. Inside were images of Anthea, her new husband Grant and celebrity guests eating the chocolate bar. The wedding appeared to be sponsored by Cadbury’s, and with the free chocolate on the magazine cover, all readers could join in the celebrity wedding. The tabloids used the opportunity to condemn Anthea for what they do every day – exploit all opportunities for profit. They themselves obviously secured profit by condemning Anthea Turner. As Kevin O’Sullivan, the showbiz editor of the Daily Mirror, said, ‘[Anthea] certainly became the whipping girl, but you know, I think we all felt it was selling papers’ (Tabloid Tales, 3 June 2003, BBC1). The photograph in this incident was pivotal, and what was on one level an official wedding photograph turned into a stolen, almost paparazzi-style image which destroyed her celebrity status. It took her six years to develop her public status and become reestablished as a television personality. The incident indicates the multiple levels of exploitation in the field of tabloid journalism – where the exploitation of commercial profit feeds a journalism of the spectacle.

The spectacle is the stage at which the commodity has succeeded in totally colonizing social life. Commodification is not only visible, we no longer see anything else; the world we see is the world of the commodity.

(Debord 1967: Section 42)

In the glossy world of magazine culture and the proliferation of lifestyle blogs and sites on the web, there is another vast area of photography, which does not mark the existence of an event and does not constitute advertising – creative stock photography. These images fill increasingly vast digital image banks, where they can be bought and sold across the world. Generally, as David Machin writes, they can be spotted easily: they are those bright, airy images showing attractive models, flat, rich colour, and a blank background. And they are recognisably less than realistic (Machin 2004). The main reason for this is that the more multi-purpose and generic they are the more reusable they are, and therefore the more they will sell. The blank or reduced background, by de-contextualising the subject, enables the images to act as generic types. The settings that do exist are generic – a window, the sea, the mountains, an ocean or a nondescript city street. Where attributes or props do exist, they are symbolic – a computer to signify office, or a hard hat to highlight construction. The models too adhere to the mood of the generic image: ‘the models are clearly attractive, but they are not remarkable, because a striking face, an easily recognisable face, will be less easy to re-use’ (Machin 2004: 323). Machin argues that these images are changing the way in which we use and understand photography. The photograph is no longer witness here, its use is symbolic. What is interesting about these images is that they speak very little. The context provides meaning, just as the context in advertising provides meaning to those images (see ‘The grammar of the ad’, p. 253). The balance between denotation and connotation which Barthes discussed is no longer apparent (Barthes 1977b). This is a photography in which there is only connotation. As Frosh argues, the catalogues and archives act as ‘a concentrated representational space through which images are materialized: made to emerge as physically discrete and at least minimally communicative resources’ (Frosh 2003: 118).

David Machin (2004) ‘Building the World’s Visual Language: The Increasing Global Importance of Image Banks in Corporate Media’ Journal of Visual Communication 3(3).

This stock photography industry is dominated today by four firms: Getty Images, Corbis, Shuttershock and Fotolia who account for approximately $1.4 billion (50%) of the gross revenue of the industry. Corbis, established in 1989, is owned by Bill Gates and was set up because Gates believed that people would someday decorate their homes with a revolving display of digital artwork (Hafner 2007). It dominates the digital distribution of artworks from across the world. In 1994 the company shifted direction with the acquisition of significant photographic collections such as the Bettmann archive which holds some of the US’s most iconic photographs, such as that of Rosa Parks riding on a bus in 1956 or of Marilyn Monroe on a New York subway grate. The aim was to build the most comprehensive digital photographic archive in the world. Getty Images established in 1997 always described their photographic collections as creative stock as well as editorial photography (news and documentary) for commercial use, although they have also acquired significant historical collections such as the Hulton Picture Archive and those of Time and Life magazine. With Corbis holding approximately 100 million images and Getty 80 million it is clear that these companies have immense control over the visualisation of human history. The nature of stock imagery has also impacted on our own production of imagery whether on Facebook, Flickr, Photobucket or Instagram.

Geoffrey Batchen has highlighted the impact of image banks such as Corbis on our understanding of traditional photography and the role of photography in the recording of history (Batchen 2003).

Today colour supplements cannot afford to pay photographers to shoot appropriate images for all their articles, so these stock images are a cheap way of brightening up a page. Getty inform photographers of the kinds of images that they are looking for and are clearly interested in being ‘a leading force in building the world’s visual language’ as their promotional material asserts. John Morrish has highlighted how these stock images must be ‘striking, technically superb yet meaningless’ so that they will ‘never conflict with the client’s message’ (Morrish 2001). Machin argues that while these images may appear to be meaningless, in the sense that they are able to absorb radically different meanings from their context, it is not helpful to see them in this way, since what these images are doing is reasserting the concepts of branding in a non-branding context.

Let us look at an example of a mundane stock image. It depicts a woman floating in the sea in tranquillity (Figure 5.3). In searching for this image in the Getty archive, in 2003 there were 94 pages of images that depicted a woman floating in the sea connoting tranquillity or relaxation. In 2008 there were over 1,600 images in the Getty Archive depicting women floating and relaxing. In 2014 there are 2,923, many of the images are extremely similar. This image was used on a supplement to the Independent magazine for 14–20 June 2003. The image acts to highlight a feature about the best beaches in Europe. The image, however, is typical of generic images that can be used in a variety of contexts. It could just as easily have been used to illustrate an article which asked whether our seas were polluted or not or to talk about dealing with stress. This woman floats in a sea that may not even be European. In fact this same image has been used in a 2003 travel brochure by British Airways for tropical beaches. Here she visualises a section on ‘well-being’, as the copy beside the image indicates: ‘Ever imagined lazing around in your own pavilion on an isolated patch of white-sand beach, listening to the sound of waves on the turquoise sea, as the warm breeze and the touch of healing hands pass quietly by.’ She is an indistinctive model, wearing an indistinct bikini in an indistinctive sea. The photograph is striking because of the slightly peculiar angle, which emphasises her forearm and the fairly bold swathes of colour in the blue sky and what appears to be a digitally retouched green sea. The image acts perfectly to represent concepts important to the process of branding, such as con templation, enjoyment, well-being and relaxation. In fact, just in case you are in need of other similar images, when you do click on to such an image which interests you, Getty lists subjects and concepts which you may wish to explore to find similar images. The concepts are the descriptive labels, the moods that Getty perceives that the image contains. For this image they list ‘contemplation, enjoyment, getting away from it all, heat, leisure activity, relaxation, serene people, vacations and well-being’. The list of concepts to indicate various types of enjoyment and calm is detailed.

The terms and concepts around which Getty archives can be searched privilege consumer relations. If we wished to search the archive for images that comment of the class-based nature of society it is virtually impossible to make effective searches. ‘Class conflict’ brings up images of classes in war zones or of students protesting about changes in education but not ones that consider wider questions about class relations in our current age of austerity, for example. The search facilities for images are extremely important given the millions of images in Getty’s archive. Some will become practically inaccessible. This raises an important point about images, their commercial value and how profits are made.

One of the key factors which has made Getty and Corbis such profitable companies lies not simply in their ownership of images but in their ability to distribute them. Like all commodities they must circulate effectively. Getty and Corbis have corporate buyers who subscribe to their image banks, and receive feeds of new images that may be of value to them. This provides their customers with images that are relatively cheap per image but Getty makes their money through subscription, which maintains a large turnover. Their service in organising image access and the thousands of customers that turn to Getty and Corbis have meant that they pay photographers, whose labour and commodities they sell, only 20 per cent of the payout (which they have already reduced through their emphasis on increased circulation) and reap 80 per cent for themselves (Pickerell 2012). This system mirrors the increasing lack of profitability in the production of commodities world-wide where trainers cost a few pence to make through the exploitation of workers in the Global South and the profits rest in the construction of global brands where exchange value is inflated through brand identities to reap profit from unknown workers’ labour.

5.3 Stock image of a woman floating

In 2011 the stock photography industry was worth $2.88 billion (Glückler and Panitz 2013: 7). Having transformed the world’s media, however, it has now in turn been forced to re-invent itself. The increased participation of citizens across the world in photographic production has impacted on the work and profits of the large corporate image banks. At the end of 2012 there were 250 million photos uploaded to Facebook every day; 40 million daily uploads to Instagram; 10 billion photos on Photobucket from 100 million registered members; and there were 2.98 billion photos on Flickr available for public viewing (Pickerell 2013b). In 2003 and 2005 Shuttershock and Fotolia were established by young entrepreneurs as royalty-free archives that were more affordable for large and small corporations working in both print and digital media. The idea of Shuttershock enabled greater participation in the stock photo business. Anyone could upload photos without great investment and expense and create in particular those anodine, multi-purpose, generic shots of landscapes or human activity (that focuses on consumption rather than work) that are easily reusable in the world of commercial media. The rise of Shuttershock and Fotolia has not challenged photographic practice but it has undermined the profits of organisations such as Getty Images in a capitalist structure where circulation is essential for expansion and growth. In the light of these changes Getty has been forced to rethink their marketing practices as their profits on premium stock creative images began to fall from $561 million in 2012 to $300 million in 2013 (Pickerell 2013a). In 2007 Getty bought the pre-existing royalty-free stock photography company i-stockphoto to develop a midstock collection. However, while Getty had 25 million downloads from i-stock in 2010, by 2013 it was in the region of 10 million. As a result Getty images have established Thinkstock which describes itself as ‘premium art-directed and user-generated royalty-free photos, vectors and illustrations’ that are organised with budget users in mind. While a stock photograph in 2003 could command hundreds of pounds, in 2013 the figure is nearer £30 (Pickerell 2013c).

The drive to control the flow of images in both creative imagery and editorial has demanded access to images and footage of all major news events as quickly as possible and put pressure on agency staff to get access to strong images of events of global impact to maintain the reputation of the organisation as a key image source. This has at times led to unethical practices in image acqusition. In November 2013 freelance photojournalist Daniel Morel was awarded $1.22m in damages when Agence France-Press (AFP) and Getty images willfully infringed his copyright by sourcing his images from Twitter and distributing the images of the 2010 Haitian earthquake (Laurent 2013). Morel, a native of Haiti and a professional photojournalist who had previously worked for Associated Press, was in Haiti at the time and took photographs within minutes of the earthquake happening, including an image used by hundreds of newspapers and news sites worldwide of a woman being pulled from the rubble. It was first sold by AFP and Getty as belonging to Lisandro Suero. The extent of the damages awarded to Morel were because of what was described by his lawyers as the ‘lackadaisical, dismissive and inexcusably ineffective’ response by Getty and AFP to repeated requests on behalf of Mr Morel to ‘set the record straight, get the pictures down from the websites of their paying customers and stop licensing his works under their names’ (Official Transcripts 2013, Morel vs. AFP and Getty: 35).

While Getty and AFP acted in this manner, their copyright policy suggests their determination to uphold copyright infringement in the interests of both photographers and the archives and highlights their reserve right to charge five times the cost of an image that is used with copyright infringement. AFP and Getty sold 1,000 downloads of Morel’s photographs, for some of which they were paid over $1,000. While Morel was paid over $1 million in damages, the subject of the image, the woman pulled from the rubble, has no rights over its use or over the commercial value of her own image.

The tension between corporations and photographers and the imbalance of power has led to photographers trying to establish their own image banks. Stocksy is one of the most recent, which one photographer describes as a sort of ‘photographer-owned coop’ that pays photographers 50% of payouts. The tension between photographers and corporations has a long history. It led to the establishment of Magnum photography cooperative in 1947 to enable photographers to maintain control over their own photographs in a world where circulation has become more critical than production in the drive for profit (Hawk 2013).

While photographs are commodities in themselves, photography has also supported the buying and selling of every conceivable product and service, to the point where we are almost unaware of the medium of photography. Photographs for commerce appear on everything from the glossy, high-quality billboard and magazine advertisements to small, cheap flyers on estate agents’ blurbs. Between these two areas there is a breadth of usage, including the mundane images in mail-order information and catalogues, the seemingly matter-of-fact but high-quality documentary-style images of company annual reports, the varied quality of commodity packaging, and of course the photography on marketing materials such as calendars, produced by companies to enhance their status. Within the traditional histories of photography, advertising photography has largely been ignored, despite the fact that photography produced for advertising and marketing constitutes the largest quantity of photographic production. One possible reason for the lack of documentation and history-writing in this area is that commercial photog raphy, for the most part, has not sought to stretch the medium of photography, since one of the key characteristics of all commercial photography is its parasitism. Advertising photography cannot be seen to constitute any kind of photographic genre; rather, it borrows from and mimics every existing genre of photographic and cultural practice to enhance and alter the meaning of lifeless objects – commodities.

By reading the opinions of advertising photographers for the students of commercial advertising, we can explore the way in which this photography has developed the commodity spectacle. One of the first instances suggesting the power of photography for advertisers dates back to the mid-nineteenth century, when the photographer Disdéri wrote an article offering ‘indispensable advice’ to exhibitors in the 1855 Exposition Universelle in Paris, emphasising the speed, exactitude and economy of photographic reproductions and suggesting ‘wouldn’t the propagation of a model of furniture appreciated by all the visitors to the exposition attract numerous orders to the manufacturer?’ (McCauley 1994: 196). It is clear that as forms of mass production began to develop, the photograph, which constituted one of these forms, was also seen as a medium through which these commodities could be popularised and marketed. In this sense, from the very beginning photographs were employed to induce desire and promote the spectacle of commodities. Thomas Richards discusses the display of commodities at the Great Exhibition of 1851 as a spectacle of goods, a spectacle which was soon taken up by advertisers as they moved from advertising products to brands (Richards 1990).

By the inter-war period, photographs began to be used more regularly within advertisements. This was partly due to the increased production of illustrated papers during the period, but also due to the development of a visually literate British public during the 1930s, the result of the dissemination of photography through the illustrated newspaper. Two comments by those working in the industry highlight the shifting concerns for photographers during this period:

The advertisement photographer visualises his work … holding its own … where it will not be looked at deliberately unless it has the power to arrest and intrigue the casual eye of the reader.

(Stapely and Sharpe 1937)

now, the leading London dailies devote whole pages to photography, while the Sunday and Provincial press freely scatter photographs throughout their editorial columns. Photographic news brought photographic advertising and a public that had been educated to visualise the world’s events soon began to visualise its own needs.

(George Mewes of Photographic Advertising Limited 1926–60 quoted in Wilkinson 1997: 28)

It is clear that while the simple use of arresting photography was enough in the early period, as the century progressed and the regime of spectacle developed, advertising photography has sought to develop dreams and desires in the images that they create. The period of the 1930s was one of flux; while some simply interpreted the role of the advertising photographer as one who would create a striking and arresting image, George Mewes of Photographic Advertising Limited understood the role of the photographer as one who would create needs and desires. In doing this, they did not create new forms of photography, but borrowed forms of photography popularised through the new illustrated papers and through the developing film industry.

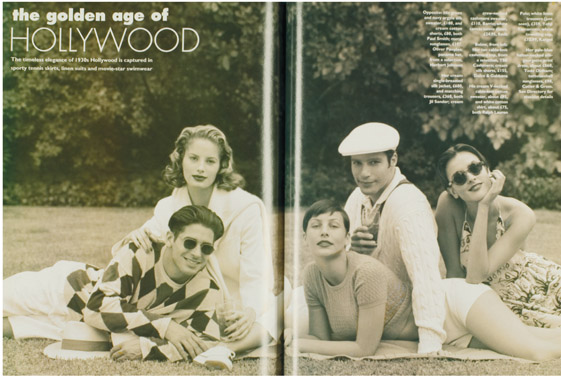

Helen Wilkinson notes how advertising photography began to appropriate, first, journalistic methods of a seemingly ‘realistic’ style as well as the conveyance of narrative through a combination of image and text; and second, commercial cinematic conventions. For example, deep shadows to convey emotions were employed along with the close-up for a more naturalistic style of portraiture, which still retained an element of glamour. Some of the cinematic conventions of photography can be seen in stock photography sheets belonging to Photographic Advertising Limited. One sheet represents head-and-shoulder portraits of women (Figure 5.4). All the women have been shot in dramatic studio lighting and wear makeup, conventions which adhere to an image of cinematic glamour. All are photographed in a relatively relaxed manner and seem to reflect moments within a narrative. Some of the women are even involved in mundane activities like eating and drinking, actions which would not have been recorded in conventional portraiture. Thus they all appear to have a degree of naturalism which could be misconstrued as ‘realism’ despite their obvious glamour. The relationship between glamour and naturalism is a key aspect of 1930s advertising photography, as Wilkinson describes in relation to a 1930s Horlicks advertisement which depicts a close-up shot of a glamorous and attractive woman in a relaxed image of Horlicks-induced sleep. The degree of naturalism allowed the ordinary consumer to identify with the model and combined with an image of glamour, provided a route to encourage desire that was transmuted to the product through the advertisement.

Glamorising mundane activities and commodities is part of the process through which photography has helped to imbue products with meanings and characteristics to which the commodity has no relationship. As Karl Marx noted, commodities are objects – usually inert – that have been imbued with all kinds of social characteristics in the marketplace. Marx called this process the fetishism of commodities, since in the marketplace (which means every place where things have been bought and sold) the social character of people’s labour was no longer apparent, and it was the products of their labour instead that interacted and were prominent. Photography is pivotal in acting to fetishise commodities in the world of advertising by investing products with what Marxists have described as false meanings (see Williams 1980; Richards 1990). Advertising photography aims to turn something which is ostensibly mundane into an exciting and arresting image. In selling dreams and aspirations commercial photography has painstakingly created elaborate yet intimate images that invite the viewer to almost imagine a story rather than just see the objects in the shot (Ward 1990).

Robert Goldman (1992) Reading Ads Socially, London: Routledge.

By the late twentieth century promotional culture had developed further to not simply suggest the ability of the com modity to fulfill aspirations but to centre the commodity as a personification of desires such as happiness and love. Robert Goldman remarked in a study of 1980s advertising imagery: ‘ads offer a unique window for observing how commodity interests conceptualise social relations’ (Goldman 1992: 2). Commodities in the late twentieth and twenty-first century are no longer inanimate objects but are invested with human qualities with which we build relationships. Perfumes, for example, literally morph into being emotions and feelings that only humans and animals can feel. They have been given names such as ‘obsession’, ‘passion’, ‘happy’, ‘freedom’, ‘dazzling’. And where they are not attributed with such emotions, narratives, tag lines and images suggest that we can have fulfilling relationships with products. Omega’s campaign with Cindy Crawford titled ‘Cindy’s choice’ presents her with a larger than life watch that, through the power of

5.4 Advertising stock sheet W1910783 from the Photographic Advertising Agency, London, 1940s

photomontage, literally encircles her protectively, replacing her husband as her partner. Photographs play a crucial role in bringing commodities alive. In another Omega advertisement Cindy looks seductively out at the viewer and the watch – enlarged to the size of a human – is photographed next to her with the tagline of ‘Omega and Cindy – time together’, constructing Cindy through text and image as in a relationship with the watch. As Joachim Giebelhausen wrote in 1963, ‘The camera has long been the favourite medium of the advertiser. It convinces with its realism even as it fascinates with the magic of a dream so that even the people of our time are cajoled into worshipping the idols it creates’ (Giebelhausen 1963). As the language of advertising has become ever more sophisticated, images have increasingly been left to speak without anchorage (Barthes 1977) and the tag line ‘Cindy’s choice’ becomes too uni-directional. The 2003 advertisement for Omega depicts a photographic image of Cindy Crawford sitting in the driving seat of an open topped car, with wind-swept hair deep in thought (The image can be viewed at: www.omegawatches.com/press/press-kit-text/364). The words ‘Cindy Crawford’ and ‘Choices’ in slightly different fonts are placed discretely over the image to the lower left divided by the photograph of a larger than life Omega Constellation watch (the only object to be enlarged in the ad) which is literally suspended between the words. Given the incompleteness of the phrase ‘Cindy Crawford … choices’ and the watch’s positioning within the phrase, the watch through its size and solidity is left to resonate as a resolution to the predicament of choices; it literally fills the gap in the phrase. The use of the photograph enables the advertisement to resonate with possibilities. The advertisement does not tell us that the watch is a solution to her choices, but we are encouraged to construct this meaning as its presence forecloses the possibility of other choices. What is visualised is a world in which commodities become central to the story of ourselves. As Jhally asserts, advertising tells us that the way to happiness and satisfaction is through the consumption of objects: ‘things … will make us happy’ (Jhally 2006: 13). While advertising traditionally placed the commodity at the centre of visual messages, such as that above, and photographs have been used to enhance the appearance of things, there are times when photographic styles of realism and documentary have been employed to challenge a world of glamour.

All photographs will be viewed by different people in different ways, whether in commercial contexts or not. The same photograph can also mean different things in different contexts, even different styles of photography will carry different messages. Let us look at an advertisement which does not use a style of photography normally associated with advertising. Because advertisers have traditionally been concerned with creating glamorous, fantasy worlds of desire for their products, they have tended to shy away from the stark, grainy, black and white imagery traditionally associated with documentary images and photojournalism. They have gone instead for glossy, high-colour photography to enhance their images of desire. Yet, at times of company crisis, or when companies have wanted to deliberately foster an image of no-nonsense frankness, they have used black and white imagery. In 1990, a short while after Nelson Mandela was released from jail by the South African authorities, the Anglo-American Corporation of South Africa brought out an advertisement entitled ‘Do we sometimes wish we had not fought to have Black trade unions recognised?’ Underneath this title was a documentary photograph of a Black South African miner, in a show of victory. At a moment when Anglo-American foresaw massive economic and political change, they attempted to distance themselves from the apartheid regime. Yet Anglo-American was by far the largest company in South Africa, ‘with a near total grip over large sectors of the apartheid economy’.3 While presenting this advertisement to the public, De Beers – Anglo’s sister company, in which they had a 35 per cent stake – also cancelled their recognition agreement with the NUM at the Premier Diamond Mines, despite 90 per cent of workers belonging to the union. The frank and honest style of address which black and white photography provided hid the reality for black workers in South Africa. The miner depicted was in fact celebrating his victory against Anglo-American in 1987. Here, at another moment of crisis, Anglo-American appropriated this image of resistance. The parasitic nature of advertising enables it to use and discard any style and content for its own ends. Anglo-American are no longer interested in fostering this image (they declined permission to have the advertisement reproduced here). There is an added irony in Anglo-American’s use of this image, since it is not strictly speaking a documentary image at all, but a montage of two images used to capture the mood of the strike as the Independent saw it.

Black and white imagery has been used in other company contexts at moments of crisis. Carol Squiers has discussed the way in which they have been used in annual reports. Black and white, she notes, ‘looks more modest and costs less to print’. As Arnold Saks, a corporate designer, said: ‘There’s an honesty about black and white, a reality…. Black and white is the only reality’ (Squiers 1992: 208). In severe cases of company crisis, even the black and white photograph could seem to be extravagant. Northern Rock’s Annual Report for 2007 following the nationalisation of the bank in order to prevent its collapse used no images.

In the world of consumer advertising, black and white documentary photography has also been used to try to encourage the idea of rational consumer choice creating a kind of factual illustrative photography, which suggests an attention to scientific detail. An advertisement for Halfords children’s bikes uses this kind of image to emphasise the inappropriateness of other manufacturers’ children’s handlebars. It is an interesting advertisement since the photograph does not actually represent their product, but a design fault in their rivals’. The advertisement also highlights the way in which the text of advertisements is crucial in anchoring their meaning. Angela Goddard and Guy Cook both discuss the way in which texts anchor meaning (Cook 1992; Goddard 1998).

Carol Squiers (1992) ‘The Corporate Year in Pictures’ in R. Bolton (ed.) The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

The symbolic value of using or not using a photograph has also been discussed by Kathy Myers in her exploration of Green advertising. At times advertisers have chosen to use and not use photographic images in an attempt to find symbols of ecological awareness (Myers 1990).

Kathy Myers (1990) ‘Selling Green’ in C. Squiers (ed.) The Critical Image: Essays on Contemporary Photography, Seattle: Bay Press.

Today photographs are primarily used to visualise concepts and situations. In marketing today branding is central. While brands have existed since the 1880s and first acted as an assurance of quality for particular commodities, as brands developed they began to create personalities, suggesting ‘lifestyles’ and with the aid of photographic imagery, fully fetishising commodities by privileging the social interactions of the market place and hiding the social characteristics of labour, as in the Omega watch ad above where we learn nothing about how the watch was made. Today, however, brands transcend beyond the material commodity to communicate not just a product but a human experience. Brands, for example, have associated themselves with emotions and qualities that belong to human beings such as inspiration, determination, fearlessness, impatience and happiness. Nike are no longer in the business of selling trainers but aim to ‘enhance people’s lives through sports and fitness’, IBM don’t sell computers but ‘solutions’ (Klein 1999). In this context photographs often act to resonate with our own experiences, triggering associations and feelings in us that latch on to memories and meanings in our own personal lives, hence the millions of ‘creative’ photographs that fill both corporate and small scale image banks constructed to symbolise concepts. In moving beyond the marketing of material goods to the marketing of ideas and feelings, in the twenty-first century brands are no longer advised to even sell to consumers but to situations (Tenno 2009).

Helge Tenno’s arguments are integrally linked to the changes taking place in methods of communication as a result of the rise of digital technologies. These changes have been hailed as groundbreaking in terms of the possibilities for consumer interaction and involvement in communication processes. Such ideas increase the centrality of viewers/consumers as creating not simply the meaning of texts but the texts themselves, shifting processes which we have seen in the production of photographic imagery. While this suggests the possibility of increased agency (groups can represent themselves), the vast accumulation of messages, visual and textual, both outside and inside digital spheres are frequently mediated through corporate communications.

How can we analyse the way these messages are structured? Do the semiotic approaches of Roland Barthes, Judith Williamson and others continue to offer ways to interrogate these texts and their role in the making and maintenance of ideologies and the hegemony of commodity culture (Barthes 1973, 1977b; Hall 1993, Williamson 1978)? The next section, ‘The grammar of the ad’, will use some of the ideas of scholars writing about advertising and mass culture to explore in detail how we may be able to read the commercial messages on new media platforms.

Roland Barthes (1973) Mythologies, London: Granada; (1977b) ‘The Rhetoric of the Image’ in S. Heath (ed.) Image, Music, Text, London: Fontana.

Stuart Hall (1993) ‘Encoding/Decoding’ in S. During (ed.) The Cultural Studies Reader, London: Routledge (first published 1980).

Judith Williamson (1978) Decoding Advertisements: Ideology and Meaning in Advertising, London: Marion Boyars.

In unravelling the meanings of images, Roland Barthes, Judith Williamson, Robert Goldman and Paul Messaris have all explored the structure of advertisements and have tried to find systems which could be applied to help decode any commercial message. In his essay ‘The Photographic Message’, Barthes described photographs as containing both a denoted and a connoted message (Barthes 1977a). By the denoted message Barthes meant the literal reality which the photograph portrayed. The connoted message is the message that makes use of social and cultural references. It is an inferred message. It is symbolic. It is a message with a code.

Paul Messaris (1996) Visual Persuasion: The Role of Images in Advertising, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Roland Barthes (1977a) ‘The Photographic Message’ in S. Heath (ed.) Image, Music, Text, London: Fontana.

In his essay ‘The Rhetoric of the Image’, Barthes explored the way advertising messages privilege symbolic and connoted meanings (Barthes 1977b). In fact Barthes argues that it is impossible to distinguish between literal and connoted messages in advertisements. If we consider the structure of signs, and the changing nature of branding where the meanings encoded encourage an identification with brands as bigger than the world of commodities, we can see these inferred messages are increasingly understood in less precise ways than is sometimes antici pated, as signs battle for attention and meaning with other signs and are constructed in the commercial world to stretch in meaning in order to accom modate an often complex global and shifting consumer base (Klein 1999). Today an advertisement rarely works independently of other media; there may be a television campaign, radio commercials, as well as other PR ‘happenings’ that all interact with each other to inflate connoted/symbolic meanings of advertising messages. In a world in which the still and moving image can be captured on cameras, phones and tablets, it also does not make sense to explore still photographic imagery in a sphere wholly separated from the moving image.

To explore the way marketing messages are constructed to transcend material goods within branded communication today and to consider the role of photographic imagery within this process, I will explore viral videos from Coke’s Open Happiness campaign.

In 2009, Coke launched their Open Happiness campaign with a music video on the television show American Idol and throughout 2009 the campaign was rolled out globally in East Asia, China, Brazil, the Middle East, New Zealand and Australia. While the initial message focused on a fantasy, psychedelic Wizard of Oz /Willy Wonka dream world of magic, surrealism and the unexpected, providing moving image compatibility with the phantasmagoria of fashion spreads by Annie Liebowitz and David La Chapelle, the campaign has expanded through installing interactive Coke dispensing machines where Coke records ‘live happiness’ in cities across the world, which are then uploaded on the internet to create ‘viral swish(es) of happiness’ (Shayon 2012). As they have sought to penetrate and develop new markets in the Global South, Coke has moved into producing 5 minute documentaries that capture the corporation granting happiness like the feudal lords of past ages. One video follows Coke’s sponsorship of Filipino migrants’ trips home to see their families, another documents Coke’s creation of a space for communication between Indians and Pakistanis. These stories have been videoed, managed and produced to create messages that Coke hopes will travel virally and touch on real human experiences that one cannot fail to be moved by. The videos provide a compelling example of what Barthes meant by advertisements failing to have denoted messages that are independent of connotation, for here despite the documentary/reality TV style narrative of workers’ dreams turned to reality, which we watch before our eyes, the real tears of joy and pain are created through and endorsed by a world of branded philanthropy. Coke employs these stories to construct itself as benign. This image of Coke as a leveller and bringer of harmony is a theme that Coke used as early as the 1970s with the song ‘I’d like to buy a world a Coke’, of which the non-commercial version ‘I’d like to teach the world to sing’ by the New Seekers became a global hit single.

The 2013 project entitled ‘Bringing India and Pakistan together’, which launched the ‘Open Happiness’ campaign in India and Pakistan, provides an example where the photographic image plays a central role in the construction of meaning in such a context. The partition of the Punjab and Bengal between India and Pakistan, led to the forced migration of 14 million people in 1947. Thousands died as a result of communal violence but amongst tales of trauma are also those of support and the memory of ancestral villages and lost friendships are still in living memory. Many families have stories of Hindu-Muslim unity which are often recalled as an innocent pre-partition world. For Punjab the fracture has never healed and the longing to build links remains amongst many, despite three wars between India and Pakistan and the intense propaganda on both sides of constructing the other nation as their enemy. The almost complete lack of communication can be seen by the level of psychological distance apparent from a question I was once asked in Amritsar by a young girl when I was about to cross the border to Pakistan. ‘What is the weather like in Lahore?’ she asked me, although the city is only 30 miles away. Coke’s project capitalises on this history of rupture and the feelings of grief and loss that still resonate today. Coke India and Coke Pakistan liased over this project which involved establishing ‘small world machines’ in Delhi and Lahore – two historic cities that both once belonged to the province of Punjab under the British Raj. The staged interactive performance was created by Coke in order to produce a 5 minute viral video for circulation, which can be viewed in full at www.coca-colacompany.com/stories/happiness-without-borders, and has received nearly 2.4 million views. There are two texts here, the performance and the viral video. The video records the interactions between residents of these two historic cities through live communication portals that look like Coke machines. Placed in shopping centres in both cities, people could see each other and communicate using powerful gestures such as touching palms, drawing peace signs or smilies, dancing, as well as, of course, drinking Coke together and waving goodbye. By following directions on screen and completing the actions, the participants are then rewarded with a free Coke that they can share together. The gesture of the open palm is also particularly significant in India, since Abhayamudra is a gesture that signifies safety and reassurance. The machines – as life-size webcams – place the camera at the centre of the experience. The machines hold an intimacy and a power that transcends the experience of Skype video because in these ‘small world machines’ we are captured through the same screen that we see the participants on the other side. The screens are not separated as they are on a computer. Indians and Pakistanis appear to inhabit spaces that are literally opposite each other. These screens are also life size – they are like the glass that separates prisoners from their families which are physically touched in ways that one imagines are similar to the prison context – the placing of palms together, or tracing movements to try at all costs to share a moment and to minimise the actual physical separation that exists. The feeling of an enforced separation is also enhanced in the video text (rather than the text of the performance), which starts with shots emphasising wire fences and barbed wire through which we see scenes of daily life from both sides with voices that speak of separation and the desire for communication that are not attributed to individuals in either country so they act to suggest the desire of both sides for the same thing. Most importantly the photographic image in these ‘small world machines’ are used in a way in which photographs have been used most powerfully – as witness and as evidence. The people on both sides witness real people on the other side participating in the sharing of moments to give evidence of the desire for change.

In Decoding Advertisements, Williamson explores the structure of the sign that contains what she describes as manifest and latent meanings in advertising messages to consider the way in which we carry out ‘advertising work’ (Williamson 1978). Our involvement in transferring meanings from one sign in an ad to another involves us in the production of ideologies that support consumerism. In these performed events, consumers do not simply work to produce meaning from advertisements but actively work to enact the events that imbue value for the commodity and are used to create the video text. In these performance and video texts we can see the way in which the commodity is no longer central. Coke here ‘markets to situations’: the longing for greater contact between India and Pakistan. People participate, accepting the staged performance of which they become the actors for the recording of an event that will witness the production of a Coke-sponsored ‘moment of happiness’. ‘A moment of happiness’ is the first textual message that we see in the video too, presented in red writing on a white background – the colours of Coke. The final message in the video text is also reserved to reaffirm Coke as a source through which we may ‘open happiness’. The quality of the photographic image as witness and evidence is crucial in impacting on the meaning-making process in both the video text and that of the performance in this example.

In his essay ‘Encoding/Decoding’, Stuart Hall considered our involvement in the production of meaning (Hall 1993). He discusses how images are first ‘encoded’ by the producer, and then ‘decoded’ by the viewer. The transfer of meaning in this process only works if there are compatible systems of signs and symbols which the encoder and decoder use within their cultural life. Our background – i.e. our gender, class, ethnic origin, sexuality, religion, etc. – all affect our interpretation of signs and symbols. Our relationship and understanding of various forms of photography are part of those signs and symbols. Hall points to the fact that messages are not always read as they were intended, because our various cultural, social and political backgrounds lead to different interpretations. Hall suggests that there are three possible readings of an image: a dominant or preferred reading, a negotiated reading, and an oppositional reading. The dominant reading would comply with the meaning intended by the producer of the image. The importance of readers interpreting images as they were intended is obviously crucial for commercial messages, and is one of the reasons why advertisers use text and montage to anchor meanings and restrict the ways in which we may interpret their images.

While Coke may endeavor to create ‘situations’ in India to develop the brand as a signifier of happiness and peace, the meaning of the brand is complicated by others that have challenged Coke’s production practices, which have caused the depletion of ground water resources to meet the needs of bottling plants in the Mehdiganj area of Utter Pradesh. Communities have held the corporation responsible for water shortages through over-extraction and pollution. Campaigns against the company have continued since 2003 and in March 2013, as Coke set up their small world machine in Delhi, community councils in Mehdiganj appealed to the authorities to reject Coca-Cola’s application for expansion and to shut down the current operations immediately to ease the water problems in the area (Figure 5.5). By April, 15 local village councils close to Mehdiganj had called upon the government to reject the corporation’s planning application. The India Resource Centre has highlighted how groundwater resources in Mehdiganj have fallen precipitously since Coca-Cola began bottling operations in the area, dropping 7.9 meters (26 feet) in the 11 years that Coca-Cola started its bottling operations (India Resource Centre 2013). The ‘open happiness’ events cloak the injustices of a corporate giant that has created devastating unhappiness in India, Columbia and many other parts of the world through production and employment practices that are solely driven by the profit motive (www.cokejustice.org; killercoke.org). Coke is set to invest $3 billion to expand its market in India through to 2020, in order to double its profits in the country through this decade (cocacola.co.uk). As corporations globalise their marketing campaign, campaigners globalise the resistance (Figure 5.6). The circulation of photographic imagery that promotes ‘situations and experiences’ remains a battleground between the hegemonic and the counter-hegemonic.

5.5 Protest at Mehdiganj to shut down Coca-Cola

Commercial photography constantly borrows ideas and images from the wider cultural domain. It is clear that when we point the camera we frame it in a thousand and one ways through our own cultural conditioning. Photographs, like other cultural products, have therefore tended to perpetuate ideas which are dominant in society. Commercial photographs, because of their profuse nature and because they have never sought to challenge the status quo within society (since they are only produced to sell products or promote commodity culture) have also aided in the construction and perpetuation of stereotypes, to the point at which they have appeared natural and eternal (see Barthes 1977b; Williamson 1978: part 2). Through commercial photography we can therefore explore hegemonic constructs of, for example, race, gender and class. Below, I consider examples from advertisements. It is just as possible to use examples from the wider gambit of commercial photography as has been highlighted above in discussing stock photography and as raised below in discussing fashion photography.

5.6 ‘The Coke Side of Labor Union’ by Julien Torres from KillerCoke.org.

Featuring Columbian Union leader Isidro Gil.

One of the key ways in which commercial photography has sought to determine particular readings of images and products has been through photomontage. Advertisements are in fact simple photomontages produced for commercial purposes, although most books on the technique seem to ignore this expansive area. While socialist photographers like John Heartfield use photo montage to make invisible social relations visible (Figure 5.6),4 advertisers have used montage to conceal those very social relations. One of the peculiar advantages of photomontage, as John Berger wrote in his essay ‘The Political Uses of Photomontage’, is the fact that ‘everything which has been cut out keeps its familiar photographic appearance. We are still looking first at things and only afterwards at symbols’ (Berger 1972b: 185). This creates a sense of naturalness about an image or message which is in fact constructed. An early example of the photomontage naturalising social relations has been discussed by Sally Stein, who considers ‘the reception of photography within the larger matrix of socially organised communication’, and looks at the rise of Taylor’s ideas of ‘scientific management’ in the factory, and the way these ideas were also applied to domestic work (Stein 1981: 42–4). She also notes how expensive it was to have photomechanical reproductions within a book in the early part of the century.

Sally Stein (1981) ‘The Composite Photographic Image and the Composition of Consumer Ideology’, Art Journal, Spring.

Yet in Mrs Christine Frederick’s 1913 tract, The New Housekeeping, there were eight pages of glossy photographic images. This must have impressed the average reader. In her chapter on the new efficiency as applied to cooking, an image was provided which affirmed this ideology as the answer to women’s work. The image consisted of a line drawing of an open card file, organised into types of dishes, and an example of a recipe card with a photograph of an elaborate lamb dish (Figure 5.7). Despite Frederick’s interest in precision, the card, which would logically be delineated by a black rectangular frame, does not match the dimensions of the file, nor does it contain practical information such as cost, number of servings, etc. which Frederick suggests in her text. As Stein points out, however, most readers must have overlooked this point when confronted with this luscious photographic image, which they would have accepted at face value.

Because the page is not clearly divided between the file in one half and the recipe card in the other but instead flows uninterruptedly between drawing below, text of recipe, and photograph of the final dish, the meticulous organisation of the file alone seems responsible for the full flowering of the dish. As a symbolic representation of modern house work, what you have in short order is a strict hierarchy, with an emblem of the family feast at its pinnacle.

(Stein 1981: 43)

5.7 Illustration from Mrs Christine Frederick’s The New Housekeeping, 1913

The more down-to-earth questions of time and money are ignored and almost banished. In response to those who believed that her reading was too contrived, Stein wrote: ‘If it seems that I am reading too much into this composite image, one need only note the title of Frederick’s subsequent publication – Meals that Cook Themselves’ (Stein 1992).

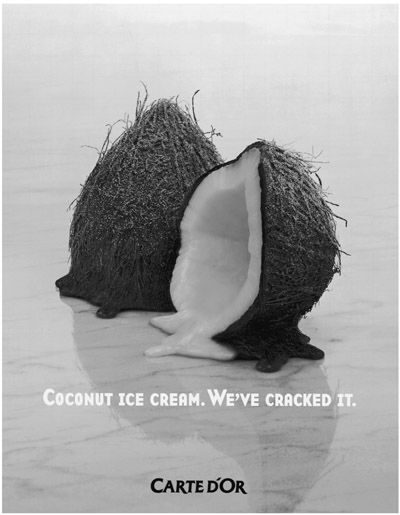

There are two key issues we can draw from Stein’s analysis. First, the example highlights the power of the photographic image to foster desire. While a rather ordinary photograph of a cake or a roast may have impressed an early twentieth-century audience, in the twenty-first century we are also seduced by the use of the latest technology and luscious photography. The photography of food continues to produce tantalising images through the play of colour and texture. Dishes are often painted or glazed to highlight colours and textures in order to produce more mouth-watering images. Roland Barthes also discussed food advertising in his essay ‘The Rhetoric of the Image’ (Barthes 1977b). Using an advertisement for Panzani pasta he highlights the sense of natural abundance that is often focused on in commercial food photography, to encourage the association of naturalness with the prepacked produce. The constant juxtaposition of uncooked fruit or vegetables with prepared food also conceals and thereby in effect dismisses the labour process. The total metamorphosis of a coconut into Carte D’Or’s coconut ice cream (Figure 5.8) is a classic example of the ability of the latest technology to deny the labour of production. The concealing of social and economic relations in advertising led Victor Burgin to create the montage ‘What does Possession mean to you?, 7% of our population own 84% of our wealth’, with a stereotypical image often found in perfume advertising of a couple embracing. Such spoof ads have become the hallmark of organisations such as Adbusters in the twenty-first century, an organisation whose challenge to the authority of corporate power encouraged the formation of Occupy Wall Street (www.adbusters.org).

Judith Williamson (1979) ‘Great History that Photographs Mislaid’ in P. Holland, J. Spence and S. Watney (eds) Photography/Politics: One, London: Comedia.

Photography and photomontage have not only acted to conceal social and labour relations, but have also acted to fetishise and romanticise the labour process. Judith Williamson has also discussed this with regard to a Lancia car advertisement from around 1978. The image depicts the Lancia Beta in an Italian vineyard. It shows a man who appears to be the owner, standing on the far side of the car with his back towards us, looking over a vineyard in which a number of peasants are working happily. In the distance, on a hill, is an old castle (this image is illustrated in Williamson 1979). Williamson asks a series of questions:

Who made this car? Has it just emerged new and gleaming from the soil, its finished form as much a product of nature as the grapes on the vine? … Who are these peasants? Have they made the car out in this most Italian field? … How can a car even exist in these feudal relations, how can such a contradiction be carried off? … What is this, if not a complete slipping over of the capitalist mode of production, as we survey a set of feudal class relations represented by the surveying gaze of possession, the look of the landlord with his back to us?

(Williamson 1979: 53)