Many experts and most laymen, Chinese and non-Chinese alike, trace China’s sustained economic growth to the expansion of rural markets and material incentives beginning in 1979. The contentions that under the People’s Commune (from here on, the commune), excessive planning and an overly egalitarian collective remuneration system reduced agricultural productivity are well accepted. Conventional wisdom suggests that market-based incentives and investments in productive capital and technology initiated during decollectivization produced a V-shaped economic recovery. Economic collapse was narrowly avoided by life-saving rural reforms, known as the Household Responsibility System (HRS, or baochan daohu in Chinese). HRS reintroduced household-based farming, which revived the rural economy after the commune’s failure.1

But was the commune an economic failure? Was the commune, as the conventional view suggests, unable to provide sufficient material incentives for rural workers, leading them to slack off or shirk their collective responsibilities? A lesser-known view suggests that the opposite is true. The commune, proponents of this alternate view maintain, helped modernize Chinese agriculture, increased its productivity, and laid the groundwork for the mass urbanization and industrialization that occurred after decollectivization.2

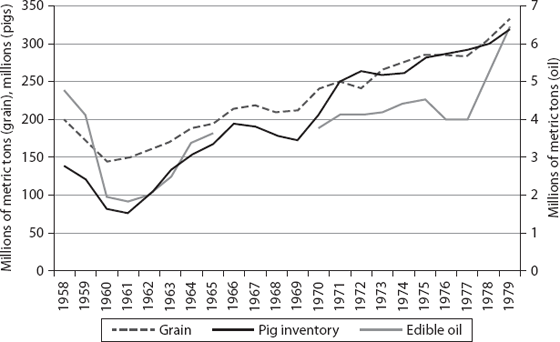

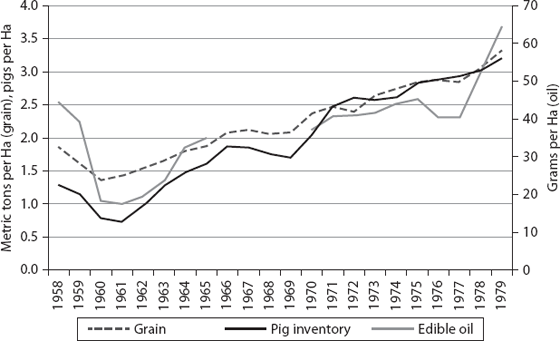

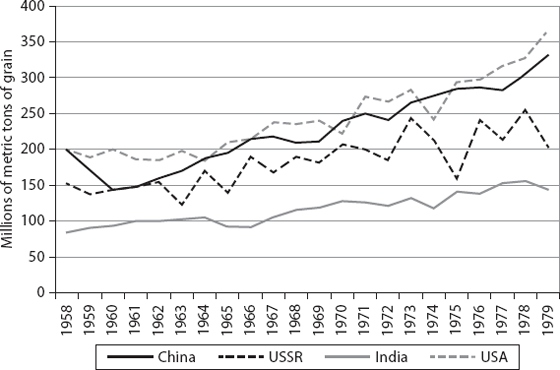

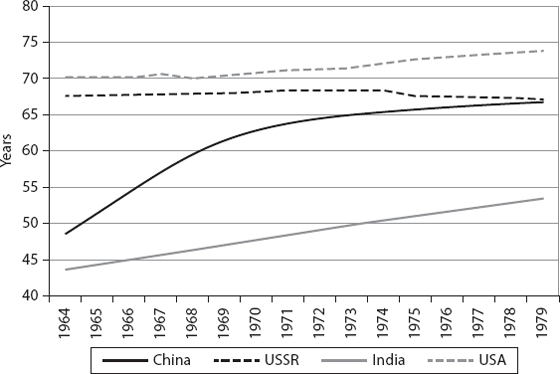

After presenting these two divergent assessments of commune economic performance, this chapter uses national-level data to evaluate which one is more accurate. Production data for grain, pigs, and edible oils, included in the “Data Presentation” section and provided along with provincial-level data in appendix A, reveal that claims that the commune failed to increase food production are largely erroneous. Considered together, these data show that after 1970, communes generated substantial increases in aggregate food production, as well as productivity per unit land and per unit labor. These trends are particularly evident in grain and pig production, which compare favorably with levels of production and life expectancy in other large agricultural countries (i.e., India, the Soviet Union, and the United States).

Simply put, the Chinese commune was not an economic failure remedied by decollectivization. During the 1970s, the commune was able to support a larger, longer-living population on a diminishing amount of arable land and to overcome high capital depreciation rates.

BOOK STRUCTURE

The chapters that follow tell the tale of the commune—why it was created, how it was transformed over the course of two decades, and how it was ultimately destroyed. They identify the three sources of commune productivity—super-optimal investment, Maoism, and organizational structure and size—and explain why and how the institution was abandoned during decollectivization.

Chapter 2 examines the origins of collective agriculture and its evolution until 1970. I argue that the commune had four distinct, yet interrelated, phases: the Great Leap Forward (GLF) Commune (1958–1961), the Rightist Commune (1962–1964), the Leftist Commune (1965–1969), and the Green Revolution Commune (1970–1979). Each of these phases was distinguished by its size, mandate, remuneration system, and strategy to promote agricultural modernization. Each also built on its predecessor, creating an institutional inertia that predisposed the commune to retain policies rarely associated with communism, including household sideline plots, cottage enterprises, and rural markets (collectively known as the Three Small Freedoms).

In chapter 3, I argue that after 1970, policies that increased household savings rates kick-started a virtuous cycle of investment that produced sustained growth in agricultural output. Using previously unexploited national- and provincial-level data, I identify three economic challenges China faced after the GLF famine—rising rates of population growth, shrinking arable land, and high capital depreciation rates—and explain the policies implemented through the commune to alleviate them. Capital investments and technological innovations made via the agricultural research and extension system increased output per unit land and labor, and freed farmers first to move into the light industrial and service sectors of the rural economy, and later to urban areas after decollectivization.

In chapter 4, I use neoclassical and classical economic growth models to identify the transitional dynamics of growth under the commune. These models clarify the patterns of productivity for each phase of the commune identified in chapters 2 and 3, and explain the relationships among relevant economic variables (i.e., technological progress, savings rates, capital investment and depreciation, and labor input) and agriculture output. This chapter demonstrates how the commune used coercive measures to increase agricultural output by underwriting super-optimal investment—that is, the extraction and investment of household resources at levels beyond what families would have saved (as opposed to consumed) had they been given the choice. The commune’s workpoint remuneration system and, to a lesser extent, redistributive policies and rural credit cooperatives helped to conceal the gradual increases in household savings rates that funded agricultural modernization.

In chapter 5, I use collective action theories to explain the importance of Maoism, the commune’s pervasive collective ideology. The commune’s collectivist ethos had five interlocking aspects: Maoism’s religiosity, the people’s militia, self-reliance, social pressure, and collective remuneration. Together, these elements constituted the institution’s essential political backbone, which allowed it to maintain higher household savings rates than members normally would have tolerated without fleeing, resisting, or resorting to slacking or shirking. Maoism helped the institution to overcome the collective action problems inherent to all rural communes—namely, brain drain, adverse selection, and moral hazard. Once extracted from households, resources were channeled into productive investments via the commune-based agricultural research and extension system described in chapter 3.

In chapter 6, I draw on organizational theories to explain how changes to the size and structure of the commune and its subunits improved its productivity. After the devastating GLF famine, the commune was substantially altered. Its size was reduced and two levels of administrative subunits were introduced: the production brigade and the production team. Exploiting two decades of detailed county-level data from Henan Province, and examining both cross-sectional and over-time variation, I find a consistent nonlinear relationship between the size of communes and their subunits and agricultural productivity. Smaller communes with smaller teams were most productive, but as commune size increased, the effect of team size was mitigated and eventually reversed such that large communes with large teams were more productive than large communes with small teams.

In chapter 7, I present a top-down political explanation for commune abandonment. This account challenges the contentions that households abandoned the commune and that it was dismantled because it was unproductive. The campaign to abandon the commune began quietly in 1977, was accelerated in 1979, and culminated in the system’s nationwide elimination by 1983. Unified by a desire to solidify its tenuous grip on power, Deng Xiaoping and his fellow reformers set out to boost rural household incomes and end Maoism. These interrelated policy goals challenged the commune’s mandate to extract household savings to underwrite investment, eliminated its collectivist ideology, and sowed discord among the institution and its subunits. Without its economic, political, and structural supports, the commune collapsed. During decollectivization, collective property and lands were distributed and the state procurement price for agricultural products was increased for the first time in nearly a decade. This distribution delivered a double consumption boost to previously deprived rural localities and won widespread political support, especially from local leaders who benefited most from the privatization of collective property.

Finally, in chapter 8, I provide a synopsis of the book and review its conclusions. I summarize the institutional changes that took place under the commune; the three sources of commune productivity examined in chapters 4, 5, and 6; and the top-down, political explanation for decollectivization offered in chapter 7.

Appendix A presents national- and provincial-level production data during the commune era for grain, pigs, and edible oil. Appendix B includes the supplemental materials for the statistical analysis conducted in chapter 6. Appendix C is a compilation of the nine essential official policy documents on the commune, most of which have not previously been translated into English. It is divided into three sections: commune creation, commune governance, and decollectivization.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW: THE PEOPLE’S COMMUNE

Beginning in 1958, for more than two decades the commune was rural China’s foremost economic and political institution and the lowest level of full-time, state-supported government.3 At their peak size in 1980, communes held about 811 million members, representing 82 percent of all Chinese, or 1 out of every 5.5 people on earth. Between 1970 and 1983, the average commune included twelve production brigades, ninety production teams, three thousand households, and about fourteen thousand people. These averages disguise substantial regional disparities in commune size, and after 1961, regardless of size, all Chinese communes shared the same three-tiered administrative structure and were coercive institutions—that is, members could not leave without permission.

The household formed a fourth subunit under the commune and controlled the rural private sector. Households supplemented their collective income with private income generated from their often home-adjacent sideline plots (ziliudi) and cottage enterprises; they would either consume these crops and handicrafts or sell them to the collective or to other households at the local market (ganji). Households had the basic facilities and supplies (i.e., a small courtyard or pen and food scraps) and the experience necessary to raise a few chickens or a pig or two. They did not compete directly with the collective, but instead worked with and received material support from their teams to ensure that any resources left over from collective production would not be wasted.4

During the Anti-Rightist Campaign, from mid-1957 until the GLF began in late 1958, between 550,000 and 800,000 educated members of Chinese society were branded as Rightists and publically denounced.5 Over the next two years, the GLF’s infamous red-over-expert policies further demoralized China’s already scarce human capital. The GLF’s failure resulted in the loss of between 15 and 30 million lives, as well as the construction of vast quantities of poor-quality physical capital and infrastructure, which either depreciated quickly or collapsed.

After the GLF calamity, in 1962, the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee officially promulgated the Regulations on the Rural People’s Communes (i.e., the Sixty Articles on Agriculture), which remained the institution’s primary working directive for two decades (see appendix C). These regulations reintroduced income incentives, private sideline plots, and free markets, and scaled back the size and mandate of communes. Public services such as collective dining and childcare were returned to household control. Throughout the 1960s, quickly depreciating rural capital stocks, population growth, and a steady decrease in arable land inhibited China’s ability to generate substantial increases in agricultural output per unit of land and per unit of labor. The effects of these severe economic challenges and China’s policy responses are detailed in chapters 2 and 3, and their transitional dynamics are elucidated using economic growth models in chapter 4.

In 1969, Premier Zhou Enlai was placed in charge of agriculture, and provincial-level meetings were held to pull together the lessons of the commune’s first decade. That year, a number of provinces—including Gansu, Inner Mongolia, Anhui, Shandong, Hunan, and Guangdong—held conferences on the topic.6 After a preparatory session in June 1970, Zhou’s agricultural policy review culminated in the Northern Districts Agricultural Conference (beifang diqu nongye huiyi, or NDAC) held at Dazhai Commune in Xiyang County, Shanxi Province, and in Beijing from August 25 to October 5. Under the slogan “Learn from Dazhai,” the conference reiterated support for the Sixty Articles and launched a nationwide rural reform agenda designed to improve commune economic performance. These reforms called for increased investment in grain production, rural capital construction, pig production, and fertilizer, and for “[investment] in agricultural machinery so that 50 percent of the land would be farmed mechanically.”7

In October 1970, China’s draft constitution reemphasized the team as the commune’s basic accounting unit (i.e., the level at which household remuneration took place) and guaranteed access to household sideline plots. In November and December, provinces including Shanxi, Yunnan, Guangxi, and Hunan held agricultural work conferences to disseminate these policies, which were published in the State Council’s NDAC report in December 1970. The following year, the CPC Central Committee transmitted to each county its directive on Distribution in the People’s Communes, which protected incentive-based remuneration and household sideline plots (see appendix C). Under the slogan “Grasp the revolution, improve production,” at least a half-dozen radical provincial leaders were replaced with proponents of agricultural policies that prioritized productivity.8

After 1970, the commune’s institutional structure and mandate remained stable for a decade. With political control, economic management, and public security unified under a single institution, virtually no dimension stood beyond its purview. Communes and their subunits administered schools, hospitals, banks, shops, police and fire departments, telephone services, post offices, and radio broadcasting; they organized local, cultural, and sports activities; and they supported propaganda-related activities. Each administrative level was charged not only with modernizing agriculture but also with building a new Maoist political consciousness based on self-reliance and patriotism and placing the collective before individual interests—a potent combination that gave cadres nearly unlimited power over the lives of commune members.

Communes implemented population control measures, such as job allocation, the household registration (hukou) system, and family planning, but above all, they were tasked with improving their subunits’ agricultural output with an emphasis on food productivity—particularly grain and pork. At each administrative level, the commune’s planting and investment plan was risk adverse and gradualist, aiming for slow and steady increases in food output, rather than intermittent surges in production followed by stagnation. Although commune leaders were under pressure to increase yields using modern capital and techniques, they enjoyed wide autonomy in choosing their approach. Commune cadres drew up preliminary production plans and budgets that apportioned quotas and agricultural inputs to their brigades. Each brigade then conducted a similar process among its subordinate teams, which, in turn, transmitted instructions to households under their jurisdiction. County, commune, and brigade leaders developed and vetted production and investment plans at an annual gathering known as the three-level meeting (sancenghui).

During the 1970s, team leaders selected the workpoint remuneration methods that best incentivized workers. Households were informed of relevant agricultural modernization plans and workpoint schemes (e.g., task rates, time rates, piece rates) during team meetings and were obliged to abide by them. During mandatory assemblies, leaders transmitted Mao’s vision of selfless collectivism via propaganda materials, songs, dances, ceremonies, and dramatic reenactments. Cadres were encouraged to take local conditions into account; were warned to avoid waste and overconsumption; and were rewarded, above all, for delivering steady, long-run increases in food grain and pig production.

WAS THE COMMUNE PRODUCTIVE?

The Conventional View: Poor Performance

This section summarizes the conventional view, which identifies the commune as an impediment to economic development and productivity—one that was unable to capitalize the rural economy, promote technical innovation, or increase agricultural output. Official accounts and many prominent researchers juxtapose the commune’s economic shortcomings with the subsequent successful introduction of markets and incentives under HRS, which, they argue, brought China’s unproductive rural economy to life. In the next section, I compare this view with a prominent alternative perspective that contends that after more than a decade of adjustments, the commune ultimately was effective in modernizing agriculture and steadily increasing food production during the 1970s.

Explanations for commune economic failure, of course, have dissimilarities. Researchers disagree with each other and the official narrative about countless details. The meaning and relative significance of policy statements, publications, and meetings are always subject to the researcher’s interpretation and explanation. Despite these variations, the essence of the metanarrative on commune failure appears consistent: the lack of incentives in Chinese communes caused collective action problems (e.g., shirking and slacking) that retarded development and reduced productivity. Members simply lacked the motivation to work hard or monitor each other’s work. As a result, a moral hazard problem developed whereby free riders neglected their collective duties, dragging down commune productivity while still reaping nearly the same rewards as actual contributors thanks to the institution’s overly egalitarian remuneration system. Over time, lackluster collective production led initially hard-working members to also begin shirking collective work and focusing on more profitable private sideline ventures.

Poor commune productivity caused rural Chinese families to go hungry, which only served to further reduce agricultural output. Sometimes rural workers would show up for collective work exhausted, sometimes they worked slowly to conserve energy, and sometimes they did not show up at all. As a result, tensions emerged between the increasingly unproductive collective and its dynamic private households. Despite a strong desire among rural residents to return to market-based household farming, explains John K. Fairbank, “highhanded but ignorant cadre intervened destructively,” stifling their pleas.9 Kenneth Lieberthal writes that the economy was entirely government administered, and “market forces and personal incentives played virtually no role in the system.” He observes:

The highest priority was developing heavy industry for defense (and prestige reasons) and maximizing urban employment, with no noticeable attention to issues of efficiency or to effective use of capital. The result was lackluster economic growth, with nearly all real gains stemming from bringing more resources to bear rather than from improvements in productivity based on technological and systems. There were no private property rights and virtually no private property at all (with the exception of peasant housing). There was almost no international trade, as Mao had pursued a policy of autarky.10

Officially, between 1966 and 1976, extreme leftist policies that “disregarded the low productivity of the countryside” unleashed “ten years of turmoil [that] caused serious damage in the rural economy.”11 A 1985 government publication described economic stagnation under the commune’s “feudal-fascist regime” and claimed that “commune members were forbidden to engage in sideline production [and] private plots were eradicated, seriously damaging normal economic life in the countryside.”12 Fairbank and Merle Goldman agree that “in the 1970s the Cultural Revolution spread its coercion into the countryside, where, for example, peasants were required to abandon all sideline occupations such as raising pigs, chickens, and ducks in order to ‘cut off the tail of capitalism.’ For many peasants this meant starvation.”13 According to Carl Riskin, “state dictated cropping plans” and “caps on team income” created a “weakening of work incentives and a palsy of creative effort,” such that “collective agriculture in many places turned passive and uninspired.”14 Kate Xiao Zhou explains economic stagnation under the commune:

Farmers … were left with little or no incentive to increase or even maintain collective productivity. Not only did the state set family autonomy aside, but it put people who were good at politics, but not necessarily at farming, in charge of farming. Cadres organized farming on a commune, brigade, and team basis, regardless of the implications for productivity. They gave farmers no individual incentives to work hard to increase the level of productivity.15

Then, according to the widely accepted official account, in 1978, eighteen brave households from Xiaogang Production Team, Yangang Brigade, Liyuan Commune in Fengyang County, Anhui, “risked their lives to sign a secret agreement to divide communally owned farmland into individual pieces called household contracts, thus inadvertently lighting the torch for China’s rural revolution.”16 Xiaogang native He Hongguang describes wretched poverty and a scarcity of agricultural capital under the commune:

By the end of 1977, the Commune members had nothing left. Nearly everyone in the village had become a beggar. The doors of 11 households were made of sorghum stalks: some were so poor that they had to borrow bowls from other families when their relatives came to visit. The village was so poor that it only had three huts, one cow, one harrow, and one plough.17

In the People’s Daily, Yan Junchang, Xiaogang’s team leader and one of the eighteen signatories, explained how a combination of hunger and Maoist politics reduced productivity and prompted villagers to abandon the collective:

Villagers tended collective fields in exchange for “workpoints” that could be redeemed for food. But we had no strength and enthusiasm to work in collective fields due to hunger. We even didn’t have time because we were always being organized by governmental work teams who taught us politics. It was then that I began to consider contracting land into individual households.18

Extrapolating from the Fengyang story, Anne Thurston explains why malnourished farmers across China continued laboring under the commune for two decades despite its poor economic performance:

One of the great mysteries of rural China during the Maoist era is why the peasants, who provided the major support for the communist revolution, did not rebel, or even fight back, when the revolution first betrayed and then began devouring them. The answer from Fengyang in famine seems obvious. Starving people do not rebel. To the extent they move at all, it is to search for food.19

According to the People’s Daily, the introduction of HRS increased Xiaogang’s food grain output from 15,000 kilograms (kg) in 1978 to 90,000 kg in 1979.20 In recognition of these extraordinary productivity increases, Xiaogang’s households received powerful public support from Anhui Party Secretary Wan Li and other top leaders, including Sichuan Party Secretary Zhao Ziyang and Propaganda Chief Hu Yaobang. According to Tony Saich, Deng Xiaoping “remained agnostic” about decollectivization until 1981.21 In his memoirs, Zhao—a principal proponent of decollectivization—describes the success of the Rural Household Land Contract (RHLC) system, also known as the HRS:

The transformation of the nationwide system of three-tiered ownership of people’s communes into the RHLC schemes was a major policy change and a profound revolution. It took less than three years to accomplish this smoothly. I believe it was the healthiest major policy shift in our nation’s history. As the implementation of the RHLC scheme expanded, starting from the grassroots and spreading upward, its superiority as a system became increasingly obvious.22 (Italics added for emphasis)

The similarity between Zhao’s account and that of Saich, who also stresses the upward spread of “grassroots” economic reforms, is notable:

In 1979 poor farmers were beginning to abandon the collective structures and grassroots experimentation took place in contracting output to the household. Gradually this practice spread throughout other areas of rural China. As late as 1981 Deng remained agnostic as to whether this was a good thing. As practice at the grass roots radicalized, the centre could do nothing but stand by and make policy pronouncements to try and catch up with reality. In this initial stage of reform it is clear that the central authorities were being led by developments at the grass roots level.23 (Italics added for emphasis)

Not all agree, however, that farmers themselves began the movement to abandon the commune. Ezra Vogel explains that when officials gave “peasants a choice between collective or household farming, they overwhelmingly chose the household.”24 In contrast to this view, Jonathan Unger claims localities were “channeled” from communes into HRS “irrespective of the types of crops grown or the level of local economic development.” According to Unger, “Contrary to repeated claims of the Chinese news media and top political leaders alike … very few villages were offered any choice.”25

Despite disagreements on the origins of HRS, there is broad agreement that it increased productivity more than the commune. According to Fei Hsiao-tung, it was only after “land was contracted to the peasant households for independent management [that the rural economy] overcame the ill effects of the commune system, which had constrained the productive forces.”26 Fairbank agrees that systemic changes that “moved responsibility down to the individual farm family provided a great incentive.” He writes:

The earlier Maoist system had used moral exhortation as an incentive, had demanded grain production only, and had banned sideline production and incipient “capitalism”—a triumph of blueprint ideology over reality. This change of system now made a big difference. Now the whole community could join in planning to maximize production and income. The result was a massive increase in both, a triumph for Deng’s reforms. This was due to new motives of personal profit.27

Again, it is noteworthy how close this narrative of commune failure remedied by HRS hews to the official position as elucidated by then-Communist Party Chairman Hu Yaobang at a speech celebrating the sixtieth anniversary of the party’s founding on July 1, 1981:

Now that liquidation of the long prevalent “Left” deviationist guiding ideology is under way, our socialist economic and cultural construction has been shifted to a course of development. With the implementation of the Party’s policies, the introduction of the system of production responsibilities and the development of a diversified economy, an excellent situation has developed in the vast rural areas in particular, a dynamic and progressive situation seldom seen since the founding of the People’s Republic.28

According to the official story and to many prominent researchers, substantial increases in rural agricultural and industrial productivity were observed only after decollectivization began in 1979. Zhou has described this process as “spontaneous, unorganized, leaderless, nonideological, and apolitical.”29 Draft animals, tools, and equipment were divided among households, which contracted the land, farmed it as they liked, and sold their crops at local free markets. The commune’s economic failure, according to the official account promulgated in 1981, prompted Chinese families to forsake it in favor of “various forms of production responsibility whereby remuneration is determined by farm output,” and “sideline occupations and diverse undertakings,” which caused “grain output in the last two years to reach an all-time high” and “improved the living standards of the people.”30 According to Huang Yasheng, by 1985, rural China became a “socialist market economy” that introduced incentives and markets, resulting in the emergence of “10 million completely and manifestly private [italics in the original]” local businesses known as town and village enterprises.31

This narrative, often referred to as Reform and Opening Up, has been the conventional interpretation in both academic and policy circles for four decades.32 In the 1980s, positive assessments of economic growth during the Mao era became politically charged—so much so that an American academic who had visited China in the 1970s risked being branded a Maoist and denied a visa.33 It was worse in China, where Deng’s emergence heralded a purge of party “ultra-leftists” whose rural policies had, according to one official account, “scorned all economic laws and denied the law of value.”34 In Henan alone, more than 1 million Maoists were detained and some four thousand were given prison sentences after closed-door trials.35 Under these conditions, few defended the austerity, self-sacrifice, and investment-first policies pursued under the commune. Instead, consumption was king and to get rich was “glorious.”36 “By the 1990s,” Chris Bramall has observed, “the academic consensus was that the Maoist commitment to rural development had been more notional than real.”37

The Alternative View: China’s Green Revolution38

Some researchers have offered a lesser-known alternative evaluation of rural economic performance during the 1970s and the commune’s legacy. They argue that the commune did modernize Chinese agriculture and increase food output and that China’s improved agricultural productivity came from the vastly expanded application and improvements in agricultural inputs and techniques. Sigrid Schmalzer observes that both modern and traditional techniques “coexisted as strategies for increasing production in Mao-era China.”39 Speaking directly to the quality of these investments and their consequences for agricultural output, John Wong observes: “There can be no doubt that over the long run such labor intensive works of the communes as land improvements, flood control and water management, have borne fruit.”40

According to Lynn T. White III, during the 1970s, agricultural advances in mechanization, seeds, and fertilizer freed up surplus rural labor and increased factor mobility.41 White explains that agricultural modernization quietly changed China’s political structure by capitalizing rural areas and increasing food production, which freed up labor; supported rural industry; and, ultimately, altered local political networks and organizational structures.42 Bramall agrees, asserting that

[t]he conventional wisdom … ignores the evidence pointing to trend acceleration in the growth of agricultural production in that decade [the 1970s] driven by the trinity of irrigation, chemical fertilizer inputs, and the growing availability of new high yielding crop varieties … Maoist attempts to expand the irrigation network were very real, and brought lasting benefits. All this continues to distinguish Maoism from the strategies adopted across most of the developing world.43

Barry Naughton also recognizes that communes “were able to push agricultural production up to qualitatively higher levels” and that “green revolution technologies were pioneered by the West, but Chinese scientists, working independently, created parallel achievements and, in one or two areas, made independent breakthroughs that surpassed what was done in the West.”44 Enhanced food security helped improve average life expectancy in China from thirty-two years in 1949 to sixty-five in 1978—compared with fifty-one in India, fifty-two in Indonesia, forty-nine in Pakistan, and forty-seven in Bangladesh.45 According to Louis Putterman:

The commune system played a major role both in the delivery of healthcare, and in the distribution of basic foodstuffs to the population, none of whom, despite their massive pressure on a meager base of land, suffered the landlessness and associated deprivation faced by tens of millions of rural dwellers in China’s otherwise similar populous Asian neighbors.46

These researchers’ contributions are vestiges of an academic literature that originated after the U.S.-China rapprochement, when Sino-American agricultural exchanges resumed for the first time since 1949. Western agricultural experts were again permitted to visit select Chinese agricultural regions—albeit under close supervision—and were allowed to observe the extensive capital investments made under the commune system. They noted reforms in China’s agricultural research and extension system, and they documented (as best as they could, using the limited data available) increases in food output, investments in agricultural capital, and technological advancements in seed varieties and agricultural chemicals.

The firsthand observations of scientists and agricultural experts from the United States and European countries as well as the data and interviews they collected provided valuable insights about Chinese agriculture in the 1970s.47 This literature contrasts with many academic works on 1970s China, which analyze either leadership politics or the sometimes-violent and disruptive urban political campaigns.48 Instead, those studying China’s agricultural sector in the 1970s and early 1980s were most interested in two closely related topics essential to evaluating commune economic performance: (1) measuring agricultural output, and (2) analyzing variations in agricultural policies and inputs and measuring their effects on agricultural output.

From August to September 1974, a plant studies delegation that included George Sprague, professor of agronomy at the University of Illinois–Urbana, spent a month visiting twenty agricultural research institutions and universities and seven communes in Jilin, Beijing, Guangdong, Shanghai, and Shaanxi. After returning, the group published a report for the National Academy of Sciences.49 Sprague summarized the report in an article in Science magazine published in May 1975:

The current ability of the Chinese people to produce enough food for over 800 million people on 11 percent of their total available land is an impressive accomplishment. This has been achieved, in large part, through the expansion and intensification of traditional practices. Water control practice—irrigation, drainage, and land leveling—now include nearly 40 percent of the cultivated area. The intensity of cropping has been greatly increased. China has probably the world’s most efficient system for the utilization of human and animal wastes and of crop residues. The development of “backyard” fertilizer plants and the utilization of hybrid corn and kaoliang (sorghum) are new elements contributing to agricultural progress.50

From August to September 1976, the National Academy of Sciences and the American Society of Agricultural Engineers (ASAE) hosted a reciprocal visit from the Chinese Society for Agricultural Mechanization (CSAM). CSAM Vice President Xiang Nan (who later became Vice Minister of Agriculture from 1979 to 1981) led the fifteen-member Chinese delegation, which visited American colleges, U.S. Department of Agriculture research stations, farm equipment manufacturers, and farms in ten states.51 In 1978, CSAM invited Merle Esmay, a professor of agricultural engineering at Michigan State University, and fourteen other ASAE delegates to visit China. From August to September 1979, these American experts traveled to Jilin, Heilongjiang, Beijing, Henan, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shanghai, and Guangdong and documented the various investments in agricultural capital and technology made under the commune.52

Bruce Stone, a researcher at the International Food Policy Research Institute, has traced the causes of changes in China’s agricultural output in the 1970s and 1980s. He has broken down China’s green revolution by inputs, first analyzing each one’s contribution to agricultural productivity and then examining their combined effects. Using this approach, Stone identifies three inputs that—when used together—were largely responsible for the rapid increases in China’s agricultural output: “improved water control, abundant supplies of fertilizers, and high-yielding seed varieties responsive to these inputs.”53 He observes that the use of any one or two of these three inputs produced some yield growth, but returns were best when they were applied together in appropriate quantities.54 Stone and Anthony Tang have found that in the 1970s China pursued an agricultural policy that was committed to the technical transformation of agriculture and included improved capital quality as “a major plank.” Despite “the paucity of hard data and the controversial nature of the political system,” they conclude that food grain output grew rapidly between 1972 and 1975—a conclusion corroborated by the data presented in figures 1.1–1.3 and appendix A.55

Between 1974 and 1978, Benedict Stavis published four essential works on the politics of China’s green revolution.56 Although his analysis spans numerous agricultural inputs, Stavis concludes that mechanization’s linkage with human capital development and income distribution gave it the greatest political and social influence.57 He explains the relationship between the CPC’s desire to develop the “worker-peasant alliance” as its political base and the commune’s mandate to modernize agricultural production. Stavis also highlights the importance of the research and extension system to provide feedback to agricultural scientists about the performance of new varieties and inputs under diverse local conditions.

Stavis’ 1978 book, The Politics of Agricultural Mechanization in China, published on the eve of decollectivization, explains the relationship between Maoist politics and China’s rural development scheme.58 He examines the commune’s institutional structure and agricultural extension system and their contribution to China’s capital and technological development.59 Stavis argues that agricultural mechanization not only increased output but also caused the expansion of localized rural industry, diversified the rural economy, and reduced rural–urban income inequality.60 He observes with foresight that, “as in Taiwan and Japan,” investments in agricultural mechanization had displaced many rural workers who were “considering migrating to urban areas in search of industrial employment.”61

Over the years, numerous other scholars have documented the wide-reaching investments in agricultural capital and technological advancements in seed varieties and agricultural chemicals made in the 1970s.62 These academic studies, which are cited throughout this volume, suggest extensive local variation in remuneration and investment strategies. Yet, they also reveal a surprising degree of consistency across time and geographic space regarding six important aspects: (1) the commune’s three-tiered administrative structure, (2) the prominence and pervasiveness of Mao’s collectivist ideology, (3) an emphasis on land (rather than labor) productivity, (4) the prioritization of grain and pork production, (5) the use of workpoints to distribute collective income, and (6) the inviolability of household private plots (ziliudi) after 1962.63

THEORY TESTING

Simply put, the conventional view asserts that the commune did not improve agricultural productivity, whereas the alternate view suggests that it did. In the conventional view, commune failure is attributed to flawed policies, which inhibited agricultural modernization and exacerbated collective action problems that “smothered the masses’ initiative for production.”64 Conversely, those who suggest the commune was productive argue precisely the opposite—that is, that institutional and policy changes contributed to agricultural modernization, thus improving agricultural productivity.

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data,” writes Sir Arthur Conan Doyle speaking as the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes: “Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”65 Indeed, the biggest weakness of the two aforementioned theories is that both lack reliable national, provincial, and county-level data that can be replicated and used to convincingly prove or disprove the validity of their claims. Claims that commune productivity was poor often are based on anecdotal accounts, personal observations, and elite interviews in the post-commune period. Despite extensive efforts to gather data, in some cases, those who argue the commune was productive also lack the appropriate data to make definitive conclusions beyond the national or a particular locality.66 This chapter and those that follow fill this gap using newly recovered national-, provincial-, and county-level data. They reveal that the commune substantially increased food output, elucidate the sources of this agricultural productivity growth, and explain why, despite its productivity, the institution was ultimately dismantled.

Case Selection

This study is based primarily on archival research and interviews with former commune members conducted in China between 2011 and 2016. These research trips uncovered a trove of heretofore-unexploited agricultural data on the national, provincial, and county levels, covering the commune era from 1958 to 1979. National productivity data are available in this chapter and data for all provinces that had communes are included in appendix A. Data on commune productivity, population growth, physical and human capital, technological innovation, and institutional structure are presented alongside other evidence, including official policy statements, the existing academic literature, and eyewitness and expert accounts. In chapters 4, 5, and 6, respectively, I interpret data with the use of economic, collective action, and organizational theories to identify causal relationships and examine the effects of capital investment and technological innovation, collectivist politics, and the commune’s organizational structure on agricultural productivity. In chapter 6, for instance, I use data from Henan’s 117 counties to conduct a statistical analysis to determine how changes in the size of the commune and its subunits affected agricultural productivity.

To explain trends across as much of China as possible, I selected provinces based on their relative population size and geographic location. I visited China’s ten most populous provinces and obtained data on agricultural inputs and commune structure from four of them: Henan, Jiangsu, Hubei, and Zhejiang.67 China is a big country, so to examine the effects of institutional change across grain types (i.e., rice, wheat, corn and sorghum), climates, and topographies, I successfully obtained data from two major northern agricultural provinces (Jilin and Liaoning) and sought data from two southern provinces (Guangdong and Jiangxi). Although my efforts in Guangdong proved to be ill fated, I fortuitously found data from Hunan at a small Shanghai bookstore.

To determine whether agricultural production improved under the commune, and to explain as much about collective agriculture as possible, I collected data on grain, pig, and edible oils production.68 These three products were controlled by the commune and its subunits, and they were the primary sources of calories for rural residents. Families often owned a pig or two. This production, however, was tied to the collective via veterinary and stud services, through loans, and in other ways that allowed it to be accounted for. Vegetables and fruits, by contrast, were generally grown on household sideline plots, making them nearly impossible to accurately quantify during the commune era.

Data Assessment

National-level data on agricultural productivity covering the entire commune era (1958–1979) are presented in figure 1.1 and are available in appendix A along with provincial-level data. Figure 1.2 reveals that the productivity of land increased during the 1970s, and figure 1.3 shows that labor productivity improved as well, albeit at a slower rate. Between 1970 and 1979, China’s production of grain, pigs, and edible oils increased by an annual average of 4.77 percent, 6.61 percent, and 6.75 percent, respectively. Within the decade, China’s grain production rose by more than 120 million metric tons, reaching 332 million metric tons total, and the country added 148 million pigs, bringing the total to 320 million pigs. Edible oil production, which was not prioritized until after 1977, showed impressive increases thereafter.69

Figures 1.4–1.6 place China in comparative perspective alongside other large agricultural countries (i.e., India, the Soviet Union, and the United States). After 1962, China’s grain production exceeded that of India and the USSR, and despite its comparatively meager base of arable land, increased apace with the United States.70 Under the commune, China’s pig production far exceeded all three of these countries, although Chinese pigs, which primarily were fed on household scraps, were about half the size of their U.S. counterparts.71 According to the World Bank, these and other improvements in agricultural productivity meant that a Chinese person born in 1970 lived an average of 14.4 years longer than someone born in 1964 (figure 1.6).

But can these data be trusted? Pre-1979 China generally is considered to be a “black box” whose statistics are either unavailable or unreliable.72 Indeed, it is prudent to be cautious and to recall that 1970s rural China had a closed economic and political system. Rural economic data were passed up from teams to brigades, to communes, to counties, to prefectures, to provincial authorities, and finally, to Beijing. Therefore, before examining the data, we must first question its accuracy.73 After an extensive examination, I have concluded that there are six reasons to believe that these data reflect genuine improvements in agricultural productivity.

First, although grain output was infamously overreported during the GLF, after the famine, grain data accuracy was greatly improved. One reason for this improvement is that the legacy of famine and excessive extraction during the GLF prompted a party-wide rebuke of official exaggeration. As part of the Socialist Education Movement begun in 1965, Jonathan Spence notes that rural cadres explicitly were ordered to “clean up” their “accounting procedures” regarding “granary supplies.”74

Second, these data include the GLF failure, which is represented by substantial declines in agricultural production at both the national and provincial levels (see appendix A). If the GLF, the commune’s catastrophe, is reported, it is reasonable to assume that these data represent officials’ best approximations regarding actual production.

Third, these data correspond with eyewitness accounts chronicled in the literature and statements by elderly former commune members who I interviewed during my fieldwork. After 1971, as noted previously, China began to allow Western agricultural experts to visit select rural areas. Although often dismissed as the fruits of a Potemkin village, the reports of foreign experts on China’s agricultural performance are corroborated by the official data and supporting evidence presented in chapter 3 and appendix A.

Fourth, it is likely that official data systematically underreported increases in agricultural output during the 1970s. To reduce their tax bills and keep more resources under their auspices, commune cadres intentionally underestimated collective productivity. The same was true of subordinate brigades and teams, which manipulated data to reflect incremental productivity increases.75 Fairbank and Goldman observe that team leaders used a “hundred ruses to deceive brigade cadres,” which included “falsifying accounts, keeping two sets of books, underreporting, padding expenses, delivering grain after dark to keep it unrecorded, holding back quantities of grain by leaving the fields ungleaned, keeping new fields hidden from the brigade inspectors.”76 Informants reveal that households also regularly underreported their private sideline production to team leaders. Bramall concludes that official agricultural data for the 1970s “systematically under-state” production levels, suggesting that the commune was more productive than the official data suggest.77

Fifth, provincial-level data reveal that productivity improvements occurred in the 1970s across a variety of geographic regions, crop types, and weather conditions. Obtaining data on agricultural inputs and production from numerous provinces across China helped mitigate the chances of systematic manipulation, poor-quality workmanship, or collusion among statistical bureaus.

The sixth and perhaps most convincing reason to believe that the commune successfully increased food production, at least apace with population growth, is that China—a closed agricultural economy that preached the virtues of “self-reliance”—added about 158 million people during the 1970s, and yet no large-scale famine was reported. This is strong evidence that the commune was able, at a minimum, to feed the rapidly growing population on less and less arable land.

Source: Agricultural Economic Statistics 1949–1983 [Nongye jingji ziliao, 1949–1983] (Beijing: Ministry of Agriculture Planning Bureau, 1983), 143, 195, 225.

Source: Agricultural Economic Statistics, 120, 143, 195, 225.

Source: Agricultural Economic Statistics, 46, 143, 195, 225.

Source: Thirty Years Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China: Agricultural Statistics of Henan Province, 1949–1979 [Jianguo sanshinian: henansheng nongye tongji ziliao, 1949–1979] (Zhengzhou: Statistical Bureau of Henan Province, 1981), 410; Agricultural Economic Statistics, 143.

Source: Thirty Years: Agricultural Statistics, 421; Agricultural Economic Statistics, 225.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2015).

After observing patterns of agricultural productivity growth during the 1970s, this study applies basic insights from economic, collective action, and organizational theories to explain these trends. Following a decade of experimentation and adjustment, beginning in 1970, gradual improvements in the commune’s organizational structure, remuneration methods, and agricultural research and extension system began a rural development process that substantially increased agricultural output over a sustained period and laid the foundation for continued productivity growth, urbanization, and industrialization after decollectivization.

The commune’s coercive extraction of household resources financed agricultural capital accumulation and technological innovation via the research and extension system. Although this system kept rural households living in austere—often subsistence-level—conditions, it bankrolled productive investments that generated the agricultural surpluses needed to kick-start a long-run cycle of sustained investment and output growth. The commune was the fundamental institutional building block of China’s investment-led rural growth strategy known as the Dazhai model.

Maoism was the commune’s collectivist ethos and political backbone. It took on religious qualities that bound members to each other and to the institution. Peer pressure, group worship, venerated texts, household registration, and shared values facilitated resource extraction from productive households and helped reduce foot-dragging and shirking. These and other aspects of Maoist ideology mitigated the collective action problems inherent to all communes, thus allowing the institution to push consumption below levels that members normally would have tolerated without resorting to slacking or shirking.

After Mao’s death, a reformist faction within the CPC leadership led by Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping destroyed the commune to solidify its grip on power. The reformers increased consumption levels to gain the political support they needed to unseat a rival pro-commune faction led by CPC Chairman Hua Guofeng. To achieve this, they destroyed the commune’s system to extract household savings to support capital investment (i.e., the workpoint remuneration system), eliminated its administrative subunits (i.e., the commune, brigade, and team), and disavowed its cohesive collectivist ideology (i.e., Maoism)—a concurrent process known as decollectivization. Had Hua and his loyalists prevailed over Deng’s reformers, however, they almost certainly would not have abandoned the commune. To the contrary, they would have used it to implement the nationwide, rural investment program detailed in Hua’s Ten-Year Plan announced in February 1978.