The process by which the people built socialism under the leadership of the Party can be divided into two historical phases—one that preceded the launch of Reform and Opening-up in 1978, and a second that followed on from that event. Although the two historical phases were very different … we should neither negate the pre-Reform and Opening-up phase in comparison with the post-Reform and Opening-up phase, nor the converse.

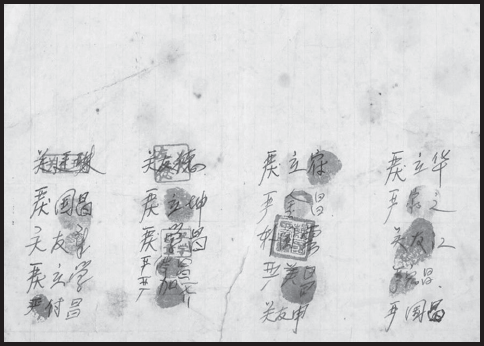

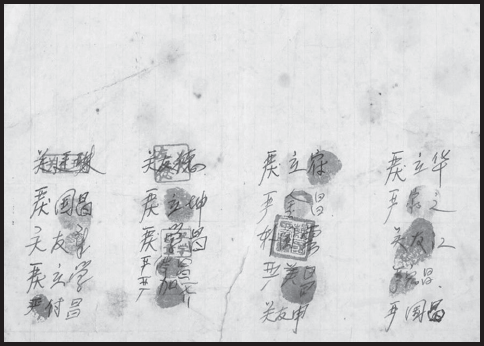

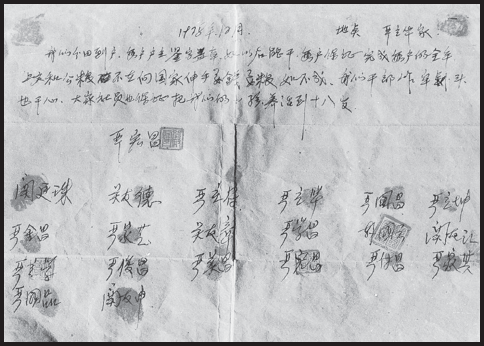

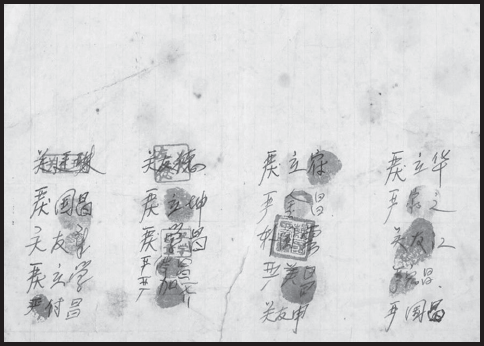

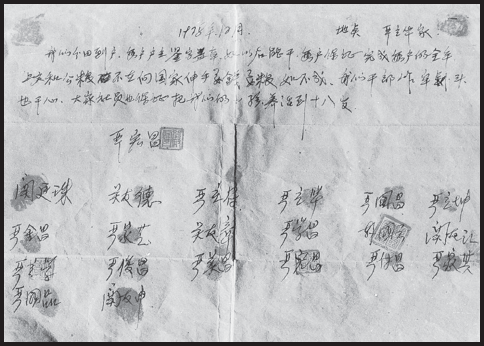

As a graduate student in 2000, I visited China to study why the country had abandoned its commune system and returned to household-based farming, a process officially known as “Reform and Opening-up” (gaige kaifang). My first stop was the National Museum of China on Tiananmen Square, to see how the institution was treated in the official history. Surprisingly, no references were made to the commune, the only trace being the tattered “secret contract” signed by the members of Xiaogang Production team in Liyuan Commune, Fengyang County, Anhui Province (figure 0.1).

According to the official account, in 1978, these courageous, starving farmers “gave birth” to China’s nationwide campaign to decollectivize agriculture. In Beijing, I also met with several Chinese experts and scholars, all of whom confirmed the official account: the commune was abandoned because it was an economic failure. Moreover, they added sheepishly, because the Chinese government does not like to admit mistakes, the institution had been largely whitewashed from the official history.

Inspired by this tale of spontaneous grassroots reform, I headed straight for Xiaogang. There, I had a chance to speak with several farmers whose names and thumbprints ostensibly appeared on the document displayed in the museum. Each of them recounted their saga of starvation under the commune and their risky gambit to increase production by abandoning the collective and returning to household farming. One old farmer, himself a signatory, reminisced about how Anhui Provincial Party Secretary Wan Li, a staunch advocate of decollectivization, had visited the county in 1977.

This comment piqued my interest and suspicions. According to the official account, the Xiaogang farmers abandoned collective farming in 1978. What role, then, could the appearance of China’s leading agricultural reformer the year before possibly have played in this ostensibly spontaneous, bottom-up process? This simple, unanswered question nagged at me for years. Then, in 2005, Xiaogang Village opened a museum commemorating its role in initiating decollectivization, which exhibited an enlarged image of the “secret contract” that sparked decollectivization (figure 0.2).2 That version, which is different from the one on display in the National Museum of China, was published online by the official People’s Daily in 2008.3 My effort to reconcile these and other inconstancies in the Fengyang story became the impetus for this seven-year study of the commune and its abandonment.

This book was inspired by the questions that emerged from my initial fieldwork in China now nearly two decades ago: How productive was the commune system? If, after the Great Leap Forward (GLF) famine (1958–1961), the commune continued to underperform, and China’s economy was closed to foreign trade, how could the country add almost 300 million people between 1962 and 1978 without experiencing another massive famine? But if the 1970s commune had been able to improve agricultural productivity, why was it abandoned? Did the farmers themselves or local team leaders decide to abandon the commune and, if so, how could a nationwide decollectivization process have unfolded in only a few years? Out of these questions, numerous others emerged: How did the commune—Maoist China’s foremost political-economic-administrative institution—work? What happened to its members? What, if any, role did it play in creating the necessary conditions for the rapid, sustained economic growth that China enjoyed in the decades after its abandonment?

To answer these and related questions, this book tells the story of the commune—one of the largest and long-lasting high-modernist institutions in human history. Its two primary conclusions are that (1) after 1970, the commune system supported an agricultural green revolution that laid the material, technological, and educational foundations for China’s emergence as an economic superpower; and (2) the system was abandoned by China’s post-Mao leaders for a distinctly political reason—that is, to vanquish their rivals and consolidate their control over China.

Over five decades, a vast literature has accumulated about the Chinese countryside during the Mao era. Journalists, novelists, and scholars have examined virtually every aspect of village life. Although they disagree on many points, a broad popular consensus has emerged in keeping with the official narrative that the commune was abandoned because it failed to increase agricultural productivity. For decades, few have hesitated to judge the institution as anything other than a mistake, a misguided social experiment that placed ideological correctness over economic realities. By the turn of the millennium, this consensus had been repeated so often that it had earned the status of a traditional interpretation. This interpretation remains the only one taught in many, if not most, Chinese and Western universities, and likely is accepted by most of the readers of this book.

What is less well known is that this traditional interpretation has long been under intensive critical review by a dozen or more agricultural economists, historians, and political scientists. Some of these researchers have used local statistical records to reveal the workings and outcomes of a particular commune or its subunits; others have combined records from several localities to explain outcomes within a particular region; still others have drawn conclusions based on national-level data, interviews, and secondary sources. Yet, the explanatory power of all three approaches has been constrained by a paucity of systematic provincial- and county-level data that has prevented scholars from offering more than strongly qualified assessments of commune economic performance and its determinants and leaving important questions unresolved.

Chris Bramall and Philip Huang, for instance, two of the most sophisticated analysts of economic development under the collective system, both focus on labor productivity but come to different conclusions. Bramall argues that, through agricultural modernization, rural collectives enhanced productivity and, thus, released labor from farming, which facilitated the development of rural industry. Huang, by contrast, stresses that because of limited arable land, communes had more labor than they could productively employ in farming, so rural industry soaked up excess workers and enhanced their productivity. But where did communes get the capital to develop rural industry? This book provides that answer: using workpoint remuneration and other secondary mechanisms, the communes suppressed consumption and extracted the meager surpluses produced by rural labor; then they pooled and invested these resources in productive capital via the agricultural research and extension system.

This study is a comprehensive historical and social science analysis of the Chinese commune—its creation, its evolution, and its abandonment. It applies well-established economic and social science theories to explain the national-, provincial-, and county-level data I collected between 2011 and 2016 (see appendix A). Although these data sources have been available for decades, they have remained scattered across dozens of provincial agricultural university libraries. On the basis of these hitherto neglected sources, this study contradicts many of the most important propositions in the traditional portrayal of the Chinese commune and its abandonment. It also sheds new light on how the institution functioned; how much food it produced; the essential role of Maoist ideology and the people’s militia; how variations in institutional size and structure affected its productivity; the role of the agricultural research and extension system; and, finally, why and how the commune was destroyed.

KEY THEMES AND CONTRIBUTIONS OF CHINA’S GREEN REVOLUTION

For some, this may be a disturbing book to read. Many of the findings presented here and in the following chapters will force the reader to confront a radically different and wide-ranging reinterpretation of China’s contemporary history and development path. The findings that emerge expose many myths that have distorted our understanding of the commune and the sources of China’s economic “miracle.” Following are eleven principal revisions to the traditional characterization of the Chinese commune:

1. Agricultural productivity, life expectancy, and basic education improved substantially under the commune. The Chinese commune evolved from an institution under which many millions starved to death in one that fed more than a billion people for two decades. According to the World Bank, the average life expectancy of a Chinese citizen increased from about forty-nine years in 1964 to about sixty-six years in 1979 (chapter 1, figure 1.6). During the 1970s, investments in agricultural capital and technology, economies of scale, diversification of the rural economy, and the intensive use of labor substantially increased agricultural productivity. The start of decollectivization coincided with historically high levels of agricultural productivity per unit land and per unit labor, life expectancy, basic literacy, and the promulgation of bookkeeping and vocational skills. Increased industrial and agricultural output under the commune can be explained using both neoclassical and classical theories of economic growth (see chapter 4).

2. The decision to decollectivize was overwhelmingly political, and it was made by China’s top leaders, not rural residents. In December 1978, Party Chairman Hua Guofeng’s “loyalist” faction lost a bitter political battle to control China to Vice-Chairman Deng Xiaoping’s rival “reform” faction. The commune’s fate figured prominently in this power struggle: Hua’s supporters were pro-commune, whereas Deng’s supporters promoted decollectivization. Hua had advocated continuing China’s commune-led economic development strategy, known as the Dazhai model. In February 1978, when Hua announced his Ten-Year Plan calling for “consolidating and developing the people’s communes,” nobody predicted that within five years the institution would be gone.4 Throughout 1977 and 1978, Deng and his provincial allies (including Zhao Ziyang in Sichuan and Wan Li, the Anhui party secretary who visited Xiaogang) worked to build local support for the Household Responsibility System (baochandaohu) and end Maoist indoctrination. These policies intentionally undermined the communes’ ability to extract from households and eroded the Maoist ideology that bound commune members to each other and the institution. Collective property and lands were distributed to households, and localities’ capacity to extract households’ resources was reduced substantially. The state procurement price for agricultural products was increased for the first time in nearly a decade. By redistributing valuable capital and land, and by paying farmers more for their crops, decollectivization delivered a double consumption boost to previously deprived rural localities and won widespread political support, especially from local leaders who benefited most from the privatization of collective property. Chinese reformers, in short, eliminated the commune to consolidate their power and not because the system failed to increase agricultural productivity.

3. The commune was not an “irrational” system created and perpetuated by brainwashed Maoists who failed to consider, or were indifferent to, economic outcomes. The opposite was true; that is, the primary objective of the commune’s creators (including Mao Zedong) was to increase rural development to improve agricultural productivity with a focus on grain and pig production. The Maoists obsession with long-run increases in agricultural production meant that they subordinated household consumption in favor of extracting more resources to invest to increase productivity. But, although an increasing percentage of household savings was extracted, after the GLF, there is no evidence that commune members were starving or too hungry to work. The workpoint remuneration system was designed to incentivize rural residents to work hard and maintain consumption levels that were just high enough to enable them to do so. Rather than starve people, which would have reduced their productivity, the objective was to extract the maximum percentage of annual household income to support continuous investments in capital and technology to increase food production.

4. Before China’s green revolution, communes had both a surplus and a scarcity of labor. During planting and harvest, communes often faced labor shortages, whereas during the slack season, there was generally a sizable surplus of labor. In practice, this meant that although farmers often had free time, they were still tied to the land during certain times of the year when they worked round the clock and sometimes even slept in the fields. During the slack season, farmers were encouraged to create cottage industries and sideline plots to meet latent market demand for basic consumer goods and vegetables, but they would be punished for working them instead of the collective fields during planting and harvesting time. Simply put, commune and brigade enterprises and factories gave farmers something to do when they didn’t have fieldwork, thus making them more productive and expanding their skills beyond agriculture alone. By the mid- to late 1970s, sustained investments in agricultural modernization and population growth had left millions of farmers with little to do and less and less land to do it on. Yet they remained trapped in the countryside until decollectivization when the end of collective remuneration rendered the residency permit (hukou) system unenforceable. Beginning in the early mid-1980s, tens of millions of farmers began moving to urban areas—an internal migration that has continued for more than four decades. The first generation of these migrants—who acquired their basic reading, bookkeeping, and vocational skills in communes—improved the efficiency of urban industries and became a sizable contingent of the skilled workforce that fueled economic growth in the 1980s and 1990s.

5. Private household plots, small-scale animal husbandry and cottage industries, and rural markets (collectively known as the Three Small Freedoms) were formally adopted in 1962 and practiced throughout the remainder of the commune era—including during the Cultural Revolution. These activities were legal and conducted openly under the auspices of commune, brigade, and team cadres. They provided an essential consumption floor for households and were often its primary source of vegetables, eggs, meat, and cash income. Commune subunits were encouraged to support households’ investments through small grants and loans, improved seed varieties, fertilizer, machines, and veterinary and stud services. Rural markets provided an outlet for excess private household production, created income for the elderly, and offered the pricing information cadres needed to make productive investments.

6. The commune system was not collapsing economically when decollectivization began. This study uncovered no evidence that economic or grassroots pressures alone would have been sufficient to bring down the commune system without direct intervention from political leaders in Beijing and provincial capitals. The system was all any rural Chinese under the age of twenty-five had ever known, and they presumed it would remain in perpetuity. No scholarly or official publications before 1979 have been uncovered that predicted China would soon decollectivize. Many former commune members interviewed for this project claimed they were also surprised, both by the decision to decollectivize and by how quickly it was implemented.

7. Able-bodied farmers rarely slacked or shirked collective labor. Rather, communes incentivized farmers to overwork, and then underpaid them. Workpoints, regardless of how they were awarded, were the institution’s primary method of remuneration and resource extraction. After the Northern Districts Agricultural Conference in 1970, a variety of workpoint remuneration methodologies—such as task rates, time rates, and piece rates—became permissible and generally were decided at the team level. The value of the workpoint was determined by each team after the harvest and all taxes and production and social service costs had been deducted. Regardless of how many workpoints were awarded to members or which method was used to disburse them, about half of gross collective income was extracted before members were allowed to squabble over the remainder. Because members did not know how much their points would be worth as they were earning them, they strove to accumulate as many as possible, which disincentivized slacking and shirking and allowed the collective to minimize household consumption and maximize investment. In some localities, team leaders awarded or deducted workpoints based on a member’s performance; in others, the contribution of more productive workers, as well as the harm done by loafers and free riders, was broadcast each day at team meetings or over the village loudspeakers.

8. Red China’s green revolution was made possible by reforms to the nationwide agricultural research and extension system undertaken during the Cultural Revolution. China’s substantially increased food production was the result of the vastly expanded application of improved agricultural inputs (e.g., hybrid seed varieties, fertilizers, mechanization, and irrigation) that, when used together, were extremely effective. The reformed agricultural research and extension system rewarded applied, results-driven science over theoretical work. It was a vertically integrated subinstitution nested into the commune and its subunits that responded to local needs and developed crops appropriate for local conditions. Experts were rotated on a three-year basis: the first year in the lab, the second in a particular commune, and the third traveling around a particular prefecture or province to test innovations and farming techniques on a larger scale. Despite its extraordinary success, when the commune was destroyed, so was its agricultural research and extension system.5

9. The commune was the church of Mao. Maoism was an essential psychological tool that cadres used to coerce households to forgo a larger portion of their income than they otherwise might have done without resorting to foot-dragging or outright protest. After the GLF, Maoism became a national religion that demanded total loyalty to the chairman and to the collective and was fanatical about increasing agricultural production. During decollectivization, China’s new leaders destroyed Maoism, and with it the bonds that had united commune members to each other and the institution. Stripped of their “god” and faith, collective action problems (i.e., brain drain, adverse selection, and moral hazard) quickly spread among commune members and tore the institution apart.

10. The people’s militia was an important conduit to transmit Maoism into every rural locality, and an institutional connection between Mao and the military. The people’s militia, a semiautonomous substitution nested within the commune and its subunit the brigade, linked Maoism with the prestigious People’s Liberation Army. Despite its purported tactical value to the military, Mao’s reasons for establishing the militia were primarily political: to create an informational conduit accountable to him alone, through which Maoism was transmitted to the commune and local reports were transmitted back up to Mao via the military—rather than the party—bureaucracy. Militia units became an integral component and proponent of Mao’s collectivist ideology under the commune and were linked by state media to the Dazhai agricultural model. Like the “guardians” in Plato’s Republic, the militiamen’s ideological commitment placed them in the distinguished position of enforcing both the commune’s collectivist ethos and its external security. They conducted regular political propaganda and study sessions using the Little Red Book and other approved texts and often were called on to set the pace during collective work. When the commune was abandoned, the militias, whose members were paid in workpoints, were disbanded.

11. Taken together, the relative size of the commune and its subunits were statistically significant determinants of its agricultural productivity. The commune’s structure was substantially altered after the devastating GLF famine to increase agricultural productivity. These reforms reduced its size and introduced two levels of administrative subunits—the production brigade and its subordinate production team. In the decade after its creation, the size of the commune and these subunits were adjusted continuously. The empirical analysis of data covering all 117 counties in Henan Province presented in chapter 6 reveals that taken together these changes in the relative size of the commune and its subunits were a statistically significant determinant of the temporal and geographic variations observed in agricultural output. Commune relative size exhibits a strong influence on the effect of team size, such that when average commune relative size is small, smaller teams have higher agricultural output; however, as average commune size increases, the effect is mitigated and even reversed. Large communes enhanced public goods provision, which increased the marginal productivity of labor and reduced the importance of close monitoring of workers. Hence, the advantage of smaller teams becomes less obvious and having fewer, larger teams can simplify agricultural planning and the allocation of productive factors. In this way, increased organizational efficiency at the supervisory level helped mitigate the negative effects of the free rider problem at the working level. Simply put, the increased efficiency gains from economies of scale in larger communes mitigated the negative effects of reduced supervision in larger teams.

Even this summary of revisions to the traditional characterization of the commune and its abandonment raises the question of how those who dismissed the institution as an economic failure and accepted the story of spontaneous grassroots decollectivization could have been so wrong. The scholars whose views are now called into question were conscientious and diligent; they strove to portray Chinese history as it actually was. The explanation, then, does not turn on issues of personal bias. Rather, it hinges to a large extent on the lack of available data about the commune, and the success of the four-decades-long official campaign to downplay its productivity to justify its abolition on economic rather than political grounds. Times have changed, however; the requisite data are now available to allow researchers to shed light on how the commune worked and its contribution to the country’s modernization.

This study makes intuitive observations using simple data about productive inputs (e.g., fertilizer, tractors, seed varieties, and vocational training) and agricultural outputs (i.e., grain, pigs, and edible oils). Although less captivating than firsthand accounts, these records are vital to explaining and judging the commune’s performance and to understanding how it worked and why it was abandoned.

In considering the evidence presented in this book, readers should remember the limitations of the data and theories presented, which answer an important but narrow set of questions. Data on the amount of fertilizer, the number of tractors, or the size of commune subunits in a particular province, for instance, cannot directly measure the quality of people’s lives or their relations with their neighbors. Nor is it possible to develop a meaningful index of the effects of commune life on the personality or psychology of those who lived under the institution. This does not mean these critical aspects have gone entirely ignored; much important information was gleaned from numerous discussions with Chinese agricultural experts and former commune members, as well as from press articles and scholarly works. However, detailed provincial- and county-level data on capital investment, food productivity, and institutional size and structure have long been required to place these supporting materials in their proper context. Without systematic time-series data to serve as a ballast, accounts of commune performance have tended to vary widely based on the perspective and experiences of the author or those interviewed as well as on the locality or region under examination.

Another word of caution is in order. There is no such thing as errorless data. All researchers must grapple with the nature of the errors contained in different types of data, and the biases that such errors may produce in conclusions that are based upon them. Evidence does not fall neatly into two categories—good and bad—but along a complex continuum in which there are many categories and varying degrees of reliability. This study’s conclusions are based primarily on evidence from the most reliable end of the continuum: systematic data. Even when biased, systematic data were prioritized over fragmentary data, because the nature of the bias could be elucidated. The least confidence was placed in fragmentary evidence based on the unverifiable impressions of individuals whose primary aim was the defense of an ideological position. Eyewitness accounts were considered more reliable, but they exist in only a somewhat-random pattern, especially in a country as large and diverse as China. Regardless of how often they have been repeated or the objectivity of the sources, arguments based only on impressionistic, fragmentary evidence were considered less reliable than those based on systematic data. This study used fragmentary, impressionistic, and eyewitness evidence in two ways: (1) to illustrate conclusions based on systematic data, and (2) to fill gaps in areas in which it is not possible to gather systematic data, such as workpoint remuneration methods or the practices of Maoist “worship” ceremonies.

Finally, whenever possible, this book avoids the word “peasant.” This decision was intentional, as the term has become a contentious catchall, an often-pejorative moniker for small rural landholders. Paul Robbins defines “peasants” as “households that make their living from the land, partly integrated into broader-scale markets and partly rooted in subsistence production, with no wage workers, dependent on family and extended kin for farm labor.”6 Such definitions, as the reader will soon discover, are an ill-fitting description of life under the commune, and thus the more accurate terms “team members,” “rural residents,” and “farmers” are used instead. Commune members were neither slaves nor landless “peasants”; they were members of an institution that was supposed to and, in the most basic sense did, guarantee their livelihood and take their interests into account.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are nine people without whom this book would not have been possible: Richard Baum, Ronald Rogowski, Marc Blecher, Theodore Hutors, Herman Pirchner, Wang Duanyong, Anne Thurston, Yang Feng, and my wife, Iris. Professor Baum was both a mentor and exemplar. For six years (from 2006 to 2012) under his exceptional tutelage, I studied how to interpret the machinations of the Chinese policymaking process and conduct field research in China. Ron provided essential theoretical and historical insights and introduced me to the economic theories of W. Arthur Lewis, which unlocked the relationship among the causal variables. Marc’s meticulous feedback on my chapters, continuous intellectual and moral support, and limitless knowledge of the political economy of rural China were indispensable. Ted was instrumental, not only in teaching me the Chinese language, but also in encouraging me to continue my research despite some initial setbacks. Herman supplied the guidance and support I needed to keep mind and body together throughout the lengthy research and writing process. Duanyong deserves special thanks for his unparalleled efforts, thoughtful critiques, generous dedication of time, and insights into rural development in Henan. Professor Thurston’s course on grassroots China at Johns Hopkins SAIS, particularly our class trip to meet the members of Xiaogang Production team in Liyuan Commune, Fengyang County, Anhui, proved the inspiration behind this project. I am grateful to Yang Feng for helping make the statistical model in chapter 6 a reality. Most important, day in and day out, Iris’ support and encouragement were the emotional bedrock that sustained me.

Several other people deserve special recognition. My mother-in-law Sun Guihua’s first-hand accounts of life in Weihai, Shandong, in the 1960s and 1970s opened my eyes to the hardships of austerity under the commune. Lynn T. White III provided me with essential mentorship and expert comments on my chapters and I am most grateful for his excellent foreword. Richard Lowery offered critical advice and suggestions to ensure that I correctly applied and specified the Solow–Swan economic model, while Thomas Palley lent essential support on the classical framework. Eric Schwartz skillfully shepherded the manuscript through the publication process at Columbia University Press. I am grateful to both anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and support for the book. I would also like to express my gratitude to the numerous Chinese academics and former commune members that shared their insights and hospitality with me during my fieldwork. I am grateful to the dozens of librarians and graduate students at China’s agricultural universities who helped me navigate their institutions and archives.

Through countless correspondences, professors Edward McCord, Li Huaiyin, Dorothy Solinger, David Zweig, Harry Harding, Michael O. Moore, Jonathan Unger, Edward Friedman, Frederick Teiwes, Pricilla Roberts, Arne Westad, and Andrew Field were generous with their sharing of insights and research. Professors Arthur Stein, Barbara Geddes, Michael Ross, and Michael O. Moore always made time to provide their sound advice and strategies for field research and writing. Zachary Reddick contributed his excellent research and insights on China’s military. Peggy Printz shared her recollections and unique pictures of Guang Li Commune in 1973. Tang Ying shared her images and recollections of rural Fujian in the 1970s. Liz Wood and Ilan Berman supplied expert editorial assistance. Li Xialin inputted the data. James Blake and Roche George helped edit the images. Gu Manhan, Luo Siyu, and Mi Siyi provided essential research and produced the high-quality graphic displays in book. I am grateful for the ongoing support and encouragement of longtime friends and mentors Jonathan Monten, Randy Schriver, Devin Stewart, Richard Harrison, Jeff M. Smith, William Inboden, Rana Inboden, Jamie Galbraith, Jeremi Suri, Catherine Weaver, David Eaton, Josh Busby, Joseph Brown, Jack Marr, and Sifu Aaron Vyvial.

I would also like to recognize several institutions for their financial support for my fieldwork in China: the University of Texas at Austin, LBJ School of Public Affairs; the American Foreign Policy Council; the Clements Center for National Security; the Strauss Center for International Security and Law; the UCLA Political Science Department; the UCLA Center for International Business Education and Research; New York University–Shanghai; and the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs.

Finally, this book stands on the shoulders of two groups of people I will never meet. The tens of thousands of men and women who diligently recorded, collected, and published the data presented; and the economic theorists W. Arthur Lewis, Robert Solow, and Trevor Swan, whose models I used to explain it.

Austin, Texas

January 1, 2018